1. Introduction

The growth and expansion of metropolitan areas is a worldwide phenomenon. An increasing percentage of the world’s population (currently 55%) is living in urban areas, and the world’s urban population is expected to surpass 6 billion people, around 68% of the global population, in 2050 [

1]. This growth brings important challenges for sustainable urbanization as social, environmental and economic living conditions in many urban regions are under pressure [

2]. In this context, urban food security, environmental sustainability and the well-being of the urban population are seen as key factors to successful urban development [

3].

With the adoption of the United Nations’ New Urban Agenda in 2016, a new global standard for sustainable urban development has been set [

3]. Among other things, this New Urban Agenda urges national governments and local authorities to provide nutritious food to all their citizens. Current issues with urban food security relate to both the quantity and quality of available food [

4,

5]. Issues such as malnutrition, obesity, hunger, nutrient deficiencies and the affordability of good quality food are important topics in this context, but environmentally sustainable food production and a reduction of food waste are also of key relevance [

3,

5]. Food and nutrition security is a multidimensional concept and the definition has four dimensions: (i) the

availability of food; (ii)

accessibility of food markets; (iii) food

utilization, which is includes the nutritional value, social value and food safety; and (iv) the

stability of food security over time [

6]. The urban aspects of food security have not received much attention yet, especially in low- and middle-income countries [

7,

8].

Over recent years, several initiatives have taken place in order to promote a more sustainable urban food system. A prominent example is the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. In this pact, more than 180 cities and regions from all over the world have committed to developing sustainable food systems which provide healthy and affordable food to all people while minimizing waste and biodiversity loss [

9]. At the UN Habitat III meeting on sustainable urban development in 2016, many organizations and countries put food security high on the agenda and urged for action to promote this security [

10]. Various European cities are now taking up a proactive role in urban food system transformations, as presented at the Fifth Annual Gathering and Mayors’ Summit of signatory cities in Montpellier (France), November 2019. These developments encourage transitions towards a more sustainable development of metropolitan areas with access to safe and nutritious food.

