The Role of Travel Motivations and Social Media Use in Consumer Interactive Behaviour: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Uses and Gratifications Theory and Social Media

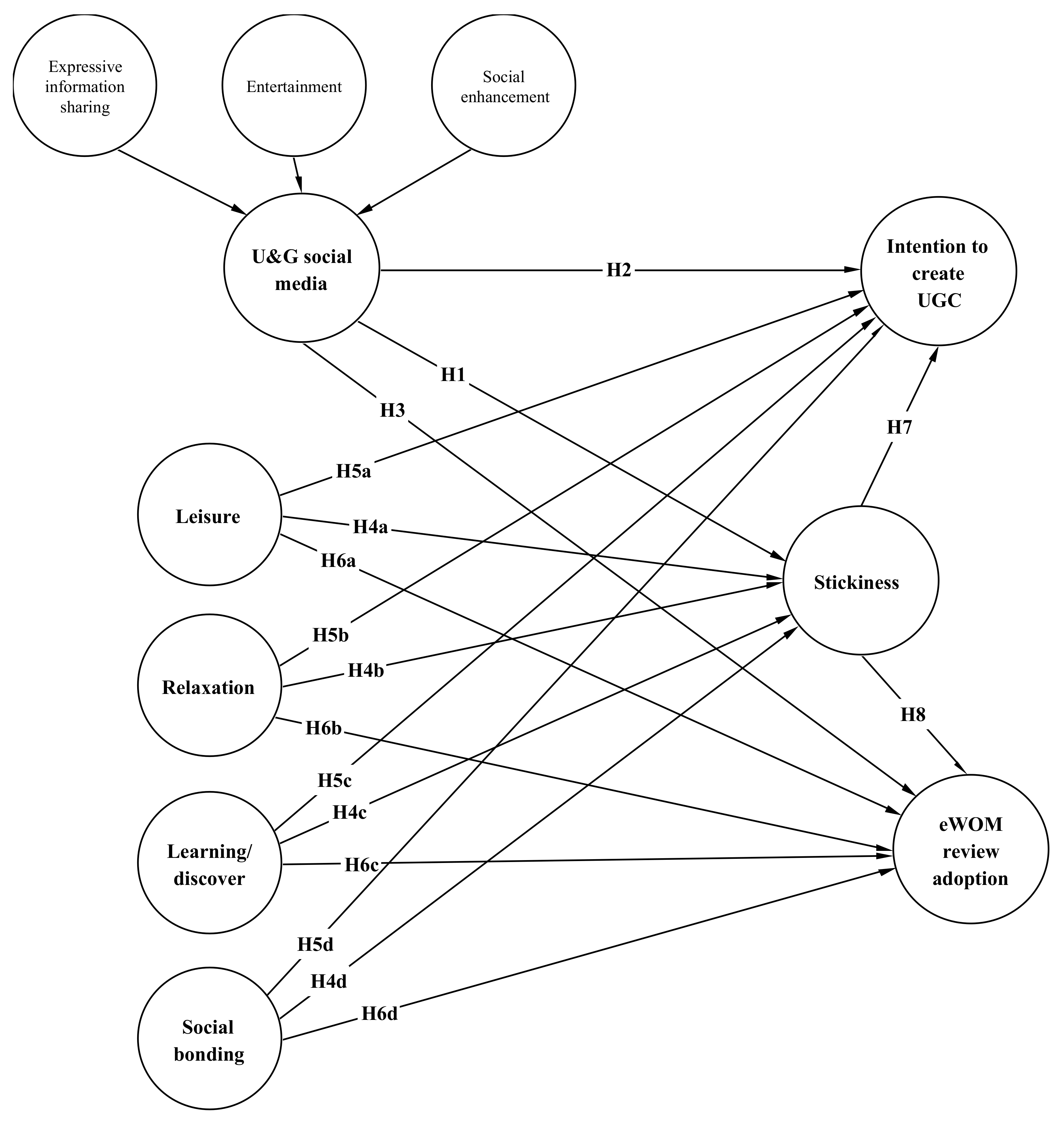

2.2. Effects of the Gratifications Provided by Social Media Use on Consumer Interactive Behaviour

2.3. Travel Motivations and Consumer Interactive Behaviour

2.4. Stickiness, User-Generated Content, and eWOM Review Adoption

3. Methods

3.1. Study 1: Concept Mapping

3.2. Study 2: Online Survey

3.2.1. Design and Sample

3.2.2. Measures

3.2.3. Psychometric Properties of the Measurement Instrument

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Narangajavana Kaosiri, Y.; Callarisa Fiol, L.J.; Moliner Tena, M.A.; Rodriguez Artola, R.; Moliner Tena, M.A.; Sanchez Garcia, J. User-Generated Content Sources in Social Media: A New Approach to Explore Tourist Satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2017, 58, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J. The Influence of Authenticity of Online Reviews on Trust Formation among Travelers. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, E.; Ruiz, C.; Curras-Perez, R. Destination Appeal Through Digitalized Comments. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Nam, K.; Koo, C. Examining Information Sharing in Social Networking Communities: Applying Theories of Social Capital and Attachment. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Social Capital Expectation and Usage of Social Media: The Moderating Role of Social Capital Susceptibility. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2017, 36, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caber, M.; Albayrak, T. Push or pull? Identifying Rock Climbing Tourists’ Motivations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.; Wong, K.K.F.; Chang, R.C.Y. Health or Self-Indulgence? the Motivations and Characteristics of Spa-Goers. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L.; McKay, S.L. Motives of Visitors Attending Festival Events. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriotis, K.; Agiomirgianakis, G. Cruise Visitors’ Experience in a Mediterranean Port of Call. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Lee, W.-H.; Chen, W.-Y. How to Catch Their Attention? Taiwanese Flashpackers Inferring Their Travel Motivation from Personal Development and Travel Experience. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 22, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.V. Motivations to Cruise: An Itinerary and Cruise Experience Study. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2011, 18, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.A.; Meyer, T.P. Functionalism and the Mass Media. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 1975, 19, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.E.; North, A.C.; Heritage, B. The Uses and Gratifications of Using Facebook Music Listening Applications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 39, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smock, A.D.; Ellison, N.B.; Lampe, C.; Wohn, D.Y. Facebook as a Toolkit: A Uses and Gratification Approach to Unbundling Feature Use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 2322–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Dhir, A.; Nieminen, M. Uses and Gratifications of digital photo sharing on Facebook. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.; Kim, Y.-G. Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Communities: An E-Business Perspective. Expert Syst. Appl. 2004, 26, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Ghose, S. An Analysis of Frequency and Duration of Search on the Internet. J. Bus. 2004, 77, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Chua, A.Y. In Search of Patterns Among Travellers’ Hotel Ratings in TripAdvisor. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Understanding the Intention to Follow the Advice Obtained in an Online Travel Community. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Mafe, C.; Bigné-Alcañiz, E.; Currás-Pérez, R. The Effect of Emotions, eWOM Quality and Online Review Sequence on Consumer Intention to Follow Advice Obtained from Digital Services. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 31, 465–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Haas, H.; Gurevitch, M. On the Use of the Mass Media for Important Things. