1. Introduction

This study aims to empirically examine the relationship between social entrepreneurship and regional economic development, using data on certified social enterprises in South Korea. For this purpose, research models were developed by first examining theoretical discussions on social entrepreneurship and regional economic development.

In response to the global financial crisis of 2008 and its impact on the economy, many countries increased their spending in order to promote economic growth and sustainable economic development. However, increased government spending caused massive financial deficits in many countries. Each country carried out multifaceted efforts to resolve massive financial deficits caused by increased government spending in the process of overcoming fiscal and financial crises [

1,

2,

3]. Nevertheless, the measures taken, based on two extreme (dichotomous) approaches of existing state-led and market-driven methods, instigated market and government failures and led to heavy questioning concerning their effectiveness. Therefore, it became necessary to find new alternatives that could solve fiscal deficit issues, a stagnant market, and unemployment all at the same time. In particular, in the area of social welfare, the integrity of welfare provision spending emerged as an important issue. What developed as an alternative was the expansion of welfare service provisions and the creation of new jobs through stimulating the social economy and ultimately achieving sustainable economic development [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

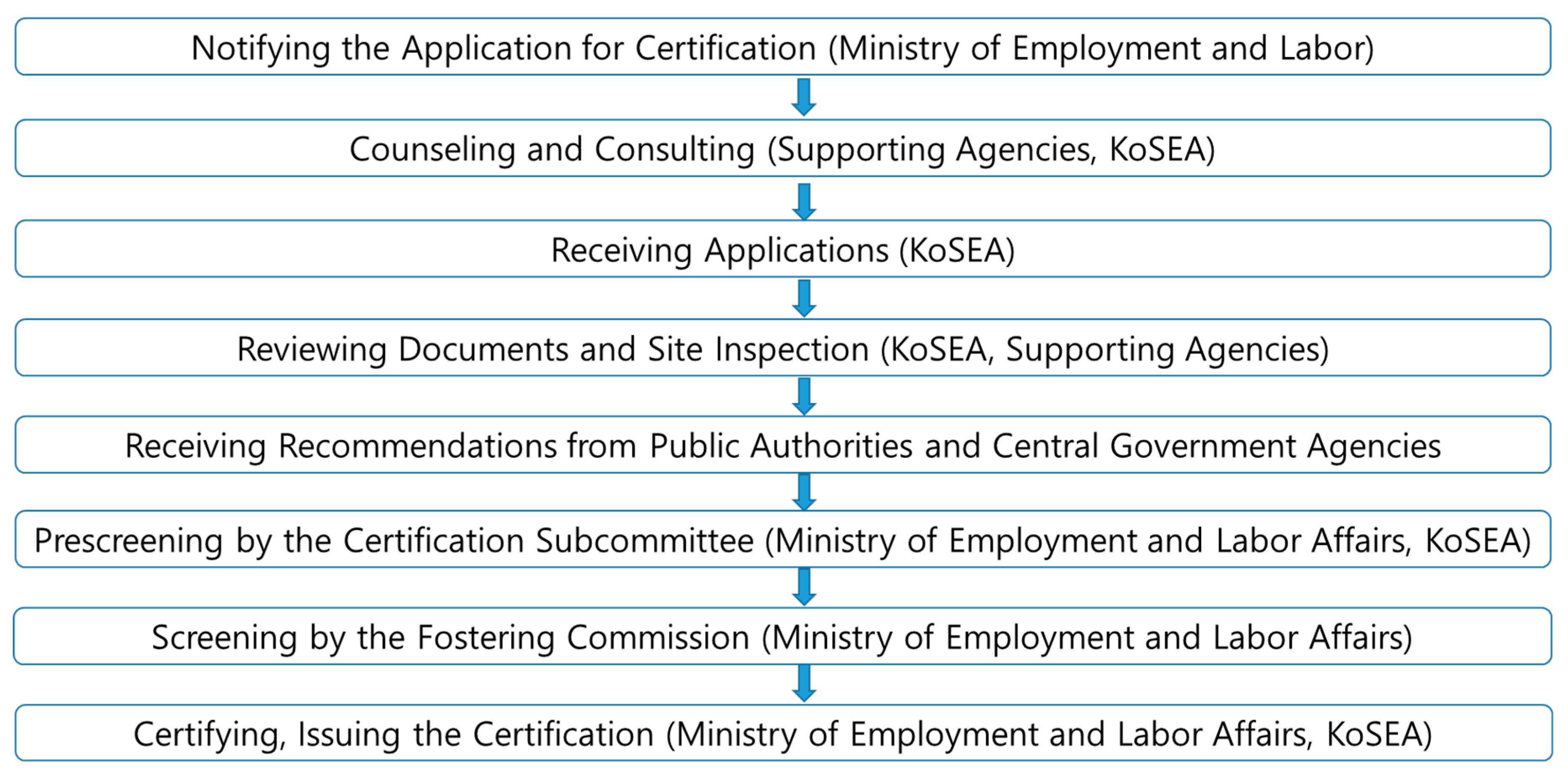

South Korea, an OECD member, has made direct investments in its social economy to mount a new response to the global economic crisis, welfare state decline, and social challenges. In particular, South Korea has mainly developed social enterprises among various operators in the social economy. Social enterprise is an organization established based on social entrepreneurship to pursue social and economic objectives. As a response to the global economic crisis and welfare state decline, the Korean government introduced a plan to support social enterprises. To provide services and work opportunities for socially excluded people, the Korean government enacted the Social Enterprise Promotion Act (SEPA) in 2007. Based on SEPA, a company or organization must go through seven steps before being certified as a social enterprise in South Korea.

