Application of Ecosophical Perspective to Advance to the SDGs: Theoretical Approach on Values for Sustainability in a 4S Hotel Company

Abstract

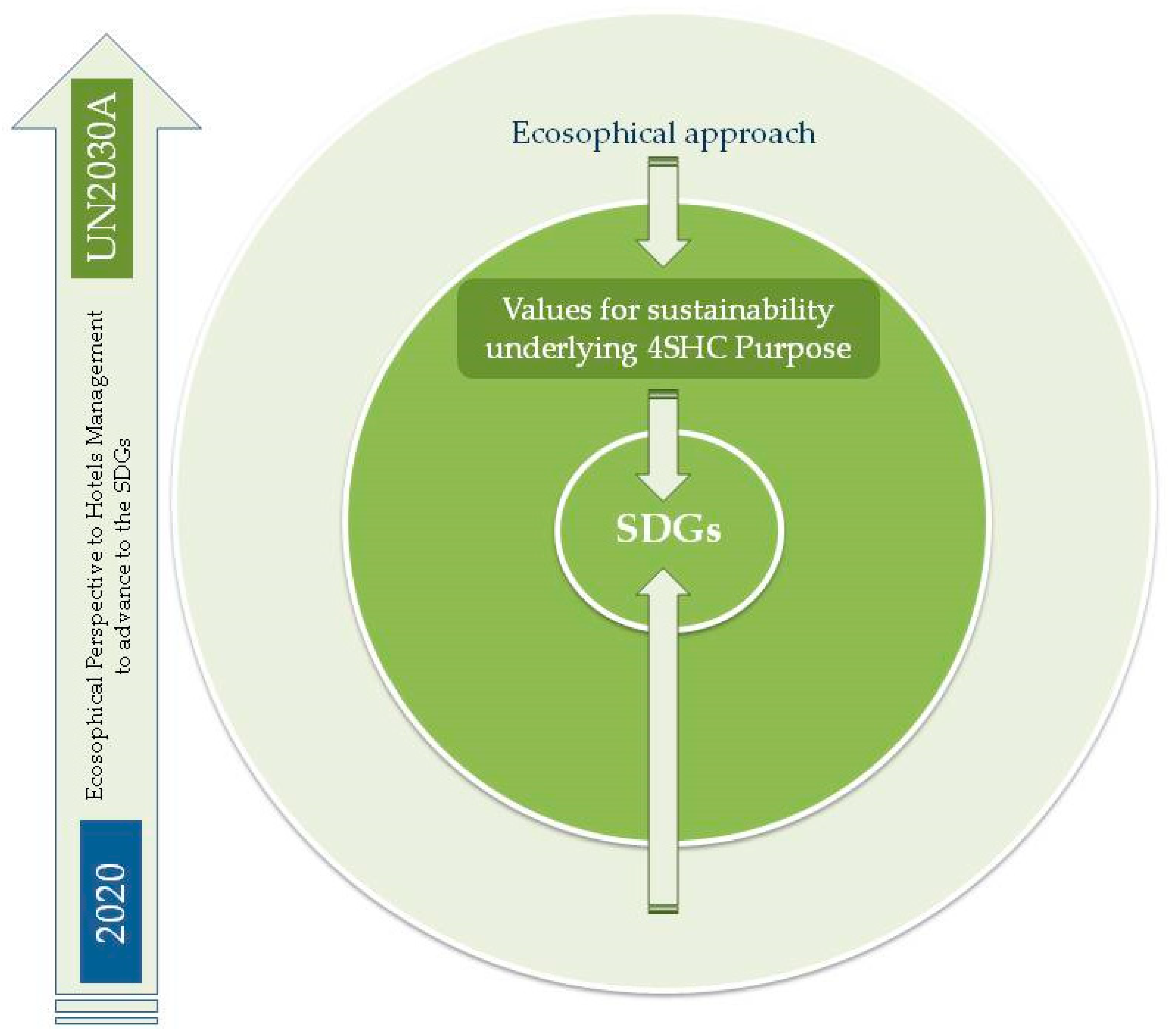

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

- Phase 1: Theoretical framework definition and 4S-SM-HC selection. In this first phase, developed during September and October 2019, we began by defining the theoretical framework. Then, an exhaustive Desk Research among hotel companies of the Fourth Sector was carried out to select the 4S-SM-HCs, for which three parameters were defined. The first is to have a transformative purpose that transcends purely economic objectives [120], committing itself equally to the generation of positive social and environmental impacts [121]. In this case, the chain’s purpose declares that “we are a hotel company focused on achieving the wellbeing of people and the planet through unforgettable experiences, a business with a soul that wants to generate relevant impacts for its clients, stakeholders and employees” [120]. The second is that it is a SMEs, according to the definition provided by the OECD [54], and indeed, the company has less than 250 employees distributed among its headquarters and the hotels it manages. The third and final parameter is that, based on their Purpose, they demonstrate a strong willingness to contribute effectively to SDGs by developing sustainability policies in line with UN2030A [29] (under development in phase 2 of the research). After examining, contrasting, verifying, and selecting the 4S-SM-HCs, the research team held two consecutive meetings with the management team of the selected 4S-SM-HCs with two objectives: (1) to gain an in-depth understanding of the internal reflection process that they followed for more than two months, which culminated in the definition of their purpose; (2) to ascertain that their business objectives are threefold, thus verifying that they are a 3BL company [107,108]. Data implicit in the context were included in the analysis of the results, to avoid potential limitations of this analysis [122]. This phase ended with the selection of the 4S-SM-HCs, once verified that they met the criteria.

- Phase 2: Focus group design. Developed during November 2019, the profile definition and selection of the participants in the focus group discussion (FG) was carried out. The decision as to the number of participants and their profile was based on three criteria: the high degree of knowledge and involvement of the participants in the definition of the company’s purpose; the decision-making capacity and high degree of responsibility to implement and carry it out successfully; and the non-iteration of data. The participants selected to participate in the FG were the four members of the Board of Directors—the most senior managers within the hotel company—three of whom are also shareholders in the 4S-SM-HCs. Table 1 describes the participants’ profile, the position they hold in the 4S-SM-HCs, and their contribution, whether in the purpose definition (PD) or in the SSMM implementation (SSMMI).

- Phase 3: Data collection. A semi-structured FG was carried out as a data collection technique by performing a single FG [123]. This third phase took place during December 2019 and was carried out at the company’s headquarters in Tenerife, which facilitated the creation of a climate of trust and security among the participants that favored participation and complicity among them. The duration of the FG was two hours and twenty-five minutes. Video and audio images were recorded in duplicate, and only audio was recorded in order to ensure the quality of the recordings and facilitate the transcription of the audios, as well as having a secure backup. FG was conducted in the mother tongue of the participants (Spanish), and then the content was transcribed into the original language in which it was developed and recorded. Finally, the translation into English was done to present the results of this research.

