Abstract

As a small island in the Mediterranean Sea, Cyprus must develop a sustainable tourism model. Although the ongoing political problems in Cyprus provide additional challenges, the number and activities of women ecotourism entrepreneurs demonstrated an inspiring growth over the last decade in the northern part of Cyprus. The well-being and flourishing of these women entrepreneurs influence their participation and further involvement in the sector. Psychological empowerment plays a significant role in achieving a flourishing society, and our results reveal that ecotourism can be used to create positive change in women’s lives. We study how the mindsets and flourishing levels of these ecotourism entrepreneurs are related and how empowerment can change the direction of this relationship. Our research model was developed based on the self-Determination theory. Surveys were distributed to 200 women ecotourism entrepreneurs in rural areas of Northern Cyprus. We demonstrate that women who have growth mindsets, i.e., those that believe people’s characteristics such as abilities are not fixed, experience lower levels of flourishing, perhaps contrary to what some might expect. This result may be due to the presence of gender inequality and may be an outcome of living in a region where a frozen conflict places additional external constraints on women entrepreneurs. However, as we predict, psychological empowerment changes the direction of this relationship. When psychological empowerment is high, women with a higher level of growth mindset experience a greater level of flourishing, even in an unfavorable context. This is the first study which analyzes women ecotourism entrepreneurs in Northern Cyprus. Moreover, this is the first study that focuses on the relationship between growth mindset, flourishing and psychological empowerment. The results can be used by governmental and non-governmental organizations as a source in their decision-making processes while managing and coordinating microfinance opportunities for rural development to support women’s empowerment and well-being.

Highlights

Growth mindset and the flourishing level of women ecotourism entrepreneurs have a significantly negative relationship in Northern Cyprus.

Psychological empowerment has an interaction effect that changes the direction of this relationship, toward a significantly positive relationship.

Ecotourism is a tool to empower women living in rural areas.

1. Introduction

As a Mediterranean island with ample sunshine and beautiful beaches, Cyprus has long been a tourism destination. Although the political problem that divides the north and south has resulted in two separate administrations, both sides had focused on mass tourism strategies for rapid economic results but have recently become increasingly concerned with the potential damage that mass tourism may have on the environment and the issue of sustainability. In the past, policy makers developed incentive systems to attract large-scale investments, but now there is more interest in encouraging smaller-scale and sustainable tourism offerings which involve the local population. Northern Cyprus has seen an increase in women ecotourism entrepreneurs, who have been encouraged by community development programs and festivals [1].

Tourism is one of the routes through which women can be integrated into economic and social life [2], and entrepreneurship may help women, particularly those who live in rural areas where the job opportunities are limited, to increase their self-reliance and empowerment. Especially for the women who live in rural areas, the development of ecotourism can provide work opportunities. Taking part in ecotourism activities gives those women the freedom to earn their own money and be economically independent, which also enhances their social condition [3].

Although there has been increased interest in academic studies of ecotourism and entrepreneurship in general, we still lack an understanding of the factors that lead to well-being among ecotourism entrepreneurs [4]. In particular, the factors influencing the success of women ecotourism entrepreneurs whose empowerment and involvement can have significant social impact have not received adequate attention in the existing literature. To provide a better understanding of the impact of ecotourism on the lives of the women ecotourism entrepreneurs who typically did not have prior professional experience, we investigated how their mindsets, based on how empowered they feel, influence their well-being and feelings of flourishing.

Studies on mindset have generally argued that those with a growth mindset will perceive social and personal attributes as changeable, will have more positive emotional experiences and thus will have higher levels of thriving, flourishing and fulfillment [5,6]. However, more recent research has revealed that the positive results of growth mindset require certain contexts in which these positive outcomes could be possible [7]. In the current study, in the context of Northern Cyprus, where gender inequality and a frozen conflict place restrictions on women, we expect to see a negative relationship between growth mindset and the level of flourishing due to these restrictions. Based on the previous studies [8,9,10] we expect that women entrepreneurs who believe in themselves and want to take actions to control their lives will be more frustrated if they are held back as a result of these external factors and their flourishing level is lessened.

Contribution of the Study

The current study examines the mindset and flourishing relationship among ecotourism entrepreneurs in Northern Cyprus and explores how psychological empowerment through sustainable tourism can enable them to reach higher levels of thriving and flourishing. The study provides findings from a context that may be considered less supportive for growth mindset women entrepreneurs. Furthermore, by investigating how the impact of empowerment may influence the mindset–flourishing relationship, the study contributes to the theoretical discussions in the mindset literature.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Well-Being and Flourishing

Flourishing means having a good life. It is a feeling of well-being, both physical and mental. It means the highest level of psychological well-being [11,12,13]. The concept of well-being can be defined as a multi-dimensional construct that considers hedonic (experience of pleasure) and eudemonic (the experience of meaning or accomplishment) ideas of prosperity [14]. However, the eudemonic and hedonic dimensions work simultaneously. A life rich in both hedonic and eudemonic aspects leads to the maximum level of well-being or flourishing. Therefore, combined feelings of accomplishment, which are higher-order (eudemonic) experiences, and feelings of pleasure, which are lower-order (hedonic) experiences, differentiate the concept of higher levels of well-being from the concept of the mere absence of suffering. When we experience personal achievement, meaningful creative contribution, altruistic experiences, these will not only count as eudemonic experiences but also provide hedonic pleasure.

