Management Financial Incentives and Firm Performance in a Sustainable Development Framework: Empirical Evidence from European Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Board Compensation and Remunerations as a Relevant Mechanism of Corporate Governance

2.2. The Relationship between Board Compensation, Corporate Sustainability and Company Performances

- the institutional discrepancies between countries partially explain the inconclusive results for the linkage between corporate governance and performance and, at the same time, “raise concern about whether the principles of corporate governance which originated from developed countries are applicable in other countries” [8] (p. 249).

3. Research Hypotheses, Data and Methodology

3.1. Research Hypotheses

3.2. Data and Indicators

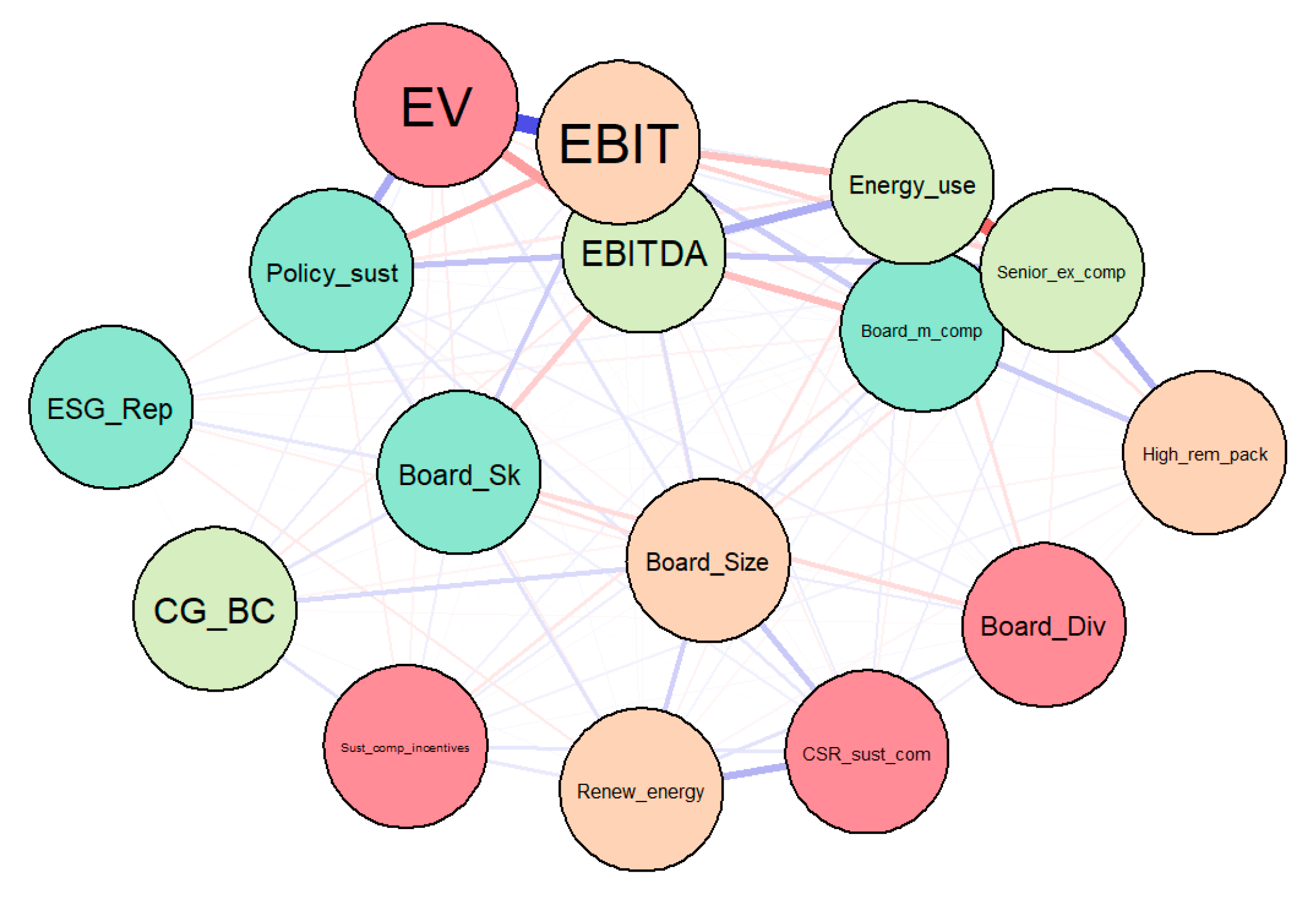

- firm performance indicators: Enterprise value—EV (mean, next fiscal year—FY1, United States Dollar—USD), Earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization—EBITDA (mean FY1, USD), Earnings before interest and taxes—EBIT (mean, FY1, USD);

- firm size: Total assets—Assets (mean, FY1, USD);

- management financial incentives: total board member compensation—Board_m_comp (prior fiscal year—FY0, USD), total senior executives’ compensation—Senior_ex_comp (FY0, USD), highest remuneration package—High_rem_pack (FY0, USD);

- corporate governance and board characteristics: corporate governance board committee—CG_BC (FY0, binary, yes = 1, no = 0), board size—Board_Size (FY0, number), board background and skills—Board_Sk (FY0, binary, yes = 1, no = 0), board gender diversity—Board_Div (percent, FY0);

- sustainable development credentials: Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) reporting scope—ESG_rep (FY0, percent), Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), sustainability committee—CSR_sust_com (FY0, binary, yes = 1, no = 0), Energy use total—Energy_use (FY0), Renewable energy use—Renew_energy (FY0, binary, yes = 1, no = 0), Policy sustainable packaging—Policy_sust (FY0, binary, yes = 1, no = 0), Sustainability compensation incentives—Sust_comp_incent (FY0, binary, yes = 1, no = 0).

3.3. Methodology

- MFI—Management Financial Incentives indicators (Board_m_comp, Senior_ex_comp, High_rem_pack);

- SDD—Sustainable Development Dimensions indicators (Sust_comp_incent, Policy_sust, Energy_use, Renewable_energy, CSR_sust_com, ESG_rep);

- CGBC—Corporate Governance and Board Characteristics indicators (CG_BC, Board_Size, Board_div, Board_Sk);

- δ and β—parameters that need to be estimated;

- ε—stochastic element;

- and —variables accounting for spatial and time effects.

