Employee Volunteerism—Conceptual Study and the Current Situation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Hypotheses and Research Question

3.1. Personal Characteristics

3.2. Formal Volunteerism

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

5.1. Secondary Findings

5.2. Empirical Study

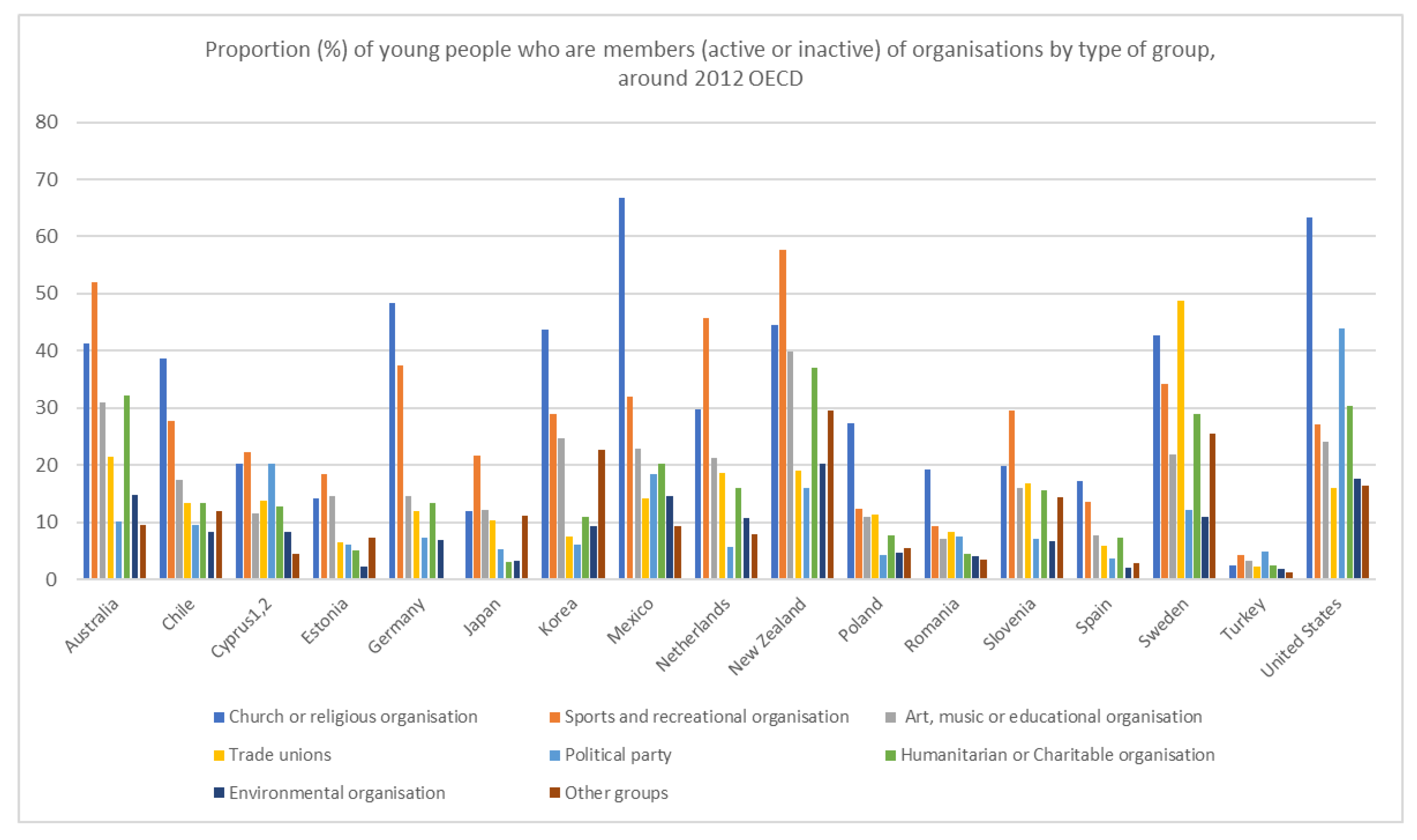

5.2.1. On the Individual Level

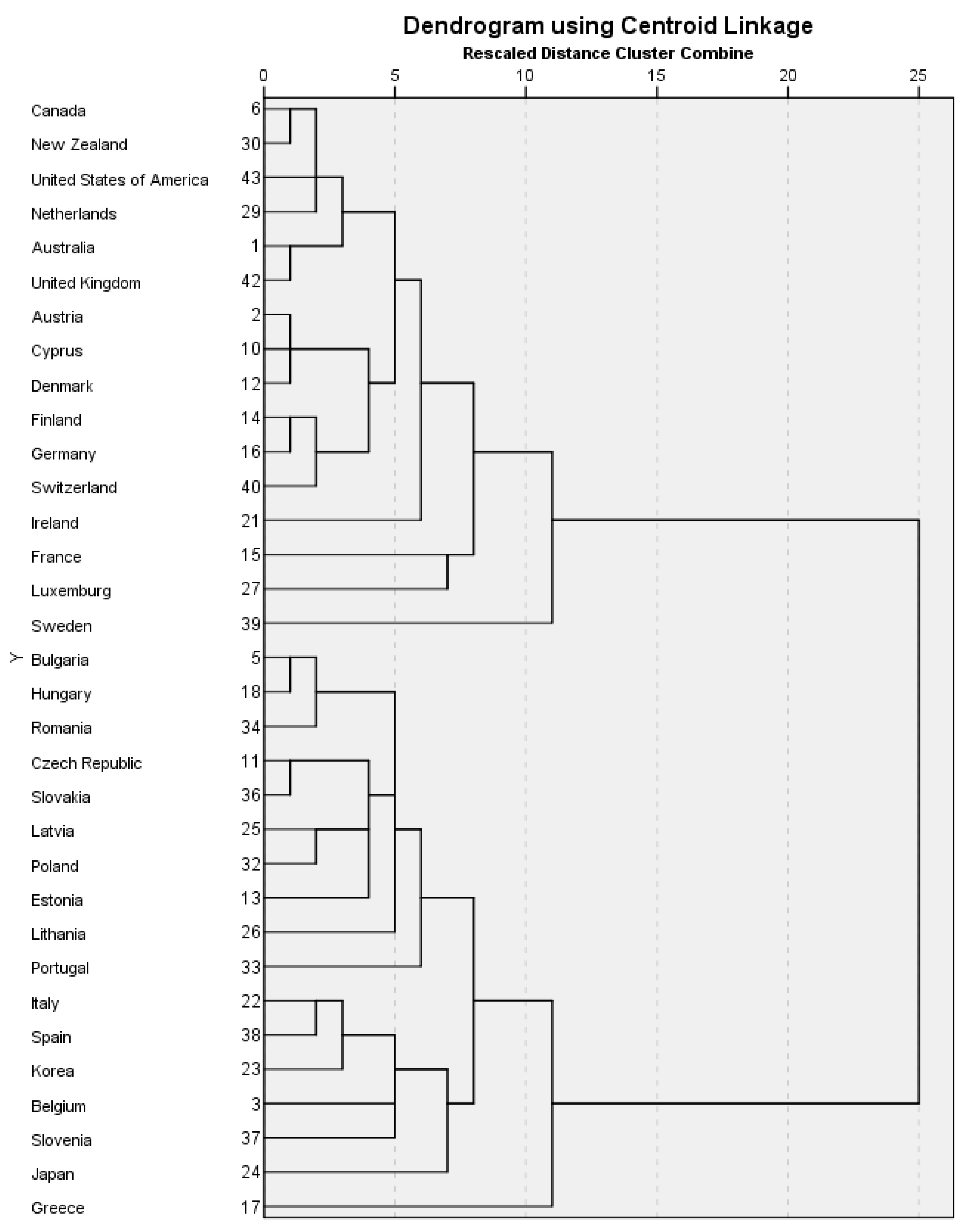

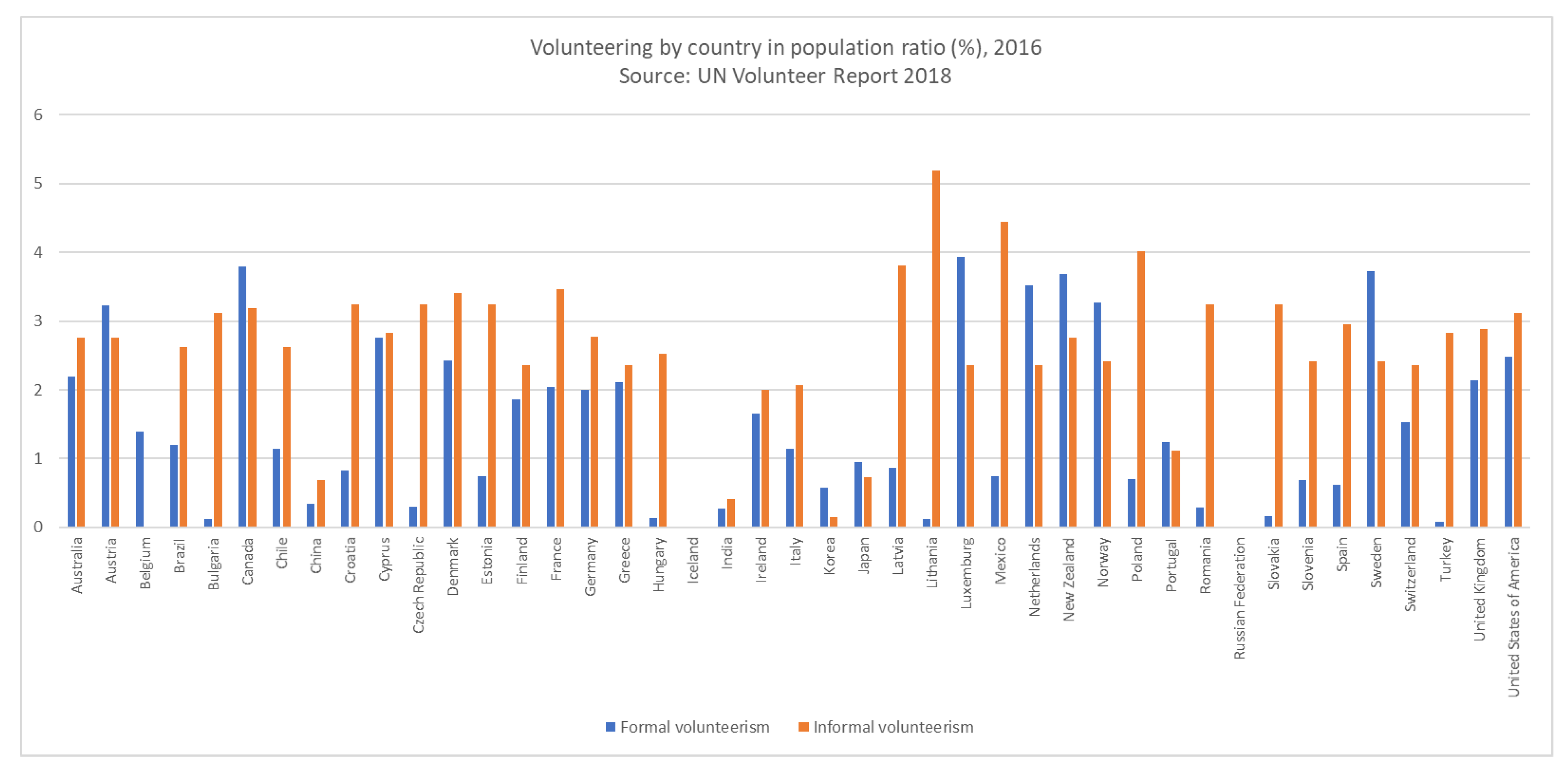

5.2.2. On the Regional Level

6. Conclusions and Limitation

Limitations

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Statistical Data Sources

| Database Name | Indices | Definition | Sample Size and Characteristics | Year | Institute | Source |

| COVID 19 data | ||||||

| CAF Reports | Various | The Voice of Charities Facing COVID-19 Worldwide | The philanthropic sector from 99 countries Vol1 122 countries n = 544 Vol2 n = 880 Vol3 125 countries n = 414 | 2020. Vol 1. 03 Vol 2. 04 Vol3 05. | CAF | https://www.cafonline.org/about-us/research/coronavirus-and-charitable-giving |