According to a press release in 2020 by the Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency, the Korean government had approved 3125 social enterprises as of 30 September 2020. Because subsidies are typically required in the start-up phase of a social enterprise [

10], South Korea increased the budget by about 53.348 million US dollars in 2016 (about 0.013% of the central government’s total expenditure, equaling approximately 398.5 billion US dollars) to provide social enterprises with financial and managerial support. The Korean government is also actively promoting local government attempts to foster and support social enterprises that meet the specific needs of local communities by allowing local governments to identify preliminary social enterprises and establish regulations at the local level to foster them. Job creation, unemployment reduction, and regional economic development through vitalization of social enterprises had been emphasized more and more in correlation with the ‘Creative Economy’ measures of the Park Geun-hye administration. As a result, by the end of September 2020, there were 2626 certified social enterprises that were currently active, showing a remarkable growth from the 55 certified social enterprises that were active in 2007.

Despite the increasing numbers of government-driven social enterprises established based on social entrepreneurship and financial support from public and private organizations for them in South Korea, neither an evaluation of the performance of social enterprise programs, based on regional economic development, nor explicit strategies for social enterprises have been proposed. Because some of the Korean government’s key roles are job creation and sustainable regional economic development, various forms of support including government subsidies are given to the social enterprises with official recognition. Since proving the effectiveness of external funding is critical in order to allocate limited resources as efficiently as possible, evaluation of the social enterprise policy of the Korean government is a necessary task to promote regional economic development. Despite the need for such research, experiential and empirical studies on this matter are quite scarce in South Korea. Existing studies on social enterprises in South Korea (e.g., [

11,

12,

13,

14]) focus on job creation using data on certified social enterprises. Such studies are crucial to government efforts to create new jobs for the underprivileged. However, these studies are limited in that they do not take into account the role(s) of social enterprises in regional economic development.

This study aims to address the limitations of prior studies by empirically examining the relationship between social entrepreneurship and regional economic development through focusing on the role of government-driven certified social enterprises in regional economic development in South Korea. To frame our query, this study considers prominent theories on regional economic development, focusing particularly on arguments related to physical capital, human capital, knowledge, and entrepreneurship, and on associated conceptualizations of social entrepreneurship. The result of the analysis in this study is expected to present important implications for establishing future directions for policies regarding social enterprise support for regional economic development.

This paper is structured as follows. The next Section reviews the literature on social economy, social entrepreneurship, social enterprise, the relationship between social entrepreneurship and regional economic development, and social enterprise policy initiatives implemented by the Korean government. The third Section explains the data, variables, and method for the empirical analysis. After interpreting the empirical results, we conclude with a discussion and list of policy implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Economy, Social Entrepreneurship, and Social Enterprises

Since the rise of the social economy has been recognized in political, economic, legal, administrative, and other circles, ‘social economy’ has become a useful term for academics and researchers. According to Spear (2013), “the social economy is typically understood as a family of different types of organizations: co-operatives, mutuals, associations, and foundations (CMAF)” [10: 8]. The social economy plays an important role in assisting the most disadvantaged in society in many countries. It has been expected to present a new alternative to government-provided public service initiatives and to contribute to resolving social issues such as unemployment and poverty [

15,

16,

17].

In the social economy, active participation of social entrepreneurs has become increasingly important for social and economic development through the expansion of welfare service provisions and the creation of new jobs [

18,

19]. Social entrepreneurs have the capabilities and temperament for a set of exceptional behaviors. Since social entrepreneurs are searching for innovative solutions to meet new social needs and to develop a new response to social challenges, social entrepreneurship is often associated with social innovation [

20,

21,

22]. Although the initiatives of social entrepreneurs result in the establishment of various kinds of innovative organizations, social enterprise can be seen as a general form of economic organization operating within the social economy [

7,

23,

24] and it refers to one of the tangible outcomes of social entrepreneurship.

Many studies and discussions about social enterprises have taken place along with their rapid growth. However, despite the existence of research highlighting the cross-sectoral nature of social enterprise, scholars have conflicted over its definition [

25,

26,

27,

28]. This is largely due to the fact that social enterprise in each country has developed from different origins and in a different manner, thus creating a wide range of models [

29,

30]. Although it is difficult to clearly define a social enterprise, most scholars have generally agreed that a social enterprise denotes an economic agent that pursues public interest objectives of production and supply of social services, as well as the traditional corporate objective of maximum profit at the same time [

31,

32,

33,

34]. In other words, social enterprise can be viewed as economic entities creating social and economic value within the social economy [

23,

35,

36]. Thus, a social enterprise is regarded as a hybrid between nonprofit organizations pursuing social goals and businesses pursuing economic goals [

18,

19,

37] or a hybrid providing state services [

30,

38,

39].

The OECD broadly defines a social enterprise as an organization established based on entrepreneurship to pursue social and economic objectives, which, in a narrower sense, promotes regional economic development by re-integrating the labor market through training of the poor and by consuming the products and utilizing services produced in the process [

40]. Defourny (2001) explains the concept of social enterprise separately in terms of both economic and social dimensions [

25]. He explains that a social enterprise, in the economic sense, should take some level of risk while continuously producing or selling goods and services, have a high degree of autonomy, and retain a minimum number of paid workers. He also describes that in the social sense, a social enterprise is formed based on citizens’ voluntary participation; its decision-making authority should not be determined based on ownership of capital; parties affected by the social enterprise’s activities should be able to participate in decision-making; and profit sharing should be limited. In this perspective, a social enterprise, unlike private companies, has public interest, and its concept of social enterprise is also clearly distinct from that of the social responsibility of corporations.

It has been said that social enterprises emerged as an alternative to resolve market and government failures [

14]. In other words, it can be said that out of the three sectors of the economy, a social enterprise performs broad activities within the spectrum of the social economic sector, which is the third sector that has the properties of the first sector—public area (state)—and the second sector—private area (market). Therefore, it can be said that social enterprise seeks to achieve social goals through commercial activities [

18,

19,

37,

41,

42,

43] and plays a key role in providing the state services [

38,

39].

