From Center to Periphery and Back Again: A Systematic Literature Review of Refugee Entrepreneurship

Abstract

1. Introduction

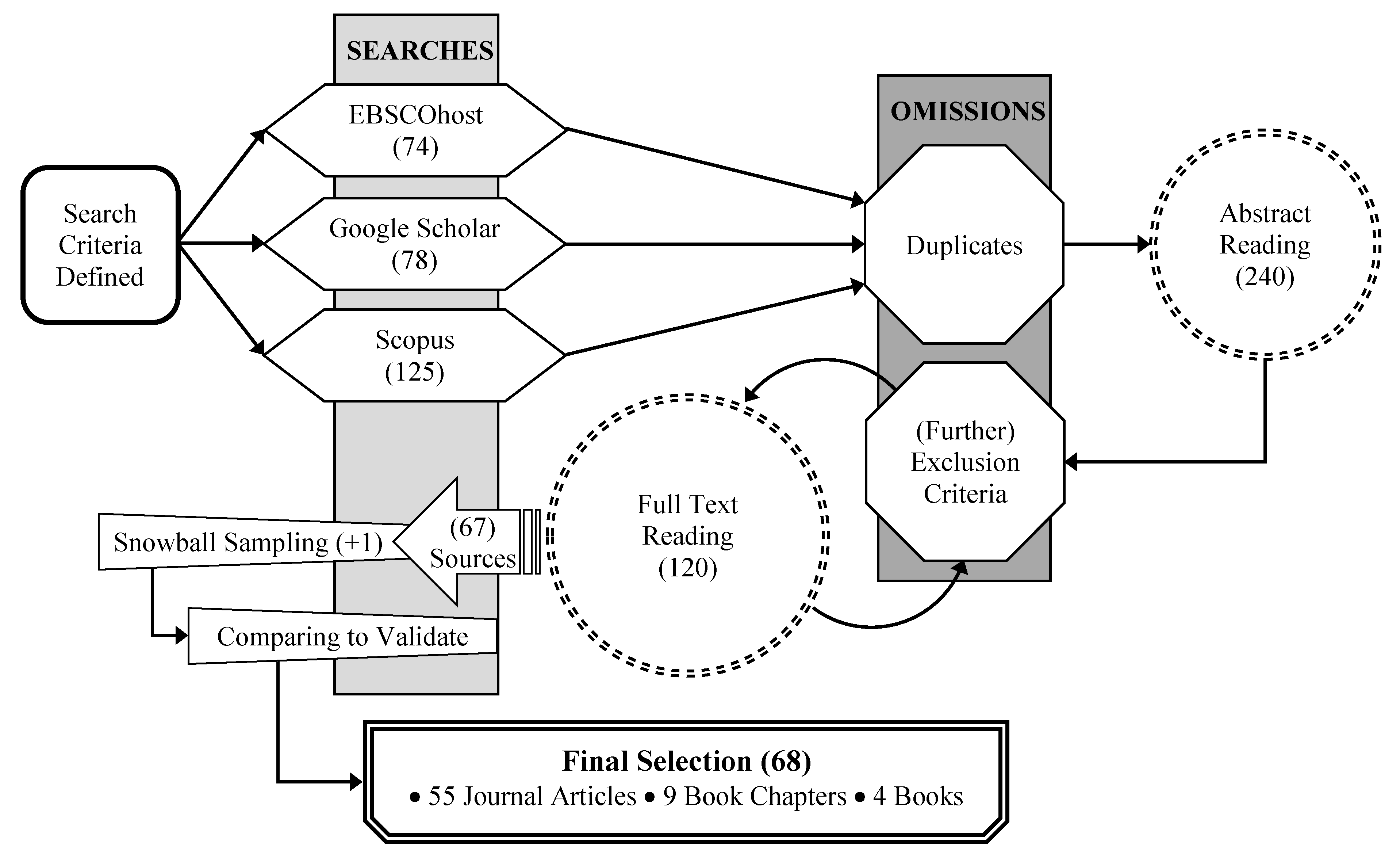

2. Systematic Literature Review Method

2.1. Sampling and Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis Method

3. Outcomes and Analysis

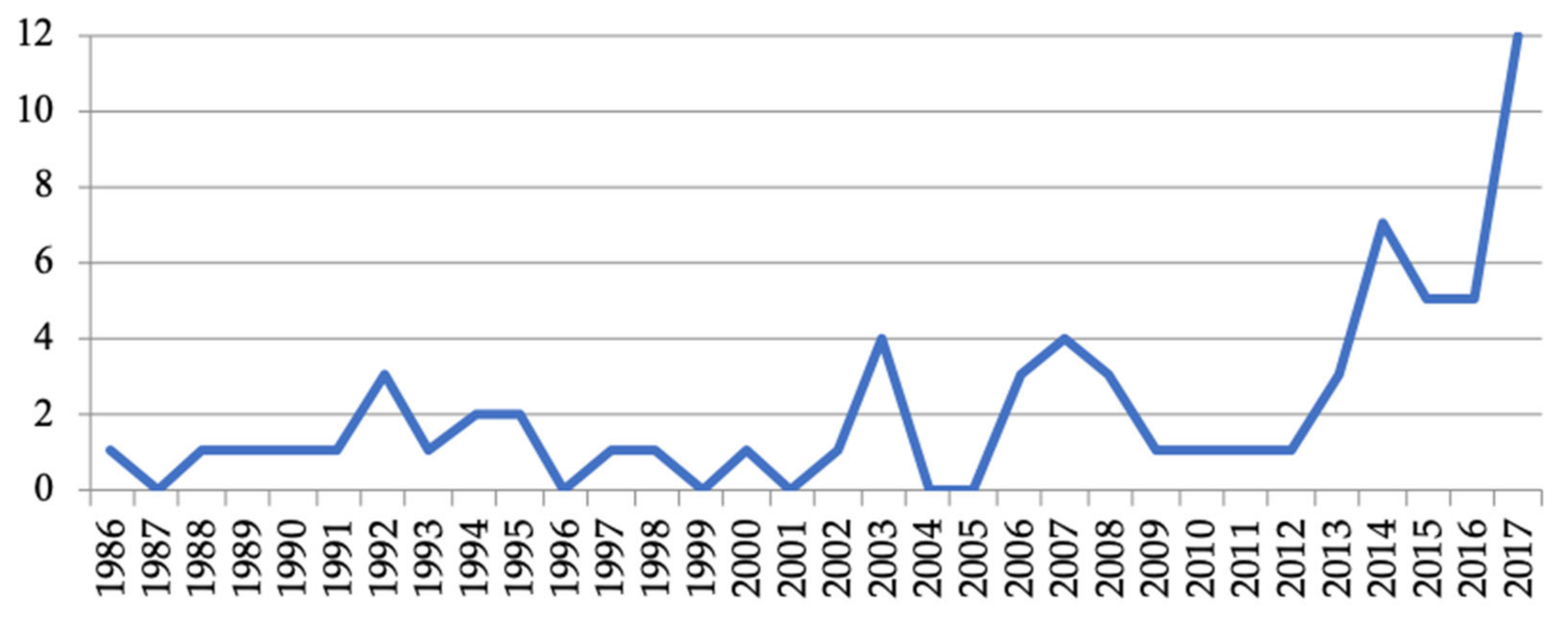

3.1. Development of the Field of Refugee Entrepreneurship Research

3.1.1. Centrality Versus Peripherality of Publications

3.2. Content Analysis

3.2.1. Geographies and Timeframes

3.2.2. Objectives and Scopes of the Analyzed Studies

3.2.3. Theoretical Framing

3.2.4. Applied Methodology

3.3. Thematic Clusters in Refugee Entrepreneurship

3.3.1. Difference between Migrant and Refugee Entrepreneurship

- Less extensive social networks;

- Limited access to COO resources, if any at all;

- Psychological instability due to flight and trauma;

- Little or no preparation in migration processes;

- Needing to leave valuable assets and resources in their COO;

- Many remain unsuited for paid labor in the COR (would not have left).