| Interactive COVID-19 Data by Location | Reported data for cases, deaths and testing with data explorer (different time series). Government responses (various indices) we were working with Workplace closures: Stay-at-home restrictions, Internal movement restriction, International travel restriction, Testing policy, Contact tracing, Government Stringency Index. | Using the same data from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and governmental responses have also been tracked by Oxford University, by the Blavatnik School of Government. | Worldwide or Selected regions | 2020. updated daily | International SOS | https://pandemic.internationalsos.com/2019-ncov/covid-19-data-visualisation |

| Savana Coronavirus data tracking | The tracker covers 5 key areas: concern & impact, home & work,out-of-home & retail, news sources and approval ratings. Here we focused on work. | Tracking the variety of new working situations that UK adults find themselves in, including those who have been furloughed. | Daily tracker, with 1000+ UK respondents every day | Daily report | Savanta | https://savanta.com/coronavirus-data-tracker/ |

| Personal level | ||||||

| World Values Survey Wave 6. | Selected questions from the survey (4 scales Likert and multiply choices) | Memberships (Inactive/Active) of various voluntary organizations Personal values and opinions about voluntary organizations | World wide (over 60 countries) n = 89,565 | 2010–2014 | World Values Survey | https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp |

| World Values Survey Wave 7., EVS WVS Cross-National Wave 7 joint core | Selected questions from the survey (focusing on values) | World wide (48 countries/territories) | 2017–2020 | World Values Survey and European Values Study | http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp | |

| Macroeconomical level | ||||||

| OECD1. OECD calculations based on data from the European Values Survey (2011), European Values Study 2008, Integrated Dataset (EVS 2008), and the World Values Survey Association (2009), World Values Survey, Wave 5 2005–2008, Official Aggregate v.20140429, | Distribution of volunteers by field of activity Percentage of volunteers, 2008 or latest available year | Selected from Better Life Initiative: Measuring Well-Being and Progress | Worldwide selected from various databases | 2016–2018 | OECD | https://www.oecd.org/statistics/better-life-initiative.htm |

| OECD2. OECD calculations based on data from OECD (2012), OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC database) | Frequency of formal volunteering in months, 2012 | 2012 | ||||

| Source: OECD calculations based on the Harmonized European Time Use Survey web application, Eurostat Time Use database, survey micro-data; and tabulations from national statistical offices. | Time spent in formal, 2013 or latest available year Average minutes of volunteering per day, by all respondents and by volunteers only, among people aged 15–64 | 2013 and latest | ||||

| European Social Survey 2012. | Proportion of people involved in work for voluntary or charitable organizations in the past year | European Social Survey (ESS) 2012, which asks respondents whether, over the last 12 months, they have been involved in work for voluntary or charitable organizations | 28 country, in each with at least n = 2000 | 2012 | ESS | https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/download.html?r=6 |

| Gallup World Poll Citizen Engagement Index | Proportion of people who volunteered time to an organization in the past month, | “Have you done any of the following in the past month? How about volunteered your time to an organization?” In other words, data from Gallup World Poll reflect the proportion of people engaging in any kind of voluntary work roughly around the time of the survey. | around 160 countries each with n = 1000 | 2015 or last year available1 | Gallup | https://www.gallup.com/analytics/232838/world-poll.aspx |

| World Happiness Report | Volunteering is defined as helping another person with no expectation of monetary compensation. Percentage of respondents within the country who reported Donating Money/Time to a Charity in the Past Month. | Database presents the percentage of respondents reporting that they donated money to charity or volunteered time to an organization within the past month within each country surveyed by the Gallup World Poll, | Based on Gallup World Poll | averaged across 2009–2017. | https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2019/happiness-and-prosocial-behavior-an-evaluation-of-the-evidence/ | |

| CAF World Giving Index | Helping Percentage | The survey asks questions on many different aspects of life today including giving behaviour: Helping a stranger, Donating money, Volunteering time | the report is primarily based upon data from Gallup’s World View World Poll | 2018 | Charities Aid Foundation | http://knoema.com/WDGIVIND2018/world-giving-index |

| ILO Unpaid Work - Volunteer work. | Number of volunteers by type of volunteer work (thousands) Volunteer rate by type of volunteer work (%) -- Annual 1. Direct volunteer work, which is done to help other people directly (e.g., a neighbour, a friend, a stranger, nature); 2. Organization-based volunteer work, which is done through or for an organization, community or group. | According to the latest international standards (see 19th ICLS, Resolution I), “volunteers” includes any person of working age who engages in unpaid, non-compulsory work for others, for at least one hour in a four week or one month reference period. Unpaid means that volunteers do not receive a remuneration in cash or in kind for the work done or hours worked. Nevertheless, volunteers may receive some small form of support or stipend in cash or in kind usually meant to enable their participation. | ILOSTAT database is collected from official national reports or produced using published micro-data by national statistical offices. | 2016 or latest | ILO | https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/volunteer-work/ |

| The Index of Philanthropic Freedom | ranking based on expert opinion survey 63 experts representing 64 different countries | To compute the overall score, and by extension the overall rankings, CGP staff had to first compute the scores of the three indicators based on an expert survey. | 64 countries in the study were selected to represent all regions of the world as equally as possible | 2015 | Hudson Institute | https://www.hudson.org/research/11259-the-interactive-map-of-philanthropic-freedom |

| UNV Volunteering by country | Formal and informal volunteering (full-time equivalent) | FORMAL VOLUNTEERING Voluntary activity is undertaken through an organization, typified by volunteers making an ongoing or sustained commitment to an organization and contributing their time on a regular basis (UNV 2015a, p. xxv). INFORMAL VOLUNTEERING Voluntary activities have done directly, unmediated by any formal organization that coordinates larger-scale volunteer efforts (UNV 2015a, p. xxv). | 62 countries | 2018 | UN Volunteers | https://www.unv.org/sites/default/files/UNV_SWVR_2018_English_WEB.pdf |