Evaluating the flourishing levels of individuals is important because findings prove that flourishing is essential for societies and organizations [15]. Just as accounting is used to understand the financial health of organizations and countries, we are seeing more interest in taking measurements of well-being to understand their emotional health. Policy makers are becoming more interested in developing policies that will enhance the well-being of societies in a more balanced way. The World Health Organization (WHO), the European Public Health Association (EUPHA) and the European Commission (EC) have emphasized the importance of linking planning and health instead of treating them as separate domains [16].

Studies show that flourishing also brings benefits to the community in terms of improved public health [15,17].

VanderWeele and VanderWeele et al. indicate that flourishing is not limited to improved psychological well-being but also includes every facet of an individual’s life [18,19]. Therefore, different areas of flourishing have been studied. Feeling happy and fulfilled, psychological and physical health, desires and ambitions, personality and honor, and social interactions can be listed as the different areas of flourishing. Furthermore, economic stability is also an important element in preserving flourishing.

Deci and Ryan (1985) suggest that in order to experience well-being, the basic psychological needs of competence, relatedness and autonomy must be met, as specified by the self-determination theory [8].

2.1.2. Implicit Person Theories

Carol Dweck, a well-known writer in the field of motivation, popularized the concept of “mindset” to demonstrate that the general beliefs that we have about whether people’s characteristics are stable or malleable—our lay theories—will influence our attitudes and behaviors [20]. Dweck (1986) proposed that mindsets can be classified as fixed and growth [21]. People who have fixed mindsets believe that people’s personal traits, such as knowledge, inventiveness and ability, are foreordained and stable characteristics [22]. Individuals with fixed mindsets accept that if a person is insufficient in some way, their situation will remain unchanged. On the other hand, people who have growth mindset trust that people’s fundamental capacities can continue to improve through hard work and commitment. They believe that these natural traits are the initial stages for achieving accomplishments through learning, hard work and endurance. These assumptions or beliefs are also referred to as the implicit person theory (IPT), a particular presumption about the adaptability of a person’s qualities that affect his or her conduct [21,22,23].

Dweck and her colleagues have focused on implicit person theories [24,25]. A person who possesses a fixed “implicit person theory”—also called entity theorist—will have a fixed outlook about people and trust that people’s capacities are based on their fundamental abilities and are stable [20]. This leads them to think that these capacities are the reason for their level of success or failure. Such individuals are more likely to believe that their outcomes are due to their unchanging dispositional capacities and ignore situational factors [26].

2.1.3. Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory (SDT) is a comprehensive theory of motivation that encompasses several sub-theories. A distinction is made between autonomous motivation—feeling tempted to do something because we find it interesting or perceive it as our own wish—versus controlled motivation—feeling that something must be done because of some pressure or to satisfy someone else. However, SDT does not treat controlled and autonomous motivation as dichotomous, but accepts that they represent the theoretical maximum points of a continuum. As the level of autonomy increases, the type of motivation changes from controlled to autonomous.

SDT encompasses the Basic Psychological Needs Theory, which states that autonomy competence, relatedness and psychological needs must be met [8]. Thus, women ecotourism entrepreneurs need autonomy and freedom to decide and act independently, the competence to perform effectively and deal with financial, operational and managerial issues, and relatedness to find support from their contacts.

The cognitive evaluation theory, as a sub-theory of SDT, argues that the context may be supportive or controlling. A controlling context would use external conditional rewards or penalties, which for individuals already performing the task and getting intrinsic rewards from the task itself would mean a loss of autonomy. For example, in a non-profit organization where people were presumably engaged in their tasks due to the alignment of their personal values and goals with the organization, a loss of autonomy and intrinsic motivation was experienced after the introduction of merit pay systems [9]. For entrepreneurs that went into business with a desire to use their creativity and innovation, an environment with too many external conditions can lead to frustration. Women ecotourism entrepreneurs will experience this when they are operating under pressure from society to conform to certain norms that restrict their autonomy, competence and relatedness.

The causality orientation theory is also a sub-theory of SDT and focuses on the individual differences of general orientation in different people. Those with an autonomy orientation have a higher need for autonomy and those with a control orientation will be more comfortable with externally imposed deadlines and clear rules.

According to the self-determination theory, individuals from all societies have an essential psychological need for autonomy, capability and relatedness. It is argued that if these requirements are bolstered by social settings, flourishing is enhanced [8,9,10]. When the social context supports autonomy, and the individual has an autonomy orientation, this will increase motivation [9]. Furthermore, at a social level, Putnam [27,28] and Helliwel et al. [29] argue that the well-being of societies is also dependent on the social capital of individuals. Conversely, if the environment is controlling and the individual has an autonomy orientation, this may result in a loss of motivation. If the cultural context and other external environmental factors put restrictions and limitations on those necessities, the level of flourishing will decrease.

2.1.4. Women’s Entrepreneurship and Ecotourism in Northern Cyprus

The inflexible roles and responsibilities of women that are imposed by society and cultural norms inherited from past generations should not be overlooked when discussing the position of women in work life. Women and men are exposed to certain gender restrictions from their birth to their death.

A UN Report on women shows that 70% of the global population who suffer from low living conditions are women. Although women work more than men, only 10% of world income goes to women, and they own less than 1% of the world’s total assets [30]. Moreover, the number of uneducated women around the world is much higher than the number of uneducated men due to the inequalities that women face in society [28]. This is what encourages researchers to investigate ways to improve women’s lives by searching for ways in which they can become involved in the workforce and take part in the world economy. As is widely known, if women change, the whole environment around them changes.

