The Social Metabolism of Quiet Sustainability in the Faroe Islands

Abstract

1. Introduction

Social Metabolism, Biocultural Diversity, and Diverse Practices of Quiet Sustainability

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

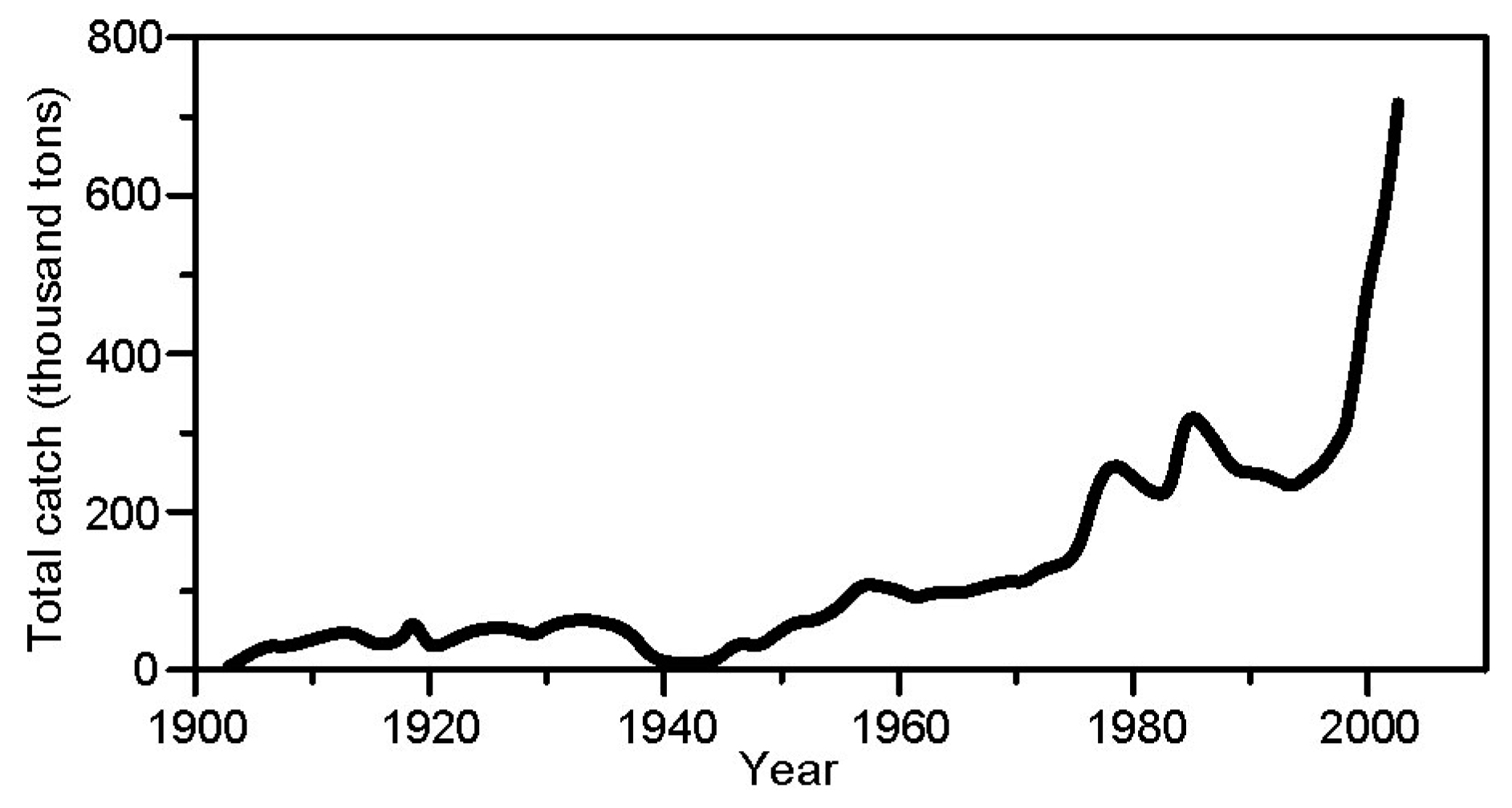

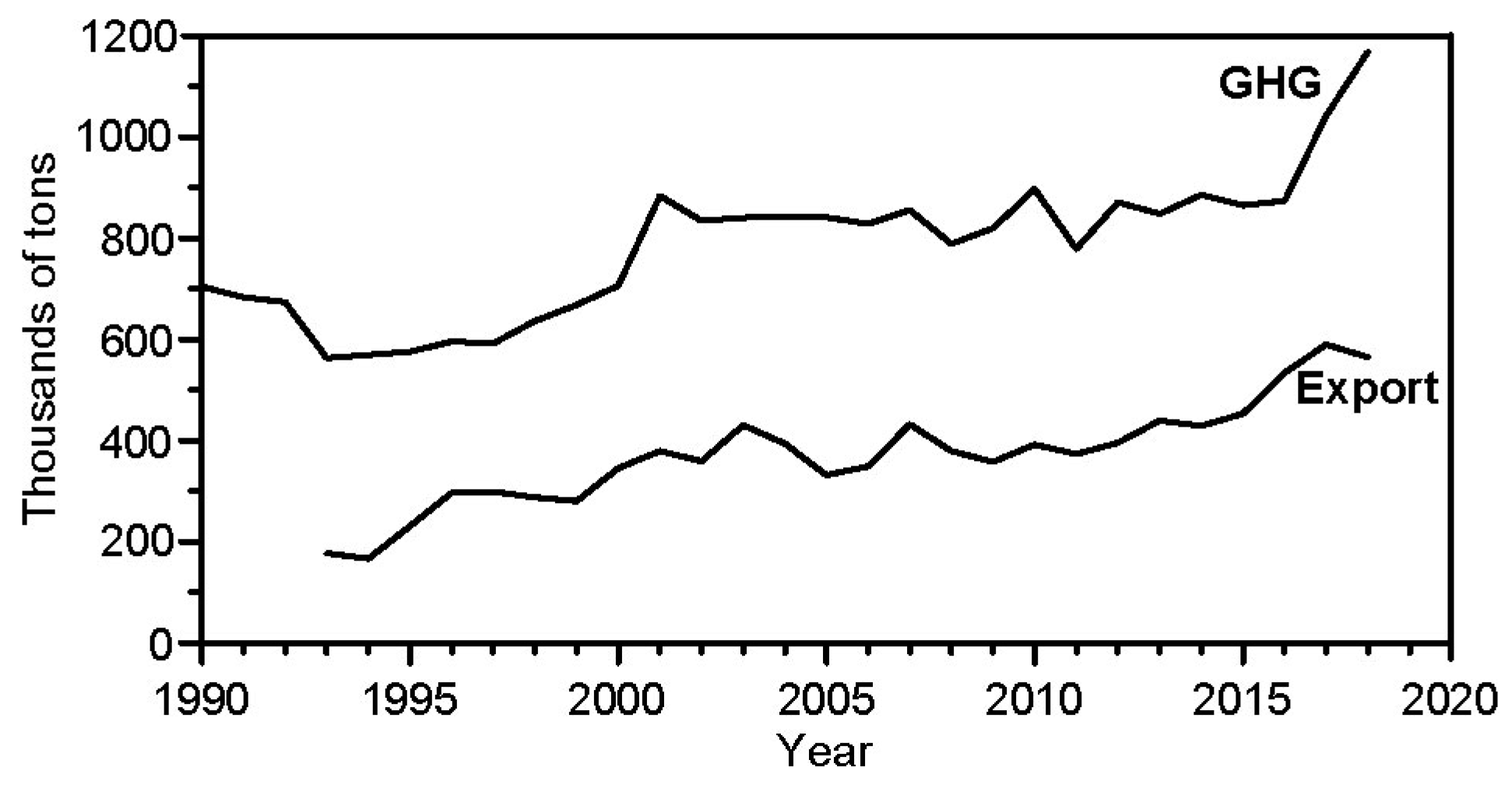

3.1. Industrial and Traditional Social Metabolism on the Faroes

3.2. The Sustainable Roots of Current Faroese Land Use Management Practices

3.3. From an Agrarian to an Industrial Socio-Metabolic Regime

3.4. Quantifying Practices of Quiet Sustainability

3.4.1. Sheep Rearing

3.4.2. Cultivation (Potatoes)

3.4.3. Fowling

3.4.4. Whaling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krausmann, F.; Gingrich, S.; Eisenmenger, N.; Erb, K.-H.; Haberl, H.; Fischer-Kowalski, M. Growth in global material use, GDP and population during the 20th century. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2696–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Broadgate, W.; Deutsch, L.; Gaffney, O.; Ludwig, C. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. Anthr. Rev. 2015, 2, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schandl, H.; Fischer-Kowalski, M.; West, J.; Giljum, S.; Dittrich, M.; Eisenmerger, N.; Geschke, A.; Lieber, M.; Wieland, H.; Schaffartzik, A.; et al. Global Material Flows and Resource Productivity: Forty Years of Evidence. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 22, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, J.R. Something New under the Sun. An Environmental History of the Twentieth Century; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, D.W.; Fanning, A.L.; Lamb, W.F.; Steinberger, J.K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, J.R. Islands of the Mind. How the Human Imagination Created the Atlantic World; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, E. The ballad dance of the Faroese: Island biocultural geography in an age of globalization. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2004, 95, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.; Tsai, H.-M. Islands: Ecologically unequal exchange and landesque capital. In Ecology and Power, Struggles over Land and Material Resources in the Past, Present and Future; Hornborg, A., Clark, B., Hermele, K., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Deschenes, P.J.; Chertow, M. An island approach to industrial ecology: Towards sustainability in the island context. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2004, 47, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausmann, F.; Richter, R.; Eisenmerger, N. Resource Use in Small Island States: Material Flows in Iceland and Trinidad and Tobago, 1961–2008. J. Ind. Ecol. 2014, 18, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.; Fugate, E.; Ashton, W. The intimacy of human-nature interactions in islands. In Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research. Studies in Society-Nature Interactions across Spatial and Temporal Scales; Singh, S.J., Haberl, H., Chertow, M., Mirtl, M., Schmid, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 315–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bogadóttir, R. Blue Growth and its discontents in the Faroe Islands: An island perspective on Blue (De) Growth, sustainability, and environmental justice. Sustain. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowdy, J.M.; McDaniel, C.N. The physical destruction of Nauru: An example of weak sustainability. Land Econ. 1999, 75, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornborg, A. Ecology as semiotics: Outlines of a contextualist paradigm for human ecology. In Nature and Society Anthropological Perspectives; Descola, P., Palsson, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rozzi, R. Biocultural Ethics: From Biocultural Homogenization Toward Biocultural Conservation. In Linking Ecology and Ethics for a Changing World: Values, Philosophy, and Action; Rozzi, R., Pickett, S., Palmer, C., Armesto, J.J., Callicot, J.