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1973, 38, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Khalil, A.; Lonka, K.; Tsai, C.-C. Do Educational Affordances and Gratifications Drive Intensive Facebook Use Among Adolescents? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E. Mass Communication Research and the Study of Popular Culture: An Editorial Note on a Possible Future for This Research. Stud. Public Commun. 1959, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, D.L. Political Communication Research and the Uses and Gratifications Model a Critique. Commun. Res. 1979, 6, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.B. Measurement of Gratifications. Commun. Res. 1979, 6, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donohoe, S. Advertising Uses and Gratifications. Eur. J. Mark. 1994, 28, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, T.E. Uses and Gratifications Theory in the 21st Century. Mass Commun. Soc. 2000, 3, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, J.; Jin, S.V.; Kim, J. Gratifications of Using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat to Follow Brands: The Moderating Effect of Social Comparison, Trust, Tie Strength, and Network Homophily on Brand Identification, Brand Engagement, Brand Commitment, and Membership Intention. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korgaonkar, P.K.; Wolin, L.D. A Multivariate Analysis of Web Usage. J. Advert. Res. 1999, 39, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, R.; Conduit, J.; Fahy, J.; Goodman, S. Social Media Engagement Behaviour: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective. J. Strat. Mark. 2015, 24, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, W.-C.; Lin, H.-H.; Wang, Y.-S.; Shih, Y.-W.; Cheng, K.-H. Factors Affecting Users’ Continuance Intention of Mobile Social Network Service. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 39, 983–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.W.; Kim, J.; Libaque-Saenz, C.F.; Chang, Y.; Park, M.-C. Use and Gratifications of Mobile SNSs: Facebook and KakaoTalk in Korea. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.-K.; Contractor, N.S. Seniors’ Usage of Mobile Social Network Sites: Applying Theories of Innovation Diffusion and Uses and Gratifications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.-K.; Fowler, D.; Goh, B.; Yuan, J.J. Social Media Marketing: Applying the Uses and Gratifications Theory in the Hotel Industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 25, 771–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, K.; Kim, T.T.; Karatepe, O.M.; Lee, G. An Exploration of the Factors Influencing Social Media Continuance Usage and Information Sharing Intentions Among Korean Travellers. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plume, C.J.; Slade, E.L. Sharing of Sponsored Advertisements on Social Media: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-T.B.; Gebsombut, N. Communication Factors Affecting Tourist Adoption of Social Network Sites. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Parkinson, J.; Thaichon, P. Digital Content Marketing as a Catalyst for e-WOM in Food Tourism. Australas. Mark. J. (AMJ) 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eighmey, J.; Mccord, L. Adding Value in the Information Age: Uses and Gratifications of Sites on the World Wide Web. J. Bus. Res. 1998, 41, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curras-Perez, R.; Ruiz-Mafe, C.; Sanz-Blas, S. Determinants of User Behaviour and Recommendation in Social Networks. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 1477–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntinga, D.G.; Moorman, M.; Smit, E.G. Introducing COBRAs. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.E.; Sugiyama, S. Mobile Phones as Fashion Statements: The Co-creation of Mobile Communication’s Public Meaning. In Serious Games; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: London, UK, 2005; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Nysveen, H.; Pedersen, P.E.; Thorbjørnsen, H. Intentions to Use Mobile Services: Antecedents and Cross-Service Comparisons. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedlund, A.; Faghankhani, H. Platform Orchestration for Efficiency, Development, and Innovation. In Proceedings of the 2015 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2015; pp. 1380–1388. [Google Scholar]

