1. Introduction

Online shopping is an emerging service. Judging by the characteristics of this service, zero service failure is extremely difficult to achieve during the service process [

1]. To thrive and sustain amid fierce competition, service providers must make service recovery to ensure customers have a satisfactory shopping experience. In addition, customer-switching cost is low in an online shopping environment; consequently, customers will switch products or service providers if recovery quality falls short of customer expectation. Therefore, online businesses should attach more importance to service recovery compared with brick-and-mortar stores [

2]. Previous studies of service recovery focused on brick-and-mortar retailing, whereas research on online-shopping service recovery is scant [

3]. McColl-Kennedy and Sparks (2003) indicated that customers use perceived justice to assess the responsibilities borne by service providers [

4]. Therefore, we used the perceived justice theory as the framework of this study to investigate the justice that online shoppers perceive after receiving service recovery and subsequent service recovery satisfaction.

Rowley (2004) noted the importance of online branding by stating that in an electronic trading environment, where the amount of tangible interaction is significantly reduced, e-commerce business owners must secure favorable brand perception among customers [

5]. Min-Hsin Huang (2011) argued that when customers have favorable brand perception of a business, the perception will serve as the basis of customer evaluation concerning the performance of future service recovery and will play a vital role in the service recovery that businesses make [

6]. In previous studies on service recovery, the majority of scholars adopted the perspective of perceived justice to explore consumer evaluation of service recovery. Nevertheless, most of these studies focused on the positive and negative emotions of consumers triggered by perceived justice or the results of the interaction between service failure and various types of compensation, and few scholars have adopted the perspective of brands to explore the relationship between service recovery and perceived justice [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Based on the expectancy–disconfirmation theory [

12], we anticipate that customers have relatively higher expectation of the service quality of strong brands. Consequently, strong brands must maintain a level of service that matches the brand status. Otherwise, customers are likely to feel a gap between actual service performance and the quality they expect and subsequently perceive unjust treatment. Hence, customer–brand perception plays a vital role in the relationship between business service performance and customer-perceived justice. To resolve problems with business service and to fill the gap in previous research, this study incorporates brand equity and brand identity, two vital factors influencing customer–brand perception, to explore the process from service recovery to perceived justice.

A brand can be defined as a name, term, sign, symbol, design, or combination of them which is intended to identify the goods and services of one seller or group of sellers and to differentiate them from those of competitors [

13]. The term brand equity was first used widely by US advertising practitioners in the early 1980s [

14]. Brand equity is a vital concept in marketing, management and branding studies [

15]. However, in a business environment where the Internet is used as the media, the characteristics of the Internet are unique brand capital. In addition, brand power also differs. Therefore, brand equity should be reviewed in the context of an online environment [

16]. Kim, Sharma, and Setzekorn (2002) argued that introducing the concept of brand equity is beneficial for e-commerce business owners to build strong Internet brands [

17]. Laudon, Traver, and Elizondo (2007) stated that brand equity symbolizes the image and service quality of online shopping sites, attracting consumers to trust the brands of online shopping sites [

18]. They confirmed that brands are still the element used to segment and emphasize the products and services of businesses in online shopping.

Brand equity derives from the positive associations that consumers have of a brand based on previous experience and current memory [

19,

20]. According to the expectancy-disconfirmation theory, when the service recovery made by a firm with high brand equity fails to meet the high expectations held by customers, their level of satisfaction is the gap between expected perception and brand performance. Because the firm has high brand equity, consumers are even more disappointed; this feeling has a stronger negative effect on customer-perceived justice. Numerous studies have examined the relationship between brand equity and consumer products or services [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] or investigated brand management [

26,

27,

28]. However, there are few scholars have explored how brand equity moderates the effects of online service recovery on customer-perceived justice. Therefore, this study adopted the perspective of brand equity to analyze the effects of service recovery on customer-perceived justice.

