Sustainability Practices of Higher Education Institutions in Hong Kong: A Case Study of a Sustainable Campus Consortium

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction to Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium (HKSCC)

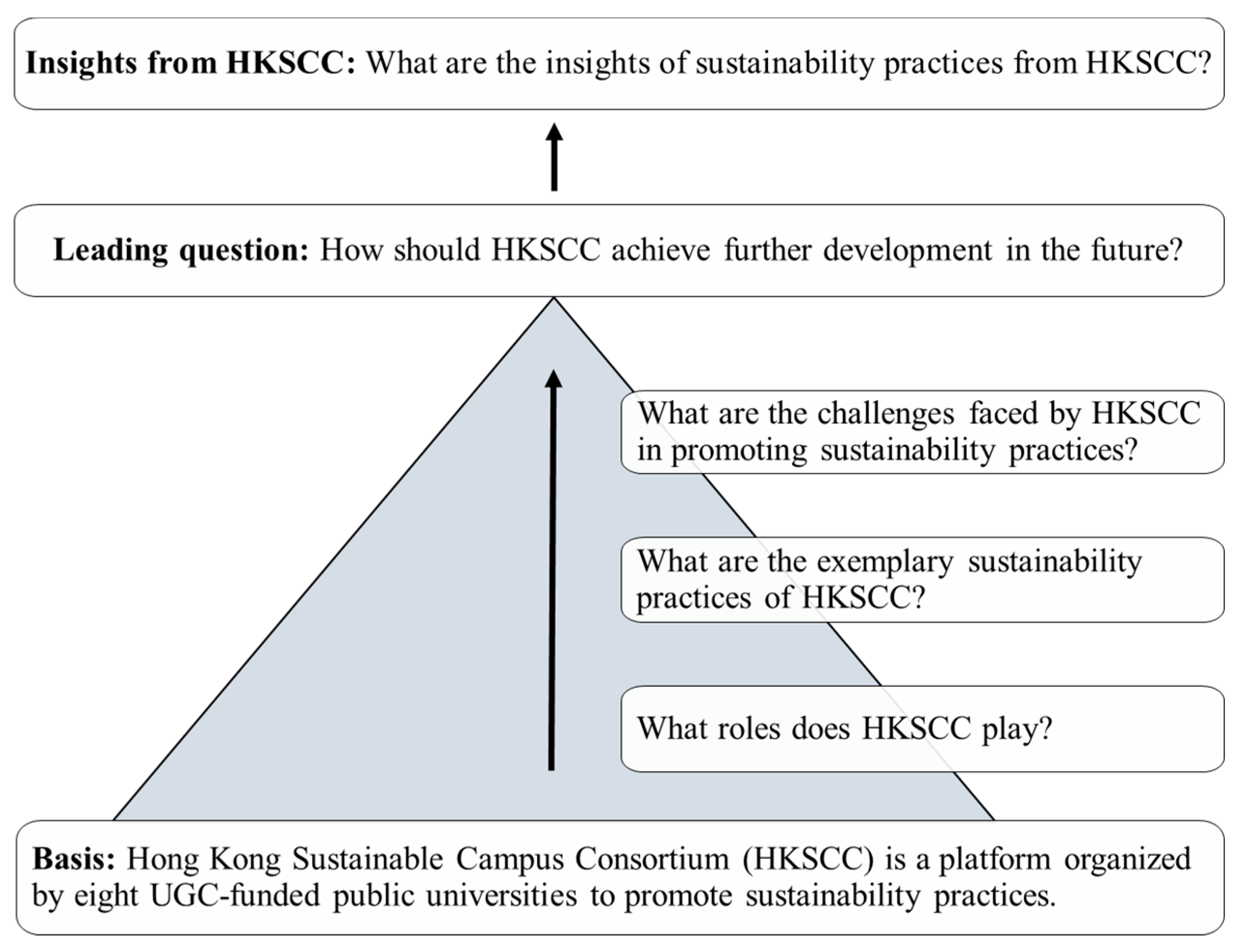

1.2. Research Objective and Research Questions

- What roles does HKSCC play?

- What are the exemplary sustainability practices of HKSCC?

- What are the challenges faced by HKSCC in promoting sustainability practices?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability Accounting in Higher Education Institutions

- Constant learning

- Rapid rebound from negative occurrences

- Limited or “safe failure”

- Flexibility

- Spare capacity.