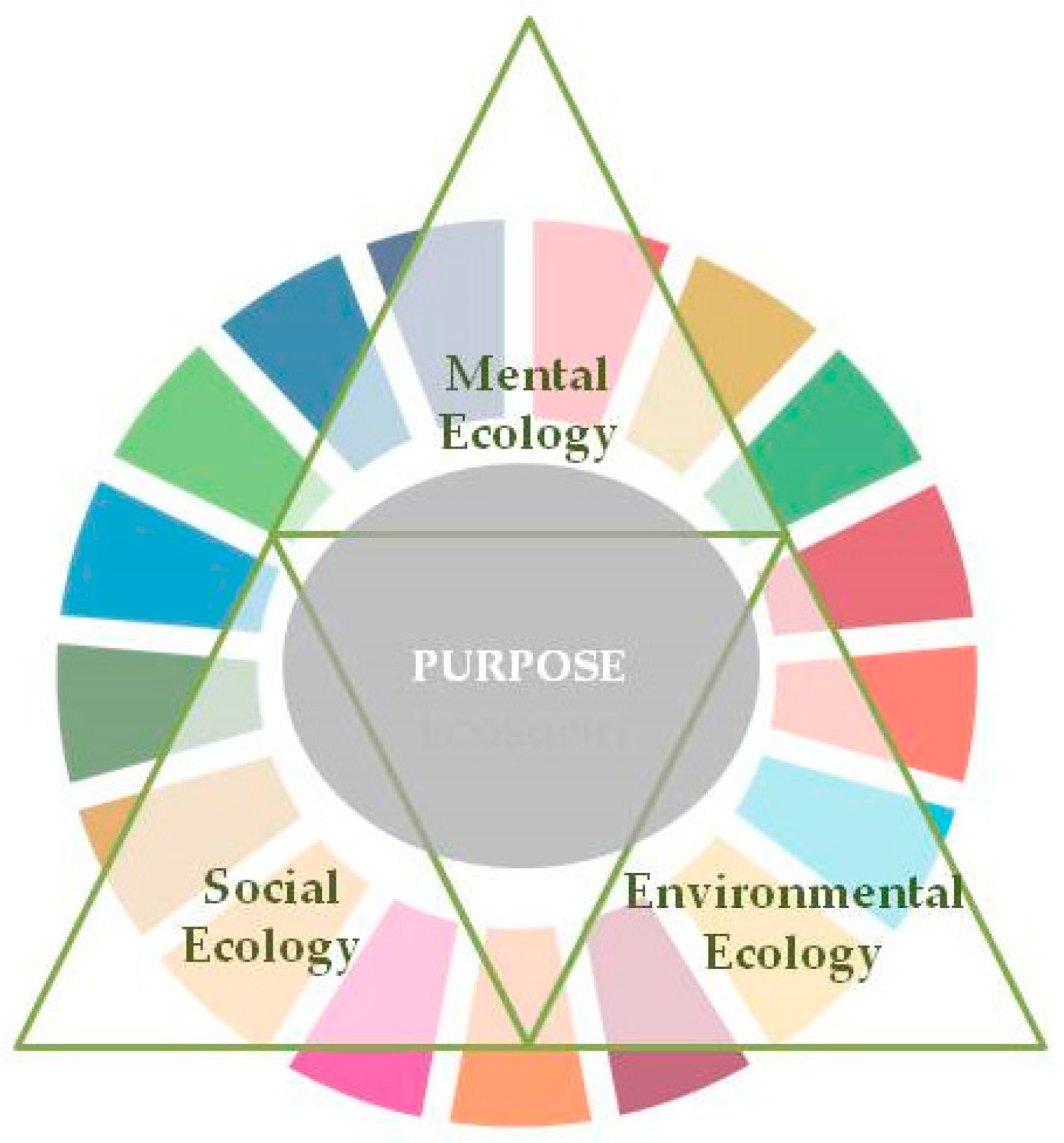

- Phase 4: Data Analysis. Thematic Analysis is carried out to extract the data in the FG. This analysis is considered the most appropriate by the research team as it allows them to extract, analyze, and code the data obtained and then associate them around the same subject. Developed over January and February 2020, the thematic analysis allows for the examination, comparison, and analysis of the data extracted from the transcripts in six correlative phases [124]: data knowing, in which several listenings and readings are carried out before and after the transcriptions in order to become familiar with the different topics addressed; data coding, where common data are structured and associated around specific topics; revision of the topics and verification of their correct assignment; topics defining and naming, providing information on all the topics that arose during the FG; and report producing, to select the most relevant extracts that serve the three central themes (mental, social and environmental) that are the subject of this research.

- Phase 5: Results. The results were collected between March and April 2020. Afterward, they were classified in three blocks according to ecosophical criteria and the interrelationship established with the 5Ps that conform the SDGs [17], and thus, providing the ecosophical vision and the SDGs perspective proposed as an objective of this research. In this way, it is proposed to the participants in the FG that they reflect first on the contributions that their purpose makes from Mental Ecology to the SDGs area of People. Secondly, they were asked to make contributions to Social Ecology and how the purpose contributes to three areas of the SDGs (Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership). Finally, they were asked to contribute reflections on Environmental Ecology and how their purpose contributes to the SDGs Area of Planet.

4. Results

4.1. Reflections on Mental Ecology and Its Correlation with “People” as an SDGs Area: Which Values for Sustainability Does the Purpose Bring to the SSMM to Enhance People’s Wellbeing

4.2. Reflections on Social Ecology and Its Correlation with “Prosperity, Peace and Partnership” as SDGs Areas: Which Values for Sustainability Does the Purpose Bring to the SSMM to Contribute to the Wellbeing and Prosperity of the Community?

4.3. Reflections on Environmental Ecology and Its Correlation with “Planet.” as an SDGs Area: Which Values for Sustainability Does the Purpose Bring to the SSMM to Help Make the Planet. Better?