Individual perception of online brands is an unelectable influencing factor when firms make service recovery. Brand identity is important because it allows consumers to show their uniqueness and status [

29]. A strong customer–brand identity indicates that the concept represented by a brand is consistent with the self-concept of consumers [

30]. Lam, Ahearne, Hu, and Schillewaert (2010) found that brand identity influences customer purchase behavior and service satisfaction related to a brand [

31]. Furthermore, negative word of mouth can easily reach individuals via social groups because of the instantaneity of social media in the online environment. Therefore, online businesses, in particular, should secure customer–brand identity [

9,

32]. Customers with a strong brand identity have relatively in-depth brand knowledge of the firm as well as a strong connection with and high expectation of the brand [

32]. Consumer perception of service recovery is influenced by their perception of the brand [

6]. According to the expectancy-disconfirmation theory, customers with a strong brand identity tend to have high service expectations when service failure occurs in a firm. Consequently, a drop in firm performance can easily jeopardize customer-perceived justice. Therefore, this study examines how brand identity moderates the relationship between service recovery and perceived justice. Previous research on the influence of brand equity on the relationship between service recovery and perceived justice has overlooked differences between individuals and a brand at the overall level [

33,

34,

35]. Considering this, we employed hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) [

36] to develop the research framework of this study, the purpose being to precisely measure the relationship between organizations and customers.

This study presents the following key contributions. (a) We used the perceived justice theory to measure customer perception of service recovery and subsequent service recovery satisfaction. Although numerous scholars have employed this framework in previous studies [

33,

34,

35], few studies have adopted the perspective of individual brand perception to measure the influence of service recovery on customers. Therefore, this study incorporated brand identity, a factor at the individual level, to examine how online brand identity moderates the relationship between service recovery and perceived justice. (b) Although scholars have studied whether business brand equity affects the relationship between service recovery and service recovery satisfaction [

