Euroregions and Local and Regional Development—Local Perceptions of Cross-Border Cooperation and Euroregions Based on the Euroregion Beskydy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Role of Cross-Border Cooperation and the Euroregions in the Process of Local and Regional Development

2.1. Local and Regional Development—Models and Factors

2.2. The Objectives of the Euroregions and Cross-Border Cooperation

- Awareness raising cooperation, i.e., cross-border “relations of good neighborliness”. It is the type of cross-border cooperation that requires the least political commitment. In practice, this very often means regular bilateral visits or town twinning arrangements to promote cultural and commercial ties.

- Mutual aid cooperation, which may take place on an ad hoc basis, required only in the event of an emergency, but may also constitute a formal standing arrangement for risk cooperation or crisis management on a continuous basis between adjacent public authorities.

- Functional cooperation, that is, longer lasting, requiring more resources, and greater involvement of neighboring local/regional political and administrative authorities. These cooperation projects aim to solve problems, create business opportunities, promote cultural exchange, and reduce invisible barriers to worker mobility.

- Common management of public resources/services. This type of CBC goes beyond the implementation of EU regional funds and seeks common strategies for the reorganization and rationalization of state services, benefits, and other public funded provisions in function of border regions [90].

3. Objectives and Methodology

- the exchange of experience and information on the development of the region and the labor market,

- spatial planning and construction,

- solving common problems in the field of transport, communication, communications, and telecommunications,

- solving common problems regarding ecology and the natural environment,

- solving common problems concerning economy, trade, industry, and small and medium enterprises,

- solving common problems related to agriculture, forestry, and the food industry,

- tourism development, tourism taking into account its improvement in the border area,

- undertaking cooperation in the field of education, youth exchange and sport, and education,

- supporting activities for cultural exchange and protection of the common cultural heritage,

- supporting activities related to the prevention and removal of the effects of natural disasters, as well as care for the security of citizens and mutual cooperation of rescue services within the Euroregion.

