The Mediating Role of Person-Job Fit between Person-Organisation Fit and Intention to Leave the Job: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Person-Organisation Fit and Person-Job Fit

2.2. Turnover Intention

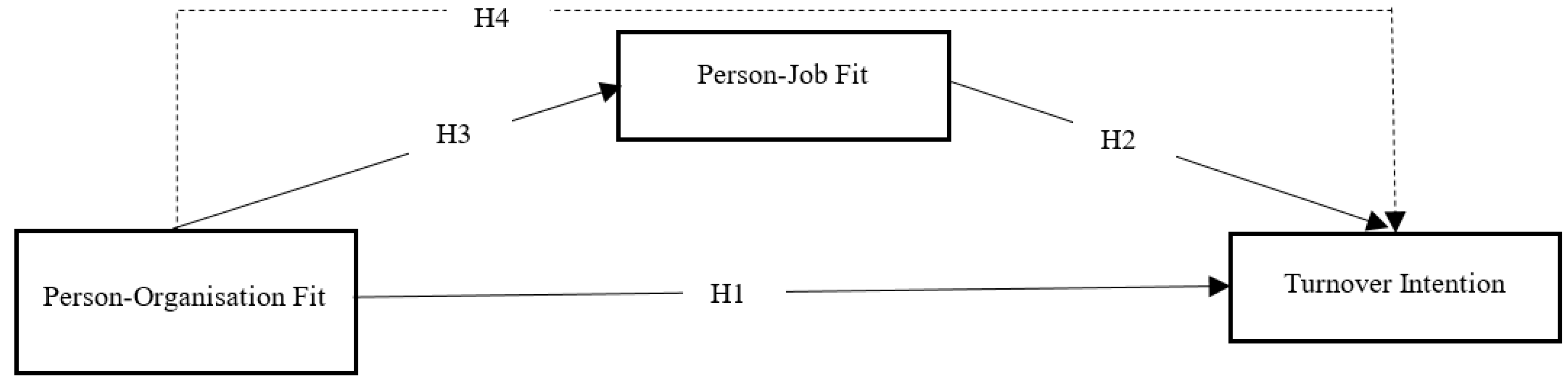

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Person-Job and Turnover Intention

