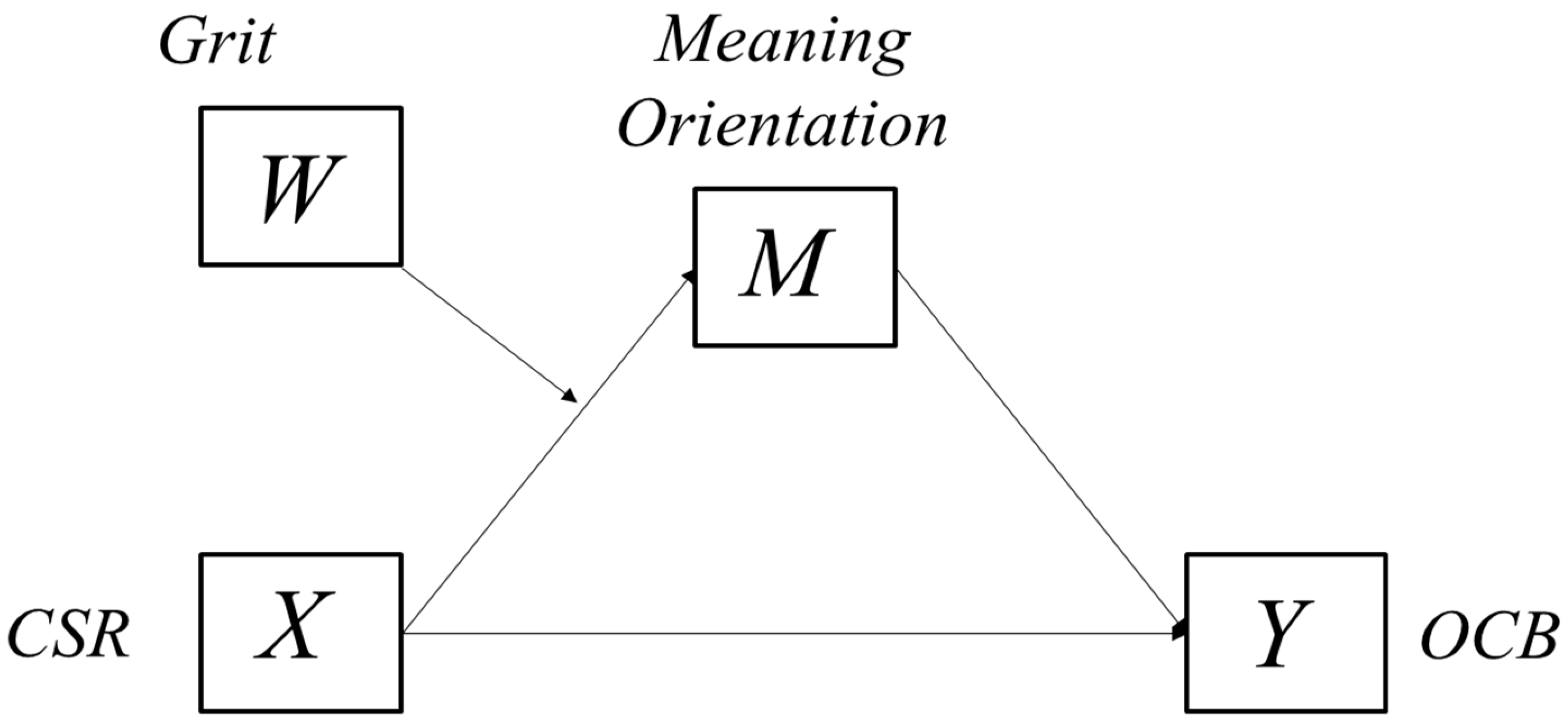

The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Grit and Meaning Orientation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Perceived CSR and OCB