4. Results and Discussion

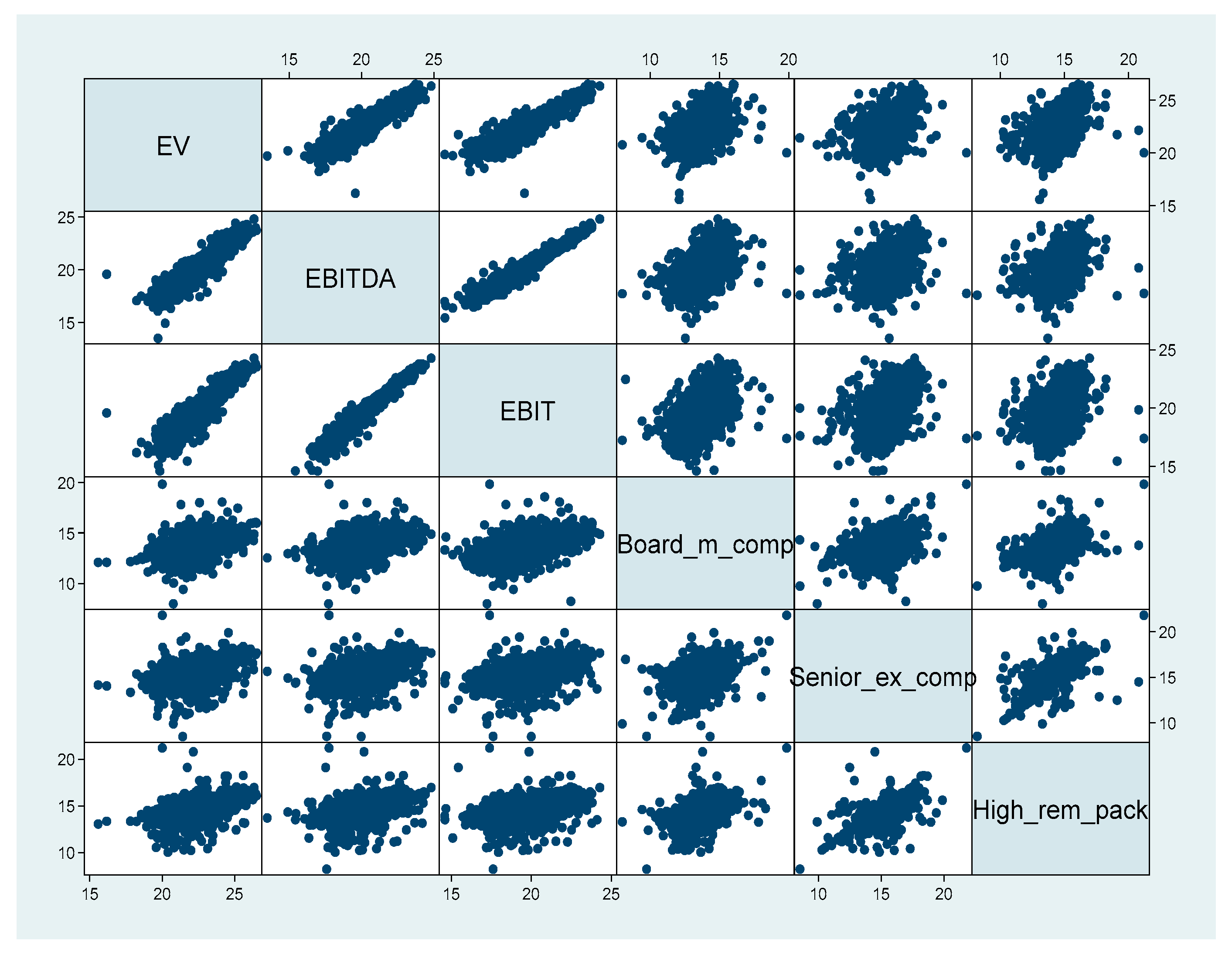

4.1. Results of Econometric Models (Robust Regression)

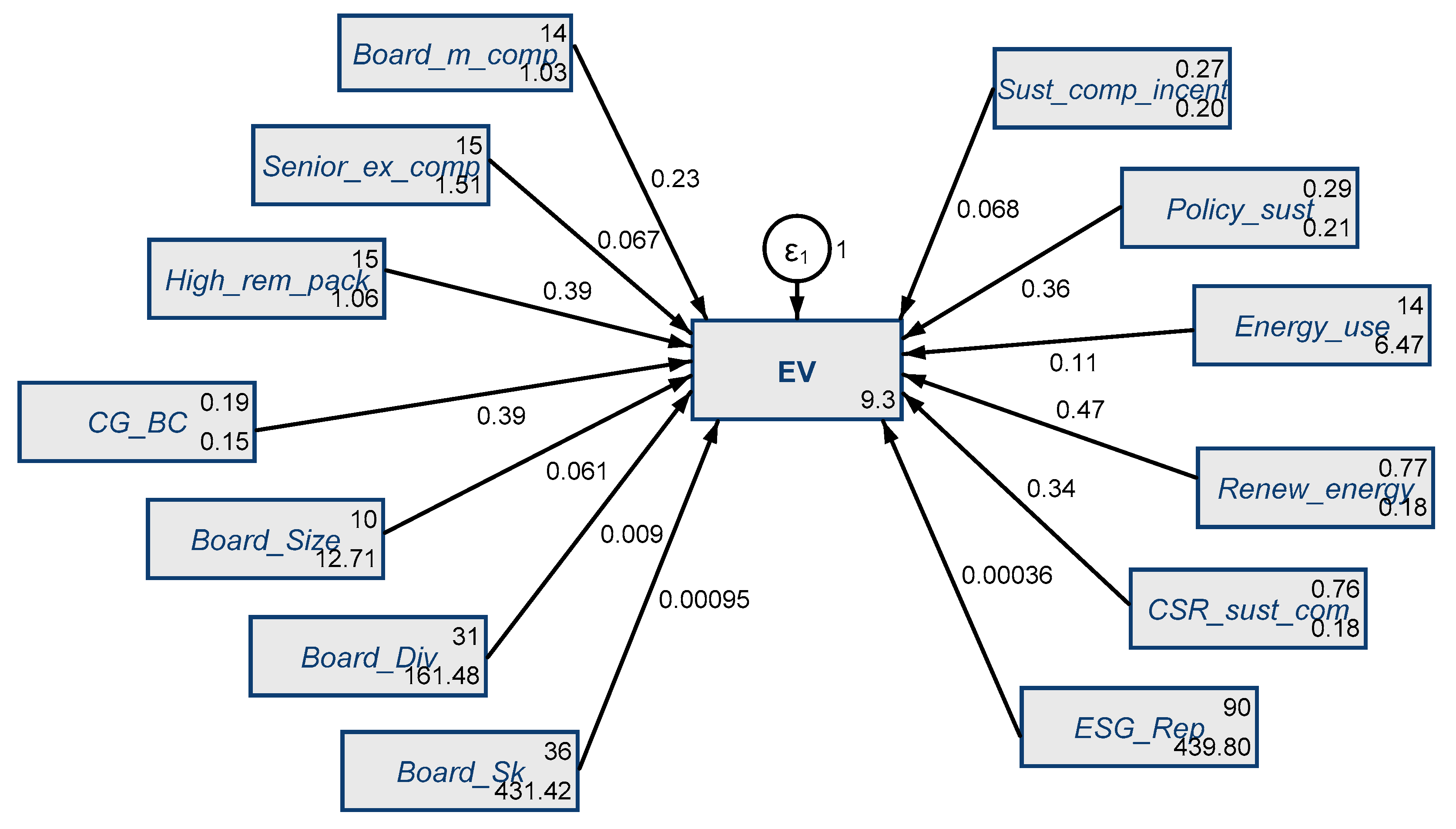

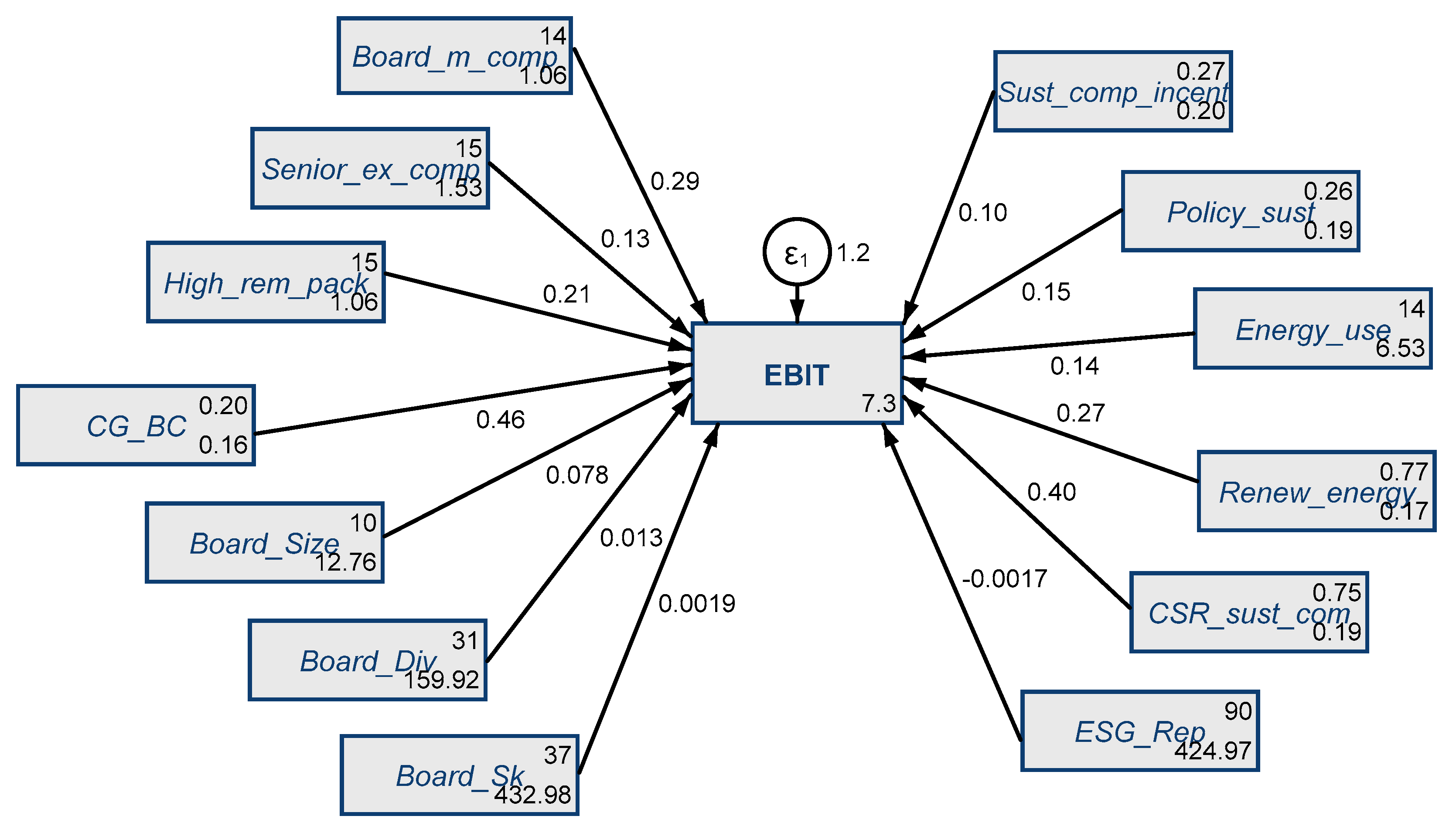

4.2. Results of Structural Equation Models (SEMs)

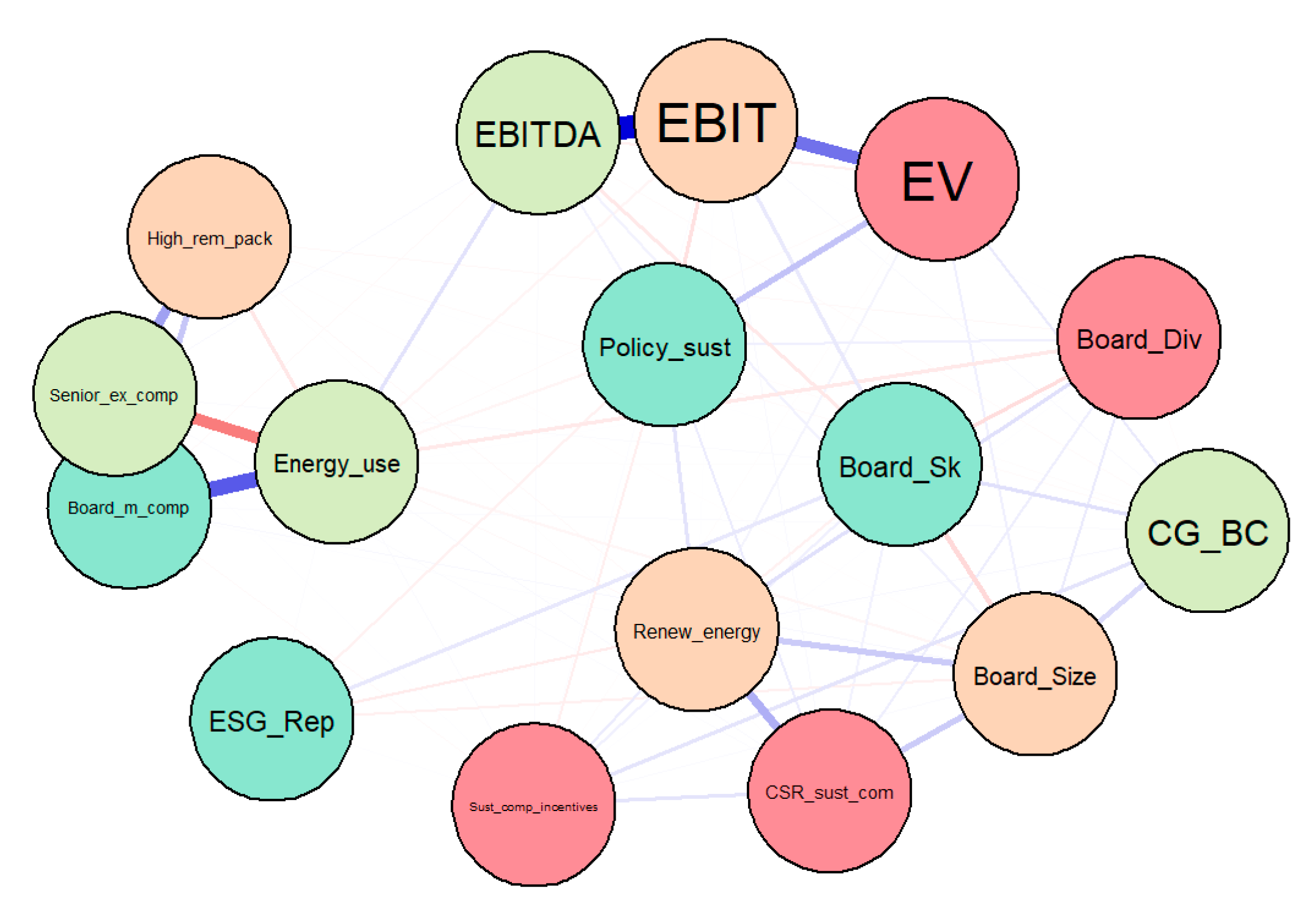

4.3. Results of the Network Analysis—Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EV | 1229 | 1.30 × 1010 | 3.06 × 1010 | −2.03 × 1010 | 3.25 × 1011 |

| EBITDA | 1371 | 1.42 × 109 | 3.92 × 109 | −4.62 × 108 | 5.97 × 1010 |

| EBIT | 1482 | 1.04 × 109 | 2.69 × 109 | −5.95 × 108 | 3.49 × 1010 |