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Bayo, F.; Wyckhuys, K.A.G. Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 232, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegmon, M. The Give and Take of Sustainability: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives on Tradeoffs; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McMillen, H.L.; Ticktin, T.; Friedlander, A.; Jupiter, S.D.; Thaman, R.; Campbell, J. Samll islands, valuable insights: Systems of customary resource use and resilience to climate change in the Pacific. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, M.; Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Indigenous Knowledge for Biodiversity Conservation. Ambio 1993, 22, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Jehlicka, P. Quiet sustainability: Fertile lessons from Europe’s productive gardeners. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Graham, J.K. Diverse economies: Performative practices for ‘other worlds’. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2008, 32, 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawick, P.; Hornborg, A. Revisiting the Image of Limited Good: On Sustainability, Thermodynamics, and the Illusion of Creating Wealth. Curr. Anthropol. 2015, 56, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakie, P.; Brookfield, H. Land Degradation and Society; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Widgren, M.; Håkansson, N.T. Landesque Capital: What is the Concept Good For? In Landesque Capital. The Historical Ecology of Enduring Landscape Modifications; Håkansson, N.T., Widgren, M., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson, N.T.; Widgren, M. (Eds.) Landesque Capital. The Historical Ecology of Enduring Landscape Modifications; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Winiwarter, V.; Schmid, M.; Haberl, H.; Singh, S.J. Why Legacies Matter: Merits of a Long-Term Perspective. In Social Ecology, Society-Nature Interaction across Space and Time; Haberl, H., Fischer-Kowalski, M., Krausmann, F., Winiwarter, V., Eds.; Springer International: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich, S.; Schmid, M.; Dirnbock, T.; Dullinger, I.; Garstenauer, R.; Gaube, V.; Haberl, H.; Kainz, M.; Kreiner, D.; Mayer, R.; et al. Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research in Practice: Lessons from the Inter- and Transdisciplinary Research in the Austrian Eisenwurzen. Sustainability 2016, 8, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balée, W. Advances in Historical Ecology; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Haberl, H.; Winiwarter, V.; Andersson, K.; Ayres, R.U.; Boone, C.; Castillo, A.; Cunfer, G.; Fischer-Kowalski, M.; Freudenburg, W.R.; Furman, E.; et al. From LTER to LTSER: Conceptualizing the Socioeconomic Dimension of Long-Term Socioecological Research. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González de Molina, M.; Toledo, V.M. The Social Metabolism: A Socio-Ecological Theory of Historical Change; Springer: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haberl, H.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Erb, K.-H.; Görg, C.; Krausmann, F. The Material Stock-Flow-Service Nexus: A New Approach for Tackling the Decoupling Conundrum. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisz, H.; Suh, S.; Graedel, T.E. Industrial Ecology: The role of manufactured capital in sustainability. Proc. Natl. Sci. Acad. USA 2015, 112, 6260–6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Liu, G.; Müller, D.B. Characterizing the role of built environment stocks in human development and emission growth. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 123, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornborg, A.; McNeill, J.R.; Martinez-Alier, J. Rethinking Environmental History: World-System History and Global Environmental Change; Altamira Press: Plymouth, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Widgren, M. Slaves: Inequaliy and sustainable agriculture in pre-colonial West Africa. In Ecology and Power: Struggles over Land and Material Resources in the Past, Present, and Future; Hornborg, A., Clark, B., Hermele, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, J. Is global inequality getting better or worse? A critique of the World Bank’s convergence narrative. Third World Q. 2017, 38, 2208–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, G.; Clark, E. Guest editorial introduction: Islanding cultural geographies. Cult. Geogr. 2013, 20, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornborg, A. How to turn an ocean liner: A proposal for voluntary degrowth by redesigning money for sustainability, justice, and resilience. J. Political Ecol. 2017, 24, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Kowalski, M. Analyzing sustainability transitions as a shift between socio-metabolic regimes. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, H.; Fischer-Kowalski, M.; Krausmann, F.; Martinez-Alier, J.; Winiwarter, V. A socio-metabolic transition towards sustainability? Challenges for another Great Transformation. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, D. Debt the First FiveThousand Years; Melville House: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wengrow, D.; Graeber, D. Farewell to the ‘childhood of man’: Ritual, seasonality, and the origins of inequality. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2015, 21, 597–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House of Industry. 2019. Available online: https://www.industry.fo/international-edition/about-the-faroe-islands/economic-situation (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Fischer-Kowalski, M.; Weizs, H. Society as a hybrid between material and symbolic realms: Toward a theoretical framework of society-nature interaction. Adv. Hum. Ecol. 1999, 8, 215–251. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Kowalski, M.; Haberl, H. Social metabolism: A metrics for biophysical growth and degrowth. In Handbook of Ecological Economics; Martinez-Alier, J., Muradian, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 100–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Trade (Vinnumálastýrið). Álit um Landbúnaðarviðurskifti Føroya; Appointed Committee under the Ministry of Trade: Tórshavn, Faroe Islands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jákupstovu, H. Fiskiskapur við Førpyar í 100 ár; Fiskirannsóknarstovan: Tórshavn, Faroe Islands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- SFI2019. Available online: https://statbank.hagstova.fo/pxweb/en/H2/H2__UH__UH01/uh_uthbolk.px/ (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Eurostat. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Physical_imports_and_exports (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Guillen, J.; Cheilari, A.; Damalas, D.; Barbas, T. Oil for Fish: An Energy Return on Investment Analysis of Selected European Union Fishing Fleets. J. Ind. Ecol. 2016, 20, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment Agency of the Faroe Islands. 2019. Available online: http://www.us.fo/Default.aspx?ID=14068 (accessed on 28 September 2019).