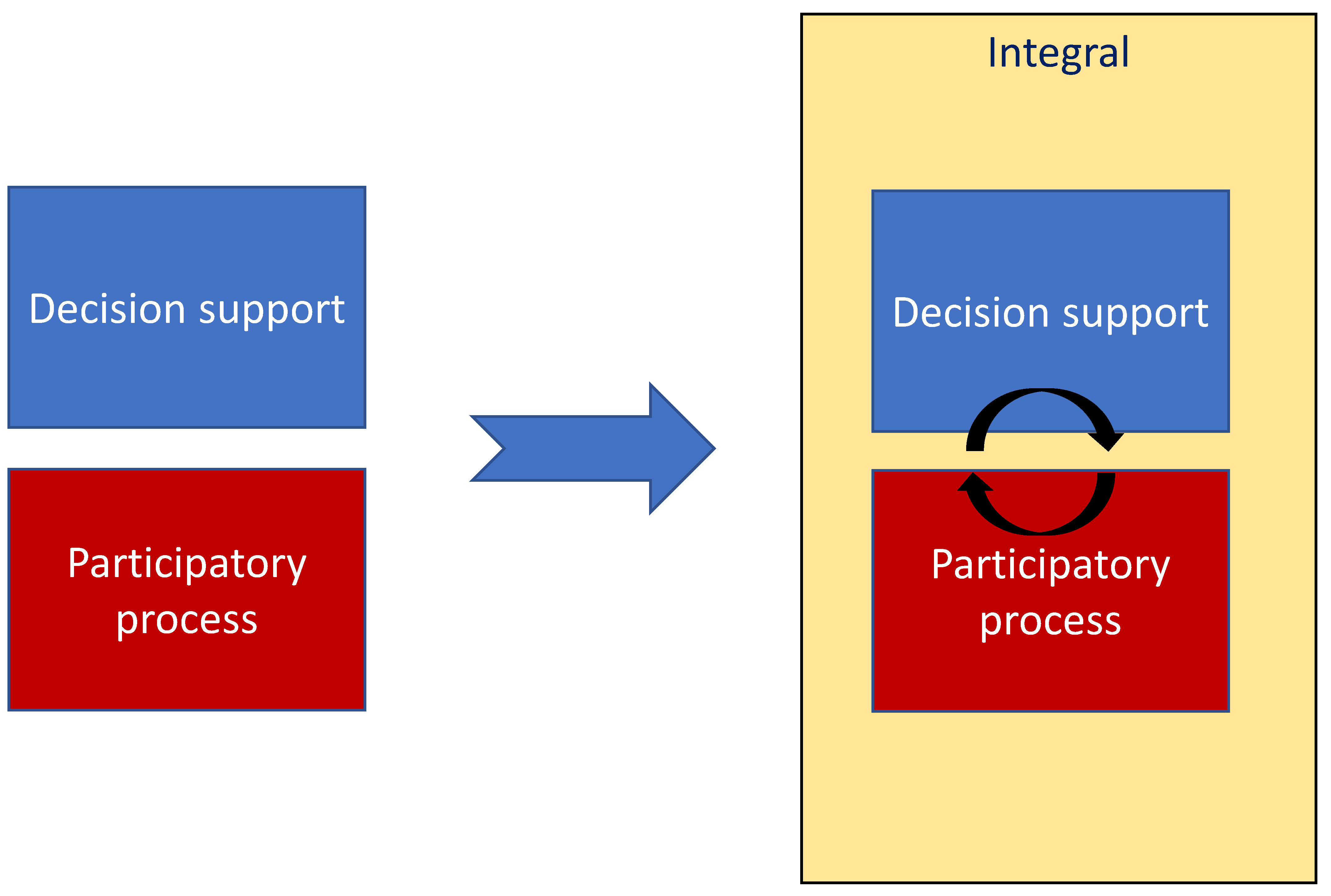

The main aim of this article is to contribute towards urban food security in metropolitan areas by combining the need for stakeholder participation in model-driven decision support to develop transition pathways [

11,

12]. For this purpose, we will present a stakeholder-inclusive approach to decision making in food system transitions: the Transition Support System (TSS) approach. In this TSS approach, decision support tools and participatory processes are mutually employed to support urban food security. As we will show in this article, there are important benefits to combining stakeholder-based and modeling-based methods in promoting food system transitions contributing to better informed decision making in a dynamic context where unforeseen factors and new priorities of stakeholders can be included. Our TSS approach also aligns with the UN’s New Urban Agenda, which envisages an involvement of stakeholders in transformation of the urban food system.

Section 2 introduces the materials and methods which form the basis of this article. This is followed by

Section 3, which introduces the main points of departure for our TSS approach. Based on the literature, a number of important principles for this approach are identified and discussed, and based on these, the TSS approach is introduced.

Section 4 discusses the practical applications of this approach as a process of small steps.

Section 5 will explain how the TSS approach has been used in practice and showcase its employment in two case studies. This article is wrapped up with a discussion and conclusion in

Section 6.

2. Materials and Methods

The material presented in this article is based on a study of the literature and discussions with stakeholders and experts, as well as on an empirical application of the TSS approach in two case studies. This research was not implemented through a systematic and linear process, but should rather be seen as an iterative exercise where lessons from literature, workshops and stakeholder feedback were employed in order to develop and improve the Transition Support System approach which we will present in the following sections.

First, an integrative study of literature was conducted. In contrast to a structured review of literature, this type of study does not aim to systematically cover all articles ever published on a certain topic or within a certain field of research. Rather, it aims to combine and integrate perspectives and insights from different scientific domains or research traditions [

13]. For such purposes, a strict and structured approach can hinder a more creative, cross-cutting, conceptual and integral contribution. In this context, an integrative study of literature is preferable [

13]. Such a study of literature should advance conceptual or theoretical frameworks instead of providing an overview of a research area. This often demands a more creative and flexible collection of data in comparison to a structured review of literature [

13].

In this way, rather than providing a systematic overview of literature on urban food security or stakeholder inclusion in transitions, our work in this article presents a meta-narrative which identifies a number of main building blocks for promoting urban food security (

Section 3) and develops this into a conceptual and methodological framework (

Section 4). Relevant literature was identified through a search in scientific databases (Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science) and also collected via colleagues and peers. Following the broad scope of this integrative study, the literature was not collected through fixed sets of keywords, but by exploring many different topics and research domains. Based on this initial collection of literature, a snowball method was also applied to collect additional information via references cited in the articles that were initially collected.

The TSS approach was applied and tested in two contrasting case studies presented in

Section 5. The purpose of these case studies is to show the applicability of the approach in real life situations [

14]. Including more cases was beyond the aim of illustrating applicability and would also provide less space for in-depth analysis and description in this article. One case was employed in the Dutch province of Overijssel and the other in the metropolitan region of Accra (Ghana). The Overijssel case was established because the policy-makers of the densely populated province of Overijssel were searching for innovative ways to improve the sustainability of the agricultural sector in the province (reducing greenhouse gas emissions in a Western European country). In the Accra case, earlier research projects had indicated the huge challenges that Ghana faces with the high degree of urbanization of its capital, Accra in a developing context [

15,

16], and this was followed up by the case study described in

Section 5.

