1. Introduction

Promoting sustainable production and consumption and embracing circularity in the supply chain have emerged as the most pressing issues facing the manufacturing industry [

1,

2]. Remanufacturing can be an effective solution to overcome this challenge [

3]. Remanufacturing is a process of returning used products to a like-new state by reconditioning or replacing their component parts [

4,

5]. It enables the manufacturing companies to offer more affordable and greener products to the market and helps them comply with environmental legislation and regulations [

6]. Accordingly, remanufacturing has gained increasing attention in various fields, such as electronics, machinery and equipment, aerospace and automotive, and furniture, as a means of facilitating a circular economy and a method to achieve both economic and environmental sustainability [

7].

However, despite its growing importance and popularity, many companies, especially in the consumer-goods market, are reluctant to implement remanufacturing [

8]. One of the major challenges in remanufacturing of consumer goods is the lack of knowledge about the consumer market. Especially, research on consumer valuation of remanufactured products (what consumers think of the remanufactured products and how they value them) is still in its infancy [

9,

10,

11].

Previous studies on consumer valuation have focused on identifying the factors influencing the consumers’ purchase intention or their willingness to pay (WTP) for a remanufactured product. Previous studies have found that both the consumer characteristics (greenness, attitude, knowledge, involvement, etc.) and the product attributes (brand, price, warranty, etc.) are among the major factors influencing the value of remanufactured products [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. However, only a few studies have investigated the influences of product categories and business models. Most studies have dealt with a single category of products, which makes it difficult to compare the suitability of different product categories for remanufacturing business. More importantly, most previous studies have considered only the buying model where the consumers purchase and own the product. Although rental and sharing (hereinafter referred to as the rental model) are gaining increasing interest as alternative business models to buying [

22,

23,

24], relatively little is known about the effect of the business models on the consumer valuation and acceptance of remanufactured products.

The purpose of this study is to test the effects of product categories and business models on the consumer valuation of remanufactured products empirically. Certain product categories can be naturally more attractive to consumers in the remanufactured goods market and more likely to be accepted at a higher price. Identifying such categories of appropriateness to remanufacturing is necessary and valuable for successful remanufacturing businesses. Clarifying the suitability of the rental model for remanufactured products also provides useful insights for remanufacturing businesses. It helps explore new business opportunities in the rental market. A comparative study of product categories and business models is necessary in this regard. To the best knowledge of the authors, the current study is the first of its kind highlighting the effect of product categories and business models together.

More specifically, this study presents a survey on the relative value of remanufactured products (i.e., the value of remanufactured products compared to their original new versions) to address the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: Does the product category influence the relative value of remanufactured products? From the consumer-demand perspective, which product categories are more appropriate for remanufacturing?

RQ2: Does the business model make any difference in the relative value of the remanufactured product? Can the rental model be recommended to the remanufacturing business?

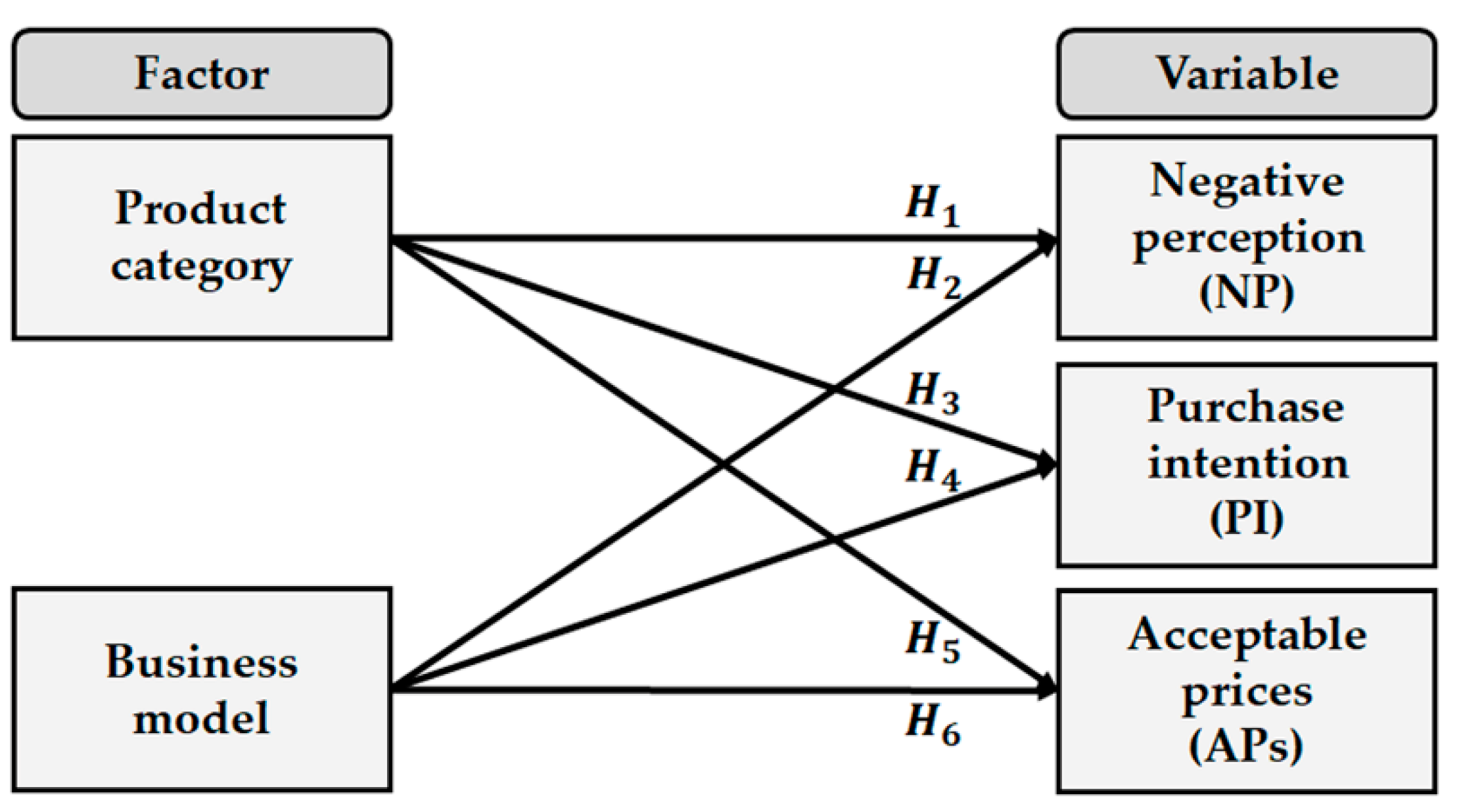

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the survey. Product categories and business models are the two factors of interest. In this study, six product categories that represent a variety of personal and home electronics were chosen for the survey. These were low-end laptops, high-end laptops, smartphones, gaming consoles, printers, and water purifiers. The existence of active rental markets and the familiarity of the intended participants (university students in South Korea) with the categories were reflected in selecting the categories. The number of categories was determined considering the response burden on the participants. For the business models, the two most popular cases were considered: the buying and the rental models.