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, M.; Babiker, M.; Chen, Y.; de Coninck, H.; Connors, S.; van Diemen, R.; Dube, O.P.; Ebi, K.L.; Engelbrecht, F.; Ferrat, M.; et al. IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Res; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Global Warming of 1.5 °C. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Raven, P.H. Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13596–13602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sixth Mass Extinction of Wildlife Accelerating, Scientists Warn|Environment|The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jun/01/sixth-mass-extinction-of-wildlife-accelerating-scientists-warn (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Refugiados Climáticos| ACNUR. Available online: https://eacnur.org/es/actualidad/noticias/emergencias/refugiados-climaticos (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Why 2020 to 2050 Will Be ‘the Most Transformative Decades in Human History’|by Eric Holthaus|Jun, 2020 |OneZero. Available online: https://onezero.medium.com/why-2020-to-2050-will-be-the-most-transformative-decades-in-human-history-ba282dcd83c7 (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Neira, M.; World Health Organization. Department of Public Health, Environmental and Social Determinants. Our Lives Depend on a Healthy Planet. Available online: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/commentaries/healthy-planet/en/ (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Macrotrends and Disruptions Shaping 2020–2030; World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Biodiversidad|El Tráfico de Animales y la Deforestación Podrían Causar la Próxima Pandemia—El Salto—Edición General. Available online: https://www.elsaltodiario.com/biodiversidad/tráfico-animales-deforestación-pueden-acercar-humanos-próxima-pandemia (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- How Modern Life Became Disconnected from Nature. Available online: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_modern_life_became_disconnected_from_nature (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australas. Psychiatry 2007, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsini, S.; Mills, J.; Usher, K. Solastalgia: Living with the environmental damage caused by natural disasters. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2014, 29, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Mauchigna, L.; Marinoni, G.L.; Zamperini, A.; Bucuță, M.; Dima, G. Solastalgia’s mourning and the slowly evolving effect of asbestos pollution: A qualitative study in Italy. Heliyon 2019, 5, e03024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solastalgia: The Distress Caused by Environmental Change. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18027145/ (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Fuentes, L.; Asselin, H.; Bélisle, A.C.; Labra, O. Impacts of environmental changes on well-being in indigenous communities in eastern Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qué son la Solastalgia, el Trastorno de Déficit de Naturaleza y Otros Desordenes del Nuevo Milenio. BBC News Mundo. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-38136747 (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- La Agenda 2030, ¿crónica de un Fracaso Anunciado?—El Orden Mundial—EOM. Available online: https://elordenmundial.com/agenda-2030-cronica-de-un-fracaso-anunciado/ (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. Sustainable Development Report 2019. Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Devleopment Goals; Bertelsmann Stiftung: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Earth Charter Commission. The Earth Charter. 2000, p. 4. Available online: https://earthcharter.org/about-us/earth-charter-commission/ (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Earth Charter. Available online: https://earthcharter.org/read-the-earth-charter/ (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Coscieme, L.; Sutton, P.; Mortensen, L.F.; Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Trebeck, K.; Pulselli, F.M.; Giannetti, B.F.; Fioramonti, L. Overcoming the Myths of Mainstream Economics to Enable a New Wellbeing Economy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frugoli, P.A.; Almeida, C.M.V.B.; Agostinho, F.; Giannetti, B.F.; Huisingh, D. Can measures of well-being and progress help societies to achieve sustainable development? J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 90, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, P.; Chassagne, N. Post COVID-19 ecological and social reset: Moving away from capitalist growth models towards tourism as Buen Vivir. Tour. Geogr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Does a Wellbeing Economy Look Like? Available online: http://www.smart-development.org/what-does-a-wellbeing-economy-look-like (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Wellbeing Economy Alliance. The Business of Wellbeing—A Guide to the Alternatives to Business as Usual. Wellbeing Economy Alliance, 2020. Available online: https://wellbeingeconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/The-Business-of-Wellbeing-guide-Web.