Appendix B. Empirical Findings

| Organization | Index | Cluster 1. | Cluster 2. | Cluster 3. | Total | Eta | ANOVA (df = 2) | |||||||||||||||

| Mean | N | Std. Deviation | Median | Mean | N | Std. Deviation | Median | Mean | N | Std. Deviation | Median | Mean | N | Std. Deviation | Median | Eta | Sum of Squares | F | Sig. | |||

| OECD | Fields of volunteering (Distribution of volunteers by field of activity %) | Social and health services | 28.54 | 12 | 6.85 | 29.44 | 26.39 | 13 | 8.39 | 26.47 | 30.60 | 7 | 11.99 | 26.94 | 28.12 | 32 | 8.63 | 26.89 | 0.19 | 84.02 | 0.55 | 0.58 |

| Education and culture | 27.72 | 12 | 5.09 | 27.84 | 30.23 | 13 | 5.27 | 28.30 | 29.60 | 7 | 10.02 | 33.21 | 29.15 | 32 | 6.38 | 28.58 | 0.18 | 41.18 | 0.49 | 0.62 | ||

| Social movements | 10.56 | 12 | 3.83 | 9.65 | 13.02 | 13 | 3.52 | 12.60 | 9.71 | 7 | 2.64 | 8.93 | 11.38 | 32 | 3.66 | 10.71 | 0.39 | 62.64 | 2.58 | 0.09 | ||

| Sports | 22.01 | 12 | 6.57 | 23.72 | 18.63 | 13 | 4.48 | 16.96 | 21.93 | 7 | 9.43 | 20.98 | 20.62 | 32 | 6.56 | 19.83 | 0.26 | 86.98 | 1.01 | 0.38 | ||

| Others | 11.17 | 12 | 5.12 | 10.02 | 11.73 | 13 | 5.42 | 11.53 | 8.16 | 7 | 7.52 | 5.18 | 10.74 | 32 | 5.80 | 9.81 | 0.24 | 61.65 | 0.91 | 0.41 | ||

| OECD | Participation rates in formal volunteering (Percentage) | 39.50 | 12 | 8.05 | 39.07 | 24.65 | 9 | 6.23 | 23.37 | 38.36 | 3 | 19.12 | 38.62 | 33.79 | 24 | 11.34 | 34.48 | 0.64 | 1204.89 | 7.21 | 0.00 | |

| OECD3 | Frequency of formal volunteering (Percentage of formal volunteers, by frequency) | Less than once a month | 44.14 | 12 | 5.94 | 46.23 | 53.86 | 9 | 10.53 | 55.20 | 54.41 | 3 | 7.83 | 51.01 | 49.07 | 24 | 9.28 | 47.40 | 0.54 | 583.32 | 4.38 | 0.03 |

| Less than once a week but at least once a month | 24.79 | 12 | 2.45 | 24.95 | 23.23 | 9 | 3.06 | 22.89 | 21.53 | 3 | 3.63 | 21.54 | 23.80 | 24 | 2.93 | 23.34 | 0.39 | 30.22 | 1.90 | 0.17 | ||

| At least once a week but not every day | 26.04 | 12 | 4.53 | 25.90 | 17.86 | 9 | 7.26 | 13.98 | 19.12 | 3 | 6.35 | 20.68 | 22.11 | 24 | 6.93 | 24.26 | 0.58 | 374.91 | 5.40 | 0.01 | ||

| Every day | 5.02 | 12 | 1.16 | 4.75 | 5.05 | 9 | 3.13 | 5.26 | 4.93 | 3 | 1.72 | 5.05 | 5.02 | 24 | 2.08 | 4.97 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| EUSS | Average minutes of volunteering per day | Volunteers | 131.85 | 13 | 21.16 | 130.00 | 145.60 | 10 | 31.54 | 151.00 | 75.50 | 2 | 54.45 | 75.50 | 132.84 | 25 | 32.60 | 131.00 | 0.57 | 8216.77 | 5.23 | 0.01 |

| All respondents | 5.85 | 13 | 3.44 | 4.00 | 1.90 | 10 | 1.45 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 2 | 0.71 | 1.50 | 3.92 | 25 | 3.30 | 3.00 | 0.62 | 100.75 | 6.88 | 0.00 | ||

| Proportion of people involved in work for organizations | 15–29 years old | 46.87 | 10 | 9.77 | 50.55 | 32.00 | 12 | 9.92 | 32.05 | 49.90 | 1 | 49.90 | 39.24 | 23 | 12.18 | 41.80 | 0.64 | 1324.82 | 6.83 | 0.01 | ||

| 30–49 years old | 47.96 | 10 | 8.56 | 47.40 | 32.40 | 12 | 11.46 | 28.30 | 55.20 | 1 | 55.20 | 40.16 | 23 | 12.90 | 42.70 | 0.65 | 1557.21 | 7.40 | 0.00 | |||

| GALLUP | Proportion of people who volunteered time to an organization in the past month | Total (All ages) | 32.06 | 16 | 8.57 | 31.00 | 14.88 | 17 | 8.36 | 13.00 | 16.00 | 5 | 8.66 | 16.00 | 22.26 | 38 | 11.83 | 22.00 | 0.72 | 2658.67 | 18.46 | 0.00 |

| Men | 30.94 | 16 | 8.47 | 29.00 | 15.29 | 17 | 9.55 | 13.00 | 16.00 | 5 | 8.80 | 14.00 | 21.97 | 38 | 11.70 | 22.00 | 0.66 | 2222.51 | 13.67 | 0.00 | ||

| Women | 33.19 | 16 | 8.92 | 34.00 | 14.47 | 17 | 7.61 | 13.00 | 16.20 | 5 | 8.98 | 15.00 | 22.58 | 38 | 12.26 | 23.00 | 0.75 | 3121.79 | 22.36 | 0.00 | ||

| 15–29 year olds | 27.31 | 16 | 10.82 | 27.00 | 16.24 | 17 | 10.57 | 14.00 | 12.20 | 5 | 10.78 | 12.00 | 20.37 | 38 | 12.09 | 19.50 | 0.51 | 1395.55 | 6.09 | 0.01 | ||

| Happiness | The percentage of respondents within each country within the last month | Donating Money to a Charity | 0.57 | 16 | 0.12 | 0.59 | 0.26 | 14 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 9 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.40 | 39 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 0.74 | 0.81 | 21.68 | 0.00 |

