1. Introduction

Since the 2000s, the sharing economy has rapidly developed and has become one of the most significant global economic trends [

1]. It has been a buzzword since the 2008 financial crisis and has garnered worldwide attention. Companies operating or claiming to operate on this model, such as Uber and Airbnb, are becoming more and more popular among consumers. The increasing popularity of powerful information and communication technology (ICT), especially smartphone technology, in daily life provides a sound basis for furthering the development of the sharing economy. It has been predicted that the total value of the global sharing economy will grow from USD 15 billion in 2014 to an estimated value of USD 335 billion by 2025—almost 23 times greater within a span of 12 years [

2]. It is also estimated that 70% of Europeans [

3] and 72% of Americans [

4] have participated in the sharing economy.

In China, with the advancement and innovative application of information technology, the sharing economy has also entered a new stage of development. From 2015 to 2019, its market size in China has increased steadily. The annual growth rate in 2016 even reached 95.74%, though it has slowed down since then, and from 2018 on once popular businesses such as bike-sharing and peer-to-peer (P2P) lending have experienced setbacks (

Figure 1).

From 2016 to 2019, the average growth rate of China’s sharing economy revenue was significantly higher than that of the traditional economy. In 2019, online car-hailing passenger traffic accounted for 37.1% of the total taxi passenger traffic, and the penetration rate among internet users reached 47.4%. Shared accommodation accounted for 7.3% of the total lodging industry revenue, and the penetration rate was 9.7% [

5].

The term “sharing economy” was included in the Chinese Government Report from 2016 to 2018, as well as the “13th Five-Year Plan,” announced in 2016. Currently, such kinds of business are concentrating on transportation, accommodation, knowledge and skills, life service, among others. It is estimated that 800 million people participated in the sharing economic activities, with 78 million service providers employing 6.23 million workers in 2019 [

5]. This means that more than half of the population in China has participated in the sharing economy in different capacities.

The sharing economy has been framed as a socio–economic model that is able to reduce environmental burden and to increase social bonding and collaboration [

6,

7]. It has economic, environmental and social impacts on sustainability [

8,

9]. (1) Economic impacts: the sharing economy is an economic opportunity to generate business revenue, to empower individuals and to promote micro-entrepreneurs’ development and job creation [

10,

11,

12,

13]. As a disruptive innovation, the sharing economy could decentralize established and traditional socio–economic structures [

6,

14]. It is a subversion of the capitalist economic paradigm [

15,

16]. (2) Environmental impacts: the sharing economy enables access to and optimizes the use of underutilized resources [

17,

18,

19]. It is a sustainable form of consumption that will minimize hyper-consumption and excessive spending habits among some [

19,

20,

21,

22]. (3) Social impacts: the sharing economy could increase the participants’ feeling of solidarity and trust and promote social connections [

23,

24]. Therefore, it has the potential for creating social bonding and relationships and establishing a participatory society and community [

25,

26].

The sharing economy has experienced both explosive growth and setbacks in China in recent years. It has also experienced tightened government regulation and rationalization in the past two years. Policy and academic discussion continue but without a clear understanding of this label. Only by clarifying the concept and mapping it can we draw a clear boundary around the sharing economy and have meaningful discussions about these economic activities in China. Based on a comprehensive review of the existing literature, this paper maps out the organizing essential elements of the sharing economy and proposes a classification of the sharing economy. We will explore the problems of the current usage of the term. We will also illustrate the misuse of the label according to our proposed organizing framework and classifications and seek to exclude them from the discussion of the sharing economy.

2. Literature Review Process

The literature review of this paper has gone through two stages. In the first stage, we conducted a thorough search for relevant literature and identified the key themes and questions. In the second stage, we mainly focused on reviewing those articles about definitions and concepts of the sharing economy, identified and synthesized those relevant arguments for the purposes of deriving our framework and mapping.

2.1. Preliminary Literature Search

In order to determine the study themes and questions, this paper conducted a broad literature review. We conducted a search, with the terms sharing economy as well as those relevant terms such as collaborative consumption, access economy, platform economy, peer to peer economy or sharing in the title, abstract and keywords from the database of Web of Science. With a further review of selected highly cited articles, we have formulated a sound understanding of the existing research on sharing economy and the focus for further conceptual examination.

2.2. Specific Literature Search and Selection

After deciding to focus on the conceptual construction and clarification of the sharing economy, we conducted a specific literature search based on a combination of the search terms sharing economy with meaning, concept, conception or definition in the title, abstract and keywords from the English databases of EBSCO, Science Direct, Springer, Web of Science and the Chinese database of CNKI. Then, after a cursory review of the articles, we consolidated a core list of the literature for more critical conceptual discussion.

3. From Sharing to the Sharing Economy

Many scholars have questioned the meaning of sharing [

27,

28,

29]. Literally, it means to use or have something jointly. Sharing contains the act of division, distribution and communication, and often echoes certain human values (such as equality, mutuality, honesty, openness, empathy, and caring) which shape social relationships [

28].

