Abstract

The previous research on the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and business performance produced mixed findings. Scholars exerted the mixed findings are largely influenced by several factors and contexts where different markets, type of companies, industries, and countries would show different results. On that basis, this study examines how the dimensions of objective environment influence the relationship between CSR dimensions and the business performance of Takaful agencies in Malaysia. Malaysia was chosen as the country because it is among the largest Takaful contributors in the world. Stakeholder and contingency theory are used to analyze the hypothetical relationship between the variables. Questionnaires were distributed to Takaful agency managers who operate their businesses in Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya, and Selangor state. About 211 of them participated in this study. The empirical findings suggest that economic and ethical activities have a direct influence on Takaful agencies’ business performance. Further results imply that while environmental dynamism influences business performance directly, environmental complexity significantly moderates the relationship between legal, philanthropy, and business performance. This research considered only the direct effect of CSR activities and the moderating effect of environmental dimensions on business performance with only the agency managers’ perspective studied. It adds new insights to the CSR and Takaful literature by revealing the relationship between the dimensions of CSR and business performance in the Takaful context, and sheds light on how governing authorities and Takaful operators should implement the CSR strategy and activities to make the industry successful in Malaysia and around the world, as Takaful businesses are heading towards becoming a global industry.

1. Introduction

Takaful or Islamic insurance is becoming popular in the Muslim world. It is an alternative to conventional insurance [1], which plays a significant role in the world economy [2]. The insurance system helps people to switch or safeguard the risk of uncertainty of the modern world [1]. The formal Takaful operation system relies heavily on Shariah principles such as mutual responsibility, cooperation, and mutual protection [3].

Takaful institutions began in Sudan in 1979 followed by other countries around the world. Malaysia and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries are considered as the leading key players in the global Takaful market [4]. Moreover, countries in Europe such as United Kingdom, Germany, and France have also started introducing and expanding Takaful businesses where they are perceived as among the largest market for Takaful in the world [5]. The development of the Takaful industry in Malaysia started in the 1980s where Syarikat Takaful Malaysia became the first Takaful operator, established in 1985. Generally, global gross Takaful contribution has seen double-digit growth since 2010. At present, the Takaful market in Malaysia is showing steady growth in spite of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has hit hard many industries including global financial and insurance sectors [6]. From the Islamic point of view, there is a similarity between the Takaful concept and social responsibility [7].

Previous researchers argued that Takaful operators should embrace technology in all operational, sales, and marketing strategies [8]. They need to adopt more effective strategies and communication tools as well as more innovative approaches in acquiring and retaining customers [5]. The application of societal and marketing concepts can make the industry more competitive [5,9]. Ho et al. (2018) [10] stated that practicing social responsibility activities is important for the long-term success of insurance companies. According to Carroll (1991) [11], it is a legal right and core responsibility of business to maximize profit, yet this does not give firms the right to exploit the scarce natural resources, harm the natural and ecological environment, abuse customer and labor rights to maximize the profit. Economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropy are four important dimensions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) [12,13], where firms must go beyond the legal and economic responsibilities in order to serve the larger stakeholders, including owners, employees, customers, suppliers, environment, and the society at large.

Based on the stakeholder theory, a firm’s fiduciary responsibility is to safeguard the legitimate interest of not only shareholders but other stakeholders, especially society and the natural environment that ultimately leads the firm to total corporate social responsibility, optimal performance, and sustainability in the long run. This is consistent with the views concerning the responsibilities of a firm that have changed where they cover not only its owners and shareholders but other stakeholders too [14]. Although the development of stakeholder theory is minimal, it is still regarded as the most relevant and important theory for corporate social performance assessment and for understanding the structures and dimensions of business and society relationships [15]. In other words, corporate social performance will be understood within stakeholder theory framework where, ultimately, firms can engage more fully in their societal relationships and duties [15]. Correspondingly, the stakeholders are demanding not only ethical corporate conduct but also information about corporate ethical conduct [16]. Although financial performance is still the main goal of a business, it would be appropriate for a firm’s activities to be aimed at corporate sustainability, and for government regulations to act as an important stimulant for firms to implement sustainability plan of action. In addition, the market can also generate demand for sustainable business through stakeholder pressure [17].

The concept of Takaful is similar to the concept of social responsibility [7] where the CSR concept inherits the notion of sustainability because socially responsible firms utilize resources efficiently and effectively to achieve sustainable development [18]. Several researchers [19,20] suggested that insurance firms play an important role to eradicate poverty and inequality among societies with their products. Similarly, Takaful, which is governed under the Shariah principles and mutual protection, allows the policyholders to share the risk collectively and agree to protect each other from damage or loss voluntarily through cooperation and donation [21]. Several researchers have shown a positive relationship between CSR practices and good brand image [22], customer intention to purchase [23,24], and employee’s commitment [25].

As a result, some scholars emphasized examination of the role of CSR on brand image and corporate reputation in Malaysian Takaful context [26], to determine the influence of companies’ CSR disclosure behavior on firms’ financial performance in insurance companies (both conventional and Takaful) [27]. Although these studies provide valuable insight regarding the influence of CSR in organizations, how the several dimensions of CSR activities influence the business performances of Islamic insurance companies has not been scrutinized properly in early research.

Furthermore, previous studies found a mixed result regarding the influence of CSR on firm performance [28,29,30]. While a positive relationship between CSR activities and firm performance was documented in the Western developed economy, a mixed result was found regarding the relationship between CSR activities and firm performance in an emerging economy like China [31]. Manokaran et al. (2018) [27] also found mixed results regarding the influence of CSR action to organizational financial performance in the context of Malaysian insurance companies (both the conventional insurance and Takaful systems). Previous researchers argued that environmental factors might moderate the relationship between organizational strategy and firm performance [32]. To clarify the reason behind the paradoxical relationship between CSR activities and firm performance, Bai and Chang (2015) [31] examined market turbulence as a mediator between CSR activities and firm performance; and documented environmental factors (competitive intensity and market turbulence) as a moderator between market turbulence and the firm performance. A recent study also proposed that environmental factors might moderate the relationship between CSR and firm performance in the Takaful context [33]. However, the moderating effect of environmental factors between CSR activities and firm performance in the Takaful context is comparatively less explored.