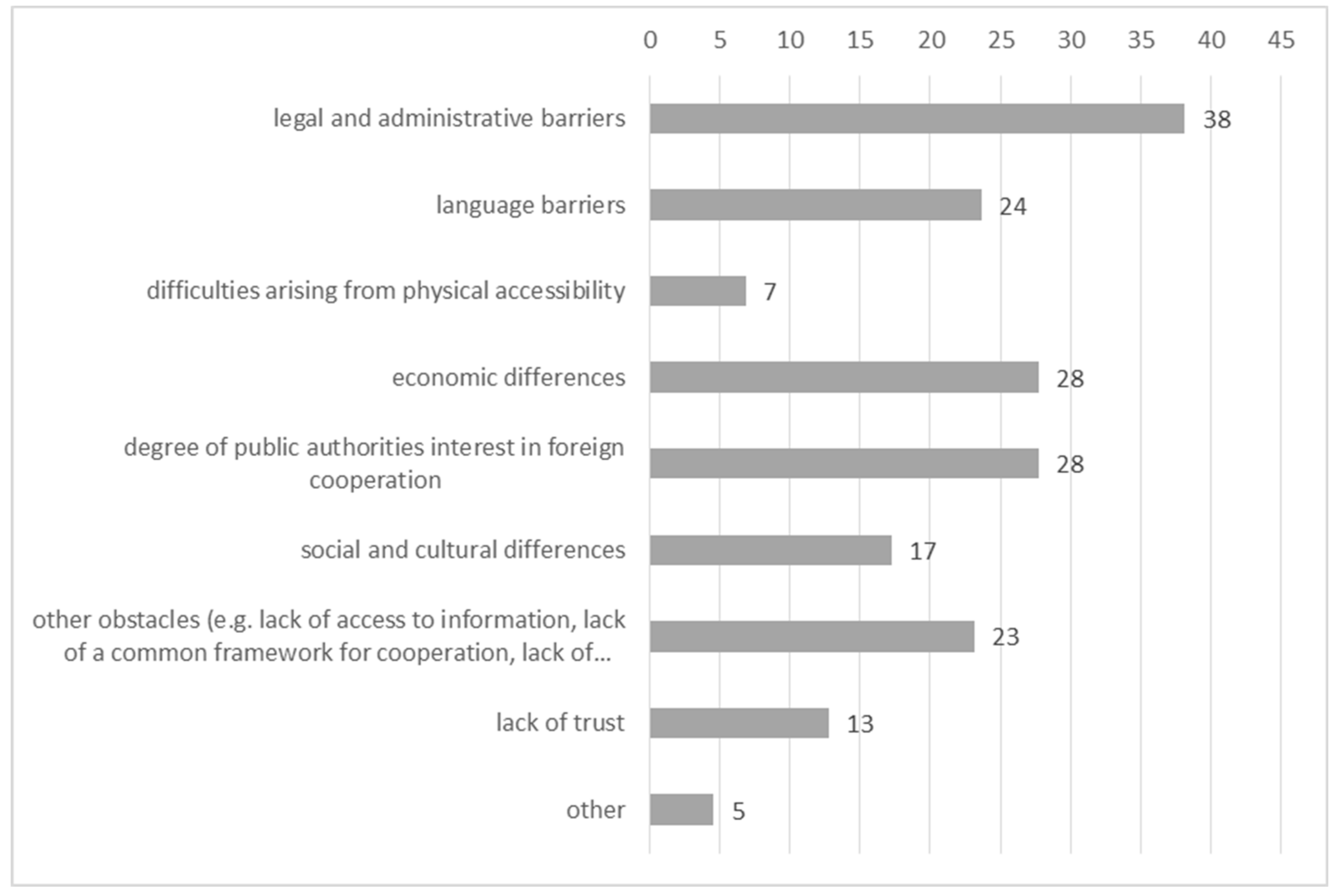

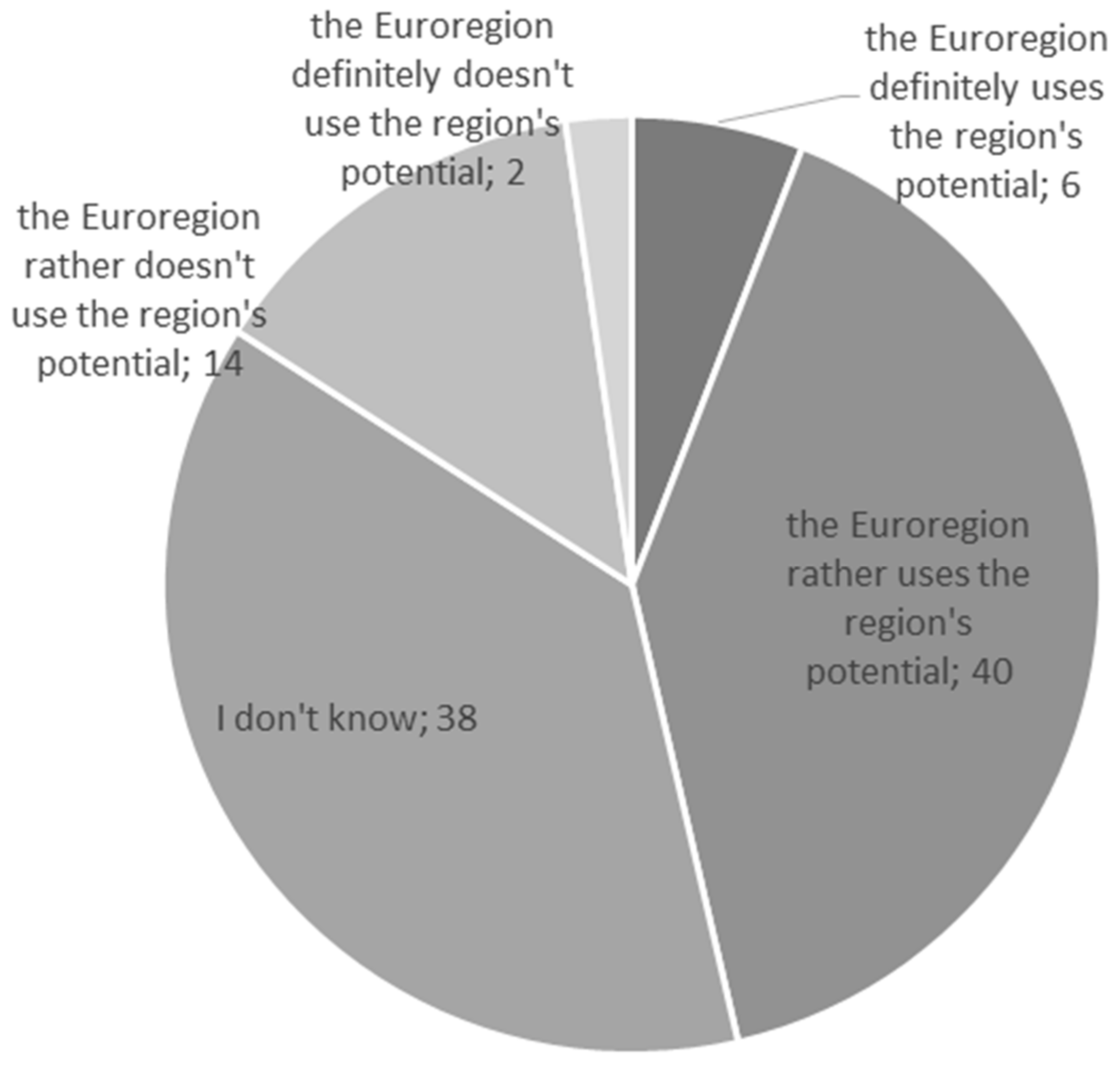

4. Results

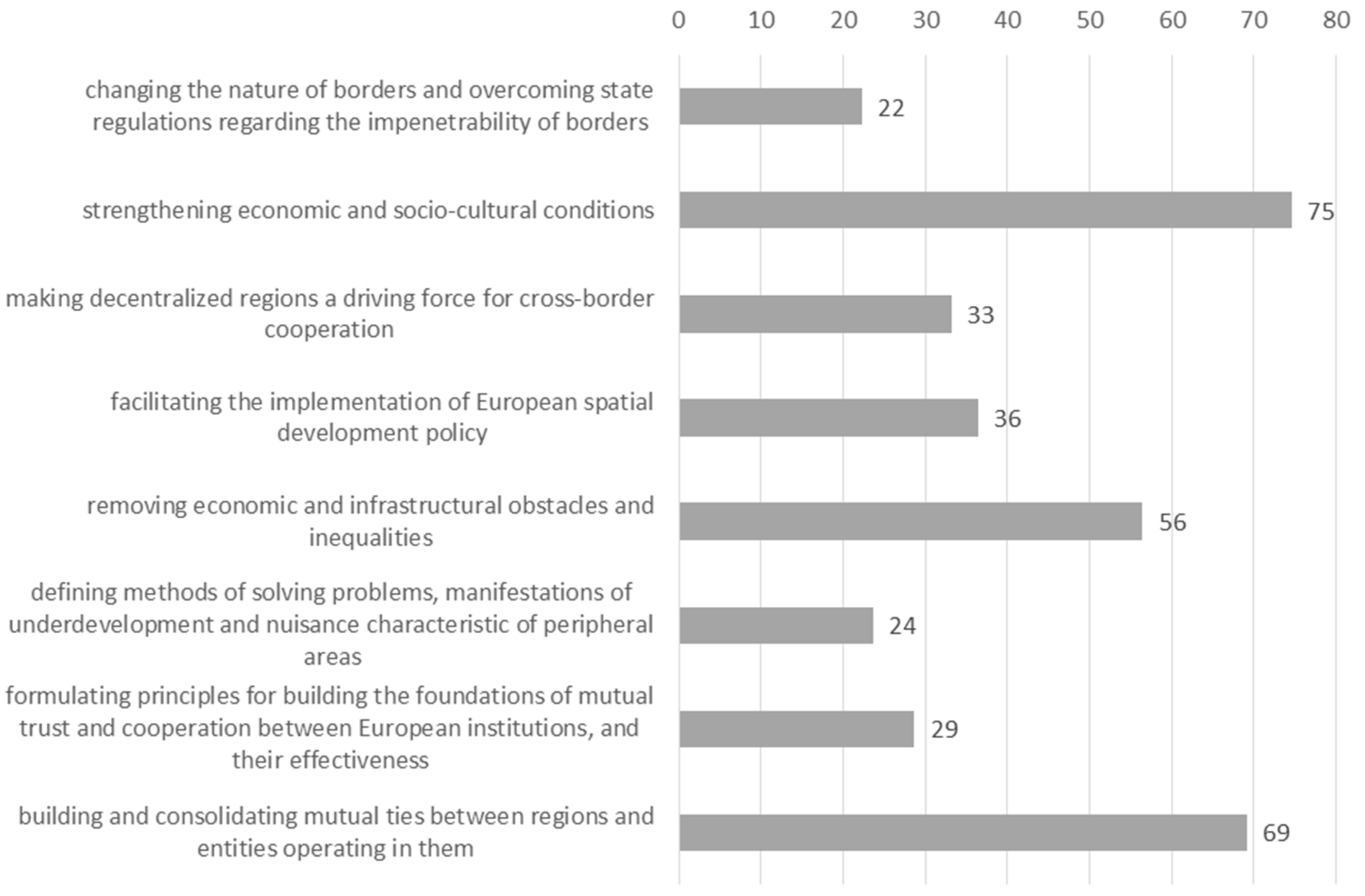

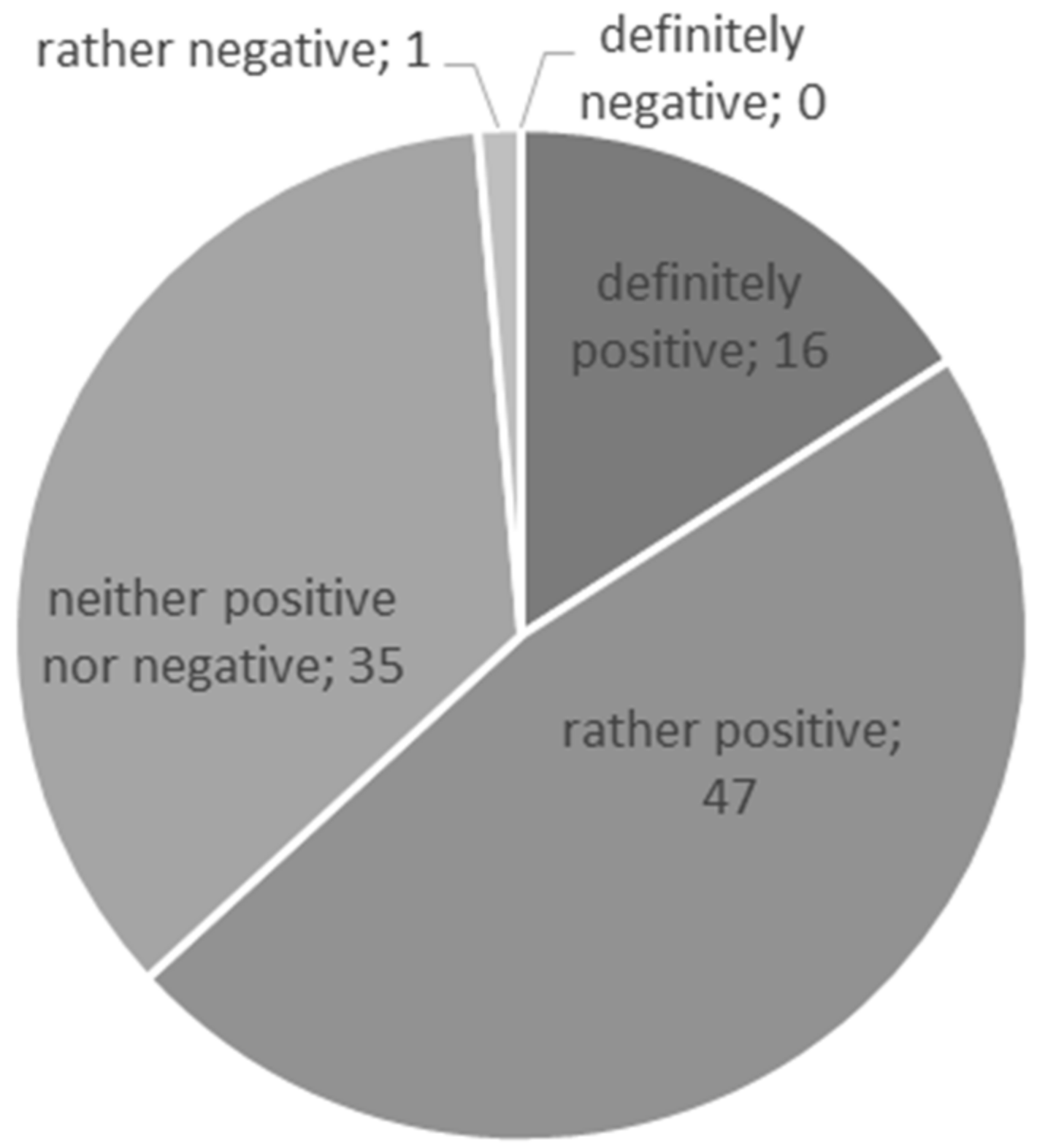

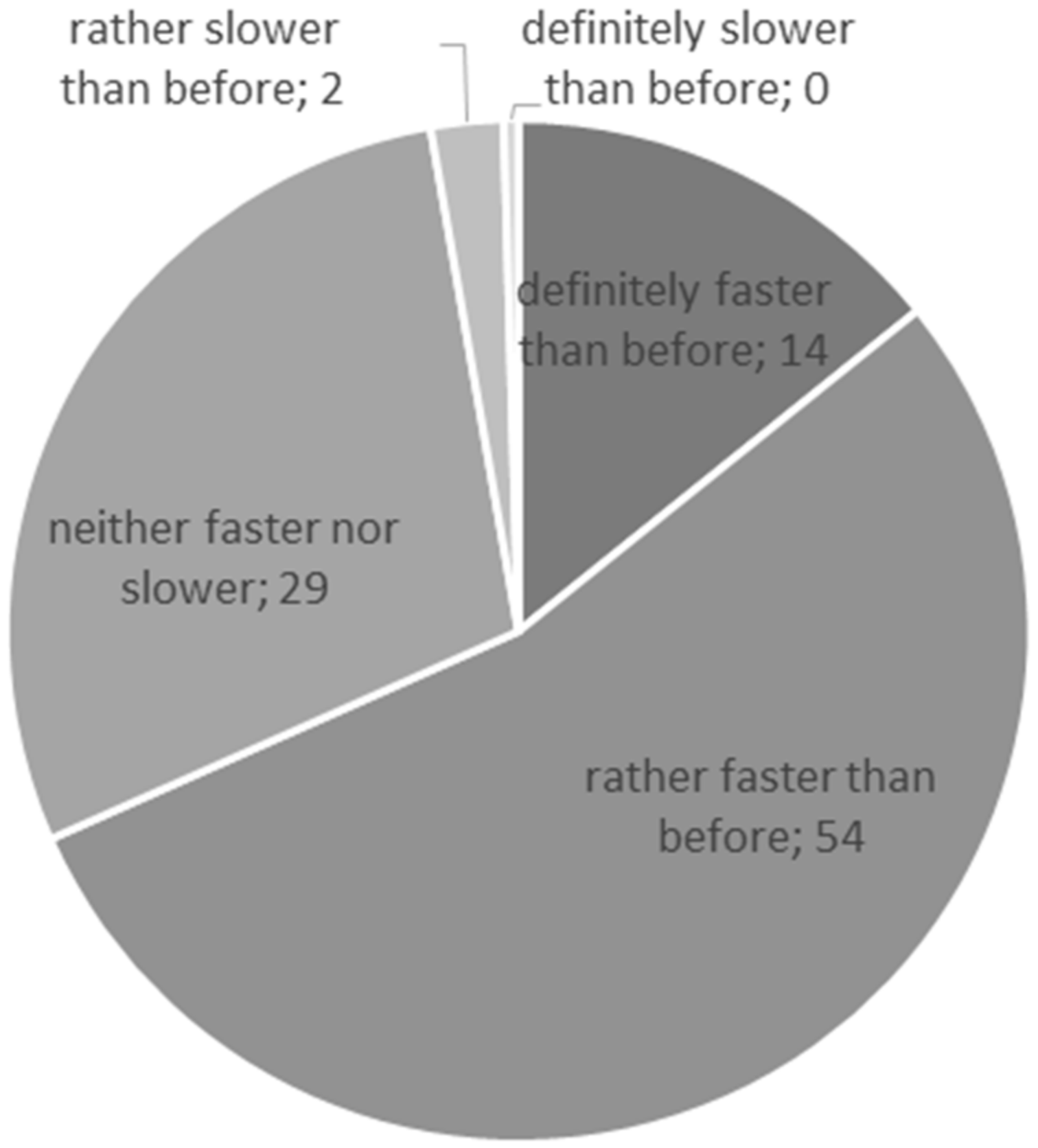

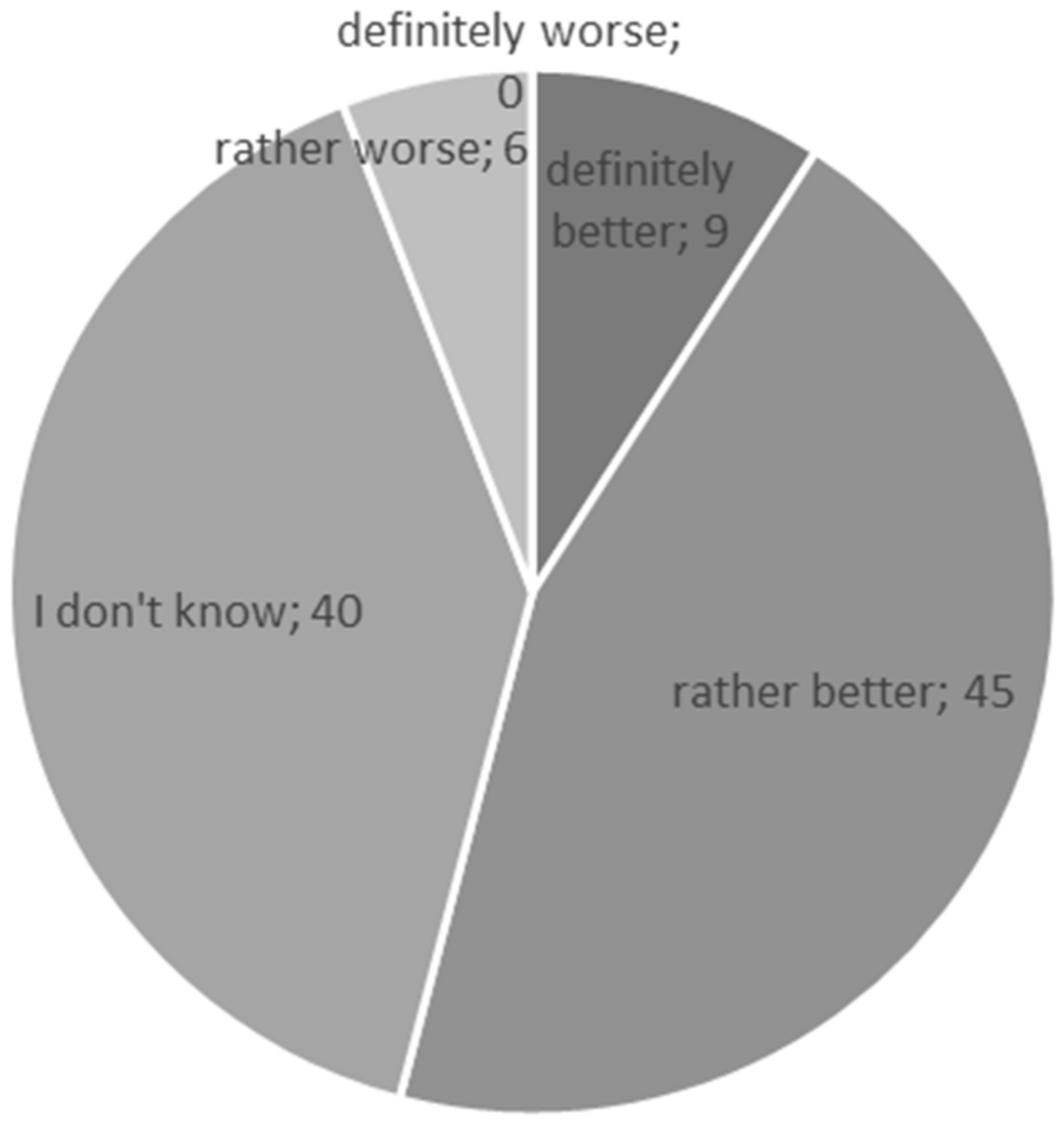

4.1. The Way of Perception of Euroregions

4.2. Evaluation of the Euroregion Beskydy

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, R. Cross-Border Resource Management. Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- Cappellano, F.; Rizzo, A. Economic drivers in cross-border regional innovation systems. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2019, 6, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtum, H.; Strüver, A. Border, strangers, doors and bridges. Space Polity 2002, 6, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.J. Borders, bridges and branding: The transformation of the Öresund region into an imagined space. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2006, 14, 1015–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gómez, T.; Gualda, E. Reporting a bottom-up political process: Local perceptions of cross-border cooperation in the southern Portugal-Spain region. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2014, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, C.J. Regional Development Theory: Conceptual Foundations, Classic Works, and Recent Developments. J. Plan. Lit. 2003, 18, 131–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Tomaney, J. Local and regional development in the Global North and South. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2014, 14, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.M. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlauf, S.N.; Kourtellos, A.; Minkin, A. The local Solow growth model. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, J. Convergence or divergence? The impact of technology on “Why Growth Rates Differ”. J. Evol. Econ. 1995, 5, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, T.W. Economic growth and capital accumulation. Econ. Rec. 1956, 32, 334–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankiw, N.G.; Romer, D.; Weil, D.N. A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 1992, 107, 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.J. Central Place Theory. Web Book of Regional Science; Grant, I.T., Ed.; Regional Research Institute, West Virginia University: Morgantown, WV, USA, 1985; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tiebout, C.M. Exports and regional economic growth. J. Political Econ. 1956, 64, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiebout, C.M. Exports and regional economic growth: Rejoinder. J. Political Econ. 1956, 64, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Exports and regional economic growth: A reply. J. Political Econ. 1956, 64, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Location theory and regional economic growth. J. Political Econ. 1955, 63, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perloff, H.S.; Edgar, S.D., Jr.; Eric, E.L.; Richard, F.M. Regions, Resources and Economic Growth; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Borts, G.; Stein, J. Economic Growth in a Free Market; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, J.G. Regional inequality and the process of national development: Adescription of the patterns. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1965, 13, 158–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J.; Sala-i-Martin, X. Economic Growth; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Perroux, F. Economic space: Theory and applications. Q. J. Econ. 1950, 64, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, A.O. The Strategy for Economic Development; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Meardon, S.J. Modeling agglomeration and dispersion in city and country: Gunnar Myrdal, Francois Perroux, and the New Economic Geography. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2001, 60, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, E.M.; Fisher, J.L. Research in regional economic growth. In Problems in the Study of Economic Growth; Universities-National Bureau Committee on Economic Research, Ed.; National Bureau of Economic Research: New York, NY, USA, 1949; pp. 173–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, M. The stages of economic development from an opportunity perspective: Rostow extended. Geopolitics Hist. Int. Relat. 2012, 2, 52–80. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, W.R. A Preface to Urban Economics; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.V. The sizes and types of cities. Am. Econ. Rev. 1974, 64, 640–656. [Google Scholar]