The meaning and practice of sharing are constantly evolving and developing [

30]. Sharing could be traced back to the early hunter–gatherer society formed by close kinship and friends [

31,

32,

33]. When material resources were extremely scarce, people had to hunt and farm and share the fruits of labor. Survival of these collective societies depended on sharing and cooperation [

34,

35]. Sharing also existed in agricultural and industrial societies, in which the act of sharing was not solely for survival but to create better living conditions. Intangible goods, such as feelings, hobbies, beliefs, knowledge and culture were also shared. While there was still limits to human mobility, sharing activities were mostly social behaviors confined to community members or acquaintances. Sharing occurred mainly through face-to-face contacts, and the purpose of sharing was primarily non-profit and mutual.

In the current internet age, sharing can be mediated by technology in cyberspace, effectively connecting strangers from distant areas in order to share a wider range of goods (

Table 1). “Digital sharing,” involves a computer-mediated platform which gives specific users access to online content such as images, videos, and software, among others. With the rapid development of social media platforms, digital sharing also focuses on the so-called Web 2.0 platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, which care more about user-generated content.

Sharing in the internet age is no longer limited to acquaintances within a specific geographical space but often extends to strangers in wider spaces connected through the internet community. Sharing is a fundamental and constitutive element of the internet world [

28]. In the mobile internet age, with the popularization of technologies such as 4G, smartphones, mobile payment, positioning, and evaluation systems through mobile Internet platforms (i.e., mobile applications), strangers can quickly and effectively share tangible resources with one another. Through this process, sharing among acquaintances for survival or reciprocity in close geographical proximate spaces extends to sharing as for-profit economic activities among distant strangers. It is the latter form that we often refer to as the sharing economy.

In the sharing economy, people consume collaboratively and share the pleasures of ownership with lower costs through various forms of sharing: bartering, trading, renting and swapping [

19]. The sharing economy gradually emerged as a business model: systematizing non-profit oriented reciprocal sharing into organized economy activities and taking a fraction of the sharing (or “transaction”) fee [

36,

37].

4. Conceiving the Sharing Economy: Collaborative, Access-Based and Platform-Mediated

The sharing economy is regarded as both economic and social behavior involving the redistribution and consumption of resources. Review of the literature found that various labels have been used to describe this type of activity: “the mesh” [

38], the “gig economy” [

39], or “connected consumption” [

40,

41,

42]. However, more often, it is described as a form of “collaborative consumption” [

19,

43,

44], the “collaborative economy” [

37,

45,

46,

47,

48], the “peer economy” [

49], the “P2P Economy” [

50,

51], “access-based consumption” [

31,

52] and the “platform economy” [

53].

4.1. Collaborative Consumption or Collaborative Economy

Collaborative consumption is often a synonym for the sharing economy. Felson and Spaeth [

54] (p. 614) coined the term “collaborative consumption” and describe it as “those events in which one or more persons consume economic goods or services in the process of engaging in joint activities with one or more others.”. This sharing is mostly free and reciprocal.

Botsman and Rogers [

43] expand the concept by defining the collaborative consumption as “systems of organized sharing, bartering, lending, trading, renting, gifting, and swapping” (p. 30) that give people the same benefits of ownership with reduced personal cost and lower environmental impact. This definition has been supported by some scholars [

10,

42,

55]. Botsman and Rogers [

19,

43] further divide collaborative consumption into three categories: “product service systems” (i.e., the access to products without owning them, such as Zipcar and Ziploc), “redistribution markets” (i.e., the re-allocation of goods, such as Freecycle, SwapTree and eBay), and “collaborative lifestyles” (i.e., the exchange of less-tangible assets—time, space, skill and money—such as Airbnb, Landshare and Lending Club).

Collaborative consumption refers to “people coordinating the acquisition and distribution of a resource for a fee or other compensation” [

36] (p. 1597). Ertz et al. [

56] (p. 32) define it as “the set of resource circulation schemes that enable consumers to both receive and provide, temporarily or permanently, valuable resources or services through direct interaction with other consumers or through an intermediary.”. The consumer has a two-sided role and can be the provider as well. It is also a “peer-to-peer-based activity of obtaining, giving, or sharing access to goods and services, coordinated through community-based online services” [

57] (p. 2047).

4.2. P2P or Peer Economy

Originating from the field of computer science, the P2P (peer-to-peer) or peer economy is a decentralized model whereby individuals directly transact goods and services or cooperate in production with each other without an intermediary third-party [

50]. Based on modern technology, person-to-person marketplaces connect buyers and sellers, facilitate sharing and promote direct trade of assets built on peer trust [

19,

49]. P2P activities consist of selling, sharing and crowdsourcing, which emphasize peers or community as the basis for individual-to-individual interaction.

4.3. Access Economy

Rifkin [

16,

58,

59] proposes that when the industrial economy reaches a new stage, consumers could favor the right to use more than ownership as they can obtain the right at a lower cost. Hence, owning the products permanently will no longer be important to some consumers.