Therefore, this study argues that an empirical study regarding the relationship between the dimensions of CSR activities (economic, ethical, legal, and philanthropy) and firm performance, as well as the moderating effect of the objective environmental factors (complexity, dynamism, and munificence) is crucial in a Takaful context. This is because the revealed relationship would be able to provide a deeper understanding regarding the relationship between CSR and firm performance, as well as how unique environmental factors (complexity, dynamism, and munificence) influence this relationship in a potential sector of Takaful industry in Malaysia. The current study posits that the findings would be able to shed light on the reason behind the paradoxical findings between the relationship of CSR activities and firm performance, as well as pointing out ways in which Takaful operators and agencies in Malaysia could improve their performance based on the concept of CSR activities; consequently improving the growth of the Takaful industry in years to come. This paper begins with brief introduction of Takaful industry, i.e., concept, history, and its industry development, followed by discussion on corporate social responsibility, i.e., its dimensions and relationship with firm performance. The next section discusses CSR and firm performance in the literature as well environment as a moderating construct followed by hypotheses development. The third section explains the methodology, i.e., sampling design, procedures, and measurement instrument. The fourth section is about data analysis and results. The fifth section describes the theoretical implication and managerial contribution of the study. Finally, limitations and future research suggestions are exhaustively discussed.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Firm Performance

CSR has been an important and interesting subject of research in businesses for decades [30]. It refers to the obligation of the businessmen to pursue policies, decisions, and lines of action which are desirable in society [34]. It has also been defined as the company’s status and activities with respect to perceived societal or, at least stakeholder, obligations [35]. CSR is an extra-role behavior that not only emphasizes the economic benefit, but also includes activities that are beneficial for the society [36]. The classical view of the concept postulated that CSR entails activities meant to generate and increase profit only [37]; while the instrumental theory asserts that organizations should support social activities to gain a good image and competitive advantage [38]. Indeed, a corporation should fulfill the expectations of society and different stakeholders [26] to survive in business [39,40].

Several scholars found that CSR activities have a significant effect on business performance [41,42]. Business performance covers the external performance of an organization based on economic valuation as well as internal performance outcomes that are associated with operational efficiency and effectiveness [43]. It includes the performance of finance, business, and organizational effectiveness [44,45], which further satisfy the organization’s survival needs and stakeholders’ needs [46].

Economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropy are four important dimensions of CSR [12,13,47]. The triple bottom line approach of CSR that incorporates social, environmental, and economic dimensions in the CSR model has become the basis for the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) for sustainability reporting [48]. The economic responsibility of an organization embraces activities such as operation efficiency activities, creating jobs and fair pay for employees and providing a return of investment (ROI) to shareholders [49], as well as other economic activities to its stakeholders [11]. The legal dimension entails organizational responsibility to adhere to rules and regulations [12]. Ethical responsibility embraces activities that are not necessarily legalized [49] but based on religion and commitment towards humane principles and human rights [50]. Finally, philanthropy responsibility encompasses activities that promote human welfare [11]. Although the concept of CSR is widely discussed from a different theoretical point of view, the stakeholder concept is still central to CSR practice [51].

The CSR initiative can be tangible or intangible and may provide monetarily to psychological benefits [52]. The CSR practices of an organization can motivate consumers to purchase a product from their brand [53]. It helps to achieve a good and favorable position in an extremely competitive market [27]. The dimensions of CSR (economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic) positively influence an organization’s brand image and corporate reputation [26]. Lee at al. (2012) [54] revealed that the economic and philanthropic dimensions of CSR have a positive influence on organizational trust, and ethics has a positive effect on relationship outcome. Furthermore, a recent study on insurance companies, including Takaful, found that CSR can influence organizations’ return on assets (ROA) positively, and earnings per share (EPS) negatively, while it does not have any significant relationship with return on equity (ROE) [27]. Bai and Chang (2015) [31] showed that CSR activities through marketing competence can influence firm performance. Therefore, this study argues that since CSR has either a direct or indirect effect on firm performance, thus the dimensions of CSR practices of Takaful companies might influence firm performance. Thus, based on the above analysis the following four hypotheses have been developed.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Economic CSR has a significant positive influence on the business performance of Takaful agencies.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Ethical CSR has a significant positive influence on the business performance of Takaful agencies.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Legal CSR has a significant positive influence on the business performance of Takaful agencies.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Philanthropic CSR has a significant positive influence on the business performance of Takaful agencies.

2.2. Environment as Moderator

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has received increasing attention from both academics and practitioners for the past few years [55]. CSR is important for a firm to manage societal uncertainties with present dynamic, global, and technological social contexts [56]. CSR is portrayed as an organization’s obligation for the environment and stakeholders in a manner that goes beyond financial aspects of a firm [57]. The role of CSR in influencing organizations’ performance has been frequently discussed in the literature. Many scholars in studies of CSR have been trying to investigate whether CSR and firm performance are positively or negatively related [55]. It is believed that understanding the relationship between CSR and economic performance is crucial even if a firm undertakes CSR for strategic objectives or noble reasons [58].

