Inner Archipelagos in Sicily. From Culture-Based Development to Creativity-Oriented Evolution

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Neoanthropocene Challenge: The General Theoretical Framework

1.2. The Post-Covid-19 Context: The Great Acceleration

2. Materials and Methods

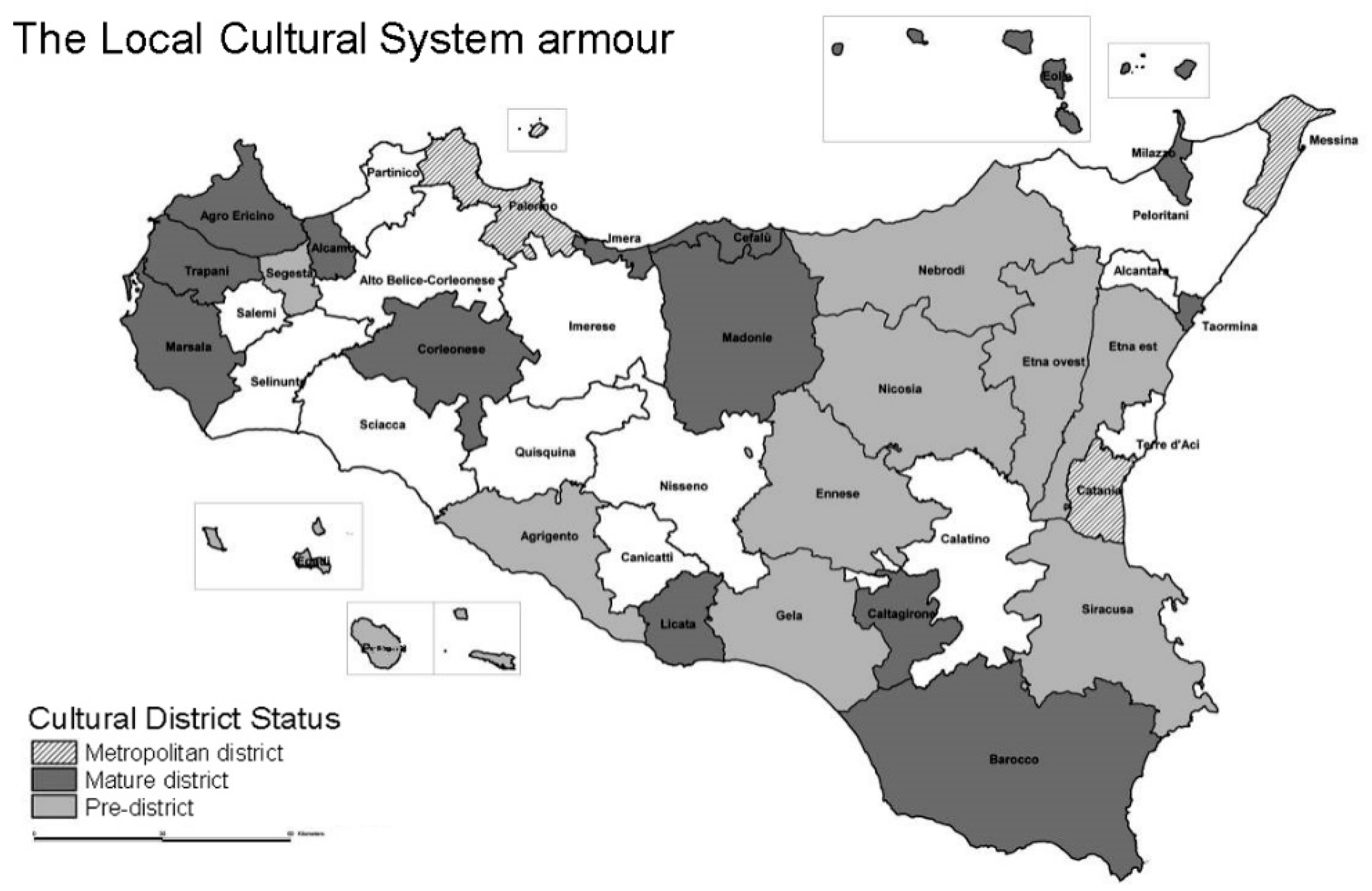

2.1. The Cultural Dimension of Development: The “Local Cultural Systems”

- New cultural policies must be implemented by urban communities, especially in medium-sized cities, in spreading the principles of sustainable development aimed at the adoption of local strategies, centered on the cultural identity.

- A stronger governance model of cultural heritage and activities must be checked and evaluated by an appropriate set of “cultural indicators” suitable for aiming at development that would be compatible in values and sustainable in resource use.

- Citizen engagement in culture-based development is a critical aspect. The social empowerment must be achieved as a key factor of local development towards forms of culture-based empowerment, promoting social cohesion, and gathering public support and ownership.

- The culture-based economic sectors must act as a “multiplier in the cultural domain”, with a mix of public funding and private investment geared to promoting and innovating cultural policies.

- Finally, the implementation must be conducted through the promotion of more strategies capable of integrating cultural development with social and economic development in such a way as to strengthen the quality of life.

- The historical identity that connotes its theme,

- the cultural belonging that connotes its relationships,

- the permanence that expresses its power, the proximity that shapes its space, and

- the exclusivity that shapes its boundaries.

2.2. Steps and Application of Methodological Framework in LCSs

- The concentration, distribution, and specificity of the cultural and natural heritage possessed is assessed on the cultural centrality index.

- The cultural specialization of municipalities is defined through the cultural flexibility index.

- The proximity and accessibility index has been assessed in relation to the transport infrastructure system and in relation to territorial “infostructures”, that is to say, the intangible network of digital communications, the thematic networks of exploitation and dissemination, the routes promoted, etc.;

- The size of economic activities in cultural domain, such as conservation and restoration of heritage, training and scientific research, enhancement, communication, tourism, and hotel activities.

- The cooperation index has been based on the opportunities offered by local projects (such as territorial pacts, natural archaeological and literary park policies, integrated territorial projects, and community initiative programs) related to cultural heritage or cultural production.

- The competitiveness index has been built starting by assessment of high-ranking services (e.g., university and postgraduate specialization) and the enhancement of territorial excellence (e.g., promotion of thematic itineraries, literary parks, etc.).

- The score for the hotel accommodation level: Starting from the reference score (x = n... beds/1000), different weightings have been assigned depending on the type and class of accommodation facilities (e.g., farmhouse = 2x).

- The score for state-owned equipped areas in the woods: 1 for presence, 0 for absence.

- The index of cultural heritage centrality (ICHC) has been calculated as ∑(Hc·100/h), in which Hc is the number of heritage sites for the recognized typologies and h the total of heritage sites. Each category is weighted by relevance.

- Index of the naturalistic heritage centrality (INHC) has been calculated as ∑(Pc·100/p), in which Pc is the number of natural parks and reserves for the recognized typologies and p the total of natural sites.

- Index of cultural services centrality (ICSC) has been calculated as ∑(Sc·100/s), in which Sc is the number of natural parks and reserves for the recognized typologies and s the total of natural sites.