However, countries in Europe do not subscribe to this model and view both the third and fourth sectors as the social economic area. According to scholars who advocate a fourth sector distinct from the third (e.g., [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49], the third sector represents citizen groups and non-government, non-profit organizations; whereas the fourth sector is defined as a new collective organizational model that simultaneously seeks profit and public interests, and combines the existing sectors to resolve social issues. These scholars include social enterprises in the fourth sector and suggest that social enterprise is an important economic agent that functions within the fourth sector. In addition, Williams (2008, 2010) presents the fourth sector as an area for non-official, volunteer activities and a form of citizen participation culture that can supplement the public activities of the third sector [

44,

45]. Jimenez and Morales (2011) also argue that it is a collective sphere that combines public, private, and civic sectors for the purpose of resolving social issues, and economic agents like social enterprises, cooperatives, and township enterprises are main constituents of the fourth sector [

48].

Taken together, social enterprise is an important form of economic organization working within the social economy. Each country’s government exerts multifaceted efforts to meet social service needs through vitalization of social enterprises, although the contents and methods of support differ by country [

50,

51,

52].

2.2. Social Entrepreneurship and Regional Economic Development

Recent entrepreneurship literature has emphasized the innovative capacity of social entrepreneurs as new actors for social and economic development [

20]. Thus, social entrepreneurship is an important factor for the development of the social economy and contributes to regional economic development. For example, social economy organizations are often the biggest employers in the area of economic crisis in East Germany; in fact, the organizations are some of the most important actors for regional economic development in almost all European crisis regions [

53]. Therefore, the significance of social entrepreneurship for keeping some such thing as a locality or community alive has been emphasized in terms of regional economic development [

53].

It is clearly not easy to identify the main actors in the social economy because of the marked diversity of national realities concerning the concepts and the level of recognition of the social economy [

9]. Nevertheless, it can be said that nowadays, the organizations that represent the social economy in Europe are cooperative family, family of mutual societies, family of associations and social action organizations, and platforms for social enterprises [

9]. These organizations can contribute to the creation of jobs and entrepreneurial ventures in disadvantaged regions [

11]; therefore, they can have an influence on regional economic development.

As mentioned above, social enterprise can be seen as a general form of economic organization operating within the social economy [

7,

23,

24] and it refers to one of the tangible outcomes of social entrepreneurship, although the initiatives of social entrepreneurs result in the establishment of various kinds of innovative organizations. The presence of social enterprises in regions where public services are poor or lacking is particularly important because it provides social services or jobs to the socially underprivileged while producing and selling goods and services; promotes social values that are difficult to provide through the market mechanism; and retains the attributes and profit-driven nature of a corporation and social nature that seeks to fulfill public interests [

11]. Social enterprises seek to add to regional economic development through the creation of jobs and entrepreneurial ventures in disadvantaged regions. By helping to improve the overall skills of a local workforce, reducing inequalities in access to health and social care services, constructing good-quality housing for those living in sub-standard conditions, reducing social exclusion for the unemployed, creating wealth and adding benefits due to a multiplier effect, improving labor productivity due to skills investment, increasing tax revenues while reducing welfare payments, and enabling community-led rejuvenation and renewal, social enterprises can also provide economic development benefits to poor regions [

54]. Thus, social enterprise was expected to present itself as one of the new alternatives to expand welfare service provisions, creation of new jobs, and reduction of unemployment and poverty in such regions through stimulating the social economy and ultimately achieving sustainable regional economic development [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

15,

16,

17,

23,

24]. Recent data from CIRIEC (2012) actually show that the social economy actors including social enterprise have increased their share of employment within Europe [

55]. For this reason, some countries like South Korea have promoted supporting social enterprises and have increased the budget to provide social enterprises with financial and managerial support. The social enterprise of South Korea is a typical case of government-driven social enterprise because it has grown under the benefits of government-led development policies, mainly represented by government certification and support towards personnel expenses. In addition, infrastructure access, information, consultancy, and technical support are available for the certified social enterprises in South Korea.

In general, improvement in the efficiency of resource allocation, equity through redistribution, economic stability, and growth accomplishment can be considered as bases for government intervention in the private sector’s economic activities [

56]. Each government’s active financial support of social enterprises can be interpreted as a pursuit of equity through redistribution and economic stability and development. For example, the Korean government actively fostered social enterprises in order to seek equity through redistribution by providing social services to the underprivileged, and to pursue sustainable economic development through regional economic vitalization by providing sustainable jobs, thereby promoting job creation and increased employment. The increase in employment and job creation represents economic stability. Since Korea’s 1997 financial crisis, job creation and increased employment were imperative to alleviating the economic downfall at hand, so a fundamental goal for creating a comprehensive policy was in place. Based on the aggressive funding of social enterprise, it is possible to infer that the Korean government has regarded the objective of job creation as highly important.

Another way for evaluating the government’s financial support for social enterprises is by measuring improvement in the efficiency of resource allocation. Identifying the two axes that make up modern society as the market and the government, we can say that efficient allocation of resources is primarily the responsibility of the market. Government interventions to achieve efficient resource allocation are justified only when the market fails to do so—that is, when a market failure occurs [

57,

58,

59]. In this respect, the socially disadvantaged would be unable to obtain decent employment and continue to be placed in vulnerable situations, if their employment is determined solely by the market. Therefore, the government seeks to enhance equality by providing various welfare benefits to the socially disadvantaged through income redistribution policies. However, it is necessary to ultimately inspire the socially disadvantaged to desire to work and be independently active in the market. It is difficult, practically, for the government of a welfare state to afford the continually increasing costs of welfare in the face of a crisis. Hence, vitalization of social enterprises that can provide the socially disadvantaged with sustainable employment and social services at the same time can be an essential alternative for the government. In the case of Korea, such legitimacy of government intervention became the basis for state-led support for social enterprises, and as a result, enabled a rapid quantitative growth in a short time through certification and labor cost support. Moreover, the method of supporting labor costs was a practical way to recruit talent for the immediate implementation of certain projects and became the most powerful force behind the integration of labor among the underprivileged, development of social service providers, and the creation of jobs [

60].

