Correction: Ludvig, A.; et al. Governance of Social Innovation in Forestry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1065

- (1)

- Replacing the email of the fifth author Wilding Mariawith

- (2)

- Deleting two sentences in the second paragraph of Section 4. “Results” on page 6.The deleted part reads as follows:In the Spanish case, a group of forest owners started to organize themselves into groups to better fight forest fires as there was no effective public infrastructure available to address this need. This activity is particularly novel as it introduced a type of bargaining system, namely that individuals would engage in the often dangerous activity of fighting a fire on somebody else’s property based on the trust that if the same event occurs their own land, others would reciprocate.

- (3)

- Deleting two sentences in Section 4.3 “Austria’s “Nature Park Specialities” Association” on page 7.The deleted part reads as follows:

- In the Spanish case, spontaneous self-organisation took place because of a pressing need and this led to further formalisation and institutionalisation.

- In the Spanish case, it is the backbone of the entire endeavour as all firefighters are volunteers and funds are used purely for purchasing equipment such as protective clothing, specialized vehicles and the maintenance of these two things.

- (4)

- Deleting the Section 4.4 “Forest Fire Volunteer Groups in Spain” in page 8.The deleted part reads as follows:Fighting forest fires is carried out by local forest owners in parts of Catalonia in Spain [47] who organised during the 1990s and formed an association as forest fire defence groups. The need for this was that there was no effective public infrastructure to defend from forest fires. The arrangement is based on trust: Each forest owner helps in combating the wildfire for other forest owners whilst knowing that these will do the same for his/her land. Such cooperation functions best under the condition that the forest owners know each other in person have regular contact and good relationships in the area. Yet, the activity is highly dangerous, and this requires extra personal will and investments. With the time, the group they managed to reach recognition by local policymakers and new legislation was introduced for their legalisation and public support, the Catalan law regulating the “regulació d’Agrupacions de Defensa Forestal” [50]. This regulation provides the wild fire volunteers with equipment such as garments or cars for the activity. Their example led to positive changes in the Catalonian regional regulation in support of this type of organisation.

- (5)

- Deleting one sentence in Section 5 “Discussion: Governance of Social Innovation in Forestry” on the paragraph of (iii) Distinct policy features on page 10 i.The deleted part reads as follows:In the Spanish case, it was clearly the new regional regulation that provided an institutional framework whilst simultaneously leading to recognition and some funding possibilities for the Forest Fire Volunteer groups.

- (6)

- Replacing word “four” with the word “three” throughout paper related to three examples (case studies).In the abstract, word “four” was replaced by word “three” in the following two sentences:

- To answer this question, we first identified three very different cases across Europe that are compatible with the criteria of social innovation.

- In the cases considered, it is evident that the sheer determination and voluntary investment of time and effort by key individuals, who were convinced of the value of the idea for the community, provided indispensable impetus to all three social innovations.

On page 2, word “four” was replaced by word “three” in the following two sentences:- The foregoing led us to the decision to study three cases of social innovation in three very different rural areas across Europe.

- The subsequent results section will draw its findings from a comparison of the three cases by analysing their differences and commonalities before finally discussing their nature from the perspective of their deductively derived criteria for social innovation: community activities, triggers, internal organisation, financing and support.

On page 4, word “four” was replaced by word “three” in the following three sentences:- From this pool of eleven cases, we identified the three best suited to our research question and that show the diversity of social innovation across forest activities and across European regions.

- All three cases formed cooperative associations with strong involvement from civil society and produced collective benefits within the forest sector, thus featuring prominently governance aspects.

- Furthermore, these three cases feature geographically distinct regions in Europe and also different products and activities, illustrating variety of institutional and natural conditions for developing social innovations.

On page 6, word “four” was replaced by word “three” in the following sentence:- Moreover, all three cases characterise involvement of several actors and institutions that are supported by associations. Finally, one of them actively involves socially vulnerable groups in their training and skills development programme (UK).

On page 10, word “four” was replaced by word “three” in the following three sentences:- In all three cases, being able to secure volunteers to work is one of the most important features.

- Volunteer work was especially important during the founding phase in all three cases, and it still has an indispensable role in the UK case.

- In particular, we have observed in the three considered cases from the forest sector (i) strong agency, (ii) creative and novel related impacts on their social innovation endeavours [8,9,19,23,25].

