Climate Change—Challenges and Response Options for the Port Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Green Port Concept

1.2. Climate Change

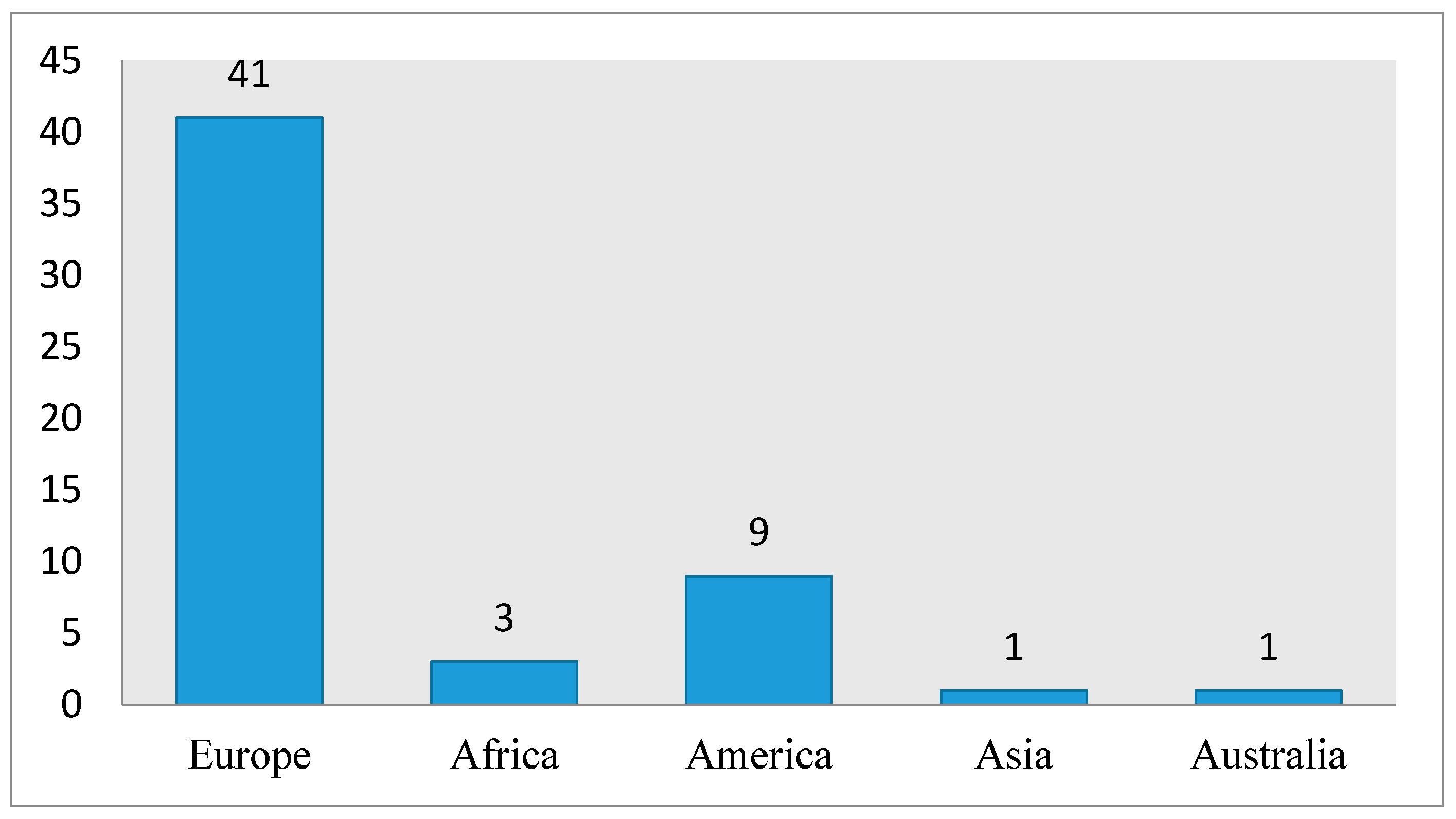

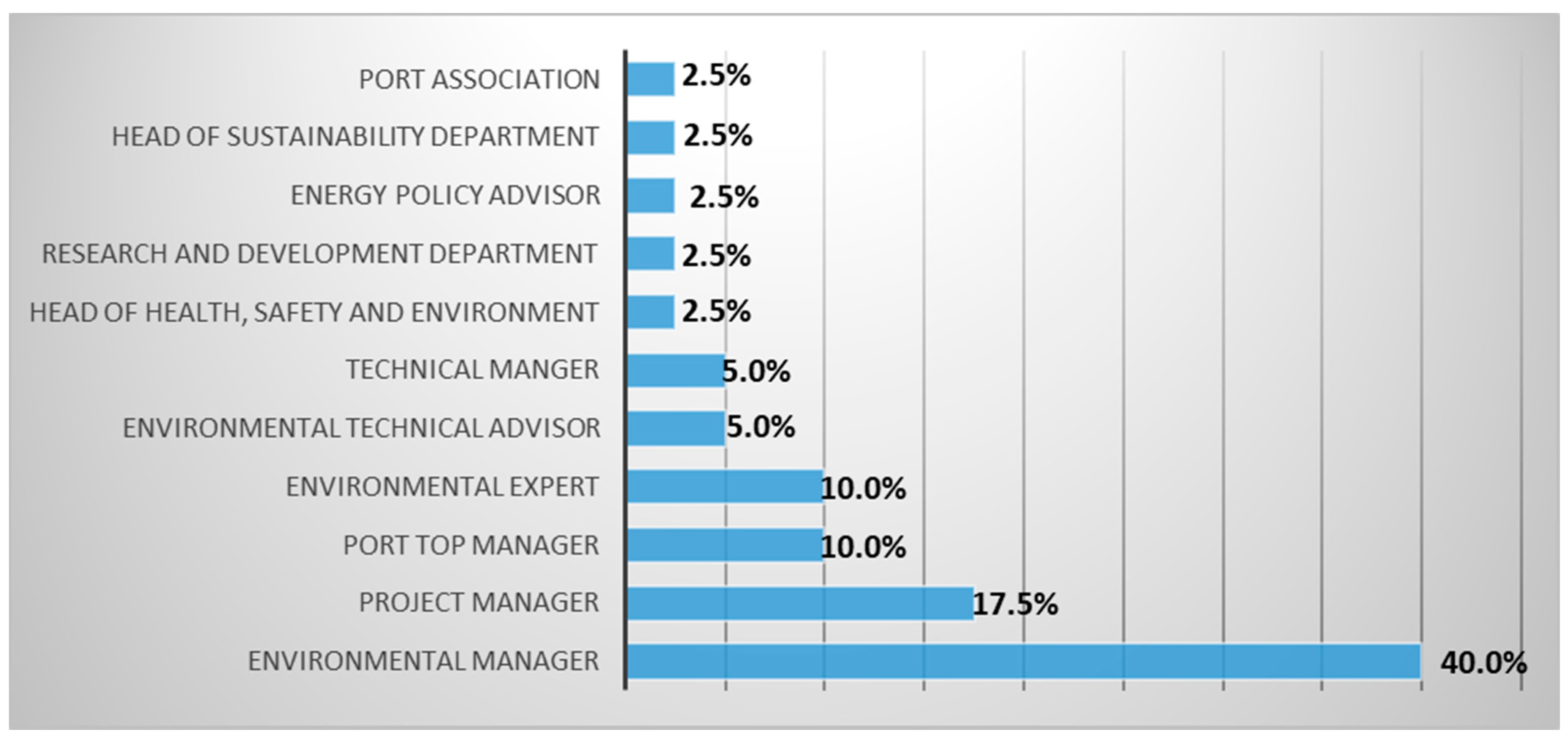

2. Materials and Methods

- Identification of the top environmental priorities in the participant portsThe participants were asked to fill in the five top environmental priorities in their organization in order of importance. The survey also asked if they were monitored and if performance indicators were selected for them.

- Questions on the relationship of the ports with climate issuesA set of five questions with a Yes/No answer were included here, asking about topics such as the impact of climate change in their organizations or the preparation of risk assessment plans. Examples could be added for each question.

- Questions on Carbon Footprint ManagementA set of four questions with different type of answer were introduced in this section. The first one was Yes/No question, the second was a ranking one with five options and the last two were open questions.

- Analysis of the scheme of Carbon FootprintIn this case, three Yes/No questions were asked to the participants in relation to issues such as the role in reducing the GHG emissions or the need of a common Carbon Footprint scheme.