- The score for municipal libraries: x = n whole volumes/100,000.

- The score related to the existence of rare book funds: x = n Volumes/1000.

- The score relative to the photo archives: x = n Volumes/1000.

- The score for wine itineraries: 1 for presence, 0 for absence.

- The score related to local culture-based projects.

- Maturity condition—the presence of territorial heritage and cultural services is such that it can already be considered sufficiently high and articulated, as well as related to the system of relationships and interdependencies in the context of local planning, training, and tourism.

- Trend condition—where the different component municipalities possess a fair level of heritage and services, and local projects of cultural specialization are detectable.

- Planning-in-progress condition—where the elements of the cultural heritage and services do not express a high degree of territorial specialization based on the cultural sector yet, and consequently the level of local culture-based development is low.

- Mature cultural district, that is in condition to start development policies based on the cultural dimension: It is the condition relative to local cultural systems characterized by the presence of a majority of municipalities in condition of “maturity” and a significant presence of municipalities in “trend” conditions.

- Pre-district, characterized by ample opportunities that await a project capable of putting them into effect: Condition relating to local cultural systems characterized by the presence of a majority of municipalities in “trend” condition.

- Proto-district, which needs a strong design action to transform the strengths of the cultural domain into opportunities for development: Condition relating to local cultural systems characterized by the presence of a majority of municipalities in “Planning-in-progress” condition.

- In-coming District, which has yet to complete the path of recognition of belonging to a system: Condition relating to local cultural systems characterized by the presence of a large majority of municipalities in “Planning-in-progress” condition of “planning”.

- Finally, the Metropolitan Cultural District has been introduced, in order to distinguish the characteristics and the opportunities of the three capital metropolitan cities of Catania, Messina, and Palermo, and of the district of the small islands and archipelagos to define the peculiar insular characteristics.

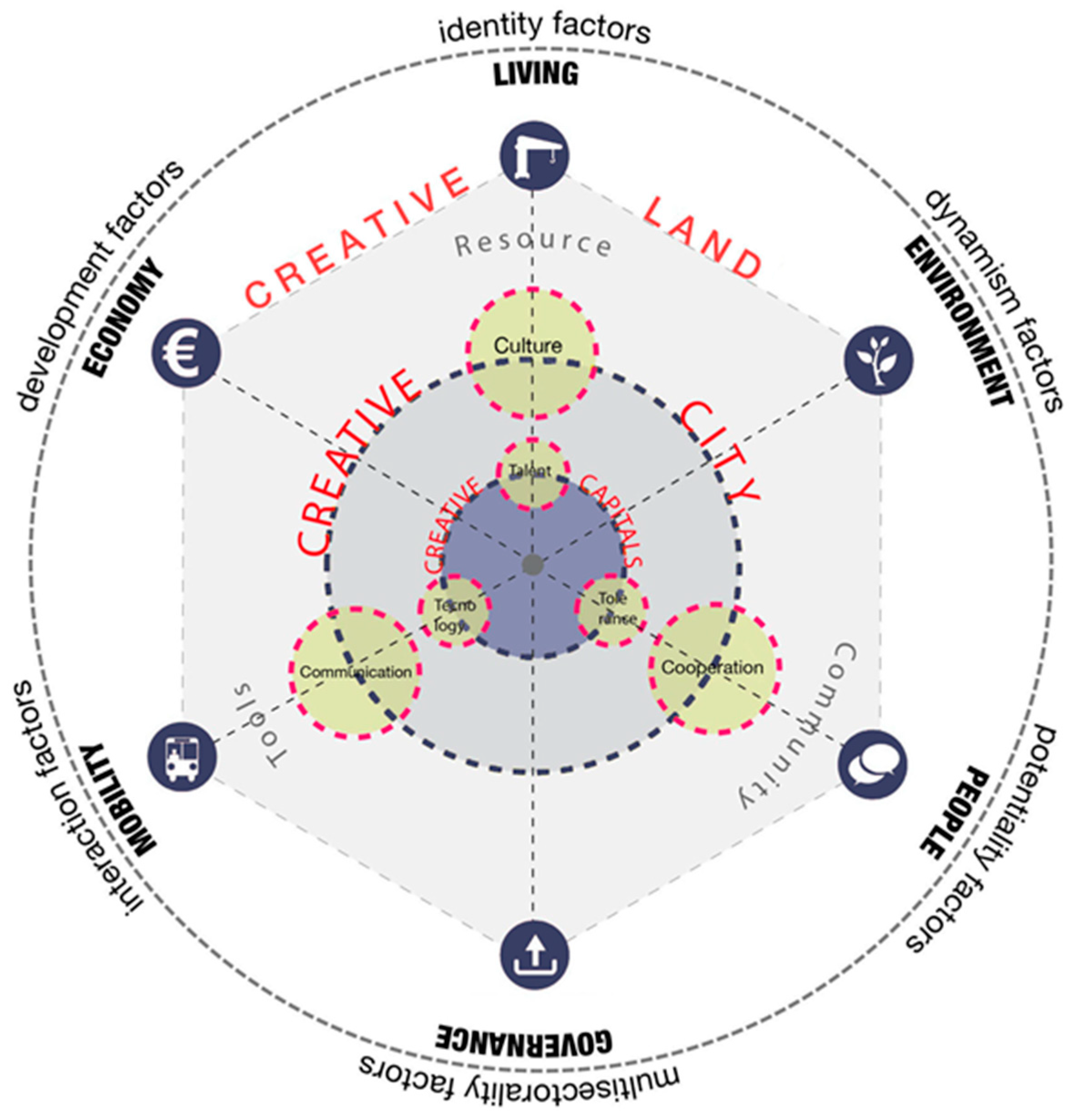

2.3. The Cultural Transition to the Neoanthropocene Age: From Culture-Based to Creativity-Based Local Development

- Competitiveness improvement policies based on cultural and natural resources and funded by regional and EU funds. The focus is on the increasing capacity of natural and archaeological parks as engines of development, including territories and municipalities that do not belong to the protected areas, but that are recognized as belonging to a territorial brand, such as Madonie Natural Park or Agrigento Archaeological Park. In this case, Park Authorities are the pivot to establish relations for drafting and implementation of development policies.

- Provincial development policies based on the specific competences of Provincial Administration, such as local infrastructures, tourism improvement, advertising campaign.

- Multilevel policies based on supralocal networks, combining the previous two policies.

- High level instruction and university policies, based on local resources such as the Research Centre in Bivona, on the Sicani mountains, for energy, environment, and local resources.

- The first is Culture, the territorial identity, steeped in history yet also extending into the future. Tangible and intangible culture is the most distinctive and competitive urban/rural resource, its identity and diversity as products of its history. Because the talent of a community could generate value, it must be submerged in the virtuous circle of the culture economy, the geography of experience, and the design of quality. Culture, therefore, plays a part in the field of resources, enabling cities to become more creative in the sustainable development sectors of living, economy, and environment.