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- Wellbeing Economy Alliance—Building a Movement for Economic System Change. Available online: https://wellbeingeconomy.org/ (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- WEAll Citizens. Available online: https://wellbeing-economy-alliance-trust.hivebrite.com/ (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Rubio-Mozos, E.; García-Muiña, F.E.; Fuentes-Moraleda, L. Rethinking 21st-century businesses: An approach to fourth sector SMEs in their transition to a sustainable model committed to SDGs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Results-Oriented and People-Centered UN|Sustainable Development Goals Fund. Available online: https://www.sdgfund.org/results-oriented-and-people-centered-un (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The Limits to Growth. A Report for The Club of Rome’s Projecton the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 0-87663-165-0. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, D.W.; Fanning, A.L.; Lamb, W.F.; Steinberger, J.K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home—A Good Life For All within Planetary Boundaries. Available online: https://goodlife.leeds.ac.uk/ (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Vandenhole, W. De-growth and sustainable development: Rethinking human rights law and poverty alleviation. Law Dev. Rev. 2018, 11, 647–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meet the Doughnut: The New Economic Model That Could Help end Inequality|World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/04/the-new-economic-model-that-could-end-inequality-doughnut/ (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Doughnut Economics: Economics for a Changing Planet—Stockholm Resilience Centre. Available online: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-videos/2018-09-24-doughnut-economics-economics-for-a-changing-planet.html (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Raworth, K. Doughnut|Kate Raworth. Available online: https://www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/ (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Chassagne, N.; Everingham, P. Buen Vivir: Degrowing extractivism and growing wellbeing through tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1909–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ims, K.J. Quality of life in a deep ecological perspective. The need for a transformation of the western mindset? Soc. Econ. 2018, 40, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivielso, J.; Moranta, J. The social construction of the tourism degrowth discourse in the Balearic Islands. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-Salom, M.; Blanco-Romero, A.; Vera-Rebollo, F.; Ivars-Baidal, J. Territorial tourism planning in Spain: From boosterism to tourism degrowth? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvensivu, P. Transforming market-nature relations through an investigative practice. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 95, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchs, M.; Koch, M. Challenges for the degrowth transition: The debate about wellbeing. Futures 2019, 105, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.; MurrayMas, I.; Blanco-Romero, A.; Blázquez-Salom, M. Tourism and degrowth: An emerging agenda for research and praxis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1745–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 and the Transition to a Sustainable Wellbeing Economy—The Solutions Journal. Available online: https://www.thesolutionsjournal.com/article/covid-19-transition-sustainable-wellbeing-economy/ (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Wellbeing Economy Governments WEGo—Wellbeing Economy Governments. Available online: http://wellbeingeconomygovs.org/ (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- New Zealand Government. The Treasury Measuring Wellbeing: The LSF Dashboard. Available online: https://treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz-economy/living-standards/our-living-standards-framework/measuring-wellbeing-lsf-dashboard (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Graham-McLay, C. New Zealand’s Next Liberal Milestone: A Budget Guided by ‘Well-Being’. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/22/world/asia/new-zealand-wellbeing-budget.html (accessed on 2 August 2019).