| Board_m_comp | 1575 | 1,750,135 | 1.15× 107 | 2923.077 | 4.12 × 108 |

| Senior_ex_comp | 1516 | 1.11 × 107 | 7.62 × 107 | 0 | 2.89 × 109 |

| High_rem_pack | 1394 | 5,095,505 | 5.21 × 107 | 3670.08 | 1.61× 109 |

| Sust_comp_incent | 1594 | 0.2308657 | 0.4215189 | 0 | 1 |

| Policy_sust | 1594 | 0.1781681 | 0.3827743 | 0 | 1 |

| Energy_use | 875 | 3.55 × 107 | 2.80 × 108 | 0 | 7.34 × 109 |

| Renew_energy | 1594 | 0.5376412 | 0.4987376 | 0 | 1 |

| CSR_sust_com | 1594 | 0.5621079 | 0.4962833 | 0 | 1 |

| ESG_rep | 1277 | 90.92809 | 20.83819 | 1 | 100 |

| CG_BC | 1594 | 0.174404 | 0.3795756 | 0 | 1 |

| Board_Size | 1594 | 9.280427 | 3.467873 | 2 | 23 |

| Board_Div | 1594 | 27.40046 | 14.16414 | 0 | 75 |

| Board_Sk | 1593 | 40.15431 | 22.57561 | 0 | 100 |

| Assets | 1410 | 3.81 × 1010 | 1.70 × 107 | 3.30 × 107 | 2.76 × 1012 |

| N | 1594 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EV | EBITDA | EBIT | |

| Board_m_comp | 0.228 *** | 0.196 *** | 0.290 *** |

| (0.0525) | (0.0452) | (0.0525) | |

| Senior_ex_comp | 0.0668 | 0.0968 * | 0.126 ** |

| (0.0461) | (0.0399) | (0.0460) | |

| High_rem_pack | 0.388 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.207 *** |