Women entrepreneurs, who are the focus of our research, contribute to the general economy of their country through their newly established businesses. Their willingness to achieve long-term success in the tourism industry affects the economy in a positive way. Worldwide, an increased number of women have started to participate in entrepreneurial exercises for money-related reasons as well as for psychological and social empowerment reasons. Most of these women entrepreneurs, however, also expect to have a balanced family life while engaging in their business activities [31,32].

According to prior research, women are more likely to be engaged in entrepreneurship that is directed at social and environmental problems [33]. Evidence confirms that necessity-based motivation factors are more common among female business entrepreneurs than among male business entrepreneurs. Various studies conducted in the USA, for instance, have demonstrated that female business entrepreneurs tend to be less affected than their male counterparts by the motivation to be more powerful, richer and to be their own boss. Rather, women tend to be inspired by earning an income in order to improve their standard of living [34].

In developing countries, studies have revealed that, for women, necessity motivation has a greater effect compared to opportunity motivation [35]. In developing countries, there is an increasing rise in the number of female entrepreneurs who conduct economic activities. The researchers mention that these women contribute to the general economy with their generous commitments. Heyzer [36] pointed out that those women who take part in the economy as small business owners have a significant effect on strengthening and improving women’s living standards.

One of the routes through which women can be integrated into economic and social life is tourism [2]. With the development of tourism, numerous work opportunities for women have led them to employment and entrepreneurship. In addition, tourism gives them the freedom to earn their own money and be economically independent, which also enhances their social condition. Tourism is an important, employment-stimulating sector which is thriving around the world. It is estimated by the World Tourism Organization that approximately 96.7 million individuals are employed in the tourism sector; if indirect occupations are added to this amount, the sum is approximately 254 million employees [37,38]. This energetic industry is the principal source of national income, job creation and private sector growth in numerous nations.

In recent years, ecotourism has emerged as a means of long-term, sustainable community development [39]. Done properly, community-based ecotourism (CBET) should add to the natural preservation of wildlife and the environment and provide job opportunities for the community to obtain income [40]. To accomplish sustainable development in tourism, women should be encouraged to take part in tourism activities [3]. Excluding some special studies [38], gender has not been the main focus of research in ecotourism. However, there are many aspects of the gender perspective in ecotourism, as it is an important vehicle for women’s entrepreneurship, especially in rural areas.

Knowing the importance of supporting women’s entrepreneurship for its economic, social and psychological benefits, in our research, we chose women entrepreneurs who were involved in ecotourism activities in Northern Cyprus as our study population.

2.1.5. Cyprus as a Frozen Conflict Area

Cyprus is categorized and accepted as being a frozen conflict state, as there has been an ongoing political conflict between the recognized Republic of Cyprus and the unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The negotiations have continued for more than 40 years. In the meantime, Turkish Cypriots continue to live in an unrecognized country, faced with the consequences of a frozen conflict. Although the political problems thwart the possibility of a solution, people try to build a life where they satisfy their needs and try to achieve their goals. Like anywhere else, some choose to become entrepreneurs. In particular, women who live in rural areas, where job opportunities are limited, want to feel independent and empowered through entrepreneurship.

95% of the private sector in Northern Cyprus, consist of small- to medium-size businesses [41]. Furthermore, 80% of these businesses are sole proprietorship or family businesses [42]. According to a study, the appeal of working in the government sector and the limited availability of information, coupled with political and economic barriers, diminish the push factors for entrepreneurship as a career alternative [42]. However, the amount of women entrepreneurs in Northern Cyprus can be considered high according to the EU standards [43]. Although the push factors are not strong, people—mainly women who cannot find a governmental job—are pulled into entrepreneurship. They do so to be more social and to earn their own money, in order to become self-sufficient [43].

At that point, ecotourism plays an important role in empowering those women entrepreneurs, as Cyprus offers historical and natural beauty to tourists. However, tourism activities are limited and very difficult due to the state of frozen conflict. Economic and political embargoes, such as the lack of direct flights and being excluded from international organizations, cause problems and limit the opportunities. These limitations and uncertainty put psychological constraints on entrepreneurs. Those who have a growth mindset believe in change and believe they can achieve their goals, but also know and see the reality of the country they live in. This awareness leads them to feel less flourished and constrained.

In addition to the above-mentioned economic and political constraints, as Purrini [44] mentioned, women who live in these conflict zones, particularly in the rural regions, should be empowered, as they cannot take part of the decision making process. Women entrepreneurs should be supported and encouraged with training and financial support because the lack of capitalis a further major obstacle they face [45].

Due to the frozen conflict and its political consequences, Northern Cyprus has been mainly supported and influenced by Turkey since 1974. Therefore, Turkish culture and traditions have spread to the area. In the Gender Gap Report (2020) published by the World Economic Forum, Turkey is ranked 130 out of 153 countries, as shown in Table 1 [46]. This shows a clear gender inequality in the country and hence in Northern Cyprus as well. In 2016 and 2017, a study was conducted in Cyprus by the “Security Dialog Initiative”, which is a non-governmental organization, together with the Gender Score Cyprus Project, implementing the Social Cohesion and Reconciliation (SCORE) index to determine the state of gender inequality in Northern Cyprus. The findings confirmed that Turkish Cypriot society is affected by a traditional culture where toxic masculinity is endorsed. According to this study, husbands’ disciplinary actions toward their wives are backed by society. Also, society reduces the role of women to parenthood. The study shows that Turkish Cypriot women cannot freely express themselves in society; they feel that they are disadvantaged with regard to sharing family wealth, and they present lower levels of economic and political independence [47].

Table 1.

Gender Gap in Turkey according to the Global Gap Index Report 2020.