- Aingeroy, E. New Zealand’s World-First ‘Wellbeing’ Budget to Focus on Poverty and Mental Health|World news|The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/14/new-zealands-world-first-wellbeing-budget-to-focus-on-poverty-and-mental-health (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- Sabeti, H. The For-Benefit Enterprise. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- What Are For-Benefit Organizations? Available online: https://www.fourthsector.org/for-benefit-enterprise (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Wilburn, K.; Wilburn, R. The double bottom line: Profit and social benefit. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Enhancing the contributions of SMEs in a global and digitalised economy. Meet. OECD Counc. Minist. Lev. 2017, 1, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017; ISBN 9789284419340. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism & Sustainable Development Goals—Tourism for SDGs. Available online: http://tourism4sdgs.org/tourism-for-sdgs/tourism-and-sdgs/ (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- UNWTO Report Links Sustainable Tourism to 17 SDGs|News|SDG Knowledge Hub|IISD. Available online: http://sdg.iisd.org/news/unwto-report-links-sustainable-tourism-to-17-sdgs/ (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Agyeiwaah, E. Exploring the relevance of sustainability to micro tourism and hospitality accommodation enterprises (MTHAEs): Evidence from home-stay owners. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.; Font, X. Doing good to do well? Corporate social responsibility reasons, practices and impacts in small and medium accommodation enterprises. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depken, D.; Zeman, C. Small business challenges and the triple bottom line, TBL: Needs assessment in a Midwest State, U.S.A. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 135, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.B.; Looijen, A.; Blok, V. Critical success factors for the transition to business models for sustainability in the food and beverage industry in the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019—Reports—World Economic Forum. Available online: https://reports.weforum.org/travel-and-tourism-competitiveness-report-2019/rankings/ (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- El Turismo es el Sector que más Riqueza Aporta a la Economía Española|Economía. Available online: https://www.hosteltur.com/130893_el-turismo-el-sector-que-mas-riqueza-aporta-a-la-economia-espanola.html (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Red Española del Pacto Mundial & Consejo General de Economistas De Eespaña. Guía para PYMES ante los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible; Pacto Mundial Red Española: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koirala, S. SMEs: Key Drivers of Green and Inclusive Growth. OECD Green Growth Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Moraleda, L.; Lafuente-Ibáñez, C.; Muñoz-Mazón, A.; Villacé-Molinero, T. Willingness to Pay More to Stay at a Boutique Hotel with an Environmental Management System. A Preliminary Study in Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlights, 2019th ed.; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de España. Plan de acción para la implementación de la Agenda 2030. Hacia una Estrategia Española de Desarrollo Sostenible. 2019; pp. 1–164. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/20119Spain_Annex_1___PLAN_DE_ACCION_AGENDA_2030_002.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- The Fourth Sector in Ibero-America—Fostering Social & Sustainable Economy. Available online: https://www.elcuartosector.net/en/ (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- Secretaría General Iberoamericana (SEGIB). Business with Purpose and the Rise of the Fourth Sector in Ibero-America; SEGIB: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fourth Sector Network. The Emerging Fourth Sector About Fourth Sector Network; Fourth Sector Network: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. The Fourth Sector: Can Business Unusual Deliver on the SDGs? UNDP. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2018/the-fourth-sector--can-business-unusual-deliver-on-the-sdgs.html (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Carlos, A.; Gutiérrez, M. Social economy and the fourth sector, base and protagonist of social innovation. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2011, 33–60. [Google Scholar]