- Quan-Haase, A.; Young, A.L. Uses and Gratifications of Social Media: A Comparison of Facebook and Instant Messaging. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2010, 30, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, A.E.; Baek, K.; Coddington, M.; Yaschur, C. Seeking and Sharing: Motivations for Linking on Twitter. Commun. Res. Rep. 2014, 31, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, G.; Haridakis, P. YouTube Users Watching and Sharing the News: A Uses and Gratifications Approach. J. Electron. Publ. 2008, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.G.; Strutton, D.; Thompson, K. Self-Enhancement as a Motivation for Sharing Online Advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2012, 12, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabash, S.; Chiang, Y.-H.; Huang, K. MAM & U&G in Taiwan: Differences in the Uses and Gratifications of Facebook as a Function of Motivational Reactivity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.; Holton, A.; Harp, D.; Yaschur, C. The Links That Bind: Uncovering Novel Motivations for Linking on Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 2243–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, K. Contextual Social Capital: Linking the Contexts of Social Media Use to Its Outcomes. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 582–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.-W.; Zmud, R.W.; Kim, Y.-G.; Lee, J.-N. Behavioral Intention Formation in Knowledge Sharing: Examining the Roles of Extrinsic Motivators, Social-Psychological Forces, and Organizational Climate. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanhalli, A.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, K.-K. Contributing Knowledge to Electronic Knowledge Repositories: An Empirical Investigation. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, M.; Rosengren, S. Receiving Word-of-Mouth From the Service Customer: An Emotion-Based Effectiveness Assessment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2007, 14, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, E.; Ruiz, C.; Andreu, L.; Hernández-Ortega, B.; Ruiz, C. The Role of Social Motivations, Ability, and Opportunity in Online Know-How Exchanges: Evidence from the Airline Services Industry. Serv. Bus. 2013, 9, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, J.-J.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Lin, B.; Ooi, K.-B. Generating Travel-Related Contents through Mobile Social Tourism: Does Privacy Paradox Persist? Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 914–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.-Y.; Heng, C.-S.; Lin, Z. Social Media Brand Community and Consumer Behavior: Quantifying the Relative Impact of User-and Marketer-Generated Content. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhong, D. Using Social Network Analysis to Explain Communication Characteristics of Travel-Related Electronic Word-of-Mouth on Social Networking Sites. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M. Anomie, Ego-enhancement and Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1977, 4, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Hagan, L.A.R. Motivation of Pleasure Travel and Tourism. Encycl. Hosp. Tour. 1993, 21, 798–810. [Google Scholar]