| Volunteering Time to an Organization | 0.31 | 16 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 14 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 9 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 39 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.67 | 0.20 | 14.80 | 0.00 | ||

| Giving Index | Helping a stranger | Percentage (%) | 54.94 | 16 | 9.38 | 53.00 | 38.35 | 17 | 6.79 | 37.00 | 36.50 | 4 | 6.56 | 34.50 | 45.32 | 37 | 11.55 | 44.00 | 0.74 | 2616.29 | 20.35 | 0.00 |

| Donating money | Percentage (%) | 56.44 | 16 | 12.07 | 57.00 | 24.59 | 17 | 8.99 | 23.00 | 17.25 | 4 | 6.70 | 17.00 | 37.57 | 37 | 19.60 | 34.00 | 0.86 | 10,212.28 | 48.05 | 0.00 | |

| Volunteering time | Percentage Score(%) | 30.63 | 16 | 7.65 | 29.50 | 14.71 | 17 | 7.10 | 14.00 | 13.75 | 4 | 6.08 | 15.50 | 21.49 | 37 | 10.74 | 20.00 | 0.75 | 2357.21 | 22.31 | 0.00 | |

| ILO | Number of volunteers by type of volunteer work (thousands) | Organization-based | 5282.81 | 14 | 6275.73 | 2442.70 | 1352.91 | 15 | 1744.00 | 530.20 | 692.13 | 4 | 881.01 | 341.40 | 2940.04 | 33 | 4649.43 | 1072.50 | 0.44 | 134,837,181.05 | 3.63 | 0.04 |

| Direct | 6192.66 | 13 | 7016.19 | 2271.20 | 2488.25 | 15 | 4110.53 | 950.20 | 1268.70 | 4 | 1294.37 | 900.90 | 3840.72 | 32 | 5559.38 | 1413.90 | 0.36 | 125,810,086.29 | 2.19 | 0.13 | ||

| Total | 14,879.90 | 5 | 26,798.72 | 3059.30 | 4588.38 | 4 | 2762.18 | 4596.10 | 3312.77 | 3 | 3444.29 | 1527.30 | 8557.61 | 12 | 17,227.62 | 2863.75 | 0.33 | 345,401,204.94 | 0.53 | 0.60 | ||

| Volunteer rate by type of volunteer work (%) | Organization-based | 27.09 | 14 | 10.40 | 28.45 | 11.50 | 15 | 7.17 | 10.70 | 22.70 | 4 | 21.70 | 21.25 | 19.47 | 33 | 12.93 | 16.40 | 0.58 | 1808.06 | 7.66 | 0.00 | |

| Direct | 35.74 | 13 | 25.26 | 30.30 | 21.01 | 15 | 16.03 | 16.60 | 39.38 | 4 | 35.80 | 41.00 | 29.29 | 32 | 23.47 | 22.05 | 0.34 | 1976.61 | 1.90 | 0.17 | ||

| Total | 36.95 | 2 | 17.04 | 36.95 | 16.10 | 1 | 16.10 | 2.75 | 2 | 2.19 | 2.75 | 19.10 | 5 | 19.21 | 16.10 | 0.89 | 1180.89 | 4.00 | 0.20 | |||

| Hudson | Overall Score | 4.46 | 12 | 0.22 | 4.47 | 4.14 | 7 | 0.29 | 4.21 | 3.30 | 7 | 0.46 | 3.18 | 4.06 | 26 | 0.57 | 4.23 | 0.85 | 6.00 | 30.64 | 0.00 | |

| CSO Score | 4.76 | 12 | 0.22 | 4.75 | 4.41 | 7 | 0.29 | 4.50 | 3.47 | 7 | 0.94 | 3.53 | 4.32 | 26 | 0.74 | 4.58 | 0.73 | 7.43 | 13.37 | 0.00 | ||

| Tax Score | 4.32 | 12 | 0.48 | 4.30 | 3.86 | 7 | 0.50 | 4.00 | 3.24 | 7 | 0.57 | 3.10 | 3.90 | 26 | 0.67 | 4.00 | 0.68 | 5.23 | 10.17 | 0.00 | ||

| Cross Border Score | 4.31 | 12 | 0.42 | 4.23 | 4.15 | 7 | 0.37 | 4.30 | 3.21 | 7 | 0.55 | 3.50 | 3.97 | 26 | 0.64 | 4.00 | 0.74 | 5.71 | 14.18 | 0.00 | ||

| UNV | Population aged 15 or older (million) | 32.97 | 16 | 61.96 | 7.25 | 20.88 | 17 | 28.12 | 8.94 | 268.87 | 8 | 441.88 | 51.17 | 73.99 | 41 | 213.06 | 9.25 | 0.46 | 378,700.49 | 5.01 | 0.01 | |

| Formal volunteering (person) | 806,623.50 | 16 | 1,522,462.99 | 251,905.00 | 172,321.82 | 17 | 273,249.02 | 49,417.00 | 966,845.00 | 8 | 1,397,819.71 | 349,956.00 | 574,883.10 | 41 | 1,167,086.32 | 138,769.00 | 0.30 | 4,843,275,738,619.14 | 1.85 | 0.17 | ||

| Informal volunteering (person) | 992,019.31 | 16 | 1,930,224.26 | 187,862.50 | 393,925.19 | 16 | 427,965.53 | 200,208.00 | 2,302,035.00 | 8 | 2,649,893.09 | 1,399,274.50 | 1,014,784.80 | 40 | 1,806,109.29 | 213,028.50 | 0.39 | 19,431,863,432,876.50 | 3.34 | 0.05 | ||

| Total volunteering (person) | 1,798,642.69 | 16 | 3,448,132.43 | 439,767.00 | 568,892.13 | 16 | 633,259.90 | 266,192.50 | 3,268,879.88 | 8 | 3,962,469.95 | 1,690,487.50 | 1,600,789.90 | 40 | 2,927,286.48 | 423,316.00 | 0.35 | 39,923,533,214,707.50 | 2.51 | 0.10 | ||

| Formal volunteering in population ratio (%) | 2.69 | 16.00 | 0.83 | 2.46 | 0.72 | 17.00 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 10 | 0.98 | 0.54 | 1.47 | 43.00 | 1.21 | 1.15 | 0.78 | 38.00 | 32.01 | 0.00 | ||

| Informal volunteering in population ratio (5) | 2.73 | 16.00 | 0.41 | 2.77 | 2.55 | 17.00 | 1.39 | 2.95 | 1.93 | 10 | 1.54 | 2.52 | 2.47 | 43.00 | 1.19 | 2.76 | 0.27 | 4.19 | 1.53 | 0.23 | ||

| Total volunteering in population ratio (%) | 5.42 | 16.00 | 0.94 | 5.59 | 3.19 | 17.00 | 1.40 | 3.41 | 2.71 | 10 | 2.13 | 3.34 | 3.91 | 43.00 | 1.86 | 3.99 | 0.64 | 59.70 | 14.03 | 0.00 | ||