- Environment Agency of the Faroe Islands. 2019. Available online: http://umhvorvisstovan.fo/Default.aspx?ID=14086 (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Environment Agency of the Faroe Islands. 2019. Available online: http://www.us.fo/Default.aspx?ID=14217 (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Eurostat. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Municipal_waste_landfilled,_incinerated,_recycled_and_composted,_EU-28,_1995-2017.png (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Guttesen, R. Animal production and climate variation in the Faeroe Islands in the 19th century. Geogr. Tidsskr. Dan. J. Geogr. 2003, 103, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, S. Faroese Spade-Cultivation, Reinavelta, Its Practice, Function, and History. Fróðskaparrit 1989, 38–39, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Guttesen, R. Veðurlag, framleiðsla, og fólkatal í 1800-talinum og fyrr. In Brot úr Føroya Søgu; Nolsøe, L., Ed.; Fróðskapur: Tórshavn, Faroe Islands, 2010; pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Guttesen, R. Commander Loebner’s tables and vital necessities in the Faeroe Islands in 1813. Geogr. Tidsskr. 1999, 1, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Guttesen, R. Plant production on a Faroese farm 1813–1892, related to climate fluctuations. Geogr. Tidsskr. Dan. J. Geogr. 2001, 101, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttesen, R. Food production, climate and population in the Faeroe Islands 1584–1652. Geogr. Tidsskr. Dan. J. Geogr. 2004, 104, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsson, A. Land Divisions, Land Rights, and Land Ownership in the Faeroe Islands. In Nordic Landscapes: Region and Belonging on the Northern Edge of Europe; Jones, M., Olwig, K.R., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2008; pp. 77–105. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsteinsson, A. Merkur, alin og gyllin—Gomul føroysk virðismeting. Frøði 1993, 1, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Church, M.J.; Arge, S.V.; Brewington, S.; McGovern, T.H.; Woollett, J.M.; Perdikaris, S.; Lawson, I.T.; Cook, G.T.; Amundsen, C.; Harrison, R.; et al. Puffins, Pigs, Cod and Barley: Paleoeconomy at Undir Junkarinsfløtti, Sandoy, Faroe Islands. Environ. Archaeol. 2005, 10, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, D.L. The Stratigraphical Cultural Landscape. In Outland Use in Preindustrial Europe; Anderson, H., Ersgård, L., Svensson, E., Eds.; Lund Studies in Medieval Archaeology 20; Institute of Archaeology, University of Lund: Lund, Sweden, 1998; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, I.T.; Church, M.J.; McGovern, T.H.; Arge, S.V.; Wollett, J.; Edwards, K.J.; Gathorne-Hardy, J.; Dugmore, A.J.; Cook, G.; Mairs, K.-A.; et al. Historical Ecology on Sandoy, Faroe Islands: Palaeoenvironmental and Archaeological Perspectives. Hum. Ecol. 2005, 33, 651–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Brewington, S. Tradeoffs and Human Well-Being: Achieving Sustainability in the Faroe Islands. In The Give and Take of Sustainability. Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives on Tradeoffs; Hegmon, M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 222–243. [Google Scholar]