2.2. Sustainability Practices in Hong Kong Higher Education Institutions

3. Research Design

3.1. Analysis Framework

3.2. Study Participants and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Roles of HKSCC

The Consortium holds no power and is supported by the leadership of the universities. It has the role recognized by the Hong Kong government and the environment bureau about how to help [the] eight universities work effectively. The Consortium aims to serve as a place of pulling together best practices and encouraging universities to behave sustainably. The universities choose their representatives to work for the Consortium, where communication transpires.(SP01)

4.2. Good Practices

4.3. Challenges

5. Discussion

5.1. Future Development of HKSCC

5.2. Implications from HKSCC

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neubauer, D.; Mok, K.H.; Jiang, J. The Sustainability of Higher Education in an Era of Post-Massification; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, D.S.L.; Mok, K.H. The Political Economy of Higher Education Governance in Asia: Challenges, Trends and Trajectories. In Transformations in Higher Education Governance in Asia: Policy, Politics and Progress; Jarvis, D.S.L., Mok, K.H., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brusca, I.; Labrador, M.; Larren, M. The Challenge of Sustainability and Integrated Reporting at Universities: A Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K. Campus Sustainability in Chinese Higher Education Institutions: Focuses, Motivations and Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. The State of Sustainability Reporting in Universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, C.; Scott, G.; Dzulkifli, A.R. Effective Change Management, Governance and Policy for Sustainability Transformation in Higher Education. Sustainability 2013, 4, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HKSCC (Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium). The Hong Kong Declaration. Available online: http://www.hkscc.edu.hk/hong-kong-declaration (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- HKSCC (Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium). HKSCC Strategic Plan: From Sharing to Developing—Vision and Goals for the Next Eight Year Cycle. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1WrrpNI0XdE23K1EwSpQb6v4fQQHfUA-B/view (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- HKSCC (Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium). Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium Annual Report 2017-2018; HKSCC: Hong Kong, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- HKSCC (Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium). Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium Annual Report 2014-2015; HKSCC: Hong Kong, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- HKSCC (Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium). Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium Annual Report 2015-2016; HKSCC: Hong Kong, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- HKSCC (Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium). Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium Annual Report 2016-2017; HKSCC: Hong Kong, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peršić, M.; Janković, S.; Krivačić, D. Sustainability Accounting: Upgrading Corporate Social Responsibility. In The Dynamics of Corporate Social Responsibility: Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Aluchna, M., Idowu, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M.; Bormann, I.; Kummer, B.; Niedlich, S.; Riechkmann, M. Sustainability Governance at Universities: Using a Governance Equalizer as a Research Heuristic. High. Educ. Policy 2018, 31, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Michelsen, G.; Rieckmann, M.; Thomas, I. Routledge Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, W.L. Sustainable Development at Universities: New Horizons; Peter Lang Scientific Publishers: Frankfurt, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, W.L.; Wu, Y.J.; Brandli, L.L.; Avila, L.V.; Miranda-Azeiteiro, U.; Caeiro, S.; Madruga, L.G. Identifying and Overcoming Obstacles to the Implementation of Sustainable Development at Universities. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2017, 14, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findler, F.; Schonherr, N.; Lozano, R.; Stacherl, B. Assessing the Impact of Higher Education Institutions on Sustainable Development: An Analysis of Tools and Indicators. Sustainability 2019, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, G. Policy, Politics and Policy in Higher Education Sustainable Development. In Routledge Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development; Barth, M., Michelsen, G., Thomas, I., Rieckmann, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- CIES (Comparative and International Education Society). 63rd Annual Conference Program. Available online: https://cies2019.org/wp-content/uploads/cies-2019-print-program.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- An, Y.; Davey, H.; Harun, H. Sustainability Reporting at a New Zealand Public University: A Longitudinal Analysis. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, P.; Sciulli, N. Sustainability Reporting by Australian Universities. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2016, 76, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siboni, B.; del Sordo, C.; Pazzi, S. Sustainability Reporting in State Universities: An Investigation of Italian Pioneering Practices. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sule, O.F.; Greig, A. Embedding Education for Sustainable Development within the Curriculum of UK Higher Educational Institutions: Strategic Priorities. In Sustainable Development Research at Universities in the United Kingdom: Approaches, Methods and Projects; Filho, W.L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Trechsel, L.J.; Zimmermann, A.B.; Graf, D.; Herweg, K.; Lundsgaard-Hansen, L.; Rufer, L.; Tribelhorn, T.; Wastl-Walter, D. Mainstreaming Education for Sustainable Development at a Swiss University: Navigating the Traps of Institutionalization. High. Educ. Policy 2018, 31, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, E.; Lambrechts, W. Fostering the Incorporation of Sustainable Development in Higher Education: Lessons Learned from a Change Management Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba-Hidalgo, D.; Benayas del Álamo, J.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J. Towards a Definition of Environmental Sustainability Evaluation in Higher Education. High. Educ. Policy 2018, 31, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. Sustainability to Resilience: Implications for Global Education and Training; Asia Pacific Higher Education Research Partnership: Hong Kong, China, 2016; Available online: https://apherp.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/karl-kim-sustainability-to-resilience.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2019).