3.3.2. Factors Influencing Refugee Entrepreneurship

3.3.3. Impact of Refugee Entrepreneurship

4. Concluding Insights and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Additional Tables

| Year of Publication | Author(s) |

|---|---|

| 1986 | Fass |

| 1988 | Gold |

| 1989 | Basok |

| 1990 | Moore |

| 1991 | Gold |

| 1992 | Gold*; Gold; LaTowsky and Grierson |

| 1993 | Basok * |

| 1994 | Gold **; Singh |

| 1995 | Halter **; Smith-Hefner ** |

| 1997 | Kaplan |

| 1998 | Miyares |

| 2000 | Johnson |

| 2002 | Hiebert |

| 2003 | Kibreab; Mamgain and Collins; Ong *; Serdedakis, Tsiolis, Tzanakis and Papaioannou |

| 2006 | Fuller-Love, Lim and Akehurst; Garnham; Wauters and Lambrecht |

| 2007 | Campbell **; Fong et al.; Lyon, Sepulveda and Syrett; Wauters and Lambrecht ** |

| 2008 | Sheridan **; Tömöry; Wauters and Lambrecht |

| 2009 | Halkias et al. |

| 2010 | Abt ** |

| 2011 | Ayadurai |

| 2012 | Dana |

| 2013 | Gonzales, Forrest and Balos; Hugo; Sabar and Posner |

| 2014 | Călin-Ştefan; Gold; Morais; Omeje and Mwangi; Pulla and Kharel; Ranalli; Şaul |

| 2015 | Beehner; De Jager; Ilcan and Rygiel; Northcote and Dodson **; Raijman and Barak-Bianco |

| 2016 | Abdel Jabbar and Ibrahim Zaza; Elo and Vemuri; Kachkar, Mohammed, Saad and Kayadibi; Sánchez Piñeiro and Saavedra; van Kooy |

| 2017 | Betts, Omata and Bloom; Bizri; Bujaki, Gaudet and Iuliano; Crush and McCordic; Crush, Tawodzera, McCordic and Ramachandran; David and Coenen **; Gürsel; Kachkar; Lankov, Ward, Yoo and Kim; Omata; Scott and Getahun *; Suter |

| 2018 | Sandberg, Immonen and Kok 1 |

| Journal | Author(s) | Year | Field of Journal | Country | Impact Factor (Thomson Reuters) * | H Index ** | SJR (2017) *** | CiteScore (2018) | SNIP (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal | Suter | 2017 | Arts and Humanities; Social Sciences (Anthropology, Cultural Studies, Demography, Sociology, and Political Science) | UK | 0.300 | 7 | Q3 0.112 | 0.36 | 0.702 |

| African Geographical Review | Omata | 2017 | Earth and Planetary Sciences (Earth-Surface Processes); Social Sciences (Geography, Planning and Development) | UK | 1.242 | 10 | Q2 0.432 | 1.44 | 0.753 |

| African Human Mobility Review | Crush and McCordic | 2017 | Socio-Economic, Political, Legislative and Development of Human Mobility in Africa; Migrant Relations | South Africa | Not listed | ||||

| Crush, Tawodzera, McCordic and Ramachandran | 2017 | ||||||||

| Asian Journal of Business and Management Sciences | Ayadurai | 2011 | Management, Organizational Behavior, Entrepreneurship, Economics, Accounting and Finance, Production and Operations Management, Human Resources Management, Strategic Management, Marketing | Malaysia | Not listed | ||||

| Critical Perspectives on Accounting | Bujaki, Gaudet and Iuliano | 2017 | Business, Management and Accounting; Decision Sciences (Information Systems and Management); Economics, Econometrics and Finance; Social Sciences (Sociology And Political Science) | USA | 4.010 | 57 | Q1 1.773 | 4.21 | 1.961 |

| Diaspora Studies | Elo and Vemuri | 2016 | Social Sciences (Demography, Geography, Planning and Development, Political Sciences and International Relations) | UK | 0.565 | 3 | Q3 0.211 | 0.74 | 1.135 |

| Economic Geography | Kaplan | 1997 | Economics, Econometrics and Finance (Economics and Econometrics); Social Sciences (Geography, Planning and Development) | UK | 5.091 | 74 | Q1 2.501 | 5.31 | 2.366 |

| Economic Sociology | Raijman and Barak-Bianco | 2015 | Economics, Social Sciences | Germany | Not listed | ||||

| Entrepreneurship and Regional Development | Bizri | 2017 | Business, Management and Accounting (Business and International Management); Economics, Econometrics and Finance | UK | 3.081 | 75 | Q1 1.461 | 3.62 | 1.352 |

| Ethnic and Racial Studies | Gold | 1988 | Sociology and Political Sciences, Anthropology, Cultural Studies, Sociology, and Political Sciences | UK | 1.387 | 79 | Q1 0.977 | 1.67 | 1.263 |

| Food, Culture, and Society | Sabar and Posner | 2013 | Agricultural and Biological Sciences (Food Science); Psychology (Social Psychology); Social Sciences (Cultural Studies) | UK | 0.833 | 17 | Q3 0.334 | 1.1 | 0.867 |

| Forced Migration Review | Sánchez Piñeiro and Saavedra | 2016 | Social Sciences | UK | Not listed | ||||

| van Kooy | 2016 | ||||||||

| Hungarian Studies Review | Tömöry | 2008 | Hungarian Studies | Canada | Not listed | ||||

| Immigrants and Minorities | Moore | 1990 | Social Sciences; Demography | UK | 0.231 | 15 | Q4 0.104 | 0.4 | 0.515 |

| International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal | Fuller-Love, Lim and Akehurst | 2006 | Business, Management and Accounting (Management of Information Systems; Management of Technology and Innovation) | Germany | 2.938 | 41 | Q2 0.746 | 4.01 | 1.814 |

| Wauters and Lambrecht | 2006 | ||||||||

| International Journal of Adolescence and Youth | Abdel Jabbar and Ibrahim Zaza | 2016 | Social Sciences; Health | UK | 0.792 | 12 | Q3 0.295 | 1.53 | 0.905 |

| International Journal of Business Innovation and Research | Halkias et al. | 2009 | Business, Management and Accounting, Business and International Management, Management of Technology and Innovation | UK | 0.731 | 18 | Q3 0.280 | 0.64 | 0.394 |

| International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business | Dana | 2012 | Business, Management and Accounting (Business and International Management); Economics, Econometrics and Finance | UK | 1.131 | 26 | Q3 0.401 | 1.14 | 0.665 |

| Sandberg, Immonen and Kok | 2018 | ||||||||

| International Migration | Hugo | 2013 | Social Sciences (Demography) | UK | 1.304 | 56 | Q2 0.887 | 1.25 | 0.903 |

| International Migration Review | Fass | 1986 | Arts and Humanities; Social Sciences (Demography) | USA | 1.826 | 86 | Q1 1.641 | 2.09 | 1.365 |

| Kibreab | 2003 | ||||||||

| International Political Sociology | Ilcan and Rygiel | 2015 | Social Sciences, Sociology, and Political Sciences | UK | 2.275 | 34 | Q1 1.465 | 2.47 | 1.583 |

| International Review of Sociology | Serdedakis, Tsiolis, Tzanakis and Papaioannou | 2003 | Social Sciences (Sociology and Political Sciences) | UK | 0.683 | 20 | Q3 0.206 | 0.97 | 0.59 |

| ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance | Kachkar | 2017 | Economics, Econometrics and Finance; Social Sciences (Development) | UK | N/A; only 2017< | 2 | Q4 No data | 0.27 | 0.441 |

| Journal of Asian and African Social Science and Humanities | Kachkar, Mohammed, Saad and Kayadibi | 2016 | Humanities and the Social Sciences | Canada Philippines Republic of Maldives Australia Bangladesh | Not listed | ||||