The dependent variable is the relative value of the remanufactured products. In this study, it was assessed from three different perspectives: negative perception (NP), purchase intention (PI), and acceptable prices (APs).

Table 1 shows the definition of the dependent variables. NP and PI are the concepts that frequently appear in the literature (e.g., [

12,

18,

21,

25]). APs, adopted from the Van Westendorp price sensitivity meter (PSM) [

26,

27], are an extended concept of WTP. Unlike previous studies that have focused only on the WTP, i.e., the too expensive price (e.g., [

20,

28,

29,

30]), this study examines various acceptable prices, including too cheap, cheap, reference, expensive, and too expensive prices, as well as the range of acceptable prices (

Figure 2). APs have been suggested as a measure of consumer valuation for the first time in this study.

The survey was conducted using a direct method [

27], providing the participants with the new product profile and asking them to write down the NP, PI, and APs for the remanufactured version of the product. The participants in the survey were 95 students from a Korean university. For the collected data, statistical testing was conducted. The chi-square test of independence was performed for NP and PI analyses, and the one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) and the

t-test were performed for AP analyses.

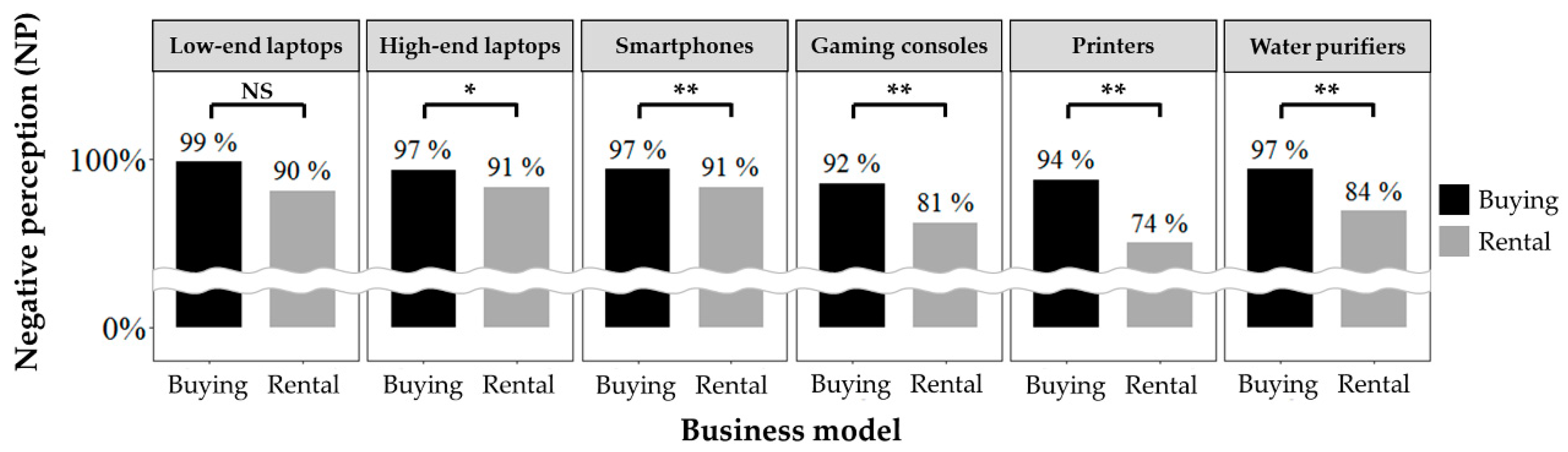

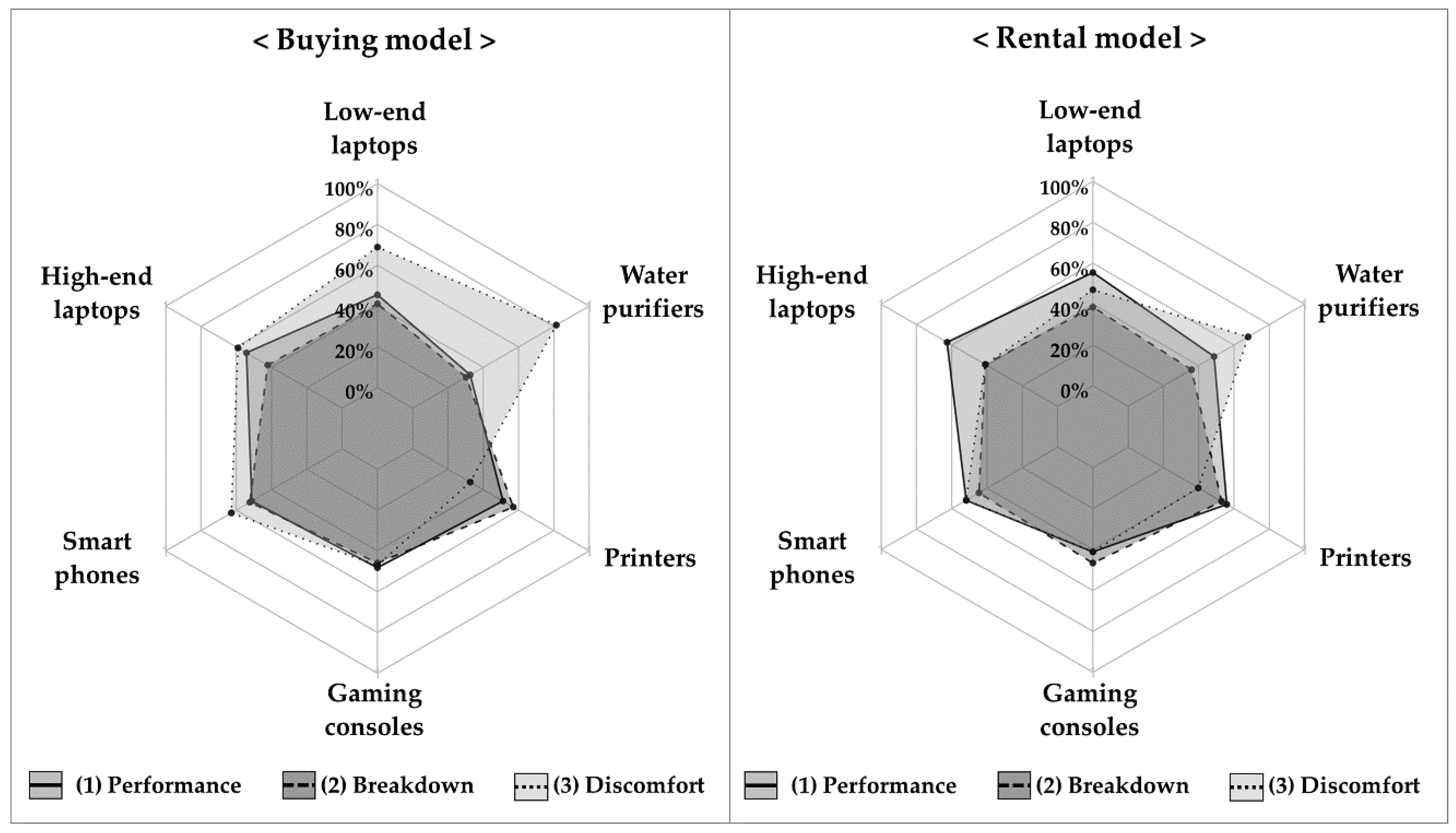

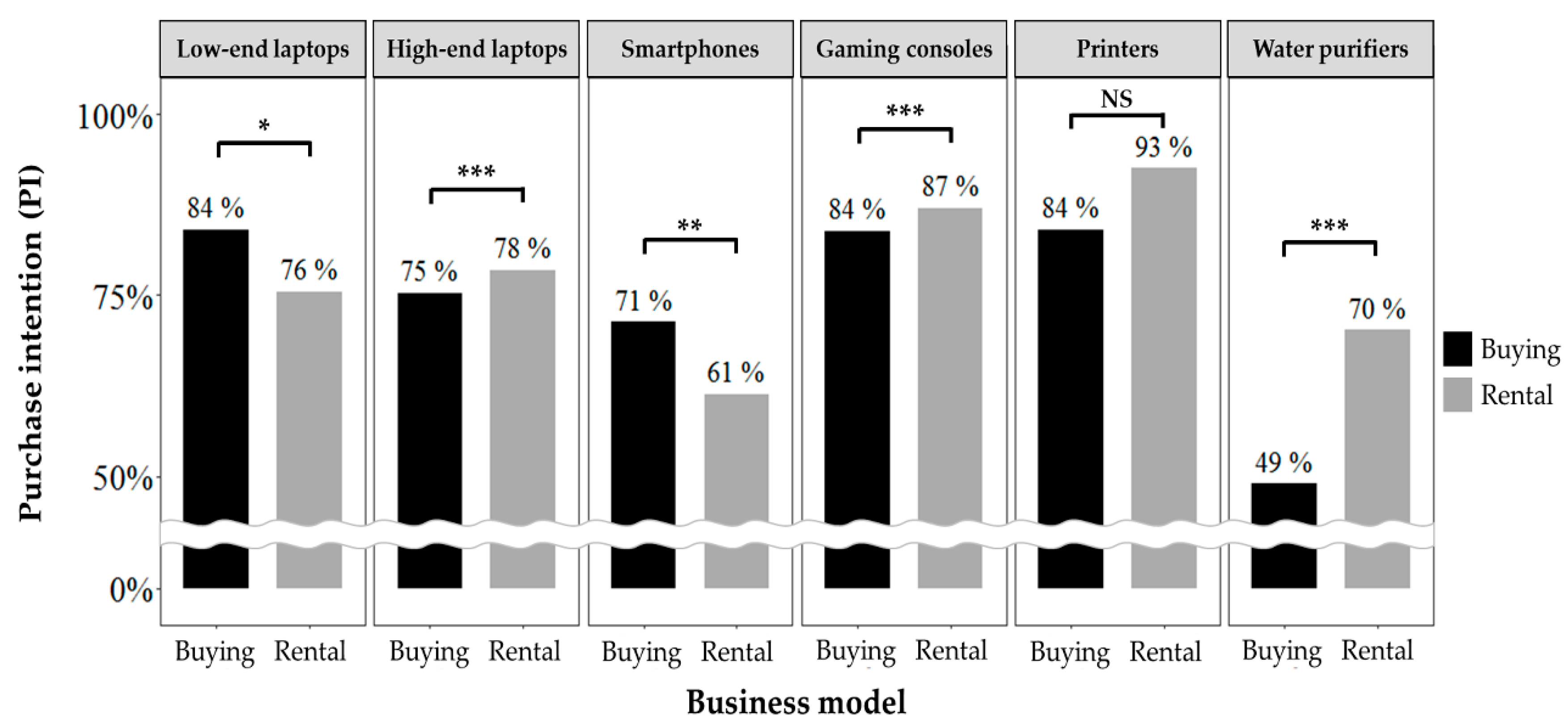