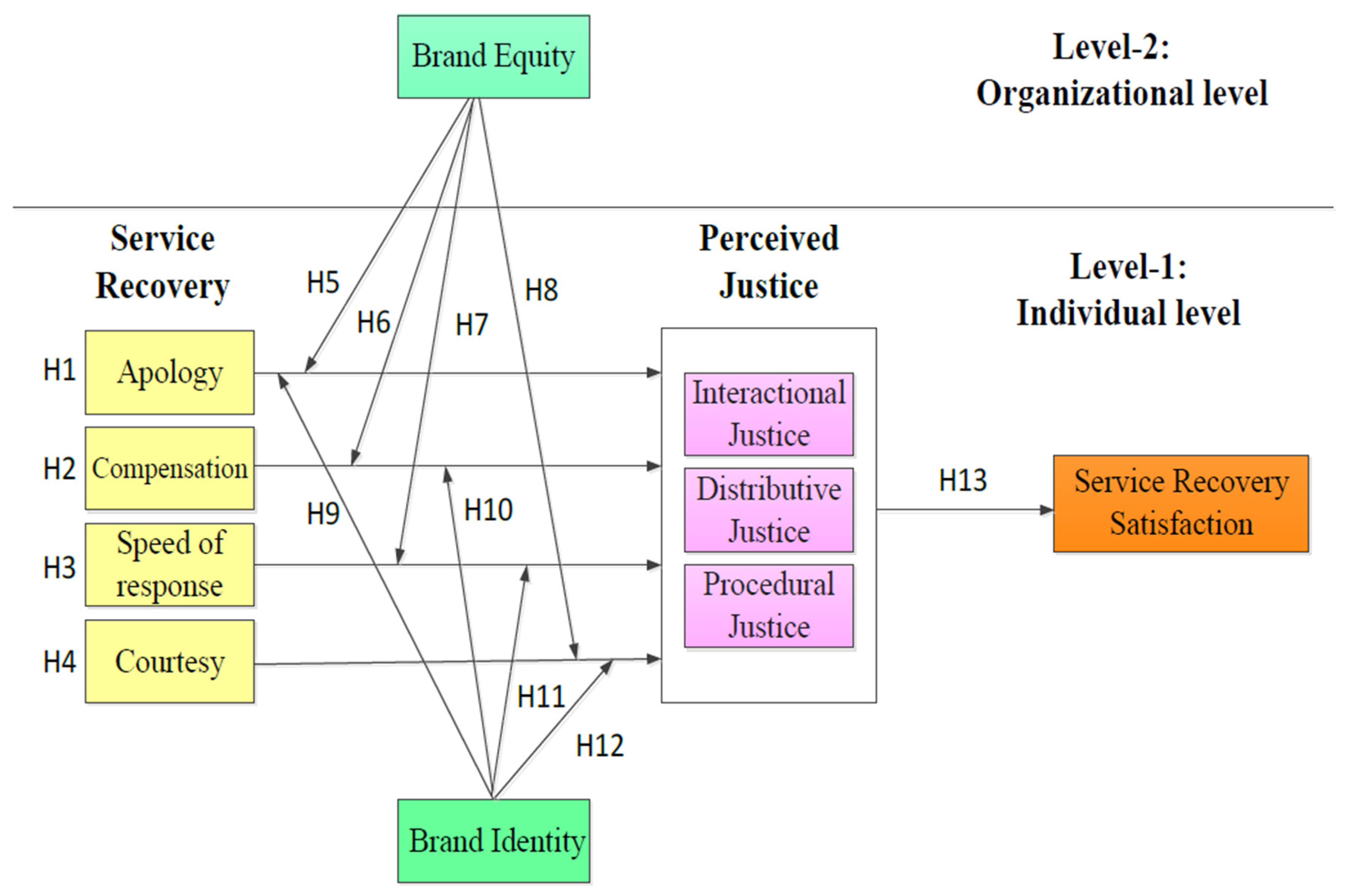

6], few studies have explored whether brand equity affects the relationship between service recovery and perceived justice. This study incorporated brand equity to explore the moderating effect of this factor and used brand equity as a variable at the organizational level to investigate whether brand equity has a cross-level moderating effect and whether the individual level moderates the relationship between service recovery and perceived justice. (c) Finally, we adopted an HLM as the method of this study, performing precise evaluations of variables at differing levels. Brand perception was divided into two levels: brand equity at the organizational level and brand identity at the individual level. Previous studies focused on the relationships among variables at a single level. By contrast, we introduced a moderating mechanism to examine cross-level relationships: (1) a moderating model at the individual level: brand identity affects the relationship between service recovery and customer-perceived justice; (2) a moderating model at the organizational level: brand equity affects the relationship between service recovery and customer-perceived justice.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study explored the influence of various service recovery approaches on customer-perceived justice. Apology, speed of response, compensation, and courtesy were used as typical service recovery approaches to examine the relationships these approaches have with perceived justice. The results showed these service recovery approaches had significant positive effects on the perceived justice of online shoppers (H1, H2, H3, and H4). This finding is consistent with those of several previous studies [

7,

47,

97] and thus verified the conclusions in the previous literature. Therefore, customer-perceived justice is enhanced when online shopping service providers offer appropriate compensation, handle the failures immediately, respond to customer requests instantly, act courteously, and apologize to customers after service failures occur. Simultaneously, customer perception of the service providers is improved. In addition, we investigated the influence of perceived justice on service recovery satisfaction. The results indicated that perceived justice had a positive relationship with service recovery satisfaction (H13). In other words, customers are satisfied with the service recovery a firm makes when the recovery matches customer expectation and customer-perceived justice. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies [

33,

51,

55,

98].

Second, few studies have explored whether the relationship between service recovery and perceived justice is moderated. Although a few scholars have used company reputation and brand equity as moderators to examine the relationship between service recovery and service recovery satisfaction [

6,

99], these moderators both focused on the individual level. Nevertheless, the recent rise in virtual communities has allowed most consumers to formulate purchase decisions by referencing information and experience shared by members of virtual communities. Furthermore, online brands have differing target customers and brand images. Considering the disparity, we employed brand equity as a variable at the organizational level to moderate the influence of service recovery on perceived justice.

