How We Can Enhance Spectator Attendance for the Sustainable Development of Sport in the Era of Uncertainty: A Re-Examination of Competitive Balance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Competitive Balance and Attendance

2.2. Measurement Issues

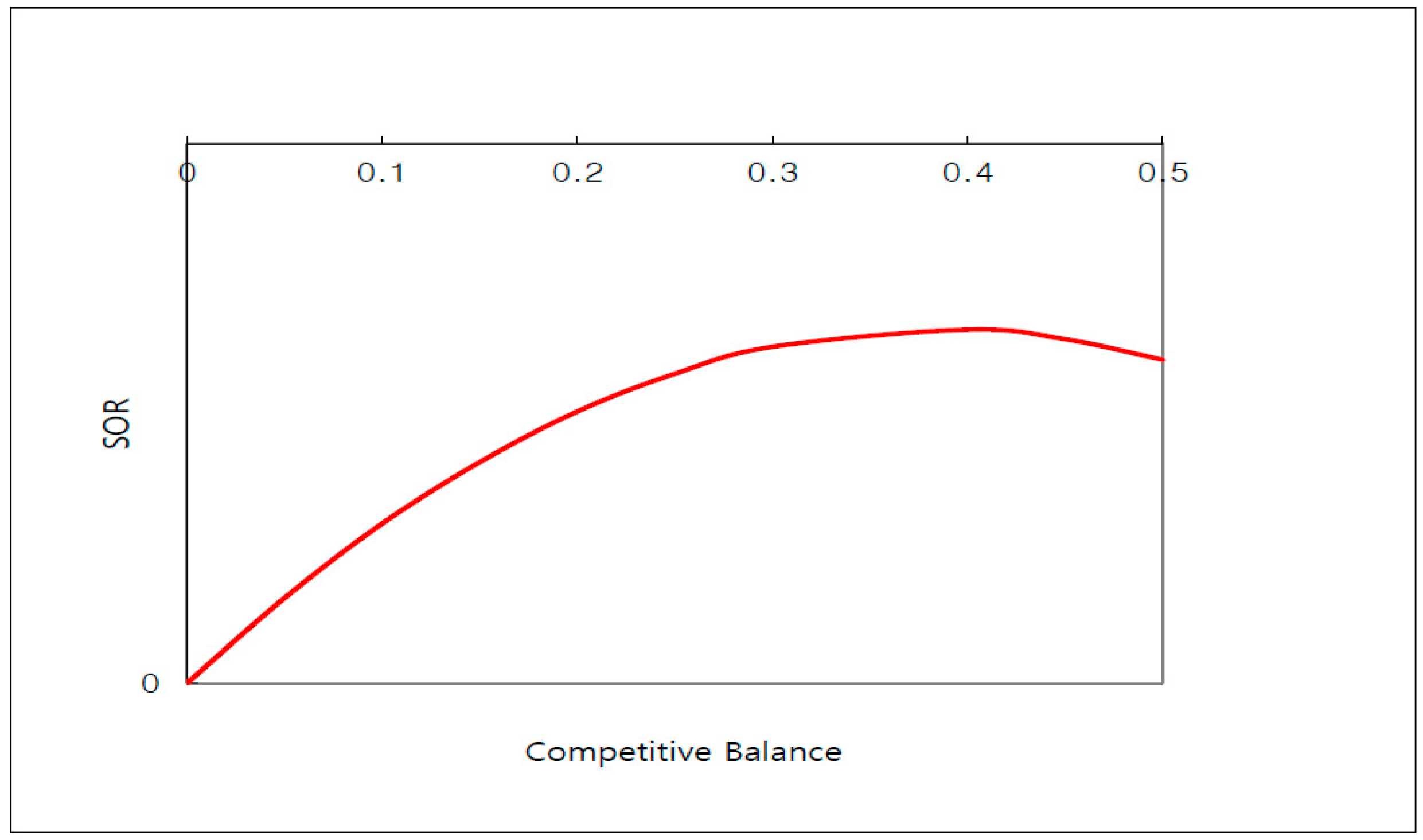

2.3. Competitive Balance and SOR

2.4. Other Factors Affecting SOR

2.4.1. Demographic and Socioeconomic Factors of Teams’ Hometowns

2.4.2. Television Audience

2.4.3. Scheduling

3. Methods

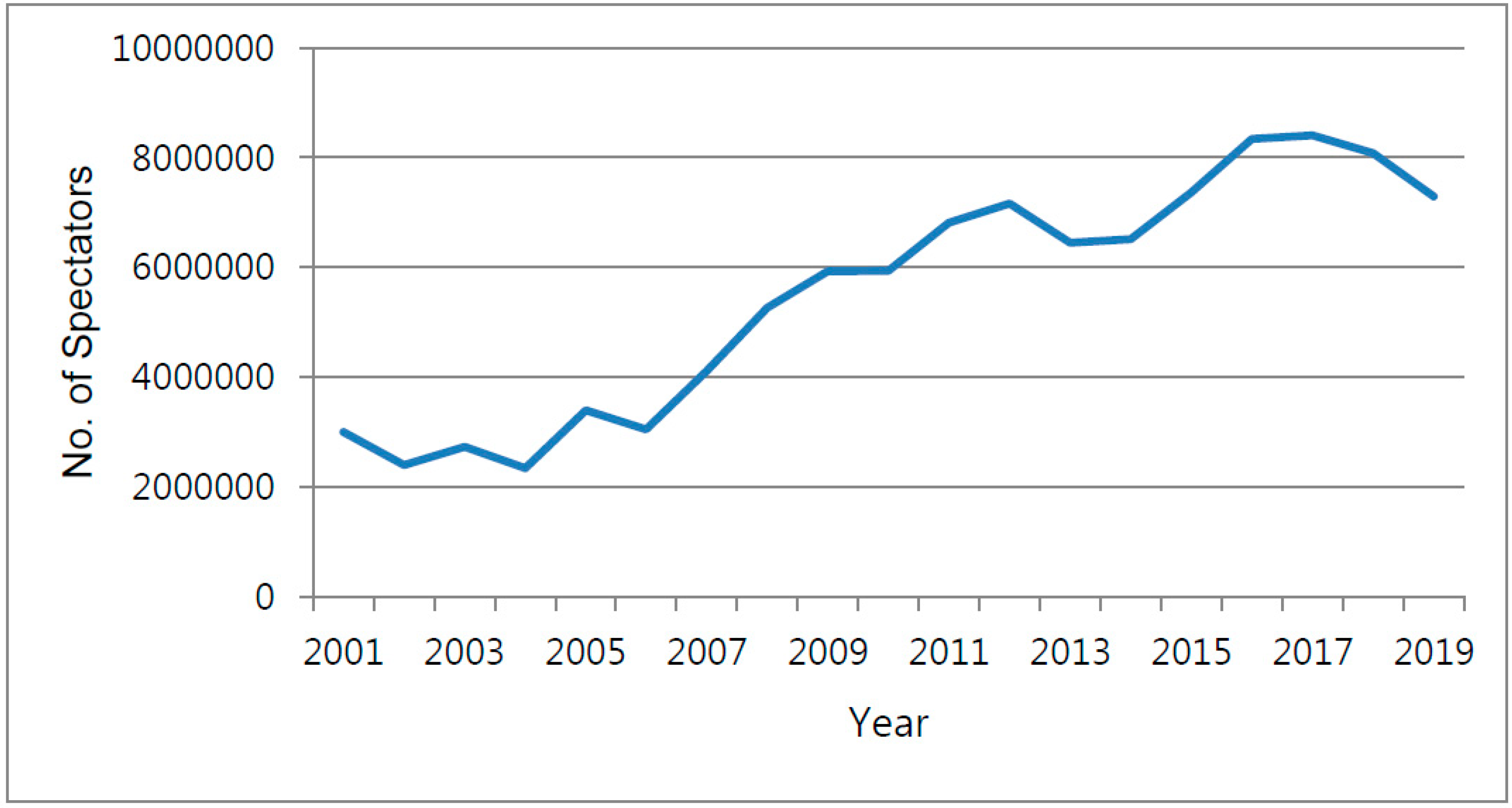

3.1. Data

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Seat Occupancy Rate (SOR)

3.2.2. Winning Percentage (WP)

3.2.3. Competitive Balance (CB)

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Empirical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Practice

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Team | Home Stadium | Population of Hometown (in 1000) | Stadium Capacity (in Person) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doosan Bears | Seoul Jamsil Stadium | 9805 | 25,000 |