| Journal of Community Positive Practices | Gonzales, Forrest and Balos | 2013 | Social Research in the Social Sciences | Romania | Not listed | ||||

| Journal of Contemporary Ethnography | Gold | 2014 | Arts and Humanities (Language and Linguistics); Social Sciences (Anthropology Sociology and Political Science); Urban Studies | USA | 1.037 | 46 | Q1 0.580 | 1.52 | 1.007 |

| Journal of East Asian Studies | Lankov, Ward, Yoo and Kim | 2017 | Economics, Econometrics and Finance; Economics and Econometrics; Social Sciences (Development, Political Science and International Relations, Sociology and Political Science) | UK | 1.188 | 20 | Q2 0.590 | 1.1 | 1.133 |

| Journal of Entrepreneurship | Singh | 1994 | Business, Management and Accounting (Business and International Management; Strategy and Management); Economics, Econometrics and Finance | USA | 0.818 | 11 | Q3 0.405 | 1.31 | 0.828 |

| Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work | Fong et al. | 2007 | Social Sciences (Education, Health, Social Work) | USA | 0.211 | 23 | Q4 0.163 | 1.16 | 0.717 |

| Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies | Wauters and Lambrecht | 2008 | Arts and Humanities; Social Sciences (Demography) | UK | 2.201 | 75 | Q1 1.486 | 2.91 | 1.852 |

| Journal of International Affairs | Beehner | 2015 | International Relations | USA | Not listed | ||||

| Journal on Migration and Human Security | Betts, Omata and Bloom | 2017 | Political Science, Colonies and Colonization, Emigration and Immigration, International Migration | USA | Not listed | ||||

| Journal of Refugee Studies | Mamgain and Collins | 2003 | Social Sciences (Geography, Planning and Development; Political Sciences and International Relations) | UK | 1.549 | 45 | Q1 1.197 | 2.11 | 1.945 |

| Ranalli | 2014 | ||||||||

| Journal of Small Business Management | Johnson | 2000 | Social Sciences (Geography, Planning and Development; Political Sciences and International Relations); Business, Management and Accounting (Management of Technology and Innovation; Strategy and Management) | UK | 3.712 | 94 | Q1 1.337 | 5.29 | 2.109 |

| Journal of Third World Studies | Omeje and Mwangi | 2014 | Social Sciences (Development; Geography, Planning and Development, Political Science and International Relations) | USA | 0.000 | 10 | Q4 0.114 | - | 0.025 |

| Labour, Capital and Society | Basok | 1989 | Social Sciences (Demography; Geography, Planning and Development) | Canada | 0.300 | 10 | Q4 0.109 | - | 0.0 |

| Labour, Employment and Work in New Zealand | Garnham | 2006 | Labor Relations | New Zealand | Not listed | ||||

| Local Economy | Lyon, Sepulveda and Syrett | 2007 | Economics; Econometrics; Finance | USA | 1.211 | 32 | Q2 0.407 | 1.25 | 0.772 |

| Movements, Journal for Critical Migration and Border Regime Studies | Gürsel | 2017 | Migration | Germany | Not listed | ||||

| Review of Policy Research | Gold | 1992b | Environment Science (Management, Monitoring, Policy and Law); Social Sciences (Geography Planning and Development, Public Administration) | UK | 1.359 | 40 | Q2 0.637 | 2.07 | 0.838 |

| Romanian Journal of Political Sciences | Călin-Ştefan | 2014 | Social Sciences | Romania | Not listed | ||||

| Small Enterprise Development | LaTowsky and Grierson | 1992 | (Currently under the name Enterprise Development and Microfinance, An International Journal) Business, Banking, Markets, Finance | UK | Not listed | ||||

| South African Journal on Human Rights | De Jager | 2015 | Social Sciences (Law, Sociology and Political Sciences) | UK | 0.200 | 11 | Q4 0.117 | 0.27 | 0.356 |

| Space and Culture, India | Pulla and Kharel | 2014 | Arts and Humanities; Business, Management and Accounting (Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management); Social Sciences (Cultural Studies; Geography, Planning and Development; Urban Studies) | UK | 0.463 | 6 | Q2 0.308 | 0.28 | 0.408 |

| Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie | Hiebert | 2002 | Economics, Econometrics and Finance; Economics and Econometrics; Social Sciences (Geography, Planning and Development) | UK | 0.952 | 48 | Q2 0.649 | 1.22 | 0.69 |

| Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development | Morais | 2014 | Social Sciences (Anthropology; Geography, Planning and Development; Urban Studies) | USA | - | 16 | Not listed; Coverage was <2015 | ||

| Şaul | 2014 | ||||||||

| Urban Geography | Miyares | 1998 | Social Sciences (Geography, Planning and Development; Urban Studies) | UK | 2.605 | 58 | Q1 1.183 | 2.99 | 1.585 |

| Visual Sociology Studies | Gold | 1991 | Empirical Visual Research | UK | Not listed | ||||

References

- Arendt, H. We refugees. Menorah J. 1943, 1, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Castles, S. Twenty-first-century migration as a challenge to sociology. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2007, 33, 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Joppke, C. How immigration is changing citizenship: A comparative view. Ethn. Racial Stud. 1999, 22, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zolberg, A.R.; Woon, L.L. Why Islam is like Spanish: Cultural incorporation in Europe and the United States. Politics Soc. 1999, 27, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Figures at a Glance; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Refugee Statistics; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Is This Humanitarian Migration Crisis Different? Migration Policy Debates; No 7. Report; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- George, M. A theoretical understanding of refugee trauma. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2010, 38, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, A. Refugees in the UK labour market: The conflict between economic integration and policy-led labour market restriction. J. Soc. Policy 2008, 37, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, A. Living in fear: Rejected asylum seekers living as irregular migrants in England. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2014, 40, 1507–1525. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, F.; Sepulveda, L.; Syrett, S. Enterprising refugees: Contributions and challenges in deprived urban areas. Local Econ. 2007, 22, 362–375. [Google Scholar]