In this access-based consumption, “transactions…may be market-mediated but…no transfer of ownership takes place and differ from both ownership and sharing” [

52] (p. 881). Eckhardt and Bardhi [

60] suggest the access economy can provide convenient and cost-effective access to valued resources, flexibility and freedom from ownership obligations. Consumers can have the same experience and pleasure without ownership [

61,

62]. The access economy emphasizes the value of “access over ownership,” “using over owning” and “use rights instead of ownership.”

4.4. Platform Economy

The digital platform economy is rapidly consolidating, facilitated by new technologies such as big data, new algorithms, cloud computing, and applications that enable social and economic activities to be operated efficiently. In much of the literature [

40,

41,

42], the sharing economy is often defined as “digitally connected” economic activities in (re)circulation and (re)distribution of goods or products to increase the utilization of durable assets, to build social connections between strangers [

37,

63], and to realize sales or rentals among individuals [

64,

65]. Digital platforms enable more real-time, precise and dynamic connection of spare capacity [

66].

4.5. The Sharing Economy

Lessig [

67] defines the sharing economy as a non-monetary exchange and reciprocal economic model. In his description, the sharing economy aims to advocate cultural sharing in the context of culture and art rather than physical resources. Heinrichs [

15] (p. 229) suggests the sharing economy as activities in which “individuals exchanging, redistributing, renting, sharing and donating information, goods and talent”. It is an economic model sharing under-utilized assets for monetary or non-monetary benefits [

49]. In a sense, the sharing economy includes the above features, as “an economic activity in which web platforms facilitate peer-to-peer exchanges of diverse types of goods and services” [

68] (p. 1398), and also a “phenomenon as peer to peer sharing of access to under-utilized goods and services, which prioritizes utilization and accessibility over ownership, either for free or for a fee” [

69] (p. 111). It is a mutually beneficial behavior operated increasingly on the internet platform which can produce economic, social and environmental benefits for participants in transaction and sharing [

70,

71].

The sharing economy is comprised of different elements which intertwine and have different emphases: collaborative consumption or the collaborative economy emphasizes people’s collaboration and consumers’ two-sided role; P2P economy or the peer economy focuses on individual-to-individual business models and reflects the community-based economy; the access economy, access-based consumption or rental economy stresses the value of access over ownership; the platform economy, digital economy, the mesh or app economy highlights the important role of technology.

5. Mapping the Sharing Economy

There is no agreement on what the sharing economy exactly is, and it is so difficult for scholars to agree on one common definition. Alternatively, this paper tries to point out an organizing framework consisting of the seven essential elements of the sharing economy, and then describes a conceptual sharing economy model.

5.1. Seven Organizing Essential Elements of the Sharing Economy

Echoing the literature review of conceptions of the sharing economy and similar terminology, scholars further elaborate on the essential elements of the sharing economy. Mair and Reischauer [

46] point out five main components of the sharing economy: various forms of compensation, market, redistribution of and access to resources, individuals, and a digital platform operated by an organization to analyze its operations. Frenken [

1] adds three constituent parts: peer-to-peer exchange or more precisely consumer-to-consumer (C2C) interaction, temporary access either by borrowing or renting and a better use of underutilized physical assets. Curtis and Lehner [

72] propose five properties of the sharing economy for sustainability: ICT-Mediated, non-pecuniary motivation for ownership, temporary access, rivalrous and tangible goods.

Botsman and Rogers [

19] believe that unique features of the sharing economy are the cluster (user groups), idle capacity, shared beliefs, social public resources, grassroots power and the trust between strangers. Among those sharing economy operators, Zipcar’s co-founder Robin Chase [

73] also emphasizes the trust among people as an asset and key factor promoting the sharing economy, apart from harnessing the power of the internet platform.

While there is no universally accepted definition, based on different ways of conceiving the sharing economy and similar activities, as well as deriving the essential elements of the sharing economy, we can summarize several dimensions often associated with the operation of the sharing economy (

Table 2). These are comprised of ownership and usage transfer (access use rights or transfer ownership), shared resources (idle capacity or new resources), length of time (short-term or long-term), business model (P2P/C2C or business-to-consumer (B2C)), channels (internet platforms mediated or offline), pricing regimes (for monetary profit or free exchanges), and goal-orientation (shared value orientation or pure market orientation).

Based on the review of the existing literature, and observing the operation of sharing economy, we argue that the sharing economy should have the following seven elements: access use rights instead of ownership, idle capacity, short term, P2P/C2C, Internet platforms mediated, for monetary profit, and shared value orientation.

5.1.1. Access Use Rights Instead of Ownership

“Access over ownership” or “use rights instead of ownership” is a common phrase describing the sharing economy. The essence of the sharing economy is that of a leasing economy rather than a buying and selling economy. Sharing the use rights to provide others with access to their own private assets without permanent transfer of ownership is in line with the concept of sharing. Buying and selling in the second-hand market incur transferal of ownership as the providers decide to “dispose” of their goods, and hence, will not be considered a form of the sharing economy [

56].