As the inclusion of stakeholders in both cases was part of the research experience, we will provide more details on this process as part of the elaboration of the TSS approach in

Section 3 and

Section 4. In

Section 5, we will explain which stakeholders were involved throughout the process and in what way they were involved. In both case studies, co-creation meetings with stakeholders were organized depending on the issues at stake in the period 2017–2019.

4. The TSS Approach: A Transition Process in Small Steps

The process of the Transition Support System approach is illustrated in

Figure 2. This figure is built upon the principles introduced in the previous section: approaching food system transformation from an integral, multi-stakeholder perspective; a combination of decision support tools and stakeholder participation in knowledge processes; and an interactive involvement of stakeholders throughout different phases of the governance process.

At several points during this process, scientific knowledge and social or technological innovations are discussed and debated with stakeholders, generally aided by the use of decision support tools. The agenda at stake is regularly updated in order to reflexively adapt to unforeseen factors and new priorities from stakeholders. During this process, stakeholders can join or leave at any given time and—depending on issues at stake—different decision support tools can be employed in order to underpin the developments and impacts of interventions. Discussions with stakeholders provide input to scientists and policy-makers that can help them in developing solutions that promote urban food security but are also embedded in society. This is an ongoing circular process of small steps during different stages of an ongoing transition. Eventually, after a longer period of time, this process should lead to sustainable food secure metropolitan solutions.

The methods and tools employed in our TSS are not set in stone: different food systems in varying socioeconomic contexts might require different approaches and different tools. Generally speaking, however, each iteration of the TSS consists of five steps (

Figure 3). These steps all involve relevant stakeholders and should be continuously and iteratively conducted: step five is again followed by step one to work towards a secure urban food system in a stepwise and iterative manner.

4.1. Determine Urgency

The New Urban Agenda [

3] and Milan Urban Food Policy Pact [

9] both stress the importance of food system transformation in the city. In order to involve stakeholders in this transformation, there needs to be a sense of urgency amongst them—otherwise, why would they participate? The starting point for applying the TSS should therefore lie with identifying relevant topics that provoke a shared sense of urgency amongst stakeholders. This does not mean that these stakeholders need to have a shared agenda, but they should be motivated to address this topic. Pressing issues in the urban food system can be identified and addressed in consultancy with various public and private stakeholders and cover various topics. For answering such questions, an evaluation of policy, societal trends and the position of relevant stakeholders is important. On the basis of such an analysis, a broader group of stakeholders can be identified and invited to engage in the TSS process.

4.2. Scenario Analysis

To progress from a sense of urgency towards a (shared) vision for food secure cities, deliberation with stakeholders is of vital importance [

34]. In this, stakeholder-based scenario, analyses can lead to a better understanding of the issues at stake and open up discussions about potential futures and the changes that are required to come to a new urban food system [

47]. In this second step, several scenario-based decision support tools can therefore be used to gain insight into potential futures [

31] and facilitate discussions about desired views. By projecting different options and analyzing scenarios, the desirability of future developments can be discussed with stakeholders, including an assessment of potential courses of action towards their ideal futures.

4.3. In-Depth Analysis

In order to progress from a vision of desirable futures towards an assessment of the potential impacts of various courses of action, a variety of models can be employed in various spatial analyses. With such analyses, decision support tools are used to spatially and/or numerically project various visions of the future [

31]. While this step is strongly rooted in expert-based modeling, this should form the basis for a deliberation with stakeholders as it provides valuable information about the issues at stake and future perspectives in regard to these issues. For such an in-depth analysis, a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods and techniques should be employed, also tailored to the spatial scale (national, regional or local) on which urgencies have been identified. The aim should be to maximize complementarity between different types of knowledge and better link stakeholders’ priorities and policy objectives with quantitative models [

32]. This step should provide insight into diverse scenarios for the future, for example: how does growth of the urban population influence the demand for and production of food and what effects does this have on food prices?

