Abstract

(1) Background: There is a global trend to stimulate sustainable urbanization by updating the hardware of the built environment with green technologies. However, simply greening the city hardware does not ensure a sustainable urban system. In reality, urban communities, as cells of the city, play a crucial role in the sustainable development of the entire city. (2) Methods: This paper conducts a case study by investigating a community in Taipei with semi-structured interviews and other first-hand data. It examines how self-organization, voluntary groups, and the public participation of community members has successfully institutionalized a governing system for the sustainable development of communities; (3) Results: This paper identifies the major actors and mechanisms underpinning the sustainable development of urban communities with a case study in Taipei. The establishment of this more cost-effective form of community governance will possibly provide more benefits to community members; (4) Conclusions: This case study will shed light on the sustainable development of urban community in many other cities, offering possible pathways and epitome for self-organization of urban community in the coming era. Its cost-effective institutional design contributes greatly to sustainable community development, partly solving the current failure to promote urban sustainability.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development has become a major global theme in response to the continued deteriorating environmental conditions in recent decades, engendering constant innovations in policy instruments, green technologies, and industrial models. These innovations have occurred in multiple waves to stimulate sustainability, ranging from international cooperation to local governance, and from advocating greener production models to enhancing people’s awareness of the need for sustainability [1]. In developing countries such as China, a massive sustainability campaign has accompanied rapid urbanization, which has also given rise to the construction of conceptual towns and cities (e.g., eco-cities and low-carbon cities) [2,3]. However, it seems likely that a large proportion of these projects will not only fail to fulfill their sustainable promises but also that the tremendous input of resources involved makes them actually good examples of anti-sustainability development models [4]. While sustainability at the micro level is the key and very foundation of sustainable development, many projects simply provide new and greener city infrastructure, leaving local community governance and its members’ way-of-life unchanged [2]. Sustainability at the community level, therefore, is vital to the realization of sustainable development.

This paper reports on an intensive investigation into the community governance of Zhongshun Li, an urban community in Taipei. This involved interviewing the community leaders and participants of volunteer groups as well as local residents. Together with the analysis of government statistics, documents, and other materials, we argue that suitably arranged public participation plays a crucial role in the self-governance of the community and helps to realize sustainable development within the community at a comparatively low cost. In the following section, we examine the interaction mechanisms and major players in the local community governance of Zhongshun Li, focusing on the role of key leaders and voluntary groups. The detailed case study follows this framework in Section 3 and a discussion in Section 4. The final section contains some concluding remarks on the implications for local governance of sustainable development at the community level.

1.1. Sustainability at the Community Level

Sustainability is too broad a concept and would lose its foci without a proper definition in discussion. Mischen et al. gave a very clear and comprehensive definition of sustainability at the community level. They defined a sustainable community as one in which individuals and organizations are “functionally and socially connected” to provide various services to improve the heath, educational conditions, and other material and spiritual well-being of community members through self-determination with shared collective resources in the community [4].

Sustainability at the community level relies heavily on a robust mechanism for allocating local resources and delivering services at a comparatively low cost [5,6]. The state and market, and the combination of the two, are the most important means of resource allocation and service delivery, in which the former stresses universality and equity with stronger government intervention and the latter highlights efficiency with an unrestrictive attitude towards the private sector [7,8]. Nevertheless, communities have attributes that are neither suited to direct governance by the government nor the market because the residents in the same community constantly interact and are incentivized by a blend of economic self-interest and altruism for the community as a commonwealth [7,9,10]. Therefore, if the mode of governance incorrectly designed, the market or state can easily become dominant at the community level, which is not enough to serve needs of the communities. Moreover, local governance can be many times more costly and less effective without suitable self-organization and public involvement [11,12,13,14]. Thus, it is important to determine the community governance models that best support sustainability at the micro level. When confronted with many costly failures, as is especially the case in China, this is a matter of some urgency.

1.2. Characteristics of Community Governance

As mentioned earlier, governance at the community level is distinctly different to the conventional mechanism of state or market. The three types of governance, namely the state (a system of command), the market (voluntary exchange), and community governance (cooperation) are rarely mutually exclusive [15]. However, the demands at the community level are so complex and subtle that a particular institutional arrangement is needed to leave enough room for cooperation between the community members themselves. According to Bowles and Gintis [7], for example, community governance is “the set of small group social interactions that, with market and state, determine economic outcomes”, which is relevant to the both the selfishness and altruism of human nature and the social capital of the community. The distinctive traits of communities also demand a particular type of institutional arrangement to fit local conditions [16,17]. However, one common feature of all well-functioning community governance institutions is the maintenance of constant and reciprocal cooperation between community members, which will provide the most cost-effective means for sustainable development within the community [5,18,19].