Freeman (1994) [59] exerted that social performance is needed to attain business legitimacy and anticipated the correlation between social responsibility and financial performance. It is further suggested that, in the long run, it will be a positive relationship between social responsibility and financial performance [59]. Many studies were conducted to examine the relationship between environmental practices (part of CSR) and firm performance in terms of environmental strategies, eco-design, innovation, and corporate social responsibility [60]. Roman et al. (1999) [61] exerted most past studies showed a positive relationship between corporate social practices and financial performance. This argument is consistent with the view of other scholars who described mixed evidence in the relationship, but most studies were found to show positive relationship [62]. While some studies found CSR as an increaser of business performance [26,41,42], other scholars documented negative [63] or no relationship [54] between the CSR practices of an organization and its performance. Even though scholars found mixed results of correlation between social responsibility and financial performance, society still desires a firm to implement good social responsibility and environmental management practices [64].

Researchers argued that a lack of focus on the market segment or industry effect might be a reason behind the paradoxical relationship between CSR and firm performance [65]. Generally, an organization may be affected by various environmental factors [66] such as environmental volatility and complexity [67], and an organization might face trouble if it attempts to ignore environmental factors [66]. Generally, objective environment has become a commonly researched dimension [49]. Moreover, several researchers exerted that it is the objective environmental factor that can affect performance [50]. The objective environment can be categorized into task and general [68]. Social, political, economic, demographic, and technological trends are within the domain of general environment. Whereas task environment conveys how an organization interconnects with customers, competitors, suppliers, and other stakeholders [69]. The task environment condition consists of three dimensions; complexity, dynamism, and munificence [70].

Environmental complexity refers to the heterogeneity of the market [70]. Heterogeneity indicates distinct market segments in which the company operates [71,72]. Companies which operate in heterogeneous markets usually face greater complexity than those companies in homogenous markets [73]. Dynamism relates to the rate of unpredictable change in a firm’s environment [74], more specifically, the uncertainty that may minimize managers’ ability to anticipate the future and its impact on an organization [75]. Munificence refers to the extent of the competition that can exist based on the insufficiency and abundance of critical resources [71] that influence the growth of firms within the boundary of the environment in providing sufficient resources for firms [76]. A slow growth market might be extremely munificent if it contains few competitors [71].

Previous researchers argued that environmental dynamism and munificence might moderate the relationship between variables [77]. Nazri and Omar (2016) [33] also proposed an objective environment (dynamism, munificence, and complexity) as a moderator between CSR and Takaful agency performance in Malaysia. While Bai and Chang (2015) [31] found market environment (competitive intensity and market turbulence) to be a moderator between the relationship of CSR practices and marketing competency; the role of the dimensions of objective environment between CSR and firm performance is yet to be understood. Therefore, this study argues that since firm performance largely relies on the external environment and internal competencies of an organization [60], and there is empirical evidence regarding the moderating effect of market environment between CSR and firm performance [33], objective environment might moderate the relationship between the variables of CSR activities and business performance. Thus, based on the above research findings, the following hypotheses are developed:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The environmental complexity can moderate the relationship between CSR activities and the business performance of Takaful agencies.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

The environmental dynamism can moderate the relationship between CSR activities and the business performance of Takaful agencies.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

The environmental munificence can moderate the relationship between CSR activities and the business performance of Takaful agencies.

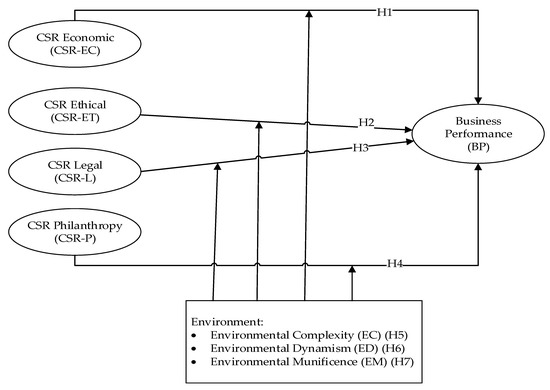

Figure 1 shows the proposed relationship among the variables of corporate social responsibility, objective environment, and business performance.

Figure 1.

The model showing the proposed relationship between the variables.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling Design and Procedures

This study involves data collection from Takaful agencies in three states (Kuala Lumpur, Wilayah Persekutuan Putrajaya, and Selangor) of Malaysia. Malaysia is one of the top players of Takaful markets in the regional markets, which are largely supported by government and socio-economic demographics [1]. Besides, the country is becoming a global Takaful leader where it has a relatively high ratio of average gross written contributions per Takaful operator, which is approximately 27% of the global market [78]. The CSR practices of the insurance companies in Malaysia are also quite satisfactory [79]. The Malaysian Government takes different initiatives to promote the CSR activities of the organizations [80]. Therefore, this study chooses the Malaysian Takaful industry for further research. Kuala Lumpur, Wilayah Persekutuan Putrajaya, and Selangor state were selected for this research because most Takaful agencies are likely to operate their businesses in these states because of a high density of customers and the Takaful operators’ head offices and agencies within these areas.

To ensure the questionnaire’s face and content validity, a pre-test was conducted. The draft of the questionnaire was emailed to four experts in this area for comments and feedback. After three weeks the feedback was sent from the experts and the final draft of the questionnaire was prepared after doing the necessary corrections. A drop-off and pick-up approach was employed to collect the data.

A total of 800 questionnaires were distributed to Takaful agency managers who are also owners of the agency (one agency is managed/owned by one manager) by following a judgmental sampling method. Out of 800 questionnaires distributed, only 227 questionnaires were received, representing a response rate of 28.38% in this study. However, Churchill (1995) [81] argued that response rates ranging from 12–20% are considered acceptable for cross-sectional study. This study included confidential information such as Takaful agencies’ monthly contribution collection in the questionnaire; this might be a reason behind the low response rate [82,83].