- (7)

- To clearly indicate that the research included three instead of four cases, the authors wish to remove some sentences:Replacing the original version in page 4 in Section 3.1:Our cases include a “Charcoal Land Initiative” in Litija, Slovenia (SI), a community forestry enterprise in Wales (UK), the “Nature Park Specialities” association in the Austrian region of Styria (AT) and “volunteer wildfire groups” in Catalonia (ES).withOur cases include a “Charcoal Land Initiative” in Litija, Slovenia (SI), a community forestry enterprise in Wales (UK) and the “Nature Park Specialities” association in the Austrian region of Styria (AT).Replacing the original version in page 4 in Section 3.2:1) between July and December 2014—in the frame of the STARTREE project, this refers to the Welsh and the Austrian case, and 2) between July and December 2018—in the frame of the SIMRA project for the Spanish and the Slovenian case.with1) between July and December 2014—in the frame of the STARTREE project, this refers to the Welsh and the Austrian case, and 2) between July and December 2018—in the frame of the SIMRA project for the Slovenian case.Replacing the original version on page 5 in Section 3.2:In the Spanish case, apart from semi-structured interviews related to innovation process itself, great understanding of the case conditions was provided in the already published material from SIMRA project (including authors of this paper) [33,34,39–41].withApart from semi-structured interviews related to innovation process itself, great understanding of the case conditions was provided in the already published material from SIMRA project (including authors of this paper) [33,34,39–41].Replacing the original version on page 6 in Section 4:In result, our selection conforms to the scholarly standards for innovativeness [10] because the cases either introduce a new idea for a historical, traditional product (Slovenia) or commercialise a good or service in a new way that is unique for the sector and the region (UK, Austria and Spain) [45] (p. 11) [46] (p. 5).withIn result, our selection conforms to the scholarly standards for innovativeness [10] because the cases either introduce a new idea for a historical, traditional product (Slovenia) or commercialise a good or service in a new way that is unique for the sector and the region (UK, Austria) [45] (p. 11) [46] (p. 5).Replacing the original version on page 8 in Section 4.3 (after Table 1):It is important to note that all activities take place in localised areas where economic conditions are poor and local communities are suffering the aftermath of deteriorating or collapsed industrial production (AT, SI), are engaged in farming and forest management under increasingly difficult climatic conditions (ES), as well as often facing high rates of land abandonment, unemployment (ES, SI, UK), and/or an ageing local population (AT).withIt is important to note that all activities take place in localised areas where economic conditions are poor and local communities are suffering the aftermath of deteriorating or collapsed industrial production (AT, SI), are engaged in farming and forest management under increasingly difficult climatic conditions (AT), as well as often facing high rates of land abandonment, unemployment (SI, UK), and/or an ageing local population (AT).Replacing the original version on page 8 in Section 4.3 (after Table 1):The cases we examined were sustainable or even flourished because of the continuous eorts of a range of various associations (UK), consulting firms (AT) and public administrations (SI, ES) (Table 1, above).withThe cases we examined were sustainable or even flourished because of the continuous efforts of a range of various associations (UK), consulting firms (AT) and public administrations (SI) (Table 1, above).Replacing the original version on page 10 in Section 4.3:The initial ideas originated from specific individuals (innovators) who had the will to turn their ideas into reality. Some were subsequently supported either by a consulting agency (such as the ÖAR in Austria), by regular funding (TECT funding in the UK case), by a regulative policy instrument that provided a legal base for the activities and the opportunities to receive further developmental funding (the Spanish case).withThe initial ideas originated from specific individuals (innovators) who had the will to turn their ideas into reality. Some were subsequently supported either by a consulting agency (such as the ÖAR in Austria) or by regular funding (TECT funding in the UK case).Replacing the original version on page 11 in Section 5 (i) Cooperation and collective action:The relationships that develop are, at least initially, largely based on trust and in the Spanish case, trust has proven to be enduring and decisive factor that provides ongoing impetus to the dangerous activity of fighting forest fires.withThe relationships that develop are, at least initially, largely based on trust.