1.3. Intuitionalist Perspectives

Elinor Ostrom is the leading scholar in analyzing cooperative governing institutions at the community level. She has developed an institutional analysis framework to explain why the institutional arrangements of a community is constituted in certain ways and how the outcomes of its performance will, in turn, adjust and reshape the institution itself [10,20,21,22]. She argues that the rules in use, the material conditions and the attributes of the community together are the exogenous factors that influence the institutions of the community and the actions of the participants involved. The outcome of the actions also constantly modify the institutions within the communities. In addition, she also summarizes seven features of community institutions that successfully maintain sustainable and cost-effective governance (see Table 1). To be more specific, all well-functioning institutions at the community levels require, first, a clear distinction between insiders and outsiders. Local conditions tailor the institutions and public opinions provided through proper channels to the decision-making arena, and finally, enough room should be left for local discretion in case the demands from the government or business interests ruin the self-organized institutions.

Table 1.

Design principles for sustainable and cost-effective community governance institutions [22].

1.4. Public Participation and Voluntary Groups

In effect, the sustainable development of urban communities requires a sustained interacting mechanism between social capital, urban space and natural capital, which depends on efficient mobilization of citizens and the local governing institutions. To mobilize and integrate community members’ participation into local governing system is crucial to the balance between social capital, natural capital and constraint urban space. And community voluntary groups are the most representative approach for the mobilization of local residents. Several studies conclude that voluntary groups are the key to public participation. Research into community health service delivery indicates that voluntary groups boost public participation and improve community service quality [23,24,25,26]. Another terrain of literature shows that voluntary groups are crucial in linking public participation and local administration, concluding that voluntary teams and the active participants in these groups necessarily link the administration with the general public, channeling personnel, opinions, and resources to flow within the institutions [27,28,29]. However, in the Chinese context where community governance is more bureaucratic, the voluntary groups to a large extent, are co-opted into the government institutions. This institutional cost of this system is rather high while its performance in local community governance is comparatively low [16,17,30,31]. In general, current literature on community participation and voluntary groups fails to coping with the mobilization of citizens within this comprehensive framework.

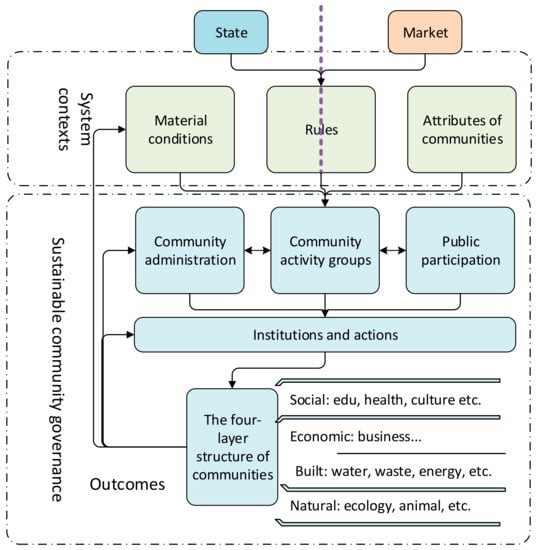

In sum, there are major gaps in current research on sustainable urban community urban development. The arguments from institutionalist perspectives, represented by Ostrom alone is insufficient to explain the mechanism that underpins a sustainable community. First, Ostrom’s research mainly focuses on the use of a common pool of resources, resource allocation, and management issues [20,32,33]. However, a sustainable community is a multi-faceted concept that covers not only resource management but also a myriad of service delivery and cooperative interactions between community members. A sustainable development of urban communities depends on the coordination between natural and social capital in the restraint urban space, covering various economic and social activities in the community (see the bottom part in Figure 1) [34,35,36]. Consequently, the institutional analysis should include the delivery of all these services together with the self-organized management of resources. In like vein, Ostrom’s discussion on public participation is insufficiently comprehensive in her case studies, which pivot on the resources issue too. As sustainability at the community level is a very complicated concept with multiple layers, it also needs to specify how different realms of community life involve public participation; in what way is the participation realized and how it influences the performance of the institutions.

Figure 1.

An integrated analytical framework of sustainable community governance.