| LG Twins | Seoul Jamsil Stadium | 9805 | 25,000 |

| Nexen Heroes | Seoul Gocheok Dome | 9805 | 17,000 |

| KT Wiz | Suwon KT Wiz Park | 1231 | 22,000 |

| SK Wyverns | Incheon SK Happy Dream Park | 2913 | 26,000 |

| Hanwha Eagles | Daejeon Hanwha Life Eagles Park | 1535 | 13,000 |

| Samsung Lions | Daegu Samsung Lions Park | 2461 | 24,000 |

| Lotte Giants | Busan Sajik Stadium | 3440 | 26,800 |

| NC Dinos | Masan Baseball Stadium | 1069 | 11,000 |

| Kia Tigers | Gwangju-Kia Champions Field | 1501 | 20,500 |

References

- Baade, R.A.; Tiehen, L.J. An analysis of major league baseball attendance, 1969–1987. J. Sport Soc. Issues 1990, 14, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, H.A. Empowering people, facilitating community development, and contributing to sustainable development: The social work of sport, exercise, and physical education programs. Sport Educ. Soc. 2005, 10, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenkorf, N. Sustainable community development through sport and events: A conceptual framework for sport-for-development projects. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, I.; Darby, P. Sport and the sustainable development goals: Where is the policy coherence? Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2018, 54, 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W. A study of the economic validation of public goods generated by a professional sport stadium. Korean J. Sport Manag. 2015, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Van Reeth, D. The finances of professional cycling teams. In The Economics of Professional Road Cycling; Larsen, D.J., Van Reeth, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 11, pp. 55–82. [Google Scholar]

- JoongAng Daily. Pro Baseball beyond 500 Billion Won of Sales: 10 Million Spectators Coming Soon. 2018. Available online: http://news.joins.com/article/22823755 (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MCST). Sports Industry White Paper, 2017. Sejong-si, Korea. 2018. Available online: http://index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtPageDetail.do?idx_cd=1662 (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Hill, B.; Green, B.C. Repeat attendance as a function of involvement, loyalty, and the sportscape across three football contexts. Sport Manag. Rev. 2000, 3, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Lee, Y.H. A business analysis of Asian baseball leagues. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2016, 11, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, S.; Kim, Y. Sports Economics; Orae: Seoul, Korea, 2011. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Coates, D.; Harrison, T. Baseball strikes and the demand for attendance. J. Sports Econ. 2005, 6, 282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, R.T. The effect of marquee players on sports demand: The case of U.S. major league soccer. J. Sports Econ. 2017, 18, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxcy, J.; Mondello, M. The impact of free agency on competitive balance in North American professional team sports leagues. J. Sport Manag. 2006, 20, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, J.J.; Findlay, M. The Effects of the Bosman ruling on national and club teams in Europe. J. Sports Econ. 2012, 13, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbarth, T.; Walzel, S.; Van Eekeren, F. ‘European-ness’ in social responsibility and sport management research: Anchors and avenues. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewes, M. Competition and efficiency in professional sports leagues. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2003, 3, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scelles, N.; Helleu, B.; Durand, C.; Bonnal, L. Professional sports firm values. J. Sports Econ. 2016, 17, 688–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, J.; Macdonald, R. Demand for sport. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2003, 19, 478–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellmer, E.M.M.; Rynne, S.B. Professionalisation of action sports in Australia. Sport Soc. 2018, 22, 1742–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.M. Japanese professional soccer attendance and the effects of regions, CB, and rival franchises. Int. J. Sport Financ. 2012, 7, 309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W.; Tan, T.C. The rise of sport in the Asia-Pacific region and a social scientific journey through Asian-Pacific sport. Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, R.; Kang, J.H.; Lee, Y.H. KBO and international sports league comparisons. In The Sports Business in the Pacific Rim: Economics and Policy; Lee, Y.H., Fort, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MCST). AVERAGE Number of Spectators per Game by Major Professional Sports. 2020. Available online: http://index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtPageDetail.do?idx_cd=1662 (accessed on 23 August 2020).

- DeSchriver, T.D.; Jensen, P.E. Determinants of spectator attendance at NCAA Division II football contests. J. Sport Manag. 2002, 16, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Rodríguez, P. The determinants of football match attendance revisited: Empirical evidence from the Spanish Football League. J. Sports Econ. 2002, 3, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, N.; Pedersen, P.M. Examining determinants of sport event attendance: A multilevel analysis of a major league baseball season. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, J.W., Jr.; Nelson, R.A.; Richardson, T.V. Competitive balance and game attendance in Major League Baseball. J. Sports Econ. 2007, 8, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, R.G. Attendance and Price Setting. In Government and the Sports Business; Nol, R.G., Ed.; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1974; pp. 115–157. [Google Scholar]