| (0.0537) | (0.0469) | (0.0547) | |

| CG_BC | 0.390 *** | 0.401 *** | 0.464 *** |

| (0.107) | (0.0931) | (0.106) | |

| Board_Size | 0.0614 *** | 0.0750 *** | 0.0781 *** |

| (0.0136) | (0.0118) | (0.0135) | |

| Board_Div | 0.00948 ** | 0.0103 *** | 0.0134 *** |

| (0.00332) | (0.00289) | (0.00331) | |

| Board_Sk | 0.000953 | 0.000874 | 0.00190 |

| (0.00204) | (0.00179) | (0.00203) | |

| Sust_comp_incent | 0.0683 | 0.0648 | 0.105 |

| (0.0924) | (0.0810) | (0.0933) | |

| Policy_sust | 0.363 *** | 0.335 *** | 0.151 |

| (0.0899) | (0.0792) | (0.0936) | |

| Energy_use | 0.115 *** | 0.205 *** | 0.138 *** |

| (0.0185) | (0.0161) | (0.0179) | |

| Renew_energy | 0.466 *** | 0.294 *** | 0.272 ** |

| (0.101) | (0.0892) | (0.103) | |

| CSR_sust_com | 0.337 ** | 0.332 *** | 0.402 *** |

| (0.103) | (0.0893) | (0.102) | |

| ESG_rep | 0.000356 | −0.00118 | −0.00168 |

| (0.00193) | (0.00168) | (0.00197) | |

| _cons | 9293 *** | 7862 *** | 7273 *** |

| (0.752) | (0.638) | (0.746) | |

| / | |||

| var(e.log_EV) | 1.022 *** | ||

| (0.0566) | |||

| var(e.log_EBITDA) | 0.813 *** | ||

| (0.0441) | |||

| var(e.log_EBIT) | 1.164 *** | ||

| (0.0604) | |||

| N | 653 | 680 | 742 |

| Model 1, EV | Model 2, EBITDA | Model 3, EBIT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Item-Test Correlation | Alpha | Item-Test Correlation | Alpha | Item-Test Correlation | Alpha |

| EV/EBITDA/EBIT | 0.7288 | 0.6592 | 0.7720 | 0.6848 | 0.7550 | 0.6848 |

| Board_m_comp | 0.6933 | 0.6547 | 0.6646 | 0.6943 | 0.6652 | 0.6937 |

| Senior_ex_comp | 0.6632 | 0.6621 | 0.6197 | 0.7026 | 0.6216 | 0.7018 |

| High_rem_pack | 0.6869 | 0.6607 | 0.6559 | 0.6989 | 0.6565 | 0.6983 |

| CG_BC | 0.4583 | 0.6941 | 0.4466 | 0.7258 | 0.4502 | 0.7247 |

| Board_Size | 0.5716 | 0.6765 | 0.6163 | 0.7021 | 0.6165 | 0.7017 |

| Board_Div | 0.0720 | 0.7451 | 0.2632 | 0.7489 | 0.2616 | 0.7487 |

| Board_Sk | 0.2059 | 0.7294 | 0.1423 | 0.7625 | 0.1480 | 0.7610 |

| Sust_comp_incent | 0.3578 | 0.7095 | 0.3633 | 0.7370 | 0.3623 | 0.7365 |

| Policy_sust | 0.3281 | 0.7127 | 0.3466 | 0.7384 | 0.3429 | 0.7384 |

| Energy_use | 0.5540 | 0.6861 | 0.5528 | 0.7171 | 0.5397 | 0.7175 |

| Renew_energy | 0.5082 | 0.6870 | 0.5575 | 0.7112 | 0.5550 | 0.7110 |

| CSR_sust_com | 0.5322 | 0.6831 | 0.5683 | 0.7096 | 0.5680 | 0.7091 |

| ESG_rep | 0.2376 | 0.7201 | 0.2444 | 0.7465 | 0.2444 | 0.7459 |

| Total scale | 0.7088 | 0.7360 | 0.7356 | |||

| Model 1, EV | Model 2, EBITDA | Model 3, EBIT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Chi2 | df | p-Value | Chi2 | df | p-Value | Chi2 | df | p-Value |

| EV | 801.64 | 13 | 0.000 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| EBITDA | - | - | - | 1219.58 | 13 | 0.000 | - | - | - |

| EBIT | - | - | - | - | - | - | 844 | 13 | 0.000 |

| Specifications | Model 1 EV | Model 2 EBITDA | Model 3 EBIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood ratio | |||

| Model vs. saturated chi2_ms (0) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| p > chi2 | - | - | - |

| Baseline vs. saturated chi2_bs (13) | 523,012 | 698,561 | 563,639 |

| p > chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Information criteria | |||

| AIC (Akaike’s information criterion) | 33,461.117 | 34,757.821 | 38,117.779 |

| BIC (Bayesian information criterion) | 33,528.341 | 34,825.653 | 38,186.919 |

| Baseline comparison | |||

| CFI (Comparative fit index) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| TLI (Tucker–Lewis index) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Size of residual | |||

| CD (Coefficient of determination) | 0.551 | 0.642 | 0.532 |

| SRMR (Stand. root mean sq. residual) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Variables | Model 1 EV | Model 2 EBITDA | Model 3 EBIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.A#c.Board_m_comp | 0.228 *** | 0.196 *** | 0.290 *** |

| (0.0525) | (0.0452) | (0.0525) | |

| 1.A#c.Senior_ex_comp | 0.0668 | 0.0968 * | 0.126 ** |

| (0.0461) | (0.0399) | (0.0460) | |

| 1.A#c.High_rem_pack | 0.388 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.207 *** |