2. Materials and Methods

The authors paid 4 field visits to Taipei in 2016 and found that Zhongshun Li is an urban community where the residents are actively involved in the self-governance of their community, with most public services delivered in an efficient manner. Zhongshun Li (Li is a typical name for a Chinese village/community) prevails over its peers in contriving its own community governance institution. Communities in Taiwan, although under a democratic backdrop, also share many historical, cultural, and institutional similarities with those of the mainland, hence providing valuable experience for mainland communities. In this sense, the experience from Zhongshun Li will be an epitome for the community governance transition taking place in the big cities now. The rationale for case selection is explained in details in the following section of case profiles. In our field trips, we have made 23 interviews with the community leader, voluntary group leaders, participants and ordinary community residents. The interviewees were chosen both for purpose and convenience. Since we need to collect information following the analytical framework we contacted key persons who were responsible for the local social and volunteer groups. After we built our connections to the first group of interviewees, we adopted the snowball sampling method to expand the targets for interviews. We also collected information from the ordinary residents in the urban community and as a result, we employed convenience sampling to seek interviewees for our semi-structured interviews for residents. We have also collected data from local community reports, government statistics and other online information. The themes and resources of data is summarized in the following Table 2. These materials enable the authors to conduct an in-depth case study of sustainable community development from the perspective of self-organization and public participation. All the themes were collected and coded following the analytical framework in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Major themes and sources of data.

Reframing Urban Community Governance

As a result, we propose a more integrated theoretical framework in Figure 1 to explain how institutional design contributes to the sustainable development of a community. State and market act as two exogenous variables of the community institutions. These contextual attributes restrict the rules and potential institutions in the community. Moreover, public participation and cooperation among the members themselves is significant in promoting sustainable development at this level, hence reducing institutional costs and promoting the efficiency of the system. In addition, as community sustainability is a multi-faceted concept encompassing many realms and requiring many forms of public service delivery, various voluntary groups play a crucial role in the circulation of personnel, resources, and opinions around the institution. These groups are also necessary for mobilizing public participation and linking the public with the community administration. In turn, the outcomes of these actions reshape and adjust the community institutions to make them more responsive to the actual needs of the members. The case study in Taipei vividly illustrates the key factors of an appropriately designed institution and how they have achieved sustainable development in their community.

We incorporated the collaborated governance framework into the institutional perspectives as discussed in the previous section [37]. In the data collection process, we focus on major themes including the system contexts of the case, such as the resources and institutional conditions, the relations and networks, the economic, social, and cultural conditions of the individuals and organizations in the community. We also zoomed into the drivers and benefits of participants in local community activities as well as the interdependence among different people and groups. The relationship between the community administration, various voluntary groups and the general public in the community is one of the most important features in our analysis. And we collected data on how the community services in social, economic and other aspects are provided with shared community resources.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Profiles of the Case

Zhongshun Li is a typical urban community in Wenshan district, Taipei. Figure 2 shows its location. It occupies a moderate residential area circumvented by schools, parks, and other urban commercial facilities, and with a boundary of around 1.8 km. It is occupied by 1611 typical local households as revealed in the report of the Zhongshun Community Development Association [38]. It is a self-organized association by the local residents that replaces the local government and acts as the local administrative body that interacts with both higher government bodies. It is also the provider of various community service. There is an art college campus within the community that potentially benefits the community’s cultural activities. The famous National Chengchi University is immediately across the river and is often invited to the educational and cultural events of the community. Most of the school age children in the community are enrolled in one primary school and two high schools bordering the community enroll and are frequently involved in community activities as well.

Figure 2.

Location of Zhongshun Li.

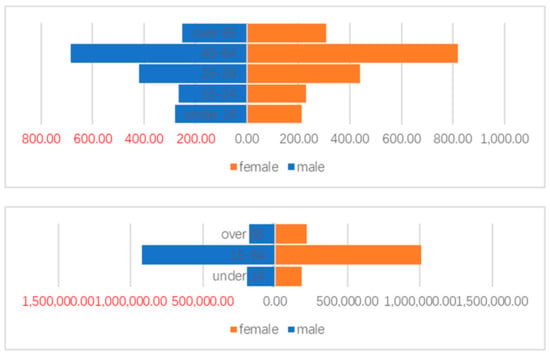

In addition to its geographic features, the demographic traits of the community are also representative of the whole Taipei population in terms of sex ratio and age structure. Figure 3 compares the demographic characteristics of Zhongshun Li and overall Taipei in 2015. The overall population of Zhongshun Li in 2015 was 3906 with 1897 males and 2009 females. The sex ratio of different age groups of the community is almost the same as Taipei. There are five age groups in the Zhongshun Li statistics, but only three in the Taipei survey, and therefore Zhongshun Li has three groups for comparison (Figure 3). This reveals the age ratio to be the same as Taipei with 13% aged under 14 and 14% over 65.

Figure 3.