- Fodness, D. Measuring Tourist Motivation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Jurowski, C. Testing the Push and Pull Factors. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 844–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iso-Ahola, S.E. Toward a Social Psychological Theory of Tourism Motivation: A Rejoinder. Ann. Tour. Res. 1982, 9, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.-L.; Lee, S.; Han, H. Consequences of Cruise Line Involvement: A Comparison of First-Time and Repeat Passengers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1658–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Role of Motivations for Luxury Cruise Traveling, Satisfaction, and Involvement in Building Traveler Loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 70, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An Assessment of the Image of Mexico as a Vacation Destination and the Influence of Geographical Location Upon That Image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, T.; Mattila, A.S. The Role of Affective Factors on Perceived Cruise Vacation Value. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Petrick, J.F. Why Do You Cruise? Exploring the Motivations for Taking Cruise Holidays, and the Construction of a Cruising Motivation Scale. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, S.; Kennell, J.; Vujičić, M.D.; Jovanovic, T. Urban Tourist Motivations: Why Visit Ljubljana? Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 382–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Chua, B.-L.; Han, H. Role of Service Encounter and Physical Environment Performances, Novelty, Satisfaction, and Affective Commitment in Generating Cruise Passenger Loyalty. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, C.; Mihalic, T.A. New Frontiers in Travel Motivation and Social Media: The Case of Longyearbyen, the High Arctic. Sustainabiloity 2020, 12, 5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikari, C.; Hatzithomas, L.; Fotiadis, T.; Folinas, D. Push and Pull Travel Motivation: Segmentation of the Greek Market for Social Media Marketing in Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narangajavana, Y.; Fiol, L.J.C.; Tena, M.Á.M.; Artola, R.M.R.; García, J.S. The Influence of Social Media in Creating Expectations. an Empirical Study for a Tourist Destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 65, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Stylos, N.; Bellou, V. Destination Atmospheric Cues as Key Influencers of Tourists’ Word-of-Mouth Communication: Tourist Visitation at Two Mediterranean Capital Cities. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.X. Effects of Restaurant Satisfaction and Knowledge Sharing Motivation on eWOM Intentions: The Moderating Role of Technology Acceptance Factors. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 93–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran, J.; Olya, H.; Han, H.; Kapuscinski, G. Determinants of Canal Boat Tour Participant Behaviours: An Explanatory Mixed-Method Approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, C.; Camarero, C.; Laguna-García, M. Towards a New Approach of Destination Loyalty Drivers: Satisfaction, Visit Intensity and Tourist Motivations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 20, 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Lee, J.; Tsai, H. Travel Photos: Motivations, Image Dimensions, and Affective Qualities of Places. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Schuett, M.A. Determinants of Sharing Travel Experiences in Social Media. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanqin, Z.Q.; Lam, T. An Analysis of Mainland Chinese Visitors’ Motivations to Visit Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Uysal, M.; Kim, J.; Ahn, K. Nature-Based Tourism: Motivation and Subjective Well-Being. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, S76–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Jogaratnam, G.; Noh, J. Travel Decisions of Students at a Us University: Segmenting the International Market. J. Vacat. Mark. 2006, 12, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.G.T.; Han, H. Antecedents of Space Traveler Behavioral Intention. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G.; Reichel, A. An Exploratory Inquiry into Destination Risk Perceptions and Risk Reduction Strategies of First Time vs. Repeat Visitors to a Highly Volatile Destination. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-I. Customization, Immersion Satisfaction, and Online Gamer Loyalty. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, L. Whence Consumer Loyalty. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, L.; Hu, M.; Liu, W. Influence of Customer Engagement with Company Social Networks on Stickiness: Mediating Effect of Customer Value Creation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckert, M.; Liu, X.; Law, R. A Segmentation of Online Reviews by Language Groups: How English and Non-English Speakers Rate Hotels Differently. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 48, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C. How to Unite the Power of the Masses? Exploring Collective Stickiness Intention in Social Network Sites From the Perspective of Knowledge Sharing. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2015, 35, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorin, J.F. Mixed Methods Research: An Opportunity to Improve Our Studies and Our Research Skills. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochim, W.M. An Introduction to Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation. Eval. Program Plan. 1989, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Herrera, A.; Bigné, E.; Aldás-Manzano, J.; Curras-Perez, R. A Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility Following the Sustainable Development Paradigm. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 140, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hootsuite. The Global State of Digital in October 2019. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/us/blog/2019/10/the-global-state-of-digital-in-october-2019 (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Lohmöller, J.-B. Latent Variable Path Modeling with Partial Least Squares; Physica: Heidelberg, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Guide, V.D.R.; Ketokivi, M. Notes from the Editors: Redefining Some Methodological Criteria for the Journal. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 37, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönkkö, M.; McIntosh, C.N.; Antonakis, J.; Edwards, J.R. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Time for Some Serious Second Thoughts. J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 47, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS Path Modeling in New Technology Research: Updated Guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing Measurement Model Quality in PLS-SEM Using Confirmatory Composite Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis with Small Samples Using Partial Least Squares. Stat. Strateg. Small Sample Res. 1999, 1, 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A Partial Least Squares Latent Variable Modeling Approach for Measuring Interaction Effects: Results from a Monte Carlo Simulation Study and an Electronic-Mail Emotion/Adoption Study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Cha, F.J. Partial Least Squares. Adv. Methods Mark. Res. 1994, 407, 52–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015; Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 12 January 2019).