- The Fourth Sector. Available online: https://www.fourthsector.org/supportive-ecosystem (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Good, W.D.; Advantage, C.; Industry, T. Balancing Purpose and Profit. Why Doing Good Is a Competitive Advantage in the Travel Industry; Skift and Intrepid Group: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zsolnai, L. Spirituality, ethics and sustainability. In The Spiritual Dimension of Business Ethics and Sustainability Management; Springer: New York, UY, USA, 2015; pp. 3–11. ISBN 9783319116778. [Google Scholar]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Kantamara, P. Business ethics and spirituality for corporate sustainability: A Buddhism perspective. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2019, 16, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hategan, V. Philosophical practice and ethics applied in organizations. Ann. Univ. Buchar. 2019, 68, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hategan, V. Interdisciplinary Connections of Philosophical Practice with the Business Environment. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2019, XIX, 504–508. [Google Scholar]

- Hategan, C.-D.; Sirghi, N.; Curea-Pitorac, R.-I.; Hategan, V.-P. Doing Well or Doing Good: The Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Profit in Romanian Companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloch, T.R. Practical Wisdom in Management: Business across Spiritual Traditions; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781351286329. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, S.-Y. From individual intelligence to ecological intelligence-recursive process in eco-philosophy. Universitas (Stuttg) 2012, 39, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Agung, A.A.G.; Suprina, R.; Pusparini, M. The Paradigm of Cosmovision—Based Conservation. TRJ Tour. Res. J. 2019, 3, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsolnai, L.; J. Ims, K.J. Shallow Success and Deep Failure. In Business within Limits: Deep Ecology and Buddhist Economics; Peter Lang.: Oxford, UK, 2006; p. 21. ISBN1 3039107038. ISBN2 9783039107032. [Google Scholar]

- Bouckaert, L.; Zsolnai, L. Spirituality and business: An interdisciplinary overview. Soc. Econ. 2012, 34, 489–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapouraghdam, H.; Alipour, H.; Arasli, H. Workplace spirituality and organization sustainability: A theoretical perspective on hospitality employees’ sustainable behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1583–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, W.E.; Stead, J.G. Green Man Rising: Spirituality and Sustainable Strategic Management; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781461452331. [Google Scholar]

- Bouckaert, L.; Zsolnai, L. Handbook of Spirituality and Business; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 9780230321458. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuuren, B.; Subramanian, S.M.; Hiemstra, W. Community Wellbeing in Biocultural Landscapes—Are We Living Well? Verschuuren, B., Ed.; Practical Action Publishing Ltd.: Rugby, UK, 2014; Volume 1, ISBN 978-1-78044-838-1. [Google Scholar]

- Durán López, M. Sumak Kawsay o Buen Vivir, desde la cosmovisión andina hacia la ética de la sustentabilidad. Pensam. Actual 2010, 10, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Pérezts, M.; Russon, J.A.; Painter, M. This Time from Africa: Developing a Relational Approach to Values-Driven Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 161, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez López, F. A Contribution from the African Cultural Philosophy towards a Harmonious Coexistence in Pluralistic Societies. Pensamiento. Rev. Investig. Inf. Filosófica 2020, 76, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope Francesco, I. Encyclical “Laudato Si”: On Care for our Common Home; Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, A.; Santos, N.J.C.; Kennedy, A. The Papal Encyclical Laudato Si’: A Focus on Sustainability Attentive to the Poor. Papal Encyclical 2017, 5, 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira, C. Laudato Si’: Caring beyond limits with a cosmocentric world vision. Theology 2019, 122, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S.; Marques, J. Spirituality and Sustainability. New Horizons and Examplary Approaches; Dhiman, S., Marques, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 9783319342337. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, A. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; ISBN 9780521344067. [Google Scholar]