However, a social enterprise can also be regarded as a social venture that is operated based on the principles of profit generation and innovation typical of general for-profit corporations, while at the same time pursuing the social objectives of alleviating social problems and market failures or creating social values. Therefore, a social enterprise utilizes creative entrepreneurship, innovation, and market principles to create social values and encourage social changes. Considering these perspectives, the government’s direct financial support for social enterprises, such as the support for labor costs, may contribute to job creation and social service provision through the establishment and maintenance of social enterprises in the short term. In the long term, though, it could act as a hindrance to the development of social enterprises or distort the fundamental attributes of a social enterprise. Under such conditions, it is difficult to promote independence and autonomy of social enterprises and the development of diverse social enterprises may also be inhibited. Sustainability issues have also been shown to exist for less competitive social enterprises, as most social enterprises have scaled down on employment once support for personnel expenses expired, while others disposed of their assets or even closed business. Despite these issues, there is a general consensus that financial support, such as support for personnel expenses, enables the establishment and maintenance of social enterprises in the short term, thereby contributing to job creation and regional economic development [

4,

27,

32,

33,

34,

61].

South Korea’s support policy for social enterprises is expected to promote the quantitative and qualitative development of social enterprises and ultimately contribute to regional economic development. To corroborate such theoretical arguments, an empirical study on whether social enterprises are actually contributing to regional economic development is needed. So far, there are virtually no previous studies available.

Based on the limitations of previous studies and the above discussion, this study seeks to answer the following research question. Social entrepreneurship is a vital factor for promoting regional economic development and therefore I asked, “what effect does social entrepreneurship have on regional economic development?” Thus, this study addresses the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Regional economic development is positively affected by social entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). After controlling physical capital, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship has a positive impact on regional economic development.

This study uses a model to investigate the relationship between government-driven social enterprises and regional economic development. Before moving on to specific analyses of the relationship, support policies and the general status of social enterprises in Korea will be briefly examined below.

2.3. Social Enterprise Policy in South Korea

In Europe, interest towards social enterprises—along with the trend of privatization of social welfare and job creation—began to rise in the 20th century. In South Korea, on the other hand, the government did not begin to actively promote the expansion of social services and job creation until the 1997 financial crisis. At that time, it did so in an effort to overcome the economic crisis, to resolve social welfare problems, and to promote economic development [

52]. The government’s increased interest and investment in this area can be clearly seen in data from the years following that crisis: A budget of about 7.3 million US dollars created approximately 2000 social enterprise jobs in 2003, and a budget of about 1.3 billion US dollars created approximately 162,000 jobs in 2011 [

62]. In other words, to overcome the economic crisis, to provide social welfare services, and to promote economic development in regions where public services are poor or lacking, the Korean government introduced the social enterprise model as an alternative. It even enacted a special ‘Social Enterprise Promotion Act’ in 2007.

With rapid aging and the dismantling of the traditional family structure, public demand for social services rapidly increased. Under the government’s lead, certification of social enterprises began, and starting in August 2012, revised statutes of the ‘Social Enterprise Promotion Act (SEPA) of 2007′ were implemented. Financial and operational support was provided to certified social enterprises. In December 2012, the Social Enterprise Promotion Agency was established. In addition to central government support, an ‘ordinance on standards for social enterprise development support’ was enacted to encourage local governments to enact ordinances to foster and support social enterprises at the regional level. By planning for quality improvement in certification services and supporting fair certification screening, the Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency (KoSEA) contributes to the expansion and invigoration of social enterprises.

Figure 1 shows procedure for certification of social enterprises in South Korea.

As activities of government-driven social enterprises are generally based on local governments’ administrative districts, the enforcing agency was changed from the central government to local governments [

11]. Hence, the central and local governments have been providing various types of support to social enterprises based on the SEPA and other relevant laws and ordinances. The Labor Department in particular aims to foster approximately 3000 social enterprises by 2017.

According to the revised SEPA, a social enterprise is a corporation that pursues social objectives, such as enhancing the quality of life of local residents, by providing social services or employment opportunities to the underprivileged or contributing to the local community, while simultaneously producing and selling goods and services that meet appropriate requirements and have been certified. The Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency provides specific examples of underprivileged groups, such as low-income individuals, the disabled, victims of sexual trafficking, the elderly, those who have been unemployed for a long period, and women who have taken a career break. Thus, a social enterprise in South Korea is different from that of Europe or other countries in terms of concept, characteristics, and function. Specifically, social enterprises in South Korea, unlike in other countries, have grown under the benefits of government-led development policies, mainly represented by government certification and support towards personnel expenses.