The survey results showed that both the product categories and the business models created a significant difference in the relative value of remanufactured products. In the buying model, some categories showed a lower NP and a higher PI, which implied greater market potential. It was observed that the mean difference in the too expensive price (maximum AP) was surprisingly not statistically significant among the product categories, however, the mean too cheap price (minimum AP) at which the consumers started doubting the product quality was revealed as significantly different. The results demonstrated that the market potential of remanufactured products varies across product categories, and there are product categories that are naturally more advantageous for remanufacturing than others are. When the business model was changed to rental, the NP, the PI, and the APs of all product categories differed significantly from the buying model. NP decreased in all categories, whereas PI showed different results depending on the product categories (decreasing in low-end laptops and smartphones, while increasing in others). The mean acceptable price ranges (APRs) increased in all the categories, which suggests either a decreased too cheap price (for laptops, smartphones, and water purifiers) or an increased too expensive price (for gaming consoles and printers). The results imply that suitability of the rental model varies across the product categories; for certain categories, the rental model can be a good option for the remanufacturing business.

The rest of the study is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature.

Section 3 describes the study method, including the hypotheses and the survey questionnaires.

Section 4,

Section 5,

Section 6 present the results, and

Section 7 discusses the implications of the results.

Section 8 concludes the study along with the future research directions.