Powerful traditional gender roles lead society to expect women to be responsible for household duties and childcare. As a result of this work overload, women have very limited or no time to invest in themselves to improve their skills, have a hobby or join society and become involved in political activities. In addition to these findings, the most dramatic outcome of the study is that there is neither an awareness of gender inequality nor an understanding of the concept of gender equality. Both men and women accept gender inequality situations as norms and do not attempt to make any changes [47].

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. Mindset and Flourishing

Previous studies have demonstrated the links between personality traits, well-being and flourishing [48]. Helliwell [49] found a direct connection between identity and well-being. Individuals with higher self-respect appear to be less inclined to experience despair. Hmieleski and Sheppard [50] argued that women entrepreneurs who are creative experience higher degrees of well-being and start-up business success. However, the self-determination theory says that individuals from all societies have an essential psychological need for autonomy, capability and relatedness. If these needs are bolstered by social settings, flourishing is enhanced. On the other hand, if the cultural context and other external environmental factors put restrictions and blockages on these needs, the level of flourishing declines [8,9,10].

Our research was conducted in Northern Cyprus, where gender inequality and frozen conflict play an important role, since these factors place restrictions on women. Therefore, we anticipate a negative relationship between growth mindset and the level of flourishing as a result of these restrictions. When women entrepreneurs believe in themselves and want to take actions for their lives, but are restricted as a result of these external factors, their flourishing level will be lessened compared to that of women who may already be convinced that change is not possible and accept their fate.

Therefore, based on the self-determination theory, we expect to see a negative impact of growth mindset on flourishing. We expect that people with growth mindset will think they can change things and achieve the things they want. However, in the context of Northern Cyprus, where they cannot make a change and achieve their goals due to the contextual limitations they face, they will be more frustrated and will experience less flourishing. Therefore, we developed our first hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Growth mindset has a negative relationship with flourishing.

2.2.2. Psychological Empowerment, Growth Mindset and Flourishing

Elias and Ferguson [51]. define empowerment as the right of people to make individual choices, make their decisions on their own and have dignity. Researchers argue that the process of empowerment aims to enable individuals to obtain more power to become more self-reliant and self-confident people, to create their own way of living and, therefore, to become part of the process of social change [52].

According to Spreitzer [53] (p. 1443), “psychological empowerment refers to the intrinsic task motivation that results in feelings of competence, impact, task meaningfulness and self-determination related to the work-role”. Empowering circumstances which provide the prospects for being independent pose a challenge, enhance accountability and make people appreciate what they have. In exchange, such appreciation leads to a sense of significance, proficiency, self-determination and power [54].

In the tourism context, when the inhabitants experience psychological empowerment they feel “pride” and “self-esteem”, as they feel unique and think they have significant abilities and products to give to tourists [55]. Studies indicate that when citizens are not only involved but also empowered, their impact becomes much greater and leads to more sustainable efforts [56,57,58]. makes the distinction between mere involvement and empowerment and argues that empowerment is the “top end of the participation ladder where members of a community are active agents of change and they have the ability to find solutions to their problems, make decisions, implement actions and evaluate their solutions”[56] (p. 631). Community-based ecotourism where citizens are actively empowered socially, politically and psychologically is a key element of sustainable tourism [58].

Under normal circumstances, the relationship between the growth mindset and flourishing is expected to be positive [49]. However, people with a growth mindset who are restricted and thus disappointed by the conditions of the country they live in, when they repeatedly experience that in spite of their enthusiasm and efforts they cannot introduce the change that they believe could have been possible, and feel unappreciated, will not see themselves as valuable and useful [8]. Among the individuals with a higher level of growth mindset who believe that people and situations are not fixed but changeable, the constraints will lead to a feeling of unfulfilled potential.

However, we believe that women with higher levels of growth mindset will indeed experience greater flourishing if they are psychologically empowered through tourism. If there are community-based tourism activities in the regions where they live and if they are involved in, and empowered by, these sustainable tourism activities, they will feel useful and experience meaning in what they do [56]. Often, community-based tourism is supported by training and development and educational activities that contribute to empowerment. When women feel proud of themselves as they receive positive feedback from the tourists who appreciate their products, services and environment, they feel more competent, empowered to make decisions, useful and effective in their family and their community [58]. Women with a growth mindset who do not perceive or experience psychological empowerment know that they are capable of doing the things they want but, as a result of environmental pressures and obstacles, cannot. They cannot offer the services and products they want to offer freely to tourists when they are blocked by the people around them, such as their husband, father or neighbors, or restricted by the dominant norms of their community. Women with a growth mindset will feel even worse if they are accused of neglecting the household chores that they are expected to perform and have to ask permission to their husbands [8].

Based on the self-determination theory, we expect that maintaining women’s empowerment will enhance their level of self-determination and lead to an increase in their subjective well-being. We believe that this relationship will be particularly stronger among the women entrepreneurs who have higher levels of growth mindset. Therefore, we expect to find a moderation effect of psychological empowerment that reverses the negative relationship between growth mindset and flourishing. As a result of this expectation, we developed our second hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Psychological empowerment interacts with the relationship between growth mindset and flourishing.

3. Method

3.1. Model of the Study

This research applied a cross-sectional survey and regression analysis to assess how psychological empowerment through tourism interacts with the relationship between growth mindset and the level of flourishing of women entrepreneurs living in rural regions of Northern Cyprus.