- Dietl, H.M.; Grossmann, M.; Lang, M. Competitive balance and revenue sharing in sports leagues with utility-maximizing teams. J. Sports Econ. 2011, 12, 284–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.A. The value of competition: Competitive balance as a predictor of attendance in spectator sports. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2009, 11, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, P.D.; King, N. Competitive balance measures in sports leagues: The effects of variation in season length. Econ. Inq. 2014, 53, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbalist, A.S. Competitive balance in sports leagues. J. Sports Econ. 2002, 3, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, D.; Humphreys, B.R. Week to week attendance and competitive balance in the National Football League. Int. J. Sport Financ. 2010, 5, 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Fort, R.; Maxcy, J. Comment: Competitive balance in sports leagues: An introduction. J. Sports Econ. 2003, 4, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.; Fenn, A.J.; Spenner, E.L. The impact of free agency and the salary cap on competitive balance in the National Football League. J. Sports Econ. 2006, 7, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, J.; Fort, R. Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Team Sports; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fort, R.; Lee, Y.H. Structural change, competitive balance, and the rest of the major leagues. Econ. Inq. 2007, 45, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, B.R. Alternative measures of competitive balance in sports leagues. J. Sports Econ. 2002, 3, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Gratton, C. The Economics of Sports and Recreation: An Economic Analysis; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hodiri, M.; Quirk, J. An economic model of a professional sports league. J. Political Econ. 1971, 79, 1302–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottenberg, S. The baseball players’ labor market. J. Political Econ. 1956, 64, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmert, H.G. The Economics of Professional Team Sports; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.R.; Madura, J.; Zuber, R.A. The short run demand for major league baseball. Atl. Econ. J. 1982, 10, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, R.; Rosenman, R. Streak management. In Sports Economics: Current Research; Fizel, E.G.J., Hadley, L., Eds.; Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT, USA, 1999; pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, R.J.; Wachsman, Y.; Weinbach, A.P. The role of uncertainty of outcome and scoring in the determination of fan satisfaction in the NFL. J. Sports Econ. 2010, 12, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, V.; Massey, P.; Massey, S. Analysing match attendance in the European Rugby Cup: Does uncertainty of outcome matter in a multinational tournament? Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 17, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacheti, A.; Gregory-Smith, I.; Paton, D. Uncertainty of outcome or strengths of teams: An economic analysis of attendance demand for international cricket. Appl. Econ. 2014, 46, 2034–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakina, E.; Gasparetto, T.; Barajas, A. Football fans’ emotions: Uncertainty against brand perception. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds, M.A.; von Allmen, P.; Matheson, V.A. The Economics of Sports, 6th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scully, J.R. The Business of Major League Baseball; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fort, R.; Quirk, J. Cross-subsidization, incentives, and outcomes in professional team sports leagues. J. Econ. Lit. 1995, 33, 1265–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Noll, R.G. The economics of sports leagues. In Law of Professional and Amateur Sports; Clark Boardman: Deerfield, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S. A bias-corrected estimator of competitive balance in sports leagues. J. Sports Econ. 2018, 20, 479–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depken, C.A. Free-agency and the competitiveness of Major League Baseball. Rev. Ind. Organ. 1999, 14, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Croix, S.J.; Kawaura, A. Rule changes and competitive balance in Japanese professional baseball. Econ. Inq. 1999, 37, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, P.D.; Ryan, M.; Weatherston, C.R. Measuring competitive balance in professional team sports using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2007, 31, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizak, D.; Neral, J.; Stair, A. The adjusted churn: An index of competitive balance for sports leagues based on changes in team standings over time. Econ. Bull. 2007, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kaempfer, W.H.; Pacey, P.L. Televising college football: The complementarity of attendance and viewing. Soc. Sci. Q. 1986, 67, 176–185. [Google Scholar]

- Schollaert, P.T.; Smith, D.H. Team racial composition and sports attendance. Sociol. Q. 1987, 28, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welki, A.M.; Zlatoper, T.J. US professional football: The demand for game-day attendance in 1991. Manag. Decis. Econ. 1994, 15, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, D.; Humphreys, B.R.; Zhou, L. Reference-dependent preferences, loss aversion, and live game attendance. Econ. Inq. 2014, 52, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, R.; García-Bernal, J.; Fernández-Olmos, M.; Espitia-Escuer, M.A. Expected quality in European football attendance: Market value and uncertainty reconsidered. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2015, 22, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascher, D.A.; Solmes, J. Do fans want close contests? A test of the uncertainty of outcome hypothesis in the National Basketball Association. SSRN Electron. J. 2007, 2, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robinson, M.J.; DeSchriver, T.D. Consumer differences across large and small market teams in the National Professional Soccer League. Sport Mark. Q. 2003, 12, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, C.D.; Nagel, M.; DeSchriver, T.D.; Brown, M.T. Facility age and attendance in Major League Baseball. Sport Manag. Rev. 2005, 8, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buraimo, B.; Simmons, R. A tale of two audiences: Spectators, television viewers and outcome uncertainty in Spanish football. J. Econ. Bus. 2009, 61, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, K.; Winfree, J.A. Comparison of television and gate demand in the National Basketball Association. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buraimo, B. Stadium attendance and television audience demand in English league football. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2008, 29, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimbridge, M.; Cameron, S.; Dawson, P. Satellite television and the demand for football: A whole new ball game? Scott. J. Political Econ. 1996, 43, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, D.; Simmons, R.; Szymanski, S. Broadcasting, attendance and the inefficiency of cartels. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2004, 24, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.J.; Weinbach, A.P. Determinants of attendance in the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League: Role of winning, scoring, and fighting. Atl. Econ. J. 2011, 39, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, D.; Simmons, R. New issues in attendance demand. J. Sports Econ. 2006, 7, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Baseball Organization (KBO). 2018. Available online: http://www.koreabaseball.com (accessed on 20 December 2018).