- Phillimore, J.; Goodson, L. Problem or opportunity? Asylum seekers, refugees, employment and social exclusion in deprived urban areas. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 1715–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Ager, A.; Strang, A. Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. J. Refug. Stud. 2008, 21, 166–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bordignon, M.; Moriconi, S. The Case for a Common European Refugee Policy; No. 2017/8; Bruegel Policy Contribution: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kancs, D.A.; Lecca, P. Long-term social, economic and fiscal effects of immigration into the EU: The role of the integration policy. World Econ. 2018, 41, 2599–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, N.K. The employment experiences of Canadian refugees: Measuring the impact of human and social capital on quality of employment. Can. Rev. Sociol. Rev. Can. Sociol. 2008, 40, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi Cheung, S.; Phillimore, J. Refugees, social capital, and labour market integration in the UK. Sociology 2014, 48, 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, T.A.; Prasad, A. Entrepreneurship amid concurrent institutional constraints in less developed countries. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 934–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, S.; Ram, M.; Theodorakopoulos, N.; Jones, T. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2007, 30, 1024–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, M.; Theodorakopoulos, N.; Jones, T. Forms of capital, mixed embeddedness and Somali enterprise. Work Employ. Soc. 2008, 22, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Ram, M.; Edwards, P.; Kiselinchev, A.; Muchenje, L. Mixed embeddedness and new migrant enterprise in the UK. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2014, 26, 500–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Zurich & Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. Refugee Movements; University of Zurich & Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation: Berne, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.; Zhu, J. Neo-colonialismin the academy? Anglo-American domination in management journals. Organization 2012, 19, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, B.; Lambrecht, J. Barriers to refugee entrepreneurship in Belgium: Towards an explanatory model. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2008, 34, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizri, R.M. Refugee-entrepreneurship: A social capital perspective. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, T.V.; Brenner, G.; Filion, L.J. Social capital, networks and ethnic minority entrepreneurs: Transnational entrepreneurship and bootstrap capitalism. In Globalization and Entrepreneurship: Policy and Strategy Perspectives; Etemad, E., Wright, R.W., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Piperopoulos, P. Ethnic minority businesses and immigrant entrepreneurship in Greece. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2010, 17, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucassen, L. Peeling an onion: The “refugee crisis” from a historical perspective. Ethnic Racial Stud. 2017, 41, 383–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parater, L. 10 Infographics that Show the Insane Scale of Global Displacement; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo, G. The economic contribution of humanitarian settlers in Australia. Int. Migr. 2013, 52, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.J. Refugees and small business: The case of Soviet Jews and Vietnamese. Ethn. Racial Stud. 1988, 11, 411–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.H. The creation of an ethnic economy: Indochinese business expansion in Saint Paul. Econ. Geogr. 1997, 73, 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnham, A. Refugees and the entrepreneurial process. In Labour Employment and Work in New Zealand; Victoria University of Wellington: Wellington, New Zealand, 2006; pp. 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrunn, S.; Iannone, R.L. Neoliberalist undercurrents in entrepreneurship policy. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 5, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduyn, K.; Dey, P.; Tedmanson, D. A critical understanding of entrepreneurship. Rev. De L’Entrepreneuriat 2017, 16, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.; von Bloh, J.; Brixy, U. Unternehmensgründung im weltweiten vergleich. In Global Entrepreneurship Monitor; Länderbericht Deutschland 2015; Institut für Arbeitsmarkt-und Berufsforschung: Hannover, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- New American Economy. From Struggle to Resilience: The Economic Impact of Refugees in America; Report; New American Economy: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Refugee Entrepreneurship: A Case-Based Topography; Heilbrunn, S., Freiling, J., Harima, A., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrunn, S.; Iannone, R.L. Introduction. In Refugee Entrepreneurship: A Case Based Topography; Heilbrunn, S., Freiling, J., Harima, A., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2018; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Refai, D.; Haloub, R.; Lever, J. Contextualizing entrepreneurial identity among Syrian refugees in Jordan: The emergence of a destabilized habitus? Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2018, 19, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Breier, M.; Dasí-Rodríguez, S. The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1023–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga-Isla, R.; Rialp, A. Systematic review of immigrant entrepreneurship literature: Previous findings and ways forward. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 819–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, R.; Kovalainen, A. Researching small firms and entrepreneurship: Past, present and future. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2009, 11, 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneel, J.; de Cock, R. Entry mode research and SMEs: A review and future research agenda. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54 (Suppl. 1), 135–167. [Google Scholar]

- Dheer, R.J.S. Entrepreneurship by immigrants: A review of existing literature and directions for future research. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 555–614. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Burtscher, J.; Vallaster, C.; Angerer, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship orientation: A reflection on the status-quo research on factors facilitating responsible managerial practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sassmannshausen, S.P.; Volkmann, C. The scientometrics of social entrepreneurship and its establishment as an academic field. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 56, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, A.; Urbano, D.; Dandolini, G.A.; de Souza, J.A.; Guerrero, M. Innovation and entrepreneurship in the academic setting: A systematic literature review. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapkau, F.B.; Schwens, C.; Kabst, R. The role of prior entrepreneurial exposure in the entrepreneurial process: A review and future research implications. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017, 55, 56–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.V.; Coviello, N.; Tang, Y.K. International entrepreneurship research (1989–2009): A domain ontology and thematic analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 632–659. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, P.; Ram, M.; Jones, T.; Doldor, S. New migrant businesses and their workers: Developing, but not transforming, the ethnic economy. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2016, 39, 1587–1617. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, M.; Jones, T.; Villares-Varela, M. Migrant entrepreneurship: Reflections on research and practice. Int. Small Bus. J. 2017, 35, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aubry, M.; Bonnet, J.; Renou-Maissant, P. Entrepreneurship and the business cycle: The “Schumpeter” effect versus the “refugee” effect—A French appraisal based on regional data. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2015, 54, 23–55. [Google Scholar]

- Thurik, A.R.; Carree, M.A.; van Stel, A.; Audretsch, D.B. Does self-employment reduce unemployment? J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 673–686. [Google Scholar]

- Kaunert, C.; Léonard, S. The European union asylum policy after the treaty of Lisbon and the Stockholm programme: Towards supranational governance in a common area of protection? Refug. Surv. Q. 2012, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, M.; Wennberg, K. Why family matters: The impact of family resources on immigrant entrepreneurs’ exit from entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 687–704. [Google Scholar]

- Labrianidis, L.; Hatziprokopiou, P. Migrant entrepreneurship in Greece: Diversity of pathways for emerging ethnic business communities in Thessaloniki. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2010, 11, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.; Cummings, M.E.; Vaaler, P.M. Economic informality and the venture funding impact of migrant remittances to developing countries. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 526–545. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I.; Ventresca, M.J. Building inclusive markets in rural Bangladesh: How intermediaries work institutional voids. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 819–850. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Entrepreneurship in and around institutional voids: A case study from Bangladesh. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 419–435. [Google Scholar]

- Entrepreneurship Education and Training: Insights from Ghana, Kenya, and Mozambique; Robb, A., Valerio, A., Parton, B., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, S.; Immonen, R.; Kok, S. Refugee entrepreneurship: Taking a social network view on immigrants with refugee backgrounds starting transnational businesses in Sweden. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2018, 36, 216–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, D.T. Unconventional uses of on-line information retrieval systems: On-line bibliometric studies. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1977, 28, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estabrooks, C.A.; Winther, C.; Derksen, L. Mapping the field: A bibliometric analysis of the research utilization literature in nursing. Nurs. Res. 2004, 53, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, S.J. Ethnic boundaries and ethnic entrepreneurship: A photo-elicitation study. Vis. Stud. 1991, 6, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.J. Refugee Communities: A Comparative Field Study; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, S.J. The employment potential for refugee entrepreneurship Soviet Jews and Vietnamese in California. Rev. Policy Res. 11, 176–186. [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.J. Soviet Jews in the United States. In American Jewish Year Book: A record of Events and Trends in American and World Jewish Life; Singer, D., Seldin, R.R., Eds.; The American Jewish Committee: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 94, pp. 3–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, S.J. Contextual and family determinants of immigrant women’s self-employment: The case of Vietnamese, Russian-speaking Jews, and Israelis. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2014, 43, 228–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, B.; Lambrecht, J. Refugee entrepreneurship in Belgium: Potential and practice. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2006, 2, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, B.; Lambrecht, J. Refugee entrepreneurship. The case of Belgium. In Entrepreneurship, Competitiveness and Local Development: Frontiers in European Entrepreneurship Research; Iandoli, L., Landström, H., Raffa, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; pp. 200–222. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Economic Situation and Prospects 2014: Country Classification; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ayadurai, S. Challenges faced by women refugees in initiating entrepreneurial ventures in a host country: Case study of UNHCR women refugees in Malaysia. Asian J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2011, 1, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, G.; Posner, R. Remembering the past and constructing the future over a communal plate: Restaurants established by African asylum seekers in Tel Aviv. Food Cult. Soc. 2013, 16, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călin-Ştefan, G. The integration of Syrian-Armenians in the Republic of Armenia: A case study. Rom. J. Political Sci. 2014, 14, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, I. African female nascent entrepreneurship in the Macao, S.A.R. Urban Anthropol. Stud. Cult. Syst. World Econ. Dev. 2014, 43, 57–104. [Google Scholar]

- Omeje, K.; Mwangi, J. Business travails in the Diaspora: The challenges and resilience of Somali refugee business community in Nairobi. J. Third World Stud. 2014, 31, 185–218. [Google Scholar]