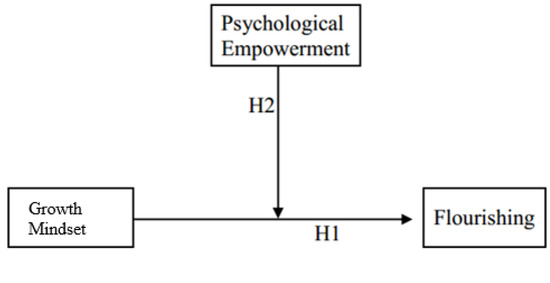

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model and the hypotheses of this study. This model tests the effect of growth mindset on the flourishing of women entrepreneurs who live in rural parts of Northern Cyprus and engage in ecotourism activities (Hypothesis 1). The study also tested whether psychological empowerment through tourism interacts with the relationship between self-growth mindset and flourishing (Hypothesis 2).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model.

3.2. Measures

To measure flourishing, the Turkish version of the Flourishing Scale, which has been adapted by Telef [59], was used in our study. To assess the psychological empowerment and growth mindsets of women entrepreneurs, the original scales were translated into Turkish and then translated back into English by two professional translators. They were compared with the original scales in order to check that the meanings of the items had been correctly translated into Turkish and would not be misinterpreted by the respondents. This process was performed according to the suggestions of Perrewé et al. [60]. Before distributing the questionnaires, a pilot study was completed to test that the questionnaires worked correctly. While preparing and distributing the questionnaires, the suggestions of Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff [61] were applied to protect our study from common method bias.

3.2.1. Growth Mindset

Growth mindset was assessed with the 8-item implicit person theory created by Levy and Dweck [62]. This scale has 4 items associated with fixed mindset, like “As much as I hate to admit it, you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. People can’t really change their deepest attributes”, and 4 items associated with growth mindset, like “People can always substantially change the kind of person they are”. Respondents were asked to rate the items using a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) and 6 (strongly agree). The previous research demonstrated the alpha coefficient of this scale to be 0.94, which shows the strong internal consistency of the scale [62]. We found the alpha coefficient of this scale to be 0.89 in our study.

3.2.2. Flourishing Scale

This scale consists of 8 items that evaluate respondents’ perceived success in major segments of their lives, for example their self-esteem, how competent they feel or if they think they have a purpose in life. Initially, this scale was named the “Psychological Well-being Scale”, but it was later changed to the “Flourishing Scale” to represent the content of the scale more accurately. The scale provides a single psychological well-being score [63]. The respondents were asked to rate answers on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 represents “strongly disagree” and 7 represents “strongly agree”. One item, for example, reads: “I lead a purposeful and meaningful life.” The scale’s reliability has been demonstrated [63]. The Turkish version of the scale also had reliable results, with an alpha coefficient of 0.80 [59]. When we applied this scale in our study, we found a, alpha coefficient of 0.83.

3.2.3. Psychological Empowerment

Resident Empowerment through Tourism Scale (RETS) was used to assess the psychological empowerment of women entrepreneurs engaging in ecotourism activities, as it is a reliable and valid measurement tool that assesses residents’ perceptions of empowerment [64]. The scale has 3 sections, to assess the psychological, political and social empowerment of residents through tourism. We have used the 5 items in the psychological empowerment subscale, consisting of statements such as “Tourism in … reminds me that I have a unique culture to share with visitors.” or “Tourism in … makes me proud to be a…resident.” The value of the alpha coefficient was 0.92 for this scale, which represents a strong construct reliability.

3.3. Questionnaire Administration

Following the suggestion of Hinkin [65], we applied a pilot study with 12 women entrepreneurs to test the items on a small scale before applying the survey on a larger scale. First, after the pilot study, to evaluate the substance and legitimacy of the scale items, some phrasings was corrected, as some of the words were found to be reasonably confusing, as suggested by DeVellis [66]. Essential modifications were made, and equivocal words were reworded.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was applied using Varimax Rotation in IBM SPSS Statistics program to find conceptually incompatible items with a correlation threshold of 0.40, as suggested by Kim and Mueller [67]. The analyses revealed 3 factors that cumulatively explain 62% of the deviation, with eigenvalues above 1. The consistency of the items in the instruments used in the study was checked with the threshold Cronbach’s alpha [68] of 0.70. One item from the flourishing scale had a loading below 0.50 and was eliminated, as recommended by Hair, Anderson, Tatham, Black and DeVellis [66,69].

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), as indicated by Hinkin [65], was used to assess the goodness of fit of the model and the items used in the model. The high loadings in the CFA demonstrate that the study has construct validity. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Composite Reliability (CR) were also used to ensure the internal consistency and illustrate the convergent and discriminant validity of the study.

3.4. Participants and Procedure

Context Population and Sampling

The purposive sample method was used. A list of sample populations was obtained from the Businesswomen Association of Northern Cyprus. The list consisted of 305 women entrepreneurs who were involved in ecotourism activities, such as traditional handcrafting and producing traditional food. The population also included boutique hotel or guesthouse owners and small restaurant owners who specialize in traditional foods. These women live in rural areas, mainly in small towns within five main regions of Northern Cyprus. Most of them were housewives before they became entrepreneurs. In each region, there is a mentor who helps these women in their operations. Generally, the mentors are the leaders of local women’s associations or, in some regions, mayors who are taking on the responsibility of leading ecotourism activities in their region and providing support to women entrepreneurs. We visited these towns to meet these women in person. The list we used was not particularly applicable, as most of the women were no longer engaged in these activities, and some of them were unreachable. Therefore, we found a woman entrepreneur from each town and through her, using the snowball technique, reached out to other women. We contacted 200 women and asked them to complete the questionnaire. Data were collected in the period between April and June 2018 by visiting the women and in their respective locations. Questionnaires were distributed to those women entrepreneurs, and we kindly requested that they complete these questionnaires after we explained to them our research purposes and how we maintained the confidentiality of our research. We asked them to complete the questionnaires, which consisted of four sections, including a demographic information section. Our aim was to gather information on self-growth mindsets, women’s psychological empowerment through tourism and women’s flourishing.