To avoid the common method bias, several procedural remedies were employed by following the recommendations of early scholars [84]. For example, measurement items from different sources were employed, the anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents and organizations were ensured, the measurement items were refined after preliminary study, and respondents were informed that there is no right or wrong answer provided in the questionnaire. Most of Takaful agencies are categorized as small and medium enterprise (SMEs). Thus, the possibility of common method variance is reduced as SMEs managers in Takaful agencies are more likely to carry multiple roles and responsibilities, work with fewer organizational levels or people, and have a broader job scope [85]. In addition, this study also employed Harman’s single-factor test as a statistical remedy recommended by [84,86].

3.2. Measurement Instrument

The key constructs of the current study were operationalized by using a reflective measure. All the items were adapted from existing literature, where necessary changes were made to suit the local context and purpose of study [87]. A five-point Likert scale was adopted to examine how strongly subjects agree or disagree with the statement. The measurement items of CSR scales were adapted from early studies [47,88]. A total of 14 items were used to measure the dimensions of economic (3), ethic (4), legal (4), and philanthropic (3) of CSR activities. The CSR dimensions were measured by using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. A total of seven items were adapted from [89] to measure business performance. Respondents were asked to indicate their agencies’ business performance for the past three years by using a scale where 1 = greatly decreased, 3 = same as before, and 5 = greatly increased. For the moderators, a total of 14 items were adapted from [70,71] to measure the dimensions (dynamism, munificence, and complexity) of the variable environment. The respondents were asked to indicate the degree of changes where 1 = never changes; 5 = changes very often. The research model of this study was analyzed by using partial least squares-structural equation model (PLS-SEM).

Generally, there are two well defined SEM techniques, namely covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) and partial least squares-SEM (PLS-SEM) which focuses on the variance analysis [90]. PLS is a soft modeling SEM technique with no assumptions about data distribution [91]. SEM can be adopted to analyze the definition of latent constructs within the context of a group of causal effects [92]. In addition, SEM simultaneously estimates within a single, inclusive, and systematic procedure, both the measurement and structural model [92]. Specifically, PLS-SEM is useful in applied research especially when the participants are limited and the data distribution is skewed [90]. Thus, PLS was adopted in the study since the participants were only Takaful agency managers (one agency has one Takaful manager) and the number of respondents was only 211. Moreover, PLS can successfully explain complex models or relationships [93] which is appropriate for this research.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Data Analysis

Out of 800 questionnaires distributed to Takaful agencies managers, 227 questionnaires were returned showing a response rate of 28.38%. Among them, 16 responses were excluded due to incomplete answers, thus the ultimate valid responses were 211. This study analyzed the skewness and kurtosis suggested by [94] to check the normality. The result reveals that the skewness and kurtosis value of the data are less than 3 and 10, respectively, which ensures the normality of the data [95].

The descriptive analysis shows that 70.6% of the respondents are males, whereas the female respondent are only 29.4%. The major age group of the respondents (39.3%) is between 36 to 45 years old. The educational background of the respondents shows that 37.9% hold a certificate or diploma, 31.3% hold a degree and the remaining 17.1% hold a postgraduate degree. However, the majority of Takaful agencies have more than 10 agents which accounted for 64.9%, 24.2% have six–10 agents, and only 10.9% have less than five agents.

4.2. Assessment of Common Method Bias

The measurement of the construct in this study relies on the judgment by Takaful agency managers. Thus, there is a potential for single-respondent bias or common method bias as it implemented the cross-sectional data collection method from a single respondent by using a similar questionnaire [96]. As a statistical remedy, it employed Harman’s single-factor test [86]. The basic assumption of Harman’s single-factor test is that a factor analysis of all data that result in a single factor indicates a common method variance. The result shows that a single factor does not explain a majority of the variance as it only explains 36.01% of the variance. Therefore, it is suggested that the common method bias is not an issue for this study.

4.3. Measurement Model Evaluation

SEM analysis involves two steps where the first step is the latent variables validation followed by the second step to validate the hypotheses [97]. This study assessed the factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) for all the constructs to determine the validity and reliability of the latent variables. The results in Table 1 found that the item loadings of the variables are ranging from 0.541 (EM5) to 0.914 (CSR-EC2) except for one item of the variable ‘Business performance’ (BP1 0.269). Hair et al. (2016) [94] stated that an indicator with a value of less than 0.40 must be removed. The authors further argued that if the value of an indicator is more than 0.40 but less than 0.70, it should be remained due to content validity unless removing it significantly changes the composite reliability or value of AVE [94]. Therefore, this research removed the item BP1 (0.269) from the measurement model due to the lower factor loadings.

Table 1.

Result of measurement model.

It further checked the composite reliability values of all the constructs to determine the internal consistency reliability as recommended by [94]. The result reveals that the composite reliability values of all the constructs are ranging from 0.795 (CSR Philanthropic) to 0.919 (BP and CSR Economic), which are above the threshold value of 0.7 [94]. Thus, the findings indicate the internal consistency reliability of the constructs. The AVE values of all the constructs are also ranging from 0.527 to 0.803 which exceeds the cut-off level of 0.5. Thus, it ensures the convergent validity of the study constructs.

Finally, this study examined the discriminant validity of the scale by using the Fornell–Larcker criterion [98] approach. For this, the square root of the AVE values of a latent variable was compared with its correlations with the other latent variables. The result (Table 2) shows that the square root of AVE for each construct was greater than its correlation with any other constructs, thus indicating satisfactory discriminant validity of the model.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity assessment (Fornell–Larcker Approach).

4.4. Structural Model Evaluation

This study hypothesized four direct relationships between CSR and firm performance. The Hypotheses H1 to H4 proposed that the dimensions of CSR such as economic, ethical, legal, and philanthropy have a positive relationship with business performance (BP). Furthermore, another three hypotheses (H5, H6, and H7) were proposed to determine the moderating effect of the environmental variables (dynamism, munificence, and complexity) on the relationship between the four CSR dimensions and BP. The multi-collinearity issues of the model were examined by using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The results reveal that the largest VIF value of all variables was 4.417 (BP 3), which is less than the suggested threshold value of 5 [99]. Thus, it ensures that multi-collinearity is not an issue for the current study. This study found that the R2 value for the BP is 0.456 which is satisfactory [94].

