Sustainability in Tourism as an Innovation Driver: An Analysis of Family Business Reality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

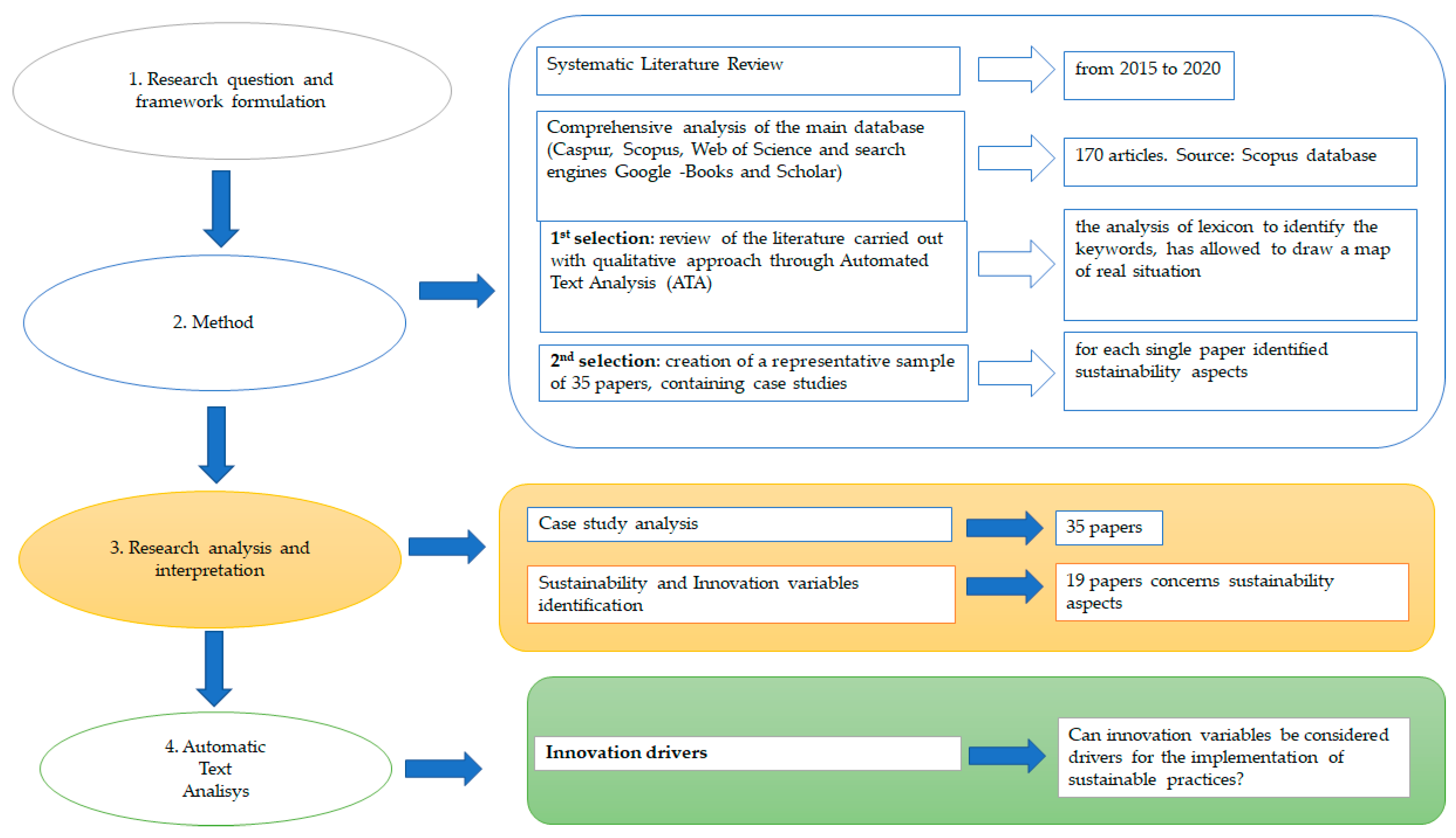

3. Methodology

4. Findings

Empirical Evidence

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Limits and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Del Carmen Canizares Ruiz, M. Sustainability and tourism: From international documentation to planning in Spain «horizon 2020» [Sostenibilidad y turismo: De la documentación internacional a la planificación en España «horizonte 2020»]. Boletín Asociación Geógrafos Españoles 2013, 61, 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga, Y.; Espinoza, R.; Zuñiga, X.; Espinoza, E.; Villegas, F.; Campos, H. Alternativa Para el Desarrollo Sostenible del Turismo en el Cantón Milagro (Ecuador): Viveros, los Nuevos Emprendimientos. Espacios 2018, 39, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review|Le tourisme durable: Un état de la question. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Culasso, F.; Truant, E. Unlocking value creation using an agritourism business model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J. Family business in tourism. State of the art. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J. Characteristics and goals of family and owner-operated businesses in the rural tourism and hospitality sectors. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Peters, M. Innovativeness and control mechanisms in tourism and hospitality family firms: A comparative study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 70, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legohérel, P.; Callot, P.; Gallopel, K.; Peters, M. Personality Characteristics, Attitude Toward Risk, and Decisional Orientation of the Small Business Entrepreneur: A Study of Hospitality Managers. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2004, 28, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Frehse, J.; Buhalis, D. The importance of lifestyle entrepreneurship: A conceptual study of the tourism industry. (Special issue: Innovation and entrepreneurship in the tourism industry). PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2009, 7, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J.; Sharma, P. Defining the Family Business by Behavior. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 23, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, H.N.; Mohd Puzi, M.A.; Banki, M.B.; Yusoff, N. Inherent factors of family business and transgenerational influencing tourism business in Malaysian islands. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2019, 17, 624–641. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, L.; Tucci, L.C. Chapter 21: Business Model Innovation. In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Valeri, M.; Baggio, R. Italian tourism intermediaries: A social network analysis exploration. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Rockström, J.; Raskin, P.; Scoones, I.; Stirling, A.C.; Smith, A.; Thompson, J.; Millstone, E.; Ely, A.; Arond, E.; et al. Transforming innovation for sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, N.; Jorna, R.; Van Engelen, J.O. The sustainability of “sustainability”—A study into the conceptual foundations of the notion of “sustainability”. In Tools, Techniques and Approaches for Sustainability: Collected Writings in Environmental Assessment Policy and Management; World Scientific Publishing Company: Sinapore, 2010; pp. 337–369. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Dessant, J.; Overy, P.; Denyer, D. Innovating for Sustainability. 2012. Available online: https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10036/4105/Adams%202012-%20NBS%20Systematic%20Review%20Innovation.pdf?sequence=8 (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Schaltegger, S.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Hansen, E.G. Business cases for sustainability: The role of business model innovation for corporate sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolink, A.; Niesten, E. Sustainable Development and Business Models of Entrepreneurs in the Organic Food Industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Vladimirova, D.; Holgado, M.; Van Fossen, K.; Yang, M.; Silva, E.A.; Barlow, C.Y. Business Model Innovation for Sustainability: Towards a Unified Perspective for Creation of Sustainable Business Models. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuščer, K.; Mihalič, T.; Pechlaner, H. Innovation, sustainable tourism and environments in mountain destination development: A comparative analysis of Austria, Slovenia and Switzerland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.W.; Cheng, J.S. Exploring driving forces of innovation in the MSEs: The case of the sustainable B & B tourism industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Management; CABI: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.M.M.; Tseng, C.Y.; Chen, L.C. Choosing between exiting or innovative solutions for bed and breakfasts. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, J.; Prügl, R. Innovation activities during intra-family leadership succession in family firms: An empirical study from a socioemotional wealth perspective. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2015, 6, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Elston, J.A. Entrepreneurial motives and characteristics: An analysis of small restaurant owners. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 23, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Pizzurno, E.; Cassia, L. Product innovation in family versus nonfamily firms: An exploratory analysis. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Kallmuenzer, A. Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: The case of the hospitality industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermanns, F.W.; Eddleston, K.A.; Sarathy, R.; Murphy, F. Innovativeness in family firms: A family influence perspective. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 38, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbershon, T.G.; Pistrui, J. Enterprising Families Domain: Family-Influenced Ownership Groups in Pursuit of Transgenerational Wealth. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 15, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; Nordqvist, M. Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: A generational perspective. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 38, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms: Theoretical Dimensions, Assessment Approaches, and Agenda for Future Research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton-Miller, I.; Miller, D. Family firms and practices of sustainability: A contingency view. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2016, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Nikolakis, W.; Peters, M.; Zanon, J. Trade-offs between dimensions of sustainability: Exploratory evidence from family firms in rural tourism regions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1204–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Henriques, I. Stakeholder influences on sustainability practices in the Canadian forest products industry. Strategy Manag. J. 2005, 26, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memili, E.; Fang, H.C.; Koç, B.; Yildirim-Öktem, Ö.; Sonmez, S. Sustainability practices of family firms: The interplay between family ownership and long-term orientation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banki, M.B.; Ismail, H.N.; Muhammad, I.B. Coping with seasonality: A case study of family owned micro tourism businesses in Obudu Mountain Resort in Nigeria. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A.; Sirmon, D.G. A model of strategic enterpreneurship: The construct and its dimensions. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 963–989. [Google Scholar]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A. Managing Resources: Linking Unique Resources, Management, and Wealth Creation in Family Firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 27, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowka, G.; Zehrer, A. Tourism family-business owners’ risk perception: Its impact on destination development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Watanabe, C. Innovation Ecosystem for Sustainable Development. In Sustainable Development—Policy and Urban Development—Tourism, Life Science, Management and Environment; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. The Entrepreneurial Clarifying It Construct and Linking Orientation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 16, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundbo, J.; Orfila-Sintes, F.; Sørensen, F. The innovative behaviour of tourism firms-Comparative studies of Denmark and Spain. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassia, L.; De Massis, A.; Pizzurno, E. An exploratory investigation on NPD in Small Family Businesses from Northern Italy. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Classen, N.; Van Gils, A.; Bammens, Y.; Carree, M. Accessing Resources from Innovation Partners: The Search Breadth of Family SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2012, 50, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Williams, A.M. Tourism and Innovation; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 0203938437. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalager, A.M. A review of innovation research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.; Tintoré, J.; Aguiló, E.; Bravo, A.; Mulet, J. Innovation in the tourism sector: Results from a pilot study in the Balearic Islands. Tour. Econ. 2003, 9, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B. Innovation in Small and Medium-Sized Tourism Enterprises in Tyrol, Austria. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2008, 9, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottenbacher, M.; Gnoth, J. How to develop successful hospitality innovation. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2005, 46, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Williams, A. Knowledge transfer and management in tourism organisations: An emerging research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves, J.; Diaz-Meneses, G. Antecedents and outcomes of marketing innovation: An empirical analysis in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1554–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Shin, W.J. Marketing tradition-bound products through storytelling: A case study of a Japanese sake brewery. Serv. Bus. 2015, 9, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M.; Baggio, R. A critical reflection on the adoption of blockchain in tourism. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L. Tourists’ perceptions of environmentally responsible innovations at tourism businesses. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M.; Baggio, R. Social network analysis: Organizational implications in tourism management. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, K.S.; Chua, B.L.; Han, H. Independent café entrepreneurships in Klang Valley, Malaysia—Challenges and critical factors for success: Does family matter? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergfeld, M.M.H.; Weber, F.M. Dynasties of innovation: Highly performing German family firms and the owners’ role for innovation. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2011, 13, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitcharoen, K. The Importance-Performance Analysis of service quality in administrative departments of private universities in Thailand. ABAC J. 2004, 24, 20–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hamed, S. Habiba Community: Brand management for a family business. Emerald. Emerg. Mark. Case Stud. 2019, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, O. Factors impacting airline efficiency in southern Africa: A data envelopment analysis. GeoJournal 2019, 84, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertuna, B.; Karatas-Ozkan, M.; Yamak, S. Diffusion of sustainability and CSR discourse in hospitality industry: Dynamics of local context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2564–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelo, E.; Casalegno, C.; Civera, C.; Büchi, G. A Ticket to Coffee: Stakeholder View and Theoretical Framework of Coffee Tourism Benefits. Tour. Anal. 2019, 24, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saganeiti, L.; Pilogallo, A.; Izzo, C.; Piro, R.; Scorza, F.; Murgante, B. Development Strategies of Agro-Food Sector in Basilicata Region (Italy): Evidence from INNOVAGRO Project; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, M. Humanism and business: The case of a sustainable business experience in the Florentine tourist sector based on the civil economy tradition. In Sustainability and the Humanities; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-319-95336-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mustapha, M.; Awang, K.W. Sustainability of a beach resort: A case study. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga Estrella, Y.M.; Espinoza Toalombo, R.A.; Zuñiga Santillán, X.L.; Espinoza Solís, E.J.; Villegas Yagual, F.E.; Campos Rocafuerte, H.F. Tourism start-ups; an alternative for the development of sustainable tourism in Milagro city: Plant nurseries, an entrepreneurial opportunity. Revista Espacios 2018, 39, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Rubio-Andrada, L.; Pedroche, M.S.C. Collaborative economy. An approach to sharing tourism in Spain. Rev. Econ. Publica, Soc. y Coop. 2016, 88, 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- Banki, M.B.; Ismail, H.N. Understanding the characteristics of family owned tourism micro businesses in mountain destinations in developing countries: Evidence from Nigeria. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 13, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, K.; Suchet-Pearson, S.; Wright, S.; Tofa, M.; Rowland, C.; Burarrwanga, L.; Ganambarr, R.; Ganambarr, M.; Ganambarr, B.; Maymuru, D. Transforming tourists and “culturalising commerce”: Indigenous tourism at Bawaka in Northern Australia. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

