Effect of Work Environment on Presenteeism among Aging American Workers: The Moderated Mediating Effect of Cynical Hostility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

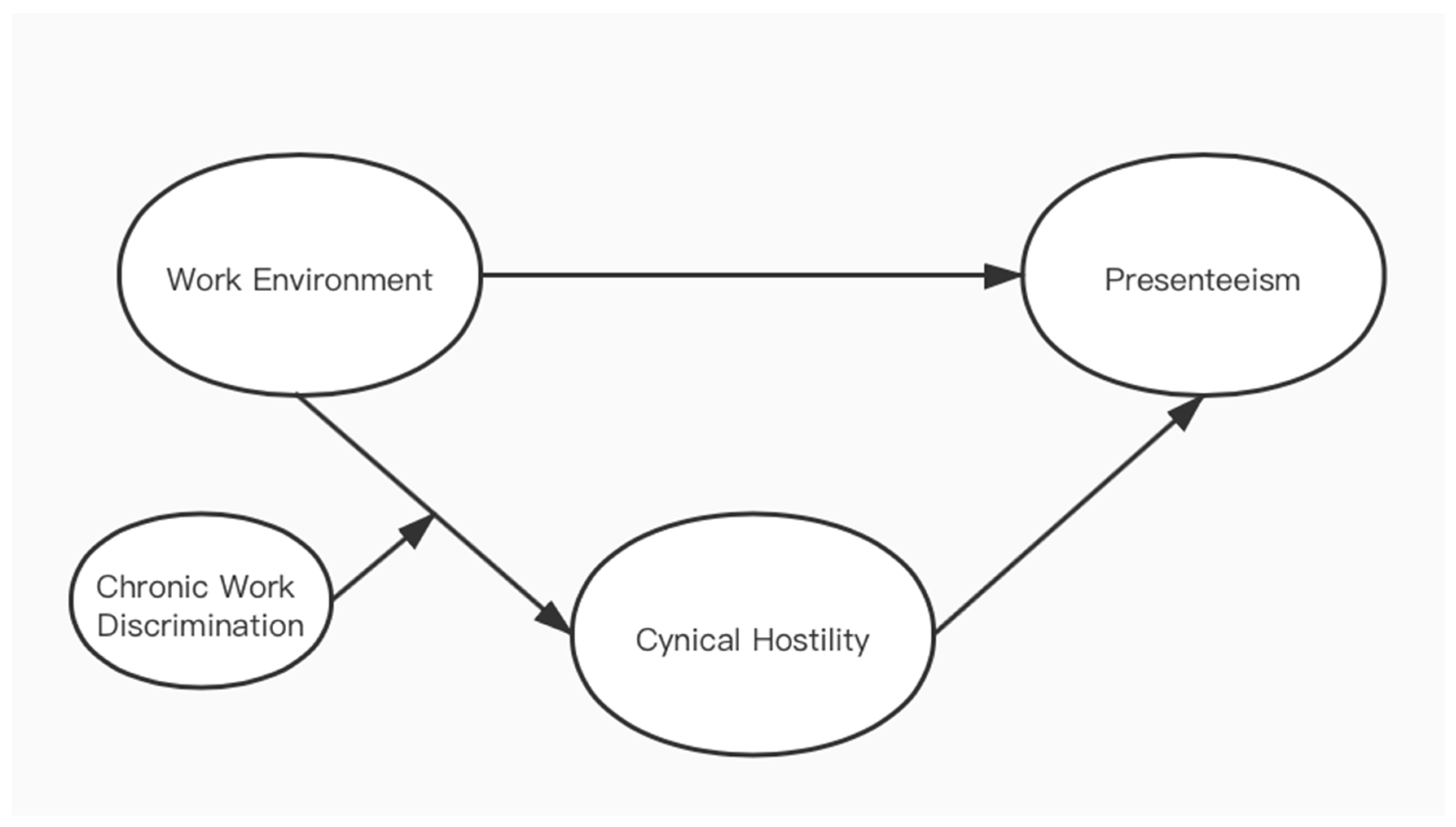

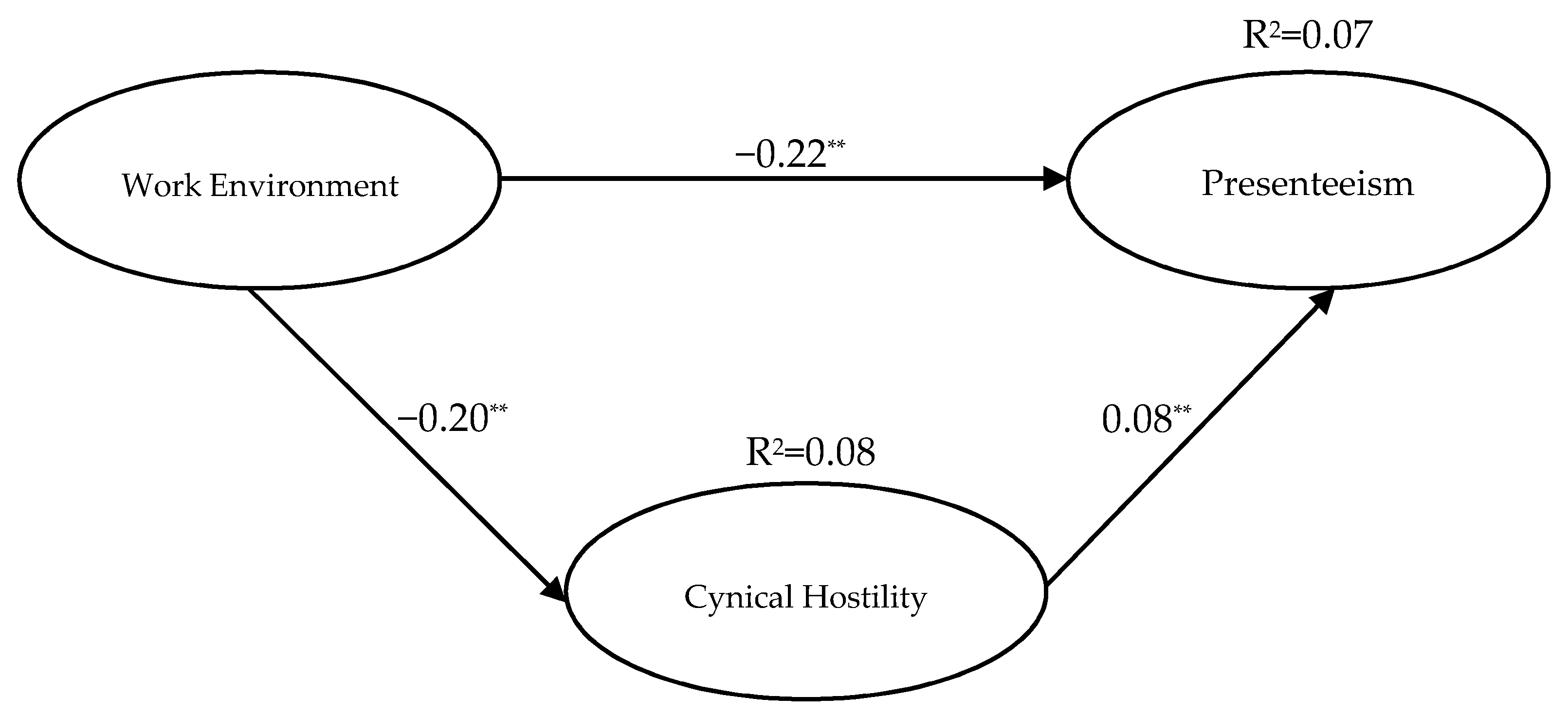

3.2. SEM Model

3.3. Moderated Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costa, P.T.; Zonderman, A.B.; Mccrae, R.R.; Williams, R.B. Cynicism and paranoid alienation in the Cook and Medley HO scale. Psychosom. Med. 1986, 48, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubzansky, L.D.; Sparrow, D.; Jackson, B.; Cohen, S.; Weiss, S.T.; Wright, R.J. Angry breathing: A prospective study of hostility and lung function in the Normative Aging Study. Thorax 2006, 61, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brydon, L.; Lin, J.; Butcher, L.; Hamer, M.; Erusalimsky, J.D.; Blackburn, E.H.; Steptoe, A. Hostility and cellular aging in men from the Whitehall II cohort. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 71, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.W. Hostility and health: Current status of a psychosomatic hypothesis. Health Psychol. 1992, 11, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothe, K.; Bodenlos, J.S.; Whitehead, D.; Olivier, J.; Brantley, P.J. The Psychosocial Vulnerability Model of Hostility as a Predictor of Coronary Heart Disease in Low-income African Americans. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2008, 15, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, K.E.; Differences, I. Cynical hostility and deficiencies in functional support: The moderating role of gender in psychosocial vulnerability to disease. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1999, 27, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.Q.; Smith, T.W.; Turner, C.W.; Guijarro, M.L.; Hallet, A.J. Meta-analytic review of research on hostility and physical health. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.W.; Ruiz, J.M.; Psychology, C. Psychosocial influences on the development and course of coronary heart disease: Current status and implications for research and practice. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 548–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Liang, Q.; Du, X.; Potenza, M.N. Cue-elicited craving–related lentiform activation during gaming deprivation is associated with the emergence of Internet gaming disorder. Addict. Biol. 2020, 25, e12713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Scott, B.A.; Ilies, R. Hostility, job attitudes, and workplace deviance: Test of a multilevel model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenglass, E.R.; Julkunen, J.J.P.; Differences, I. Construct validity and sex differences in Cook-Medley hostility. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1989, 10, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Progovac, A.M.; Chang, Y.F.; Chang, C.H.; Matthews, K.A.; Donohue, J.M.; Scheier, M.F.; Habermann, E.B.; Kuller, L.H.; Goveas, J.S.; Chapman, B.P.J. Are optimism and cynical hostility associated with smoking cessation in older women? Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K. Aggravating conditions: Cynical hostility and neighborhood ambient stressors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2258–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Magnavita, N. Workplace violence and occupational stress in healthcare workers: A chicken-and-egg situation-results of a 6-year follow-up study. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2014, 46, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mental Health at Work: Developing the Business Case. Available online: https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/mental-health-work-developing-business-case (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Hemp, P. Presenteeism: At work—But out of it. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Merrill, R.M.; Aldana, S.G.; Pope, J.E.; Anderson, D.R.; Coberley, C.R.; Whitmer, R.W.; Subcomm, H.R.S. Presenteeism according to healthy behaviors, physical health, and work environment. Popul. Health Manag. 2012, 15, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.D.; Andersen, J.H. Going ill to work–What personal circumstances, attitudes and work-related factors are associated with sickness presenteeism? Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromberg, C.; Aboagye, E.; Hagberg, J.; Bergstrom, G.; Lohela-Karlsson, M. Estimating the effect and economic impact of absenteeism, presenteeism, and work environment-related problems on reductions in productivity from a managerial perspective. Value Health 2017, 20, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.A.; Zhu, M.J.; Xie, X.Y. The determinants of presenteeism: A comprehensive investigation of stress-related factors at work, health, and individual factors among the aging workforce. J. Occup. Health 2016, 58, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, A.; Iverson, D.; Caputi, P.; Magee, C.; Ashbury, F. Relationships between work environment factors and presenteeism mediated by employees’ health: A preliminary study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 56, 1319–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, L.C.; Smith, T.W. Patterns of hostility and social support: Conceptualizing psychosocial risk factors as characteristics of the person and the environment. J. Res. Personal. 1999, 33, 281–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesler, D.J. Contemporary interpersonal theory and research: Personality, psychopathology, and psychotherapy. Wiley series in clinical psychology and personality. J. Psychother. Pract. Res. 1996, 6, 339. [Google Scholar]