- Rostow, W.W. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (1960). In The Globalization and Development Reader: Perspectives on Development and Global Change, 2nd ed.; Roberts, J.T., Hite, A.B., Chorev, N., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- McMichael, P. Development and Social Change: A Global Perspective, 6th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; p. 424. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Cass, D. Optimum growth in an aggregative model of capital accumulation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1965, 32, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, T.C. On the Concept of Optimal Economic Growth; Cowles Foundation Discussion Papers 163; Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics, Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, H.W. Regional Growth Theory; Macmillan: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Nijkamp, P.; Poot, J. Spatial perspectives on new theories of economic growth. Ann. Reg. Sci. 1998, 32, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Prebisch, R. The Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems; Department of Economic Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 1950; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, G.A. Dependent Accumulation and Underdevelopment; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1978; p. 226. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Global Capitalism Towards the Theory of Uneven Geographical Development; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blakely, E.; Bradshaw, T. Planning Local Economic Development: Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, J.; Green Leigh, N. Economic Revitalization: Cases and Strategies for City and Suburb, 5th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stimson, R.; Stough, R.R. Regional economic development methods and analysis: Linking theory to practice. In Theories of Local Economic Development: Linking Theory to Practice; Rowe, J.E., Ed.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2008; pp. 169–192. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, A.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Tomaney, J. What kind of local and regional development and for whom? Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A. Global networks and local developments: Agendas for development geography. J. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2003, 94, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cypher, J.M.; Dietz, J.L. The Process of Economic Development, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Reconciling top-down and bottom-up development policies. Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Tomaney, J. Local and Regional Development, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; p. 328. [Google Scholar]

- Markowski, T. Zarządzanie Rozwojem Miast; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Howaniec, H. Znaczenie kształtowania wizerunku miejsca docelowego w rozwoju lokalnym na przykładzie “Beskidzkiej 5”. In Teoria i Praktyka Rozwoju Lokalnego i Regionalnego; Barcik, R., Biesok, G., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe ATH: Bielsko-Biała, Poland, 2009; pp. 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Perkmann, M. Euroregions: Institutional Entrepreneurship in the European Union. In Globalization, Regionalization and Cross-Border Regions; Perkmann, M., Sum, N.-L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2002; pp. 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Malinovský, J.; Sucháček, J. Velký Anglicko-Český Slovník Regionálního Rozvoje a Regionální Politiky EU; VŠB-Technical University: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2006; p. 956. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, O.T.; Hooper, B. Cross-Border Governance in the European Union, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Durà, A.; Camonita, F.; Berzi, M.; Noferini, A. Euroregions, Excellence and Innovation across EU borders. A Catalogue of Good Practices; Department of Geography, UAB: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; p. 254. [Google Scholar]

- Howaniec, H.; Kurowska-Pysz, J. Klaster Jako Instrument Rozwoju Polsko-Słowackiej Współpracy Transgranicznej; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Biznesu w Dąbrowie Górniczej: Dąbrowa Górnicza, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J. Opportunities for cross-border entrepreneurship development in a cluster model exemplified by the Polish–Czech border region. Sustainability 2016, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, A.; Miszczuk, A.; Kawałko, B.; Komornicki, T.; Szul, R. The EU’s New Borderland: Cross-Border Relations and Regional Development; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stryjakiewicz, T. The changing role of border zones in the transforming economies of East-Central Europe: The case of Poland. GeoJournal 1998, 44, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guz-Vetter, M. Polsko-niemieckie pogranicze. Szanse i Zagrożenia w Perspektywie Przystąpienia Polski do Unii Europejskiej; Instytut Spraw Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ciok, S. Pogranicze Polsko-Niemieckie. Problemy Współpracy Transgranicznej; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ciok, S.; Raczyk, A. Implementation of the EU Community Initiative INTERREG III A at the Polish-German border an attempt at evaluation. In Cross-Border Governance and Sustainable Spatial Development; Central and Eastern European Development Studies; Leibenath, M., Korcelli-Olejniczak, E., Knippschild, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dołzbłasz, S. Transborder relations between territorial units in the Polish-German borderland. Geogr. Pol. 2012, 85, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczyk, A.; Dołzbłasz, S.; Leśniak-Johann, M. Relacje Współpracy i Konkurencji na Pograniczu Polsko-Niemieckim; Wydawnictwo Gaskor: Wrocław, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Szmigiel-Rawska, K.; Dołzbłasz, S. Trwałość Współpracy Przygranicznej; CeDeWu: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dołzbłasz, S.; Raczyk, A. Transborder co-operation and competition among firms in the Polish-German borderland. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2016, 108, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewski, Ł.D. Polsko-niemiecko-szwedzka współpraca regionalna w latach 2007–2013 w Euroregionie Pomerania. Przegląd Zach. 2010, 3, 192–200. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewski, Ł.D. Transgraniczne powiązania przedsiębiorstw z Frankfurtu nad Odrą i Słubic, Görlitz i Zgorzelca oraz Guben i Gubina. In Współczesne Wyzwania Polityki Regionalnej i Gospodarki Przestrzennej; Ciok, S., Dołzbłasz, S., Eds.; Instytut Geografii i Rozwoju Regionalnego Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewski, Ł.D. Koncepcja Pięciostopniowej Integracji Regionów Przygranicznych; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Krätke, S. Regional Integration or Fragmentation? The German–Polish Border Region in a New Europe. Reg. Stud. 1999, 33, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J.; Knowles, V. The Euroregion and the maximization of social capital: Pro Europa Viadrina. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2002, 12, 154–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brym, M. The enduring importance of national identity in cooperative European Union Borderlands: Polish university students’ perceptions on cross-border cooperation in the Pomerania euro-region. Natl. Identities 2011, 13, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirwaldt, K. The Small Projects Fund and Social Capital Formation in the Polish–German Border Region: An Initial Appraisal. Reg. Stud. 2012, 46, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishar, A.; Dvořák, P.; Hubačíková, V.; Zapletalová, J. Contemporary development of peripheral parts of the Czech-Polish borderland: Case study of the Javorník area. Geogr. Pol. 2013, 86, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorupska, A. Współpraca samorządowa na pograniczu polsko-czeskich. PISM Policy Pap. 2014, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dołzbłasz, S. Sieć współpracy transgranicznej na pograniczu polsko-czeskim. Studia Reg. Lokalne 2016, 4, 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, H.; Opioła, W. Czech–Polish Cross-Border (Non) Cooperation in the Field of the Labor Market: Why Does It Seem to Be Un-De-Bordered? Sustainability 2019, 11, 2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszyk-Białobrzeska, R.; Kisiel, R. Współpraca Transgraniczna Wschodnich Regionów POLSKI; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warmińsko-Mazurskiego: Olsztyn, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miszczuk, A. Zewnętrzna Granica Unii Europejskiej–Ukraina. Możliwości Wykorzystania Dla Dynamizacji Procesów Rozwojowych; Ministerstwo Rozwoju Regionalnego: Warszawa, Poland, 2007.