When we used brand equity as the moderator, the results showed that brand equity moderated the relationship between compensation and courtesy on perceived justice (H6 and H8), indicating that high brand equity undermines the positive influence of compensation and courtesy on perceived justice. Therefore, we conclude that because compensation is related to the cost–benefit allocation of a firm [

100], customers can easily tie compensation to the overall performance of a firm. Customers that do not receive the high compensation they expect are likely to perceive disconfirmation with the brand awareness they hold. Additionally, courtesy, which determines the service management quality of service personnel, is a bridge through which customers and firms interact [

51]. Customers expect firms with high equity to deliver high-quality service, and consequently, courtesy undermines the influence of high brand equity on compensation and perceived justice.

Third, we hypothesized that brand identity, a factor at the individual level, moderates the relationship between service recovery and perceived justice. No scholars have adopted a similar framework, and we examined the relationships among these factors. The results show that individual customers’ brand identity moderates and weakens the influence of compensation and courtesy on perceived justice (H10, H11). Based on this finding, we conclude that customers believe that brands they identify with perceive the customers as unique individuals [

31]; therefore, consumers with a strong brand identity have high expectations of firm policies and expect customized service [

79]. In addition, compared with brands customers have a weak identity with, customers have significantly higher expectations of the attitude demonstrated by service providers which whom customers highly identify. Therefore, according to the expectancy–disconfirmation theory, consumers with a strong brand identity are likely to feel dissatisfied when they receive compensations and courteous service recovery made by a brand, resulting in the perception of unjust experience [

12]. Brand equity, a factor at the organizational level, represents aggregated customer perception of a brand and externalized value. However, brand identity is a unique perception people have of a brand, indicating that a customer recognizes the brand as a unique existence. By contrast, customers consider apology and speed of response and indication of the performance and personal quality of service personnel; therefore, these two factors do not affect overall customer perception of the brand. Hence, brand identity does not moderate the influence of apology and speed of response on perceived justice.

Fourth, the results of this study show that brand equity and brand identity have no significant moderating effect on the influence of apology and speed of response on perceived justice (H5 and H7) (H9 and H11). Statistical results relating to the two factors were similar. Previous studies have argued that customer brand identity is correlated with brand equity [

101,

102]. Therefore, we conclude that apology can be viewed as a form of psychological compensation, which reflects the empathy a firm shows toward customer complaints [

103]. However, because of the sophisticated orders, product complexity, and customer alienation in an online environment [

2], service providers might act without empathy when filling a massive amount of orders for customers they have no physical contact with. Therefore, we conclude online shoppers might have a higher failure tolerance of products and service provided in this context and they do not associate the failure with brand performance.

Fifth, the speed of response is the flexibility and speed with which service personnel respond to customers. Because online retailers employ a large force of customer service personnel, customers might be served by differing service providers when communicating their problems to customer service. The service provided by various people changes over time and space; therefore, customers consider service efficiency a result of the emotional act and instant performance of service providers. In particular, customers with a strong brand identity perceive a unique connection between themselves and the brand. Hence, the personal behavior and performance of individual service providers do not change customer perception of brand image, and customers do not associate individual staff behavior with the brand.

Based on the law of diminishing marginal utility, the effects of sincere apology and speedy responses are significant when customers receive the first response. However, customers are less impressed and perceive no difference after the service recovery made by a firm reaches a high level or when the customer receives frequent apologies from service personnel. According to this law, customers would transfer the limited resources they have to satisfy other desires after customers have received a certain amount of product service. Therefore, to achieve satisfaction, customers transfer their attention to the compensation measures a firm adopts. In this situation, differentiated service attitude and compensation can have significant influence on customer perception. Furthermore, marginal utility is unlikely to decline; therefore, customers with a strong brand identity tend to have high expectations of service personnel performance and the anticipated compensation provided by firms with high equity.