4.4. Insight into Future Pathways (Chosen Strategy and Policy)

After the in-depth analysis, the next step should provide visual insight into the effects of different courses of action in order to contribute towards stakeholders’ understanding of the impacts of such actions. As discussed previously in this article, transitions are difficult to steer and predict as they are complex, long-term processes [

21,

22]. Visualizing the potential outcomes of different courses of action can help stakeholders to obtain a better grasp on these issues and discuss the complex interlinkages between different factors. Again, this should form the basis of an interactive discussion: in a set of meetings, points of departure for urban food security and the potential of certain interventions or actions can be discussed with stakeholders, supported by the analysis in the previous steps in which the potential effects of certain actions have been projected. Jointly, it can then be debated which effects are desirable, which other impacts might be associated with this, and whether other courses of actions are preferable. This can lead to a shared action perspective and a potential fine-tuning of, or change in, the models and data that are part of the decision support in order to adequately address these priorities.

4.5. Impact Evaluation

After the impact of certain actions has been projected ex-ante, it is important to also monitor the effects or interventions during and after these have been employed. After all, aiming for societal change requires constant evaluation and adaptation in governance [

34]. For this reason, it is important to closely monitor the ongoing changes that are taking place in the urban food system so that policies and actions can be adapted [

41]. In this fifth step, chosen strategies and changing policies will be evaluated together with stakeholders: what are the experienced and measured consequences of actions and how do these effects relate to the projected and desired impacts? The feedback provided by stakeholders in this step also links back to the decision support tools: how can these tools be used and improved to promote urban food security and help in coming to new spatial insights and effects? During the evaluation, new urgencies and issues can be discussed with stakeholders for a new iteration of the TSS approach until, eventually, the desired urban food security impacts have been realized.

5. Results

The TSS approach has been applied in two case studies. The main purpose of this is to show the applicability of the TSS approach. Given that the TSS approach is relatively new, we have not been able to explore a transition process from the beginning to the end, if such a beginning or end could even be pinpointed. Because transition processes typically take many years, our own reporting of such a transition should also be an iterative process with multiple iterations over time, in line with principles from the TSS approach.

5.1. Sustainable Food System for Urban Areas in Overijssel (The Netherlands)

Overijssel is a province with 1.1 million inhabitants in the eastern part of The Netherlands. About half of the population lives in the five major cities of the province, spread across three large urban regions: Almelo, Deventer, Enschede, Hengelo, and Zwolle. While the province is quite densely populated, Overijssel is known for its agricultural landscape. More than 70% of the rural area is used for agriculture, which illustrates the high spatial impact of this sector. While the three urban networks are the driving forces behind the regional economy, the agricultural and food sector are important economic pillars and account for 10.0% of the regional GDP and 6.8% of regional employment. Climate change, ambitions for promoting livable and healthy cities, and challenges for sustainable food provision in these cities are cited by policy-makers as important motives to change the current food system. In the provincial future vision for the physical environment for 2030, the importance of a sustainable food system which remains competitive is highlighted [

48].

The TSS approach has been employed in order to discuss the road towards such a food system. Together with representatives of the province Overijssel, the involved researchers identified and selected the relevant stakeholders based on their position within the food system. Based on this initial analysis, representatives of the province of Overijssel, farmers, food processing industries, NGOs and citizens were invited for three sessions which were organized in November 2017, July 2018, and October 2018. For each session, different stakeholders were involved based on their interests and knowledge. Discussions during these sessions were focused on reducing regional agricultural production, fewer international transport movements, less environmental pressure, changing cropping patterns, and healthier diets.