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Aspects

3.2. Climate Change

3.3. Management of Carbon Footprint

3.4. Carbon Footprint Scheme

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample Questionnaire

- Delegate’s name (Optional)

- Email (Optional)

- Organization (Optional)

- Job description

- 1.

- What are the Top-5 priority Environmental priority issues/aspects in your Organization *?

Priority Issue/Aspect Monitored? YES, or NO Environmental Performance Indicator(s) Selected? YES, or NO 1 2 3 4 5 * In this Survey, the word organization refers to any of the following: Port Authority, Terminal Operator, Shipping Company, Maritime Logistics Support, or other port-related entity. - 2.

- Climate Change

Issue Yes, or No Details/Example (a) Is climate change impacting your organization *? (In terms of operations, functions, construction projects etc) (b) Has your organization * prepared risk assessment specifically related to climate change? (Detailed? Basic? Contingency? EIA?). (c) Is your organization * collaborating with other, third-party, organizations on the issue of climate change? (d) Is your organization * collecting data/information on climate change? (e) Is your organization * using, or is it aware of, PIANC WG 178 Guidelines/Tool kit. * In this Survey, the word organization refers to any of the following: Port Authority, Terminal Operator, Shipping Company, Maritime Logistics Support, or other port-related entity. - 3.

- Carbon Footprint Management

- (a)

- Does your organization report on Carbon emissions? YES, or NO (please circle)

- (b)

- What are the main drivers to implement Carbon Management?—please prioritize in the following table where 1= highest priority, 5 = lowest

Drivers Priority (Allocate 1–5) Compliance with emerging regulations Stakeholder pressure to reduce environmental impacts Leadership role in Carbon management practices Potential to influence practice and regulation through innovation and investment Opportunity to reduce and offset emissions from infrastructure development - (c)

- Which stakeholders are the key players for development of a Carbon management program in your organization?

- (d)

- In your opinion, what are the major challenges and problems of developing and implementing a Carbon management program? What are your recommended best options?

- 4.

- Carbon Footprint Scheme

- (a)

- Do you consider that ports have a role to play in reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHG) from shipping? YES, or NO (Please circle)

- (b)

- Do you consider GHG emissions from shipping generated in the port area should be included as third-party emissions in Carbon Footprint of the port? YES, or NO (Please circle).

- (c)

- Do you consider that a common, port-sector Carbon Footprint Scheme would benefit individual Port Authorities and the Port-Sector as a whole? YES, or NO (Please circle).

References

- Chiu, R.-H.; Lin, L.-H.; Ting, S.-C. Evaluation of Green Port Factors and Performance: A Fuzzy AHP Analysis. Math. Probl. Eng. 2014, 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, N.; Hassani, A.; Jones, D.; Nguye, H.H. Sustainability ranking of the UK major ports: Methodology and case study. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2015, 78, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Laxe, F.; Bermúdez, F.M.; Palmero, F.M.; Novo-Corti, I. Sustainability and the Spanish port system. Analysis of the relationship between economic and environmental indicators. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 113, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasopoulos, D.; Kolios, S.; Stylios, C. How Will Greek Ports Become Green Ports? Geo-Eco-Marina 2011, 17, 73–80. Available online: https://geoecomar.ro/website/publicatii/Nr.17-436 2011/09_anastapoulos_BT.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- UNCTAD. Sustainable Development for Ports. Report UNCTAD (SDD/Port); UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993; Volume 1, p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi, M.R.; Acciaro, M.; Walker, T.R.; Magnan, G.M.; Adams, M.; Magnan, G.M. Corporate sustainability in Canadian and US maritime ports. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, C.; Vreugdenhil, H.; De Jong, M. A sustainability assessment of ports and port-city plans: Comparing ambitions with achievements. Transp. Res. Part. D Transp. Environ. 2017, 57, 84–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerman, J.; Höjer, M. How much transport can the climate stand?—Sweden on a sustainable path in 2050. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1944–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroneos, C.J.; Nanaki, E. Environmental assessment of the Greek transport sector. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 5422–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, E.; Lazarou, C. Influence of European passenger cars weight to exhaust CO2 emissions. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprinz, D.; Luterbacher, U. International Relations and Global Climate Change. Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research Report No. 21 1996. p. 105. Available online: https://www.pik-potsdam.de/research/publications/pikreports/.files/pr21.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). IPCC Factsheet: Timeline—Highlights of IPCC History. 2015. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/04/FS_timeline.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- United Nations. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 1992. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework. Review of European Community and International Environmental Law. 1998. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf. (accessed on 26 December 2018).

