Path toward a Child-Centered Approach in the Czech Social and Legal Protection of Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Child Protection Approaches

2.2. Social and Legal Protection of Children in CZE

- (a)

- The fundamental right of the child—the best interest is assessed and taken in to account.

- (b)

- Interpretation principle—if it is possible to interpret a legal regulation in multiple ways, the one that most effectively fulfils the best interests of the child shall be chosen.

- (c)

- Procedural rule—whenever a decision is made that could affect the child, it is necessary to assess what positive or negative effects the decision may have on the child.

2.3. Background for Implementation of the Analysis

3. Methods

- RQ1:

- How is a child’s role understood and described in professional texts in the area of social and legal protection of children?

- RQ2:

- How are reasons for social and legal protection of children understood in the texts?

- RQ3:

- How is the objective of social and legal protection of children understood in the texts?

- RQ4:

- How is the process of assessment and intervention in the area of social and legal protection of children understood and described in the texts?

4. Results of Thematic Analysis

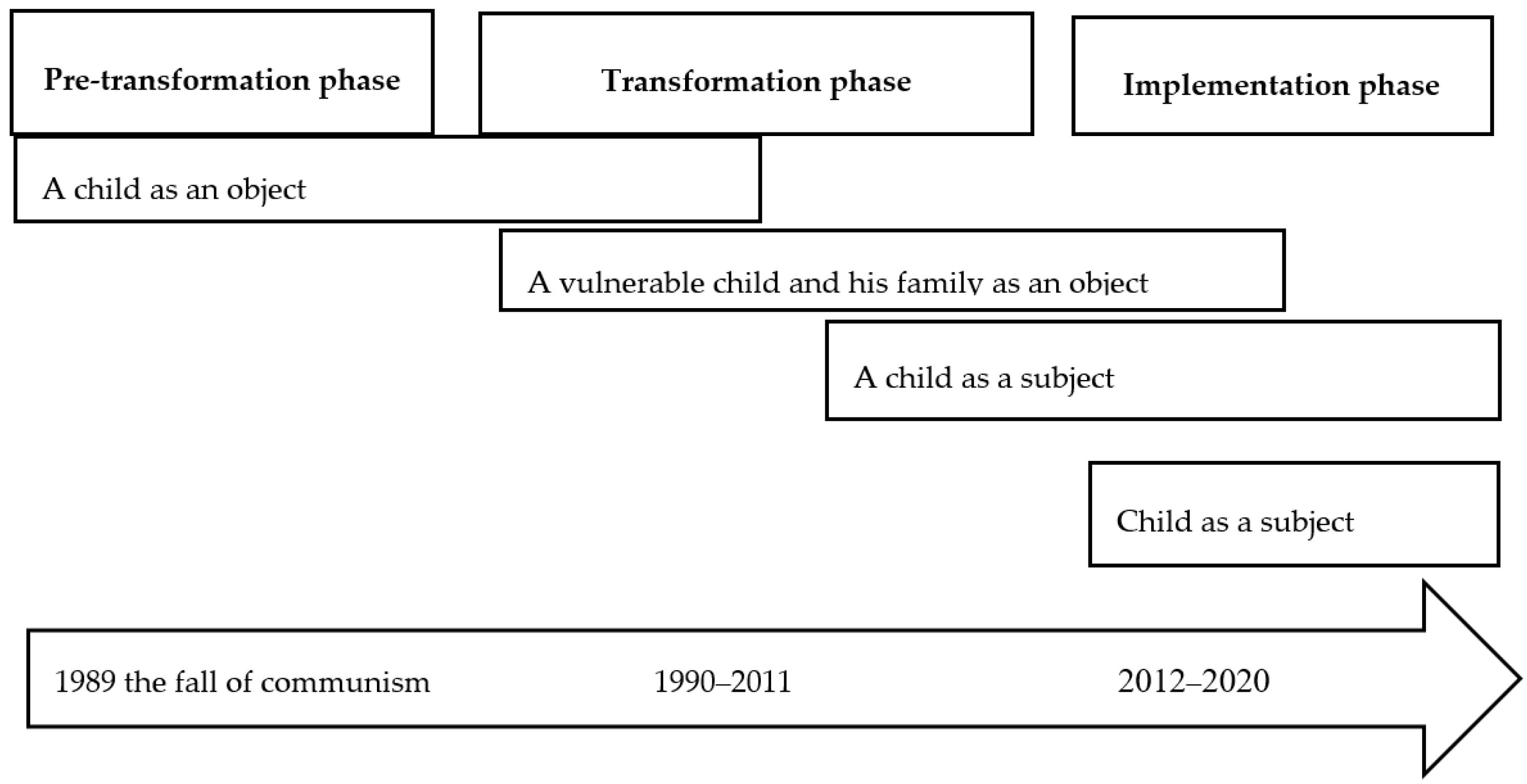

4.1. A Child as an Object of Protection from a Dysfunctional Family

4.2. A Child at Risk and the Family as an Object of Protection Against Disadvantage

4.3. A Child and Child’s Family as a Subject

4.4. A Child as a Subject of Protection

5. Discussion

5.1. Identified Child Protection Models and Their Development over Time

5.2. Barriers to Orientation to the Child’s Needs and Perception of a Child as a Subject

5.2.1. System Fragmentation

5.2.2. Weaknesses in the Training of Social Workers

5.2.3. Absence of Information-Based and Evidence-Based Practice

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nosál, I. Participace dětí na vlastním osudu–spolupracující a na řešení zaměřené způsoby práce s dětmi v náhradní péči. In Participace a nové přístupy k práci s ohroženými dětmi a rodinami; Nosál, I., Čechová, I., Eds.; Česko-Britská o.p.s.: Brno, Czech Republic, 2014; pp. 14–37. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, N. Challenges to practice and knowledge in child welfare social work: From the “social” to the “informational”? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2009, 31, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, T. The influence of child protection orientation on child welfare practice. Br. J. Soc. Work 2001, 31, 933–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, R. Adversity, resilience, and young people: The protective value of positive school and spare time experiences. Child. Soc. 2000, 14, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R. Supporting Families: Child Protection in the Community; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, O. Neglected Children and Their Families; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Roose, R.; Roets, G.; Schiettecat, T. Implementing a strengths perspective in child welfare and protection: A challenge not to be taken lightly. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2012, 17, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, C.; McGregor, C.; Cassidy, A. Early implementation of a family-centred practice model in child welfare: Findings from an Irish case study. Practice 2017, 29, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pösö, T. Combatting child abuse in Finland: From Family to Child-Centered Orientation. In Child Protection Systems: International Trends and Orientations; Gilbert, N., Parton, N., Skivenes, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 112–130. [Google Scholar]

- D´Cruz, H.; Stagnitti, K. Reconstructing child welfare through participatory and child-centered professional practice: A conceptual approach. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2008, 13, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Toros, K.; Tiko, A.; Saia, K. Child-centered approaches in the context of the assessment of children in need: Reflections of child protection workers in Estonia. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkerton, J.; Dolan, P. Family support, social capital, resilience and adolescent coping. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2007, 12, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivenes, M. Norway: Toward a Child-Centric Perspective. In Child Protection Systems: International Trends and Orientations; Gilbert, N., Parton, N., Skivenes, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 154–180. [Google Scholar]