Figure 2 shows the locations where the data was collected, and Table 2 presents the demographic profiles of the respondents. The sample consisted of 200 women respondents from 15 villages located in rural parts of Northern Cyprus. Only 6 of them, representing 3% of the population, were younger than 25. This means that young women are less involved in the ecotourism sector in Northern Cyprus. Only 18 (9%) of them had undergraduate degrees, and 15 (7.5%) were postgraduate degree holders. This information shows that women with university education are less likely to be engaged in ecotourism entrepreneurship activities in rural areas.

Figure 2.

Number of Ecotourism Entrepreneurs Participating in the Study by Region.

Table 2.

Respondents’ profile (n = 200).

4. Results

We applied confirmatory factor analyses using the AMOS software to examine the goodness of fit of our study model. The findings are illustrated in Table 3. The fit indicators show figures that are accepted as good fit indications according to the thresholds shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Goodness of fit of the model.

All items show high loadings in their underlying variables. Table 3 shows that the Cronbach’s alpha figures are greater than the threshold of 0.70 [68] and that CRs are greater than the accepted level of 0.70 [70]. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) figures are also greater than the cut-off figure of 0.50 [69].

The figures obtained from the analyses, which are shown in Table 3 and Table 4, show proof of convergent and discriminant validity. The potential risk of common method bias was handled utilizing an analytical methodology. Harman’s single-factor test explained 32.25% of the variance; therefore, the possible danger of common method bias appears to have been reduced [61].

Table 4.

Means, SD and correlations of the study variables.

Table 4 shows the means, standard deviations and correlation estimates of the variables used in our study. As hypothesized, growth mindset and the level of flourishing of women entrepreneurs are negatively related (r = −0.223, p < 0.01). This result provides support for Hypothesis 1.

Table 5 shows that Hypothesis 2, which anticipated that psychological empowerment would moderate the relationship between growth mindset and flourishing, is supported, as we can see a significant level of interaction terms (β = 0.260, p < 0.01).

Table 5.

Flourishing as predicted by Growth Mindset and Psychological Empowerment.

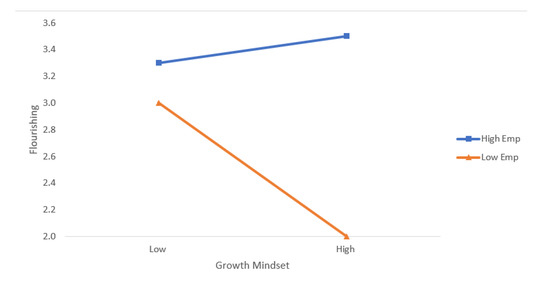

Therefore, complete support was reached. The research outcome approved the model of interest, as all hypothesized relationships were supported. Figure 3 shows the interaction effect of psychological empowerment in the relationship between growth mindset and flourishing.

Figure 3.

Slopes showing how Growth Mindset influences Flourishing differently under high and low Psychological Empowerment conditions.

As clearly seen in Figure 3, this study proves that when the psychological empowerment is low, women entrepreneurs’ level of flourishing declines when their growth mindset level increases. When we enter a low value of empowerment at 1 standard deviation below its mean, the estimated beta for mindset in predicting flourishing is negative (−0.27), whereas when we enter a high value of empowerment at 1 standard deviation above its mean value, the estimated beta for mindset in predicting flourishing is positive (0.15). This can be explained by the negative impact of gender inequality and the frozen conflict conditions in Cyprus. Women entrepreneurs are negatively affected when they believe that they can change and improve their skills, but also that they will not accomplish their dreams due to the limitations they face in their community. However, when we add psychological empowerment to this relationship, the negative result is reversed to a positive one, which shows that if we empower women entrepreneurs psychologically through tourism, they will feel strong and empowered, and this will change the relationship between growth mindset and flourishing. When the women are psychologically empowered, their growth mindset will lead to a more fulfilled, happier life, although there are many constraints that they still have to face.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In the relatively unfavorable entrepreneurial ecosystem and restrictive social context of Northern Cyprus, empowerment through ecotourism activities can enable especially women with a growth mindset to experience higher levels of well-being. Psychologically empowering growth-mindset women entrepreneurs improves their autonomy and self-belief, which leads them to flourish. This will not only benefit the women who become ecotourism entrepreneurs but also society and the economy overall. There will be a positive impact on the GDP through an increased female employment rate, and the knowledge, skills and capabilities that women gain will contribute to the overall well-being of society. Furthermore, a UNESCO (2019) [71] report shows that empowering women has significant benefits for the environment and argues that when women have a larger role in governance in society, the sensitivity to the social and environmental impacts of policies increases.

However, we note that the impact of empowerment through tourism is less felt by women who have a lower growth mindset or fixed mindset. Those with a fixed mindset are likely to believe that characteristics are generally stable and impossible to change; therefore, they may not be so concerned or motivated in the first place to introduce change in themselves and their communities. Thus, they may be less likely to utilize the opportunities introduced by empowerment, and their level of well-being does not change as much as that of women with a high growth mindset, who feel more confident to pursue their dreams and create change in their lives by taking action.