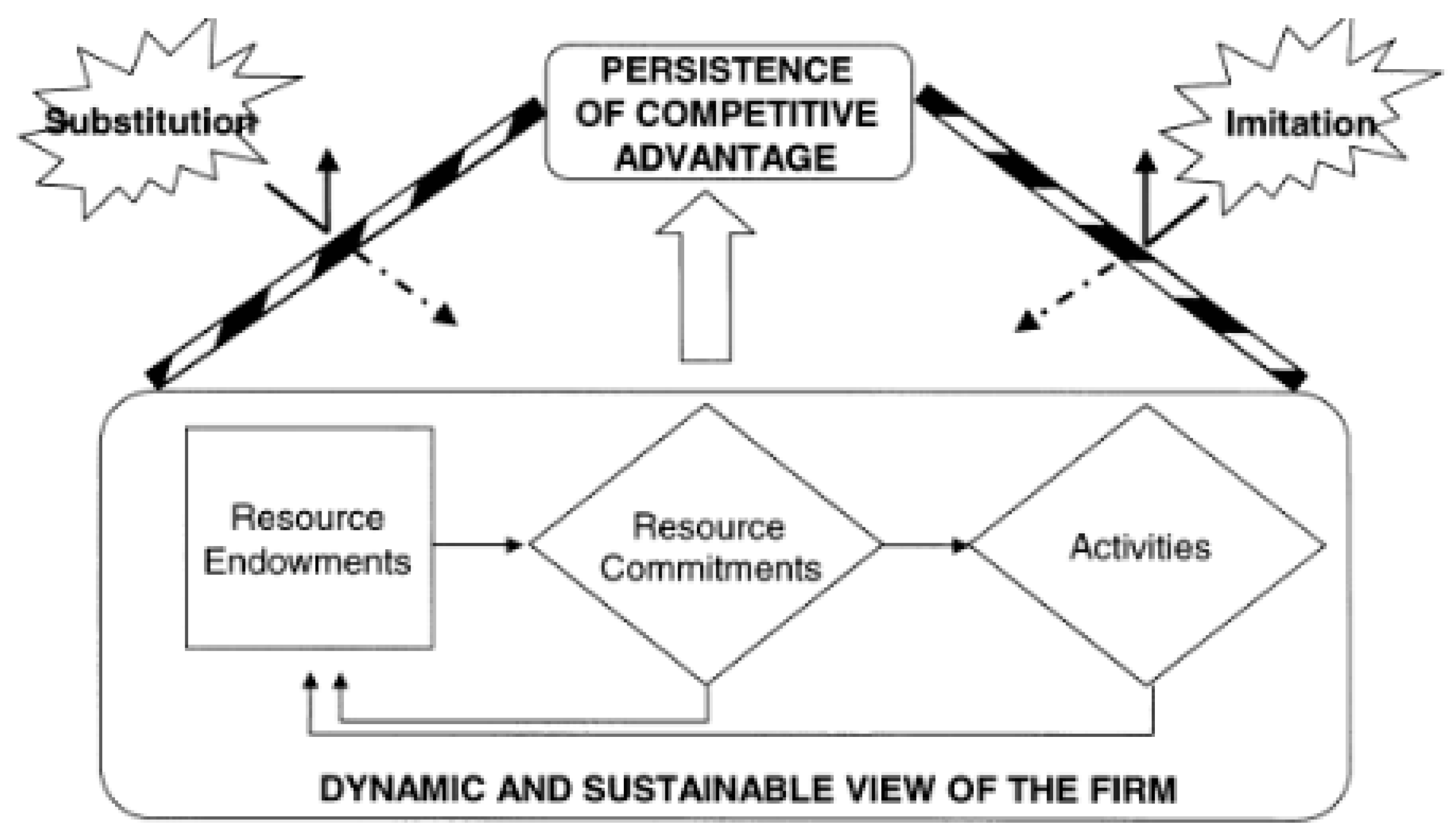

- Rodriguez, M.A.; Ricart, J.E.; Sanchez, P. Sustainable development and the sustainability of competitive advantage: A dynamic and sustainable view of the firm. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2002, 11, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcese, G.; Flammini, S.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Martucci, O. Evidence and experience of open sustainability innovation practices in the food sector. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8067–8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabphet, S.; Scott, N.; Ruhanen, L. Applying diffusion theory to destination stakeholder understanding of sustainable tourism development: A case from Thailand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 1107–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.B.L.; Moores, K. A 10-year longitudinal investigation of strategy, systems, and environment on innovation in family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2006, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Brigham, K.H.; Moss, T.W. Long-term orientation: Implications for the entrepreneurial orientation and performance of family businesses. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlar, J.; De Massis, A. Goal setting in family firms: Goal diversity, social interactions, and collective commitment to family-centered goals. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 1263–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskiewicz, P.; Combs, J.G.; Rau, S.B. Entrepreneurial legacy: Toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, C. Predictors of Entrepreneurship in Family Firms. J. Priv. Equity 2004, 7, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Cliff, J.E. The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, W.C. The Succession Experience of the Next Generation. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1992, 5, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermanns, F.W.; Eddleston, K.A.; Barnett, T.; Pearson, A. An exploratory study of family member characteristics and involvement: Effects on entrepreneurial behavior in the family firm. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepner, E. The Family and the Firm: A Coevolutionary Perspective. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1991, 4, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Suárez, K.; De Saá-Pérez, P.; García-Almeida, D. The Succession Process from a Resource- and Knowledge-Based View of the Family Firm. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2001, 14, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.M. Impacts of the Tourist Activity and Citizens’ Evaluation About the Necessity for Resting Periods. In Strategic Perspectives in Destination Marketing; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 81–112. ISBN 9781522558354. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, M.A.; Haynes, G.W.; Schrank, H.L.; Danes, S.M. Socially Responsible Processes of Small Family Business Owners. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 48, 524–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, D.; Hall, C.M.; Stoeckl, N. The resilience of formal and informal tourism enterprises to disasters: Reef tourism in Phuket, Thailand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 645–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Article | Year | Key Aspects | Sustainability Variables | Innovation Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glowka, G., Zehrer, A. [40] | Tourism family-business owners’ risk perception: Its impact on destination development | 2019 | Theory of the parties and sustainable development: stakeholder’s satisfaction and risks insurance of destination | x | |