- Papacharissi, Z.; Mendelson, A. 12 Toward a New(er) Sociability: Uses, Gratifications and Social Capital on Facebook. In Media Perspectives for the 21st Century; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2011; pp. 212–230. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbaugh, E.E. Motives for Maintaining Personal Journal Blogs. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.C.-C. Online Stickiness: Its Antecedents and Effect on Purchasing Intention. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2007, 26, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oum, S.; Han, D. An Empirical Study of the Determinants of the Intention to Participate in User-Created Contents (UCC) Services. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 15110–15121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.Y.; Luo, C.; Sia, C.L.; Chen, H. Credibility of Electronic Word-of-Mouth: Informational and Normative Determinants of On-line Consumer Recommendations. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2009, 13, 9–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, J.D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common Beliefs and Reality About PLS. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van House, N.; Davis, M.; Ames, M.; Finn, M.; Viswanathan, V. The Uses of Personal Networked Digital Imaging. In Proceedings of the Communication CHI ’05 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Portland, OR, USA, 2–7 April 2005; pp. 1853–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W.-L.; Lee, Y.-J.; Huang, P.-H. Creative Experiences, Memorability and Revisit Intention in Creative Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 19, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.; Styven, M.E.; Ayeh, J.K. Using Facebook for Travel Decision-Making: An International Study of Antecedents. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1021–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Ju, T.L.; Yen, C.-H.; Chang, C.-M. Knowledge Sharing Behavior in Virtual Communities: The Relationship Between Trust, Self-Efficacy, and Outcome Expectations. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-T.; Wang, Y.-S.; Liu, E.-R. The Stickiness Intention of Group-Buying Websites: The Integration of the Commitment–Trust Theory and E-Commerce Success Model. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Min, Q.; Han, S.; Liu, Z. Understanding Followers’ Stickiness to Digital Influencers: The Effect of Psychological Responses. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Antecedents of Consumer Intention to Follow and Recommend an Instagram Account. Online Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 1046–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.; Lee, C.-K.; Lee, Y.-K.; Reisinger, Y. What Are the Triggers of Asian Visitor Satisfaction and Loyalty in the Korean Heritage Site? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, E.; Andreu, L.; Pérez-Cabañero, C.; Ruiz, C. Brand Love Is All Around: Loyalty Behaviour, Active and Passive Social Media Users. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 1613–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Araujo, B.; Tam, C. Why Do People Share Their Travel Experiences on Social Media? Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Context | Author | Gratifications | Sample | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of mobile social media for travelling | [33] | Informativeness Social interactivity Playfulness | 500 senior Korean travellers, mobile SNS users Online survey | Informativeness, social interactivity and playfulness influence consumers’ attachment to mobile social media for travelling. |

| Hotel Facebook fanpages | [34] | Information Convenience Self-expression Social interaction Entertainment | 357 users of hotel Facebook fanpages. Online survey | Information, convenience, and self-expression drive user satisfaction with the hotel’s Facebook page |

| Use of social media for travelling | [35] | Information seeking Entertainment Relationship maintenance | 450 Korean travellers, social media users. Online survey | Information seeking, entertainment, and relationship maintenance motives trigger travellers’ propensity to display higher social media continuance usage and information sharing intentions. |

| Tourism-related sponsored advertisements on Facebook | [36] | Altruism Entertainment Socialising Information seeking Information sharing Self-expression | 487 UK Facebook users Online and face-to-face survey | Altruism, entertainment, socialising, and information seeking are positive drivers of intention to share tourism-related sponsored advertisements on Facebook |

| Use of social media for travelling | [37] | Information-seeking Entertainment Relationship maintenance | 475 Thai tourists Online survey | Information-seeking, entertainment relationship maintenance and Internet self-efficacy positively influence the intention to use SNSs for trips. |

| Food-related content on social media | [38] | Content information Content entertainment Social interaction Self-expression | 707 Chinese food tourists Online survey | Positive associations between content entertainment and Informational Social Impact (ISI), and between self-expression and Normative Social Impact (NSI). Content information and social interaction had a positive relationship with both NSI and ISI. |

| Characteristic | % (n = 401) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 56 |

| Women | 44 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 20 |

| 26–35 | 34 | |

| 36–45 | 26 | |

| 46–55 | 13 | |

| >55 | 7 | |

| Educational level | Secondary | 9 |

| Undergraduate | 58 | |

| Postgraduate | 33 | |

| Occupation | Student | 24 |

| Self-employed | 16 | |

| Employed | 44 | |

| Unemployed | 5 | |

| Retired | 5 | |

| Others | 6 | |

| How often have you interacted with social media for tourism purposes in the last three months? | Daily | 64 |