5.1.2. Idle Capacity

While the sharing economy continues to develop, items for sharing are also expanding, including material resources such as cars, food, and clothing and non-material resources such as services, skill, capital, and information [

36]. At the individual level, these include goods, funds, skill, and time. At the enterprise level, these are the inventory and production capacity.

However, no matter what resource is to be shared, an important feature is its current idle capacity, including under-utilized and excessive goods, skill, capital and time [

42]. Upholding the value that “unused is waste”, it is believed that better utilization of idle capacity through sharing can maximize their utility and benefit the environment and sustainability. In that manner, the sharing economy is about the redistribution of the existing idle resources, rather than the production of a new one.

5.1.3. Short Term

In the sharing economy, the length of time of accessing idle capacity’s use rights can be divided into short-term access and long-term access. Long-term access, in months or even years, is more applicable to material resources such as products or houses. In contrast, short-term access means that the resources used by others are within a short period, even as short as a few hours or minutes [

56]. Comparatively speaking, short-term access might have better resource utilization by satisfying more consumers within a specific period, which is in line with the sharing economy’s objectives of reducing waste and promoting sustainable development.

5.1.4. Peer to Peer

There are many business models such as P2P, consumer-to-consumer (C2C), business-to-consumer (B2C), and even business-to-business (B2B) [

9,

72]. However, the business model of the sharing economy is often operated in a P2P or C2C mode which is a decentralized two-sided market. The essential participants are a massive number of peers playing the roles of demanders/receivers and suppliers/providers. In P2P or C2C economic models, suppliers and providers can offer access to their goods for other consumers’ consumption, which is different from the traditional B2C economic model where companies act as agents to sell their resources to consumers [

74].

5.1.5. Internet Platforms Mediated

In theory, the sharing economy can be operated without internet technology, but it is well accepted that the presence of this technology certainly has benefited its rapid development. In the past, offline sharing generally occurred among trusted and connected acquaintances, mainly for reciprocal and free exchange [

1,

27,

75]. In most cases, it is on a small scale and confined to proximate communities.

The “new” sharing economy uses technology integrating all kinds of information of scattered resources and diversified needs to facilitate the efficient mediation between a massive number of suppliers and demanders around the world, who do not have prior personal connections [

14,

57,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83]. The rapid development of modern information technology and its innovative applications, especially the use of smartphones, broadband, cloud computing, big data, the Internet of things, cashless payment systems, and location-based services, make the sharing economy accessible to more and more parties [

63,

84]. Consumers can place orders online through smartphones and experience them offline, thus connecting the online and offline world. Heavily relying on the Internet, the sharing economy is mainly a web market operated by individuals but increasingly by enterprises [

46]. As facilitator, these organizations operate efficient platforms and charge a fee for every transaction to sustain the platforms and the enterprises [

1].

5.1.6. For Monetary Profit

Of course, the sharing economy can span the continuum covering both the profit-making market economy and the free exchange type gift economy [

85]. People participate in the sharing economy with economic, social, and moral motivation with compensation or other forms of return and satisfaction [

36,

72]. The sharing economy is for “profit” though it can have other returns.

When the sharing economy emerged in the 2000s at a time when the global economy faced uncertainty, participants got involved mainly due to economic need [

55,

86,

87]. The providers could generate additional income, and the receivers could usually access the goods or services at a lower cost [

10,

88,

89,

90]. This is a win–win economic activity that benefits the provider and the receiver.

With an increasing emphasis on monetary reward, the moral threshold for participation in sharing activities might retreat. Sharing activities go beyond reciprocity within small communities to a major form of public economic activities. It is no longer an activity limited to a few people, but an economic activity in which many people can participate [

91].

5.1.7. Shared Value Orientation

However significant the economic motive, social and moral values still have their position in the sharing economy [

21]. These values, as reflected in many examples, include demonstrating care for others, trust in strangers, connecting peoples within and beyond communities, achieving public interests, and promoting green and sustainable development. Shared value orientation is sharing for others, for the society and for the environment.

Although some scholars believed that the consumers are without altruistic motives to participate in the sharing economy and the shared value is less relevant to them [

61,

92,

93], the sharing economy really facilitates sustainable consumption. Consumers indeed have access to sustainable resources or services even if they are not intentional [

94]. As long as it has, perhaps unintentionally, a sustainable effect, it should be included in our ways of understanding the sharing economy.

The sharing economy emphasizes that “unused is waste”, “access over ownership” and “utilization of underutilized resources.” All of these tenets show concern for the environment. With the continuous circulation of resources, the sharing economy can promote better use of underutilized assets [

1]. Thus, the sharing economy may reduce the waste of resources [

76,

81], energy consumption [

95,

96], and greenhouse gas emissions [

97], thereby improving the climate and environment [

98,

99]. These underlying values distinguish the sharing economy from a conventional market economy.