2. Relevant Literature

From a process-flow perspective, remanufacturing consists of three processes: take-back of the used products, remanufacturing operations, and remarketing of the remanufactured products. For successful remanufacturing, all three processes should be managed and optimized in a coordinated manner [

31,

32]. Although significant research has been done on take-back management and remanufacturing operations, remarketing has received relatively less attention [

9,

11]. Especially, research on consumer valuation of remanufactured products is still in an early stage.

Table 2 shows a summary of the previous studies. Most previous studies have targeted identifying the factors influencing the consumers’ PI or WTP for remanufactured products.

2.1. PI for Remanufactured Products

Vazifehdoust et al. [

13] aimed to seek the factors that influence the PI in green products. This study showed that the consumers’ positive attitude was the critical factor in PI and attitude was significantly affected by the marketing variables such as the quality, green advertising, and green labeling. Jiménez-Parra et al. [

9] conducted a survey on the potential consumers of remanufactured laptops to gain an insight into the key drivers of their PI. The effects of attitude towards purchasing, subjective norm (i.e., social pressure), motivations (latest technology, cheap price, greenness), and marketing mix variables were investigated.

Wang et al. [

14] explored the factors that affect the consumers’ PI through an empirical study in the Chinese automobile spare parts industry. The results indicated that PI is directly influenced by the purchase attitude and the perceived behavioral control of consumers and indirectly influenced by perceived risk, perceived benefit, and product knowledge via attitude. Wang and Hazen [

15] examined how PI is affected by the consumer knowledge of the remanufactured products. It was found that consumer knowledge indirectly influences the PI via perceived value and risk. According to the research, PI is positively influenced by the perceived value and negatively influenced by the perceived risk. The perceived value is influenced by quality, cost, and green knowledge, and the perceived risk is influenced by quality and cost knowledge. Khor and Hazen [

10] studied how the consumer attitude, the subjective norms, and the perceived behavioral control affect the PI of remanufactured consumer electronic products. In addition, they discussed the difference between the consumer’s PI and the actual purchase behavior. Lack of knowledge about the greenness of remanufacturing, and negative perception towards the remanufactured condition were discussed as the possible reasons. Hazen et al. [

33] explored the consumer intention to switch from new to remanufactured products. The positive influences of new-product price, government incentive, environmental benefit, and attitude were observed. The moderating effect of attitude was also discussed. Wahjudi et al. [

34] investigated the factors that affect PI of remanufactured short-life cycle products like mobile phones. The results indicated that consumers’ attitudes and knowledge about the products have a positive impact on the PI. Additionally, the indirect impact of perceived benefit and perceived risk through attitude was noticed.

Bittar [

18] investigated the effect of brand equity and price ratio on PI. Both the factors were revealed as significant. It was also shown that the effect of brand equity becomes stronger when the price ratio is high compared to the case when it is low. Mugge et al. [

35] investigated differences between various customer groups concerning their evaluation of refurbished smartphones. Clustering was performed based on individual characteristics such as involvement, knowledge, innovativeness, value consciousness, environmental consciousness, social-adjustment function, and value-expressive function. Six distinct consumer groups were defined and the potential of incentives for increasing their purchase intention was discussed. Wang et al. [

16] examined the influence of green-attribute information of the remanufactured products (energy saving, material saving, and emission reducing) and the green certification on the consumers’ perceived green value and trust, and finally, the PI.

Milios and Matsumoto [

25] presented the results of a survey of Swedish consumers, analyzing their PI of remanufactured automotive parts. Consumers’ knowledge of remanufactured auto parts and their perception of associated benefits and risks were considered as the factors. The results revealed that Swedish consumers have limited knowledge about remanufactured auto parts, but nevertheless, they do recognize the benefits of using remanufactured auto parts. In contrary to most previous studies indicating consumers’ perceived risks as a negative factor, the authors highlighted that consumers are less preoccupied with the risks. Wang et al. [

36] proposed an advanced model identifying determinants of consumers’ PI of remanufactured products. Their factors were similar to those from other studies, but they differentiated consumers’ attitudes into experiential attitude and instrumental attitude, subjective norm into normative social influence and informational social influence, and perceived behavioral control into product knowledge, perceived risk, and perceived inconvenience. Interactions of the factors were also taken into account. They suggested that experiential and instrumental attitude, normative and informational social influence, product knowledge, and past experience are positive determinants of the PI, while perceived inconvenience and perceived risk are negative determinants.

2.2. WTP and Other Relevant Measures

Using an experimental auction, Michaud and Llerena [

30] investigated factors of WTP for remanufactured products. The study focused on the effect of four factors: the information about environmental impacts of production processes, informed environmental benefits of the product, proportion of remanufactured components, and identity of the remanufacturer. The study found that remanufactured products were valued less by the consumers compared to the new ones. Interestingly, informing consumers of the environmental benefits of remanufactured products did not increase the WTP of remanufactured ones, however, lowered the WTP of new ones.

Hazen et al. [

37] focused on the effect of consumers’ ambiguity tolerance and perceived quality on WTP. The study presented that ambiguity about remanufacturing makes consumers’ WTP decrease. As the ambiguity increases, consumers doubt the quality of products. Hamzaoui-Essoussi and Linton [

19] investigated the influence of newness, product category, and brand name on WTP. The WTP for greener (recycled/remanufactured), branded greener, and branded new products were compared. The findings suggested that WTP for greener products is largely affected by brand, and such brand effects are determined by the product category. Abbey et al. [

38] presented empirical studies on the role of perceived quality risk (perceived risk of functionality and cosmetic defects) on WTP. In addition, the study analyzed the variability of the WTP ratio (i.e., the ratio between WTP for a remanufactured product and WTP for a corresponding new product) among consumers.

Subramanian and Subramanyam [

20] analyzed eBay transaction data to find out drivers of price differentials between new and remanufactured products. It was found that seller reputation and authorized remanufacturers raise the price of remanufactured products. Abbey et al. [

11] examined the drivers of product attractiveness in the remanufactured consumer goods market. The effects of multiple factors including price discounts, brand equity, quality attributes, negative attributes, green attributes, and consumer greenness were discussed for three types of products: technology, household, and personal products.

Van Nguyen et al. [

39] developed a demand prediction model for remanufactured products using machine learning techniques. More than 5600 product listings on

www.Amazom.com were analyzed, and various factors were taken into account including positivity of product description, number of product pictures, warranty information disclosure, stock information, price difference between remanufactured and corresponding new products, product promotion rate, overall product rating, number of service failures and number of service successes, number of helpfulness votes, number of answered questions, average sentiment of customer reviews, and brand equity.