- Pulla, V.; Kharel, P. The carpets and Karma: The resilient story of the Tibetan community in two settlements in India and Nepal. Space Cult. India 2014, 1, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- De Jager, J. The right of asylum seekers and refugees in South Africa to self-employment: A comment on Somali Association of South Africa V Limpopo Department of Economic Development, Environment and Tourism. South. Afr. J. Hum. Rights 2015, 31, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijman, R.; Barak-Bianco, A. Asylum seeker entrepreneurs in Israel. Econ. Sociol. Eur. Electron. Newsl. 2015, 16, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel Jabbar, S.; Ibrahim Zaza, H. Evaluating a vocational training programme for women refugees at the Zaatari camp in Jordan: Women empowerment—A journey and not an output. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2016, 21, 304–319. [Google Scholar]

- Kachkar, O.; Mohammed, M.O.; Saad, N.; Kayadibi, S. Refugee microenterprises: Prospects and challenges. J. Asian Afr. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2016, 2, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kachkar, O.A. Towards the establishment of cash waqf microfinance fund for refugees. ISRA Int. J. Islamic Financ. 2017, 9, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankov, A.; Ward, P.; Yoo, H.Y.; Kim, J.Y. Making money in the state: North Korea’s pseudo-state enterprises in the early 2000s. J. East Asian Stud. 2017, 17, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Singh, S. Refugees as entrepreneurs: The case of the Indian bicycle industry. J. Entrep. 1994, 3, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SENSE (Research School for Socio-Economic and Natural Sciences of the Environment). The WASS_SENSE Book Publishers Ranking List 2017. Available online: http://www.sense.nl/organisation/documentation (accessed on 20 June 2017).

- EdUHK (Education University of Hong Kong). Ranking List of Academic Book Publishers. Available online: https://www.eduhk.hk/include_n/getrichfile.php?key=95030d9da8144788e3752da05358f071&secid=50424&filename=secstaffcorner/research_doc/Compiled_Publisher_List.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- Basok, T. How useful is the “Petty Commodity Production” approach? Explaining the survival and success of small Salvadorean urban enterprises in Costa Rica. Labour Cap. Soc. 1989, 22, 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. Jewish refugee entrepreneurs and the Dutch economy in the 1930s. Immigr. Minor. 1990, 9, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaTowsky, R.; Grierson, J. Traditional apprenticeships and enterprise support networks. Small Enterp. Dev. 1992, 3, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halter, M. Ethnicity and the entrepreneur: Self-employment among former Soviet Jewish refugees. In New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs; Halter, M., Ed.; University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Hefner, N. The culture of entrepreneurship among Khmer refugees. In New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs; Halter, M., Ed.; University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Serdedakis, N.; Tsiolis, G.; Tzanakis, M.; Papaioannou, S. Strategies of social integration in the biographies of Greek female immigrants coming from the former Soviet Union: Self-employment as an alternative. Int. Rev. Sociol. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2003, 13, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, R.; Busch, N.B.; Armour, M.; Heffron, L.C.; Chanmugam, A. Pathways to self-sufficiency: Successful entrepreneurship for refugees. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work 2007, 16, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, V. Loneliness and satisfaction: Narratives of Vietnamese refugee integration into Irish society. In Facing the Other: Interdisciplinary Studies on Race, Gender and Social Justice in Ireland; Faragó, B., Sullivan, M., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2008; pp. 108–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tömöry, É. Immigrant entrepreneurship: How the ‘56-ers helped to build Canada’s economy. Hung. Stud. Rev. 2008, 35, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Halkias, D.; Nwajiuba, C.; Harkiolakis, N.; Clayton, G.; Dimitris Akrivos, D.; Caracatsanis, S. Characteristics and business profiles of immigrant owned small firms: The case of Albanian immigrant entrepreneurs in Greece. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2009, 3, 382–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.-P. Learning from Lagnado about self-employment and entrepreneurship in Egypt. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2012, 17, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, V.; Forrest, N.; Balos, N. Refugee farmers and the social enterprise model in the American Southwest. J. Community Posit. Pract. 2013, 4, 32–54. [Google Scholar]

- Şaul, M. A different “Kargo”: Sub-Saharan migrants in Istanbul and African Commerce. Urban Anthropol. Stud. Cult. Syst. World Econ. Dev. 2014, 43, 143–203. [Google Scholar]

- Beehner, L. Are Syria’s do-it-yourself refugees outliers or examples of a new norm? J. Int. Aff. 2015, 68, 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Northcote, M.; Dodson, B. Refugees and asylum seekers in Cape Town’s informal economy. In Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa; Crush, J., Chikanda, A., Skinner, C., Eds.; Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), African Centre for Cities and International Development Research Centre: Cape Town, South Africa, 2015; pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, M.; Vemuri, R. Organizing mobility: A case study of Bukharian Jewish diaspora. Diaspora Stud. 2016, 9, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Piñeiro, O.; Saavedra, R. Doing business in Ecuador. Forced Migr. Rev. 2016, 52, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- van Kooy, J. Refugee women as entrepreneurs in Australia. Forced Migr. Rev. 2016, 53, 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, A.; Omata, N.; Bloom, L. Thrive or survive? Explaining variation in economic outcomes for refugees. J. Migr. Hum. Secur. 2017, 5, 716–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crush, J.; Tawodzera, G.; McCordic, C.; Ramachandran, S. Refugee Entrepreneurial Economies in Urban South Africa; Migration Policy Series No. 76; Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP): Cape Town, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crush, J.; McCordic, C. Comparing refugee and South African migrant enterprise in the urban informal sector. In African Human Mobility Review; Special Issue; Scalabrini Institute for Human Mobility in Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2017; pp. 820–853. [Google Scholar]

- Gürsel, D. The emergence of the enterprising refugee discourse and differential inclusion in Turkey’s changing migration politics. Mov. J. Crit. Migr. Bord. Regime Stud. 2017, 3, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Omata, N. Who takes advantage of mobility? Exploring the nexus between refugees’ movement, livelihoods and socioeconomic status in West Africa. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2017, 37, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, B. Migration and the formation of transnational economic networks between Africa and Turkey: The socio-economic establishment of migrants in situ and in mobility. Afr. Black Diaspora Int. J. 2017, 10, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fass, S. Innovations in the struggle for self-reliance: The Hmong experience in the United States. Int. Migr. Rev. 1986, 20, 351–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyares, I.M. Little Odessa—Brighton Beach, Brooklyn: An examination of the former Soviet refugee economy in New York City. Urban. Geogr. 1998, 19, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.J. Ethnic differences in self-employment among Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2000, 38, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert, D. The spatial limits to entrepreneurship: Immigrant entrepreneurs in Canada. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En. Soc. Geogr. 2002, 93, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A. Buddha is Hiding: Refugees, Citizenship, the New America; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kibreab, G. Citizenship rights and repatriation of refugees. Int. Migr. Rev. 2003, 37, 24–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamgain, V.; Collins, K. Off the boat, now off to work: Refugees in the labour market in Portland, Maine. J. Refug. Stud. 2003, 16, 113–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Love, N.; Lim, L.; Akehurst, G. Guest editorial: Female and ethnic minority entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2006, 2, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.H. Economic globalization from below: Transnational refugee trade networks in Nairobi cities in contemporary Africa. In Cities in Contemporary Africa; Murray, M.J., Myers, G.A., Eds.; Palgrave McMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Abt, C.C. Helping young immigrants/refugees become entrepreneurs. In Helping Young Refugees and Immigrants Succeed; Sonnert, G., Holton, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ranalli, B. Local currencies: A potential solution for liquidity problems in refugee camp economies. J. Refug. Stud. 2014, 27, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilcan, S.; Rygiel, K. Resiliency humanitarianism: Responsibilizing refugees through humanitarian emergency governance in the camp. Int. Political Sociol. 2015, 9, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujaki, M.L.; Gaudet, S.; Iuliano, R.M. Governmentality and identity construction through 50 years of personal income tax returns: The case of an immigrant couple in Canada. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2017, 46, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.; Coenen, F. Immigrant entrepreneurship—A chance for labor market integration of refugees. In Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Skills in Europe: Examples to Improve Potential Entrepreneurial Spirit; Hamburg, I., David, A., Eds.; Barbara Budrich Publishers: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship. In Little Ethiopia of the Pacific Northwest; Scott, J.W., Getahun, S.A., Eds.; Routledge Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Chapter 4; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, T.; Aldrich, H.E.; Liou, N. Invisible entrepreneurs: The neglect of women business owners by mass media and scholarly journals in the USA. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1997, 9, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, E.F. The refugee in flight: Kinetic models and forms of displacement. Int. Migr. Rev. 1973, 7, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, L.; Syrett, S.; Lyon, F. Population superdiversity and new migrant enterprise: The case of London. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2011, 23, 469–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbrunn, S. Against all odds: Refugees bricoleuring in the void. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1045–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, E.F. Part II: The analytic framework: Exile and resettlement: Refugee theory. Int. Migr. Rev. 1981, 15, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Volery, T. Ethnic entrepreneurship: A theoretical framework. In Handbook of Research on Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship: A Co-Evolutionary View on Resource Management; Dana, L.-P., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; pp. 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Riddle, L.; Brinkerhoff, J. Diaspora entrepreneurs as institutional change agents: the case of Thamel.com. Int Bus Rev. 2011, 20, 670–680. [Google Scholar]