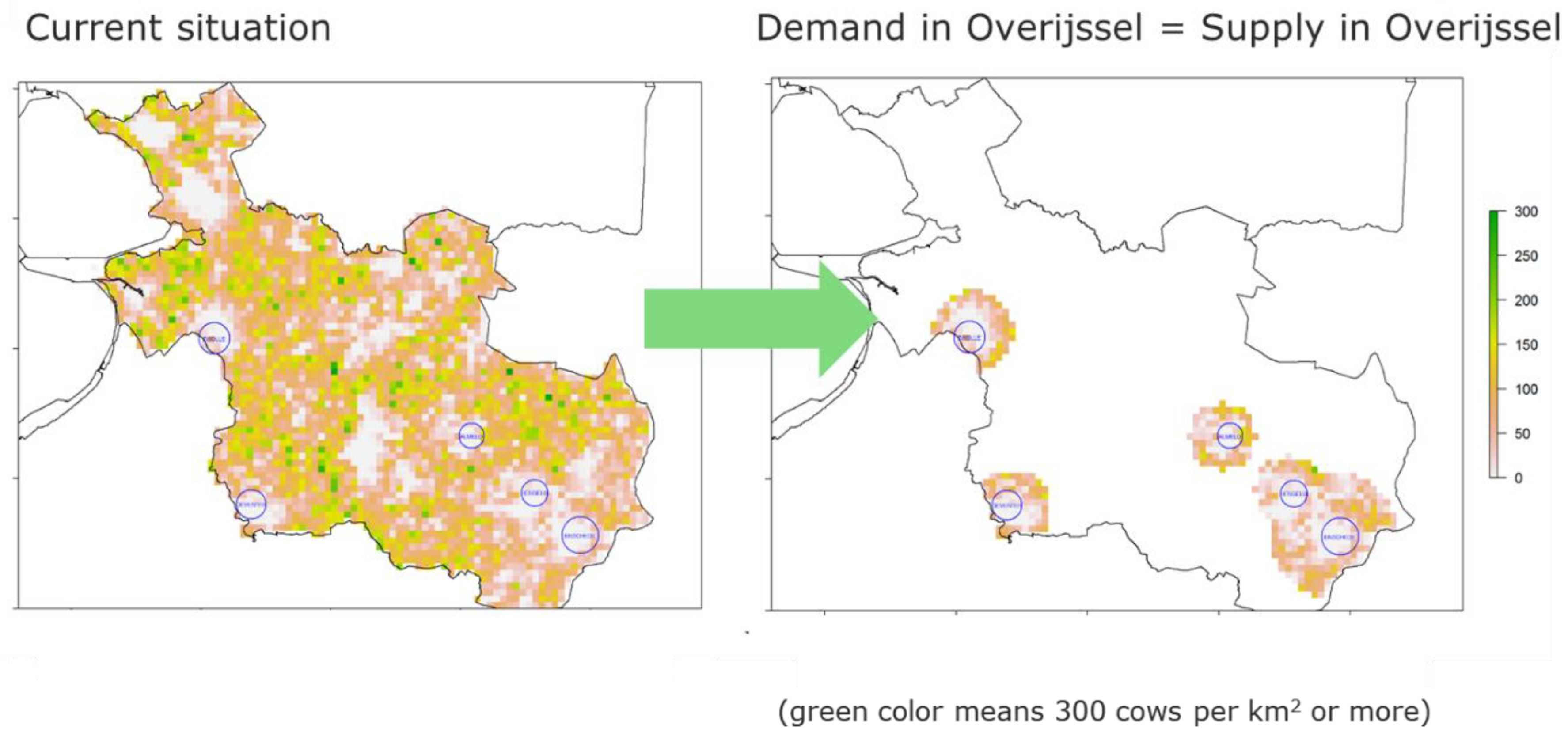

During the first meeting in November 2017, global scenarios were translated by the stakeholders into a provincial future vision for 2050 in which the supply of dairy products would equal the provincial demand (no export). Potential action perspectives towards this future were identified and discussed with stakeholders. During the second meeting in July 2018, these action perspectives were made transparent by the researchers through the use of virtual production maps (see example

Figure 4, see for more details on databases and software use [

27]). These maps provided insight into the potential spatial, environmental and economic effects of action perspectives and formed the basis for further discussion during the workshop. During this meeting, stakeholders expressed that they preferred an integral system approach towards sustainable food production instead of a sector-by-sector approach. Furthermore, a switch from actual consumption towards a healthy consumption pattern was preferred for the provincial future vision. These findings were further explored and translated into future pathways in the third meeting in October 2018.

In the current situation, dairy products are produced all over the province of Overijssel (see

Figure 4). Most of these products are exported to the rest of the Netherlands or abroad. If the dairy sector in Overijssel would only produce what is demanded in the urban areas, the herd of dairy could be reduced by approximately 80%. The production of greenhouse gas emissions from dairy would then reduce with an approximately similar percentage.

This case shows that stakeholder meetings for transitions can be dynamic with respect to the opinions and input of stakeholders. By linking spatial decision support tools with stakeholder participation, the scope and focus of the discussions as well as the employment of decision support tools shifted over time. Departing from a sectoral perspective on sustainable dairy production, the scope of discussion eventually broadened towards a more integral perspective with a focus not only on spatial, economic and environmental dimensions, but also on healthy consumption. Stakeholders contributed when the topic of a meeting linked up with their interest. Although switching participation of stakeholders was a point of concern for the continuity of discussion, stakeholders appreciated that experts at different levels—from consumer to producer—were involved and gave input during the workshops.