- The second is Communication, namely an urban ability to inform, divulge information, and involve in real time its citizens and multitude of users, using all kind of technology and making possible interventions aimed at cutting down congestion and deterioration: A community which makes effective use of innovation technology is, indeed, also one which cuts down on travelling, keeps a check on pollution, and improves the way we work, delocalizing services and repositioning their centrality. Communication provides the setting of tools for development acceleration in the fields of economy, mobility, and governance. At last, it improves the ability of medium- and small-sized cities to be involved in global networks, even without a strong physical mobility network.

- And finally, the third factor is Cooperation, because, in global and multicultural cities, tolerance implies that the challenge faced by creative/generative land lies instead in the explicit collaboration among diversities, through cooperation among all users, between city centers and suburbs, between urban and rural functions. The creative land is not merely more open, multicultural, and multi-ethnic, but it must be capable of mobilizing its diverse component parts in the pursuit of a plan. Cooperation, therefore, redefines the community, assigning it new roles and clearer objectives for empowering smarter people relationships with governance and environment.

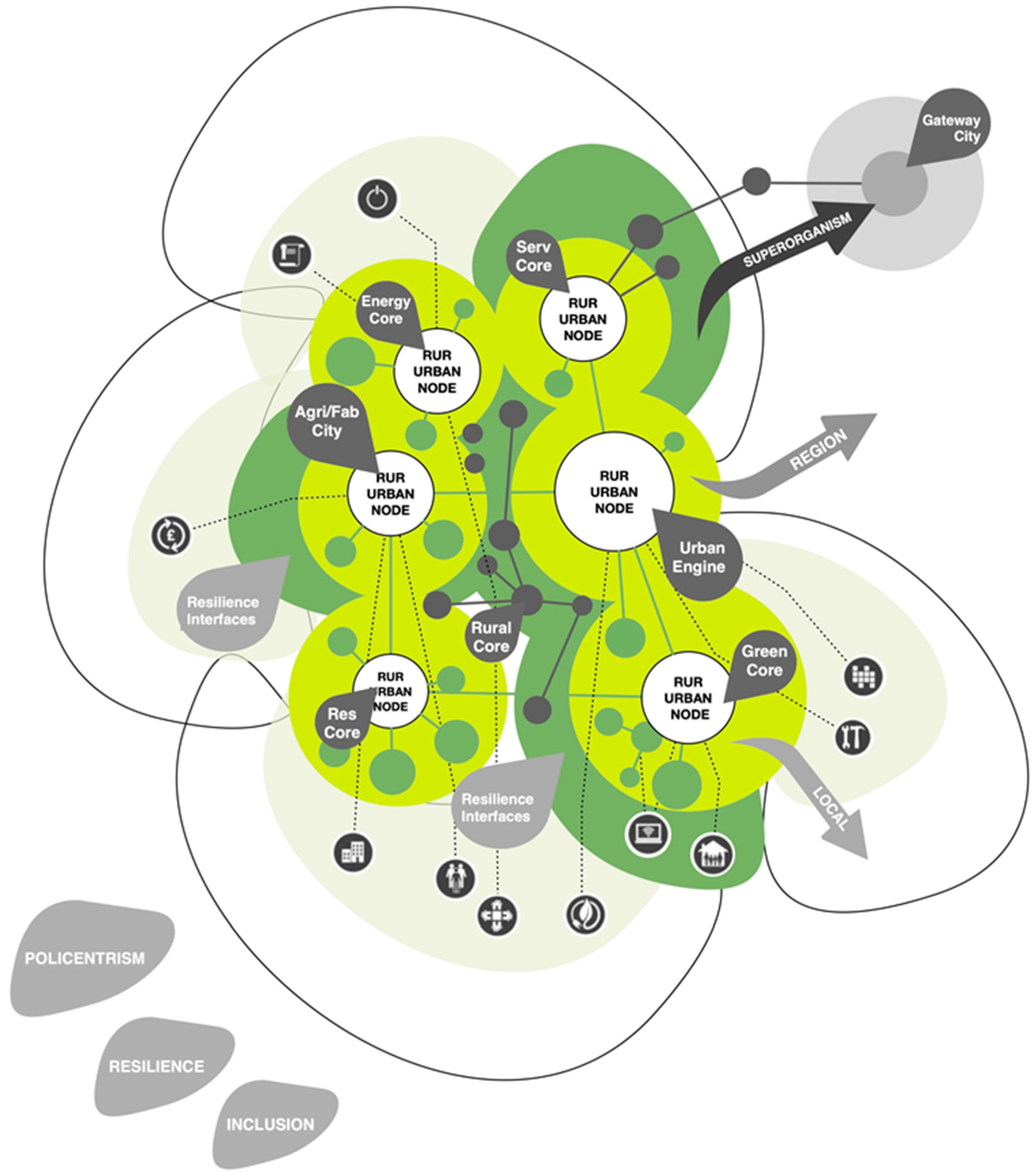

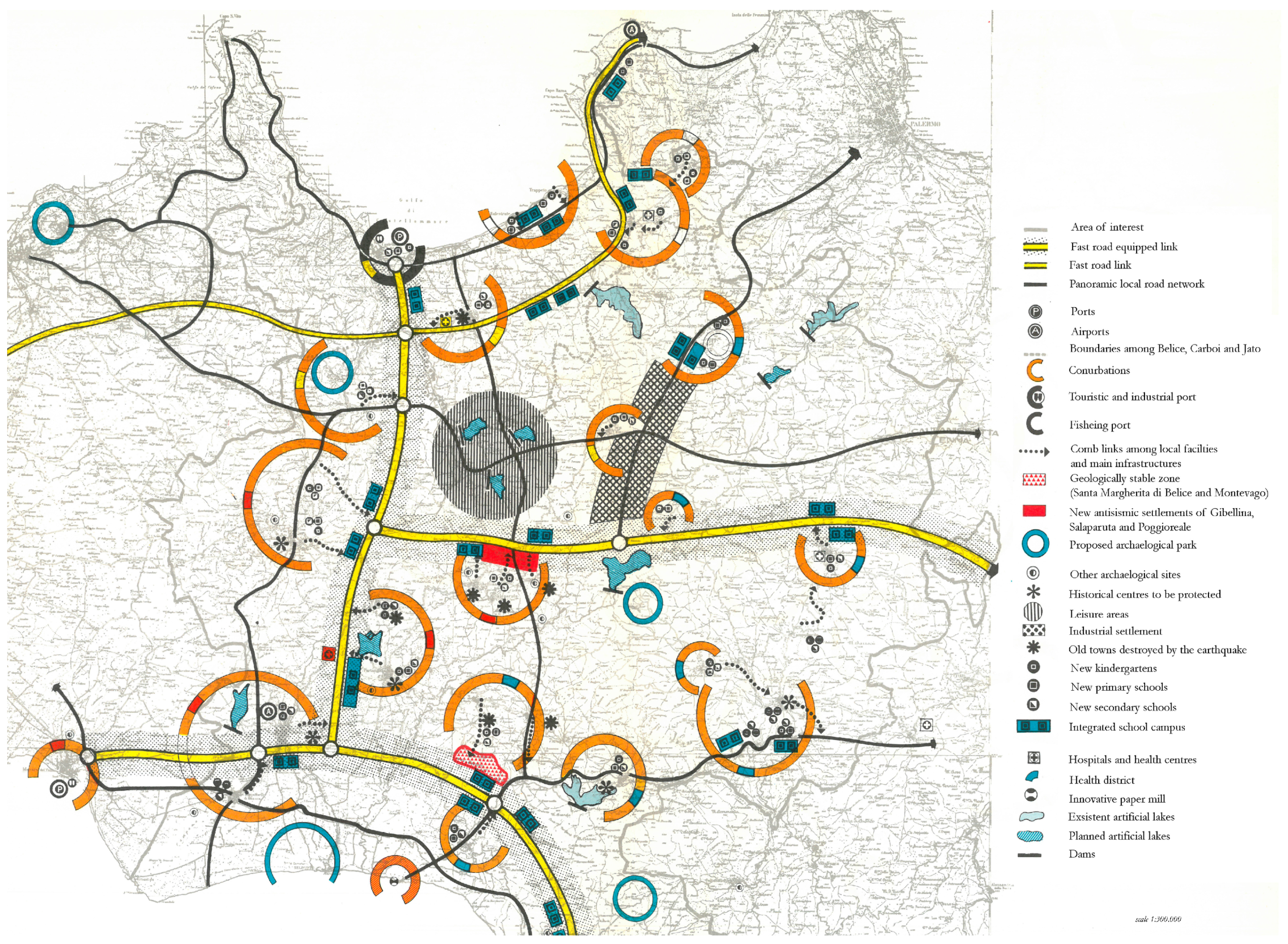

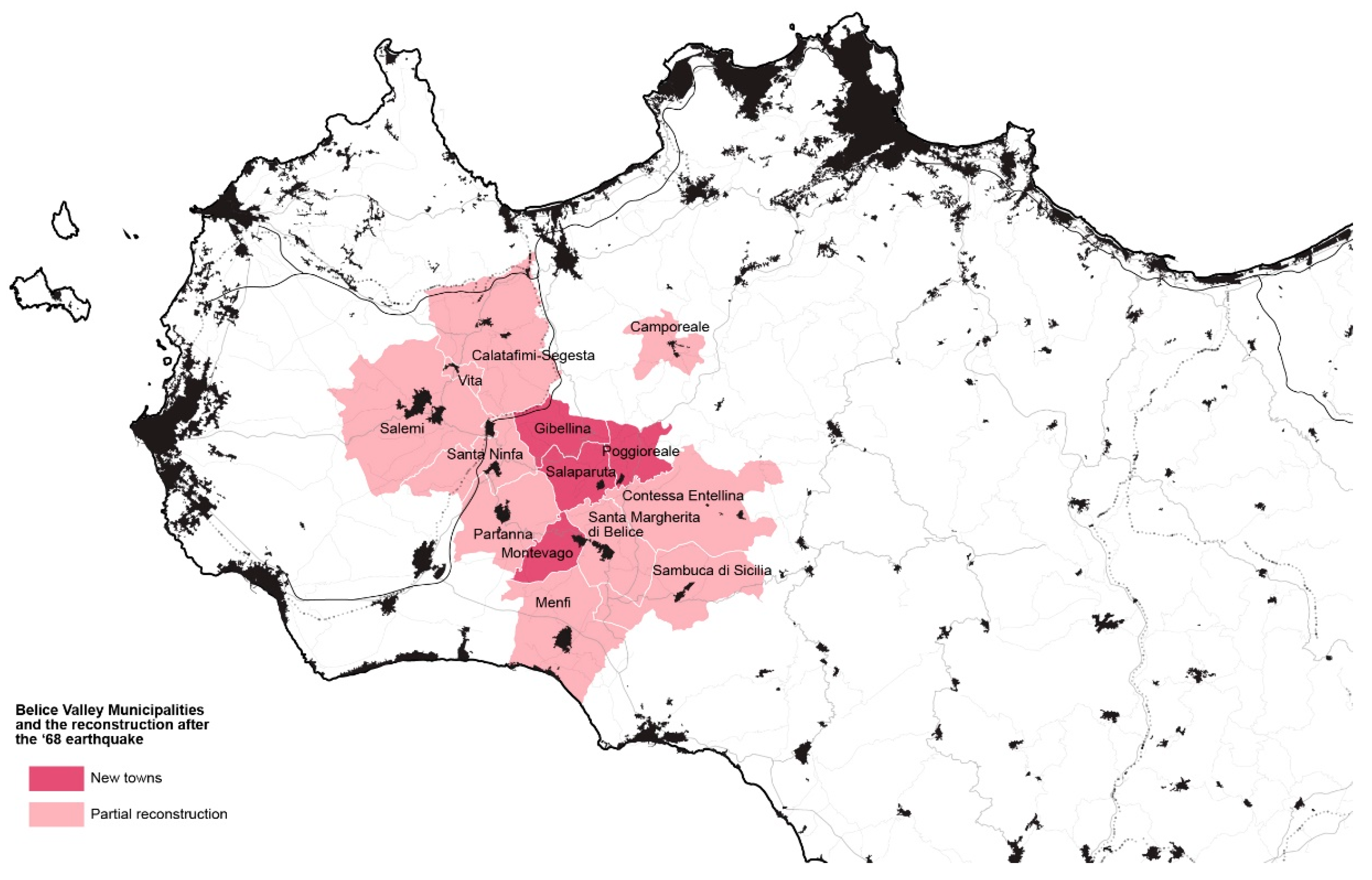

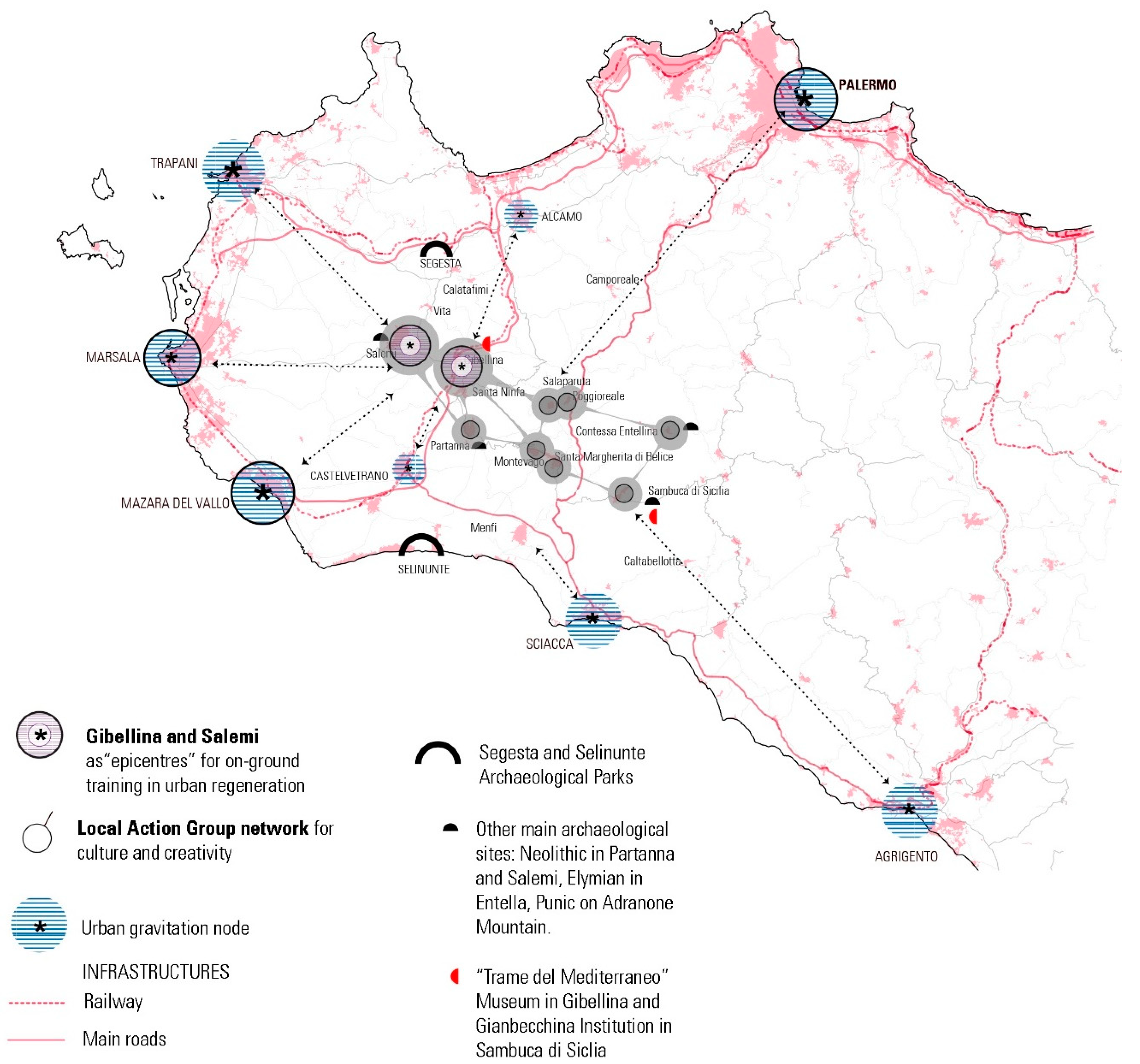

2.4. The Theory of Territorial Archipelago: Method and Applications in Belice Valley

2.5. Steps and Application of Methodological Framework in Belice Valley Archipelago