2.2. Meaning Orientation as a Mediator

2.3. Grit as a Moderator

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility

3.2.2. Organizational citizenship behavior

3.2.3. Meaning Orientation

3.2.4. Grit

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

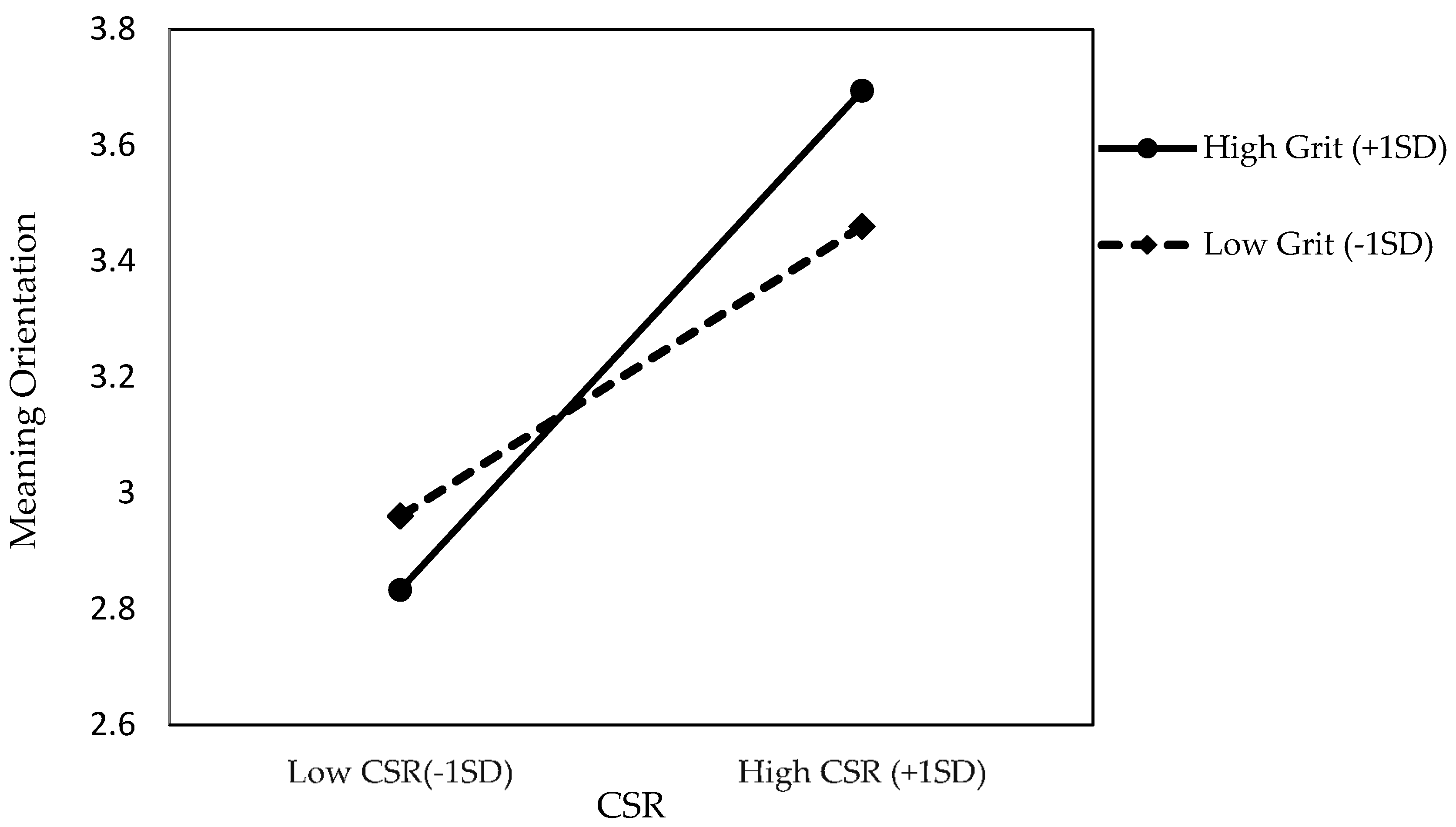

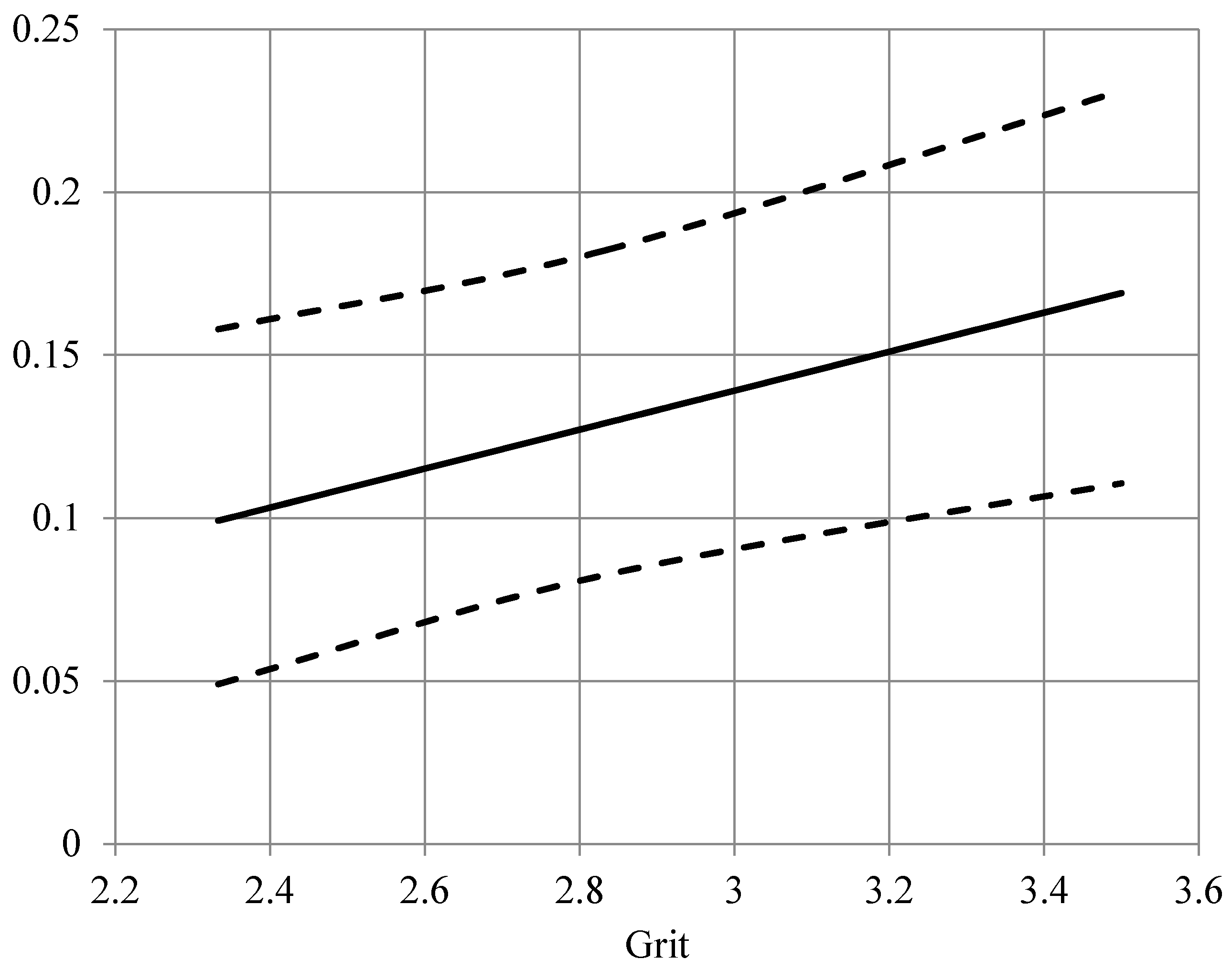

4.3. Moderated Mediation Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2013. Available online: http://www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/corporate-responsibility/Documents/corporate-responsibility-reporting-survey-2013-v2.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2015).