Lieder et al. [

40] analyzed the relationship between consumer demographic data and their choice of business models. Various business models having different payment schemes, environmental friendliness, and service levels were considered, including purchasing or renting a remanufactured product. Using both machine learning (support vector machine and simulation approaches), the choice behavior of a larger population was estimated based on the survey data of a small consumer group. As for the product category, a single category of washing machine was considered.

2.3. Contributions of the Current Study

Recent studies have shown that both consumer characteristics (such as attitude, subjective norms, product knowledge, greenness, risk aversion, involvement, etc.) and product attributes (such as price, green attributes, brand, remanufacturer identity, warranty, etc.) are the major determinants of PI and WTP. However, the possible influence of product categories and business models has gained relatively less attention in the previous studies.

As shown in

Table 2, most studies have dealt with a single category of products under the buying model with the product category and business model considered as control variables. This makes it complicated to address the RQs, i.e., the role of product categories (RQ1) and the role of business models (RQ2) in differentiating consumer valuation. Hamzaoui-Essoussi and Linton [

19], Subramanian and Subramanyam [

20], and Abbey et al. [

11] presented the exceptional studies that incorporated the effect of product categories. They pointed out that consumer valuation of remanufactured products varies with product category significantly. However, they considered only the WTP, price differential, and attractiveness, respectively, and none of them investigated the possible effects of business models as only the traditional buying model was considered. Although some researchers have projected that the rental model has a positive effect on the remanufacturing industry (e.g., [

8,

41,

42,

43]), its effects on the consumer valuation have not been investigated in detail. Lieder et al. [

40] presented a unique study taking into account various business models of a remanufactured product, but the effect of product category was not examined as the case was fixed to the example of washing machine.

This study can contribute to the literature, as it is a novel approach that demonstrates the effect of both product categories and business models on consumer valuation for remanufactured products. The inclusion of APs is another contribution. In contrast to other studies focusing only on the WTP (maximum AP), this study highlights the existence of other APs (too cheap, cheap, reference, expensive, and APR) and empirically tests its differences with respect to product category and business model. It is expected that the current study can demonstrate the product categories that are more suitable for remanufacturing. In addition, it is expected that this study can assist in clarifying the influence of the rental model on the remanufacturing business.

6. Result: Acceptable Prices (APs)

APs denote a range of prices that consumers think are acceptable for a remanufactured product. To identify the range of APs and to examine the reference price that the consumers consider reasonable, the survey asked four boundary prices: too cheap, cheap, expensive, and too expensive prices. The respondents who expressed positive PI were the participants. The too cheap and the too expensive prices correspond to the minimum and the maximum acceptable prices; here, the gap between the prices is defined as the APR. The cheap and the expensive prices provide the range of reasonable prices; the average of the prices is defined as the reference price.

For each product category, the survey first presented the new-product price and then directly asked for the APs using the PSM questionnaire. Detailed AP results are shown in

Table A4 and

Table A5 in

Appendix A. The obtained APs were converted to the relative values in percentage by dividing them with the new-product prices to compare the different product categories and the business models with various price levels. In other words, the AP of x% refers to the x% of the new-product price.

6.1. Buying Model

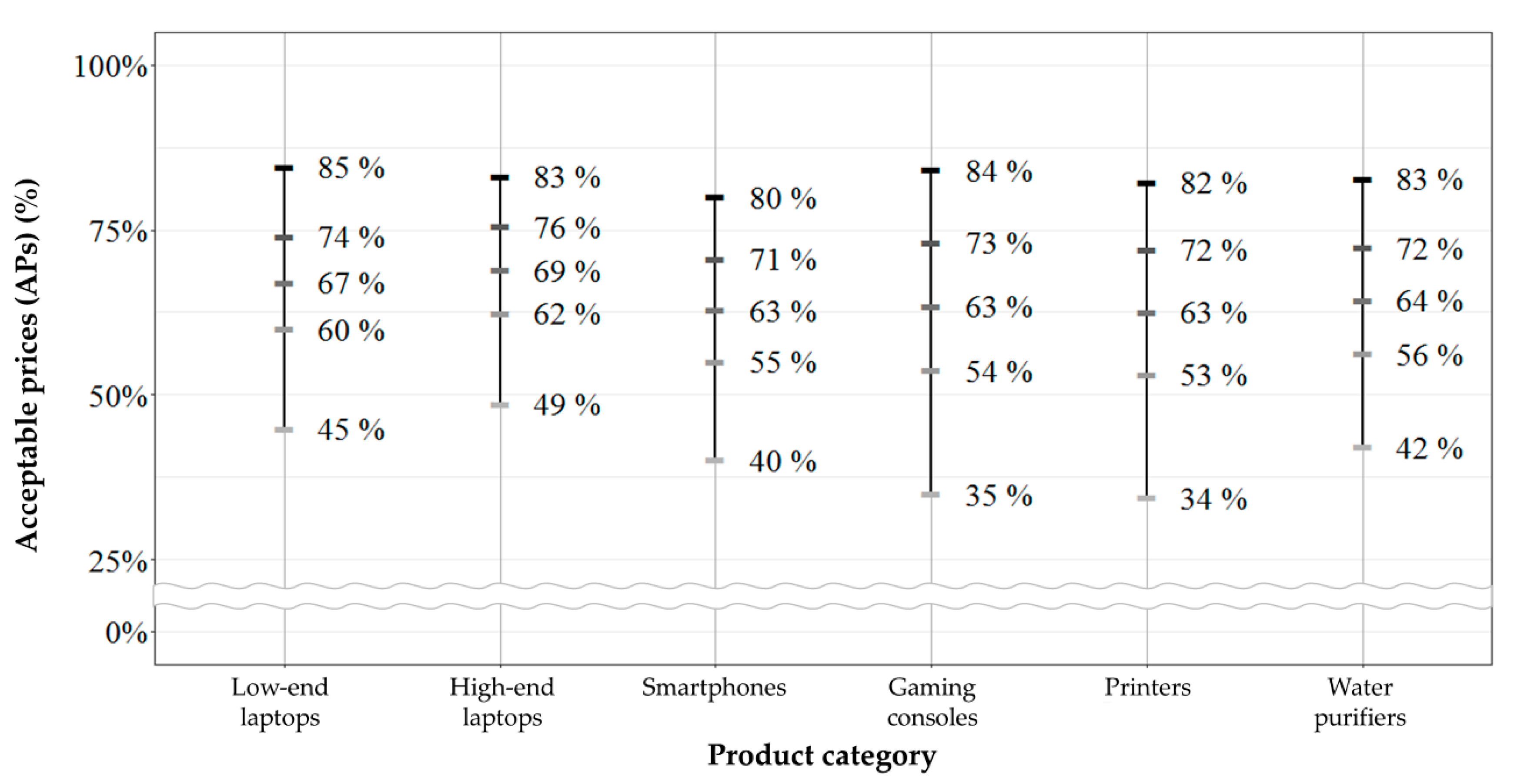

Figure 6 and

Table 13 show the mean APs under the buying model. To observe the variation of the mean APs with the product categories, a one-way ANOVA was conducted for each AP. Unlike the NP and the PI, APs showed less difference among the product categories, which is distinct.