Population composition of Zhongshun Li (top) and overall Taipei (bottom) in 2015. Sources: Department of Budget, Accounting, and Statistics, Taipei City Government; Wenshan District Office [39,40].

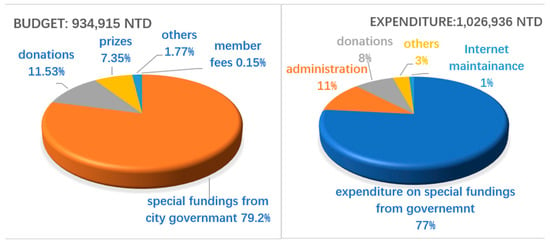

In addition, the financial structures of Zhongshun Li also resemble those of other regions in Taipei and even with ordinary communities in mainland China. With the traditional dependence on a bureaucratic administration, the finance of both the mainland and Taiwan local communities both rely heavily on direct government funding, which usually constitutes 80–90% of the total community budget [41]. Figure 4 shows the budget and expenditure components in 2015. Extraordinarily, Zhongshun Li received a large donation in 2015, accounting for 11.53% of the total budget, considerably reducing the proportion of government funding from its usual 85% in recent years. The private sectors, non-governmental organizations and personal sponsors are seldom involved in providing financial support for the local governance, which raises the question of how, with such heavy dependence on government funding, the community successfully maintains self-governance and public participation.

Figure 4.

Funding budget and expenditure structure of Zhongshun Li in 2015. Sources: Community development Association of Zhongshun, Wenshan District. http://www.chungshun.org.tw/20160606154200).

To sum briefly, Zhongshun Li is a typical community regarding its geographic, demographic, and financial characteristics. Against the background of similar historical and cultural values, the investigation into the underlying elements of its institutions is meaningful for other communities in Taiwan and mainland China.

3.2. How Do Self-Governance and Public Participation Lead to a More Sustainable Zhongshun Community?

As explained in the theoretical framework in Section 2, the major parties involved in the community’s governance include exogenous players (in this case, the government at a higher level and the bureaucratic leaning of local governance), the community administration, voluntary groups, and the public in general. These participants interact to serve one purpose: providing social, cultural and other required services to the community in a cost-effective and sustainable way, and therefore contributing to the common benefits of the community as a whole. The community administration is often at the center of actions, linking the community to the hierarchy government and initiating the local agenda.

3.2.1. The Community Administration

Zhongshun Li’s local administration is its community development association (CDA), a self-organized group first advocated in 1992 by Zeng Ningyi, a community member then and now the community leader. It should be made clear here that although some of the communities in Taiwan face the competition between the CDA and the Li Chief, who is elected by popular vote and is comparatively free from the check of district government. It is not the case in Zhongshun Li. Ms. Zeng has been actively engaged in the election of the community and has been the chief of the community since then. This is also the case for some other communities in Taiwan, where the Li chief also chairs the CDA. In such cases, there usually will be less competition and more cooperation. And it is exactly the case for the urban communities in Mainland China where the local management duty nestles in one entity. The CDA was a brand-new concept to organize the local governing bodies voluntarily by the residents themselves in the early 1990s and, even now, only very few communities in China have managed to organize self-governing bodies of their own [42,43]. According to Ostrom’s theory, one obvious merit of such institutions is that the self-organized body tends to naturally draw a clear demarcation between insiders and outsiders and will gradually nurture a sense of commonwealth based on the mutual interests of community members [22,44]. In these circumstances, the members are more likely to become engaged in community activities and undertake their duties while monitoring the behavior of others. The frequent interactions among residents, who may also be members of the CDA, tend to inspire altruistic actions, as they believe they will contribute to the commonwealth of the community as a whole.

“When I first initiated the proposal for the association, I was just thinking that sometimes the community office didn’t know what we really need and I think all the members should give their own share to the community, to view it as our own home”, said Zeng, the leader. “I am very happy now many people think that they are part of the association and we have a very stable membership throughout the years”, she remarks.

A husband also comments on the association after his family moved into the community three years ago as:

“You know I am very busy with my work so we seldom joined in community activities before we moved here. I did not join the association myself but my neighbors are members and my wife joined one of the volunteer groups. It’s meaningful; basically, I think we run the community by ourselves”.

This resonates with other interviewees directly or indirectly related to the association and those who have a higher level of concern for community affairs, and the people interviewed expressed their happiness in participating in community activities. There are annual elections for positions in the association. However, the process is not competitive as community members have a consensus that those with seniority and enthusiasm in community affairs will better serve the interests of the community as a whole. Moreover, the activists in the associations and other voluntary service groups usually win the favor of the public and thus have a better chance of election. In general, the election is cooperative, rather than competitive. Also worthy of mention is that females, including the leader Zeng, comprise over two-thirds the association members, probably due to the more time they can spend in the community. In this sense, the institution of self-governance helps to strengthen the “insider” identity of members and promote an atmosphere for their mutual benefit. Consequently, members are more willing to participate, contribute, and expressly serve the potential benefits of the members better.