Table 3 presents the direct relationship between the variables. The results also reveal that the dimensions CSR economic (β = 0.251, t = 2.502) and CSR ethics (β = 0.186, t = 2.610) have a positive relationship with BP, thus supporting hypotheses H1 and H2. However, this study did not find any significant relationship between CSR legal (β = −0.107, t = 1.1405), and CSR philanthropic (β = 0.057, t = 0.803) with BP. The results reject the hypotheses H4 and H5 and propose that there is a positive influence of CSR legal and CSR philanthropic on the business performance of Takaful agencies. Bai and Chang (2015) [31] found that marketing competence fully mediates the relationship between CSR and firm performance. This might be the reason why this study found an insignificant relationship between CSR legal, CSR philanthropic and business performance.

Table 3.

Results of the structural model analysis.

Table 4 presents the moderating effect of the environmental dimensions between CSR activities and firm performance. The hypotheses H5, H6, and H7 proposed the moderating effects of environmental complexity, environmental dynamism, and environmental munificence, between the relationship of four CSR dimensions (economic, ethic, legal, and philanthropy) and BP. One of the objectives of this study was to ensure if there is any moderating effect of the environmental dimensions between the four CSR dimensions and BP, thus this study applied the two-stage approach of PLS-SEM for determining the moderating effect following the recommendation of Hair et al. (2016) [93]. Table 4 shows the simple effect of the four dimensions of CSR and moderating variables on business performance. In Table 4, Model 1 adds the interaction terms between the four dimensions of CSR and environmental dynamism. Model 2 adds the interaction terms between the four dimensions of CSR and environmental complexity. Finally, Model 3 adds the interaction terms between the four dimensions of CSR and environmental munificence.

Table 4.

Regression analyses for moderating effects.

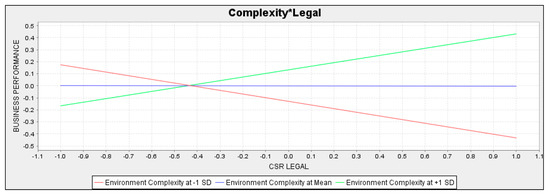

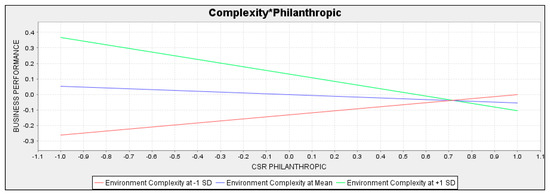

Model 1 shows that although the simple effect of the four CSR dimensions on business performance is significant, the moderating effect of the environment dynamism between CSR economic (β = 0.135, t = 0.833), CSR ethics (β = −0.136, t = 1.610), CSR legal (β = −0.139, t = 1.084), and CSR philanthropic (β = 0.125, t = 1.135) are not statistically significant, thus it rejects the hypothesis H6. Model 2 shows that environmental complexity moderates the relationship between CSR legal (β = 0.301, t = 1.821), CSR philanthropic (β = −0.182, t = 1.803), and business performance. However, this study did not find any moderating effect of environmental complexity between the relationship of CSR economic (β = −0.019, t = 0.132), CSR ethics (β = −0.029, t = 0.290), and business performance. Thus, the findings support the hypothesis H5 partially.

The findings suggest that the relationship between CSR legal (−0.002), CSR philanthropic (−0.053), and business performance is insignificant for an average level of environmental complexity. Nevertheless, if the environmental complexity increased by one standard deviation unit, the relationship between CSR legal and business performance will increase (Figure 2) by 0.299 (size of the interaction term) and the relationship between CSR philanthropic and business performance will decrease (Figure 3) by −0.235. The negative relationship between CSR philanthropic and business performance supports early studies [100] which also found a negative relationship between environmental expenditure (philanthropic) and firm performance. Furthermore, model 3 in Table 4 reveals that the environment munificence cannot significantly moderate the relationship between the four dimensions of CSR and business performance, thus rejects the hypothesis H7 that the munificence can moderate the relationship between the CSR dimensions and business performance. The insignificant moderating effect of environmental dynamism and environmental munificence between the CSR activities and business performance oppose the early argument that dynamism and munificence might moderate the relationship between the variables [77].

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of environmental complexity between the corporate social responsibility (CSR) legal and business performance.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of environmental complexity between the CSR philanthropic and business performance.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implication

This study examined the direct relationship between the four dimensions of CSR and firm performance in the Takaful context in Malaysia and also examined the moderating effect of the three dimensions of the objective environment (complexity, dynamism, and munificence) between the CSR activities and firm performance. Overall, the results reveal that the CSR economic and CSR ethics dimensions have a significant influence on business performance, and there is a moderating effect of environmental complexity between the relationship of CSR legal, CSR philanthropic, and business performance. This study also found that environmental dynamism directly influences business performance while there is no direct or moderating effect of environmental munificence between CSR activities and firm performance.

One of the contributions of this study is it sheds light on the role of unique dimensions of CSR activities in influencing business performance in the Takaful context in Malaysia. Previous studies argued that the role of CSR on influencing corporate financial performance is yet to be fully understood [27]. Besides, the role of CSR activities might vary according to different organizational and cultural contexts [27] and, as a result, there is a need for such research in the Takaful context [33]. Therefore, by examining the relationship between CSR activities and business performance in Takaful context, this study addresses the lack of research in this area and extends the existing literature of CSR in a developing country context, namely Malaysia.