- Neubauer, D. Higher Education Sustainability: Proliferating Meanings. In The Sustainability of Higher Education in an Era of Post-Massification; Neubauer, D., Mok, K.H., Jiang, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rockefeller Foundation. Rebound: Building a More Resilient World; Rockefeller Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Kong Environment Bureau. Sustainable Development Promotion Award for Students of Higher Education Institutions. Available online: https://www.enb.gov.hk/en/susdev/public/sdpa.htm (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef, L.; Bossert, M. The University Campus as a Living Lab for Sustainability: A Practitioner’s Guide and Handbook; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, K.H. Governance, Accountability and Autonomy in Higher Education in Hong Kong. In Transformation in Higher Education Governance in Asia; Jarvis, D., Mok, K.H., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, K.H. Massification of Higher Education, Graduate Employment and Social Mobility in the Greater China Region. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2016, 37, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.H.; Jiang, J. Massification of Higher Education and Challenges for Graduate Employment and Social Mobility: East Asian Experiences and Sociological Reflections. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 63, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Hawkins, J. Massification of Higher Education in Asia: Consequences, Policy Responses and Changing Governance; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, J.; Neubauer, D. Internationalization, Globalization and Institutional Roles in the Face of Rising Nationalism. In Contesting Globalization and Internationalization of Higher Education: Discourse and Responses in the Asia Pacific Region; Neubauer, D., Mok, K.H., Edwards, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Demillo, R. Revolution in Higher Education: How a Small Band of Innovators Will Make College Accessible and Affordable; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Time | Project/Event | Covering Sustainable Development Issues |

|---|---|---|

| 19 June 2015 | China Green Campus Forum | HKSCC serving as the supporting organization to raise sustainability awareness of higher education sector and the community |

| 31 October 2015 | HK Tertiary Schools Conference of Parties (COP) 21 Challenge | The first event held by HKSCC for all tertiary institutions in Hong Kong to raise sustainability awareness of the higher education sector |

| 2016 | Inter-Institutional Purchasing Liaison Group (IPLG) | Implementing sustainable purchasing |

| 2016 | Joint Universities Computer Centre (JUCC) | Implementing sustainable IT practices |

| 12–16 March 2018 | Joint Disposables Campaign—UNIfy: Skip the Straw | First joint-university disposables campaign to raise sustainability awareness in the higher education sector |

| 2019 | Joint Disposables Campaign—Bring Your Own Week | Raising sustainability awareness of the higher education sector |

| Throughout | Dialogue with the Environment Bureau of Hong Kong Government | Major way of communicating with the Hong Kong government on the sustainable development efforts of the higher education sector |

| UGC-Funded University | Sustainability Office/Unit | Number of Staff | Staff Roles and Student Engagement | Attended Sustainability Networks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Hong Kong | Sustainability Office 1 | 5 |

|

|

| Hong Kong Polytechnic University | Campus Sustainability Office 2 | 7 |

|

|

| Chinese University of Hong Kong | Campus Planning and Sustainability Office 3 | 13 |

|

|

| City University of Hong Kong | Sustainability Committee, Office of the Provost 4 | 17 |

|

|

| Hong Kong Baptist University | Task Force on Sustainable Campus 5 | 20 |

|

|

| Education University of Hong Kong | Center for Education in Environmental Sustainability 6 | 44 |

|

|

| Hong Kong University of Science and Technology | Sustainability Unit 7 | 3 |

|

|

| Lingnan University | Office of the Comptroller 8; Science Unit 9 | 4 |

|

|

| Interviewee | Role in HKSCC |

|---|---|

| SP01 | Former Convenor |

| SP02 | University representative |

| SP03 | Member of the Joint University Campaign Sub-Committee |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiong, W.; Mok, K.H. Sustainability Practices of Higher Education Institutions in Hong Kong: A Case Study of a Sustainable Campus Consortium. Sustainability 2020, 12, 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020452

Xiong W, Mok KH. Sustainability Practices of Higher Education Institutions in Hong Kong: A Case Study of a Sustainable Campus Consortium. Sustainability. 2020; 12(2):452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020452

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiong, Weiyan, and Ka Ho Mok. 2020. "Sustainability Practices of Higher Education Institutions in Hong Kong: A Case Study of a Sustainable Campus Consortium" Sustainability 12, no. 2: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020452

APA StyleXiong, W., & Mok, K. H. (2020). Sustainability Practices of Higher Education Institutions in Hong Kong: A Case Study of a Sustainable Campus Consortium. Sustainability, 12(2), 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020452