First, the too cheap (

p-value = 0.000) and the cheap prices (

p-value = 0.005) showed significant differences among the product categories. The too cheap prices ranged from 34% (printers) to 49% (high-end laptops) and the cheap prices ranged from 53% (printers) to 62% (high-end laptops). Such differences led to significant differences in the APR (

p-value = 0.000), making it range from 35% (high-end laptops) to 49% (gaming consoles). As a post-hoc analysis,

Table 14 shows the Scheffe’s test results. The mean difference in the high-end laptops and the others (smartphone, gaming consoles, printers, and water purifiers) is the most significant. The gaming consoles and the printers showed too cheap and cheap prices lower than the laptop groups. The ANOVA and the post-hoc analysis results support hypotheses H

5a, H

5b, and H

5f under the buying model.

The difference in the too cheap price is especially interesting as it shows the boundary price at which the consumers begin questioning the product quality. In many remanufacturing studies, it has been assumed that lower prices lead to higher sales; however, the results show that this may not always be true. For instance, if a remanufactured high-end laptop is sold at 62% or below of the new-product price, consumers will doubt the quality and not buy the product. In other words, a decrease in sales is expected when the price is set too low. For the gaming consoles and the printers, however, a lower price still works. It seems that, unless the price is 34–35% or below, the consumers think the products are valid options for them.

In contrast to the too cheap and the cheap prices, the other prices showed no significant differences across the product categories. No significant differences were found in the reference (p-value = 0.587), the expensive (p-value = 0.096), and the too expensive prices (p-value = 0.725), rejecting hypotheses H5c, H5d, and H5e under the buying model. On an average, the consumers thought that 65% of the new-product price was reasonable for a remanufactured product; if the price was 73% or more of the new-product price, the consumers began to think the product was expensive, and if the price was 83% or more, they thought the product was too expensive and did not choose it. The result of the too expensive price was especially interesting. It implied that the worth the consumers placed on the remanufactured product was 83% of the new product and that it was indifferent across the six product categories.

6.2. Rental Model

Under the buying model, the too cheap prices, cheap prices, and APR were affected by the product category.

Table 15 shows that the difference as per the product category disappeared under the rental model. For all types of acceptable prices, too cheap (

p-value = 0.253), cheap (

p-value = 0.601), reference (

p-value = 0.798), expensive (

p-value = 0.842), and too expensive (

p-value = 0.441) prices, there exists no statistically significant difference among the six product categories. Accordingly, the APR showed no difference across the product categories (

p-value = 0.271). The category average showed that, regardless of the categories, consumers thought 33% of the new-product price was too cheap, 63% was reasonable, and 91% was too expensive. The results lead to the rejection of hypotheses H

5a through H

5e under the rental model.

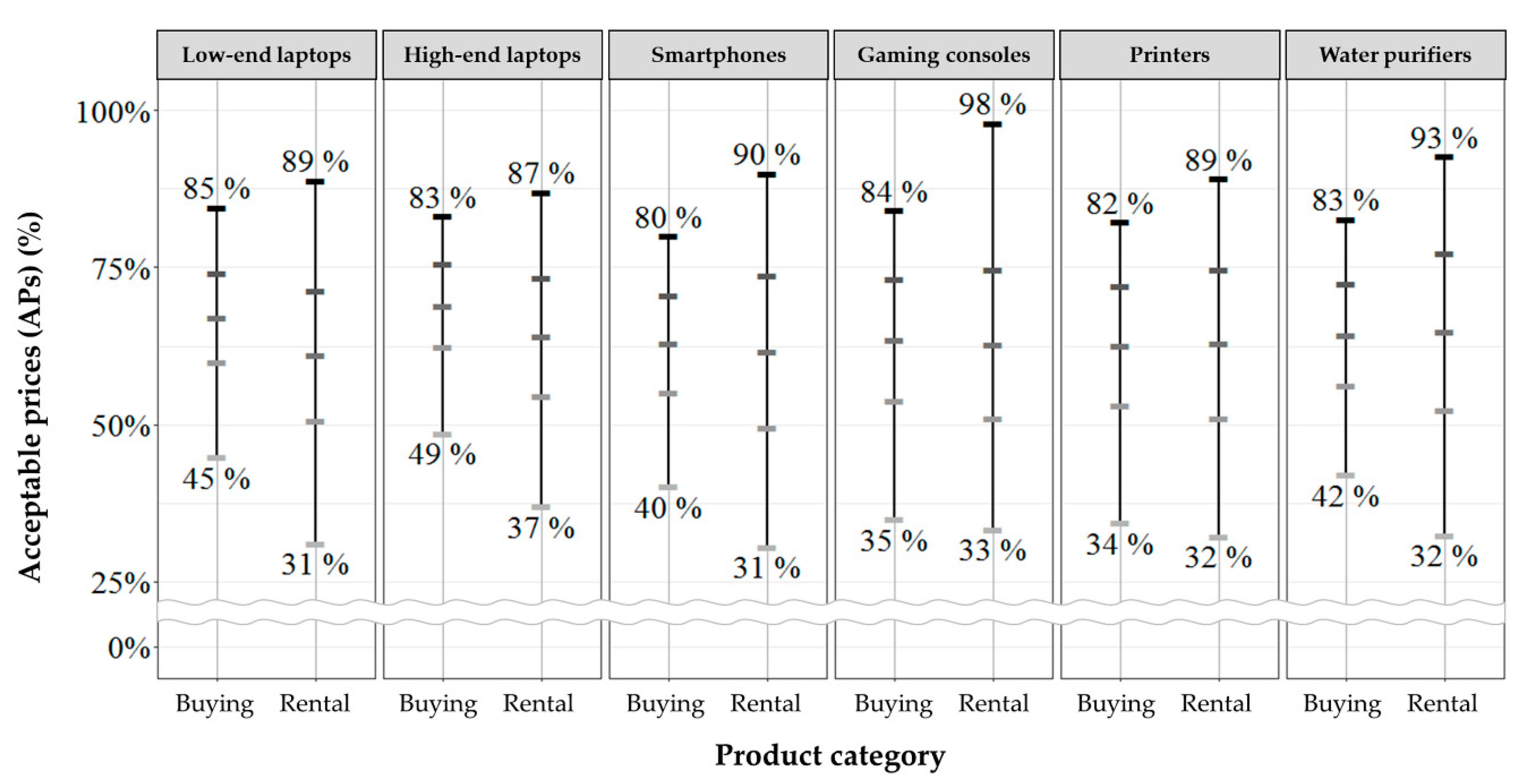

Although no difference was found among the product categories, differences in APs between the business models seem clear in all the product categories.