| (0.0537) | (0.0469) | (0.0547) | |

| 1.A#c.Sust_comp_incent | 0.0683 | 0.0648 | 0.105 |

| (0.0924) | (0.0810) | (0.0933) | |

| 1.A#c.Policy_sust | 0.363 *** | 0.335 *** | 0.151 |

| (0.0899) | (0.0792) | (0.0936) | |

| 1.A#c.Energy_use | 0.115 *** | 0.205 *** | 0.138 *** |

| (0.0185) | (0.0161) | (0.0179) | |

| 1.A#c.Renew_energy | 0.466 *** | 0.294 *** | 0.272 ** |

| (0.101) | (0.0892) | (0.103) | |

| 1.A#c.CSR_sust_com | 0.337 ** | 0.332 *** | 0.402 *** |

| (0.103) | (0.0893) | (0.102) | |

| 1.A#c.ESG_rep | 0.000356 | −0.00118 | −0.00168 |

| (0.00193) | (0.00168) | (0.00197) | |

| 1.A#c.CG_BC | 0.390 *** | 0.401 *** | 0.464 *** |

| (0.107) | (0.0931) | (0.106) | |

| 1.A#c.Board_Size | 0.0614 *** | 0.0750 *** | 0.0781 *** |

| (0.0136) | (0.0118) | (0.0135) | |

| 1.A#c.Board_Div | 0.00948 ** | 0.0103 *** | 0.0134 *** |

| (0.00332) | (0.00289) | (0.00331) | |

| 1.A#c.Board_Sk | 0.000953 | 0.000874 | 0.00190 |

| (0.00204) | (0.00179) | (0.00203) | |

| 1.A#c._cons | 9293 *** | 7862 *** | 7273 *** |

| (0.752) | (0.638) | (0.746) | |

| / | |||

| var(e.log_EV)#1.A | 1022 *** | ||

| (0.0566) | |||

| var(e.log_EBITDA)#1.A | 0.813 *** | ||

| (0.0441) | |||

| var(e.log_EBIT)#1.A | 1.164 *** | ||

| (0.0604) | |||

| N | 653 | 680 | 742 |

References

- Conyon, M. Executive compensation and incentives. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2006, 20, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martinez, M.C.; Gallego-Alvarez, I. Do board characteristics drive firm performance? An international performance. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, M.; Kirwan, C.; Brennan, N. Comparative analysis of corporate governance theory: The agency-stewardship continuum. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual Conference of the Irish Accounting & Finance Association, Institute of Technology, Tralee, Ireland, 10–11 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kartadjumena, E.; Rodgers, W. Executive compensation, sustainability, climate, environmental concerns, and company financial performance: Evidence from Indonesian commercial banks. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molonko, L.K. Board structure, board compensation and firm profitability. Evidence from the banking industry. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Commerce, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Conyon, M.J.; He, L. Executive compensation and corporate governance in China. J. Corp. Financ. 2011, 17, 1158–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, J.; Rapp, M.S.; Wolf, M. Determinants of director compensation in two-tier systems: Evidence from German panel data. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2012, 6, 33–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparelia, R.; Njuguna, A. Relationship between board remuneration and financial performance in the Kenyan Financial Services Industry. Int. J. Financ. Res. 2016, 7, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäuble, J. The impact of external and internal corporate governance mechanisms on agency costs. Corp. Gov. 2019, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciti, V. Corporate governance and board of directors: The effect of a board composition on firm sustainability performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siminică, M.; Cristea, M.; Sichigea, M.; Noja, G.G.; Anghel, I. Well-governed sustainability and financial performance: A new integrative approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, S.H.; Lefen, L. An analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility and firm performance with moderating effects of CEO power and ownership structure: A case study of the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikon Database; Thomson Reuters: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020.

- Uyar, A.; Kilic, M.; Koseoglu, M.A.; Kuzey, K.; Karaman, A. The link among board characteristcs, corporate social responsability, and financial performance: Evidence from the hospitality and tourism industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitescu, D.C.; Cristea, M.A. Environmental, social and governance risks—New challenges for the banking business sustainability. Amfiteatru Econ. 2020, 22, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Ali, H.; Abedin, T.; Hossain, B. Directors’ remuneration and performance: Evidence from the textile sector of Bangladesh. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, N. EC: Board compensation and firm performance: The role of “independent” board members. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2008, 18, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randoy, T.; Nielsen, J. Company performance, corporate governance and CEO compensation in Norway and Sweden. J. Manag. Gov. 2002, 6, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Wilson, N. Board pay and the separation of ownership from control in U.K. SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barontini, R.; Bozzi, S. Board compensation and ownership structure: Empirical evidence for Italian listed companies. J. Manag. Gov. 2009, 15, 59–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saona, P.; Muro, L.; San Martín, P.; Baier-Fuentes, H. Board of director’s gender diversity and its impact on earnings management: An empirical analysis for select European firms. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2019, 25, 634–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, C. Love in the Time of COVID-19: The Resiliency of Environmental and Social Stocks. CEPR Discussion Papers (No. 14661). 2020, pp. 35–56. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/cprceprdp/14661.htm (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- He, H.; Harris, L. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchian, A.; Demsetz, H. Production, information costs, and economic organization. Am. Econ. Rev. 1972, I62, 777–795. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, A. Can agency costs justify the regulation of insider trading? Q. J. Austrian Econ. 2002, 5, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Int. J. Manag. 1989, 5, 341–353. [Google Scholar]

- Mukaila, A.S.; Sanda, A.U.; Garba, T. Corporate governance mechanisms and firm financial performance in Nigeria. Final Report Presented to the Biannual Research Workshop of the AERC; The African Economic Research Consortium: Nairobi, Kenya, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E.F. Agency problems and the theory of the firm. J. Polit. Econ. 1980, 88, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnan, M.; St-Onge, S.; Gélinas, P. Director compensation and firm value: A research synthesis. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2010, 7, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependency Perspective; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, E.; Haron, R.; Tahir, M.N. How director remuneration impacts firm performance: An empirical analysis of executive director remuneration in Pakistan. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2019, 19, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, B.K. Board control and CEO compensation. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, E.J.; Westphal, J.D. Director reputation, CEO-board power, and dynamics of board interlocks. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhagrasey, G.M.; Harrison, J.R.; Buchholz, R.A. Power and pay: The politics of CEO compensation. J. Manag. Gov. 1998, 2, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M. Non-linear relationships among related party transactions, financial characteristics, corporate governance, and corporate value–Analysis of high-growth and low-growth food firms. Agric. Econ. 2019, 65, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.; Pearce, J. Board of directors and corporate governance financial performance: A review and integrative model. J. Manag. 1989, 15, 291–334. [Google Scholar]