- Schøtt, T. Entrepreneurial pursuits in the Caribbean diaspora: Networks and their mixed effects. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 30, 1069–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Baklanov, N.; Rezaei, S.; Vang, J.; Dana, L.-P. Migrant entrepreneurship, economic activity and export performance: Mapping the Danish trends. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2014, 23, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basok, T. Keeping Heads Above Water: Salvadorean Refugees in Costa Rica; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tawodzera, G.; Chikanda, A.; Crush, J.; Tengeh, R. International Migrants and Refugees in Cape Town’s Informal Economy; Migration Policy Series No. 70.; Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), Megadigital: Cape Town, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Crush, J.; Tawodzera, G. Refugee entrepreneurial economies in urban South Africa. In African Human Mobility Review; Special Issue; Southern African Migration Programme: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2017; pp. 783–819. [Google Scholar]

- Welter, F. Contextualizing entrepreneurship—Conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, J. Forward. In Refugee Entrepreneurship: A Case Based Topography; Heilbrunn, S., Freiling, J., Harima, A., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2018; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dajani, H.; Marlow, S. Impact of women’s home-based enterprise on family dynamics: Evidence from Jordan. Int. Small Bus. J. 2010, 28, 470–486. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dajani, H.; Carter, S. Women empowering women: Female entrepreneurs and home-based producers in Jordan. Women Entrepreneurs and the Global Environment for Growth: A Research Perspective 2010, 118–137. [Google Scholar]

- Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion. The World’s Stateless; Wolf Legal Publishers: Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Villares-Varela, M.; Essers, C. Women in the migrant economy. A positional approach to contextualize gendered transnational trajectories. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, A.; Bloom, L.; Weaver, N. Refugee Innovation: Humanitarian Innovation That Starts with Communities; Humanitarian Innovation Project; University of Oxford: Oxford, MS, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, A.; Bloom, L.; Kaplan, J.; Omata, N. Rethinking popular assumptions. In Refugee Economies; Humanitarian Innovation Project; University of Oxford: Oxford, MS, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, A. Refugees’ Opportunities and Barriers in Employment and Training; Research Report No 179; Goldsmith College, University of London on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions, Charlesworth Group: Huddersfield, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J. From Refugee to Entrepreneur in Sydney in Less than Three Years: Final Evaluation Report on the SSI Ignite Small Business Start-Ups Program; UTS Business School: Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Desiderio, M.V. Integrating Refugees into Host Country Labor Markets: Challenges and Policy Options; Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Else, J.; Krotz, D.; Budzilowics, L. Refugee Microenterprise Development: Achievements and Lessons Learned, 2nd ed.; ISED Solutions: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, M.A.; Rodríguez, N.M.; Conrad, A. Small Business Development in Iowa: A Research Report with Recommendations; New Iowans Program; University of Iowa: Cedar Falls, IA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Labour Market Integration of Refugees in Germany; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Author(s) | Worldwide Citation Count | Cross-Citations Among the Pool of Our Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | Ong | 1100 | 0 |

| 1992a | Gold (Book) | 427 | 7 (Gold, 1991 [as forthcoming], 1994, 2014; Johnson, 2000; Miyares, 1998; Sheridan, 2008; Smith-Hefner, 1995) |

| 2003 | Kibreab | 77 | 0 |

| 1997 | Kaplan | 70 | 0 |

| 1988 | Gold | 68 | 9 (Gold, 1991, 1992a, 1992b, 1994; Halter, 1995; Miyares, 1998; Wauters and Lambrecht, 2006, 2007, 2008) |

| 1994 | Gold | 58 | 1 (Halter, 1995) |

| 1991 | Gold | 55 | 1 (Mamgain and Collins, 2003) |

| 2003 | Mamgain and Collins | 47 | 0 |

| 2000 | Johnson | 40 | 0 |

| 2002 | Hiebert | 38 | 0 |

| 2006 | Fuller-Love, Lim and Akehurst | 33 | 0 |

| 1986 | Fass | 31 | 0 |

| 2009 | Halkias et al. | 27 | 0 |

| 2003 | Serdedakis, Tsiolis, Tzanakis and Papaioannou | 23 | 0 |

| 1993 | Basok | 22 | 1 (Kibreab, 2003) |

| 2007 | Lyon, Sepulveda and Syrett | 21 | 2 (Kachkar, Mohammed, Saad and Kayadibi, 2016; Raijman and Barak-Bianco, 2015) |

| 2008 | Wauters and Lambrecht | 19+ | 3 (Bizri, 2017; Raijman and Barak-Bianco, 2015; Sandberg, Immonen and Kok, 2018) |

| 1992b | Gold (Journal) | 19 | 7 (Fong et al., 2007; Fuller-Love, Lim and Akehurst, 2006; Raijman and Barak-Bianco, 2015; Tömöry, 2008; Wauters and Lambrecht, 2006, 2007, 2008) |

| 2007 | Fong et al. | 18+ | 1 (Sandberg, Immonen and Kok, 2018) |

| 2013 | Hugo | 16 | 0 |

| 1998 | Miyares | 14 | 0 |

| 2015 | Ilcan and Rygiel | 13 | 0 |

| 2006 | Wauters and Lambrecht | 11+ | 4 (Fuller-Love, Lim and Akehurst, 2006; Lyon, Sepulveda and Syrett, 2007; Sandberg, Immonen and Kok, 2018; Wauters and Lambrecht, 2008) |