- Spratt, T.; Nett, J.; Bromfield, L.; Hietamäki, J.; Kindler, H.; Ponnert, L. Child protection in Europe: Development of an international cross-comparison model to inform national policies and practices. Br. J. Soc. Work 2015, 45, 1508–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, E. Trafficked children and child protection systems in the European Union. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2019, 22, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, M. The Administrative and Practice Context: Perspectives from the Front Line. In Rethinking Child Welfare in Canada; Wharf, B., Ed.; McClelland and Stewart: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, N. Safeguarding Childhood: Early Intervention and Surveillance in a Late Modern Society; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, E. The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report, a Child-Centred System; The Stationery Office: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Prilleltensky, I.; Prilleltensky, O. Towards a critical health psychology practice. J. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerson, J. Hope Springs Maternal: Homeless Mothers Talk About Making Sense of Adversity; Gordian Knot Books: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Swick, K.J.; Williams, R. The voices of single parent mothers who are homeless: Implications for early childhood professionals. Early Child. Educ. J. 2010, 38, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skott, B.P. Motherhood Mystique. In Encyclopedia of Family Studies; Shehan, C.L., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Warshak, R.A. Custody Revolution: Father Custody and the Motherhood Mystique; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sinai-Glazer, H.; Peled, E. The perceptions of motherhood among family social workers in social services departments in Israel. Br. J. Soc. Work 2017, 47, 1482–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, K. Manufacturing ‘Bad Mothers’: A Critical Perspective on Child Neglect, 2nd ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, H. Social work, individualization and life politics. Br. J. Soc. Work 2001, 31, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scourfield, J. Constructing men in child protection work. Men Masc. 2001, 4, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewart-Boyle, S.; Manktelow, R.; McColgan, M. Social work and the shadow father: Lessons for engaging fathers in Northern Ireland. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2015, 20, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D´Cruz, H. Constructing the identities of ´responsible mothers, invisible men´in child protection practice. Sociol. Res. Online 2002, 78, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, B.; Gupta, A.; Morris, K.; Warner, J. Let’s stop feeding the risk monster: Towards a social model of ‘child protection’. Fam. Relatsh. Soc. 2018, 7, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, H.; Carr, N.; Whelan, S. ‘Like walking on eggshells’: Service user views and expectations of the child protection system. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2011, 16, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.; Kelly, L.; Leslie, B. Parental participation in statutory child protection intervention in Scotland. Br. J. Soc. Work 2016, 47, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, H. Constructing Meanings and Identities in Child Protection Practice; Tertiary Press: Croydon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, N.; O’Byrne, P. Constructive Social Work: Towards a New Practice; Macmillan: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ruch, G. Relationship-based practice and reflective practice: Holistic approaches to contemporary child care social work. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2005, 10, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.; Lewis, V.; Ding, S.; Kellett, M.; Robinson, C. Doing Research with Children and Young People; Sage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Welbourne, P.; Dixon, J. Child protection and welfare: Cultures, policies, and practices. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2016, 17, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pösö, T.; Skivenes, M.; Hestbæk, A. Child protection systems within the Danish, Finish and Norwegian welfare states–time for a child centric approach? Eur. J. Soc. Work 2014, 17, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Race, T.; O’Keefe, R. Child-Centered Practice; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bijleveld, G.G.; Dedding, C.W.M.; Bunders-Aelen, J.F.F. Chidren’s and young people’s participation within child welfare and child protection services: A state-of-the art review. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2013, 20, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seim, S.; Slettebø, T. Challenges of participation in child welfare. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2017, 20, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špiláčková, M. Soziale Arbeit im Sozialismus: Ein Beispiel aus der Tschechoslowakei (1968–1989); Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; pp. 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Radvanová, S. Ubližování dětem-nebezpečná rodina. In Pocta Otovi Novotnému k 80. Narozeninám, 1st ed.; Vanduchová, M., Gřivna, T., Eds.; ASPI: Praha, Česká Republika, 2008; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin, R.; Newell, P. Implementation Handbook for the Convention on the Rights of the Child; UNICEF: Geneva, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 102–460. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M. The Best Interests of the Child. In A Commentary on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child; Alen, A., Lanotte, J.V., Eds.; Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2007; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- The Supreme Court of the Czech Republic. Available online: http://www.nsoud.cz/ (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Zuklínová, M. Cui bono? Bezvýjimečně ve prospěch tohoto dítěte! Zamyšlení nad péčí o dítě. Právník 2015, 154, 97–124. [Google Scholar]