3.2.2. Voluntary Groups and Public Services

However, compared to the population of the whole community, the association is too small to offer many kinds of services. Ostrom has examined the ability of some self-organized institutions to manage community common pool resources, but the public services required in an urban community are much more complex than a single resource management system. A sustainable community at least requires services in four layers (natural, built, economic, and social aspects of community life as illustrated in Figure 1). The management and services required in Zhongshun Li also cover four realms as illustrated in Figure 5. Sustainable management of the community, unlike that of the common pool resources, depends much more on complicated self-organized institutions to operate various aspects of community services. Figure 5 illustrates that the requirements for community sustainability rest upon a multi-layer interwoven task, which is summarized from the various routine documents and interviews in the research. These are not exactly the same as the four layers of sustainable community framework we proposed in Figure 1, but often overlap with each other and one service might contribute to more than one dimension of community sustainability. In Zhongshun Li, the voluntary groups have been playing very important roles in the delivering all these kinds of services in a cost-effective way.

Figure 5.

The management system and participants of different kinds of community services.

Community security is one of the social tasks of community development and requires cooperation between various parties. Various city/district government departments, including the local police station, fire station, and anti-domestic violence center, are involved in the task. Nonetheless, without an appropriately designed mechanism, the process will be costly and the outcomes would probably be less preferable. The voluntary group, namely the assistance and guard team in the Zhongshun case, bridges this gap. The members of the team patrol in pairs on the roads to nearby schools during school hours. The team also talks with shopkeepers and residents along the road, who are neighbors, to check any extraordinary events and pay regular visits to households needing help. It is almost impossible for the police to collect the same information for the same of effort and cost. There are around 150 team members in total, some of whose children or grandchildren attend surrounding schools. The patrol has to take shifts and make records every day. The picture on the left in Figure 6 shows an example of a handwritten patrol record.

Figure 6.

From left to right: the patrol record of the assistance and guard team; a mosaic lane paved by community members and the community farm.

Of course, it is possible that security is the most basic service demanded and other services are less likely fulfill simply with resources from within the community itself. However, other examples occur in the services related to community landscape and cultural events, which requires professional knowledge. Greening and landscape design, for instance, is usually the duty of the district government or outsourced to professional companies. Zhongshun Li, however, uses the tasks involved as opportunities for collective participation and community team building, thus initiating a voluntary group (the members are temporary and new members constantly join in) to take the responsibility for the landscape design and greening in the community. The picture in the middle in Figure 6 shows a lane with an animal mosaic designed and paved by the community members themselves. The animal figures come from the thoughts of students and parents while the merits of other more professional work, for instance, the paintings on the wall, belong to the artistic talents of the students from the community’s art school.

As one community member commented, “I helped design the patterns and it took us weeks to finish this project. The neighbors like it. We turned the dirty back lane into a beautiful road and we no longer worry about the safety of school children now when they go across this lane after school.”

Actually, the community invited the students from nearby high schools and universities several times to draw wall paintings. On the one hand, it saves the community budget for other activities while, on the other, it offers opportunities for social practice/community services that are often encouraged by high schools and universities.

Other activities such as educational/health lectures and classes are also organized by voluntary groups and often attract a constant and stable audience in the community. The experts they invite are not only from official links, but also from the personal connections of the community members themselves. The various voluntary groups are therefore more efficient than formal government bodies in delivering different kinds of services to the residents and these activities are better tailored to their needs, as they are also community members. Yet one question remains unanswered: why are people attracted to such voluntary groups with only a meager payment? Altruism and contribution to the commonwealth of the community alone seem unlikely answers.

3.2.3. Public Participation and a Positive Cycle of Interactions

Effectively mobilizing residents to take part in voluntary groups and community activities is due to the self-organized governing structure of the community, including the CDA, where the atmosphere of participation and engagement is more intense than in other communities. However, most people interviewed share a similar experience in their volunteer careers, that is, they directly benefit from the activities organized by the voluntary groups at the beginning. When they have become frequent participants, they are more likely to join the voluntary group to provide services to a greater audience, making such services sustainable in the long term.