5.1. Theoretical Implication

This study has several implications and makes a number of contributions. The findings of this study are described as follows: (a) The study based on the online service recovery methods proposed by Mostafa (2014) [

58], we investigated the effects of various types of recovery methods on customer-perceived justice and on subsequent service recovery satisfaction; (b) we explored whether the brand equity of business organizations has a moderating effect on the relationship between business service recovery and customer-perceived justice; and (c) we examined whether the brand identity of individual customers has a moderating effect on the relationship between business service recovery and customer-perceived justice. (d) Regarding the methodology of this study, previous studies on service recovery primarily adopted linear structural equation models. By contrast, this study adopted HLM as the research framework because brand perception differs at various levels and adopting HLM allows us to precisely understand the influence of brand identity and brand equity on the relationship between service recovery and perceived justice. This method enhances the explanatory power of the results. These findings are vital developments and contributions we make to the field of e-commerce brand marketing.

5.2. Managerial and Practical Implications

With the prevalence of the Internet and mobile devices, competition among online shopping sites is increasingly fierce. Brand management is a vital issue for improving company competitiveness [

21]. First, the results of this study show that high brand equity can undermine the positive influence of service recovery on customer-perceived justice. In other words, when service failure occurs in firms with high brand equity, customers are sensitive to the inadequacy in service recovery and are therefore dissatisfied with the service. Simultaneously, customer satisfaction increases when firms with high brand equity adopt efficient service recovery measures. These results indicate that service providers must respond to customers immediately and provide and create valuable products and services that match brand equity if firm managers intend to establish and maintain high brand equity [

6]). In this study, the hypotheses regarding how brand equity moderates the influence of apology and speed of response were rejected. This is possibly because the study was conducted on the subject of online shopping, where customer evaluation of speed of response and apology might be separated from overall brand evaluation. Therefore, in addition to improving service personnel management and firm policy communication, firm managers should improve the response efficiency, spontaneity, and active attitude in service recovery, particularly in an environment featuring massive and complex transactions such as the Internet. In other words, service providers should enhance convenience, which is a discerning feature of online shopping.

Furthermore, the results of this study show that a strong brand identity can undermine the positive influence of service recovery on customer-perceived justice. Specifically, when service failure occurs in firms a customer has a strong identification and commitment with, the customer is likely to heed the inadequacy of service recovery and feel dissatisfied with the service. Based on this finding, we have the following recommendations: first, to serve customers with a strong brand identity, firm management should formulate flexible policies, ensure service providers receive sufficient training, and encourage a friendly service attitude. Furthermore, customers with a strong identity consider themselves unique to the brand [

32]. Therefore, we recommend that online shopping brands set up a Very Important Person (VIP) system, providing customized service and highly flexible compensation mechanisms for customers with a strong brand identity. In the age of big data and information, firms holding a large amount of customer information have greater competitive advantages.

Second, we found brand equity and brand identity had no effect on the influence of apology and speed of response on recovery perception. Apology and speed of response, as two recovery strategies, hardly differ between various brands. According to the law of diminishing marginal utility, when firms apologize and actively respond to customer concerns, these actions result in minor differences in customer perception after the recovery measures exceed a high standard. Therefore, we recommend that firms invest their resources in courtesy and compensation, two types of recovery that can result in significant difference in customer perception. To achieve this goal, we recommend online shopping brands set up a customer management system and formulate a well-defined and customized courteous procedure for front-line service personnel to follow when encountering complaints filed by customers with a strong brand identity. In addition, service providers should offer compensations (in the form of coupons or gifts) to ensure the experience exceeds the expectation of customers with a strong brand identity.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

The following suggestions are proposed as a reference for future studies. First, online shopping as an emerging industry is popular among young users, considering that technology products are necessary for making purchases. Therefore, obtaining middle-aged and elderly samples is difficult. Consequently, we are unable to precisely analyze and explore overall social perception of online brands and the future significance of online shopping. Hence, we recommend future scholars focus on the middle-aged and elderly population to comprehensively investigate the interaction between online brands and service recovery.

Second, we focused on the influence of online brand equity and customer brand perception on customer perception of service recovery. Nevertheless, in addition to brands, the recent rise in online social communities should not be overlooked [

104]. These communities have significant influence on firms and individuals. Therefore, we recommend future scholars use the connotation of social community as a moderator to further examine the influence of online communities on service recovery.