Secondly, this study considered firm performance from a broader perspective rather than more narrow economic criteria to depict the overall picture. Researchers argued that CSR activities not only provide monetary benefits but also render intangible or psychological benefits [47,52]. Therefore, business performance should be considered from both economic and psychological performance while conducting CSR research. Although, some early studies emphasized the relationship between CSR activities and brand image [26] in Takaful context, as well as how CSR activities influence insurance companies’ (including Takaful) financial performance [27], this study considered business performance from a broader perspective such as financial performance, operational performance, and satisfaction (employee, agent, and customer) and examined the influence of unique CSR dimensions on business performance. Therefore, this study added value in the existing literature by considering the business performance from an economic valuation as well as internal business performance.

Thirdly, by emphasizing stakeholder theory and contingency theory this study examined the Takaful managers’ perceptions regarding the influence of CSR activities on business performance. As stated by [26] that all four dimensions of CSR activities have indirect effects on firm performance, this study confirms that the dimensions of economic and ethics of CSR activities can directly influence the firm performance and there is no direct relationship between CSR legal, CSR philanthropy, and business performance. Furthermore, the current study examined the moderating effect of environmental dimensions (dynamism, munificence, complexity) between CSR activities and business performance. The findings reveal that environmental complexity moderates the relationship between CSR legal, CSR philanthropic, and business performance. Therefore, this study contributes to the existing literature by shedding light on the important role of economic CSR, ethical CSR, and the moderating role of environmental complexity in the Takaful context which has been emphasized less by early researchers compared to other areas.

Fourthly, early studies [31] examined the moderating effect of market environment (competitive intensity, and marketing turbulence) between the stakeholders’ CSR activities and firm performance, while the concept of objective environment developed by [70] are called as an effective means to measure environment [71]. Therefore, this study examined the moderating effect of environmental complexity, dynamism, and munificence between CSR dimensions and firm performance. The findings reveal that, in a highly complex environment, the Takaful agencies’ emphasis on the organizational compliance behavior such as obeying law and regulations, ensuring fair operations, may influence the business performance positively. However, it also found that in a complex environment organizations’ philanthropy behavior influences the business performance negatively. Bai and Chang (2015) [31] also found that competitive intensity reduces the positive effect of CSR toward employees. Besides, it is assumed that philanthropic CSR might influence an organization’s performance when it suffers from a negative reputation [26]. Thus, by providing empirical evidence regarding the moderating role of unique environmental dimensions in the CSR research context, this study undoubtedly contributes to the existing body of knowledge and explains the complex relationship between the studied variables.

Finally, the model of this study could be used as a theoretical basis for further research in this area. Future research can examine the relationships between the mentioned variables for different stakeholders by using this model. Therefore, by opening the scope of further research, the model of this study contributes to CSR research, especially in the Takaful context.

5.2. Managerial Contribution

By considering CSR activities as a multidimensional construct and revealing the Takaful agency managers’ perceptions regarding the role of CSR dimensions in influencing firm perception, this study pointed out the role of CSR practices in Takaful context and how they can be used to increase the performance of Takaful agencies. It revealed that CSR economic activities (such as customer satisfaction, maintaining service quality, professional standards) and CSR ethical practices (such as fairness, trustworthiness, following Islamic law properly) can increase the business performance. Thus, by revealing the role of CSR economics and CSR ethics in the Malaysian Takaful context this study sheds light on how the Takaful managers, by emphasizing the CSR economic and CSR ethics dimensions, can influence the business performance positively and increase the market share in any environment. However, the revealed insignificant relationship between CSR legal, CSR philanthropic, and business performance indicates that the Takaful agency managers are still in doubt regarding the positive effect of CSR practices on society. Previous studies showed how CSR legal and CSR philanthropic indirectly increase firms’ competitive advantages [26]. Scholars also stated that “the benefits are not always quantifiable” [27]. Thus, the owners and managers of Takaful agencies should understand the intangible role of CSR legal and CSR philanthropic dimensions in an organization to ensure a long-term business success. Therefore, by critically examining the existing literature, this study shows the way organizations can develop an optimal CSR strategy. Furthermore, the current study found that while in a dynamic environment (where the technology, taste of customers rapidly changing) all four CSR dimensions can influence the business performance positively; in a highly complex or competitive environment, CSR legal activities have a positive effect on business performance, and the CSR philanthropic activities influence the business performance negatively. This finding indicates that practitioners and legislators should critically examine the environment while designing and implementing CSR strategies. Therefore, this study will help the Takaful authorities to come up with new ideas and policies; consequently, helping the Takaful industry to increase its market share compared to the general insurance system.

6. Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

The current study is subject to some limitations. Firstly, this study considered only the direct effect of CSR activities and the moderating effect of environmental dimensions on business performance. However, the previous study found brand image [26] and marketing competence [31] as mediators between CSR activities and firm performance. Therefore, future studies should consider the mediating effect to increase our understanding regarding the role of CSR practices in the Takaful context. Secondly, while this study used a survey method to collect the data, a face-to-face interview along with the survey method could provide more insight regarding the relationship between CSR practices and business performance as well as the current scenario of the CSR practices of the Takaful industry in Malaysia. Therefore, future studies should consider the mixed method approach to provide a deeper understanding of the relationship between the variables. Thirdly, this study considered only the employee or agency managers’ perspectives to examine the relationship between CSR and firm performance. However, customers are another most important group of stakeholders who can contribute to the firm’s performance significantly [101]. Therefore, future studies should consider the other group of stakeholders while examining the influence of CSR in the Takaful context. Finally, the replication of this study both in developed and developing country context is required to generalize the findings of the current study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and designed the study, M.A.N. and N.A.O.; data collection, N.A.R., N.A.O., A.A., and M.A.N.; software, N.A.O.; A.H.A.; A.A.; formal analysis, M.A.N. and N.A.O.; investigation, M.A.N.; resources, N.A.O., N.A.R.; data curation, N.A.O., M.A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.N., N.A.O.; writing—review and editing, M.A.N., N.A.O., A.A., A.H.A.; project administration, N.A.O., M.A.N.; funding acquisition, N.A.O. and M.A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FRGS/1/2018/SS03/UKM/02/8 (Fundamental Research Grant Scheme) and USIM/YTI/FEM/052002/41618.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers of this journal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al Mahi, A.S.M.M.; Sim, C.S.; Hassan, A.F. Religiosity and Demand for Takaful (Islamic Insurance): A Preliminary Investigation. Int. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. Res. 2017, 15, 485–499. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatty, A. The Growing Importance of Takaful Insurance. In Proceedings of the Asia Regional Seminar, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 23–24 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haron, S.; Azmi, N.W. Islamic Finance Banking System; McGraw-Hill: The Synergy, Singapore, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Hussin, M.F.; Muhamad, N.H.N.; Hussin, M.Y.M. Takaful (Islamic Insurance) Industry in Malaysia and the Arab Gulf States: Challenges and Future Direction. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, N. The Takaful & re-Takaful Industry: An Overview. Available online: https://www.islamicfinancenews.com/supplements/the-takaful-and-re-takaful-industry (accessed on 30 May 2012).

- The Star. 2020. Available online: https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2020/05/05/takaful-market-grows-despite-covid-19-malaysia-praised (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Yaacob, Y.; Azmi, I.A.G. Entrepreneur’s social responsibilities from Islamic perspective: A Study of Muslim Entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tahir, H. The Way Forward for Takaful Spotlight on Growth, Investment and Regulation in Key Markets; Deloitte & Touche (ME): Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, K. Development, Growth and Challenges of Takaful in Malaysia. Available online: https://www.islamicfinancenews.com/development-growth-and-challenges-of-takaful-in-malaysia.html (accessed on 12 May 2012).