5.2. Urban Food Security in Accra, Ghana

In Ghana, food security has been an important topic of discussion in rural as well as in urban areas. In the metropolitan region of Accra there is high dietary diversity but low consumption of foods rich in micronutrients, such as fruits and milk and other dairy products—especially among women, poor households and the non-educated [

49]. In 2000, 32% of households’ budget in Accra was spent on food, and in poorer neighborhoods, this share was even higher [

50]. Moreover, the low quality of the food sold and lack of hygiene during food preparation and sale can contribute to food insecurity [

51].

Due to both rapid urbanization and climate change, improving future food security in Ghana will lead to new challenges in urban areas [

52]. It is projected that there will be a major urbanization trend in Ghana, which implies migration from rural to urban areas and a rapid growth of the population of Accra, which had 4 million inhabitants in 2017. Moreover, the agricultural production is expected to suffer from climate change impacts, with land potentially becoming unusable for agricultural practices [

53]. This combination of developments raises concerns about the future food security in the metropolitan area of Accra.

Employing the TSS approach, a meeting with regional experts on urban food security was organized in November 2018 in order to explore what the most issues were in the Accra metropolitan area. This included a discussion of future projections of different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) developed by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). An example of this is the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) approach from IPCC [

54]. With the global economic model MAGNET (Modular Applied GeNeral Equilibrium Tool) [

15,

16], different future projections of demographics, food production, food demand and food security in Ghana and in Accra in particular were explored.