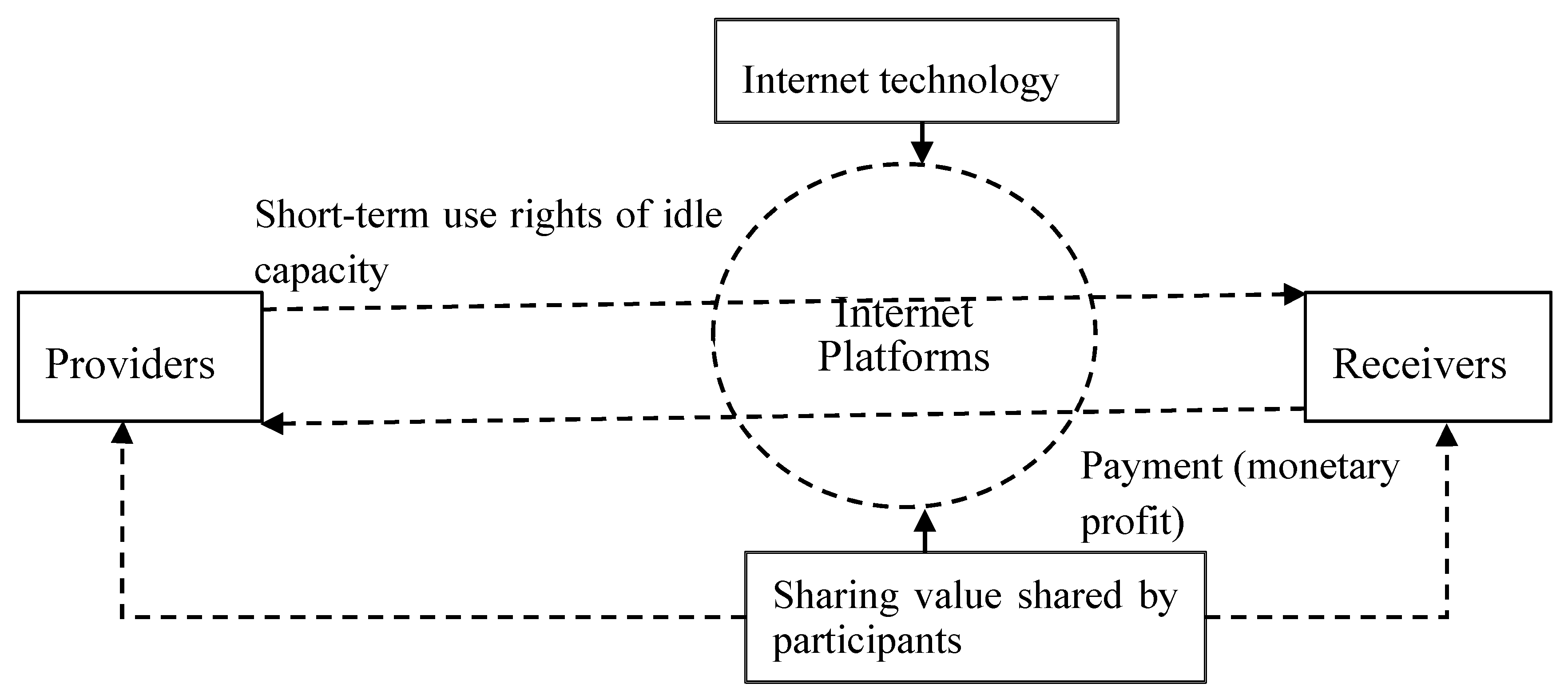

5.2. The Sharing Economy Model

Reviewing the origins and existing conceptual discussion of the sharing economy, this paper argues for seven organizing essential elements for a business to be qualified as sharing economy: access use rights instead of ownership, idle capacity, short term, P2P, Internet platforms mediated, for monetary profit, and shared value orientation. With these essential elements in mind, the sharing economy is a new economic model using the efficient matching of internet platforms with advanced technology, which enables numerous providers to share the short-term use rights of idle capacity with numerous receivers and obtain monetary profit while achieving the optimal allocation of social resources with the value of sharing and sustainability at the same time (

Figure 2).

6. Definition of the Sharing Economy in China

The sharing economy has received great academic interest in China, and efforts have been made to define the term in recent years. For example, Song and Wang [

100] point out that the sharing economy is a method of organizing economic activities characterized by sharing the through wide application of internet technology. Ma [

101] believes that the sharing economy refers to individuals or institutions that share idle resources or services for profit making, and the demanders create value for the environment by using the resources.

Similarly, Dong [

102] suggests that the sharing economy is an economic model using the internet platform to reintegrate, share and reuse idle social resources. Wang [

103] shares this line of thought and proposes that the sharing economy is a resource recycling model with extensive social accessibility that uses the internet platform as an intermediary to improve the social utilization of idle resources (based on P2P, such as shared accommodation), or reduce the potential resource idle rate (based on B2C, such as shared bicycles) through economic or charitable means. These scholars have approached different dimensions of the sharing economy, including its integration with internet technology and online platforms, the nature of resources to be shared and motivation of sharing.