| Hamed, S. [61] | Habiba Community: brand management for a family business | 2019 | Eco-branding in the tourism sector | x | |

| Ismail, H.N., MohdPuzi, M.A., Banki, M.B., Yusoff, N. [12] | Inherent factors of family business and transgenerational influencing tourism business in Malaysian islands | 2019 | Resilient factors for sustainability of long-term tourism development. | x | |

| Mhlanga, O. [62] | Factors impacting airline efficiency in southern Africa: a data envelopment analysis | 2019 | Regions’ potential for tourism growth and regional sustainability. | x | |

| Ertuna, B., Karatas-Ozkan, M., Yamak, S. [63] | Diffusion of sustainability and CSR discourse in hospitality industry: Dynamics of local context | 2019 | CSR in the collaboration of multinational companies with local hotels in developing countries. | x | |

| Candelo, E., Casalegno, C., Civera, C., Büchi, G. [64] | A ticket to coffee: Stakeholder view and theoretical framework of coffee tourism benefits | 2019 | Sustainability of coffee tourism development | x | |

| Saganeiti, L., Pilogallo, A., Izzo, C., Piro, R., Scorza, F. [65] | Development Strategies of Agro-Food Sector in Basilicata Region (Italy): Evidence from INNOVAGRO Project | 2019 | Intraregional approach for agri-food promotion of environmentally friendly agricultural practices | x | x |

| Liu, C.-W., Cheng, J.-S. [22] | Exploring driving forces of innovation in the MSEs: The case of the sustainable B & B tourism industry | 2018 | Drivers support innovations and sustainable development | x | x |

| Tortora, M. [66] | Humanism and business: The case of a sustainable business experience in the Florentine tourist sector based on the civil economy tradition | 2018 | Sustainable tourism experience through the humanities | x | x |

| Kallmuenzer, A., Nikolakis, W., Peters, M., Zanon, J. [34] | Trade-offs between dimensions of sustainability: exploratory evidence from family firms in rural tourism regions | 2018 | Sustainability in rural tourism family businesses (RTFF) | x | |

| Kuo, C.-M.M., Tseng, C.-Y., Chen, L.-C. [24] | Choosing between exiting or innovative solutions for bed and breakfasts | 2018 | Innovative solutions for the sustainability of their B&B | x | x |

| Memili, E., Fang, H.C., Koç, B., Yildirim-Öktem, Ö., Sonmez, S. [36] | Sustainability practices of family firms: the interplay between family ownership and long-term orientation | 2018 | Relationship between sustainability practices and business continuity | x | |

| Mustapha, M., Awang, K.W. [67] | Sustainability of a beach resort: A case study | 2018 | Analysis of the performance of a resort for sustainability insurance of the beach | x | |

| Arteaga Estrella, Y.M., Espinoza Toalombo, R.A., ZuñigaSantillán, X.L., Espinoza Solís, E.J., VillegasYagual, F.E., Campos [68] | Tourism start-ups; an alternative for the development of sustainable tourism in Milagro city: Plant nurseries, an entrepreneurial opportunity | 2018 | Relationship between tourism start-ups and sustainable tourism | x | x |

| Broccardo, L., Culasso, F., Truant, E. [5] | Unlocking value creation using an agritourism business model | 2017 | Success factors of the Italian farm business model considering sustainability variables | x | x |

| Banki, M.B., Ismail, H.N., Muhammad, I.B. [37] | Coping with seasonality: A case study of family owned micro tourism businesses in Obudu Mountain Resort in Nigeria | 2016 | Effects of seasonality on the survival and sustainability of tourism businesses | x | |