- Právo na Dětství. Available online: http://www.pravonadetstvi.cz/ (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Kornel, M. Některé problematické aspekty principu nejlepšího zájmu dítěte. Právní rozhl. 2013, 3, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Act No. 359/1999 Coll., On the Social and Legal Protection of Children. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/1999-359 (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Westphalová, L.; Holá, L. Zapojování dětí do rozhodování ve věcech, které se jich týkají, v kontextu rodinné mediace. Právní rozhl. 2019, 13/14, 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- 54/2001 Collections of the Ministry of Justice. Communication from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the adoption of the European Convention on the Exercise of Children’s Rights. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/ms/2001-54 (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Council Regulation (EC) No 2201/2003 of 27 November 2003 Concerning Jurisdiction and the Recognition and Enforcement of Judgments in Matrimonial Matters and the Matters of Parental Responsibility. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/CS/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32003R2201 (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Ministry of Justice. Available online: http://obcanskyzakonik.justice.cz/index.php/home/zakony-a-stanoviska/preklady/english (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Kapitán, Z. Participační práva dětí v praxi českého systému právní ochrany dětí, zejména justice. In Společnost Přátelská k Dětem v Obtížích; Jílek, D., Čechová, I., Eds.; Česko-Britská o.p.s.: Brno, Česká Republika, 2016; pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chrenková, M.; Cilečková, K.; Vaňharová, A. The participation of minors in the proceedings regarding thier upbringing and maintenance. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2019, 19, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Marková, I.; Šimáčková, K. Jak se téma justice vstřícné k dětem odráží v procesních postupech vrcholných soudů. In Porceedings of Zjišťování Názoru Dítěte v Soudní Praxi, Brno, Czech Republic, 17–18 May 2017; Brzobohatý, R., Ed.; Úřad pro Mezinárodně Právní Ochranu Dětí: Brno, Czech Republic, 2018; pp. 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavík, J.; Chrz, V.; Štech, S. Tvorba Jako Způsob Poznávání; Karolinum: Praha, Czech Republic, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Šporcrová, I.; Winkler, J. Potřeby dítěte a náhradní výchovná péče. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2003, 21, 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zoubková, P. Individualizace péče ve zdravotnických zařízeních pro děti do tří let a faktory organizační kultury, které ji mohou ovlivnit. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2008, 8, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Knausová, I. Teorie a Praxe Sanace Rodiny v českém Prostředí—Kvalitativní sonda do terénní práce s ohroženou rodinou v současnosti. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2011, 11, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hauková, Z. Umísťování dětí do náhradní péče o dítě. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2005, 5, 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dobešová, B. Mateřství soukromé i veřejné–případ instituce SOS dětské vesničky. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2010, 10, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Vítková, J. Možnosti sociální práce se sexuálně zneužívaným dítětem. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2003, 3, 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bechyňová, V.; Konvičková, M. Sanace Rodiny–Rociální Práce s Dysfunkčními Rodinami; Portál: Praha, Czech Republic, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Šišláková, M. Podmínky výchovy v romských sociálně vyloučených rodinách. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2005, 5, 68–84. [Google Scholar]