In February 2016, the State Information Center of the People’s Republic of China published the report

Sharing Economy Development Report in China 2016. It refers to the sharing economy as “all economic activities that use modern internet information technology and integrate and share massive and decentralized idle resources to meet diversified needs” [

84] (p. 5). Subsequently, the State Information Center published the

Sharing Economy Development Report in 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020. While the reports reiterated sharing economy as “all economic activities that use modern information technology such as the Internet and integrate massive and decentralized resources to meet diversified needs,” they also pointed out that “sharing of use rights [is] the main feature” [

5] (p. 5), [

104] (p. 3), [

105] (p. 5), [

106] (p. 5).

This definition is the most authoritative one so far, and it could be used as a starting point to redefine the sharing economy in China. According to the State Information Center’s definition, the sharing economy business could be classified into five types based on the items to be shared:

Product sharing includes cars, equipment, toys, clothing, etc., with representative ride sharing platform companies such as Didi Chuxing, Dida Chuxing, Mobike and Ofo and item sharing platform companies such as Hidian, Jiedian, UUsan and Youchang. Similar establishments overseas include Uber, Lyft and Rent the Runway.

Space sharing consists of housing, office, parking spaces, land, etc., with representative platform companies such as Xiaozhu, Tujia, Mayiduanzu and Zhuomuniao. Similar establishments overseas are Airbnb and WeWork.

Financing sharing includes P2P loans and crowdfunding, with representative platform companies such as Lujinsuo, Renrendai, Zhongchoujia and Jingdong crowdfunding. Similar establishments overseas are Lending Club and Kickstarter.

Knowledge and skills sharing consists of advice-giving, knowledge, ability, experience etc., with representative platform companies such as Zhihu, Zaihang, Zhubajie and Mingyizhudao. Similar establishments overseas include Coursera and Task Rabbit.

Labor sharing refers to those mainly concentrated in the life service industry, with representative platform companies such as Aunt came, Jingdong home, Yunmanman and Eleme. Similar establishments overseas are Delivery Hero and HelloFresh.

7. Limitations of the Definition and its Misuse in China

The State Information Center’s operational definition includes a wide range of economic activities, with classifications that incorporate virtually all economic activities into the label of the sharing economy. This all-inclusive definition over-stretches the boundary and might possibly blur the very essential elements of being a sharing economy. There are four major misuses of the label in China.

7.1. Primacy of Short-Term Use Rights Over Long-Term or Ownership

We agree with the access of use rights as essential to the sharing economy, but there must be a requirement for the length of time one may use the product. Many operations, although they have the label of the sharing economy but involve ownership, such as second-hand market platforms like Zhuanzhuan and Xianyu, will be excluded. While these platforms, as examples of the circular economy, can still achieve reduction of resources, these transactions do not comply with the principle of “access over ownership.”

To count as part of the sharing economy, users may only have short-term access. This could be a few minutes, a few hours, or even as long as a few days. However, it should not be long-term as the longer the access, the closer to ownership, which might reduce the efficiency of use. Therefore, we argue that the sharing economy has to exclude long-term rental sharing practices such as Ziru and Anjuke.

7.2. Sharing Idle Resources Rather than Production of New Resources

The notion that resources to be shared must be idle was removed in the State Information Center’s 2017 report. Based on our above review, we support the notion that idle resources for sharing are one of the essential elements of the sharing economy. Shared resources should be idle and should not be specifically created for sharing. Only sharing idle resources can truly qualify as sharing to be in line with the sharing economy concept of “value unused is waste.”

In reality, in China, there are many examples of this element that the platform operators, suppliers and receivers might simply miss or even ignore; for example, the giant sharing bicycles and car operators, (e.g., Ofo and Mobike; DiDi Premier), sharing mobile power banks (e.g., Hidian and Jiedian), sharing umbrellas (e.g., UUsan), and sharing KTV (e.g., Youchang). Reviewing their business model, none of them can be considered part of the real sharing economy because the resources they share are not idle, but newly produced. These businesses have not only failed to achieve better utilization of existing resources, but in turn, contribute to the waste of resources. As reported, more than 20 million sharing bicycles were put on the market in 2017, and it is expected that 300,000 tons of scrap metal will be generated when they are scrapped [

107].

7.3. P2P or C2C Rather Than B2C or C2B2C

P2P or C2C is one of the core elements of the sharing economy. It is a direct transaction of idle resources from peer to peer or from consumer to consumer. Internet platforms only provide technical support for the connection between the supply and demand sides and should not participate in the transaction. On the other hand, B2C is usually a traditional business model in which a company sells their goods to individual consumers. According to the current definition of the sharing economy in China, the business model of many sharing platforms is not P2P but B2C; for example, sharing bicycles (e.g., Ofo and Mobike) and sharing mobile power banks (e.g., Hidian and Jiedian), in which the bicycles and mobile power banks are actually company assets, or even produced by them in collaboration with the upstream industrial chain. The vehicles of DiDi Premier belong to its own platform—Didi Chuxing; and drivers of DiDi Premier are also full-time workers directly hired by Didi Chuxing. This is a typical B2C business model.