Appendix C. The Ranking Anomaly

| UNV Volunteerism Country Ranking Based on Raw Numbers (1 = Highest Number) | UNV Volunteerism Country Ranking Based on Modified Real Numbers, Where Numbers Were Divided by Population before Ranking (1 = Highest Number) | UNV Formal Volunteerism Country Ranking Based on Raw Numbers (1 = Highest Number) | UNV Formal Volunteerism Country Ranking Based on Modified Real Numbers, Where Numbers Were Divided by Population before Ranking (1 = Highest Number) | |

| United States of America | 1 | 9 | 1 | 9 |

| China | 2 | 38 | 2 | 33 |

| India | 3 | 40 | 3 | 36 |

| Mexico | 4 | 13 | 9 | 28 |

| Germany | 5 | 16 | 4 | 15 |

| France | 6 | 11 | 7 | 14 |

| United Kingdom | 7 | 14 | 5 | 12 |

| Canada | 8 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

| Japan | 9 | 37 | 8 | 24 |

| Brazil | 10 | 24 | 11 | 21 |

| Turkey | 11 | 34 | 30 | 41 |

| Italy | 12 | 32 | 10 | 23 |

| Poland | 13 | 17 | 18 | 29 |

| Spain | 14 | 27 | 16 | 31 |

| Australia | 15 | 15 | 13 | 11 |

| Netherlands | 16 | 6 | 12 | 5 |

| Romania | 17 | 29 | 29 | 35 |

| Chile | 18 | 25 | 20 | 22 |

| Sweden | 19 | 4 | 14 | 3 |

| Austria | 20 | 5 | 17 | 7 |

| Greece | 21 | 19 | 19 | 13 |

| Czech Republic | 22 | 28 | 32 | 34 |

| Korea | 23 | 39 | 15 | 32 |

| Denmark | 24 | 7 | 24 | 10 |

| Switzerland | 25 | 23 | 26 | 18 |

| Norway | 26 | 8 | 21 | 6 |

| New Zealand | 27 | 2 | 22 | 4 |

| Hungary | 28 | 35 | 37 | 38 |

| Portugal | 29 | 36 | 25 | 20 |

| Bulgaria | 30 | 31 | 39 | 39 |

| Finland | 31 | 20 | 27 | 16 |

| Slovakia | 32 | 30 | 40 | 37 |

| Croatia | 33 | 21 | 31 | 26 |

| Ireland | 34 | 26 | 28 | 17 |

| Lithuania | 35 | 12 | 41 | 40 |

| Latvia | 36 | 18 | 35 | 25 |

| Slovenia | 37 | 33 | 36 | 30 |

| Estonia | 38 | 22 | 38 | 27 |

| Cyprus | 39 | 10 | 33 | 8 |

| Luxemburg | 40 | 3 | 34 | 1 |

| Belgium | 23 | 19 |

References

- UNV. Global Synthesis Report Plan of Action to Integrate Volunteering into the 2030 Agenda; UNV: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Haski-Leventhal, D. Altruism and Volunteerism: The perceptions of altruism in four disciplines and their impact on the study of volunteerism. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2009, 39, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.A. Markets, Games, and Strategic Behavior: An Introduction to Experimental Economics, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schermerhorn, J.R.; Davidson, P.; Woods, P.; Simon, A.; Poole, D.; McBarron, E. Management: Foundations and Applications, 2nd Asia Pacific ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Handy, F.; Cnaan, R.A.; Hustinx, L.; Kang, C.; Brudney, J.L.; Haski-Leventhal, D.; Holmes, K.; Meijs, L.C.P.M.; Pessi, A.B.; Ranade, B.; et al. A cross-cultural examination of student volunteering: Is it all about résumé building? Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2010, 39, 498–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; Hudson, S.; Hassay, D.N. The Marketing of Employee Volunteerism. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAF. Corporate Giving by the FTSE 100; Charities Aid Foundation: Kent, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. Altruism and economics. East. Econ. J. 1992, 18, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. Altruism and economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kolk, A. The social responsibility of international business: From ethics and the environment to CSR and sustainable development. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D.; Bargal, D. The volunteer stages and transitions model: Organizational socialization of volunteers. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 67–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, C.; Paine, A.E.; Howlett, S.; Zimmeck, M. Volunteering and Society in the 21st Century; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kende, A.; Lantos, N.A.; Belinszky, A.; Csaba, S.; Lukács, Z.A. The politicized motivations of volunteers in the refugee crisis: Intergroup helping as the means to achieve social change. J. Soc. Political Psychol. 2017, 5, 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, H.A.; Dann, S.L.; Dirkx, J.M. Motivations of adults for non-formal conservation education and volunteerism: Implications for programming. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2009, 8, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, W.; Riecken, G.; Yavas, U. Determinants of Volunteerism. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 1997, 4, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpék, É. Formal and informal volunteering in Hungary: Similarities and differences. Corvinus J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2012, 3, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, P. Doing Good By Doing Good: Why Creating Shared Value is the Key to Powering Business Growth and Innovation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Millora, C. Volunteering Practices in the Twenty-First Century; UNV: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cnaan, R.A.; Handy, F.; Wadsworth, M. Defining who is a volunteer: Conceptual and empirical considerations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 1996, 25, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D.; Roza, L.; Meijs, L.C.P.M. Congruence in corporate social responsibility: Connecting the identity and behavior of employers and employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D.; Meijs, L.C.P.M.; Hustinx, L. The third-party model: Enhancing volunteering through governments, corporations and educational institutes. J. Soc. Policy 2010, 39, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetitnev, A.; Kruglova, M.; Bobina, N. The economic dimension of volunteerism as a trend of university research. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 214, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, A.; Takács, I.; Takács-György, K. The examination of non-profit and public institutions from the CSR viewpoint. Zarządzanie Publiczne 2012, 2, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicher, R. Brainbay Centre—Responsibility from Two Sides. Scientific Papers of The Silesian University of Technology Organisation and Management Series. Available online: https://www.polsl.pl/Wydzialy/ROZ/ZN/Documents/Zeszyt%20137/Reicher.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Bowen, G.A.; Burke, D.D.; Little, B.L.; Jacques, P.H. A comparison of service-learning and employee volunteering programs. Acad. Educ. Leadersh. J. 2009, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chief Executives for Corporate Purpose. Giving in Numbers, 2019th ed.; CECP: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deresky, H.; Christopher, E. International Management: Managing Cultural Diversity; Pearson: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dalglish, C.; Miller, P. Leadership—Modernising our Perspective, 2nd ed.; TUP Textbook: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Halbusi, H.A.; Tehseen, S. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): A literature review. Malays. J. Bus. Econ. 2017, 4, 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Boštjančič, E.; Antolović, S.; Erčulj, V. Corporate Volunteering: Relationship to job resources and work engagement. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The CIVIC 50. Participant Briefing Packet; Institute, P.o.L., Ed.; The Points of Light Institute: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Haski-Leventhal, D.; Roza, L.; Brammer, S. Employee Engagement in Corporate Social Responsibility; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rodell, J.B.; Breitsohl, H.; Schröder, M.; Keating, D.J. Employee volunteering: A review and framework for future research. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, M.G.; Gibsron, C.C.; Kim, J. Developing Excellence in Workplace Volunteer Programs: Guidelines for Success; KPMG, Ed.; KPMG—The Points of Light Institute: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cycyota, C.S.; Ferrante, C.J.; Schroeder, J.M. Corporate social responsibility and employee volunteerism: What do the best companies do? Bus. Horizons 2016, 59, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N. Who’s tops in corporate reputation? Corp. Reput. Rev. 2000, 3, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Points of Light. The CIVIC 50: Strategic Stewards Tackle Societal Issues; Points of Light: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- True Impact. ROI Tracker. Available online: http://www.trueimpact.com/supplemental-csr-services/volunteerism (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Mirvis, P. Employee engagement and CSR: Transactional, relational, and developmental approaches. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2012, 54, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auginis, H.; Villamor, I.; Gabriel, K.P. Understanding employee responses to COVID-19: A behavioral corporate social responsibility perspective. Manag. Res. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vveinhardt, J.; Sroka, W. Workplace mobbing in polish and lithuanian organisations with regard to corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windsor, T.D.; Anstey, K.J.; Rodgers, B. Volunteering and psychological well-being among young-old adults: How much is too much? Gerontologist 2008, 48, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElhaney, K.A. strategic approach to corporate social responsibility. Lead. Lead. 2009, 2009, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuri, J.N.; Matten, D.; Moon, J. Employee Volunteering and social capital: Contributions to corporate social responsibility. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- True Impact. Mentors, Managers, and Painters: How employee Volunteerism Creates Value for Society and for Your Business. Available online: http://cdn2.hubspot.net/hub/35299/file-25189739-pdf/docs/2013_volunteerism_roi_tracker_findings.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Madison, T.F.; Ward, S.; Royalty, K. Corporate social responsibility, organizational commitment, and employer- sponsored volunteerism. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, A.; Hasan, M.M. Corporate social responsibility and cost stickiness. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 453–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, D.; Runte, M.; Basil, M.; Usher, J. Company support for employee volunteerism: Does size matter? J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Morris, T.; Young, B. The effect of corporate visibility on corporate social responsibility. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Patel, S.; Ramani, S. The role of mutual funds in corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.K. Recruitment strategies for encouraging participation in corporate volunteer programs. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 49, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, K.; Mallya, P.D. Managerial decision-making process in CSR: Employee volunteering. J. Strategy Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kolnhofer-Derecskei, A.; Reicher, R.; Szeghegyi, Á. The X and Y generations’ characteristics comparison. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2017, 14, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaVigna, S.; List, J.A.; Malmendier, U.; Rao, G. The importance of being marginal: Gender differences in generosity. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkhanda, E.; Saima, M.A.; Hina, S. Impact of motivation behind volunteerism on satisfaction with life among university students. Peshawar J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. (PJPBS) 2017, 3, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, W.W.; Samu, S. Volunteer service as symbolic consumption: Gender and occupational differences in volunteering. J. Mark. Manag. 2002, 18, 971–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson Dane, K. Benefits of participation in corporate volunteer programs: Employees’ perceptions. Pers. Rev. 2004, 33, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, S.M.; Gabel, J.T.A.; Williams, D.W. Connecting the two faces of CSR: Does employee volunteerism improve compliance? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, J.A.; Price, M.K. Charitable giving around the world: Thoughts on how to expand the pie. CESifo Econ. Stud. 2011, 58, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Points of Light. Seven Practices of Effective Employee Volunteer Programs; Institute, P.o.L.C., Ed.; The Points of Light Institute: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- CAF. Corporate Giving by the FTSE 100; Charities Aid Foundation: Kent, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, M.; Brown, W. Prosocial Behavior in the Time of Covid-19: The Effect of Private and Public Role Models; IZA Discussion Paper No. 13207; IZA: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EVS. European Values Study 2017: Integrated Dataset (EVS 2017); Archive, G.D., Ed.; EVS: Cologne, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerpfer, C.; Inglehart, R.; Moreno, A.; Welzel, C.; Kizilova, K.; Diez-Medrano, J.M.; Lagos, P.; Norris, E.B.P. World Values Survey: Round Seven—Country-Pooled Datafile, 7th ed.; Secretariat, J.S.I.W., Ed.; JD Systems Institute: Madrid, Spain; Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.C.; Haerpfer, A.; Moreno, C.; Welzel, K.; Kizilova, J.; Diez-Medrano, M.; Lagos, P.; Norris, E.B.P. World Values Survey: Round Six—Country-Pooled Datafile Version, 6th ed.; JD Systems Institute: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C.; Press, C.U. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Online, C. Available online: https://www.cafonline.org/ (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- MSCI. MSCI KLD 400 Social Index. Available online: https://www.msci.com/www/fact-sheet/msci-kld-400-social-index/05954138 (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Giese, G. Understanding MSCI ESG Indexes. Available online: https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/5b8d92f4-5427-5c8b-e57c-86b7b1466514 (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- MSCI. ESG Indexes. Available online: https://www.msci.com/esg-indexes (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Points of Light. The Civic 50. Available online: https://www.pointsoflight.org/the-civic-50/ (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Points of Light. The CIVIC 50 Participant Guide 2019; Points of Light: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chief Executives for Corporate Purpose. CECP Giving in Numbers. Available online: https://cecp.co/about/ (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Benjamin, E. A Look inside corporate employee volunteer programs. J. Volunt. Adm. 2001, 19, 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Geroy Gary, D.; Wright Philip, C.; Jacoby, L. Toward a conceptual framework of employee volunteerism: An aid for the human resource manager. Manag. Decis. 2000, 38, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, P.; Horowitz, P. The global employee volunteer: A corporate program for giving back. J. Bus. Strategy 2006, 27, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, T.R. Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Research Design, Measurement and Statistics; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- UNV. 2018 State of the World’s Volunteerism Report The Thread That Binds—Volunteerism and Community Resilience; UNV: Bonn, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, H.W.; Fancourt, D. Predictors of Engaging in Voluntary Work during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Analyses of Data from 31,890 Adults in the UK. SocArXiv, Ed.; Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/er8xd/ (accessed on 31 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Leigh, R. State of the World’s Volunteerism Report 2011. Universal Values for Global Well-Being; UNV United Nations Volunteers: Bonn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.S.; Sarkar, T.; Khan, S.H.; Mostofa Kamal, A.-H.; Hasan, S.M.M.; Kabir, A.; Yeasmin, D.; Islam, M.A.; Amin Chowdhury, K.I.; Anwar, K.S.; et al. COVID-19–related infodemic and its impact on public health: A global social media analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Youth and COVID-19 Impacts on Jobs, Education, Rights and Mental Well-being. In Survey Report 2020; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CAF. CAF Charity Coronavirus Briefing—3 Months into Lockdown, How are Charities in the UK Faring? Charities Aid Foundation: Kent, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CAF. The Voice of Charities Facing COVID-19 Worldwide I.; CAF America: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CAF. The Voice of Charities Facing COVID-19 Worldwide II.; CAF America: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work, 4th ed.; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work, 5th ed.; Updated Estimates and Analysis; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkney, S. What are People Thinking during Covid-19 in Terms of Giving? CAF Online: Kent, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Okun, M.A.; Schultz, A. Age and motives for volunteering: Testing hypotheses derived from socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol. Aging 2003, 18, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Jia, M. Integrating the bright and dark sides of corporate volunteering climate: Is corporate volunteering climate a burden or boost to employees? Br. J. Manag. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- True Impact. 3 Ways to Meet Nonprofit Needs During the COVID-19 Pandemic (Beyond Funding) + Survey Tool. Available online: http://www.trueimpact.com/social-impact-resources/3-ways-to-meet-nonprofit-needs-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-beyond-funding-survey-tool (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- ILO. Safe Return to Work: Ten Action Points—Practical Guidance; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, E.U. Giving the future a chance: Behavioral economic responses to the dual challenges of COVID-19 and the climate crisis. In The Behavioral Economics Guide 2020; Samson, A., Ed.; Behavioral Science Solutions Ltd.: London, UK, 2020; pp. 2–14. [Google Scholar]

