1. Introduction

Consumer socialization theory has been used across many disciplines to provide a theoretical foundation for exchange-based relationships [

1]. The theory suggests that consumer socialization behavior is based on individual attitudes and support and benefits, where individuals who perceive more significant benefits engage in more supportive social interaction behavior [

2]. Also, conventional socialization occurs among consumers who know one another, such as parents and children, colleagues, relatives, friends, and neighbors (e.g., peers are widely acknowledged as critical forces affecting consumer socialization) [

3]. Meanwhile, the rapidly evolving epidemic has stressed the entire sports industry economically, especially in sports events (e.g., marathon running). Moreover, marathon running has a documented social impact and an economic impact, and health-enhancing behavior and scholars have supported a need for developing events [

3].

Notably, the successful development and execution of events often rely on consumer participation and advocacy; studies have documented that social interaction may increase consumer and other stakeholders’ marathon running development and promotion [

4,

5,

6]. Besides, many researchers have studied consumer perceptions and attitudes [

6,

7,

8], although most have done so in the context of mega-events such as the Olympics, World Cup games, and international expositions. However, the influence of social interaction through marathon events on consumer socialization behaviors has rarely been investigated [

4,

5,

6,

7]. To fill this gap, we investigated consumption-related intergenerational influences, peer influences, and traditional media through social interaction and its impacts on consumer socialization behavior from a consumer socialization perspective. In particular, we suggest that marathon running can be a sustainable and consistent form of sports event development [

1].

Also, consumers are influential attendees of marathon running [

1,

9], and can positively contribute to social network development and benefit event cohesion through their interaction or other consumer networks [

10]. Thus, understanding consumer behavior as loyal customers or advocates of an event is a fundamental strategy for a marathon running success and building social networks for its sustainability. Further, marathon running may not allocate appropriate financial resources in marketing to sustain the event. Therefore, consumer social networks can be an essential event ambassador. Various benefits have been emphasized related to consumer support, significantly personal benefits. Therefore, this study pays attention to consumer perceptions of and attitudes toward hosting a sustainable marathon running.

Unfortunately, studies based on the consumer socialization theory have not provided a sufficient explanation for consumer support of marathon running development [

11,

12]. Such arguments suggest relying on the costs and benefits [

13,

14] and the benefits to consumer conformity behavior in explaining consumer support for marathon running. Moschis and Churchill [

15] indicated the limitations of consumer socialization theory to explain citizens’ attitudes and support toward events and claimed that consumers consider more diverse benefits and costs (e.g., economic, environmental, and social benefits/costs) as personal or collective benefits over time.

Given the advantages that consumer participants’ support and advocacy bring to the success and sustainability of a marathon running, this study aims to explore consumer socialization behaviors, specifically the conformity effects of event participant consumer socialization (namely, intergenerational influences, peer influences, and traditional media) to the running behavior of event-participating consumers. Therefore, it is essential to clarify consumer socialization behaviors on event marathon running behavior in a physical education domain. It will contribute to the literature in various ways by exploring the interaction effects of three types of consumer socialization models on running behavioral outcomes.

2. Theoretical Review

Marathon running is a popular leisure activity and community event that has expanded dramatically in recent years [

2]. Hosting a small-scale marathon running offers various benefits for both the hosting community and participants, including direct economic effects on the community [

1,

2]. Therefore, influential events like annual marathons create economic benefits and foster sustainable marathon running development. Considering the three pillars of sustainable marathon running (namely, intergenerational influences, peer influences, and traditional media), Moore, Wilkie, and Lutz [

16] demonstrated that small-scale sporting events might be a viable form of sustainable development. Recurring sports events like the marathon running can be a sustainable and consistent form of sports event development because of the variety of benefits to both the hosting community and participants [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Running as a leisure activity has many direct and indirect benefits, including quality of life improvement through participating in events and psychological involvement in physical activity [

1,

3,

12]. Marathon running has also become a popular sustainable sport event providing substantial social value to leisure activity [

11,

12].

Parents play a significant role in children’s consumer socialization, but little is known about differences in parents’ consumer socialization tendencies. This study examines the thesis that these tendencies can predict parents’ general socialization styles (e.g., intergenerational influences) [

6,

7]. Most consumer socialization research examining family influences has focused on overt interaction processes (communication about consumption in particular) [

12,

17,

18]. Such studies have investigated how the quantity of such interactions affects consumption-related properties. Studies incorporating reinforcement processes are almost nonexistent.