- Korea Baseball Organization (KBO). History. 2019. Available online: http://www.koreabaseball.com/History/Crowd/GraphYear.aspx (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Lemke, R.J.; Leonard, M.; Tlhokwane, K. Estimating attendance at major league baseball games for the 2007 season. J. Sports Econ. 2009, 11, 316–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeil. The 2160 Thousand TV Watchers for the Opening Games of the Professional Baseball ‘without Spectators’. 2020. Available online: http://www.m-i.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=707559 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Korea Institute of Sport Science. A Study of Development Plans by Four Major Sports; Unpublished Research Report; Korea Institute of Sport Science: Seoul, Korea, 2015. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Seat occupancy rate (SOR) | 0.57 | 0.24 |

| Home team winning % against visiting team (HWP) | 0.51 | 0.24 |

| Home team winning % for whole seasons (HWP_T) | 0.50 | 0.12 |

| Competitive balance with a visiting team (CB_V) | 0.18 | 0.16 |

| Competitive balance with entire teams (CB_T) | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Income of home team’s province (INCH) | 18,107 | 1698 |

| Income of visiting team’s province (INCA) | 18,101 | 1671 |

| Population of home team’s hometown (POPH) | 432 | 368 |

| Population of visiting team’s hometown (POPA) | 437 | 365 |

| TV viewer ratings of home team games (TVH) | 1.00 | 0.31 |

| TV viewer ratings of visiting team games (TVA) | 1.00 | 0.31 |

| Weekends dummy (WEDUM) | 0.52 | 0.50 |

| Independent Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | |||

| Income of home team’s province (INCH) | 0.39 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.38 *** |

| Income of visiting team’s province (INCA) | 0.35 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.35 *** |

| Population of home team’s hometown (POPH) | −0.31 *** | −0.12 * | −0.29 *** |

| Population of visiting team’s hometown (POPA) | −0.28 *** | −0.36 *** | −0.28 *** |

| TV viewer ratings of home team games (TVH) | 0.17 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.17 *** |

| TV viewer ratings of visiting team games (TVA) | 0.34 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.35 *** |

| Weekends dummy (WEDUM) | 0.43 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.43 *** |

| Winning percentage | |||

| Home team winning % against visiting team (HWP) | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Home team winning % for whole seasons (HWP_T) | 0.23 *** | 0.23 *** | |

| Competitive balance | |||

| Competitive balance with a visiting team (CB_V) | −0.01 | 0.00 | |

| Competitive balance with entire teams (CB_T) | 0.17 *** | 0.08 + | |

| CB_V squared (CBSQ_V) | 0.05 | 0.04 | |

| CB_T squared (CBSQ_T) | −0.22 *** | −0.10 * | |

| R2 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.36 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sung, S.H.; Hong, D.-S.; Sul, S.Y. How We Can Enhance Spectator Attendance for the Sustainable Development of Sport in the Era of Uncertainty: A Re-Examination of Competitive Balance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177086

Sung SH, Hong D-S, Sul SY. How We Can Enhance Spectator Attendance for the Sustainable Development of Sport in the Era of Uncertainty: A Re-Examination of Competitive Balance. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):7086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177086

Chicago/Turabian StyleSung, Sang Hun, Doo-Seung Hong, and Soo Young Sul. 2020. "How We Can Enhance Spectator Attendance for the Sustainable Development of Sport in the Era of Uncertainty: A Re-Examination of Competitive Balance" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 7086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177086

APA StyleSung, S. H., Hong, D.-S., & Sul, S. Y. (2020). How We Can Enhance Spectator Attendance for the Sustainable Development of Sport in the Era of Uncertainty: A Re-Examination of Competitive Balance. Sustainability, 12(17), 7086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177086