In China, there is another C2B2C business model that further complicates the scene. In this mode, the business will integrate resources from individual providers through long-term renting (or even acquisition), and then sublets them to individual receivers; with contracts concluded with both providers and receivers. From this perspective, such resources for sharing could be the companies’ “heavy assets”. For example, Tujia and Zhubaijia have taken up the management of a large number of properties after signing contracts with their owners and lease these properties to individual tenants. It is clear that both B2C and C2B2C models do not follow the principle of P2P or C2C, and in that sense, they do not possess this essential element of the sharing economy.

7.4. Primacy of “Sharing” Over Technology and Business

The uniqueness of the sharing economy lies in “sharing”. However, many sharing economy operations in China, in fact, do not emphasize “sharing,” but brand themselves by technology, business scale and return. This element was also not included in the State Information Center’s definition. While we may be fascinated by the application of advanced internet technology to achieve such a phenomenal scale of business, we should not lose sight of the essential values promoting sustainable development and “use over own.” However, neither the current definitions nor the usage of the term “sharing economy” in many business operations in China reveal or reflect such value pursuits.

Even though some businesses claim to embrace and promote such values in their mission statements, the intended outcomes have failed to materialize and instead, the results have been counterproductive. For example, the intentions of “sharing” bicycles to maximize utilization of (though not idle) resources are good and worthy of support. Regrettably, the result is that these business cause huge waste of resources as most bicycles are disposed of. By 2020, nearly 10 million sharing bicycles had been scrapped [

108]. Without truly embracing the values of the sharing economy, these operations are simply misusing the label for their own interests.

8. Classifying the Sharing Economy in China

We have reviewed the explosive growth of the sharing economy in China, but at the same time, have discovered that a number of businesses are actually not part of the sharing economy as we have mapped, but have misused the label for their own interests. There is an obvious need to demystify and classify sharing economy businesses in China for any meaningful and focused study.

About the classification of the sharing economy, Habibi et al. [

109] point out a continuum between “pure sharing” (such as nonreciprocal, social links, money irrelevant) and “pure exchange” (such as reciprocal, balanced exchange, monetary) in non-ownership collaborative consumption. Ertz et al. [

56] also propose three continuums of the collaborate consumption ranging from free to monetized, mutualization to redistribution, and pure offline to pure online. Modeling on these ways of conceptualization, and following the seven organizing essential elements or dimensions of the sharing economy we argued, three categories of sharing economy operations are proposed: sharing economy, quasi-sharing economy and pseudo-sharing economy. These are divided by their compliance with all or some of the seven organizing essential elements (

Table 3).

Category 1: Sharing economy

We propose that only those businesses satisfying all seven elements can be considered part of the sharing economy: (1) sharing access use rights rather than ownership; (2) resources to be shared are idle and not newly created for this “sharing”; (3) sharing short-term use rights of idle resources rather than long-term access; (4) business model of P2P or C2C, which is a “direct” transaction between providers and receivers mediated by self-owned platforms or those provided by others, rather than a business model of B2C (i.e., companies providing products or services to consumers); (5) internet platforms (increasingly mobile ones) adopting information technology serving as an intermediary for efficient matching and transactions between providers and receivers; (6) transactions usually involve monetary profit; (7) relevant to the values underlying the sharing economy and shared by participants. In China, the representative platforms include DiDi Hitch, DiDi Express, and Xiaozhu.

Category 2: Quasi-sharing economy

The quasi-sharing economy has most of the elements but differs from the sharing economy in subtle ways. Based on the current operation in China, we can further divide those businesses in this category into three main types: B2C short-term renting, C2B2C short-term renting and long-term renting. While the missing elements are not very visible to the public, differentiating these from the sharing economy is difficult, and public misconception is not uncommon.

B2C short-term renting: This is a short-term rental economy, but it does not meet the elements of idle resources and the P2P or C2C business model of the sharing economy. The shared resources are newly and specially created by the business itself. The best examples would be the once popular but declining bicycle sharing businesses (e.g., Ofo and Mobike) and DiDi Premier as the cars are owned by the company and the drivers are directly hired.

C2B2C short-term renting: While operating as a B2C short-term rental economy, it differs from the former in that the resources shared are existing idle resources. However, in contrast to the sharing economy, these scattered idle resources are rented or purchased by the business who owned the platform first and then temporarily leased to consumers. In this way, the platform possesses heavy assets rather than just providing technical support for efficient matching between the supply and demand sides. Tujia and Zhubaijia are representative cases; they operate by integrating (and even upgrading) scattered housing resources through leasing or purchase and then renting them to consumers.