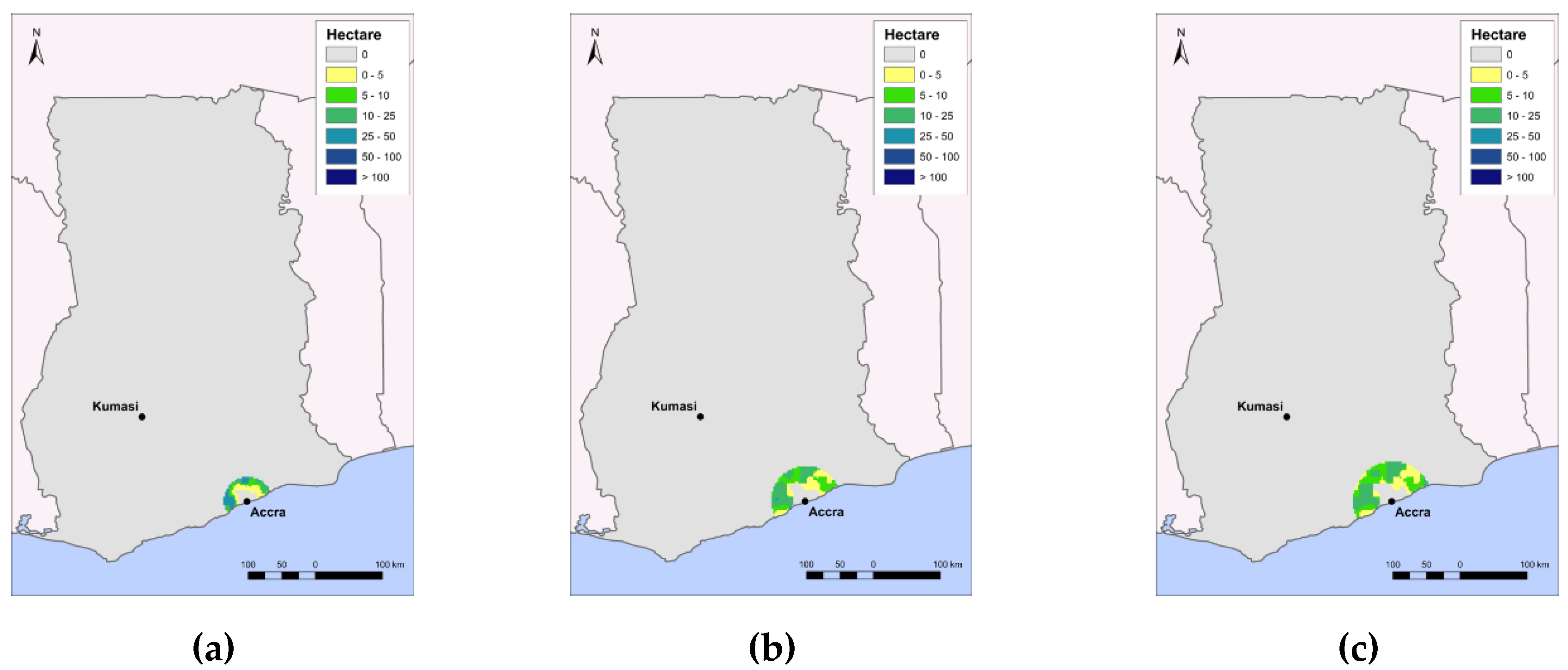

To explore this food security, two food commodities were selected: (i) vegetables and fruit (including nuts), which are advocated for their nutritional values and are widely cropped in Ghana; and (ii) rice, which is one of the dominating cereals in the diet of Ghana’s population. The main issue for urban food security is how the consumption of these commodities will develop under different scenarios and whether Ghana can stay self-supporting with respect to their production of these commodities. This was explored through virtual production maps based on the results of projections with the global economic model MAGNET, see for more details on databases and software use [

55].

The virtual production maps of Accra were obtained with an iterative procedure to search for production areas in the vicinity of Accra, so that supply of commodities would meet the demand in the Accra area.

Figure 5 shows an example of vegetable and fruit production projections under the Ecotopia scenario in 2010, 2030 and 2050 [

55]. In 2010, the virtual production circle of vegetables and fruits for a self-sufficient greater Accra was a 35 km radius (area of 56,900 ha and 5.9 million people living in this circle). With time, the area required to suffice the demand for vegetables and fruit in greater Accra under the Ecotopia scenario increased gradually. In addition, the area for fruit and vegetables production per grid cell decreases as the areas are turning increasingly green from panel (a) to (c) in

Figure 5—see [

55] for more elaborated analyses.

In the expert meeting these maps were discussed. As the experts were traditionally involved in value chain analysis of particular commodities and not food consumption and diets, these maps were new. Experts shared their knowledge and experiences within the perspective of future projections. With the experts, it was discussed what would be the most desirable future from the food security perspective, and how the transition to this future could be addressed by a broader groups of stakeholders.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Metropolitan areas are highly complex systems where safeguarding food security is not merely a shift in consumer preferences or in food production but encompasses a systematic change in the whole food chain from the primary producer up to the end-consumer [

26]. In this article, we have introduced the Transition Support System approach to identify action perspectives that can contribute towards establishing sustainable food security in metropolitan areas. The TSS approach does not provide readily available solutions for improving urban food security, but rather advocates the involvement of both stakeholders and experts in the process of looking for these solutions. It therefore promotes a stakeholder-inclusive approach to decision making in food system transitions. In order to do so, decision support tools and participatory processes are mutually employed to support moving towards urban food security. This transition is a complex, long-term process that involves many stakeholders.

6.1. Employing the TSS Approach

We have applied the TSS approach in two food system case studies with contrasting contexts: Accra (Ghana) and the province of Overijssel (the Netherlands). While both cases represent a complex situation in the early stages of a potential transition process, they illustrate how a combination of expert knowledge and decision support can contribute towards the development of new and innovative perspectives on urban food security. As a transition arises through a combined effort of diverse actors within and outside of formal boundaries, the involvement of stakeholders in processes of societal change has helped to build a joint agenda towards the future, but also in better understanding of the issues at stake by both stakeholders and scientific experts. The latter is in line with findings by Metzger et al. that highlighted how such interaction provides policy-makers and stakeholders with guidance for policy development, planning and management [

47].

The application in two contrasting case studies (Overijssel in the Netherlands and Accra in Ghana) confirmed the need to start the TSS approach with developing awareness and the added value of mapping the urgency of pressing issues on food security. This helped to identify a group of stakeholders who were invited to engage in the TSS process—and most of them responded positively. This positive response of many stakeholders as well as their contributions in different sessions emphasize that they indeed worried about urban food security. However, the involvement of stakeholders requires somebody to take the initiative and organization in order to establish a joint discussion and progress from this into an ongoing process to promote urban food security. The challenge in this is to combine central steering with an “open structure” where stakeholders feel invited and motivated to participate and bring in their own ideas: a combination of “bottom-up” and “top-down”—something for which both authorities and stakeholders are searching in urban governance [

56].

To progress from a sense of urgency towards a vision for food secure cities, the application of several scenario-based tools helped to provide valuable insight into people’s views of the desired future. To advance from these visions of desirable futures towards an assessment of the potential impacts of various scenarios, spatial analyses through a variety of models supported stakeholders. In both cases, the benefit of employing decision support models was clearly experienced during discussions. The possibility to work with these models in a live setting provided tailor made visual insights for stakeholders into the effects of different courses of action, which contributed towards their understanding of the impacts of such actions. The case studies were in the initial phase of a potential transition. In needs to be kept in mind that it is important to also monitor the effects or interventions during and after these have been employed in practices. This will allow to adapt the strategy in the future, since aiming for societal change requires constant evaluation and adaptation in governance [

39].