On the other hand, peers play a considerable role in physical activity [

9,

19]. To develop a peer network on campus, students immerse themselves in the social environment [

18]. Furthermore, prior literature generally supports the notion that social interactions are a central component of leisure-based physical activity [

12]. This is because the activity becomes embedded into the fabric of everyday life, and thereby could allow participants to enhance their social connections through interactions with others. Thus, the influencing individuals’ participation in physical activities and mass sporting events are noteworthy and must be further explored.

Also, in considering information search behavior, media richness is a significant characteristic in that it contributes to satisfying information needs [

20]. Research has shown that traditional media’s unique, authenticity nature is influential in developing interactive processes and heightening interaction involvement [

2]. Other research found that media’s informational use significantly correlated to actual engagement toward activity [

21]. While no evidence of a direct link between consumer socialization behaviors and marathon running has shown in sport management, this work in other disciplines provides a basis for further inquiry. Indeed, understanding how consumer socialization behaviors involvement affects marathon running behavior with one’s conformity could inform the sports industry’s methods. Specifically, managers may gain insight into the underlying reasons for participation in marathon running, which could aid them in recruitment and marketing efforts for programs and events.

Consistent with the literature reviewed above, we have formulated three specific hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Intergenerational influence is positively associated with event marathon running behavior.

Hypothesis 2. Peer influence is positively associated with event marathon running behavior.

Hypothesis 3. Traditional media is positively associated with event marathon running behavior.

The existing literature on sports events development and consumer socialization behavior has consistently demonstrated that consumers who perceive great benefit from sports events development showed more positive consumer behavior attitudes toward sports events [

22,

23,

24]. However, consumers do not perceive the effects of sports events identically, as these perceptions may depend on personal circumstances and involvement with the event. Ok et al. [

3] emphasized the importance of assessing from different angles to understand better consumer perceptions of the effects of sports events (e.g., consumer socialization behavior). Their study was based on consumer socialization theory to gain a general view of consumer perceived effects of a mega-event. Therefore, consumer socialization event attendees and non-consumer socialization attendees may have different perceptions of event effects.

Conformity is a common phenomenon among people in social networks [

2,

3]. For example, conformity consumption will influence others’ evaluations and be driven by other people’s behavior [

3]. Although many theoretical, empirical, and experimental studies, particularly in psychology and sociology, have investigated the presence of conformity observations about human society, there are few works investigating conformity in the sports events of social networks (e.g., the event of marathon running). In this light, we examined the effect of consumers’ conformity on social networks’ sports events.

Further, it is proposed that event affective conformity moderated the relationship between consumer socialization behavior and marathon running advocacy because customer intentions to be strong advocates are created by consumer socialization-based conformity behaviors, which exist as the result of customer behavior conformity. An empirical study showed that consumer socialization behavior at a marathon running is likely to create conformity behavior to the event and ultimately contribute to the marathon running developed [

25]. Consumers who are satisfied with their participation in the marathon running will more effectively committee and, in turn, advocate the event. Therefore, we consider moderating the effects of consumer socialization behavior on event marathon running behavior.

Consistent with the literature reviewed above, we have formulated three specific hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4. Conformity moderates the effect of event intergenerational influences on event marathon running behavior.

Hypothesis 5. Conformity moderates the effect of event peer influences on event marathon running behavior.

Hypothesis 6. Conformity moderates the effect of event traditional media on event marathon running behavior.

5. Discussion

This study examined the effect of consumer socialization behavior evaluations of a marathon running on their advocacy of the sporting event with conformity behavior as a mediator and three types of influenced benefits as moderators. Consumer socialization (namely, intergenerational influences, peer influences, and traditional media) positively affected event marathon running behavior. The findings show that consumer socialization behavior benefits more in the marathon event road running behavior [

2].