| Once a week | 16 | |

| Twice a month | 12 | |

| Less than once a month | 8 | |

| How often have you read posts with travel-related information on social media in the last three months? | Daily | 75 |

| Once a week | 15 | |

| Twice a month | 7 | |

| Less than once a month | 3 | |

| When was the last time you posted travel-related information on social media? | <1 year ago | 89 |

| >1 year ago | 9 | |

| Never | 2 |

| Source | Variable | Item | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uses and Gratifications of social media | Expressive information sharing | EIS1 | To provide information. | 4.67 | 1.95 |

| EIS2 | To present information about my special interests. | 4.60 | 2.02 | ||

| EIS3 | To share information that may be of use or interest to others. | 5.23 | 1.77 | ||

| Entertainment | ENT1 | Because I like it. | 5.26 | 1.79 | |

| ENT2 | Because I just like to play around on social media. | 4.52 | 1.98 | ||

| ENT3 | When I have nothing better to do. | 3.86 | 2.00 | ||

| ENT4 | Because it passes the time, particularly when I am bored. | 4.64 | 1.94 | ||

| Social enhancement | SOC1 | To attract attention. | 2.64 | 1.79 | |

| SOC2 | Because my posts make me seem cool to my peers. | 2.45 | 1.74 | ||

| SOC3 | Because I like when people read things about me. | 2.92 | 1.83 | ||

| Leisure travel motivation | LEI1 | To seek adventure | 5.19 | 1.67 | |

| LEI2 | To seek diversion and entertainment | 5.24 | 1.63 | ||

| LEI3 | To live exciting experiences | 5.28 | 1.70 | ||

| Relaxation travel motivation | REL1 | To rest/to relax | 4.99 | 1.86 | |

| REL2 | To alleviate stress | 4.90 | 1.98 | ||

| REL3 | To escape | 5.13 | 1.95 | ||

| Learning/discover travel motivation | LEA1 | To discover new places | 5.74 | 1.57 | |

| LEA2 | To explore historical and cultural heritage | 5.62 | 1.56 | ||

| LEA3 | To learn about other cultures and ways of life | 5.70 | 1.53 | ||

| LEA4 | To enrich myself intellectually | 5.51 | 1.67 | ||

| Social-bonding travel motivation | BON1 | To meet new people | 4.97 | 1.94 | |

| BON2 | To integrate myself into the life and activities of local people | 4.61 | 1.98 | ||

| BON3 | To communicate with my friends | 4.94 | 1.91 | ||

| Stickiness | STICK1 | I could spend a long time on social media sites reviewing travel-related information. | 4.25 | 1.84 | |

| STICK2 | I intend to prolong my stays on social media sites to review travel-related information every time I am online | 4.35 | 1.87 | ||

| STICK3 | I would like to review travel-related information on social media sites more often | 4.19 | 1.85 | ||

| Continuance intention to create UGC | UGC1 | I intend to create more travel-related content and share it with others on social media sites if possible | 3.63 | 1.98 | |

| UGC2 | I intend to post more travel-related information on social media sites | 3.52 | 1.97 | ||

| UGC3 | I intend to spend more time viewing travel-related posts on social media sites | 3.80 | 1.93 | ||

| UGC4 | I intend to participate more on social media sites in the future, especially on travel-related matters | 3.79 | 1.93 | ||

| eWOM review adoption | eWOM1 | Information from online reviews contributed to my knowledge of the tourism destination | 5.18 | 1.63 | |

| eWOM2 | Information from online reviews helped me to make the decision to visit the tourism destination | 5.14 | 1.67 | ||

| eWOM3 | Information from online reviews enhanced my effectiveness in making the decision to visit the tourism destination | 5.16 | 1.64 | ||

| eWOM4 | Information from online reviews motivated me to visit the tourism destination | 5.08 | 1.64 | ||

| Construct | Item | Convergent Validity | Reliability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loads | t-Value | Loading Average | Cronbach’s α | Composite Reliability | AVE | |||

| Stickiness | STICK1 | 0.90 | 74.30 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.82 | |

| STICK2 | 0.92 | 89.76 | ||||||

| STICK3 | 0.89 | 60.23 | ||||||

| Continuance intention to create UGC | UGC1 | 0.90 | 79.29 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.79 | |

| UGC 2 | 0.92 | 85.96 | ||||||

| UGC 3 | 0.86 | 45.24 | ||||||

| UGC 4 | 0.86 | 50.57 | ||||||

| eWOM review adoption | eWOM1 | 0.89 | 52.29 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.85 | |