- IAPH (International Association of Ports and Harbors). IAPH Tool Box for Port Clean Air Programs. 2010. Available online: http://iaphtoolbox.wpci.nl/DRAFTIAPHTOOLBOX dea.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2019).

- IMO (International Maritime Organization). Third IMO Greenhouse Gas Study 2014. 2014. Available online: http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/PollutionPrevention/AirPollution/Documents/Third Greenhouse Gas Study/GHG3 Executive Summary and Report.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2019).

- Olmer, N.; Comer, B.; Roy, B.; Mao, X.; Rutherford, D. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Global Shipping. 2013–2015; International Council on Clean Transport: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; p. 27. Available online: https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/Global-468 shipping-GHG-emissions-2013-2015_ICCT-Report_17102017_vF.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Winnes, H.; Styhre, L.; Fridell, E. Reducing GHG emissions from ships in port areas. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2015, 17, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, D.; Rigot-Müller, P.; Mangan, J.; Lalwani, C. The role of sea ports in end-to-end maritime transport chain emissions. Energy Policy 2014, 64, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Manchester, T.; Starkey, R.; Manchester, T. Shipping and Climate Change: Scope for Unilateral Action. The University of Manchester. 2010, p. 83. Available online: http://shippingefficiency.org/sites/shippingefficiency.org/files/Tyndall.pdf 475 (accessed on 5 March 2019).

- United Nations. Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf. (accessed on 26 December 2018).

- Le Quéré, C.; Andrew, R.M.; Canadell, J.G.; Sitch, S.; Korsbakken, J.I.; Peters, G.P.; Manning, A.C.; Boden, T.A.; Tans, P.P.; Houghton, R.A.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2016, 8, 605–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, F.; Spahni, R. Rates of change in natural and anthropogenic radiative forcing over the past 20,000 years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NOAA and ESRL (National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration and Earth System Research Laboratory). Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. 2019. Available online: https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/full.html (accessed on 8 April 2019).

- BPO. Collaboration—Maritime Industry’s Path to 2030. 2019. Available online: http://www.bpoports.com/collaboration-maritime-industry’s-path-to-2030.html (accessed on 6 April 2019).

- Marlog (The International Maritime Transport and Logistics Conference “Marlog 8”). Alexandria, Egypt, 2019. Available online: https://marlog.aast.edu/en/home (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- PIANC (The World Association for Waterborne Transport Infrastructure). Climate Change Adaptation Planning for Ports and Inland Waterways, EnviCom WG Report n° 178. 2020; p. 190. ISBN 978-2-87223-001-3. Available online: https://www.pianc.org/uploads/publications/reports/WG-178.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Puig Duran, M. Methodology for the selection and implementation of environmental aspects and performance indicators in ports. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Cataluña, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ESPO (European Sea PortsOrganization). Environmental Report 2018 EcoPortsinsights 2018. 2018; pp. 1–18. Available online: https://www.espo.be/media/ESPO Environmental Report 2018.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2018).