Figure 7 and

Table 16 compare the APs under the buying and the rental models. For each product category, the

t-test on each AP was conducted to determine whether there was a significant difference between the two business models. The

t-test results in

Table 16 show that the rental model affects the APs in two different ways: by decreasing the too cheap price and/or by increasing the too expensive price.

Decreased too cheap prices were observed in the low-end laptops, high-end laptops, smartphones, and water purifiers (Hypothesis H6a was partially supported.). This implies that the consumers doubt the quality of the remanufactured products less and thus, can accept lower prices than in the buying model. It seems that the rental model has a positive effect of reducing the quality concerns and reassuring the consumers. Increased too expensive prices appeared for the smartphones, gaming consoles, and printers. (Hypothesis H6e was partially supported.) It seems that the rental model makes the consumers feel the remanufactured products are more valuable and consider them as more comparable to the new ones. The rental model offers more customer care services making it more attractive and reducing the concerns for quality. Moreover, although the buying model requires a large initial cost, the rental model allows split payments, which is less burdensome. It seems that this makes the consumers become more generous when evaluating remanufactured products.

With the changes in APs, the APR increased in all the categories. The price range of each product category became wider under the rental model in

Figure 7. It can be interpreted that consumers are less sensitive and more generous to various price levels if they "rent" rather than "own" the remanufactured product. Such increased APR can be a positive sign for businesses, giving more freedom when developing a pricing strategy.

7. Discussion and Implications

Table 17 shows the hypotheses of the survey and the testing results. There are several implications of the results. First, the product categories make a difference in the relative value of remanufactured products. Specifically, NP and PI showed significant differences across the product categories under both buying and rental models. NP was 92–99% under the buying model and 74–91% under the rental model. PI was 49–84% under the buying model and 61–93% under the rental model. APs, however, showed a little difference only in the buying model; only the too cheap and the cheap prices of the buying model showed significant differences across the product categories. This indicates that consumers start doubting the product quality at different price points, specifically, at 34–49% of the new-product price. When remarketing remanufactured products, such differences of too cheap prices should be carefully considered, as lower prices do not necessarily lead to more sales. It was surprising that there was no noticeable difference in the too expensive price. The average too expensive price was 83% (buying) and 91% (rental) of the new-product price. Considering that the too expensive price represents the worth a consumer places on a product, it indicates that consumers think remanufactured products have 83% of the value (or 91% in rental) of the equivalent new products regardless of the product category.

Next, the effect of business models on the relative value of remanufactured products was supported. Switching the business model from buying to rental caused significant changes in NP, PI, and APs in almost all the product categories (H

2, H

4, and H

6 in

Table 17). Overall, changing to the rental model brought positive effects on NP and APs. NP decreased, meaning that more people considered a remanufactured product as an equivalent or a better option to the new one when they rent the product. The APs changed in two directions, either decreased at the too cheap price or increased at the too expensive price, leading to a wider APR. This implies that, under the rental model, people attributed more value to a remanufactured product and became less cautious about its quality.

Unlike NP and APs that showed common changes in all product categories, PI changed differently in each category. It increased for high-end laptops, gaming consoles, and water purifiers, however, decreased for low-end laptops and smartphones. It seems that product characteristics such as price level, reliability, and required consumables, and consumers’ personal characteristics such as income level, involvement, brand preference, and consciousness of others, affected the results. This means that changing to the rental model worked either positively or negatively depending on the category, and the suitability to the rental model varies across the product categories. The rental model can be a better option only for certain categories. Thus, if a remanufacturer should make a choice between the buying and the rental models, such difference by product category should be carefully taken into account. For instance, for the remanufactured low-end laptops and smartphones, companies should focus on the buying model rather than the rental model. For the other categories, the rental model can be a better choice. It should be noted, however, that offering both buying and rental models could be the best option for remanufacturers. It was shown that offering the rental model in addition to the buying model increased the total PI up to 27% in all the product categories (see

Table 12 for detail).