Many scholars and practitioners also believe that it is possible to increase the growth mindset through interventions [7]. Especially in the field of education, there are many applications and recommendations on how teachers can develop a growth mindset amongst their students. For example, the use of a metaphor such as “the brain is similar to a muscle that needs to be exercised through learning and grows stronger and smarter as a result.” This metaphor is reinforced by the teachers and replaces any belief that our talents, abilities and capacity is fixed and there is nothing we can do about it. Similarly, Dweck [20] argues that this can be extended to leadership and management, where managers can develop cultures where people believe in their own and other people’s ability to change and develop. These cultures would value trial and error as part of the process of development and not penalize individuals for taking the initiative to try something new, even if it does not always succeed.

The mindset literature has generally advocated the value of growth mindset. Our study reveals that growth mindset without empowerment will not lead to flourishing. Thus, we contribute to the mindset literature and theories by showing how empowerment is a critical factor that can enable those with growth mindset to achieve higher levels of flourishing.

5.1. Practical Implications of This Study

We believe that if women change, their surroundings will change as well. From this perspective, this study proves that the key to happiness for women is to become psychologically empowered, and shows that ecotourism can be used as a means to create positive change in women’s lives. Governmental and non-governmental organizations should support microfinance opportunities for rural development in such a way as to support women’s empowerment and well-being. Additionally, the study clearly illustrates that the authorities should provide training programs to support women who live in rural areas of Northern Cyprus, to teach them new skills and to empower them. As the study demonstrates, higher levels of empowerment will enable the increased flourishing and well-being of women entrepreneurs. International organizations such as the United Nations and the European Union, which are already active in Northern Cyprus to help the community to develop and to reach a political solution in Cyprus, should also further support ecotourism and enhance their activities to help local NGOs and potential women entrepreneurs, who can be included in ecotourism. Moreover, as suggested by Sdino and Magoni, shared housing associated with ecotourism can be introduced for these women in order to help them earn their own money and contribute to ecotourism [72].

The programs to empower women ecotourism entrepreneurs should not only offer support by delivering know-how or helping to eliminate barriers but also include interventions to increase growth mindset. However, some findings show that the results of such interventions may be temporary [7]. Therefore programs to develop growth mindset must be systematic. Conscious efforts for the empowerment of women entrepreneurs are also needed to develop supportive environments where peer norms encourage challenge seeking and adaptive attitudes.

The findings of this study can be used by governmental, non-governmental and international organizations to design new programs and organize capacity-building activities such as training programs, workshops and field trips at the grassroots level with current and potential women entrepreneurs.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