- Hakulinen, C.; Jokela, M.; Hintsanen, M.; Pulkkiraback, L.; Hintsa, T.; Merjonen, P.; Josefsson, K.; Kahonen, M.; Raitakari, O.T.; Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. Childhood family factors predict developmental trajectories of hostility and anger: A prospective study from childhood into middle adulthood. Psychol. Med. 2013, 43, 2417–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darity, W.A., Jr. Employment discrimination, segregation, and health. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poscia, A.; Moscato, U.; La Milia, D.I.; Milovanovic, S.; Stojanovic, J.; Borghini, A.; Collamati, A.; Ricciardi, W.; Magnavita, N. Workplace health promotion for older workers: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2019 Hiscox Ageism in the Workplace StudyTM. Available online: https://www.hiscox.com/documents/2019-Hiscox-Ageism-Workplace-Study.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Bhui, K.; Stansfeld, S.; Mckenzie, K.; Karlsen, S.; Nazroo, J.; Weich, S. Racial/ethnic discrimination and common mental disorders among workers: Findings from the EMPIRIC study of ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom? Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.T.; Branscombe, N.R.; Postmes, T.; Garcia, A. The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 921–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, J.N.; Emery, C.F. Psychosocial vulnerability, hostility, and family history of coronary heart disease among male and female college students. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2002, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, K.E.; Hope, C.W. Cynical hostility and the psychosocial vulnerability model of disease risk: Confounding effects of neuroticism (negative affectivity) bias. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J.; Koskenvuo, M.; Uutela, A.; Pentti, J. Response of hostile individuals to stressful change in their working lives: Test of a psychosocial vulnerability model. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barefoot, J.C.; Beckham, J.C.; Haney, T.L.; Siegler, I.C.; Lipkus, I.M. Age differences in hostility among middle-aged and older adults. Psychol. Aging 1993, 8, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Highlights.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Sustainable Development Goal 8. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg8 (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Vanni, K.J.; Virtanen, P.; Luukkaala, T.; Nygard, C.H. Relationship between perceived work ability and productivity loss. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2012, 18, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilmarinen, J.; Rantanen, J. Promotion of work ability during ageing. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1999, 36, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.W.; Medley, D.M. Proposed hostility and pharisaic-virtue scales for the MMPI. J. Appl. Psychol. 1954, 38, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Yu, Y.; Jackson, J.S.; Anderson, N.B. Racial differences in physical and mental health. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.H. Introduction to the special section: Structural equation modeling in clinical research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1994, 62, 427–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccallum, R.C.; Austin, J.T. Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2000, 51, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Shi, H.; Guo, Y.; Jin, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Deng, J. Effect of work environment on presenteeism among aging american workers: The moderated mediating effect of sense of control. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovniak, L.S.; Anderson, E.S.; Winett, R.A.; Medicine, R. Social cognitive determinants of physical activity in young adults: A prospective structural equation analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Guo, Y.; Shi, H.; Gao, Y.; Yang, T. Effect of discrimination on presenteeism among aging workers in the United States: Moderated mediation effect of positive and negative affect. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, G.W.; Lau, R.S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 296–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everson-Rose, S.A.; Skarupski, K.A.; Barnes, L.L.; Beck, T.; Evans, D.A.; de Leon, C.F.M. Neighborhood socioeconomic conditions are associated with psychosocial functioning in older black and white adults. Health Place 2011, 17, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angerer, P.; Siebert, U.; Kothny, W.; Muhlbauer, D.; Mudra, H.; Von Schacky, C. Impact of social support, cynical hostility and anger expression on progression of coronary atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 36, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, U.; Lund, R.; Damsgaard, M.T.; Holstein, B.E.; Ditlevsen, S.; Diderichsen, F.; Due, P.; Iversen, L.; Lynch, J. Cynical hostility, socioeconomic position, health behaviors, and symptom load: A cross-sectional analysis in a Danish population-based study. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloydjones, D.; Adams, R.J.; Brown, T.M.; Carnethon, M.; Dai, S.; De, S.G.; Ferguson, T.B.; Ford, E.; Furie, K.; Gillespie, C. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 127, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Izawa, S.; Eto, Y.; Yamada, K.C.; Nakano, M.; Yamada, H.; Nagayama, M.; Kikuchi, T.; Nomura, S. Cynical hostility, anger expression style, and acute myocardial infarction in middle-aged Japanese men. Behav. Med. 2011, 37, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindle, H.A.; Chang, Y.F.; Kuller, L.H.; Manson, J.E.; Robinson, J.G.; Rosal, M.C.; Siegle, G.J.; Matthews, K.A. Optimism, cynical hostility, and incident coronary heart disease and mortality in the women’s health initiative. Circulation 2009, 120, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornroos, M.; Elovainio, M.; Keltikangasjarvinen, L.; Hintsa, T.; Pulkkiraback, L.; Hakulinen, C.; Merjonen, P.; Theorell, T.; Kivimaki, M.; Raitakari, O.T.; et al. Is there a two-way relationship between cynicism and job strain? Evidence from a prospective population-based study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 57, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Wright, C.E.; Kunzebrecht, S.R.; Iliffe, S. Dispositional optimism and health behaviour in community-dwelling older people: Associations with healthy ageing. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantono, B.; Moskowitz, D.S.; Nigam, A. The metabolic costs of hostility in healthy adult men and women: Cross-sectional and prospective analyses. J. Psychosom. Res. 2013, 75, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- News, C. World Journal: “the Silver Generation” is Becoming an Important Part of the American Labor Market. Available online: http://www.chinanews.com/hr/2019/02-20/8759386.shtml (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Brondolo, E.; Hausmann, L.R.M.; Jhalani, J.; Pencille, M.; Atencio-Bacayon, J.; Kumar, A.; Kwok, J.; Ullah, J.; Roth, A.; Chen, D.; et al. Dimensions of perceived racism and self-reported health: Examination of racial/ethnic differences and potential mediators. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011, 42, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lei, R.; Yang, T. Public service motivation as a mediator of the relationship between job stress and presenteeism: A cross-sectional study from Chinese public hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Items | Number of Cases | Mean | SD | Missing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | |||||