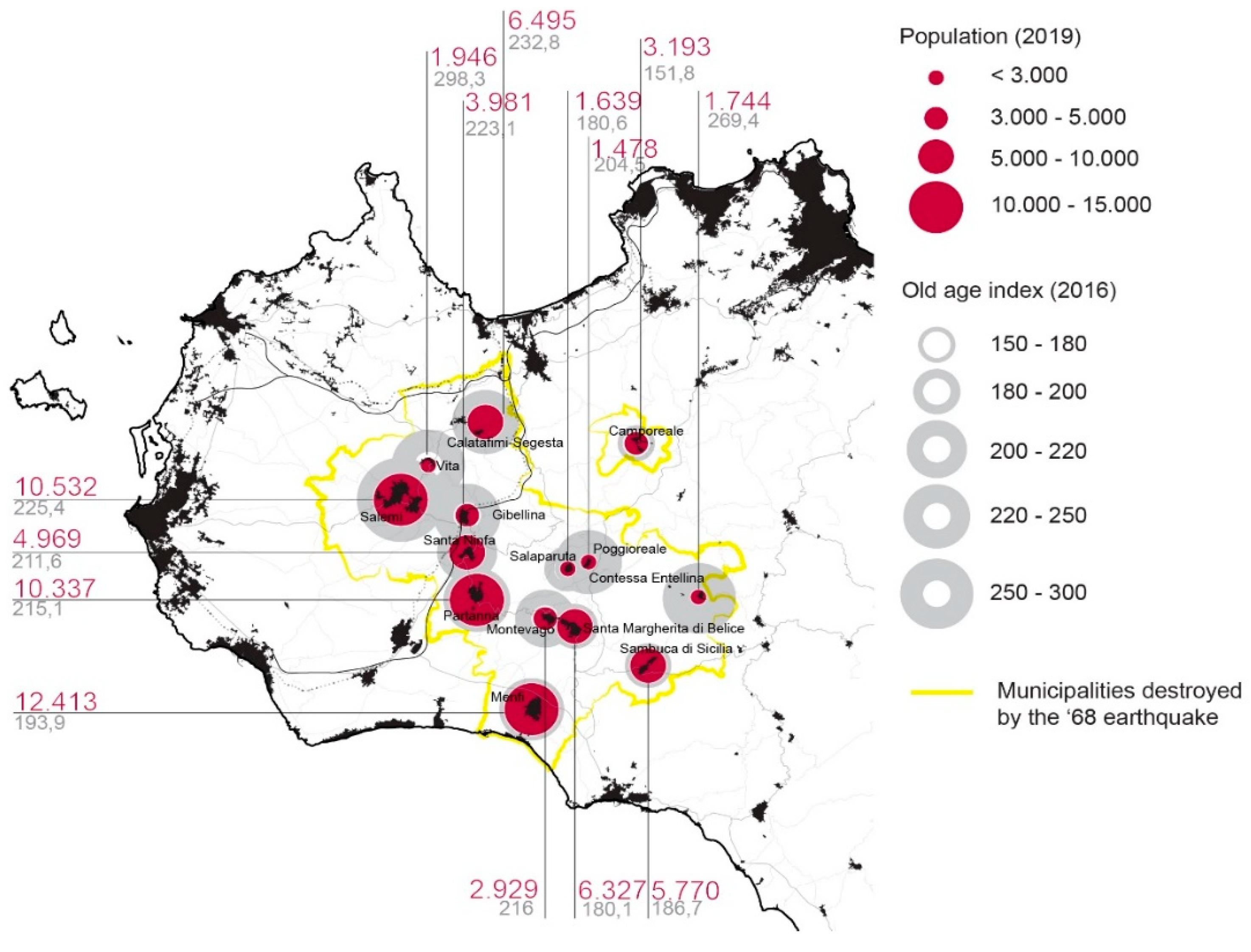

- Statistical maps are produced to define socio-economic background:

- ○

- Demographic analysis, as in Figure 6, concerning total population and old-age index. Between 1951 and 1971, the average percentage of depopulation was 18.2%. Between 1971 and 2001, the average percentage of depopulation was 9.6%. Between 2001 and 2019, the decrease process continued with a peak of 19.1% in Vita and of 13.91% in Camporeale. Today, in these territories the average value of the old age index highlights that younger people are constantly decreasing (the benchmark regional average is 1537).

- ○

- Unemployment rate. If we look at the unemployment rate 2004–2012 as the “percentage ratio between job seekers and the total labor force” referred to the Local Labour Systems, the ranking is between 14% and 23%.