A qualitative study should be conducted to gain deeper insights related to our findings. Additionally, the scope of our study included only women entrepreneurs in Northern Cyprus, and future studies may replicate this study in other geographical regions to see how cultural and other contextual factors affect the relationship between growth mindset, psychological empowerment and the flourishing of women entrepreneurs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E. and C.T.; methodology, M.E. and C.T.; investigation, M.E.; formal analysis, C.T. and M.E.; writing and original draft preparation, M.E. and C.T.; writing, review and editing, C.T. and M.E.; visualization, M.E. and C.T.; supervision, C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gunsoy, E.; Hannam, K. Festivals, community development and sustainable tourism in the Karpaz region of Northern Cyprus. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2013, 5, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shokouhi, A.K.; Khoshfar, G.; Karimi, L. The Role of Tourism in Rural Women’s Empowerment, Case Study: Village Ziarat City of Gorgan, Planning and Development of Tourism, the First Year. Geogr. Plan. Space J. 2013, 3, 151–179. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B.S.; Gillen, J.; Friess, D.A. Challenging the principles of ecotourism: Insights from entrepreneurs on environmental and economic sustainability in Langkawi, Malaysia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J. Implicit theories of personal and social attributes: Fundamental mindsets for a science of wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, D.S.; Hanselman, P.; Walton, G.M.; Murray, J.S.; Crosnoe, R.; Muller, C.; Tipton, E.; Schneider, B.; Hulleman, C.S.; Hinojosa, C.P.; et al. A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature 2019, 573, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gagne, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F.A. A new approach to reducing disorder and improving well-being. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 4, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. The Contours of Positive Human Health. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V.; Ryan, R.M. Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J. Flourishing: Achievement-related correlates of students’ well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, R.; Capolongo, S. Healing environment and urban health. Epidemiol. Prev. 2016, 40, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L. Flourishing. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; Weiner, I.B., Craighead, W.E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderweele, T.J. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8148–8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; McNeely, E.; Koh, H.K. Reimagining Health—Flourishing. JAMA 2019, 321, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, B.C.S. Ingredients of a Winning Mindset. In Mindset: The New Psychology of Success; Ballentine: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S. Motivational processes affecting learning. Am. Psychol. 1986, 41, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, C.; Risavy, S.D.; Perunovic, E.; Plant, L. Do subordinates formulate an impression of their manager’s implicit person theory? Appl. Psychol. 2014, 63, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslin, P.A.; VandeWalle, D. Performance appraisal procedural justice: The role of a manager’s implicit person theory. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1694–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Leggett, E.L. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 95, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diveck, C.S.; Molden, D.C. Self-Theories: Their Impact on Competence Motivation and Acquisition; Eliot, A.J., Dweck, C.S., Eds.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Levontin, L.; Halperin, E.; Dweck, C.S. Implicit theories block negative attributions about a longstanding adversary: The case of Israelis and Arabs. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, S.P.; Kumar, J. Ecotourism for Community Development: A Stakeholder’s Perspective in Great Himalayan National Park. In Creating a Sustainable Ecology Using Technology-Driven Solutions; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Barrington-Leigh, C.; Harris, A.; Huang, H. International Evidence on the Social Context of Well-Being. In International Differences in Well-Being; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 291–327. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women Annual Report 2017–2018. Available online: https://annualreport.unwomen.org/en/2018 (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Huang, Z.; Cui, L.; Liu, S.; Fang, Y.; Ren, G.; Fornacca, D.; Xiao, W. Ecotourism in China, misuse or genuine development? An analysis based on map browser results. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, H.; Sidani, Y.M.; Baalbaki, I. United Arab Emirates female entrepreneurs: Motivations and frustrations. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2011, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechavarria, D.M.; Ingram, A.; Justo, R.; Terjesen, S. Are women more likely to pursue social and environmental entrepreneurship? In Global Women’s Entrepreneurship Research: Diverse Settings, Questions and Approaches; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, D.J.; Brush, C.G.; Greene, G.P.; Litovsky, Y. Report: Women Entrepreneurs Worldwide; Babson College and the Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GERA): London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S.L.; Anderson, S.; Shaw, E. Women’s Business Ownership: A Review of the Academic, Popular and Internet Literature; University of Strathclyde: Glasgow, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Heyzer, N. Smart development: Gender equality key to achieving the MDGs. In Proceedings of the 61st Session of the UN General Assembly, Second Committee, Agenda Item 58, New York, NY, USA, 2 November 2006; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization. 2017 Annual Report; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, J.K.; Walter, P. How do you know it when you see it? Community-based ecotourism in the Cardamom Mountains of southwestern Cambodia. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Exploring the Tourism-Poverty Nexus. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.; Hinch, T. Tourism and Indigenous Peoples: Issues and Implications; Butterworth-Heinemann: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tanova, C. Firm size and recruitment: Staffing practices in small and large organisations in north Cyprus. Career Dev. Int. 2003, 8, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven Lisaniler, F. Challenges in SME development: North Cyprus. In Workshop on Investment and Finance in North Cyprus; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Howells, K.; Krivokapic-Skoko, B. Constraints on Female Entrepreneurship in Northern Cyprus. Kadin/Woman 2000, 8, 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- Purrini, M.K. Economic Empowerment of Rural Women through Enterprise Development in Post-Conflict Settings. Expert Group Meeting “Enabling rural women’s economic empowerment: Institutions, opportunities and participation”. In Proceedings of the Kosovo Women’s Business Association, Gjakove, Kosovo, 20–23 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadani, V.; Rexhepi, G.; Abazi-Alili, H.; Beqiri, B.; Thaçi, A. A look at female entrepreneurship in Kosovo: An exploratory study. J. Enterp. Communities 2015, 9, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Gender Gap Report 2020. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Project, G.S.C. The Score For Peace. 2018. Available online: https://scoreforpeace.org/files/publication/pub_file//PB_GenderCy17_TCcPolicyBriefWeb_30052018_ID.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- DeNeve, K.M.; Cooper, H. The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 197–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F. Well-Being, Social Capital and Public Policy: What’s New? Econ. J. 2006, 116, C34–C45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Sheppard, L.D. The Yin and Yang of entrepreneurship: Gender differences in the importance of communal and agentic characteristics for entrepreneurs’ subjective well-being and performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 709–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, J.; Ferguson, L. The gender dimensions of New Labour’s international development policy. In New Labour and Women: Engendering Policy and Politics; Annesley, C., Gains, F., Rummery, K., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2007; pp. 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bystydzienski, J. Women Transforming Politics: Worldwide Strategies for Empowerment; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Sparrowe, R.T. An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relations between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Castri, F. Sustainable tourism in small islands: Local empowerment as the key factor. Int. J. Island Aff. 2004, 13, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S. Information and empowerment: The keys to achieving sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petric, L. Empowerment of communities for sustainable tourism development: Case of Croatia. Tour. Int. Discip. J. 2007, 55, 431–443. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, R. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telef, B.B. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the psychological well-being. In Proceedings of the 11th National Congress of Counseling and Guidance, Selcuk-Izmir, Turkey, 3–5 October 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Perrewé, P.L.; Hochwarter, W.A.; Rossi, A.M.; Wallace, A.; Maignan, I.; Castro, S.L.; Ralston, D.A.; Westman, M.; Vollmer, G.; Tang, M.; et al. Are work stress relationships universal? A nine-region examination of role stressors, general self-efficacy, and burnout. J. Int. Manag. 2002, 8, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.R.; Stroessner, S.J.; Dweck, C.S. Stereotype formation and endorsement: The role of implicit theories. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1421–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chem, I.; The, M.; Financial, A. R(0.86). Chart 2003, 81, 2001–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G. Measuring empowerment: Developing and validating the Resident Empowerment through Tourism Scale (RETS). Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R. A Brief Tutorial on the Development of Measures for Use in Survey Questionnaires. Organ. Res. Methods 1998, 1, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Mueller, C.W. Introduction to Factor Analysis: What It Is and how to Do It; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. The assessment of reliability. In Psychometric Theory; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Global Education Monitoring Report 2019: Migration, Displacement and Education: Building Bridges, Not Walls. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/infographics/2019-gem-report-migration-displacement-and-education-building-bridges-not-walls (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Sdino, L.; Magoni, S. The Sharing Economy and Real Estate Market: The Phenomenon of Shared Houses. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions, Bolzano, Italy, 22–24 March 2018; pp. 241–251. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).