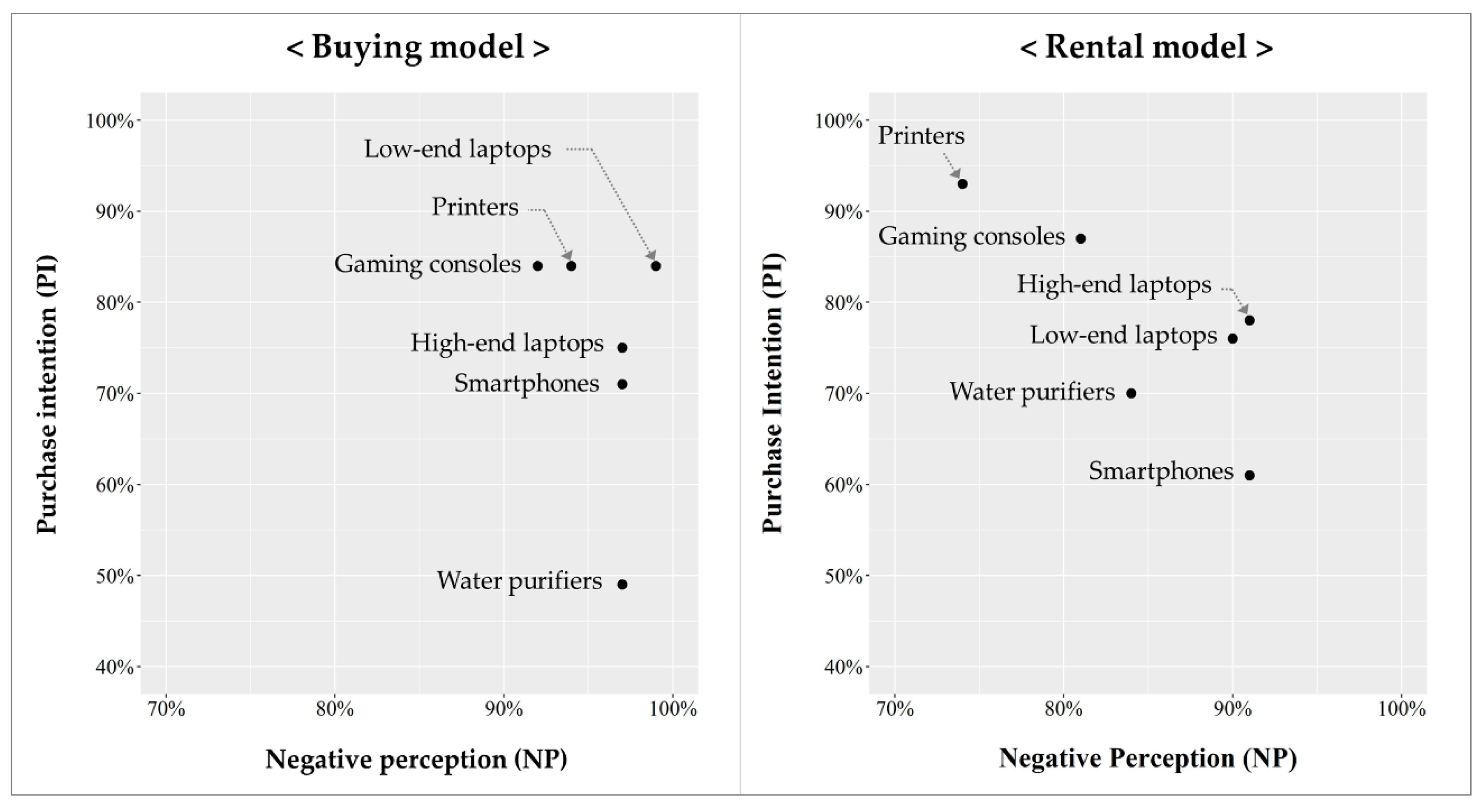

Figure 8 shows that several product categories are more suitable for the remanufacturing business from the consumer-demand perspective.

Figure 8 shows the NP (x-axis: the lower, the better) and the PI (y-axis: the higher, the better) of the six categories to compare their market potentials. The gaming consoles and printers showed greater market potential (lower NP and higher PI) under both buying and rental models. Although not shown in the figure, it is also notable that the two categories showed the lowest too cheap prices of 34% (printers) and 35% (gaming consoles) under the buying model. This implies that people are less concerned about the quality of remanufactured products. Low-end laptops are another category that seems to be suitable for remanufacturing under the buying model. The PI (84%) was among the highest under the buying model, although the NP was also the highest. This suggests that many people are willing to buy remanufactured low-end laptops if the price is reasonably cheaper than the new ones. However, consumers’ perception under the rental model is not so positive. The PI dropped to 76% for the remanufactured low-end laptops, and the rental model is not as recommendable as the buying model.

The water purifiers and the smartphones showed the least market potential, regardless of the business model. They showed the lowest PI in the buying and the rental model, respectively. Water purifiers are household appliances directly related to personal hygiene. It seems that the consumers cannot tolerate emotional discomfort regardless of its working condition and cleanliness. However, considering the increased PI (from 49% to 70%) and the declined NP (from 97% to 84%) when switching from the buying to the rental model, it is expected to be relatively more successful in the rental model. Therefore, if a water purifier is remanufactured, promoting rental services based on the hygienic image marketing seems recommendable. A smartphone is a personal device for everyday use, observed by others, and containing substantial personal information. It seems that such factors make the remanufactured smartphones undervalued, especially in the rental market. For remanufacturing smartphones, the traditional buying model would be more appropriate.

In summary, the current study demonstrates that both the product categories and business models cause significant differences in the relative value of remanufactured products. The survey results extend the findings of previous studies that have dealt with either a single product category or a single business model (refer to

Table 2 for detail). Especially, the results indicate that there are product categories that are naturally more advantageous for the remanufacturing businesses from a consumer-demand viewpoint. In addition, the results show that the rental model can be a lucrative option for the remanufacturing business for certain product categories. Considering the development of the sharing economy, these results can be beneficial for the remanufacturing industry. It is expected that a combination of remanufacturing and the rental model can contribute to saving more resources and for generating higher profit.

Highlighting the existence of a minimum acceptable (too cheap) price and its differences as per the product category is another important finding from this study. The results imply that a common assumption that a lower price leads to a higher quantity demanded may not hold for the remanufactured products. The results also indicate that the boundary price of the most significant differences among the categories is the minimum, and not the maximum. Such implications can be useful in establishing optimal pricing and remarketing strategies of the remanufactured products.

8. Conclusions

This study determines if and how the product category and business model affect consumer valuation and acceptance of remanufactured products. A survey was conducted to analyze the relative value of remanufactured products perceived by consumers (how valuable a remanufactured product is in comparison to the same-but-new version of the product). Six product categories (low-end laptops, high-end laptops, smartphones, gaming consoles, printers, and water purifiers) and two business models (buying and rental models) were selected as the factors. NP, PI, and APs were used as the measures of relative value.

As per the knowledge of the authors, this study took a novel approach that demonstrates the effect of product categories and business models on the value of remanufactured products. This study, however, has limitations as it surveyed a relatively small and homogeneous sample of university students and considered only six product categories. It highlights the potential impact of product categories and business models, but it may be difficult to generalize the results of this study to all consumers and all product categories. A possible gap between the stated survey answers and the actual purchase behavior is another limitation. Future research should involve a larger sample and should consider adopting data on actual purchase behavior. Different ways of data collection such as experiments, behavior observation, and web crawling can be considered.

In the future, it will be necessary to study the effect of consumers’ personal profiles on the value of remanufactured products. Personal profile characteristics, such as age, income level, education, prior knowledge/experiences, and level of involvement, are expected to have significant influences on consumer valuation. Linking characteristics of products and business models to consumer valuation is another area of research that is necessary and promising. The current study showed that consumer valuation for remanufactured products is different across the product categories and between the business models, which implies the significance and importance of product/business model characteristics. Clarifying the effect of the product/business model characteristics (such as initial cost, price gap between new and remanufactured products, reliability, design specifications, purpose and frequency purpose of use, relevance to hygiene, etc.) can provide useful implications for remanufacturing management and towards the design for remanufacturing. Ultimately, a consumer valuation model that incorporates both the consumer and the product/business model characteristics needs to be developed in the future. More advanced analysis techniques such as structural equation modeling, mathematical modeling and analysis, and data mining would provide a promising solution to this challenge.