| eWOM2 | 0.93 | 92.14 | ||||||

| eWOM3 | 0.94 | 96.55 | ||||||

| eWOM4 | 0.94 | 74.76 | ||||||

| Social media gratifications | Information sharing | EIS1 | 0.92 | 90.18 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.81 |

| EIS2 | 0.91 | 84.00 | ||||||

| EIS3 | 0.86 | 41.39 | ||||||

| Entertainment | ENT1 | 0.81 | 40.49 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 090 | 0.69 | |

| ENT2 | 0.87 | 48.48 | ||||||

| ENT3 | 0.84 | 51.24 | ||||||

| ENT4 | 0.81 | 33.51 | ||||||

| Social-enhancement | SOC1 | 0.89 | 59.89 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.80 | |

| SOC2 | 0.89 | 59.73 | ||||||

| SOC3 | 0.90 | 64.23 | ||||||

| Social media gratifications (2° order) | EIS | 0.48 | 22.82 | - | - | - | - | |

| ENT | 0.45 | 25.41 | ||||||

| SOC | 0.32 | 16.08 | ||||||

| Leisure | LEI1 | 0.94 | 97.22 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.91 | |

| LEI2 | 0.95 | 149.36 | ||||||

| LEI3 | 0.96 | 162.77 | ||||||

| Relaxation | REL1 | 0.93 | 99.36 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.90 | |

| REL2 | 0.96 | 158.18 | ||||||

| REL3 | 0.94 | 107.40 | ||||||

| Learning/Discover | LEA1 | 0.91 | 77.10 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.84 | |

| LEA2 | 0.93 | 79.98 | ||||||

| LEA3 | 0.93 | 74.85 | ||||||

| LEA4 | 0.90 | 63.46 | ||||||

| Social bonding | BON1 | 0.92 | 85.07 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.83 | |

| BON2 | 0.93 | 85.68 | ||||||

| BON3 | 0.89 | 61.50 | ||||||

| GRAT | LEI | REL | LEA | BON | STICK | UGC | eWOM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gratifications | 0.69 | |||||||

| Leisure | 0.59 | 0.95 | ||||||

| Relaxation | 0.53 | 0.72 | 0.95 | |||||

| Learning/discover | 0.54 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.92 | ||||

| Social bonding | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.91 | |||

| Stickiness | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.90 | ||

| UGC | 0.64 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.77 | 0.89 | |

| eWOM review adoption | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.92 |

| GRAT | LEI | REL | LEA | BON | STICK | UGC | eWOM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gratifications | ||||||||

| Leisure | 0.62 | |||||||

| Relaxation | 0.58 | 0.76 | ||||||

| Learning/discover | 0.57 | 0.75 | 0.73 | |||||

| Social bonding | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.73 | ||||

| Stickiness | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.65 | 0.75 | |||

| UGC | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.68 | ||

| eWOM review adoption | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.53 |