- Ho, C.C.; Huang, C.; Ou, C.Y. Analysis of the factors influencing sustainable development in the insurance industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner, B.E.; Payne, D.; Raiborn, C.A. Building values, business ethics and corporate social responsibility into the developing organization. J. Dev. Entrep. 2002, 7, 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.J.; Jones, R.E. Stakeholder mismatching: A theoretical problem in empirical research on corporate social performance. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 1995, 3, 229–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Meins, E. Two dimensions of corporate sustainability assessment: Towards a comprehensive framework. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2013, 21, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Blom, J. The reciprocal and non-linear relationship of sustainability and financial performance. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2011, 20, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, J.; Permatasari, P.; Tilt, C. Sustainable development goal disclosures: Do they support responsible consumption and production? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 118989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.P. Insurers’ impacts remain uncovered. Environ. Financ. 2003, 17, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, M.S.; Muttakin, M.B.; Khan, A. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures in insurance companies. Int. J. Acc. Inf. Manag. 2019, 27, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.U.; Chaudhry, T.; Alam, F.-E.; Ahmad, G. An analytical study of the potential of Takaful companies. Eur. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2010, 20, 54–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.I.; Wang, W.H. Impact of CSR perception on brand image, brand attitude and buying willingness: A study of a global café. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.K.; Jain, R.; Singh, S. An overview of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in insurance sector with special reference to Reliance Life Insurance. World Sci. News 2016, 2, 196–223. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, J.J.; Lee, S. The importance of philanthropic corporate social responsibility and its impact on attitude and behavioral intentions: The moderating role of the barista disability status. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.; Esteban, R. Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2007, 16, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.F.; Samsi, S.Z.M.; Rasit, R.M.; Yunus, N.; Rahim, N.R.A. Corporate social responsibility for Takaful industry’s branding image. J. Pengur. (UKM J. Manag.) 2016, 46, 15–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Manokaran, K.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Hishan, S.; Soehod, K. The impact of corporate social responsibility on financial performance: Evidence from Insurance firms. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 913–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, T.; Jamali, D. Looking inside the black box: The effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2016, 243, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.R.; Eden, L.; Li, D. CSR reputation and firm performance: A dynamic approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Antwi-Adjei, A.; Bawuah, J. A systematic review of the business case for corporate social responsibility and firm performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Chang, J. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance: The mediating role of marketing competence and the moderating role of market environment. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 2, 505–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.E. Environments as moderators of the relationship between strategy and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1986, 29, 329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Nazri, M.A.; Omar, N.A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Takaful Agency’s Business Performance in Malaysia: A Critical Review. In Proceedings of the 2nd Global Conference on Economics and Management Sciences 2016, Langkawi, Malaysia, 28–29 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, H.R.; Johnson, F.E. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; New York Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, I.; Hasnaoui, A. The meaning of corporate social responsibility: The vision of four nations. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lantos, G.P. The ethicality of altruistic corporate social responsibility. J. Consum. Mark. 2002, 19, 205–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures–a theoretical foundation. Acc. Audit. Acc. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, G.F.; Yang, H.T. Does consumer empathy influence consumer responses to strategic corporate social responsibility? The dual mediation of moral identity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmohammadi, C. Impact of corporate social responsibility practices on organizational performance: An ISO 26000 perspective. Soc. Responsib. J. 2014, 10, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, W.; Gao, Y.; Ansett, S.; Xu, S. Can socially responsible leaders drive Chinese firm performance? Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2015, 10, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, P.J.; Devinney, T.M.; Yip, G.S.; Johnson, G. Measuring organizational performance: Towards methodological best practice. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 718–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuei, C.H.; Madu, C.N.; Lin, C. The relationship between supply chain quality management practices and organizational performance. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2001, 18, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N.; Ramanujam, V. Measurement of business performance in strategy research: A comparison of approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Milliman, J.; Lucas, A. Effects of CSR on employee retention via identification and quality-of-work-life. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1163–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enquist, B.; Johnson, M.; Skålén, P. Adoption of corporate social responsibility–incorporating a stakeholder perspective. Qual. Res. Acc. Manag. 2006, 3, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility: A fresh perspective into theory and practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M. Business as a Calling: Work and the Examined Life; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Maon, F.; Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V. Designing and implementing corporate social responsibility: An integrative framework grounded in theory and practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D.; Sen, S. Strengthening stakeholder–company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 2, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O. Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Lee, K.H.; Li, D.-X. The impact of CSR on relationship quality and relationship outcomes: A perspective of service employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zeng, S.; Chen, H. Signaling good by doing good: How does environmental corporate social responsibility affect international expansion? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beurden, P.; Gössling, T. The worth of values—A literature review on the relation between corporate social and financial performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossling, T.; Vocht, C. Social Role Conceptions and CSR Policy Success. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 47, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankoski, L. Corporate responsibility activities and economic performance: A theory of why and how they are connected. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2008, 17, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. The Politics of Stakeholder Theory: Some Future Directions. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzi, A.; Toniolo, S.; Manzardo, A.; Ren, J.; Scipioni, A. Exploring the Direction on the Environmental and Business Performance Relationship at the Firm Level. Lessons from a Literature Review. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, R.M.; Hayibor, S.; Agle, R.B. The Relation between Social and Financial Performance: Repainting a Portrait. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Walsh, J.P. Misery Loves Companies: Rethinking Social Initiatives. Bus. Adm. Sci. Quart. 2003, 48, 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, R.W.; Karim, K.E.; Aleksanyan, M.; Wu, C. An examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and financial performance: The case of Chinese state-owned enterprises. Accounting for the Environment: More Talk and Little Progress. Adv. Environ. Acc. Manag. 2014, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Claver-Cortés, E.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Tarí, J.J. Green management and financial performance: A literature review. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1080–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, M.; Fraser, S. The relationship between corporate social performance and corporate financial performance: Industry type as a boundary condition. Bus. Rev. 2006, 5, 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-H.; Chen, K.-Y.; Chen, S.-C. Total quality management, market orientation and hotel performance: The moderating effects of external environmental factors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R.C.; Stewart, W.H., Jr.; Sweo, R. Environmental scanning behavior in a transitional economy: Evidence from Russia. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 403–427. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois, L.J., III. Strategy and environment: A conceptual integration. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1980, 5, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrogiovanni, J.G. Environmental munificence: A theoretical assessment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 542–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Beard, D.W. Dimensions of organizational task environments. Adm. Sci. Q. 1984, 29, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Fuentes, M.M.; Albacete-Sáez, C.A.; Lloréns-Montes, F.J. The impact of environmental characteristics on TQM principles and organizational performance. Omega 2004, 32, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ventur. 1991, 6, 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Does competitive environment moderate the market orientation-performance relationship? J. Mark. 1994, 58, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.B. Characteristics of organizational environments and perceived environmental uncertainty. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandwalla, P. The Design of Organizations; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Sharfman, M.; Dean, J.W. Conceptualizing and measuring the organizational environment: A multidimensional approach. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 681–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goll, I.; Rasheed, A.A. The moderating effect of environmental munificence and dynamism on the relationship between discretionary social responsibility and firm performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 49, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annuar, H.A. Al-Wakalah and customers’ preferences toward it: A case study of two takaful companies in Malaysia. Am. J. Islamic Soc. Sci. 2004, 1, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, S.; Alsahliy, D.K.; Hishan, S.S.; Keong, L.B.; Vaicondam, Y. Corporate responsibility of the listed Malaysian insurance companies. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 9279–9281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muwazir, M.R.; Muhamad, R.; Noordin, K. Corporate social responsibility disclosure: A Tawhidic approach. J. Syariah 2006, 14, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A. Marketing Research: Methodological Foundations, 5th ed.; The Dryden Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gounaris, S.P.; Avlonitis, G.J. Market orientation development: A comparison of industrial vs consumer goods companies. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2001, 16, 354–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuagwu, L. Market orientation in Nigerian companies. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2006, 24, 608–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooi, L.W.; Ngui, K.S. Enhancing organizational performance of Malaysian SMEs. Int. J. Manpow. 2014, 35, 973–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, F.F.; Hung, K.; Tse, D.K. When does Guanxi matter? Issues of capitalization and its dark sides. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Samat, N.; Lo, M.C. Market orientation, service quality and organizational performance in service organizations in Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2011, 8, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using smartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Vinzi, V.E.; Trinchera, L.; Amato, S. PLS Path Modeling: From Foundations to Recent Developments and Open Issues for Model Assessment and Improvement. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares. Springer Handbooks of Computational Statistics; Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, M.L.; Madueno, J.H.; Martínez-Martínez, D.; Sancho, M.P.L. Competitiveness and environmental performance in Spanish small and medium enterprises: Is there a direct link? J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 101, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Cheah, J.H. Partial least squares structural equation modeling using SmartPLS: A software review. J. Mark. Anal. 2019, 7, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, And Practices, 2nd ed.; University of South Florida: Tampa, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Raut, R.D.; Mangla, S.K.; Narwane, V.S.; Gardas, B.B.; Priyadarshinee, P.; Narkhede, B.E. Linking big data analytics and operational sustainability practices for sustainable business management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Algebra and Statistics; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Chan, F.K.; Thong, J.Y. Designing e-government services: Key service attributes and citizens’ preference structures. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Liu, Z. Institutional background, company value and social responsibility cost: The evidence from listed companies of CSI300 index. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2013, 16, 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.; Ferrell, L. A stakeholder model for implementing social responsibility in marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 956–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).