- (8)

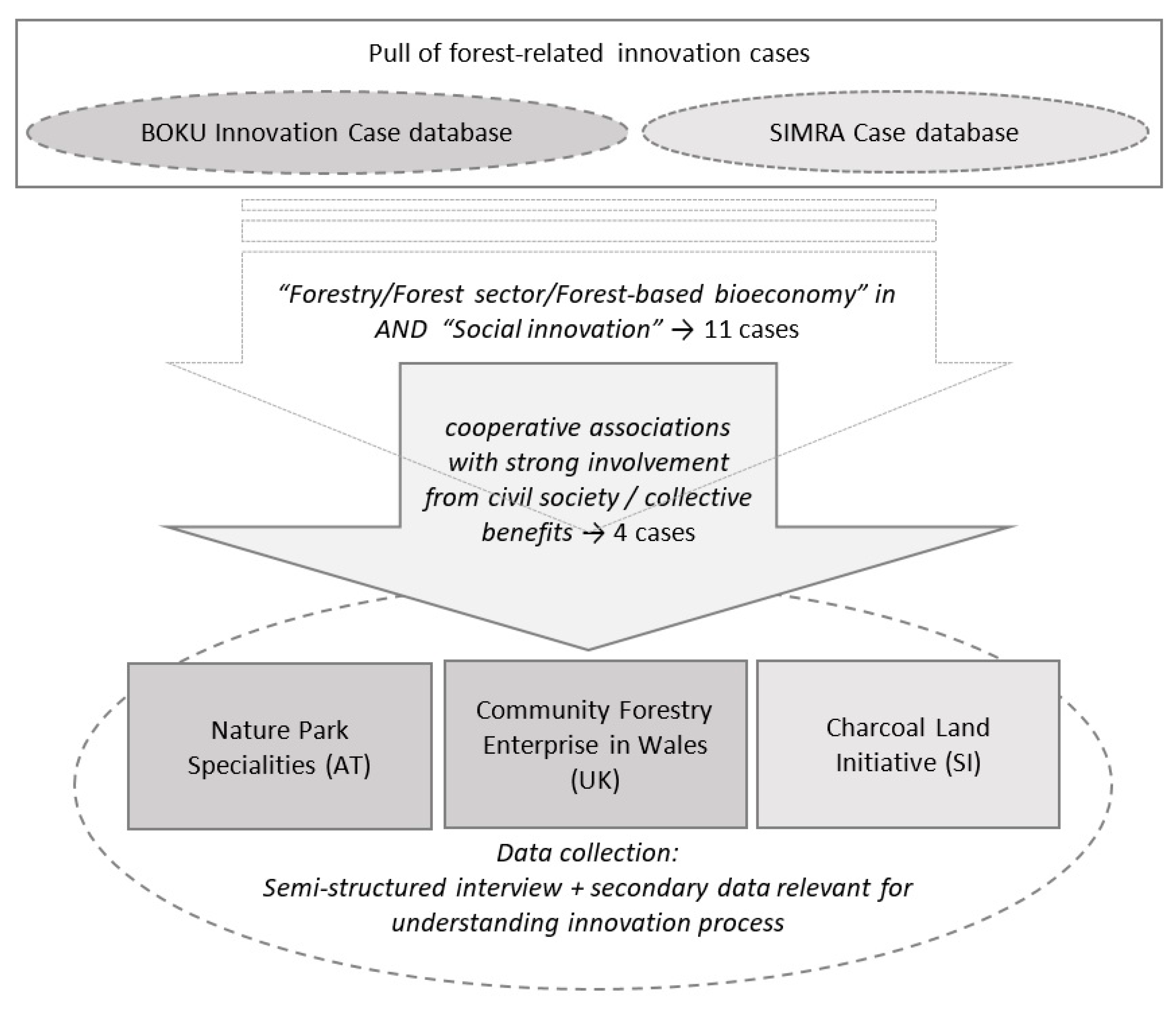

- Replacing Figure 1:withFigure 1. Data collection process for identifying social innovation in relation to forestry.Figure 1. Data collection process for identifying social innovation in relation to forestry.

- (9)

- Replacing Table 1:Table 1. Results: Types, triggers, governance features and main impact at institutional policy level of four social innovations in the forest sector (elaborated by the authors).withTable 1. Results: Types, triggers, governance features and main impact at institutional policy level of four social innovations in the forest sector (elaborated by the authors).