- ESPO (European Sea PortsOrganisation). Environmnetal Report 2019 EcoPortsSights 2019; ESPO: Abertillery, UK, 2019; pp. 1–23. Available online: https://www.espo.be/media/Environmental Report-2019 499 FINAL.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- Scott, H.; McEvoy, D.; Chhetri, P.; Basic, F.; Mullett, J. Climate change adaptation guidelines for ports. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast. 2013; pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-1-921609-83-1. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274570189_Climate_change_adaptation_guidelines_for_503 ports (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Azarkamand, S.; Wooldridge, C.; Darbra, R.M. Review of Initiatives and Methodologies to Reduce CO2 Emissions and Climate Change Effects in Ports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WPCI (World Ports Climate Initiative). Carbon Footprinting for Ports, Guidance Document. 2010; pp. 1–83. Available online: http://wpci.iaphworldports.org/data/docs/carbonfootprinting/PV_DRAFT_WPCI_Carbon_Footprinting_510 Guidance_Doc-June-30-2010_scg.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- IMO (International Maritime Organization). Initial IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships. Resolution MEPC. 304 (72), 2018. Available online: http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Documents/Resolution%20MEPC.304%2872%29%20on%20Initial%20IMO%20Strategy%20on%20reduction%20of%20GHG%20emissions%20from%20ships.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- WPSP (World Ports Sustainability Program). World Ports Sustainability Program. 2018; pp. 1–4. Available online: https://sustainableworldports.org/wp-content/uploads/wpsp-declaration.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Davarzani, H.; Fahimnia, B.; Bell, M.; Sarkis, J. Greening ports and maritime logistics: A review. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 48, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aregall, M.G.; Bergqvist, R.; Monios, J. A global review of the hinterland dimension of green port strategies. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 59, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zis, T.P. Prospects of cold ironing as an emissions reduction option. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pr. 2019, 119, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Greenport Congress Survey | ESPO Survey 2018 | ESPO Survey 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Energy consumption | Air quality | Air quality |

| 2 | Air quality | Energy consumption | Energy consumption |

| 3 | Waste | Noise | Climate Change |

| 4 | Noise | Relationship with Local community | Noise |

| 5 | Water quality | Ship Waste | Relationship with Local community |

| 6 | Climate change | Land planning | Ship Waste |

| 7 | Dredging operation | Climate change | Port Waste |

| 8 | Land planning | Water quality | Land planning |

| 8 | Carbon Footprint | ||

| 9 | Relationship with Local community | Dredging operation | Dredging operation |

| 10 | Transportation system in the logistic chain | Garbage/port waste | Water quality |

| Issue | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Energy consumption | 54 |

| Air quality | 52 |

| Waste | 49 |

| Noise | 38 |

| Water quality | 32 |

| Climate change | 13 |

| Dredging operation | 14 |

| Land planning | 4 |

| Carbon Footprint | 7 |

| Relationship with Local community | 2 |

| Issue | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Energy consumption | 49 |

| Air quality | 38 |

| Waste | 34 |

| Noise | 27 |

| Water quality | 20 |

| Climate change | 13 |

| Dredging operation | 11 |

| Land planning | 4 |

| Carbon Footprint | 4 |

| Local community | 0 |

| Drivers | Priority |

|---|---|

| Leadership role in Carbon management practices | 1 |

| Compliance with emerging regulations | 2 |

| Potential to influence practice and regulation through innovation and investment | 3 |

| Opportunity to reduce and offset emissions from infrastructure development | 4 |

| Stakeholder pressure to reduce environmental impacts | 5 |

| The Key Stakeholders | Number | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Port Operators | 18 | 25% |

| 2 | Ship Owners | 10 | 15% |

| 3 | Government | 7 | 9% |

| 4 | Senior manager | 6 | 8% |

| 5 | Municipality | 5 | 6% |

| 5 | Port Authorities | 5 | 6% |

| 6 | Environmental department | 4 | 4% |

| 7 | Customers | 3 | 3% |

| 8 | Other | 17 | 24% |

| Major Challenges and Problems | Number | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Data collection | 18 | 26% |

| 2 | Measuring and calculating Data | 14 | 20% |

| 3 | Coordination among stakeholders | 7 | 10% |

| 3 | Legislation | 7 | 10% |

| 4 | External costs | 6 | 9% |

| 4 | Limited to local footprint | 6 | 9% |

| 4 | Set boundaries for measuring shipping emission | 6 | 9% |

| 5 | Others | 5 | 7% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azarkamand, S.; Balbaa, A.; Wooldridge, C.; Darbra, R.M. Climate Change—Challenges and Response Options for the Port Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6941. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176941

Azarkamand S, Balbaa A, Wooldridge C, Darbra RM. Climate Change—Challenges and Response Options for the Port Sector. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):6941. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176941

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzarkamand, Sahar, Alsnosy Balbaa, Christopher Wooldridge, and Rosa Mari Darbra. 2020. "Climate Change—Challenges and Response Options for the Port Sector" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 6941. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176941

APA StyleAzarkamand, S., Balbaa, A., Wooldridge, C., & Darbra, R. M. (2020). Climate Change—Challenges and Response Options for the Port Sector. Sustainability, 12(17), 6941. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176941