The association has reclaimed small patches of wasteland in the community for farmland to grow vegetables, also a common practice in mainland China. All community members are eligible to claim one patch of land (shown on the right of Figure 6) with a nametag on it. In the following year, that person is responsible for cultivation, while harvesting is by both the person and the community. The CDA voluntary group first made the reclamation in Zhongshun Li, from whence the claims have smoothly rotated annually between members—the system simply running by public participation alone. Those who have participated in the past are likely to help administer the system in the future.

“I got my patch of land two years ago. Actually, it’s not only about growing your own vegetables. It’s more about sharing your time with neighbors and we had a lot of fun when we did the farm work together. This year as there are many people claiming the patches, I helped with the lot-drawing”, a housewife remarked. “I didn’t feel it’s a duty. As I have cultivated my land for a year, I would like to do a favor to my neighbors to help the rules go on”, she replied when asked why she helped with the allocation of farmland.

Another current farmland holder expressed a similar tone:

“We eat the vegetables at our home and also sell them to the community. It’s totally green and organic. The farm work is not laborious. I simply take it as a kind of exercise. As I can’t hold the land next year, I have persuaded my neighbor to join”.

The current participants are likely to sustain the institution in the future. Similar situations occur in many other voluntary activities. Child–parent activity is also a case in point. As shown in the demographic statistics, there are many school-age children in the community. The CDA sponsor a voluntary group to organize a tutorial workshop for the high school students in the community, inviting teachers from nearby schools and universities. They also constantly organize parent–child camps with art skills, sports, and family-bonding themes, which are very popular among the households with school age children. “Once I made a piece of artwork with my parents and now you can still see it in the community center”, a student said, “I enjoy the time with parents and friends”, his father adding, “It’s important to spend time with your children. I believe it’s even better to do it with your neighbors as they are the children’s peers, they would enjoy it more”. The activities advocated by the voluntary groups bring real benefits to the residents and, as a result, even when the students grow up and the household leaves parent–child activities, new members constantly arrive. Public participation is therefore self-sustained and spread around by the members themselves.

Furthermore, the participants who benefit from these activities will probably join the voluntary groups; some will even run for fixed positions in the CDA in the future. “I would like the parent–child activity to go on and I have started to help the association to do some work related to parent–child activities”. A teacher agrees with this mother’s statement, also another local household mother in saying “I will invite my colleagues to join this event and I think it will benefit many families in the community, including mine”. Constant public participation has been bringing fresh blood into the system. By the same token, the interactions between the public and voluntary groups have opened up a channel for personnel, resources, and opinions to flow between the three parties (CDA, voluntary groups, and the public), supporting the sustainable development of the community. The same mechanisms also appear in such other aspects of social services as community elderly care and health services, which is why community members are willing to engage in voluntary activities as both service providers and objects.

4. Discussion

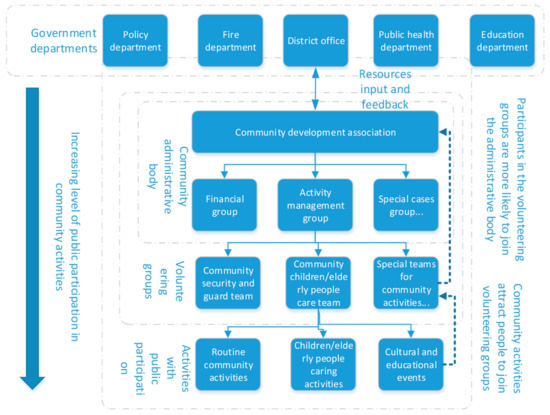

Zhongshun Li exemplifies how bottom-up mobilization of community residents contributes to the sustainable development of a community. However, self-governance, along with positive interactions with the public, is just one potential approach to promoting community sustainability; it is not the only solution to development in cities. However, as the most fundamental building block, sustainable development at the community level can contribute substantially to urban sustainability. The institution of Zhongshun Li has attested to the feasibility of self-governance at the local level and provides experience for other communities in China and other Asian countries, where community governance is still heavily bureaucratic. Self-governance and increased public participation may reduce governance failures in urban communities. Figure 7 provides an institutional model to illustrate how the interactions between the various parties render self-governance effective and sustainable in Zhongshun Li, with local governance divided into three layers with greater public participation.

Figure 7.

Community resources and management structures in Zhongshun Li.

Firstly, the hierarchy government is not well-tuned to the needs of the community and its various members, and consequently the services delivered from the various government departments often mismatches resources to demands. In Zhongshun, the government is not directly involved in local administration. Instead, resource allocation is through the CDA, which is a self-organized group. Self-organization provides a more effective means of clarifying the boundary between insiders and outsiders and tends to naturally bond community members together as members of a commonwealth, where mutually beneficial cooperation is easier to achieve [13]. In contrast, the members in a bureaucratically managed community are more vertically related to the local administration than horizontally related with each other, pushing up the cost of institutions. As indicated by Ostrom, minimum space is left to the discretion of the community when there is government or market intervention [22].