- Huse, M. Boards of Directors in SMEs: A review and research agenda. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2000, 12, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, C.M.; Ponea, Ș. Professional motivation and satisfaction. Case study at Prexi Com LTD. J. Adv. Res. Manag. 2020, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crăciun, L.; Ponea, Ş.; Băndoi, C.L. Manager and conflict in public institutions. Ann. Univ. Craiovaecon. Sci. Ser. 2010, 10, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, V. Do corporate board compensation characteristics influence the financial performance of listed companies? Proced. Soc. Behav. 2014, 109, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, T.; Zenner, M. Pay for performance? Government regulation and the structure of compensation contracts. J. Financ. Econ. 2001, 62, 453–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhebi, R.; Pattenden, K.; Swan, P.L.; Zhou, X. Australian chief executive officer remuneration: Pay and performance. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2006, 46, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyienda, M.; Oirere, C.O.; Miyogo, J. The relationship between director remuneration and performance of firms listed in the Nairobi Securities Exchange. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yatim, P. Directors’ remuneration and corporate governance in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the 7th Asia Pacific Interdisciplinary Research in Accounting Conference, Kobe, Japan, 26 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, N.A.; Wang, Z. Effects of corporate governance on capital structure: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Corp. Gov. 2012, 12, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Kennedy, D.; Weaver, S. Corporate governance and firm value: Evidence from Canadian capital markets. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2009, 6, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanwick, P.A.; Stanwick, S.D. The relationship between governance and financial performance: An empirical study of Canadian firms. Bus. Rev. Camb. 2010, 16, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ponnu, C. Corporate governance structures and the performance of Malaysian public listed companies. Int. Rev. Bus. Res. Pap. 2008, 4, 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Haat, M.H.; Abdul, R.R.; Mahenthiran, S. Corporate governance, transparency and performance of Malaysian companies. Manag. Audit. J. 2008, 23, 744–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, N.A.M. Ownership structure, corporate governance and corporate performance in Malaysia. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2010, 20, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, H.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H. Corporate governance and operating performance of Chinese listed firms. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2011, 20, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholeif, A. CEO duality and accounting-based performance in Egyptian listed companies: A re-examination of agency theory predication. Res. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2008, 8, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, B.A.; Bazaz, M.S. Corporate governance and firm performance in Iran. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2008, 4, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaway, M. A study of the relationship between company performance and CEO compensation. Am. Bus. Rev. 2000, 18, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Madura, J.; Martin, A.D.; Jessel, K.A. Determinants of CEO compensation in small publicly-traded businesses. Am. Bus. Rev. 1996, 14, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gregg, P.; Machin, S.; Szymanski, S. The disappearing relationship between directors’ pay and corporate performance. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 1993, 31, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, I.E.; Palmon, O.; Wald, J.K. CEO compensation, director compensation, and firm performance: Evidence of cronyism? J. Corp. Financ. 2006, 12, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haron, R. Do Muslim directors influence firm performance? Empirical evidence from Malaysia. J. Islam Econ. Bank. 2018, 283–305. Available online: http://irep.iium.edu.my/68215/ (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Callan, S.J.; Thomas, J.M. Relating CEO compensation to social performance and financial performance: Does the measure of compensation matter? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, S.J.; Thomas, J.M. Executive compensation, corporate social responsibility, and corporate financial performance: A multi-equation framework. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, L.S.; Thorne, L. Corporate social responsibility and long-term compensation: Evidence from Canada. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 57, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, L.S.; Thorne, L. An examination of the structure of executive compensation and corporate social responsibility: A Canadian investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, M.B.; Nelling, E.; Webb, E. Executive compensation in socially responsible firms. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2006, 14, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, P.C.; Miles, G. Corporate social responsibility and executive compensation: Exploring the link. Soc. Responsib. J. 2013, 9, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Jo, H.; Pan, C. Vice or virtue? The impact of corporate social responsibility on executive compensation. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.C. How robust is robust regression? Stata Tech. Bull. 1991, 2, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, C.; Li, Z.F.; Yang, C. Measuring firm size in empirical corporate finance. J. Bank Financ. 2018, 86, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F. An Empirical Assessment of Empirical Corporate Finance (7 June 2019). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1787143 (accessed on 23 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Comment, R.; Schwert, G.W. Poison or placebo? Evidence on the deterrence and wealth effects of modern anti-takeover measures. J. Financ. Econ. 1995, 39, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, J.; Mansi, S.A.; Maxwell, W.F. Corporate governance and firm cash holdings in the US. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 87, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magerakis, E.; Gkillas, K.; Tsagkanos, A.; Siriopoulos, C. Firm size does matter: New evidence on the determinants of cash holdings. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, S.D.; Gulzar, S.; Zeshan, G.; Iram, N. Sensitivity of firm size measures to practices of corporate fnance: Evidence from BRICS. Future Bus. J. 2020, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanapathippillaia, S.; Gul, F.; Mihret, D.; Muttakin, M.B. Compensation committees, CEO pay and firm performance. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2019, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzon, E. Dealing with and Understanding Endogeneity; StataCorp LP: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, A.A.; Aragam, B.; Zhou, Q. On Perfectness in Gaussian Graphical Models. Cornell University, 2019. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.01978 (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- Fitch, K. Learning Directed Graphical Models from Gaussian Data. Cornell University, 2019. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1906.08050 (accessed on 14 July 2020).

- Chen, X.; Wan, P.; Quan, X.; Sial, M.S. Does corporate social responsibility matter to management forecast precision? Evidence from China. Ekon. Istraz. 2020, 33, 1767–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.O. How CSV and CSR affect organizational performance: A productive behavior perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, M.O.; Malik, M. Firm performance and corporate governance through ownership structure: Evidence from Bangladesh stock market. Int. Rev. Bus. Res. Pap. 2007, 3, 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Meah, M.R.; Chaudhory, N.U. The Impact of Audit Characteristics on Firm Performance: An Empirical Study from an Emerging Economy. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 6, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suciu, M.C.; Noja, G.G.; Cristea, M. Diversity, social inclusion and human capital development as fundamentals of financial performance and risk mitigation. Amfiteatru Econ. 2020, 22, 742–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M.C.; Gallego-Álvarez, I. An international approach of the relationship between board attributes and the disclosure of corporate social responsibility issues. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z. Managerial attributes, incentives, and performance. Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2020, 9, 256–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinca, M.; Luches, L. Work integration of the roma: Between family and labor market. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirtea, M.; Botoc, C.; Jurcut, C. Risk and return analysis: Evidence from emerging markets. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2014, 13, 637–647. [Google Scholar]