- Shcherba, H.I. Współczesne problemy transgranicznej współpracy Ukrainy i Polski w świetle badań socjologicznych. In Spójność Społeczno-Ekonomiczna a Modernizacja Regionów Transgranicznych; Woźniak, M.G., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Rzeszowskiego: Rzeszów, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kawałko, B. Granica Wschodnia Jako Czynnik Ożywienia i Rozwoju Społeczno-Ekonomicznego Regionów Przygranicznych; Ministerstwo Rozwoju Regionalnego: Warszawa, Poland, 2008.

- Zieliński, M.J. Cross-Border Co-Operation Between the Kaliningrad Oblast and Poland in the Context of Polish-Russian Relations in 2004–2011. Lith. Foreign Policy Rev. 2012, 28, 11–42. [Google Scholar]

- Poleszczuk, J.; Sztop-Rutkowska, K.; Porankiewicz-Żukowska, A.; Kiszkiel, Ł.; Klimczuk, A.; Mejsak, R.J. Samorządowa i Obywatelska Współpraca Transgraniczna w Województwie Podlaskim; Fundacja Laboratorium Badań i Działań Społecznych SocLab: Białystok, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J.; Greblikaitė, J. The Polish-Slovak cross-border cooperation in the sphere of culture: The case study analysis. Cult. Manag. Sci. Educ. 2017, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, M. The invention of regions: Political restructuring and territorial government in Western Europe. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 1997, 15, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.R.; Cochrane, A. Beyond the territorial fix: Regional assemblages, politics and power. Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 1161–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.W. Bordering, Border Politics and Cross-Border Cooperation in Europe. In Neighbourhood Policy and the Construction of the European External Borders; Celata, F., Coletti, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.W. European politics of borders, border symbolism and cross-border cooperation. In A Companion to Border Studies; Wilson, T.M., Donnan, H., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bufon, M. Spatial and Social (Re)Integration of Border and Multicultural Regions: Creating Unity in Diversity? In The New European Frontiers: Social and Spatial (Re)Integration Issues in Multicultural and Border Regions; Bufon, M., Minghi, J., Paasi, A., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- European Outline Convention on Transfrontier Co-Operation between Territorial Communities or Authorities, Madrid, 21.V.1980, European Treaty Series—No 106. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/0900001680078b0c (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Sousa, L.D. Understanding European Cross-border Cooperation: A Framework for Analysis. J. Eur. Integr. 2013, 35, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokkola, E.-K. Cross-border regionalization, the INTERREG III A initiative, and local cooperation at the Finnish—Swedish border. Environ. Plan. 2011, 43, 1190–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbe, J.; Ramirez, M.G. AEBR and EGTC—A Long Way to Success, in Legal Setup for Cooperation: EGTC and More, Newsletter Interact, AEBR. 2013. Available online: http://www.interact-eu.net/downloads/7685/Newsletter_INTERACT_Winter_2013_legal_setup_for_cooperation_EGTC_and_more.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Morata, F. Euroregions and European integration. Doc. Anal. Geogràfica 2010, 56, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Terlouw, K. Border surfers and Euroregions: Unplanned cross-border behaviour and planned territorial structures of cross-border governance. Plan. Pract. Res. 2012, 27, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euroregion Beskidy. Available online: http://www.euroregion-beskidy.pl/euroregion-beskidy-2/o-euroregionie/ (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Strategia Rozwoju Euroregionu Beskidy na Lata 2016–2023. Maj 2016. Available online: http://www.euroregion-beskidy.pl/mikroprojekty/interreg-pl-cz/strategia-rozwoju-euroregionu-beskidy-2016-2023/ (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Howaniec, H. Rola Klastrów w Rozwoju Lokalnym na Przykładzie Klastra Energetycznego i Klastra Euroregion Beskidy. Studia Mater. Misc. Oeconomicae 2013, 1, 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Komisja Europejska, Pokonywanie Przeszkód w Regionach Przygranicznych. Podsumowanie Wyników Internetowych Konsultacji Społecznych. 21 Września–21 Grudnia 2015 r.; Dyrekcja Generalna ds. Polityki Regionalnej i Miejskiej, Luxembourg. April 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/consultation/overcoming-obstacles-border-regions/results/overcoming_obstacles_pl.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2019).