- Relevance of each municipality is investigated through:

- ○

- Peripherical status, according to National Department for Development and Territorial Cohesion [36] in Belice Valley, there are “belt” (Salemi, Santa Ninfa, Partanna), “intermediate” (Calatafimi, Camporeale, Vita, Gibellina, Salaparuta, Poggioreale, Montevago, Menfi), and “peripherical” (Sambuca di Sicilia, Santa Margeherita di Belice, Contessa Entellina) municipalities with weak connections to the nearest metropolitan cities and facilities.

- ○

- Map of cross-check with the Local Cultural Systems. The map checks in what way the regional policies can support the structure of a territorial archipelago. The LCS boundaries and the archipelago do not necessarily overlap one on another.

- ○

- Locations of high schools. High school offer is linked to technical-commercial training in Partanna, Menfi, and Salemi, and professional training for tourism and commercial activities in Menfi and Santa Ninfa. There are, however, also five high schools mainly linked to social disciplines.

- ○

- Local partnership capacity and local coalition map. The map describes how many municipalities are engaged with the Local Action Group funded by Leader+ program. It is relevant in terms of capacity building and opportunity in future development.

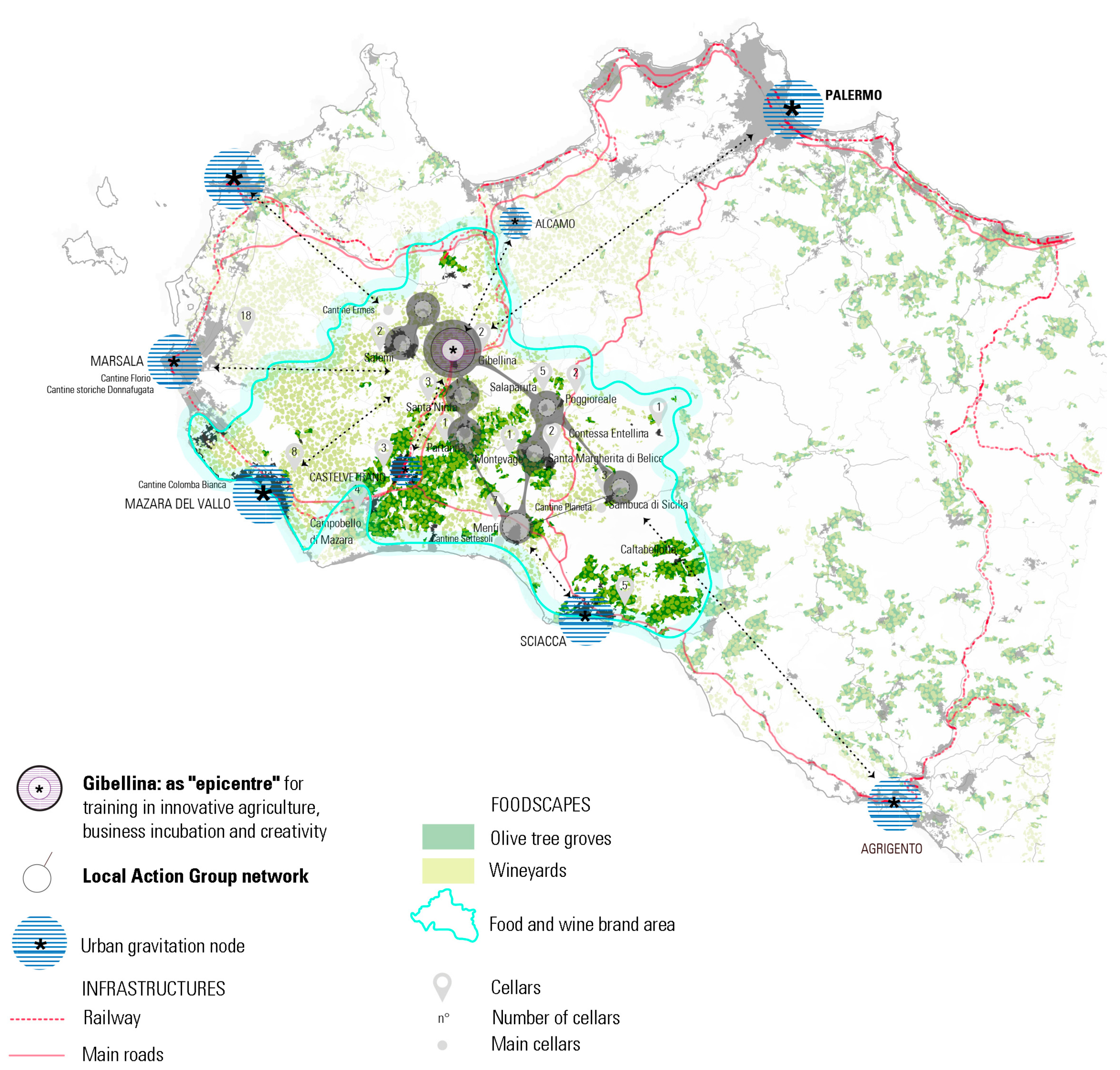

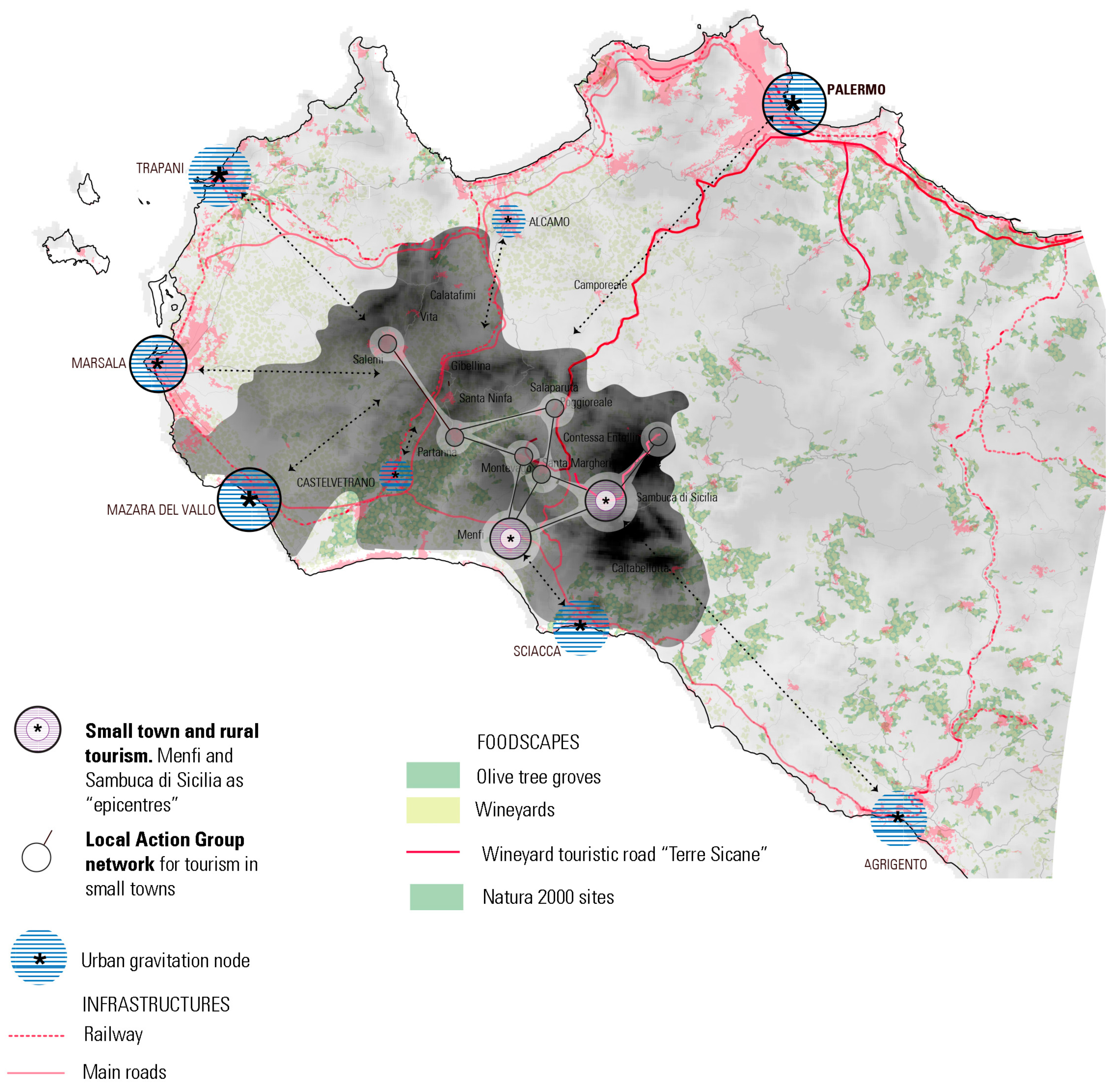

- Local assets in rur-urban context are recognized and mapped, as an in-depth analysis of strengths on which the research group has built the vision:

- ○

- Map of abandoned buildings and areas. Many lifecycles were cut by the earthquake effects and abandoned quarries, mines, disused railways, toll booths, obsolete infrastructure, and derelict productive settlements are elements that have gone through territorial transformations while maintaining their shape (entirely or partially) but losing functional and relational aspects.

- ○

- Map of agricultural production and utilized agricultural areas (UAA) statistical analysis. This map is based on CORINE land cover and supports the analysis on utilized agricultural areas as statistically defined by National Agriculture Census. A strong reduction in UAA is evident in Belice, but on the contrary we can recognize a large mechanization and specialization in olive tree production and vineyards more than in the previous decades.

- ○

- Map of quality brands in food and wine sector. This map describes the consistency of food and wine brands and certifications, such as the Italian Protected and Controlled Designation of Origin or Typical Geographic Indication. It is needed to qualify the economic potential in the agricultural sector.

- ○

- Map of main wine cellars. This map is cross-referred to the previous two maps and it assesses the wine production. It is based on local commercial and business registers.

- ○

- Map of the food and wine routes. This map contributes to complete the wine economy framework with wine tourism activities. It is based on a regional touristic database.

- ○

- Map of contemporary architecture and new towns. A peculiar thematic is the count of new towns, buildings, and public spaces made after 1968. It is based on direct survey and cross-check in national, regional, and municipal archives [27].

- Cultural identity framework is completed with the collection of imagery and bio-profiles of local personalities who played a significant role in recent local events:

- ○

- Collection of historical images and maps. It is needed to detail and confirm the historical evolution of towns and territory, and to do a quality assessment of the lost social structure.

- ○

- Recognition of beacon personalities in recent local history and in the present. In Belice Valley, this work—often based on direct survey—contributes to set up the community identity.

- A map that describes a cluster of towns and territories that have the resources and opportunities to implement the strategy.

- Some models of application designed as examples, as suggestions for further design.

- Some engaged user simulations to check in what way it is possible to attract new abroad users.

3. Results: Creativity for Sustainable Development