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J. Managing corporate sustainability and CSR: A conceptual framework combining values, strategies and instruments contributing to sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, K.; Palazzo, G. Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sensemaking. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Delobbe, N. Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. J. Mana. 2014, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Piderit, S.K. How does doing good matter? Effects of corporate citizenship on employees. J. Corp. Citizensh. 2009, 36, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D. The motivational basis of organizational behavior. Behav. Sci. 1964, 9, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, T.S.; Organ, D.W. Job satisfaction and the good soldier: The relationship between affect and employee “citizenship.”. Acad. Manag. J. 1983, 26, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. A reappraisal and reinterpretation of the satisfaction-Causes-Performance hypothesis. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1977, 2, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, W.R.; Davis, W.D.; Frink, D.D. An examination of employee reactions to perceived corporate citizenship. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 938–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z.; Saleem, Z.; Rajput, A.A. The mediating role of employee engagement between the relationship of distributive justice and organizational citizenship behavior: Empirical evidence from aviation sector of Pakistan. Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2014, 2, 494–500. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.A. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, E.Y.; Jung, H.; Park, I.J. Psychological factors linking perceived CSR to OCB: The role of organizational pride, collectivism, and person–Organization fit. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; LePine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Peterson, C.; Matthews, M.D.; Kelly, D.R. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, A. Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, Y.J.; Yang, S. On the mediating effects of grit and prosocial behavior in the relationship between intrinsic vs. prosocial motivation and life satisfaction. Korean J. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 30, 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- 2014 Von Culin, K.R.; Tsukayama, E.; Duckworth, A.L. Unpacking grit: Motivational correlates of perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Posit. Psychol. 2014, 9, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamali, D.; Mirshak, R. Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Theory and practice in a developing country context. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Profit maximizing corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2001, 26, 504–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Riaz, Z.; Arain, G.A.; Farooq, O. How do internal and external CSR affect employees’ organizational identification? A perspective from the group engagement model. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Aguinis, H.; Waldman, D.A.; Siegel, D.S. Extending corporate social responsibility research to the human resource management and organizational behavior domains: A look to the future. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 805–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. CSR and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in the hotel industry: The moderating roles of corporate entrepreneurship and employee attachment style. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2867–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb Chowdhury, D. Organizational citizenship behavior towards sustainability. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Soc. Sci. (IJMESS) 2013, 2, 28–53. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/71156 (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Nielsen, T.M.; Hrivnak, G.A.; Shaw, M. Organizational citizenship behavior and performance: A meta-analysis of group-Level research. Small Gr. Res. 2009, 40, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Give and Take: Why Helping Others Drives Our Success; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Allen, N.J. Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Colquitt, J.A. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Acad. Manage. J. 2006, 49, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ion, A.; Mindu, A.; Gorbănescu, A. Grit in the workplace: Hype or ripe? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2017, 111, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Shin, Y.; Park, J.; Sohn, Y. Effects of grit on organizational citizenship behavior: Mediating roles of job positive affect and occupational self-efficacy. Korean J. Ind. Org. Psychol. 2018, 31, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. Justice and organizational citizenship: A commentary on the state of the science. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1993, 6, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.H.; Moon, T.W.; Hur, W.M. Bridging service employees’ perceptions of CSR and organizational citizenship behavior: The moderated mediation effects of personal traits. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boezeman, E.J.; Ellemers, N. Pride and respect in volunteers’ organizational commitment. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S. A matter of reputation and pride: Associations between perceived external reputation, pride in membership, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Br. J. Manag. 2013, 24, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Farid, T.; Iqbal, S.; Ma, J.; Castro-González, S.; Khattak, A.; Khan, M.K. Employees’ perceptions of CSR, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effects of organizational justice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulin, C.L. Work and being: The meanings of work in contemporary society. In The Nature of Work: Advances in Psychological Theory, Methods, and Practice; Ford, J.K., Hollenbeck, J.R., Ryan, A.M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Raub, S.; Blunschi, S. The power of meaningful work: How awareness of CSR initiatives fosters task significance and positive work outcomes in service employees. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V.E. Man’s Search for Meaning; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C.; Park, N.; Seligman, M.E. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. J. Happiness Stud. 2005, 6, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Lim, J. The validation of the Korean version of the orientations to happiness questionnaire for Korean college students. Korean J. Hum. Dev. 2013, 20, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Supanti, D.; Butcher, K. Is corporate social responsibility (CSR) participation the pathway to foster meaningful work and helping behavior for millennials? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1982, 33, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M. Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 517–554. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, C.; Madden, A. What makes work meaningful-or meaningless? MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2016, 57, 53–61. Available online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/61282 (accessed on 11 September 2019).