| 1989 | Basok | 10 | 1 (Basok, 1993) |

| 2015 | Beehner | 10 | 0 |

| 2007 | Campbell | 8 | 0 |

| 1992 | LaTowsky and Grierson | 7 | 0 |

| 1995 | Smith-Hefner | 5 | 0 |

| 2014 | Gold | 5 | 0 |

| 2007 | Wauters and Lambrecht | 4+ | 1 (Sandberg, Immonen and Kok, 2018) |

| 1990 | Moore | 4 | 0 |

| 1994 | Singh | 4 | 0 |

| 1995 | Halter | 4 | 1 (Gold 1994 [as in press]) |

| 2013 | Sabar and Posner | 4 | 1 (Raijman and Barak-Bianco, 2015) |

| 2014 | Ranalli | 4 | 0 |

| 2014 | Şaul | 4 | 0 |

| 2012 | Dana | 3 | 0 |

| 2014 | Omeje and Mwangi | 3 | 0 |

| 2016 | Abdel Jabbar and Ibrahim Zaza | 3 | 0 |

| 2008 | Sheridan | 2 | 0 |

| 2008 | Tömöry | 2 | 0 |

| 2015 | Raijman and Barak-Bianco | 2 | 0 |

| 2017 | Betts, Omata and Bloom | 2 | 0 |

| 2017 | David and Coenen | 2 | 0 |

| 2017 | Lankov, Ward, Yoo and Kim | 2 | 0 |

| 2017 | Suter | 2 | 0 |

| 2016 | Elo and Vemuri | 1+ | 1 (Sandberg, Immonen and Kok, 2018) |

| 2006 | Garnham | 1 | 0 |

| 2014 | Călin-Ştefan | 1 | 0 |

| 2014 | Pulla and Kharel | 1 | 0 |

| 2015 | De Jager | 1 | 0 |

| 2015 | Northcote and Dodson | 1 | 0 |

| 2016 | Kachkar, Mohammed, Saad and Kayadibi | 1 | 0 |

| 2016 | van Kooy | 1 | 0 |

| 2018 | Sandberg, Immonen and Kok | 1 | 1 (Bizri, 2017) |

| The following 13 publications had not yet been cited (to the end of 2017): Abt, 2010; Ayadurai, 2011; Bizri, 2017; Bujaki, Gaudet and Iuliano, 2017; Crush and McCordic, 2017; Crush, Tawodzera, McCordic and Ramachandran, 2017; Forrest and Balos, 2013; Gonzales, Gürsel, 2017; Kachkar, 2017; Morais, 2014; Omara, 2017; Sánchez Piñeiro and Saavedra, 2016; Scott and Getahun, 2017. | |||

| Author(s), Year | COO | Data | COR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abt, 2010 | Central Europe, Former Soviet, and Liberia | Data from the 1930s to 2010 | USA |

| Dana, 2012 | Syria | Historical and Post-WWII | Egypt and USA |

| Moore, 1990 | Germany | Data from the 1930s | Netherlands |

| Tömöry, 2008 | Hungary and Cuba | Hungarian arrivals in 1956 and Cuban arrivals in 1959 | Canada |

| Bujaki, Gaudet and Iuliano, 2017 | Hungary | Data from 1958–2011 | Canada |

| Halter, 1995 | Former Soviet Union | Data from 1975–1986 | USA |

| Gold, 1991 | Vietnam | Data from 1982–1989 | USA |

| Gold, 2014 | Former Soviet Union, Israel and Vietnam | Data from 1982–1994 | France, Israel, UK and USA |

| Fass, 1986 | Hmong (China, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and Thailand) | Data from 1983 | USA |

| Gold 1994 | Former Soviet Union | Data from the early-1980s to the early-1990s | USA |

| Gold, 1988, 1992a, 1992b | Former Soviet Union and Vietnam | Data from the early-1980s to the early-1990s | USA |

| Smith-Hefner, 1995 | Cambodia (Sino-Khmer) | Data from 1991 | USA |

| Johnson, 2000 | Vietnam (Boat People) and Laos | Data from 1991–1993 | Canada |

| Miyares, 1998 | Former Soviet Union | Data from 1993–1994 | USA |

| Serdedakis, Tsiolis, Tzanakis and Papaioannou, 2003 | Former Soviet Union | Data from 1997–2000 | Greece |

| Lankov, Ward, Yoo and Kim, 2017 | North Korea | Data from the late-1990s to 2011 | South Korea |

| Elo and Vemuri, 2016 | Post-Soviet Bukharians (Central Asia) | Data from 2012–2015 | Israel, Germany and USA |

| Author(s), Year | COO | Data | COR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morais, 2014 | African | Arrivals 1987–2008, data collected 2011–2013 | Macao S.A.R. and Portugal |

| Kibreab, 2003 | Various | Not specified, but <2003 | Various |

| David and Coenen, 2017 | Various | Not specified, but <2017 | Germany and the Netherlands |

| Scott and Getahun, 2017 | Ethiopia | Arrivals in the late-1960s to the early-1970s, data collected <2017 | USA |

| Ong, 2003 | Cambodia and Southeast Asia | Data from the 1980s | USA |

| Sheridan, 2008 | Vietnam | Data from the early- 1980s and the 1990s | Ireland |

| Kaplan, 1997 | Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos | Data from the 1990s | USA |

| Hiebert, 2002 | Various | Data from the mid-1990s to the late 1990s | Canada |

| Sandberg, Immonen and Kok, 2018 | Palestine, Iraq, Iran and Vietnam | Arrivals in the 1970s and in the 2000s, data from <2016 | Sweden |

| Hugo, 2013 | Various | Data from 1993–2009 | Australia |

| Wauters and Lambrecht, 2006, 2007, 2008 | Various | Data from 1997–2003 | Belgium |

| Mamgain and Collins, 2003 | Various | Data from 2000–2003 | USA |

| Fuller-Love, Lim and Akehurst, 2006 | Various | Not specified, but <2006 | Various |

| Garnham, 2006 | Various | Not specified, but <2006 | New Zealand |

| Fong et al., 2007 | Cuba, Iran, Macedonia and Nigeria | Not specified, but <2007 | USA |

| Lyon, Sepulveda and Syrett, 2007 | Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Somalia and Sudan | Not specified, but <2007 | UK |

| Halkias et al., 2009 | Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and other African countries | Not specified, but <2009 | Greece |

| Gonzales, Forrest and Balos, 2013 | Iraq, Somalia, Togo and Uzbekistan | Data from 2012 | USA |

| van Kooy, 2016 | Various | Data from 2015 | Australia |

| Author(s), Year | COO | Data | COR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singh, 1994 | Pakistan | Data from the late 1940s to the early 1990s | India |

| Basok, 1989, 1993 | El Salvador | Data from 1985–1986 | Costa Rica |

| LaTowsky and Grierson, 1992 | Various | Data from 1985–1987 | Somalia |

| Ranalli, 2014 | Various | Data from 2000–2013 | Kenya and the Netherlands |

| Campbell, 2007 | Burundi, D. R. C., Ethiopia, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan and Uganda | Data from 2003–2004 | Kenya |

| Ilcan and Rygiel, 2015 | Various | Data from 2005–2015 | Various |

| Suter, 2017 | Burundi, D. R. C., Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria and Sudan | Data from 2007–2009 | Turkey |

| Sabar and Posner, 2013 | Eritrea and Sudan | Data from 2009–2011 | Israel |

| Ayadurai, 2011 | Afghanistan, Myanmar, Somalia and Sri Lanka | Data from 2010 | Malaysia |

| Omeje and Mwangi, 2014 | Somalia | Data from 2011 | Kenya |

| Abdel Jabbar and Ibrahim Zaza, 2016 | Syria | Data from 2011–2012 | Jordan |

| Călin-Ştefan, 2014 | Syria | Data from 2011–2014 | Armenia |

| Pulla and Kharel, 2014 | Tibet | Data from 2012 | Nepal |

| Beehner, 2015 | Syria | Data from 2012–2013 | Jordan |

| De Jager, 2015 | Various | Data from 2012–2015 | South Africa |

| Betts, Omata and Bloom, 2017 | Various African countries | Data from 2013 | Uganda |

| Northcote and Dodson, 2015 | Continental Africa | Data from 2013 | South Africa |

| Şaul, 2014 | Sub-Saharan Africa | Not specified, but <2014 | Turkey |

| Gürsel, 2017 | Syria | Data from 2014–2016 | Turkey |

| Raijman and Barak-Bianco, 2015 | Eritrea and Sudan | Not specified, but <2015 | Israel |

| Sánchez Piñeiro and Saavedra, 2016 | Columbia | Data from 2016 | Ecuador |

| Kachkar, Mohammed, Saad and Kayadibi, 2016 | Various | Not specified, but <2016 | Malaysia |

| Kachkar, 2017 | Various | Not specified, but <2017 | Various |

| Crush and McCordic, 2017 | Various | Not specified, but <2017 | South Africa |

| Crush, Tawodzera, McCordic and Ramachandran, 2017 | Various | Not specified, but <2017 | South Africa |

| Bizri, 2017 | Syria | Not specified, but <2017 | Lebanon |

| Omata, 2017 | Liberia | Not specified, but <2017 | Ghana |

| Research Objectives and Highlighted Themes | Sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 (Table 2) | Wave 2 (Table 3) | Wave 3 (Table 4) | |