4. Discussion

4.1. The Belice Archipelago as Living Lab for a Post-COVID-19 Creative Land

4.2. A Cultural Transition Agenda in Belice Valley

- Creative Labs: Integrated urban regeneration programs based on the development and consolidation of creative districts as living labs and incubators of ideas, culture, production, and social development within which integrate and enhance public demand and decision-making, talents, resources’ consumption reduction, energy efficiency, and incentives with the opportunities for private entrepreneurship.

- Covenant of creativity: Drawing up of creative regeneration agreements or action plans formulated in highly participative ways in support of environmental and social sustainability, accompanied by monitoring benchmarks based on parameters related to the metabolism of buildings and public spaces, mobility, the waste cycle, and the digital infrastructure. The value of culture and creativity for generating income and jobs has been largely proven. What should be measured first now is what is the cost of not valuing culture and creativity in urban planning.

- Creative capacity building: Activation of project-oriented, economic-driven, and management-based local agencies or steering committees to enhance the creative cooperation at the city level contributing to foster the development of public-private-civil society partnerships and to attract investments, connected to a responsible simplification and to a greater effectiveness of the administration in the field of culture and creativity policies.

- Convergence and cross protocols: Developing positive convergences between the different creative sectors, but also between them and the other sectors of the economy following integrated and transversal approaches and operative protocols based on exploration, co-creation, experimentation, and evaluation. Creative urban policies must encourage spill-overs and spin-offs and cross discipline collaboration.

- Creative dividend: Designing innovative tools for the creative city governance through the promotion of new culture-based frameworks for spreading the creativity’s impact in everyday life. The creative dividend, through the six factors drawn in the external circle of the Figure 2. (identity, dynamism, potentiality, multisectorality, interaction, and development), acts on quality of life and spatial equalization, on environmental active protection, on people empowerment and social innovation, on multilevel governance and management incentives, on sustainable mobility, and on taxes and fiscal leverage. The structural interaction of six factors of creative dividend can enhance the social return on investment in culture and creativity and the spread of positive effects and effective impacts. The ethical dimension of culture and creativity needs a creativity dividend as an active instrument to improve the values’ generation for reduce inequality and differences. We are moving from the creative economy to creativity in the economy as creativity is a catalyst leading to new business models in every sector, building notably in the opportunities offered by the alliance between digital technologies and social innovation.

5. Conclusions

- Rethinking the places of living from a centripetal model towards more distributed (but without soil consumption) hybrid and flexible forms that allow the settlement of different life cycles with variable intensity.

- Redesigning, modernizing, and making healthy large-area services for the inhabitants of the archipelagos, often temporary, who continually redefine human and spatial relationships.

- Reinforcing the systemic cooperation of services for social inclusion and for the new welfare, especially with reference to the smaller towns, which in the polycentric perspective, will be the new connecting hinge areas of the wider territories, through the localization of the new cultural ecosystem.

- Redefining the relationships between metropolitan cities and archipelagos in collaborative forms in attracting the most suitable segments of the production chains by redistributing them along the networks of local development, also according to a principle of greater resilience to crises.