Secondly, the CDA does not directly provide most of the services needed by community members by itself, but through various standing or temporary voluntary groups. Since the sustainable development of the community requires services in all four aspects (natural, built, economic, and social) perfectly tailored to the attributes of the community, voluntary groups are much more sensitive than other public or private bodies. Moreover, voluntary groups are more capable of mobilizing the public to become engaged in public services and other activities, amplifying the effects of the policy and spreading it to a greater audience. Such voluntary groups, however, do not currently exist in most mainland urban communities and, as a result, public participation in most cases is rare and inefficient. These groups also provide a means for activists to move from the bottom to the top of the institution (see the arrows on the right part of Figure 7), that is, those who are more enthusiastic in public affairs may first be ordinary participants, then become service providers in the voluntary groups and finally go to the CDA. It is also a very important channel for opinions, resources, and personnel to flow smoothly within the CDA.

Finally, the active participation of the public, which is often only promoted by neighbors, friends and family members, but also aroused by their own family needs (parent–child activities, elderly people care, health care, etc.), constantly fuels the institution’s continuation. As shown by the interviews, most activists in the voluntary groups and CDA are at first beneficiaries of the community activities. The prevailing participation expands the target audience of the services and further strengthens the bonds within the community, consolidating the idea of the community as a commonwealth. This not only provides human resources for the upper layers of the institution, but also the very means for the delivery of various kinds of services. For instance, it is public participation that realizes the four aspects of services demanded in Zhongshun Li (Figure 5), which is perhaps the most cost-effective approach. Therefore, the institution of self-governance becomes a closed loop providing services down to the public while personnel, resources, and opinions return up smoothly.