- Wróblewski, Ł.; Dziadzia, B.; Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z. Sustainable management of the offer of cultural institutions in the cross-border market for cultural services-barriers and conditions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dołzbłasz, S.; Raczyk, A. The role of the integrating factor in the shaping of transborder co-operation: The case of Poland. Quaest. Geogr. 2010, 29, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dołzbłasz, S. Cross-Border Co-Operation in the Euroregions at the Polish-Czech and Polish-Slovak Borders. Eur. Ctries. 2013, 5, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranking Polskich Miast Zrównoważonych, Arcadis: Poland. 2017. Available online: https://www.arcadis.com/media/6/0/D/%7B60DA8546-A735-430A-BF9A-6114B0362FD7%7DRanking%20Polskich%20Miast%20Zrownowazonych%20Arcadis%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Wałachowski, K.; Uciekające Metropolie. Ranking 100 Polskich Miast; Klub Jagielloński: Kraków. 2019. Available online: https://klubjagiellonski.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/uciekajace-metropolie.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Morata, F.; Noferini, A. The Pyrenees-Mediterranean Euroregion: Functional networks, actor perceptions and expectations. In Europe’s Changing Geography: The Impact of Inter-Regional Networks; Bellini, N., Hilpert, U., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

| Specification | Research |

|---|---|

| Research method | Survey |

| Research technique | PAPI (paper and pen personal interview) CAWI (computer-assisted web interview) |

| Research tool | Paper questionnaire Electronic questionnaire |

| Sample selection | Targeted (residents of Beskydy Region, Polish side) |

| Sample size | Surveys distributed: 400 in total (without online surveys) (0.029% of the total population of Euroregion Beskydy; 0.047% of Polish side of Euroregion Beskydy) Surveys for calculations: 220 (0.016% of the total population of Euroregion Beskydy; 0.026% of Polish side of Euroregion Beskydy) |

| Spatial extent of research | Poviats: Bielsko, Pszczyna, Żywiec (Silesian Voivodeship), Oświęcim, Suski (Lesser Poland Voivodship) |

| Research date | June 2019–June 2020 |

| Gender | Female | Male | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | 50 | 50 | ||

| Age | Under 25 years | From 26 to 40 years | From 41 to 55 years | Over 56 years |

| (%) | 32 | 27 | 37 | 4 |

| Education | Primary/Middle school | Vocational school | High school education | A university degree |

| (%) | 0 | 2 | 22 | 76 |

| Place of residence | Village | City under 50,000 residents | A city from 50 to 100,000 residents | A city of over 100,000 residents |

| (%) | 35 | 18 | 12 | 35 |

| The Area of Rating | Very Low | Rather Low | Middle | Rather High | Very High | I Have No Opinion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| transport availability | 2 | 12 | 27 | 32 | 3 | 23 |

| quantity and quality of labor resources | 3 | 14 | 28 | 23 | 6 | 26 |

| labor costs | 0 | 12 | 35 | 13 | 5 | 35 |

| market absorption | 0 | 7 | 32 | 25 | 5 | 30 |

| level of development of economic infrastructure | 1 | 9 | 31 | 31 | 5 | 22 |

| level of development of social infrastructure | 0 | 7 | 32 | 30 | 4 | 26 |

| level of economic development | 0 | 10 | 33 | 28 | 6 | 23 |

| condition of the natural environment | 2 | 17 | 22 | 24 | 13 | 21 |

| level of public security | 0 | 7 | 25 | 30 | 11 | 25 |

| region’s activity towards investors | 1 | 8 | 31 | 20 | 8 | 31 |

| The Area of Rating | Very Low | Rather Low | Middle | Rather High | Very High | I Have No Opinion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| transport availability | 1 | 8 | 27 | 28 | 5 | 30 |

| quantity and quality of labor resources | 0 | 10 | 26 | 20 | 6 | 37 |

| labor costs | 3 | 12 | 27 | 14 | 2 | 42 |

| market absorption | 0 | 9 | 26 | 19 | 5 | 40 |

| level of development of economic infrastructure | 1 | 7 | 25 | 27 | 7 | 33 |

| level of development of social infrastructure | 0 | 7 | 25 | 28 | 9 | 31 |

| level of economic development | 0 | 7 | 25 | 28 | 9 | 31 |

| condition of the natural environment | 4 | 10 | 29 | 19 | 7 | 32 |

| level of public security | 1 | 8 | 26 | 26 | 8 | 31 |

| region’s activity towards investors | 0 | 5 | 26 | 24 | 7 | 38 |

| Entity | Definitely Positive | Rather Positive | Neither Positive Nor Negative | Rather Negative | Definitely Negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| local authorities | 5 | 31 | 58 | 5 | 0 |

| business | 5 | 34 | 57 | 3 | 0 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Howaniec, H.; Lis, M. Euroregions and Local and Regional Development—Local Perceptions of Cross-Border Cooperation and Euroregions Based on the Euroregion Beskydy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187834

Howaniec H, Lis M. Euroregions and Local and Regional Development—Local Perceptions of Cross-Border Cooperation and Euroregions Based on the Euroregion Beskydy. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187834

Chicago/Turabian StyleHowaniec, Honorata, and Marcin Lis. 2020. "Euroregions and Local and Regional Development—Local Perceptions of Cross-Border Cooperation and Euroregions Based on the Euroregion Beskydy" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187834

APA StyleHowaniec, H., & Lis, M. (2020). Euroregions and Local and Regional Development—Local Perceptions of Cross-Border Cooperation and Euroregions Based on the Euroregion Beskydy. Sustainability, 12(18), 7834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187834