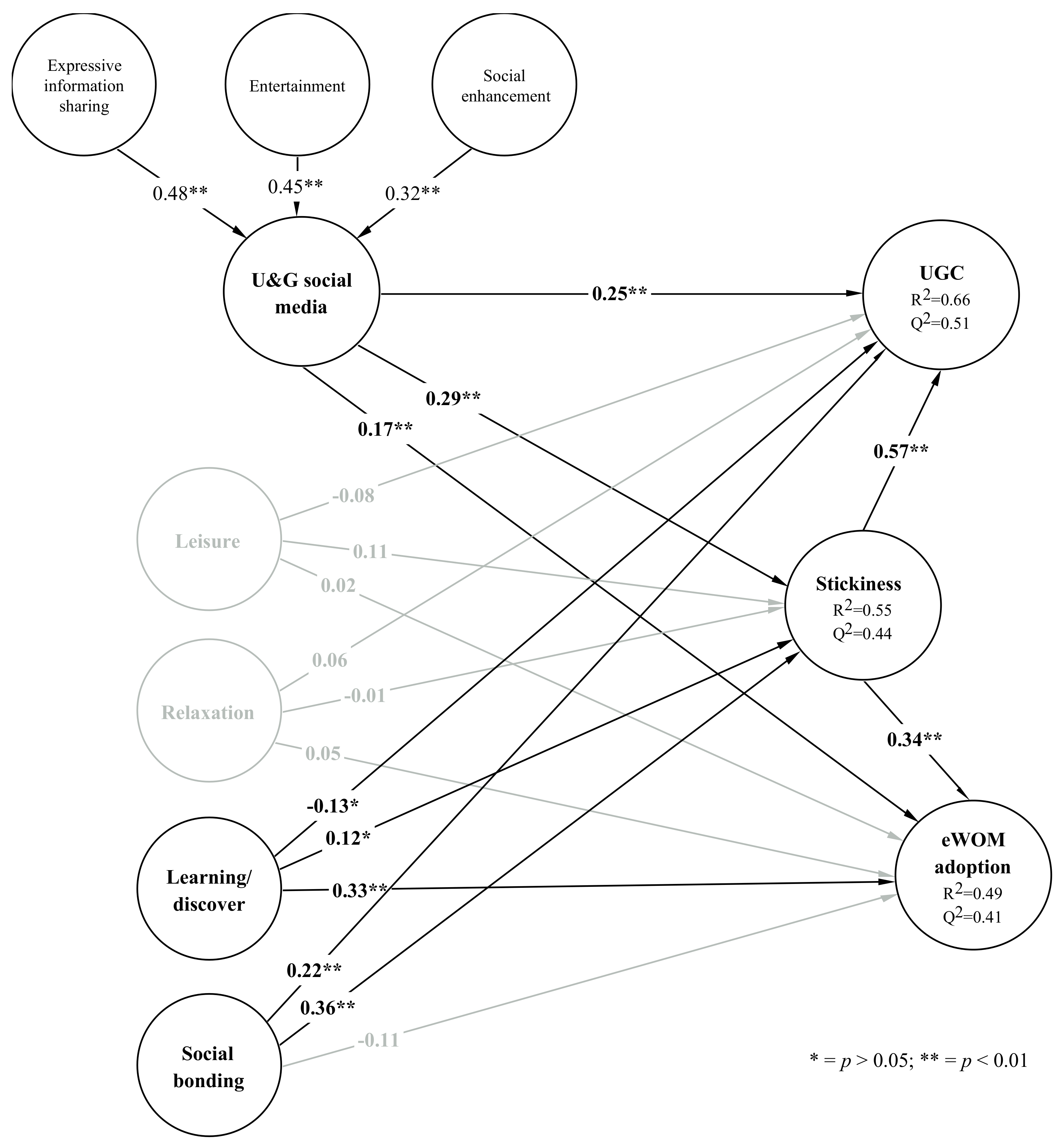

| Hypothesis | Structural Relationship | β | t-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | U&G of social media → Stickiness | 0.29 | 5.93 ** | Accepted |

| H2 | U&G of social media → UGC | 0.25 | 5.48 ** | Accepted |

| H3 | U&G of social media → eWOM review adoption | 0.17 | 2.75 ** | Accepted |

| H4a | Leisure → Stickiness | 0.11 | 1.51 | Not accepted |

| H4b | Relaxation → Stickiness | −0.01 | 0.11 | Not accepted |

| H4c | Learning/discover → Stickiness | 0.12 | 2.11 * | Accepted |

| H4d | Social bonding → Stickiness | 0.36 | 6.21 ** | Accepted |

| H5a | Leisure → UGC | −0.08 | 1.48 | Not accepted |

| H5b | Relaxation → UGC | 0.06 | 1.07 | Not accepted |

| H5c | Learning/discover → UGC | −0.13 | 2.46 * | Not accepted |

| H5d | Social bonding → UGC | 0.22 | 4.45 ** | Accepted |

| H6a | Leisure → eWOM review adoption | 0.02 | 0.21 | Not accepted |

| H6b | Relaxation → eWOM review adoption | 0.05 | 0.69 | Not accepted |

| H6c | Learning/discover → eWOM review adoption | 0.33 | 4.39 ** | Accepted |

| H6d | Social bonding → eWOM review adoption | −0.11 | 1.69 | Not accepted |

| H7 | Stickiness → UGC | 0.57 | 11.96 ** | Accepted |

| H8 | Stickiness → eWOM review adoption | 0.34 | 5.15 ** | Accepted |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chavez, L.; Ruiz, C.; Curras, R.; Hernandez, B. The Role of Travel Motivations and Social Media Use in Consumer Interactive Behaviour: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218789

Chavez L, Ruiz C, Curras R, Hernandez B. The Role of Travel Motivations and Social Media Use in Consumer Interactive Behaviour: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective. Sustainability. 2020; 12(21):8789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218789

Chicago/Turabian StyleChavez, Luciana, Carla Ruiz, Rafael Curras, and Blanca Hernandez. 2020. "The Role of Travel Motivations and Social Media Use in Consumer Interactive Behaviour: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective" Sustainability 12, no. 21: 8789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218789

APA StyleChavez, L., Ruiz, C., Curras, R., & Hernandez, B. (2020). The Role of Travel Motivations and Social Media Use in Consumer Interactive Behaviour: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective. Sustainability, 12(21), 8789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218789