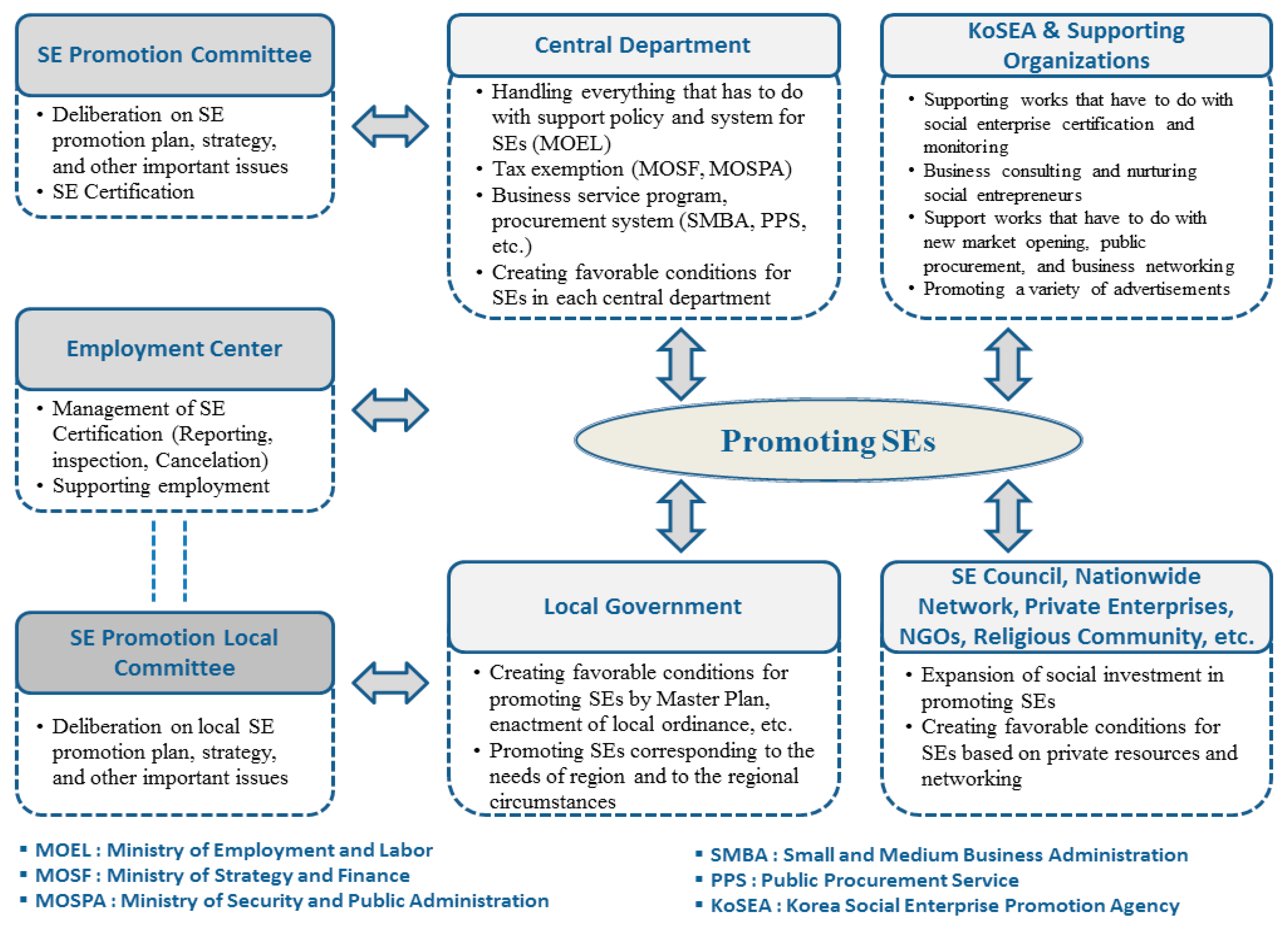

Figure 2 roughly shows South Korea’s development policy for social enterprises.

The support for social enterprises in Korea can be separated into the central government and the local government levels as follows. At the central government level, certified social enterprises are provided with management support, training support, facility cost support, priority purchase for public agencies, tax exemption, social insurance premium assistance, funding for social-service-providing enterprises, and employment liability exemption and tax reduction for affiliated companies. At the local government level, with some variation by logicality, various policy efforts are made to help region-based preliminary social enterprises meet the certification requirements at an early stage by providing management consulting, personnel expenses for new and professional recruitments, business development costs, priority purchases, and pro bono assistance. In addition, organizations such as the Korea Business Council of Social Enterprise, Work Together Foundation, Korea Foundation for Social Investment, and Social Solidarity Bank, provide support at the national level while social enterprise support centers of metropolitan municipalities or primary local governments provide assistance at the local level.

Although central and local governments provide a wide variety of support to certified social enterprises and region-based preliminary social enterprises, a majority of the associated budget is allocated for personnel expenses for creating jobs [

11,

52]. This trend has existed since support for social enterprises began, as they were aggressively fostered to alleviate unemployment and to provide decent employment opportunities to the underprivileged. Currently, the social enterprise development policies for both the central and local governments are focused on how many jobs will be created and on promoting regional economic development through future job creation. It implies that social enterprises are gaining attention as a viable means of job creation in an era of rising unemployment.