- Finally, redefining the governance processes and tools for large area policies, according to an effective enabling subsidiarity of the new local cultural ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morin, E. Sur la Crise: Pour une Crisologie Suivi de Où Va le Monde? Flammarion: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Neiderud, C.-J. How urbanization affects the epidemiology of emerging infectious diseases. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2015, 5, 27060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2007: A Safer Future. Global Public Health Security in the 21st Century; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzari, M. Pandemia Covid19, resilienza e rischio sostenibile: Nuove regole di convivenza tra natura e uomo nell’Antropocene. In Impareremo il Futuro Tra Ucronie e Utopie. Il Virus del 2020; Pellettieri, A., Ed.; Zaccara Editore: Lagonegro, Italy, 2020; pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The Limits to Growth; Potomac Associates—Universe Books: Falls Church, VA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health in All Policies: Helsinki Statement. Framework for Country Action; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Reshaping Cultural Policies: A Decade Promoting the Diversity of Cultural Expressions for Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, P.J.; Stoermer, E.F. The Anthropocene. IGBP Int. Geosph. Biosph. Program. Newsl. 2000. Available online: http://www.igbp.net/download/18.316f18321323470177580001401/1376383088452/NL41.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Crutzen, P.J. Benvenuti Nell’antropocene. L’uomo ha Cambiato il Clima, la Terra Entra in una Nuova Era; Mondadori: Milan, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe European Landscape Convention. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/176 (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Cucinella, M. Arcipelago Italia. Progetti per il Futuro dei Territori Interni del Paese. Padiglione Italia alla Biennale Architettura 2018; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carta, M. Planning for the Rur-Urban Anthropocene. In Territories. Rural-Urban Strategies; Schroeder, J., Carta, M., Ferretti, M., Lino, B., Eds.; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carta, M. Futuro. Politiche per un Diverso Presente; Rubbettino: Soveria Mannelli, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, R.; Pratt, A.C.; Virani, T.E. Creative Hubs in Question. Place, Space and Work in the Creative Economy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carta, M.; Lino, B.; Orlando, M. Innovazione sociale e creatività. Nuovi scenari di sviluppo per il territorio sicano. Arch. Stud. Urb. Reg. 2018, 49, 140–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, M. Pianificare nel Dominio Culturale. Indicatori e Strategie per la Formazione di Distretti Culturali in Sicilia; Dipartimento Città e Territorio Press: Palermo, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Claxton, M. Culture and Development: A Study; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford Univerity Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Européenne. SDEC—Schéma de Développement de l’Espace Communautaire Vers un Développement Spatial Équilibré et Durable du Territoire de l’Union Européenne. Office des Publications Officielles des Communautés Européennes. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/pdf/sum_fr.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Carta, M. L’armatura Culturale del Territorio: Il Patrimonio Culturale Come Matrice di Identità e Strumento di Sviluppo; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi, A. (Ed.) Il Territorio Dell’abitare; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vinci, I. Pianificazione Strategica in Contesti Fragili; Alinea: Florence, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero delle Infrastrutture e dei Trasporti. Reti e Territori al Futuro. Materiali per una Visione; Ministero delle Infrastrutture e dei Trasporti: Rome, Italy, 2007.

- Carta, M.; Ronsivalle, D. Territori Interni. La Pianificazione Integrata per lo Sviluppo Circolare: Metodologie, Approcci, Applicazioni per Nuovi Cicli di Vita; Aracne Internazionale: Ariccia, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carta, M.; Contato, A.; Orlando, M. (Eds.) Pianificare L’innovazione Locale: Strategie e Progetti per lo Sviluppo Locale Creativo: L’esperienza del SicaniLab; Franco Angeli Edizioni: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lino, B.; Oliva, J.S.; Carta, M. Favara Futures: Research Workshop. In Dynamics of Periphery. Atlas for Emerging Creative Resilient Habitats; Schroeder, J., Carta, M., Ferretti, M., Lino, B., Eds.; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Badami, A. Gibellina, la Città che Visse Due Volte: Terremoto e Ricostruzione Nella Valle del Belice; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The UK Government. Department for Digital Culture Media & Sport Creative Industries Mapping Documents. Demonstrating the Success of Our Creative Industries. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/creative-industries-mapping-documents-2001 (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Ottone, R.E. Creative Cities Programme for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carta, M. The Augmented City. A Paradigm Shift; List Lab: Trento, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, E. La Nuova Geografia del Lavoro; Mondadori: Milan, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rodin, J. The Resilience Dividend: Being Strong in a World Where Things Go Wrong; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dolci, D. Inventare il Futuro; Laterza: Bari, Italy, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Carta, G. Il piano di sviluppo urbanistico delle valli del Belice, del Carboi e dello Jato. Urbanistica 1970, 56, 66–90. [Google Scholar]

- Accordo di Partenariato 2014–2020. Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne: Definizione, Obiettivi, Strumenti e Governance. Available online: https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/890263/strategia_nazionale_aree_interne.pdf/d10fc111-65c0-4acd-b253-63efae626b19 (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Garcia, E. How to Mitigate the Impact of an Epidemic and Prevent the Spread of the Next Viral Disease: A Guide for Designers. 2020. Available online: https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/2020/03/how-to-mitigate-the-impact-of-an-epidemic-and-prevent-the-spread-of-viral-diseases-a-guide-for-designers/ (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- World Tourism Organization. Supporting Jobs and Economies through Travel and Tourism—A Call for Action to Mitigate the Socio-Economic Impact of COVID-19 and Accelerate Recovery; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Town | Population (2019) | Δ of Depopulation 2001–2019 (%) | Old-Age Index (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calatafimi-Segesta | 6495 | –13.29 | 232.8 |

| Contessa Entellina | 1744 | –11.92 | 269.4 |

| Camporeale | 3193 | –13.91 | 151.8 |

| Gibellina | 3981 | –14.81 | 223.1 |

| Menfi | 12,413 | –2.89 | 193.9 |

| Montevago | 2929 | –5.46 | 216 |

| Partanna | 10,337 | –9.06 | 215.1 |

| Poggioreale | 1478 | –13.77 | 239.6 |

| Salaparuta | 1639 | –10.44 | 180.6 |

| Salemi | 10,532 | –8.96 | 225.4 |

| Sambuca di Sicilia | 5770 | –6.26 | 186.7 |

| Santa Margherita di Belice | 6327 | –3.64 | 180.1 |

| Santa Ninfa | 4969 | –2.47 | 211.6 |

| Vita | 1946 | –19.81 | 298.3 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carta, M.; Ronsivalle, D.; Lino, B. Inner Archipelagos in Sicily. From Culture-Based Development to Creativity-Oriented Evolution. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187452

Carta M, Ronsivalle D, Lino B. Inner Archipelagos in Sicily. From Culture-Based Development to Creativity-Oriented Evolution. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187452

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarta, Maurizio, Daniele Ronsivalle, and Barbara Lino. 2020. "Inner Archipelagos in Sicily. From Culture-Based Development to Creativity-Oriented Evolution" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187452

APA StyleCarta, M., Ronsivalle, D., & Lino, B. (2020). Inner Archipelagos in Sicily. From Culture-Based Development to Creativity-Oriented Evolution. Sustainability, 12(18), 7452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187452