- Krátká, K. Integrace Romů z pohledu náhradní rodinné péče. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2003, 3, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Foltová, L. Posouzení životní situace adolescentů s psychickými poruchami. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2010, 10, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vaško, M. Pojetí podpory potenciálu rodin v nesnázích. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2020, 20, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Vaško, M. Role sociálních pracovníků z hlediska přístupů rodičů k léčbě enurézy dětí. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2018, 18, 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Janebová, R. „Ale nikomu to neříkejte…“ aneb dilema mezi sdělováním informací a mlčenlivostí v oblasti sociálně-právní ochrany dětí. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2010, 10, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Topinka, D. Optimalizace řízení systému ochrany práv dětí a péče o ohrožené děti. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2015, 15, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Divoká, L. Professionalization of Child Protection in the Czech Republic from the Perspective of Sociological Theories. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2017, 17, 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Racek, J.; Solařová, H.; Svobodová, A. Vyhodnocování Potřeb Dětí; Lumos: Praha, Czech Republic, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Glumbíková, K.; Vávrová, S.; Nedělníková, D. Optiky posuzování v agendě sociálně-právní ochrany dětí. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2018, 18, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- MoLSA. Vyhodnocování Situace dítěte a Rodiny a Tvorby Individuálního Plánu Ochrany Dítěte; MoLSA: Praha, Czech Republic, 2014; Available online: http://www.pravonadetstvi.cz/files/files/Manual-implementace-vyhodnocovani-situace-a-IPOD_MPSV.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Pemová, T.; Ptáček, R. Zanedbávání Dětí. Příčiny, Důsledky a Možnosti Hodnocení; Grada: Praha, Czech Republic, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Navrátilová, J. Proces posouzení životní situace jako zdroje ohrožení dítěte (faktory ovlivňující posouzení ohrožených dětí). Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2011, 11, 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Krchňavá, A. The participatory approach in low-threshold centres for children and youth. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2014, 14, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fučík, P.; Janků, K. Paradoxy a výzvy náhradní rodinné péče vykonávané příbuznými v sociálně vyloučené lokalitě. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2019, 19, 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gojová, A.; Gojová, V.; Lindovská, E.; Špiláčková, M.; Vondroušová, K. Způsoby zvládání chudoby a ohrožení chudobou rodinami s nezletilými dětmi. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2014, 14, 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Macela, M. Reforma systému ochrany práv dětí a péče o ohrožené děti. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2012, 12, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vávrová, S.; Vaculíková, J. Attitudes of the Czech public towards international adoption of minors. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2019, 19, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- MoLSA. The National Strategy for the Protection of Children’s Rights and the Action Plan for the Fulfillment of the National Strategy. Available online: https://www.mpsv.cz/narodni-strategie-ochrany-prav-deti-a-akcni-plan-k-naplneni-narodni-strategie (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Sodomková, L.; Šerek, J.; Juhová, D. Občanské postoje a participace u adolescentů žijících v dětských domovech. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2018, 18, 126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Macela, M. Reforma péče o ohrožené děti v České republice. Závěry nejnovějších výzkumů a jejich dopad do praxe. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2015, 15, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Víravová, J. Souvislosti a fakta o týraných a zanedbávaných dětech z diagnostického ústavu. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2015, 15, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- MoLSA. Statistical Yearbook of Labor and Social Affairs 2010; MoLSA: Praha, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- MoLSA. Statistical Yearbook of Labor and Social Affairs 2016; MoLSA: Praha, Czech Republic, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Šiška, J.; Latimier, C. Práva dětí s mentálním postižením v České republice v kontextu Úmluvy o právech dítěte OSN. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2011, 11, 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jílková, A. Podporování resilience rodin prostřednictvím projektu Asistent do rodiny. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2012, 12, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Punová, M. Konceptuální vymezení resilienční sociální práce s mládeží. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2012, 12, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jůzová Kotalová, K. Nástroje sociálně-právní ochrany dětí v praxi. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2015, 15, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rychlík, D. Systém ochrany ohrožených dětí v ČR aneb v procesu měnícího se paradigmatu. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2015, 15, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vlčková, T. Rodinné kruhy na Vysočině. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2016, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Vysloužilová, A.; Navrátil, P. Individualizace v sociální práci s rodinou–obviňování obětí. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2019, 19, 142–157. [Google Scholar]