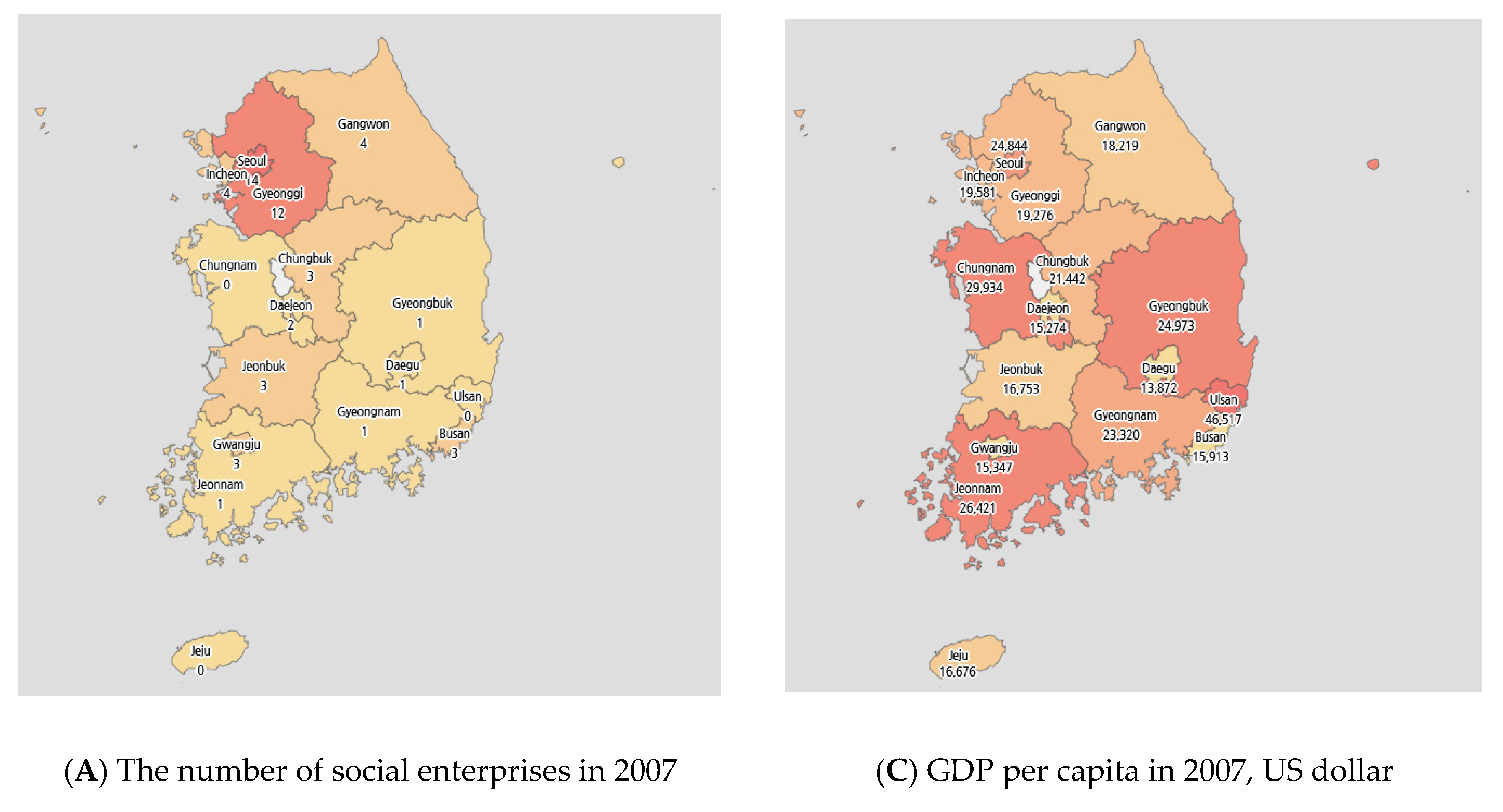

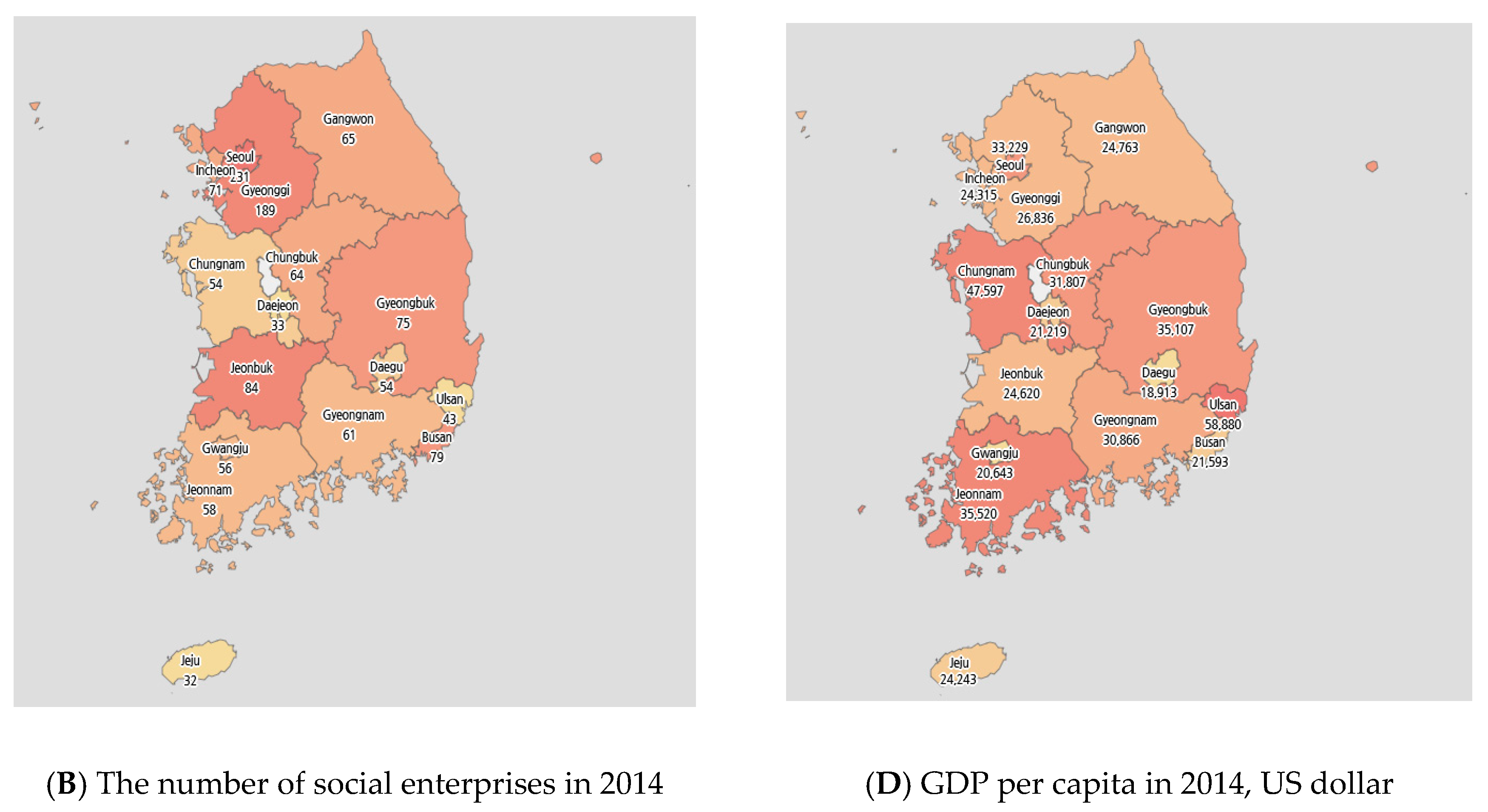

In South Korea, certification status is a particularly important element, considering the country’s unique government-led development process by way of certification and personnel expense assistance. According to a study by Kim and Lee (2012a) [

11], in the early phase of certification, a high percentage of organizations transitioning into social enterprises were ones that started in the job creation project led by the central government under the Ministry of Employment and Labor. However, more recently, related government agencies under the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Ministry of Employment and Labor are actively discovering and fostering social enterprises in the areas of agriculture and fishery and arts and cultures. As of the end of 2016, approximately 40% of all social enterprises were based and operated in the metropolitan areas of Seoul, Incheon, and Gyeonggi, all of which have large populations.