- Isholm, E. Eplaskipið 1840—Tá tað almenna fór at keypa eplir. Frøði 2014, 3, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Isholm, E. Fiskivinna sum Broytingaramboð hjá Amtmanninum. Ph.D. Thesis, Fróðskaparsetur Føroya, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands, 8 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel, S.; Isendahl, C. Urban gardens, agriculture, and water management: Sources of resilience for long-term food security in cities. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B.; Chappell, M.J.; Vandermeer, J.; Smith, G.; Quintero, E.; Benzner-Kerr, R.; Griffith, D.M.; Ketcham, S.; Latta, S.C.; McMichael, P.; et al. Effects of industrial agriculture on climate change and the mitigation potential of small-scale agro-ecological farms. CAB Rev. Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2011, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SFI2019. Available online: https://statbank.hagstova.fo/pxweb/en/H2/H2__MT__MT08__MT0802/MT306.px/ (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Austrheim, G.; Asheim, L.J.; Bjarnason, G.; Feilberg, J.; Fosaa, A.M.; Holand, Ø.; Høegh, K.; Jonsdottir, I.S.; Magnússon, B.; Mortensen, L.E.; et al. Sheep grazing in the North Atlantic region: A long term perspective on management, resource economy and ecology. Rapport Zoologisk Serie 2008, 3, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, L.C.; Austrheim, G.; Asheim, L.J.; Bjarnason, G.; Feilberg, J.; Fosaa, A.M.; Hester, A.J.; Holand, Ø.; Jónsdóttir, I.S.; Mortensen, L.E.; et al. Sheep grazing in the North Atlantic region: A long-term perspective on environmental sustainability. Ambio 2016, 45, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González de Molina, M.; Soto Fernández, D.; Infante-Amate, J.; Aguilera, E.; Vila Traver, J.; Guzmán, G.I. Decoupling Food from Land: The Evolution of Spanish Agriculture from 1960 to 2010. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randbøll Wolff, M. Belysning af de Konkurrencemæssige Vilkår, Som Færøsk Landbrug er Konfronteret Med fra Importerede Landbrugs-og Fødevarer, Særlig fra Overføringsstøttet Produktion i EU og EØS. En Rapport Udarbejdet på Opdrag af Búnaðarstovan 2016. Available online: http://www.bst.fo/Admin/Public/DWSDownload.aspx?File=%2fFiles%2fFiler%2fBunadarstovan%2fBelysning+af+de+konkurrencem%c3%a6ssige+vilk%c3%a5r+for+f%c3%a6r%c3%b8sk+landbrug_M_R_Wolff_juni+2016.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Olsen, B. (Havstovan, Faroe Marine Research Institute, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands). Personal communication, 11 October 2019.