3.2. Person-Organisation Fit and Person-Job Fit

3.3. Person-Job Fit as a Mediator

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

4.2. Research Instruments

4.3. Data Analysis Tools

4.4. Results

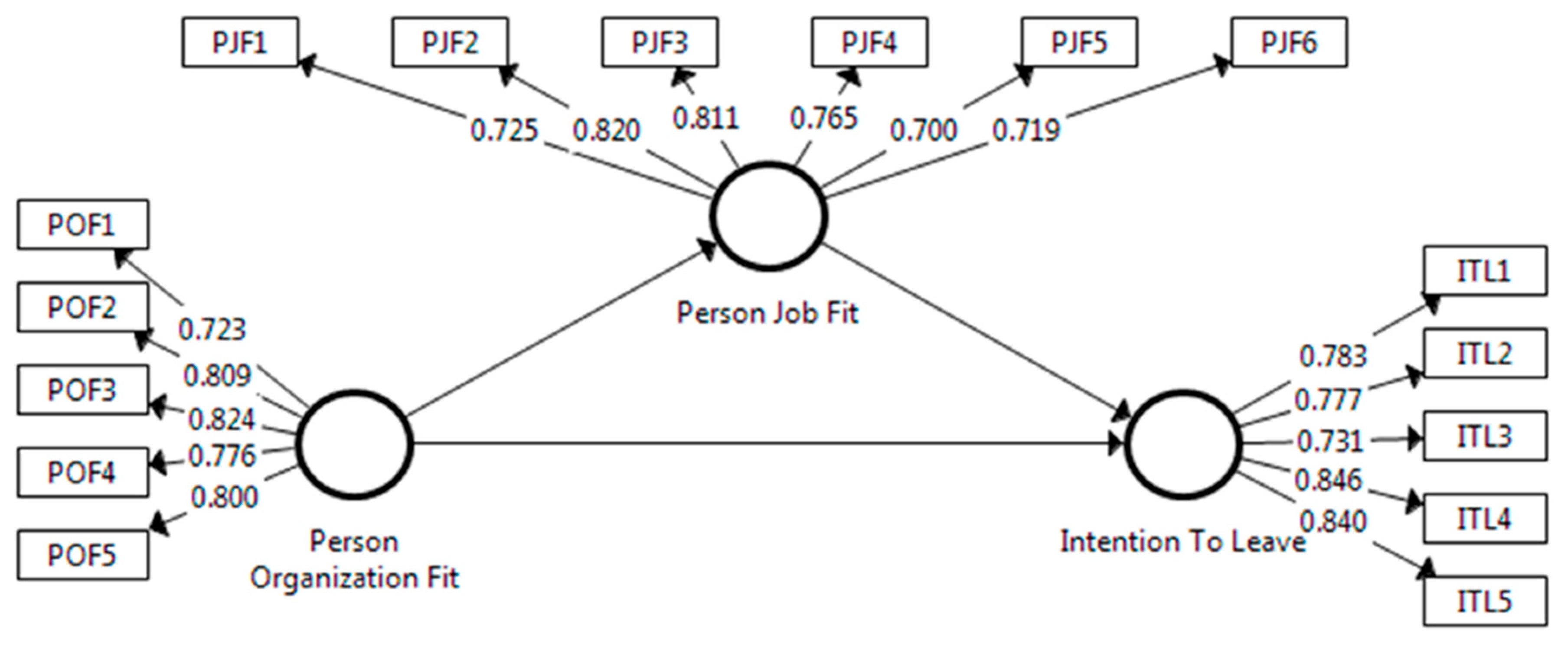

Constructs Reliability and Validity

4.5. Structural Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Implications

7. Research Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schloss, E.P.; Flanagan, D.M.; Culler, C.L.; Wright, A.L. Some hidden costs of faculty turnover in clinical departments in one academic medical center. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber, K.L. Does the environment matter? Faculty satisfaction at 4-year colleges and universities in the USA. High. Educ. 2018, 78, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrar-Ul-Haq, M.; Ali, H.Y.; Anwar, S.; Iqbal, A.; Iqbal, M.B.; Suleman, N.; Sadiq, I.; Haris-ul-Mahasbi, M. Impact of organisational politics on employee work outcomes in higher education institutions of Pakistan: Moderating role of social capital. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 8, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, S.; Jangraiz, K. An Analysis of the Factors Affecting Turnover Intensions: Evidence from Private Sector Universities of Peshawar. J. Soc. Adm. Sci. 2015, 2, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsrud, L.K.; Rosser, V.J. Faculty Members’ Morale and Their Intention to Leave: A Multilevel Explanation. J. High. Educ. 2002, 73, 518–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-Organization Fit: An Integrative Review of Its Conceptualisations, Measurement, and Implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, R.M.; Feldman, D.C. Integrating the levels of person-environment fit: The roles of vocational fit and group fit. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andela, M.; van der Doef, M. A Comprehensive Assessment of the Person–Environment Fit Dimensions and Their Relationships with Work-Related Outcomes. J. Career Dev. 2019, 46, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.H.; McDonald, B.; Park, J. Person–Organization Fit and Turnover Intention: Exploring the Mediating Role of Employee Followership and Job Satisfaction through Conservation of Resources Theory. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2018, 38, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrow, J.B.; Behrend, T.S. Person-environment fit is a formative construct. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 103, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-brown, A.M.Y.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of Individuals’ Fit at Work: A Meta-Analysis of Person—Job, Person—Organization, Person—Group, and Person—Supervisor Fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, B. Work role stressors and employee outcomes: Investigating the moderating role of subjective person-organisation and person-job fit perceptions in Indian organisations. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2016, 24, 390–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanti, S.; Udin, U.; Widodo, W. Person-Organization Fit, Person-Job Fit, and Innovative Work Behavior: The Role of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Adm. 2018, 6, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D.; Resenterra, F.; Siggen, M. Antecedents of Job Satisfaction, Organisational Commitment and Stress in a Public Hospital: A P-E Fit Perspective. Public Organ. Rev. 2014, 14, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Sparrow, P.; Cooper, C. The relationship between person-organisation fit and job satisfaction. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A.R.; Gallagher, V.C.; Brouer, R.L.; Sablynski, C.J. When person-organization (mis) fit and (dis) satisfaction lead to turnover: The moderating role of perceived job mobility. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, L.M.; Yu, T.W. How can managers promote salespeople’s person-job fit?: The effects of cooperative learning and perceived organisational support. Learn. Organ. 2016, 23, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.Y.T. Inter-Relationships among Different Types of Person-Environment Fit and Job Satisfaction. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 65, 38–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, J.W.; Cyr, L.A. An integrative analysis of person-organisation fit theories. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2004, 12, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.C.; Lee, Y.L.; Tseng, M.M. Person-organisation fit and turnover intention: Exploring the mediating effect of work engagement and the moderating effect of demand-ability fit. J. Nurs. Res. 2014, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, A.S.; Saufi, R.A.; Singh, H. Understanding linkage between human resource management practices and intention to leave: A moderated-mediation conceptual model. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Information Management & Management Science, Chengdu, China, 24–26 August 2018; pp. 114–118. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Meng, Y. High-performance work systems and employee engagement: Empirical evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 56, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astakhova, M.N. Explaining the effects of perceived person-supervisor fit and person-organisation fit on organisational commitment in the U.S. and Japan. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasentin, K.A.; Chapman, D.S. Subjective person-organisation fit: Bridging the gap between conceptualisation and measurement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Matching People and Organisations—Selection and Socialisation in Public Accounting Firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauver, K.J.; Kristof-Brown, A. Distinguishing between Employees’ Perceptions of Person–Job and Person–Organization Fit. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 59, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; Den Hartog, D.N.; Boselie, P.; Paauwe, J. The relationship between perceptions of HR practices and employee outcomes: Examining the role of person–organisation and person–job fit. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 138–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, A.S.; Saufi, R.A.; Mansor, N.N.A. Person-organisation fit and job opportunities matter in HRM practices-turnover intention relationship: A moderated mediation model. Amazon. Investig. 2019, 8, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W.; Gaertner, S. A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents and Correlates of Employee Turnover: Update, Moderator Tests, and Research Implications for the Next Millennium. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, A.L.; Eberly, M.B.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. Surveying the forest: A meta-analysis, moderator investigation, and future-oriented discussion of the antecedents of voluntary employee turnover. Pers. Psychol. 2018, 71, 23–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluedorn, A.C. A Unified Model of Turnover from Organisations. Hum. Relat. 1982, 35, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W.H. Intermediate Linkage in the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 1977, 62, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T. Strategies for adapting to high rates of employee turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1984, 23, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, D.R.; Johnson, J.L.; Daily, C.M. On the use of “intent to...” variables in organisational research: An empirical and cautionary assessment. Hum. Relat. 1999, 52, 1337–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Price, J.L.; Mueller, C.W. Causal Model of Turnover for Nurses. Acad. Manag. 1981, 24, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, J.K.; Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W. A Comparison of Structural Models Representing Turnover Cognitions. J. Vocat. Behav. 1998, 53, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B. The People Make the Place 58. Pers. Psychol. 1987, 40, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K.J.; Kristof-Brown, A. Toward a multidimensional theory of person-environment fit. J. Manag. Issues 2006, 18, 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Rurkkhum, S. The impact of person-organisation fit and leader-member exchange on withdrawal behaviors in Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2018, 10, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribando, S.J.; Evans, L. Change happens: Assessing the initial impact of a university consolidation on faculty. Public Pers. Manag. 2015, 44, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C.; Skidmore, S.T.; Combs, J.P. The hiring process matters: The role of person–job and person–organisation fit in teacher satisfaction. Educ. Adm. Q. 2017, 53, 448–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; Biron, M. Temporal issues in person–organisation fit, person–job fit and turnover: The role of leader–member exchange. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 2177–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L. Sampling in developmental science: Situations, shortcomings, solutions, and standards. Dev. Rev. 2013, 33, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.C.; Idris, M.A.; Tuckey, M. Supervisory coaching and performance feedback as mediators of the relationships between leadership styles, work engagement, and turnover intention. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2019, 22, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J.; Caldwell, D.F. People and organisational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-fit. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 487–516. [Google Scholar]