- van Meurs, B. Deep Ecology and Nature: Naess, Spinoza, Schelling. Trumpeter 2020, 35, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, S. Two versions of ecosophy: Arne Naess, Félix Guattari, and their connection with semiotics. Sign Syst. Stud. 2016, 44, 511–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drengson, A. Education for Local and Global Ecological Responsibility: Arne Naess’s Cross-Cultural, Ecophilosophy Approach. Available online: http://trumpeter.athabascau.ca/index.php/trumpet/article/download/135/160?inline=1 (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Kenter, J.O.; Raymond, C.M.; van Riper, C.J.; Azzopardi, E.; Brear, M.R.; Calcagni, F.; Christie, I.; Christie, M.; Fordham, A.; Gould, R.K.; et al. Loving the mess: Navigating diversity and conflict in social values for sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1439–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix Guattari. Les Trois Écologies; Galilée: Paris, France, 1989; ISBN 978-84-87101-29-8. (Spanish edition, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Rawluk, A.; Ford, R.; Anderson, N.; Williams, K. Exploring multiple dimensions of values and valuing: A conceptual framework for mapping and translating values for social-ecological research and practice. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argadoña, A. Fostering Values in Organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmeyer, E.A.; Mendiola, R.; Snabe, J.H. Purpose-Driven Business for Sustainable Performance and Progress; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 9780198825067. [Google Scholar]

- Varley, P.; Medway, D. Ecosophy and tourism: Rethinking a mountain resort. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Enter the Triple Bottom Line (Chapter 1). In The Triple Bottom LIne. Does It All Add Up? Assessing the Sustainability of Business and CSR; Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 24–51. ISBN 9781844070152. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, E.; Landua, G. Empresa Regenerativa: Optimizarse para la Abundancia Multicapital; Babelcube Inc.: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2017; ISBN 1-5071-7384-9. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel Christian Wahl Can Regenerative Economics and Mainstream Business Mix? Available online: https://medium.com/activate-the-future/can-regenerative-economics-mainstream-business-mix-ef2f8aafa8d4 (accessed on 25 November 2019).

- The Field Guide to a Regenerative Economy. Available online: http://fieldguide.capitalinstitute.org/ (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Capital Institute—Co-Creating the Regenerative Economy. Understand. Inspire. Engage. Available online: https://capitalinstitute.org/ (accessed on 6 June 2019).

- Wahl, D.C. Designing Regenerative Cultures. Available online: https://medium.com/insurge-intelligence/join-the-re-generation-designing-regenerative-cultures-77f7868c63cd (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Wahl, D.C. Designing Regenerative Cultures; Triarchy Press with International Futures Forum: Axminster, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-909470-78-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra, N. Entrepreneurship Inspired by Nature; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 9783319116778. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra, N. Eco-spirituality and regenerative entrepreneurship. In Ethical Leadership: Indian and European Spiritual Approaches; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 261–273. ISBN 9781137601940. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L. Incorporating values into sustainability decision-making. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 105, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Kläy, A.; Zimmermann, A.B.; Buser, T.; Ingalls, M.; Messerli, P. How can science support the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development? Four tasks to tackle the normative dimension of sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1593–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horcea-Milcu, A.I.; Abson, D.J.; Apetrei, C.I.; Duse, I.A.; Freeth, R.; Riechers, M.; Lam, D.P.M.; Dorninger, C.; Lang, D.J. Values in transformational sustainability science: Four perspectives for change. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- My Way World. My Way Meaningful Hotels. Available online: https://mywayresorts.com/en/my-way-world/ (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Morioka, S.N.; Bolis, I.; Evans, S.; Carvalho, M.M. Transforming sustainability challenges into competitive advantage: Multiple case studies kaleidoscope converging into sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 167, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotherton, B. Researching Hospitality and Tourism; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781446287545. [Google Scholar]

- O.Nyumba, T.; Wilson, K.; Derrick, C.J.; Mukherjee, N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 175. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch Rabell, M.; Bastons, M. Spirituality as reinforcement of people-focused work: A philosophical foundation. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, H.; Ishaq, M.I.; Amin, A.; Ahmed, R. Ethical leadership, work engagement, employees’ well-being, and performance: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 2008–2026. [Google Scholar]

- Iriarte, L.; Musikanski, L. Bridging the Gap between the Sustainable Development Goals and Happiness Metrics. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2019, 1, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Ertuna, B.; Salman, D. Small-sized tourism projects in rural areas: The compounding effects on societal wellbeing. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. Joining Forces—Collaborative Processes for Sustainable and Competitive Tourism; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, R. Wellbeing and Self-Transformation in Natural Landscapes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 9783319976730. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Gámez, M.Á.; Gutiérrez-Ruiz, A.M.; Becerra-Vicario, R.; Ruiz-Palomo, D. The effects of creating shared value on the hotel performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1784. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, T.-Y.; Chuang, C.-M. Creating Shared Value Through Implementing Green Practices for Star Hotels. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 678–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakulevski, L.; Boshkov, T. Circular Economy: Potential and Challenges. Int. J. Inf. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Compliance Assistance Programme for SMEs—Environment—European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/sme/index_en.htm (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Circular Economy. Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/industry/sustainability/circular-economy_en (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- MINECO; MAPAMA. España Circular 2030. Estrategia Española de Economía Circular; Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente. Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad: Madrid, Spain, 2018.