- Bibu, N.; Stefea, P.; Sala, D. External and internal environment influences on SME competitiveness from the Western area of Romania. Megatrend Rev. 2009, 6, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Variables | Model 1 EV | Model 2 EBITDA | Model 3 EBITA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RREG | IV/2SLS | IV/2SLS | RREG | IV/2SLS | IV/2SLS | RREG | IV/2SLS | IV/2SLS | ||

| Management financial incentives | Board_m_comp | 0.215 *** | 0.229 *** | 0.102 ** | 0.194 *** | 0.195 *** | 0.038 | 0.304 *** | 0.289 *** | 0.061 |

| (0.0539) | (0.0531) | (0.0380) | (0.0454) | (0.0457) | (0.0284) | (0.0513) | (0.0530) | (0.0339) | ||

| Senior_ex_comp | 0.0789 | 0.0662 | 0.0102 | 0.0811* | 0.0968* | 0.0238 | 0.0861 | 0.126 ** | 0.0252 | |

| (0.0473) | (0.0466) | (0.0331) | (0.0401) | (0.0404) | (0.0248) | (0.0450) | (0.0465) | (0.0292) | ||

| High_rem_pack | 0.392 *** | 0.389 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.308 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.0917 ** | 0.314 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.124 *** | |

| (0.0551) | (0.0543) | (0.0386) | (0.0471) | (0.0474) | (0.0291) | (0.0535) | (0.0553) | (0.0344) | ||

| Sustainable development dimensions | Sust_comp_incent | 0.0853 | 0.0693 | 0.0218 | 0.0973 | 0.0645 | 0.0224 | 0.113 | 0.105 | 0.0485 |

| (0.0949) | (0.0935) | (0.0659) | (0.0814) | (0.0819) | (0.0499) | (0.0913) | (0.0943) | (0.0588) | ||

| Policy_sust | 0.364 *** | 0.364 *** | 0.322 *** | 0.321 *** | 0.338 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.134 | 0.156 | 0.408 *** | |

| (0.0921) | (0.0908) | (0.0643) | (0.0795) | (0.0800) | (0.0491) | (0.0914) | (0.0944) | (0.0596) | ||

| Energy_use | 0.118 *** | 0.115 *** | 0.129 | 0.203 *** | 0.204 *** | 0.0940 *** | 0.127 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.0994 *** | |

| (0.0190) | (0.0187) | (0.0142) | (0.0161) | (0.0162) | (0.0106) | (0.0175) | (0.0181) | (0.0114) | ||

| Renew_energy | 0.507 *** | 0.467 *** | 0.205 ** | 0.274 ** | 0.297 ** | 0.421 | 0.286 ** | 0.277 ** | 0.584 | |

| (0.104) | (0.102) | (0.0730) | (0.0896) | (0.0901) | (0.0558) | (0.100) | (0.103) | (0.0652) | ||

| CSR_sust_com | 0.361 *** | 0.337 ** | 0.320 | 0.290 ** | 0.333 *** | 0.111 * | 0.287 ** | 0.404 *** | 0.205 ** | |

| (0.105) | (0.104) | (0.0746) | (0.0897) | (0.0903) | (0.0562) | (0.0992) | (0.103) | (0.0651) | ||

| ESG_rep | 0.0255 | 0.0382 | 0.0583 | −0.0184 | −0.0222 | −0.0139 | 0.00655 | −0.0221 | −0.0405 | |

| (0.0900) | (0.0887) | (0.0621) | (0.0776) | (0.0781) | (0.0475) | (0.0895) | (0.0925) | (0.0573) | ||

| Corporate governance and board characteristics | CG_BC | 0.366 *** | 0.389 *** | 0.456 | 0.418 *** | 0.400 *** | 0.379 | 0.536 *** | 0.463 *** | 0.112 |

| (0.110) | (0.108) | (0.0779) | (0.0935) | (0.0941) | (0.0587) | (0.103) | (0.107) | (0.0682) | ||

| Board_Size | 0.0561 *** | 0.0616 *** | 0.0240 | 0.0784 *** | 0.0757 *** | 0.00624 | 0.0815 *** | 0.0792 *** | 0.0745 | |

| (0.0139) | (0.0137) | (0.0998) | (0.0119) | (0.0119) | (0.00760) | (0.0131) | (0.0136) | (0.0888) | ||

| Board_Div | 0.0106 ** | 0.00946 ** | 0.00375 | 0.0112 *** | 0.0103 *** | 0.0413 * | 0.0153 *** | 0.0134 *** | 0.00562** | |

| (0.00341) | (0.00336) | (0.00239) | (0.00290) | (0.00292) | (0.00180) | (0.00324) | (0.00334) | (0.00212) | ||

| Board_Sk | 0.00231 | 0.000916 | 0.00246 | 0.00156 | 0.000801 | 0.000616 | 0.00198 | 0.00178 | 0.00176 | |

| (0.00209) | (0.00206) | (0.00145) | (0.00180) | (0.00181) | (0.00111) | (0.00199) | (0.00205) | (0.00128) | ||

| Firm size | Total assets | 0.732 *** | 0.711 *** | 0.644 *** | ||||||

| (0.0288) | (0.0214) | (0.0192) | ||||||||

| _cons | 9027 *** | 9144 *** | 0.778 | 7237 *** | 7858 *** | 0.298 | 6090 *** | 7221 *** | 0.531 | |

| (0.863) | (0.851) | (0.690) | (0.722) | (0.726) | (0.504) | (0.823) | (0.850) | (0.571) | ||

| N | 653 | 653 | 640 | 680 | 680 | 660 | 742 | 742 | 721 | |

| R2 | 0.548 | 0.551 | 0.778 | 0.653 | 0.642 | 0.866 | 0.564 | 0.532 | 0.817 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Noja, G.G.; Cristea, M.; Jurcut, C.N.; Buglea, A.; Lala Popa, I. Management Financial Incentives and Firm Performance in a Sustainable Development Framework: Empirical Evidence from European Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187247

Noja GG, Cristea M, Jurcut CN, Buglea A, Lala Popa I. Management Financial Incentives and Firm Performance in a Sustainable Development Framework: Empirical Evidence from European Companies. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187247

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoja, Gratiela Georgiana, Mirela Cristea, Cecilia Nicoleta Jurcut, Alexandru Buglea, and Ion Lala Popa. 2020. "Management Financial Incentives and Firm Performance in a Sustainable Development Framework: Empirical Evidence from European Companies" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187247

APA StyleNoja, G. G., Cristea, M., Jurcut, C. N., Buglea, A., & Lala Popa, I. (2020). Management Financial Incentives and Firm Performance in a Sustainable Development Framework: Empirical Evidence from European Companies. Sustainability, 12(18), 7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187247