- Cennamo, L.; Gardner, D. Generational differences in work values, outcomes and person-organisation values fit. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.F.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Ringle, C.M.; Schlägel, C. A critical look at the use of SEM in international business research. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 376–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vekeman, E.; Devos, G.; Valcke, M.; Rosseel, Y. Do teachers leave the profession or move to another school when they don’t fit? Educ. Rev. 2017, 69, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, A.S.; Saufi, R.A.; Mansor, N.N.A.; Singh, H. Work-life balance practices and turnover intention: The mediating role of person-organisation fit. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2019, 6, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) | POF | PJF | ITL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-organisation fit (POF) | 3.27 | 0.78 | 1 | ||

| Person-job fit (PJF) | 3.00 | 0.83 | 0.56 ** | 1 | |

| Intention to leave (ITL) | 3.35 | 1.01 | −0.27 ** | −0.40 ** | 1 |

| Constructs | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | (AVE) | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover Intention | 0.857 | 0.896 | 0.635 | |

| Person-job fit | 0.852 | 0.890 | 0.575 | 1.42 |

| Person-organisation fit | 0.846 | 0.890 | 0.619 | 1.45 |

| Constructs | ITL | PJF | POF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to leave (ITL) | 0.797 | ||

| Person-job fit | −0.421 | 0.758 | |

| Person-organisation fit | −0.283 | 0.546 | 0.787 |

| Constructs | ITL | PJF | POF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to leave | - | ||

| Person-job fit | 0.465 | - | |

| Person-organisation fit | 0.330 | 0.636 | - |

| Hypothesised Path | β-Value | t-Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POF → Intention to leave | −0.076 | 1.023 | 0.153 | Not Supported |

| POF → PJF | 0.546 | 10.437 | 0.000 | Supported |

| PJF → Intention to leave | −0.379 | 5.748 | 0.000 | Supported |

| POF → PJF → Intention to leave | −0.207 | 4.781 | 0.000 | Supported |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saufi, R.A.; Mansor, N.N.A.; Kakar, A.S.; Singh, H. The Mediating Role of Person-Job Fit between Person-Organisation Fit and Intention to Leave the Job: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198189

Saufi RA, Mansor NNA, Kakar AS, Singh H. The Mediating Role of Person-Job Fit between Person-Organisation Fit and Intention to Leave the Job: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):8189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198189

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaufi, Roselina Ahmad, Nur Naha Abu Mansor, Abdul Samad Kakar, and Harcharanjit Singh. 2020. "The Mediating Role of Person-Job Fit between Person-Organisation Fit and Intention to Leave the Job: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 8189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198189

APA StyleSaufi, R. A., Mansor, N. N. A., Kakar, A. S., & Singh, H. (2020). The Mediating Role of Person-Job Fit between Person-Organisation Fit and Intention to Leave the Job: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability, 12(19), 8189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198189