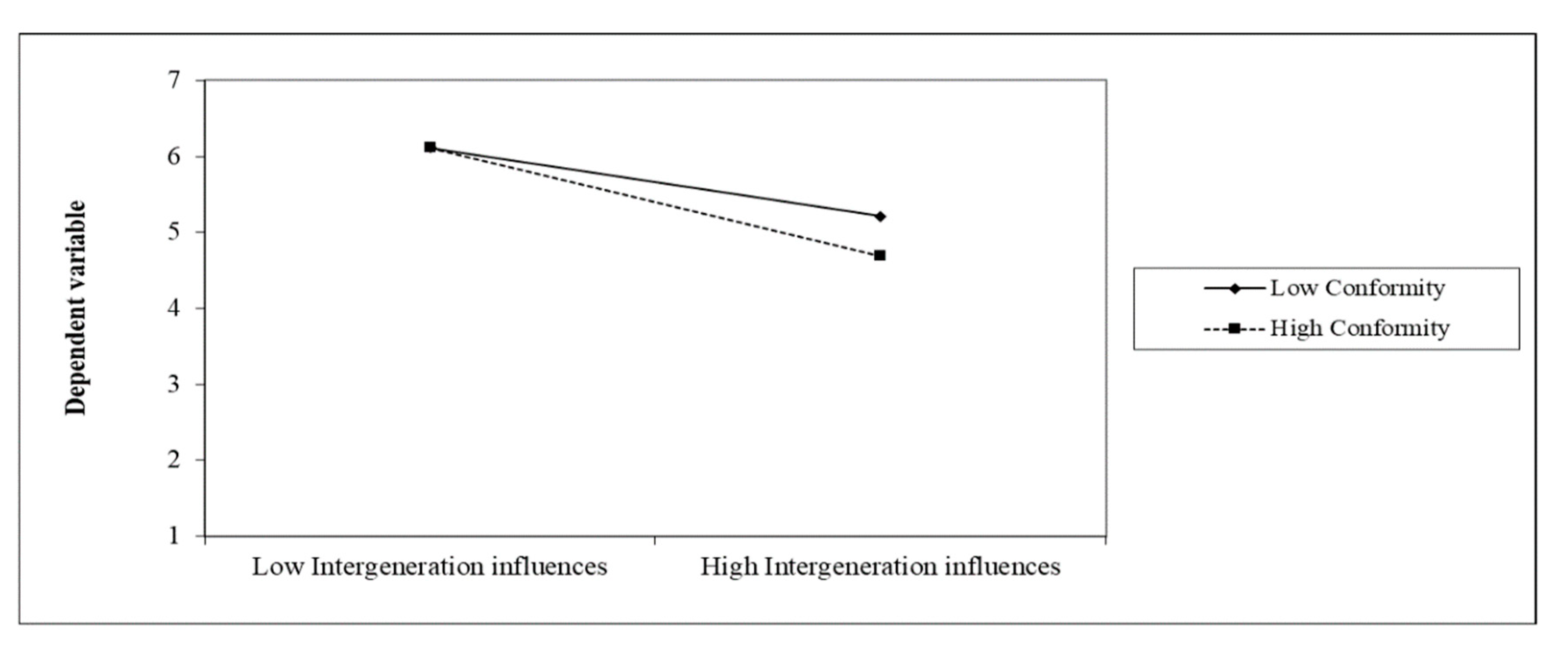

This study found that conformity benefit moderates the effect of intergenerational influences on marathon running behavior. Although participants’ event advocacy was high when they were consumers regardless of the conformity, intergenerational influences advocacy was particularly low among fewer conformity participants. Among low conformity groups, event advocacy was significantly higher when intergenerational influences were high. The significant interaction effect between intergenerational influences and conformity on marathon running behavior advocacy suggests that when intergenerational consumer influence on the marathon running is relatively low, conformity makes a difference in their event advocacy [

31]. Finally, the results also showed that conformity affects consumers’ intergenerationally influenced and marathon running behavior in consumer socialization, especially in small-sports events. The impact will be increasingly significant as the scale of the conformity networks gradually becomes more massive.

Previous research mainly focused on two consumer socialization agents: school and peers [

12,

17]. Our findings’ primary contribution to theory is that consumption-related event marathon running behavior through social interaction is becoming increasingly relevant for consumer socialization issues and can significantly influence newcomers’ attitudes toward consumers’ behavior engaged in marathon running. By incorporating more variables into the socialization framework [

7,

12], we have created a model that describes socialization processes in the consumption of marathon running. Perhaps most importantly, our finding that social interaction drives consumer behavior through conformity and informational routes extends the socialization framework proposed. Our findings suggest that the social learning process in marathon running remains a complex process that features multi-level variables, beyond traditional socialization theory. Marketing researchers should build their future research plans accordingly, such that consumer socialization behavior is dynamic and multi-level [

3,

12], so future studies can collect longitudinal data to find out the dynamic developing laws of consumer socialization behavior-specific marathon running.