| Characteristics of Refugee Entrepreneurship | Abt, 2010; Bujaki, Gaudet and Iuliano, 2017; Dana, 2012; Elo and Vemuri, 2016; Gold, 1988, 1992a, 1992b, 1994; Halter, 1995; Johnson, 2000; Lankov, Ward, Yoo and Kim, 2017; Moore, 1990; Morais, 2014; Smith-Hefner, 1995; Tömöry, 2008 | Fong et al., 2007; Fuller-Love, Lim and Akehurst, 2006; Garnham, 2006; Halkias et al., 2009; Kaplan, 1997; Lyon, Sepulveda and Syrett, 2007; Mamgain and Collins, 2003; Ong, 2003; Sandberg, Immonen and Kok, 2018; Sheridan, 2008; Wauters and Lambrecht, 2006, 2007, 2008 | Basok, 1989, 1993; Bizri, 2017; Campbell, 2007; Crush and McCordic, 2017; Crush, Tawodzera, McCordic and Ramachandran, 2017; Gürsel, 2017; Ilcan and Rygiel, 2015; Northcote and Dodson, 2015; Singh, 1994 |

| Differences Between Refugee and Immigrant Entrepreneurs/hip | Gold, 1988, 1992b, 2014; Johnson, 2000 | Garnham, 2006; Hiebert, 2002; Hugo, 2013; Kaplan, 1997; Mamgain and Collins, 2003; Ong, 2003; Sandberg, Immonen and Kok, 2018; Wauters and Lambrecht, 2007, 2008 | Crush and McCordic, 2017 |

| Type of Businesses/ Economic/Social Activities Being Established/ Employed | Dana, 2012; Gold, 1988, 1992a, 1992b, 2014; Halter, 1995; Johnson, 2000; Lankov, Ward, Yoo and Kim, 2017; Miyares, 1998; Morais, 2014 | Gonzales, Forrest and Balos, 2013; Halkias et al., 2009; Kaplan, 1997; Ong, 2003; Sandberg, Immonen and Kok, 2018; Scott and Getahun, 2017; Sepulveda, Syrett and Lyon, 2011; Wauters and Lambrecht, 2007 | Basok, 1989, 1993; Bizri, 2017; Campbell, 2007; Crush and McCordic, 2017; Crush, Tawodzera, McCordic and Ramachandran, 2017; Pulla and Kharel, 2014; Raijman and Barak-Bianco, 2015; Sabar and Posner, 2013; Şaul, 2014; Singh, 1994 |

| Challenges Faced by Refugee Entrepreneurs and Organizations Dealing with Refugee Entrepreneurship | Elo and Vemuri, 2016; Gold, 1988, 1992a, 1992b; 1994, 2014; Morais, 2014; Serdedakis, Tsiolis, Tzanakis and Papaioannou, 2003 | David and Coenen, 2017; Fong et al., 2007; Garnham, 2006; Halkias et al., 2009; Lyon, Sepulveda and Syrett, 2007; Ong, 2003; Sandberg, Immonen and Kok, 2018; Scott and Getahun, 2017; Sheridan, 2008; Wauters and Lambrecht, 2006, 2007, 2008 | Ayadurai, 2011; Basok, 1989, 1993; Betts, Omata and Bloom, 2017; Bizri, 2017; Campbell, 2007; Crush, Tawodzera, McCordic and Ramachandran, 2017; De Jager, 2015; Ilcan and Rygiel, 2015; Kachkar, 2017; Kachkar, Mohammed, Saad and Kayadibi, 2016; Northcote and Dodson, 2015; Omata 2017; Omeje and Mwangi, 2014; Pulla and Kharel, 2014; Raijman and Barak-Bianco, 2015; Ranalli, 2014; Şaul, 2014 |

| Entrepreneurial Intentions of Refugees and Training Programs/ Assistance for Refugees | Gold, 1988, 1992b, 1994, 2014; Fass, 1986; Halter, 1995; Johnson, 2000; Miyares, 1998; Morais, 2014; Serdedakis, Tsiolis, Tzanakis and Papaioannou, 2003; Tömöry, 2008 | Mamgain and Collins, 2003; Ong, 2003; Scott and Getahun, 2017; van Kooy, 2016; Wauters and Lambrecht, 2006, 2007, 2008 | Abdel Jabbar and Ibrahim Zaza, 2016; Crush and McCordic, 2017; Kachkar, 2017; Kachkar, Mohammed, Saad and Kayadibi, 2016; LaTowsky and Grierson, 1992; Omata 2017; Raijman and Barak-Bianco, 2015; Ranalli, 2014; Sánchez Piñeiro and Saavedra, 2016; Singh, 1994 |

| Policy Issues | Fass, 1986; Lankov, Ward, Yoo and Kim, 2017; Miyares, 1998; Moore, 1990; Serdedakis, Tsiolis, Tzanakis and Papaioannou, 2003; Tömöry, 2008 | David and Coenen, 2017; Garnham, 2006; Halkias et al., 2009; Kibreab, 2003; Lyon, Sepulveda and Syrett, 2007; van Kooy, 2016; Wauters and Lambrecht, 2008 | Basok, 1989, 1993; Beehner, 2015; Călin-Ştefan, 2014; Campbell, 2007; Crush and McCordic, 2017; Gürsel, 2017; Ilcan and Rygiel, 2015; Kachkar, Mohammed, Saad and Kayadibi, 2016; Omeje and Mwangi, 2014; Raijman and Barak-Bianco, 2015; Ranalli, 2014; Sánchez Piñeiro and Saavedra, 2016 |

| Impact of Refugee Entrepreneurship (e.g., on the new COR, societies, sense making, etc.) | Elo and Vemuri, 2016; Gold, 1991, 1992a, 1992b, 1994, 2014; Johnson, 2000; Moore, 1990; Serdedakis, Tsiolis, Tzanakis and Papaioannou, 2003; van Kooy, 2016 | David and Coenen, 2017; Garnham, 2006; Gonzales, Forrest and Balos, 2013; Hugo, 2013; Kaplan, 1997; Lyon, Sepulveda and Syrett, 2007; Mamgain and Collins, 2003; Ong, 2003; Sheridan, 2008; Wauters and Lambrecht, 2006, 2007, 2008 | Abdel Jabbar and Ibrahim Zaza, 2016; Basok, 1989, 1993; Crush and McCordic, 2017; Crush, Tawodzera, McCordic and Ramachandran, 2017; Ilcan and Rygiel, 2015; Pulla and Kharel, 2014; Sabar and Posner, 2013; Sánchez Piñeiro and Saavedra, 2016; Şaul, 2014; Suter, 2017 |

| Camp Economies and Refugee Businesses; Livelihoods | Betts, Omata and Bloom, 2017; Ilcan and Rygiel, 2015; Northcote and Dodson, 2015; Omata 2017; Ranalli, 2014 | ||

| Methods Used | Number (Total 68) | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative methods (e.g., ethnography, field observations, focus groups, interviews) | 39 | 57.5% |

| Quantitative methods (e.g., statistics, surveys) | 9 | 13.2% |

| Mixed methods | 9 | 13.2% |

| Other or not relevant | 11 | 16.1% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heilbrunn, S.; Iannone, R.L. From Center to Periphery and Back Again: A Systematic Literature Review of Refugee Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187658

Heilbrunn S, Iannone RL. From Center to Periphery and Back Again: A Systematic Literature Review of Refugee Entrepreneurship. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187658

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeilbrunn, Sibylle, and Rosa Lisa Iannone. 2020. "From Center to Periphery and Back Again: A Systematic Literature Review of Refugee Entrepreneurship" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187658

APA StyleHeilbrunn, S., & Iannone, R. L. (2020). From Center to Periphery and Back Again: A Systematic Literature Review of Refugee Entrepreneurship. Sustainability, 12(18), 7658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187658