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Employee level | |

| |

| Company-level | |

|

|

| Correlations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallup Ranking | Giving Helping Stranger | Giving Donating Money | Giving Volunteering Time | Philanthropic Rank | UNV Population Rank | UNV Formal Population | |||

| Spearman’s rho | Gallup Ranking | Correlation Coefficient | 1.000 | 0.694 ** | 0.807 ** | 0.980 ** | 0.617 ** | 0.348 * | 0.699 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 38 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 22 | 38 | 37 | ||

| Giving Helping Stranger | Correlation Coefficient | 0.694 ** | 1.000 | 0.809 ** | 0.686 ** | 0.515 * | 0.577 ** | 0.660 ** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 33 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 23 | 37 | 36 | ||

| Giving Donating Money | Correlation Coefficient | 0.807 ** | 0.809 ** | 1.000 | 0.824 ** | 0.617 ** | 0.585 ** | 0.732 ** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 33 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 23 | 37 | 36 | ||

| Giving Volunteering Time | Correlation Coefficient | 0.980 ** | 0.686 ** | 0.824 ** | 1.000 | 0.545 ** | 0.425 ** | 0.647 ** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 33 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 23 | 37 | 36 | ||

| Philanthropic Rank | Correlation Coefficient | 0.617 ** | 0.515 * | 0.617 ** | 0.545 ** | 1.000 | 0.702 ** | 0.717 ** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 22 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 26 | 26 | 25 | ||

| UNV Population Rank | Correlation Coefficient | 0.348 * | 0.577 ** | 0.585 ** | 0.425 ** | 0.702 ** | 1.000 | 0.753 ** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.032 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 38 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 26 | 43 | 41 | ||

| UNV Formal Population | Correlation Coefficient | 0.699 ** | 0.660 ** | 0.732 ** | 0.647 ** | 0.717 ** | 0.753 ** | 1.000 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 37 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 25 | 41 | 41 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kolnhofer Derecskei, A.; Nagy, V. Employee Volunteerism—Conceptual Study and the Current Situation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208378

Kolnhofer Derecskei A, Nagy V. Employee Volunteerism—Conceptual Study and the Current Situation. Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208378

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolnhofer Derecskei, Anita, and Viktor Nagy. 2020. "Employee Volunteerism—Conceptual Study and the Current Situation" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208378

APA StyleKolnhofer Derecskei, A., & Nagy, V. (2020). Employee Volunteerism—Conceptual Study and the Current Situation. Sustainability, 12(20), 8378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208378