Table 1 indicates the annual status of applications, certification rates, and maintenance rates since 2007 when the certification program was implemented.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Empirical Model: Regional Economic Development Model

Quite a number of theoretical discussions of regional economic development have been made to this day. In particular, the arguments made by a variety of social scientists, including economists, state that physical capital, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship are important factors in regional economic development [

65].

Physical capital, as emphasized from the primitive age to the information society of the modern era, is a fundamental element of personal and social development and economic growth. Human capital has developed as an important factor along with physical capital as the creative ideas of humans began to gain property value with the maturation of industrial society. Highlighting this, neoclassical economic growth theorists such as Robert Solow (1957) [

66], advocated the diminishing marginal product of capital and labor and stressed the qualitative and quantitative enhancement of human and physical capital.

Endogenous growth theorists, such as P.M. Romer (1986) [

67] and R. Lucas (1998) [

68], advocated the importance of knowledge and changes in technology and attempted to explain a portion of the Solow residual—the part of growth that cannot be explained by capital accumulation or increased labor input. New knowledge creation and transfer through R&D investments are important for innovation and economic development. Scholars like T.W. Schultz (1967) [

69] and G.S. Becker (1975) [

70], who stressed the importance of human capital, claimed that the accumulation of human capital through education ultimately contributes positively to sustainable economic development and tried to explain another portion of the Solow residual. Moreover, they stated that innovation through entrepreneurship (as measured by new firm formation) is an essential factor that can lead to sustainable economic development and explain a certain portion of the Solow residual. Over the years, a variety of arguments have been put forth to address this issue. Each government, irrespective of country, has been accounting for regional and local factors that affect entrepreneurship. This is because entrepreneurship has been regarded as one of the important drivers of sustainable economic development and growth in this current knowledge-based economy [

71,

72,

73,

74].

The belief that social entrepreneurship can enable local communities to resolve their own issues and integrate underprivileged groups into the community is even more strongly held in the new governance era of today. In particular, each government puts great importance on the potential contribution of social enterprises towards economic development, as the third sector contributes to the creation of social and economic values through many kinds of activities [

23,

35,

36]. Thus, this study examines the relationship between the level of regional economic development and social entrepreneurship (as measured by the number of social enterprises), focusing on government-driven certified social enterprises in each region. For this, the level of regional economic development is used as a dependent variable and the number of certified social enterprises in each region as an explanatory variable. Additionally, physical capital, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship that may have an influence on regional economic development are used as control variables.

The physical capital, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship, used as controls in this study, are variables that are chiefly used to describe regional economic development. Numerous existing studies have used values or ratios representing the natural logarithm of each variable. Thus, this study used natural logarithm values for physical capital, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship.

This study examines the relationship between social entrepreneurship and regional economic development by using time-sequential panel data collected over an 8-year period from 2007 to 2014. In the course of the panel regression analysis, both a fixed-effect model and a random-effect model were used to interpret results and determine which model is more appropriate. Before exploring the relationship between social entrepreneurship and regional economic development by the panel regression analysis, this study also analyzes the relationship between social entrepreneurship and regional economic development by the pooled regression model. Equations (1) and (2) below indicate the pooled and panel regression analysis models used in this study. Using a specification of the Cobb–Douglas production function type generally used in previous empirical studies on regional economic development, this study augments a production function with social enterprise.

In Equations (1) and (2), indicates the level of economic development of region i, and represents social entrepreneurship measured as the number of certified social enterprise in region i during period t. represents the estimated coefficient values of regional certified social enterprise variables in the model; that is, an increase of the regional certified social enterprise variable by one percent correspondingly increases the left-hand side (regional economic development) by percent. , , , and represent coefficient values of physical capital, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship, respectively. Because the level of regional economic development can be affected by regional characteristic variables as well as regional social enterprise, this study includes physical capital, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship as control variables in the model. Finally, represents the error term.

3.2. Data and Variables

The key variable for this study is government-driven certified social enterprises funded by central and local governments in South Korea. The Korean government started to support social enterprises with public funding in 2007. This study explores the relationship between government-driven certified social enterprises and regional economic development from 2007 to 2014. Due to the limitations in obtaining data, this study uses the data on the certified social enterprises generated by the Ministry of Employment and Labor of Korea in recent years.

The temporal scope of this study is from 2007, when certification of social enterprises began, up to the end of 2014. In this study, the analysis of the relationship between government-driven social enterprise and regional economic development centers around the period between 2007 and 2014. The spatial extent of this study is nationwide, including 16 key metropolitan region-levels.

Indicators for the other basic variables were drawn from a variety of sources. To collect data on other indicators that are not covered by the Ministry of Knowledge Economy of South Korea, this study uses data on gross regional domestic product per capita, gross fixed capital formation, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship from the Korea National Statistical Office. For ease of reference, the basic variables are summarized in

Table 2, which also shows a brief description and the data source of each variable.