- Gully, S.M.; Phillips, J.M.; Castellano, W.G.; Han, K.; Kim, A. A mediated moderation model of recruiting socially and environmentally responsible job applicants. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 935–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.R.; Matthews, M.D.; Bartone, P.T. Grit and hardiness as predictors of performance among West Point cadets. Mil. Psychol. 2014, 26, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Quinn, P.D.; Seligman, M.E. Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. J. Pos. Psychol. 2009, 4, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson-Kraft, C.; Duckworth, A.L. True grit: Trait-Level perseverance and passion for long-term goals predicts effectiveness and retention among novice teachers. Teach. Coll. Rec (1970) 2014, 116. Available online: http://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentId=17352 (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. Construal Level Theory of Intertemporal Judgment and Decision; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, K.; Sasota, J.A. The effects of construal levels on asymmetric temptation-goal cognitive associations. Soc. Cogn. 2011, 29, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, A.; Sohn, Y.; Lee, S. The power of achieving long-term goal: Characteristic of the gritty people based on future time perspective. Korean J. Soc. Pers. Psychol. 2019, 33, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Sung, M. The influence of employee’s perceived CSR on their organizational citizenship behavior. J. Public Relat. 2018, 22, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, D.; Judd, C.M.; Yzerbyt, V.Y. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Suh, D. Assessing Mediated Moderation and Moderated Mediation: Guidelines and Empirical Illustration. Korean J. Psychol. 2016, 1, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using multivariate statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, R.; Gore Jr, P.A. A brief guide to structural equation modeling. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 719–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process. Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monog. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LG Business Insight 2013. Available online: http://www.lgeri.com/report/view.do?idx=18004 (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Schneider, B. The people make the place. Pers. Psychol. 1987, 40, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G.Q.; Karadag, E. Generational differences in work values and attitudes among frontline and service contact employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimkiewicz, K.; Oltra, V. Does CSR enhance employer attractiveness? The role of millennial job seekers’ attitudes. CSR Envir. Manag. 2017, 24, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.; Kim, M.; Jeong, S.; Huh, K. Causes and remedies of common method bias. Korean J. Manag. 2007, 15, 89–133. [Google Scholar]

| Model | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Model (four factors) | 3.69 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Alternative Model (three factors | 7.56 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Alternative Model (two factors | 7.38 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Alternative Model (one factor | 6.11 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 28.74 | 13.61 | - | ||||||

| 2. Tenure | 3.24 | 1.08 | ** | - | |||||

| 3. Job Rank | 2.49 | 1.53 | ** | ** | - | ||||

| 4. Organization Size | 2.92 | 1.39 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 | - | |||

| 5. CSR | 2.76 | 0.84 | ** | ** | ** | ** | - | ||

| 6. Grit | 2.90 | 0.61 | ** | ** | ** | 0.01 | 0.09 | - | |

| 7. Meaning Orientation | 3.24 | 0.68 | ** | 0.10 | ** | 0.07 | ** | ** | - |

| 8. OCB | 3.35 | 0.56 | ** | ** | ** | 0.06 | ** | * | ** |

| Variable | OCB | Meaning Orientation | OCB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | b | t | |

| CSR | 0.36 | *** | −0.12 | − *** | 0.22 | *** |

| Meaning Orientation | 0.35 | *** | ||||

| Grit | −0.43 | − ** | ||||

| CSR × Grit | 0.17 | ** | ||||

| Gender | −0.15 | − * | −0.03 | −0.38 | −0.14 | − ** |

| Age | 0.01 | *** | 0.00 | 1.57 | 0.01 | ** |

| Tenure | 0.01 | 0.235 | −0.06 | −1.89 | 0.03 | 1.22 |

| Job Rank | 0.03 | 0.154 | 0.07 | * | 0.01 | 0.31 |

| Organization Size | −0.36 | − * | −0.01 | −0.41 | −0.03 | − * |

| Conditional Indirect Effect | Boot SE | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI | |||

| High Grit (+1SD) | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.16 | ||

| Low Grit (−1SD) | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.23 | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, J.; Sohn, Y.W.; Lee, S. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Grit and Meaning Orientation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5411. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135411

Choi J, Sohn YW, Lee S. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Grit and Meaning Orientation. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5411. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135411

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Jinsoo, Young Woo Sohn, and Suran Lee. 2020. "The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Grit and Meaning Orientation" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5411. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135411

APA StyleChoi, J., Sohn, Y. W., & Lee, S. (2020). The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Grit and Meaning Orientation. Sustainability, 12(13), 5411. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135411