Name Social Innovation Features Type of Activity in Forest Sector Key Initial Triggers Main (Financial) Support New Governance Structures and New Actors Roles Main Impact at Institutional/Policy Level The Charcoal Land Initiative (SI) Volunteer collective engagement, historical innovation Non-wood forest product - Regional economic deprivation

- An initiative of two local actors

- Revival of interest in charcoal burning

- Volunteer work

- Income from selling charcoal

- Formation of new network/initiative

- Formation of Association on national level

- Broadened forest policy perspective (via creation of new interests/revived products)

- Activation of private forest owners in this activity

Coppicewood College in Wales (UK) Volunteer collective engagement, regional innovation Non-wood forest product and ecosystem services - New land reform opened up opportunities

- An initiative by a group of locals

- Volunteer work

- Income from courses

- Grant funding (TECT)

- Community forest enterprise become main actor (bottom-up)

- Community engagement in forest management

Austrian Nature Park Specialties (AT) Volunteer collective engagement, market innovation Non-wood forest product and ecosystem services - Foundation of nature parks beforehand

- The need to market the products from the nature parks

- Member fees by participating nature parks

- Some small project funding (LEADER)

- Involvement of consultancy agency

- Active bottom-up role of local producers enhanced

- Establishment of a label and novel marketing concept

Forest Fire Volunteer

Groups in Spain (ES)Volunteer collective engagement, regional innovation Hazard and risk prevention - An immediate and on-going threat

- Public system was ineffective (poor infrastructure)

- Volunteer work

- Some support for equipment through new regional legislation

- Formation of voluntary fire fighters groups

- Changes in national laws (Catalonian regional regulation in support of this type of organisation)

Table 1. Results: Types, triggers, governance features and main impact at institutional policy level of three social innovations in the forest sector (elaborated by the authors).Table 1. Results: Types, triggers, governance features and main impact at institutional policy level of three social innovations in the forest sector (elaborated by the authors).Name Social Innovation Features Type of Activity in Forest Sector Key Initial Triggers Main (Financial) Support New Governance Structures and New Actors Roles Main Impact at Institutional/Policy Level The Charcoal Land Initiative (SI) Volunteer collective engagement, historical innovation Non-wood forest product - Regional economic deprivation

- An initiative of two local actors

- Revival of interest in charcoal burning

- Volunteer work

- Income from selling charcoal

- Formation of new network/initiative

- Formation of Association on national level

- Broadened forest policy perspective (via creation of new interests/revived products)

- Activation of private forest owners in this activity

Coppicewood College in Wales (UK) Volunteer collective engagement, regional innovation Non-wood forest product and ecosystem services - New land reform opened up opportunities

- An initiative by a group of locals

- Volunteer work

- Income from courses

- Grant funding (TECT)

- Community forest enterprise become main actor (bottom-up)

- Community engagement in forest management

Austrian Nature Park Specialties (AT) Volunteer collective engagement, market innovation Non-wood forest product and ecosystem services - Foundation of nature parks beforehand

- The need to market the products from the nature parks

- Member fees by participating nature parks

- Some small project funding (LEADER)

- Involvement of consultancy agency

- Active bottom-up role of local producers enhanced

- Establishment of a label and novel marketing concept

Reference

- Ludvig, A.; Rogelja, T.; Asamer-Handler, M.; Weiss, G.; Wilding, M.; Zivojinovic, I. Governance of Social Innovation in Forestry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ludvig, A.; Rogelja, T.; Asamer-Handler, M.; Weiss, G.; Wilding, M.; Zivojinovic, I. Correction: Ludvig, A.; et al. Governance of Social Innovation in Forestry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1065. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145767

Ludvig A, Rogelja T, Asamer-Handler M, Weiss G, Wilding M, Zivojinovic I. Correction: Ludvig, A.; et al. Governance of Social Innovation in Forestry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1065. Sustainability. 2020; 12(14):5767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145767

Chicago/Turabian StyleLudvig, Alice, Todora Rogelja, Marelli Asamer-Handler, Gerhard Weiss, Maria Wilding, and Ivana Zivojinovic. 2020. "Correction: Ludvig, A.; et al. Governance of Social Innovation in Forestry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1065" Sustainability 12, no. 14: 5767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145767

APA StyleLudvig, A., Rogelja, T., Asamer-Handler, M., Weiss, G., Wilding, M., & Zivojinovic, I. (2020). Correction: Ludvig, A.; et al. Governance of Social Innovation in Forestry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1065. Sustainability, 12(14), 5767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145767