Long-term renting: This category differs from sharing economy in the time dimension. We argue that short-term sharing is an essential element of the sharing economy, as long-term renting significantly reduces resource utilization, which contradicts the objectives of maximizing utility through sharing. This type of business is essentially the traditional leasing economy in the property leasing business, but with better use of internet technology. For example, Ziru and Anjuke are popular long-term rental housing platforms, with most of their listed properties either rented from owners or owned by platforms.

Category 3: Pseudo-sharing economy

This category is not part of the sharing economy at all but still uses the label for various reasons. It can be subdivided into two types as observed in the market: the second-hand market and fake sharing.

The Second-hand market: The essence of the sharing economy is a leasing economy. This type does not comply with the essential elements of “use rights instead of ownership” and directly exchanges ownership of idle resources (i.e., buying and selling second-hand items). In this market, the operation can also use a C2B2C trading model: second-hand goods platforms in which platform operators purchase second-hand resources first from providers and then sell them to consumers. This kind of transaction can be processed through both offline (e.g., in flea markets) and online. Representative cases of this type are Zhuanzhuan and Xianyu.

Fake sharing: This type of operation can be conducted in both offline or online environments and in B2C or P2P formats. This type cannot be included in the sharing economy because it does not follow the values underlying the sharing economy. For example, the activities of sharing girlfriends or boyfriends is not the sharing economy because the resources to be shared are not objects, not knowledge, and not skills, but the affection of living humans, and such transactions are controversial. It can be considered business hype disguised as the sharing economy.

9. Conclusions and Discussion

In the process of the explosive growth of the sharing economy, especially in China, different scholars and the government have proposed various definitions with different focuses. The variety of definitions are mostly so broad that they cannot differentiate the sharing economy from other forms of economic activities, such as the gift economy, the traditional B2C economy, the leasing economy and the platform economy. In order to critically examine the essential elements of the sharing economy to provide a sound basis for any meaningful discussion and investigation, this paper argues for the following seven elements for the sharing economy: access use rights instead of ownership, idle capacity, short term, P2P, internet platforms mediated, for monetary profit and shared value orientation. We propose that only those economic activities that satisfy all these elements can be considered part of the sharing economy. This narrower mapping certainly limits the scope of the sharing economy but can better differentiate itself from misuse of the label.

This attempt is crucial in China as we found that even the authoritative definition still has its limitations—excessive focus on the technical side and economic benefits that neglects the nature of resources to be shared, the platform, and the underlying values to be shared. We have described the rather confusing situation in China where numerous leading and emerging businesses are using the label of the sharing economy. We propose seven organizing essential elements to differentiate the sharing economy from others. As clarified above, many of them are simply cases of quasi- or pseudo-sharing economy.

We adopt a narrower mapping of the sharing economy: it is an economic model facilitated by efficient matching through internet platforms adopting internet information technology, with numerous providers that temporarily share the use rights of idle capacity with numerous receivers, gain monetary profit, achieve the optimal allocation of social resources and promote the underlying social values. Guided by this model, we seek to distinguish the sharing economy from the quasi- and pseudo-sharing economy, which can help the government to formulate more appropriate policies for the sharing economy. By focusing on the sharing economy, the government, investors, providers or receivers can be more targeting in their investment and engagement. By engaging in sharing economy activities, we can achieve a better result of promoting its values, highlighting the role of individuals and reducing monopoly, reducing wastage, and returning to the value of sharing and promoting social connection and sustainability. Supported by concrete examples, we have provided a clear organizing framework and typologies for better understanding of the sharing economy in China and other countries.

Focusing on the real sharing economic sector, we can further discuss the problems facing it. From the perspective of government, the first problem will be lag in policy and the vacuum that results. In China, the rapid development of the sharing economy always precedes the formulation and implementation of policies although the government has stepped up its efforts in this aspect, with relevant policies in place facilitating a healthier development of the sharing economy. Secondly, there are problems related to policy implementation as different regions apply their own interpretations and rules, which complicate the operation of business.

The sharing economy operators have to pay attention to the quality of services and the assumed core values of the sharing economy while remaining competitive in the market. It is predicted that only a few mega platforms could survive this process of fierce competition. Without losing sight of the essential elements, including the values, maintaining a high quality service standard is also a challenge. For example, ensuring the safety of DiDi passengers and drivers, apart from personal information security, has raised grave concern. Building trust between providers and receivers as well as platform operators is increasingly difficult.

Receivers have also reported that the kind of personal touch in the sharing process has gradually diminished as more and more resources providers become full-time participants. For example, DiDi Express drivers are increasingly full-time drivers, and more professional landlords are emerging. These compromise the nature of the sharing economy.

These challenges require continuous and coordinated efforts from all sectors to further improve the technology, regulation and operation of the sharing economy while maintaining its essential elements. We also need to have better understanding of the participants, especially of their motivations for participation. While the economy can be further developed, sharing should not be compromised.