| Rodríguez-Antón, J.M., Alonso-Almeida, M.M., Rubio-Andrada, L., Pedroche, M.S.C. [69] | Collaborative economy. An approach to sharing tourism in Spain | 2016 | Sharing economy in tourism | x | x |

| Banki, M.B., Ismail, H.N. [70] | Understanding the characteristics of family owned tourism micro businesses in mountain destinations in developing countries: Evidence from Nigeria | 2015 | Long-term sustainability and succession planning | x | |

| Lloyd, K., Suchet-Pearson, S., Wright, S., Tofa, M., Rowland, C., Burarrwanga, L., Ganambarr, R., Ganambarr, M., Ganambarr, B., Maymuru, D. [71] | Transforming tourists and “culturalising commerce”: Indigenous tourism at Bawaka in Northern Australia | 2015 | Indigenous tourism as a means of economic growth and development | x |

| Authors | Variables and Drivers for Sustainability |

|---|---|

| Glowka and Zehrer (2019) [40] | Glowka and Zehrer (2019) applying the “theory of the parts” to the development of sustainable tourism, identify the incorporation of the needs of the stakeholders in the objectives and in the corporate vision as a means of ensuring sustainability in the company. |

| Hamed, S. [61] | Hamed (2019) highlights how sustainable development can be achieved through the generation of new ideas and trends in the field of marketing and branding: eco-branding and branding of family businesses. |

| Ismail, H.N., MohdPuzi, M.A., Banki, M.B., Yusoff, N. [12] | Ismail et al. (2019) highlight how resilient factors are a determining factor of sustainable development confirming that non-economic factors are an example of family values, the direct involvement of family members in business and corporate conflicts themselves, are crucial in the implementation of sustainable measures that guarantee the long-term survival of the company. |

| Mhlanga, O. [62] | Mhlanga (2019) highlights how an improvement in air performance in southern Africa will lead to an improvement in tourism growth and regional sustainability. |

| Ertuna, B., Karatas-Ozkan, M., Yamak, S. [63] | Ertuna et al. (2019) they aim at identifying the institutional logics that determine CRS and act as sustainability drivers in Turkish tourism companies, and to what extent sustainability practices and CRS align with local institutional logics and needs. |

| Candelo, E., Casalegno, C., Civera, C., Büchi, G. [64] | Candelo et al. (2019) through a case study on Costa Rica on the benefits of coffee tourism on local farmers, they underline how the 4 main advantages for local farming communities are represented by empowerment and cooperation, business diversification, sustainability and the creation of a target image. |

| Saganeiti, L., Pilogallo, A., Izzo, C., Piro, R., Scorza, F. [65] | Saganeiti et al. (2019) through the project “Development of an innovative network for the promotion of extroversion of agro-food companies in Adriatic-Ionian Area” (INNOVAGRO), highlight the need to implement new strategies based on the adoption of ITC technologies combined with the implementation of environmentally friendly agricultural activities. |

| Liu, C.-W., Cheng, J.-S. [22] | Liu and Cheng (2018) identify emerging external and internal factors as key factors of innovation. External factors are represented by customers and in particular by their preferences and needs which represent a guide for the creation of new ideas, therefore customers represent an important source of innovation. Other external sources of innovation are external knowledge and market trends. Regarding internal factors, the results show that the central source of innovation is represented by the lifestyles of the owners, i.e., interests, opinions, attitudes, experiences and context in which they live. |

| Tortora, M. [66] | Tortora (2018) identifies a new approach represented by the possibility of obtaining a sustainable tourist experience in a city of art through the humanities: museums, paintings, statues, the history of some families represent an example of practices of responsibility for society and for the environment itself. |

| Kallmuenzer, A., Nikolakis, W., Peters, M., Zanon, J. [34] | Kallmuenzer et al. (2018) show how in family businesses, particularly in the rural tourism sector, decision-making in terms of sustainability, once economic performance is ensured, is guided by ecological and social aspects and observations. The unique family resources and dynamics and the intergenerational nature of family businesses lead to a greater sensitivity of these companies to the social and ecological dynamics that manifest themselves in the decision-making process. |