Regarding the specific lessons offered by these case studies, we want to emphasize that the case studies are unique and somewhat contrasting in nature. The case studies do offer important lessons and they illustrate how the TSS approach can be employed, but what works in one specific context does not necessarily do so in another. Therefore, our TSS approach can be applied elsewhere, although the local or regional context and needs of stakeholders involved should always be the point of departure. In line with principles propagated by scholars in reflexive evaluation and transition management, transferability thus requires flexibility, reflexivity and sensitivity to the local context [

20,

32,

36].

6.2. A Comparison of the TSS Approach with Other Approaches to Steer Societal Transitions

On a meta-level, a comparison of the TSS approach vis-a-vis a number of other approaches that aim to steer complex societal transitions reveals a number of parallels and distinctions. Like reflexive evaluation and transition management, the TSS approach does not depart from a linear perspective on societal transitions. Rather, it recognizes that the pathway towards such a transition is complex and that steering towards societal change is an iterative process. Concerning the research methodologies which the TSS approach employs, it integrates a “traditional” decision support perspective with stakeholder participation and deliberation from a qualitative perspective. These stakeholders are actively involved in the process of research as advocated by scholars in the fields of reflexive evaluation and transition management. As in reflexive evaluation and in some applications of transition management, scientists play a role in facilitating this interaction, but also in providing decision support that is closely linked with stakeholder expertise.

Our TSS approach is thus closely related to various aspects that are emphasized in transition management, reflexive evaluation and decision support tools, but it also has a number of distinctive features in relation to each of these approaches. The focus on decision support adds a data driven perspective which projects the impact of certain courses of action or policy decisions, providing a guidance to stakeholders as well as valuable input for discussion. By incorporating the iterative and step-wise process of joint innovation and reflection which is central in reflexive evaluation, it adds a focus on joint learning as a pathway to knowledge creation and adoption of solutions for urban food security in comparison to decision support tools and transition management. Finally, the integral scope, multi-method perspective and focus on stakeholders as innovators, all emphasized in transition management, contribute towards an action perspective for promoting urban food security through the engagement of scientists as well as stakeholders, something which is lacking in decision support tools and that broadens the methodological scope of reflexive evaluation.

6.3. Towards Urban Food Security

In line with observations by others, the above two case studies have illustrated that societal change towards food security is a non-linear, iterative, multi-stakeholder process in which diverse societal forces come together [

20,

21]. The literature has highlighted how stakeholders struggle to significantly affect the city and the urban environment as a whole in order to promote societal change [

57]. It has also been shown how authorities are still searching for proper ways to connect to various stakeholders and “steer” the fragmented efforts of societal actors towards a more structural transition [

56,

58]. Since a transition arises through a combined effort of diverse stakeholders, the issue of urban food security demands authorities and scientists to engage with a broad range of stakeholders in order to address and promote potential solutions.

Our TSS approach provides inspiration for how this can be done, but should not be seen as a strict framework to be applied “as is”: it is important to incorporate the preferences of stakeholders in organizing the governance process and tailor the employment of decision support tools to the local context. Those employing the TSS or other frameworks to promote urban food security need to do so with a degree of flexibility in order to tailor research to the preferences of stakeholders, the political and ecological context, and the specific food security issues at stake.

In this, our review of the literature in

Section 3 as well as our empirical work in

Section 5 of this article have illustrated that a combination of stakeholder-based and science-based methods is necessary in order to link scientific knowledge on food security with stakeholder aims and expertise, promoting sustainable transitions that are better embedded in society. Promoting a transition in the urban food system requires joint learning and reflexive evaluation in order to adapt governance to what is happening in society. In promoting urban food security, we strongly believe that research institutes should go beyond their role as merely “suppliers of knowledge”, but also have a role as a supporting actor in a broader process of change, engaging with a variety of societal stakeholders. After all, we as scientists are but one of many actors who have a stake in the urban food system. Working together with farmers, farm advisors and suppliers, NGOs and citizen groups, brokers, retail-stores, food transporters, food consumers, and authorities can also help us to better understand the issues at stake, promote tailored solutions and increase the impact of our work.