5. Conclusions

Zhongshun Li’s self-governance provides valuable experience for the sustainable development of communities, particularly for the emerging self-governing communities where community governance has been transferring from bureaucratic to democratic. This case will definitely shed light on the sustainable development of urban community in many other cities, offering possible pathways and epitome for self-organization of urban community in the coming era. Its cost-effective institutional design contributes greatly to sustainable community development, partly solving the current failure to promote urban sustainability. This supports Ostrom’s notion of the need to gear the institutional design of any community to such exogenous conditions as community attributes, rules and material conditions. However, it would not be appropriate for the Zhongshun experience to be copied directly to other cases [11]. On the other hand, it is true that voluntary groups and active public participation help sustain Zhongshun’s institution in this case, where personnel, resources, and opinions can flow smooth within the community, and promptly and accurately satisfy the needs of the residents. The lack of voluntary groups is still a barrier to the ability of many mainland communities to mobilize public participation organized by the community members themselves. In addition, the community needs at least minimum recognition to enable it to exert some form of self-governance and establish stronger horizontal connections in future. However, this single in-depth case study is not sufficient to conclude a pattern for sustainable urban community development with universal generalizability. More in-depth or comparative case studies and quantitate investigations are encouraged in the future to further expand the theories and practice on sustainable urban development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F. and W.M.; methodology, Y.F.; software, Y.F.; validation, W.M.; formal analysis, Y.F. and W.M.; investigation, Y.F.; resources, W.M.; data curation, Y.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.F. and W.M.; writing—review and editing, Y.F. and W.M.; visualization, Y.F.; supervision, W.M.; project administration, W.M.; funding acquisition, W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the 13th five-year plan of philosophy and social sciences project of Guangdong, grant number GD19YGL19; the 13th five-year plan of philosophy and social sciences project of Shenzhen, grant number SZ2019C009; Shenzhen University Start-up Fund, grant number: 00000325/000002110357; the Major Project of National Social Sciences Foundation of China, grant number: 18ZDA108.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our most sincere gratitude to all interviewees who have given us valuable information during the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, X. Trajectory of urban sustainability concepts: A 35-year bibliometric analysis. Cities 2017, 60, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprotti, F. Eco-urbanism and the Eco-city, or, Denying the Right to the City? Antipode 2014, 46, 1285–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pow, C.P.; Neo, H. Seeing Red Over Green: Contesting Urban Sustainabilities in China. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 2256–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischen, P.A.; Homsy, G.C.; Lipo, C.P.; Holahan, R.; Imbruce, V.; Pape, A.; Zhu, W.; Graney, J.; Zhang, Z.; Holmes, L.M. A Foundation for Measuring Community Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J.; Abram, S. Defining the limits of community governance. J. Rural Stud. 1998, 14, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Institutional Rational Choice: An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2007; pp. 21–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, S.; Gintis, H. Social capital and community governance. Econ. J. 2002, 112, F419–F436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.; Cardoso, P.P.; Arcaute, E.; Christensen, K. Complexity approaches to self-organisation: A case study from an Irish eco-village. Kybernetes 2011, 40, 536–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A behavioral approach to the rational choice theory of collective action: Presidential address, American Political Science Association, 1997. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1998, 92, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.P.; Ostrom, E. An Analytical Agenda for the Study of Decentralized Resource Regimes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Collective action and the evolution of social norms. J. Nat. Resour. Policy Res. 2014, 6, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabareen, Y.R. Sustainable urban forms—Their typologies, models, and concepts. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2006, 26, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatn, A. An institutional analysis of payments for environmental services. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Huang, L. The Reconstruction of Community Public Service Supply Order in China; Univ. Electronic Science & Technology China Press: Chengdu, China, 2014; pp. 492–498. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Xiong, H. Study on Governance of Rural Minority Communities in Western China; Univ. Electronic Science & Technology China Press: Chengdu, China, 2010; pp. 481–486. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, K.; Burdess, N. Governance at community level: Small towns in rural Victoria. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 2005, 40, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ranson, S. Remaking public spaces for civil society. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2012, 53, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Gardner, R.; Walker, J. Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Burger, J.; Field, C.B.; Norgaard, R.B.; Policansky, D. Revisiting the commons: Local lessons, global challenges. Science 1999, 284, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yasnoff, W.A.; Shortliffe, E.H. Lessons Learned from a Health Record Bank Start-up. Methods Inf. Med. 2014, 53, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, K.; Dennis, J.; Kilpatrick, S.; Farmer, J. From passive welfare to community governance: Youth NGOs in Australia and Scotland. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2010, 32, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, K.; Burdess, N. New community governance in small rural towns: The Australian experience. J. Rural Stud. 2004, 20, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.; Currie, M.; Kenny, A.; Munoz, S.A. An exploration of the longer-term impacts of community participation in rural health services design. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 141, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenkorf, N. Sustainable community development through sport and events: A conceptual framework for Sport-for-Development projects. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseland, M. Sustainable community development: Integrating environmental, economic, and social objectives. Prog. Plan. 2000, 54, 73–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryudi, A.; Devkota, R.R.; Schusser, C.; Yufanyi, C.; Salla, M.; Aurenhammer, H.; Rotchanaphatharawit, R.; Krott, M. Back to basics: Considerations in evaluating the outcomes of community forestry. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F. Some Good Experiences to the Administration of the Participatory Community Governance and Its Enlightenment—A Case Study of Qingyuan Sub-District Office of Beijing DaXing District. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Applied Mathematics, Statistics and Public Administration, Beijing, China, 15 October 2014; pp. 846–851. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.F.; Chen, W. Research on the Problems of Resident Participation from the Perspective of Community Governance—Take X Community in Chongqing as an Example; Univ. Electronic Science & Technology China Press: Chengdu, China, 2010; pp. 676–686. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M.; Arnold, G.; Tomas, S.V. A Review of Design Principles for Community-based Natural Resource Management. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D. An Introduction to IAD and the Language of the Ostrom Workshop: A Simple Guide to a Complex Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H.; Lee, T.K. A study on building sustainable communities in high-rise and high-density apartments-Focused on living program. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsner, C. Social exclusion and participation in community development projects: Evidence from Senegal. Soc. Policy Adm. 2004, 38, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuri, J.N.; Moon, J.; Idemudia, U. Corporate Innovation and Sustainable Community Development in Developing Countries. Bus. Soc. 2012, 51, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZCDA. Community Development Report. 2015. Available online: http://www.chungshun.org.tw/20160606154200 (accessed on 17 November 2016).

- DBAS. Database of Department of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Taipei City. 2015. Available online: http://dbas.gov.taipei/np.asp?ctNode=6151&mp=120001 (accessed on 17 November 2016).

- WDO. Statistics from Wenshan District Office. 2015. Available online: http://li.taipei/ws_zhongshun/36166_01 (accessed on 17 November 2016).

- Archer, D. Finance as the key to unlocking community potential: Savings, funds and the ACCA programme. Environ. Urban. 2012, 24, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, B.L. Assessing variation in civil society organizations-China’s homeowner associations in comparative perspective. Comp. Polit. Stud. 2008, 41, 1240–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J. Prospects for village self-governance in China. J. Peasant Stud. 1998, 25, 86–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).