| Kuo, C.-M.M., Tseng, C.-Y., Chen, L.-C. [24] | Kuo et al. (2018)underline the importance for sustainability in tourism and in particular in the B&B sector of innovative practices combined with differentiation strategies, especially when the market is saturated or the product is in a phase of decline in its life cycle |

| Memili, E., Fang, H.C., Koç, B., Yildirim-Öktem, Ö., Sonmez, S. [36] | Memili et al. (2018) highlight how the long-term orientation LTO) reduces the negative effects of family ownership by promoting and encouraging the adoption of sustainability practices |

| Mustapha, M., Awang, K.W. [67] | Mustapha et Awang (2018) through a resort on an island in Terengganu, they identify the guarantee of business sustainability in performance management |

| Arteaga Estrella, Y.M., Espinoza Toalombo, R.A., ZuñigaSantillán, X.L., Espinoza Solís, E.J., VillegasYagual, F.E., Campos [68] | Y. Arteaga, R. Espinoza, X. Zuñiga et al. wonder if entrepreneurs are methodical in taking care of the environment, when it comes to meeting the needs of their customers; therefore an analysis of tourism micro-enterprises emerges and their current and future impact in terms of social, economic, environmental factors and in particular on sustainable development. |

| Broccardo, L., Culasso, F., Truant, E. [5] | Broccardo et al. have a new appearance representedby the concept of agro-ecological tourism linked to the concept of tourism which aims to strengthen the link between tourism and agriculture while promoting principles of sustainability |

| Banki, M.B., Ismail, H.N., Muhammad, I.B. [37] | Bancki, Ismail et Muhammad (2016) highlight how seasonality in tourism plays an important role and has significant effects on the survival and sustainability of tourism businesses |

| Rodríguez-Antón, J.M., Alonso-Almeida, M.M., Rubio-Andrada, L., Pedroche, M.S.C. [69] | Rodríguez-Antón et al. (2016) highlight how in many economic sectors but in particular in the traditional tourism sector as well as in the housing and transport sub-sectors, a new economic model is becoming increasingly important. and social: the collaborative economy. This model is based on the temporary sharing of goods and services in exchange for money or other services by online platforms. In relation to this work, with a view to sustainability, the European Economic and Social Committee, through an opinion issued in 2014, defined the “Collaborative or participatory consumption: a sustainability model for the 21st century”. |

| Banki, M.B., Ismail, H.N. [70] | Banki et Ismail (2015) stress that a lack of succession planning in family tourism businesses can have an impact on sustainability |

| Lloyd, K., Suchet-Pearson, S., Wright, S., Tofa, M., Rowland, C., Burarrwanga, L., Ganambarr, R., Ganambarr, M., Ganambarr, B., Maymuru, D. [71] | Lloyd et al. (2015) explore how the tourist activities managed by the ECB aim at social change through the sharing of indigenous knowledge, ways of being and practices with non-indigenous people during the tours, while ensuring that the company is sustainable |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elmo, G.C.; Arcese, G.; Valeri, M.; Poponi, S.; Pacchera, F. Sustainability in Tourism as an Innovation Driver: An Analysis of Family Business Reality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156149

Elmo GC, Arcese G, Valeri M, Poponi S, Pacchera F. Sustainability in Tourism as an Innovation Driver: An Analysis of Family Business Reality. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):6149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156149

Chicago/Turabian StyleElmo, Grazia Chiara, Gabriella Arcese, Marco Valeri, Stefano Poponi, and Francesco Pacchera. 2020. "Sustainability in Tourism as an Innovation Driver: An Analysis of Family Business Reality" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 6149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156149

APA StyleElmo, G. C., Arcese, G., Valeri, M., Poponi, S., & Pacchera, F. (2020). Sustainability in Tourism as an Innovation Driver: An Analysis of Family Business Reality. Sustainability, 12(15), 6149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156149