5. Discussion

While questions about social entrepreneurship effects can be answered only through conducting empirical studies in a variety of policy contexts, researchers in the area of social entrepreneurship have not adequately tested propositions related to social entrepreneurship effects in regional economic development and are still at an early stage in this research field. As one of only a few empirical studies that has examined social entrepreneurship effects in regional economic development, this study contributed to this research field by exploring effects of social entrepreneurship in regional economic development using objective measure such as gross regional domestic product per capita and the number of certificated social enterprise in South Korea. In particular, to explore the relationships between social entrepreneurship and regional economic development, this study presents a framework that illustrates the theoretical causal relationship between social entrepreneurship and regional economic development; and then analyzes the impact of social entrepreneurship on regional economic development by using data on certificated social enterprises in South Korea. The following summarizes the empirical results from pooled OLS, fixed-effect, and random-effect regression models, which simultaneously control for factors that are theorized to affect regional economic development.

First, results of the fixed-effect and random-effect regression models suggested that the regional GDP per capita increased as the number of regional certified social enterprises increased, indicating that a growth in the number of social enterprises contributes positively to regional economic development. It means that social enterprise start-up and operation contribute to promoting regional economic development. This result is in line with previous studies [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

15,

16,

17,

23,

24,

27,

32,

33,

34,

61] on social enterprise. In this study, the use of longitudinal study designs helps us better understanding the impact of social entrepreneurship measure as the number of certified social enterprise on regional economic development. Evidence from this study could strengthen and modify the framework, as reliance of previous empirical studies on results from cross-sectional studies in its development is undoubtedly a limitation.

Second, based on results of fixed-effect and random-effect regression models, this study also found that regional economic development variables such as physical capital, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship contribute to regional economic development. This supports arguments made by previous studies based on neoclassical economic growth theories (ex. [

66]), endogenous growth theories (ex. [

67,

68]), human capital theories (ex. [

69,

70]), and entrepreneurship theories (ex. [

71,

72,

73,

74]). Therefore, the results from this study tie well with the argument made by the variety of social scientists, including economists, state that physical capital, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship are important factors in regional economic development [

65].

Third, the results suggest a new direction for policy that focuses on instruments to promote regional social entrepreneurship in a region. The results of this study also imply that governments of each region should put forth an effort to implement policies to promote sustainable regional economic development and growth by actively fostering social enterprises there. Because each local government possess the ability to efficiently respond to the immediate needs of social enterprises in their regions, they need to make efforts to promote regional economic development through social enterprise policies.

Since much of the importance of social enterprises comes from their ability to reintegrate into the workforce people from disadvantaged backgrounds, it would also be necessary to measure the impact of social enterprise on the general unemployment rate and, in particular, the rate of unemployment among people with lower levels of education. Because of data unavailability, it was not possible to measure the impact of social enterprise on the rate of unemployment among people with lower levels of education. Alternatively, this study tried to measure the impact of social enterprise on the general unemployment rate of each region by using pooled OLS regression model and panel regression models (fixed-effect and random-effect models). However, the coefficients of social enterprise in regression results by using all empirical models were not statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. Specifically, the value of the regression coefficients of social enterprise for regional unemployment rate were 8.7304 (p = 0.055) in pooled OLS regression result, −2.0664 (p = 0.479) in fixed-effect panel regression result, and −1.1162 (p = 0.694) in random-effect panel regression result, respectively, although the empirical results on the impact of social enterprise on regional unemployment rate were not provided in detail in this study. Thus, more empirical research on the relationship between social enterprise and regional unemployment rate and especially the rate of unemployment among people with lower levels of education is needed in the future.

In addition, it is recommendable to isolate the effect of social enterprise from the effect of other factors; therefore, author of this study included a set of interaction variables in all empirical models such as pooled OLS regression model and panel regression models (fixed-effect and random-effect models) after generating new variables that reflect interactions between social enterprise and physical capital, between social enterprise and human capital, between social enterprise and knowledge capital, and between social enterprise and entrepreneurship. However, all regression results show that social enterprise is not statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. For better understanding of the relationship between social enterprise and regional economic development, follow-up empirical studies considering a variety of interaction effects among social enterprise, physical capital, human capital, knowledge capital, and entrepreneurship are needed in the future.

The South Korean government borrowed the general policy direction and the particular regulatory device from UK social enterprise policy; however, it failed to learn about the specific contexts of the UK policy and to attempt two-way communication with domestic stakeholders [

30,

39]. As a result of the failure, a distorted social enterprise policy transfer took place, and the Korean government’s social enterprise policy has been biased toward the perspective of the government, not that of stakeholders such as the socially disadvantaged and vulnerable. As mentioned, South Korea has mainly developed social enterprises among various operators in the social economy in response to the global economic crisis and welfare state decline. Thus, the Korean government introduced a plan to support social enterprises and enacted the Social Enterprise Promotion Act (SEPA) in 2007 to provide services and work opportunities for socially excluded people such as the elders, low-income people, working poor, etc., and the ageing population. However, the South Korean social enterprise policy has been biased toward the perspective of the government. The distorted social enterprise policy transfer was caused by the centralized power structures, legacy of top-down control, and one-way communication of the Korean government [

30]. A top-down approach with strict controls in centralized power structures is less likely to contribute to social entrepreneurship and innovation. Thus, the South Korean government needs to consider two-way communication with stakeholders to foster better understanding on both sides, although the government’s current social enterprise policy has been shown to contribute to regional economic growth as it. The South Korean government needs to be more focused on social enterprise policies based on the needs of the socially disadvantaged and vulnerable rather than a broader response to unemployment in the future.

Finally, unlike in Europe and other countries, social enterprises in South Korea were institutionalized to solve employment and poverty issues of the working poor. They will likely be an alternative to labor market policy, which is inevitably underscored in an aging society with poverty issues among the elderly. Aging faster than western societies, South Korea is facing problems with employment and welfare, including workforce reduction, reduced productivity, and an increased fiscal burden. Therefore, an employment strategy for the elderly in the area of social economy is an important policy measure necessary for employment stability and social welfare. In this perspective, the development of regional social enterprise for the elderly is to be recommended as one possible method to help solve the problems of employment and welfare for the elderly in South Korea. Also, more empirical research on the role of senior social entrepreneurship in regional economic development is needed in the future.