- Bloch, D.; Zachariassen, M. The “skinn” values of Faroe Islands pilot whales: An evaluation and corrective proposal. JN Atl. Stud. 1989, 1, 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sans, P.; Combris, P. World meat consumption patterns: An overview of the last fifty years (1961–2011). Meat Sci. 2015, 109, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhoek, H.; Lesschen, J.P.; Rood, T.; Wagner, S.; De Marco, A.; Murphy-Bokern, D.; Leip, A.; Van Grinsven, H.; Sutton, M.A.; Oenema, O. Food choices, health and environment: Effects of cutting Europe’s meat and dairy intake. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridis, P.; Huber, J. A Socio-metabolic Transition of Diets on a Greek Island: Evidence of “Quiet Sustainability”. In Socio-Metabolic Perspectives on the Sustainability of Local Food Systems; Frankova, E., Haas, W., Singh, S.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 7, pp. 263–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hornborg, A.; Eriksen, L.; Bogadóttir, R. Correlating Landesque Capital and Ethno-Political Integration in Pre-Columbian South America. In Landesque Capital: The Historical Ecology of Enduring Landscape Modifications; Håkansson, N.T., Widgren, M., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Widgren, M. Precolonial Landesque Capital: A Global Perspective. In Rethinking Environmental History: World-System History and Global Environmental Change; Hornborg, A., McNeill, J.R., Martinez-Alier, J., Eds.; Rowman Altamira: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss-Smith, T. From Taro Garden to Golf Course? Alternative Futures for Agricultural Capital in the Pacific Islands. In Environment and Development in the Pacific Islands; Burt, B., Clerk, C., Eds.; National Centre for Development Studies, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, the Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 1997; pp. 143–170. [Google Scholar]

- Tello, E.; González de Molina, M. Methodological Challenges and General Criteria for Assessing and Designing Local Sustainable Agri-Food Systems: A Socio-Ecological Approach at Landscape Level. In Socio-Metabolic Perspectives on the Sustainability of Local Food Systems; Frankova, E., Haas, W., Singh, S.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 7, pp. 27–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bogadóttir, R.; Olsen, E.S. Making degrowth locally meaningful: The case of the Faroese grindadráp. J. Political Ecol. 2017, 24, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Faroe Isl. | EU | World |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population density (people/km2) | 36 | 118 | 51 |

| CO2 emission per capita (tons CO2/year) | 20 | 7 | 5 |

| Waste generation per capita (kg/day) | 2.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Food Category | Total Amount 1 | Per Capita |

|---|---|---|

| Sheep | 900 tons | 18 kg |

| Potatoes | 700 tons | 14 kg |

| Sea bird | 70 tons | 1.4 kg |

| Whale meat | 186 tons | 3.6 kg |

| Whale blubber | 167 tons | 3.3 kg |

| Total | 2023 tons | 40.3 kg |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bogadóttir, R. The Social Metabolism of Quiet Sustainability in the Faroe Islands. Sustainability 2020, 12, 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020735

Bogadóttir R. The Social Metabolism of Quiet Sustainability in the Faroe Islands. Sustainability. 2020; 12(2):735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020735

Chicago/Turabian StyleBogadóttir, Ragnheiður. 2020. "The Social Metabolism of Quiet Sustainability in the Faroe Islands" Sustainability 12, no. 2: 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020735

APA StyleBogadóttir, R. (2020). The Social Metabolism of Quiet Sustainability in the Faroe Islands. Sustainability, 12(2), 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020735