- Gřundělová, B. Faktory ovlivňující zapojení otců v sociální práci s rodinou. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2020, 20, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Řezáč, K. Dopady diskurzů sociální práce na doprovázející organizace pěstounské péče. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2016, 16, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Navrátilová, J. Využití capability přístupu při posouzení dětského well-beingu. Sociální Práce/Sociálna Práca 2018, 18, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Šíp, M.; Hájková, M. Vzdělávání Jako Cílený Rozvoj Kompetencí. Soubor Doporučení pro Optimalizaci Systému Vzdělávání Pracovníků OSPOD; MPSV: Praha, Czech Republic, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, T.; Duramy, B.F. Enhancing Capacities for Child Participation: Introduction. In International Perspectives and Empirical Findings on Child Participation: From Social Exclusion to Child-Inclusive Policies; Gal, T., Duramy, B.F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, D.; Pramling, I.; Hundeide, K. Child Perspectives and Children’s Perspectives in Theory and Practice; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ripka, Š.; Černá, E.; Kubala, P.; Staněk, R. Pilotní Testování Rychlého Zabydlení rodin s Dětmi (Rapid Re-Housing); Ostravská Univerzita: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ripka, Š.; Černá, E.; Kubala, P.; Krčál, O.; Staněk, R. The Housing First for Families in Brno Trial Protocol: A Pragmatic Single-Site Randomized Control Trial of Housing First Intervention for Homeless Families in Brno, the Czech Republic. Eur. J. Homelessness 2018, 12, 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Vávrová, S. Children and Minors in Institutional Care: Research of Self-Regulation. In Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology (ICEEPSY), Kyrenia, Cyprus, 22–25 October 2014; Bekirogullari, Z., Minas, M.Y., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 171, pp. 1434–1441. [Google Scholar]

- Vávrová, S.; Glumbíková, K.; Gojová, A. A preliminary model of the social situation of social adjustment of homeless children. In European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology (ICEEPSY), Athens, Greece, 2–5 October 2018; Bekirogullari, Z., Minas, M.Y., Thambusamy, R.X., Eds.; Future Acad: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2019; Volume 53, pp. 232–240. [Google Scholar]

| Topic | Substitute Family (Foster) Care | Socially Pathological Phenomena | Divorce | Methods | Children’s Rights | Child Welfare System | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of Publication | ||||||||

| 2000–2009 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 25 |

| 2010–2015 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 25 |

| 2016–2020 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 21 |

| Total | 10 | 12 | 2 | 33 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 71 |

| Protection Unit | child | family | family | child |

| Role | object | object | subject | subject |

| Reasons for Protection | threat | socio-economic disadvantage, social exclusion | prevention of family failure | child’s rights |

| Protection Objectives | protection from a dysfunctional family due to family malfunction | integration | support for the family to be functioning as a whole | child’s welfare |

| Assessment | fulfilment of the child‘s biological needs and the degree of threat to the child‘s health | psychosocial needs, individual needs of the child depending on the context, risk assessment methodologies | evaluating the family strengths | the child‘s participation in the assessment, the best interests of the child |

| Intervention | sanctions, educational measures, removal of child from the family, separation of child from the family | in-home services as prevention of out-of-home placement, substitute family care, occasionally promoting system changes, case conferences, individual child protection plan | family and case conferences, participation, individual planning, building resilience, multidisciplinary approach, family therapy | with regard to account the best interests of the child |

| Key Critical Themes | issue of adequacy of the use of out-of-home placement based interventions, deprivation syndrome in children without a family background | critique of the effectiveness, discussion of social work limits in promoting system changes, neglect of “ordinary” families, distrust of in-home services, tensions between the state and NGO sectors, split in the profession | lack of available services, lack of time for preventive activities, transfer of state responsibility to NGOs, failure to clarify the roles between “control” and “support” bodies, quality standards, reflexivity of workers | individualization, loss of family ties as a source of help, lack and fragmentation of services, different approaches to the needs and rights of children, declarative nature of legislation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gojová, A.; Gřundělová, B.; Cilečková, K.; Chrenková, M. Path toward a Child-Centered Approach in the Czech Social and Legal Protection of Children. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218897

Gojová A, Gřundělová B, Cilečková K, Chrenková M. Path toward a Child-Centered Approach in the Czech Social and Legal Protection of Children. Sustainability. 2020; 12(21):8897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218897

Chicago/Turabian StyleGojová, Alice, Barbora Gřundělová, Kateřina Cilečková, and Monika Chrenková. 2020. "Path toward a Child-Centered Approach in the Czech Social and Legal Protection of Children" Sustainability 12, no. 21: 8897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218897

APA StyleGojová, A., Gřundělová, B., Cilečková, K., & Chrenková, M. (2020). Path toward a Child-Centered Approach in the Czech Social and Legal Protection of Children. Sustainability, 12(21), 8897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218897