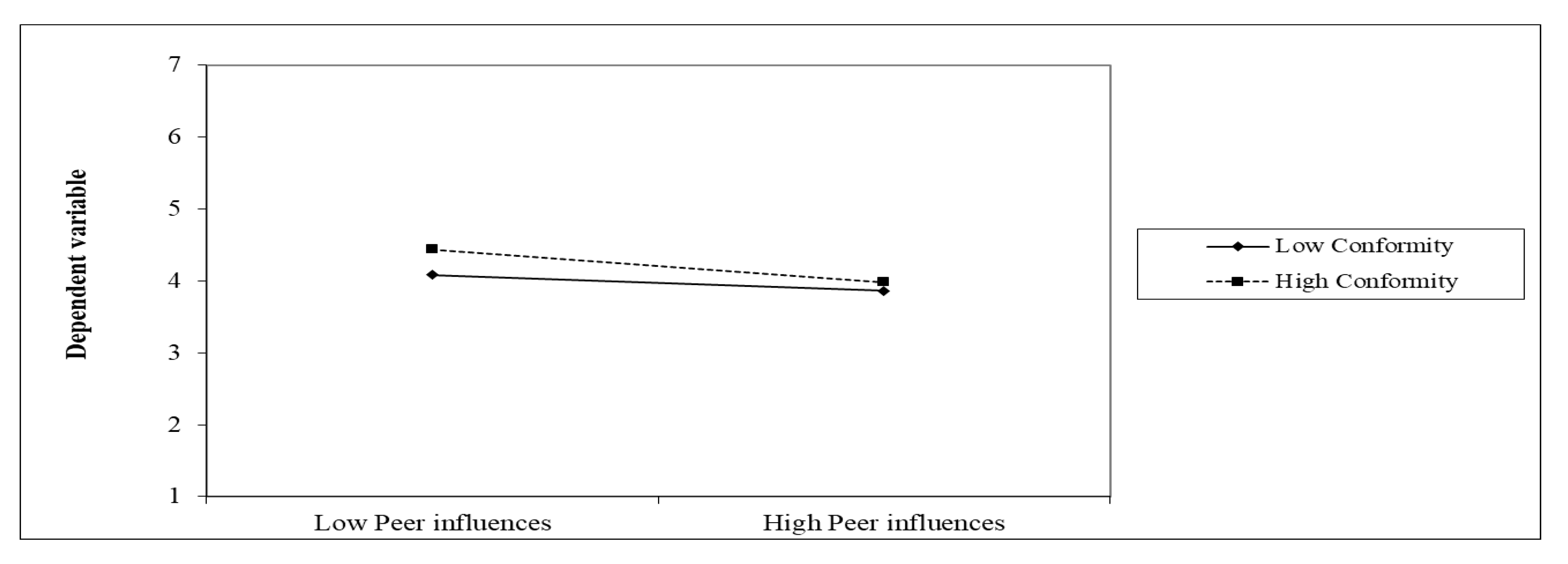

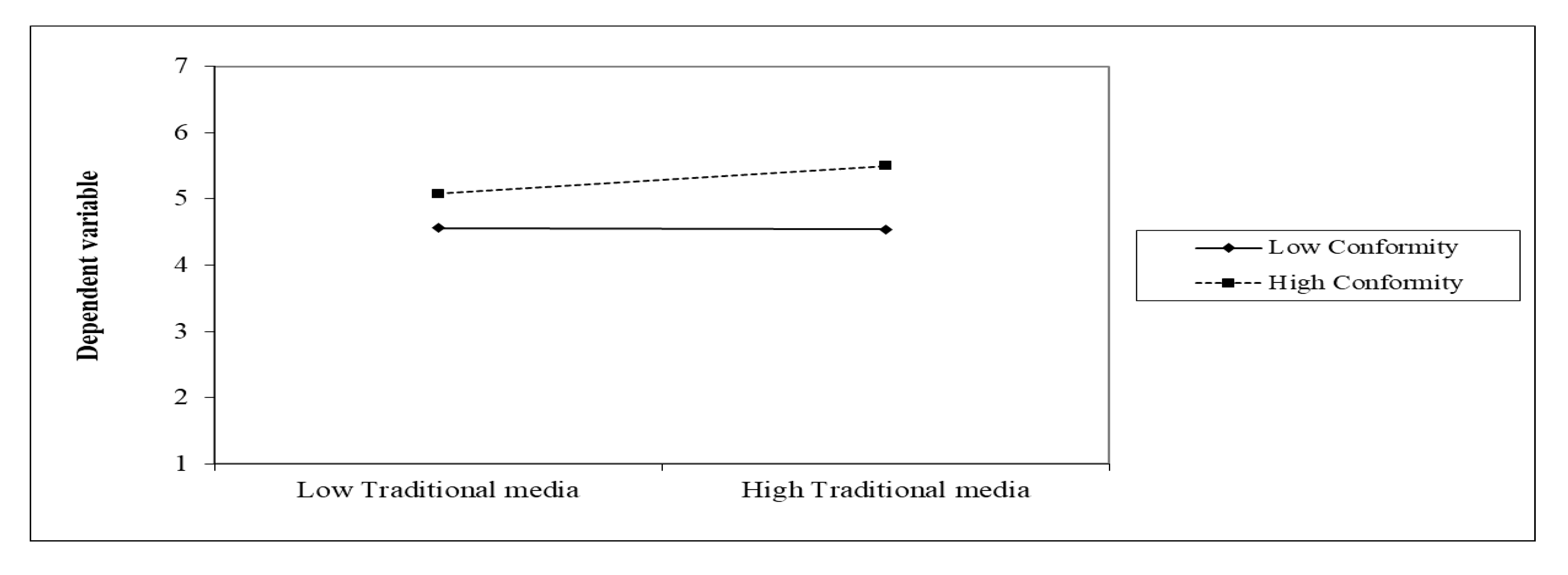

In addition, this study did not observe peer influences and traditional media on moderated function. The insignificant moderated mediation effects of peer-influenced and traditional media on marathon event road running behavior do not necessarily mean that they are unimportant. Instead, the results indicate that the effect of peer-influenced and traditional media on marathon event road running behavior through consumer socialization is not conditional. In other words, the direct and indirect effects of peer-influenced and traditional media lead event consumer behavior to the event regardless of the conformity behavior [

4,

9,

19]. Specifically, this study observed a significant direct effect of peer-influenced and traditional media function of marathon event road running behavior. When consumers participating in an event are both peer-influenced and traditional media influenced, they become more committed to the marathon running, thus leading to running behavior advocacy. Findings suggested meaningful discussion and implications for academics and practitioners related to the two types of benefits. For example, through marathon running participation, they help academics and practitioners determine what motivates consumer socialization behavior.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the study findings contribute to the literature and provide meaningful implications for various stakeholders in consumer socialization behavior, this study is not free of limitations. First, this study is also limited in its generalizability because the collected data is from a single marathon running. This study is also limited because the collected data is from a single local marathon running. Also, event participants and non-participants may experience socialization behaviors differently. The authors believe that a longitudinal research study may inspire a meaningful discussion of implementing different programs to gain more support from various stakeholders. Second, the study results may have been due to different features of sports events. Future research could exploit different sports events to explore the effect of consumer socialization behaviors on the dynamic changes in conformity behavior. Finally, the self-reported data might inflate our research variables’ relationship because of common method variance [

26]. Future research should address this issue by using objective measurements or field experiments.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study support the idea that social interaction may influence consumer behavior of engaging in marathon running. Meanwhile, our support conformity moderated the relationship between intergenerational influence and marathon running behavior in marathon events. We believe that critical findings can be used in future research to advance our understanding of consumer socialization constructed of consumers’ support in sports marketing. In addition, we believe that marketers should promote consumers’ socialization behaviors when they grasp it, which may produce various positive behaviors outcomes.

In summary, our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we expand the understanding of social interaction by investigating whether the context-specific variables of intergenerational influences, peer influences, and traditional media are associated with running behavior in marathon events. Second, the possibility that intergenerational influences can shape individuals’ consumer socialization behavior acquired from marathon events, peer-influences, and traditional media was tested, providing practical insights for consumer behaviors. Third, we recognize the effects of consumer socialization behavior, an essential topic in physical education literature [

2].

Overall, this study highlights the importance of consumer socialization behavior in the sports context. Different social interaction status might shape individual consumer socialization behavior, and multiple methods are warranted to uncover the role of social interaction in PE. The present study opens a new avenue in understanding the effects of consumer socialization behavior and marathon events. However, this is just a beginning in PE as the study’s conclusions are preliminary, and this speculation requires further investigation.