- Greenpeace. Maldito Plástico. Reciclar no es Suficiente; Greenpeace: Madrid, Spain, 2019; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, C.M.; Kenter, J.O.; van Riper, C.J.; Rawluk, A.; Kendal, D. Editorial overview: Theoretical traditions in social values for sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, I.J.; Raymond, C.M. Positive psychology perspectives on social values and their application to intentionally delivered sustainability interventions. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatić, A.; Zagorac, I. The Methodology of Philosophical Practice: Eclecticism and/or Integrativeness? Philosophia 2016, 44, 1419–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.S.; Vergragt, P.J. From consumerism to wellbeing: Toward a cultural transition? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradoja del Turismo Español: Regiones Cada vez Más Ricas Con Habitantes Más Pobres. Available online: https://www.elconfidencial.com/economia/2018-10-04/turismo-espana-regiones-ricas-habitantes-pobres_1625210/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- How a Small Chain Aims to Deliver Wellbeing in the Time of Covid-19|Travel Industry News & Conferences—EyeforTravel. Available online: https://www.eyefortravel.com/distribution-strategies/how-small-chain-aims-deliver-wellbeing-time-covid-19 (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Gill, P.; Stewart, K.; Treasure, E.; Chadwick, B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia-Pérez, M.; Figueroa-Domecq, C.; Fuentes-Moraleda, L.; Muñoz-Mazón, A. Incorporating a gender approach in the hospitality industry: Female executives’ perceptions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Medel, M.Á. El hilo de Ariadna: La mujer y lo femenino en la salida del laberinto. In Proceedings of the I Congreso Universitario Andaluz Investigación y Género, Sevilla, Spain, 17–18 June 2009; pp. 1413–1422. [Google Scholar]

- Sin Ariadna no Saldremos del Presente Laberinto. Available online: https://theconversation.com/sin-ariadna-no-saldremos-del-presente-laberinto-143853 (accessed on 19 August 2020).

| Participants | Position | Shareholder | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | CEO, member of Board of Directors | ☑ | PD, SSMMI |

| #2 | COO, member of Board of Directors | ☑ | PD, SSMMI |

| #3 | CFO, member of Board of Directors | ☑ | PD, SSMMI |

| #4 | HRO, member of Management Committee | -- | SSMMI |

| # | FG Themes | Reflections to Identify Sustainability Values | SDGs Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mental Ecology | Which values for sustainability does the Purpose bring to the SSMM to enhance people’s wellbeing? | People |

| 2 | Social Ecology | Which values for sustainability does the Purpose bring to the SSMM to contribute to the community’s wellbeing? | Prosperity Peace Partnership |

| 3 | Environmental Ecology | Which values for sustainability does the Purpose bring to the SSMM to help make the planet better? | Planet |

| Themes | SDGs Area | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|

| Mental ecology | People |

|

| Social ecology | Prosperity Peace Partnership |

|

| Environmental ecology | Planet |

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rubio-Mozos, E.; García-Muiña, F.E.; Fuentes-Moraleda, L. Application of Ecosophical Perspective to Advance to the SDGs: Theoretical Approach on Values for Sustainability in a 4S Hotel Company. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187713

Rubio-Mozos E, García-Muiña FE, Fuentes-Moraleda L. Application of Ecosophical Perspective to Advance to the SDGs: Theoretical Approach on Values for Sustainability in a 4S Hotel Company. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187713

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubio-Mozos, Ernestina, Fernando E. García-Muiña, and Laura Fuentes-Moraleda. 2020. "Application of Ecosophical Perspective to Advance to the SDGs: Theoretical Approach on Values for Sustainability in a 4S Hotel Company" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187713

APA StyleRubio-Mozos, E., García-Muiña, F. E., & Fuentes-Moraleda, L. (2020). Application of Ecosophical Perspective to Advance to the SDGs: Theoretical Approach on Values for Sustainability in a 4S Hotel Company. Sustainability, 12(18), 7713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187713