| Cynical Hostility | 1. Most people dislike putting themselves out to help other people. | 2841 | 3.32 | 1.466 | 85 | 2.9 |

| 2. Most people will use somewhat unfair means to gain profit or an advantage rather than lose it. | 2828 | 3.45 | 1.506 | 98 | 3.3 | |

| 3. No one cares much what happens to you. | 2842 | 2.09 | 1.430 | 84 | 2.9 | |

| 4. I think most people would lie in order to get ahead. | 2900 | 3.42 | 1.512 | 26 | 0.9 | |

| 5. I commonly wonder what hidden reasons another person may have for doing something nice for me. | 2883 | 2.54 | 1.482 | 43 | 1.5 | |

| Perceived Ability to Work | 1. How many points would you give your current ability to work? | 2864 | 8.63 | 1.492 | 62 | 2.1 |

| 2. Thinking about the physical demands of your job, how do you rate your current ability to meet those demands? | 2876 | 8.72 | 1.536 | 50 | 1.7 | |

| 3. Thinking about the mental demands of your job, how do you rate your current ability to meet those demands? | 2879 | 8.89 | 1.314 | 47 | 1.6 | |

| 4. Thinking about the interpersonal demands of your job, how do you rate your current ability to meet those demands? | 2859 | 8.73 | 1.420 | 67 | 2.3 | |

| Chronic Work Discrimination | 1. How often are you UNFAIRLY given tasks at work that no one else wants to do? | 2881 | 2.12 | 1.475 | 45 | 1.5 |

| 2. How often are you watched more closely than others? | 2873 | 1.72 | 1.321 | 53 | 1.8 | |

| 3. How often are you bothered by your supervisor or coworkers making slurs or jokes about women or racial or ethnic groups? | 2870 | 1.39 | .956 | 56 | 1.9 | |

| 4. How often do you feel that you have to work twice as hard as others at work? | 2871 | 2.10 | 1.653 | 55 | 1.9 | |

| 5. How often do you feel that you are ignored or not taken seriously by your boss? | 2870 | 1.78 | 1.351 | 56 | 1.9 | |

| 6. How often have you been unfairly humiliated in front of others at work? | 2875 | 1.30 | 0.772 | 51 | 1.7 | |

| Work Environment | 1. I have too much work to do everything well. | 2876 | 2.07 | 0.960 | 50 | 1.7 |

| 2. I have a lot to say about what happens in my job. | 2868 | 2.94 | 1.000 | 58 | 2.0 | |

| 3. Promotions are handled fairly. | 2855 | 3.33 | 1.225 | 71 | 2.5 | |

| 4. I have the training opportunities I need to perform my job safely and competently. | 2862 | 3.40 | 0.839 | 64 | 2.2 | |

| 5. The people I work with can be relied on when I need help. | 2866 | 3.30 | 0.793 | 60 | 2.1 | |

| Model Description | Chi2 | df | RMSEA (90% CI) | GIF | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thresholds for acceptable fit | < 0.06 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ||

| Baseline model V1 | 911.069 | 74 | 0.062 (0.059, 0.066) | 0.955 | 0.939 | 0.926 |

| Model V2 excludes low indicator reliability (<0.3) | 448.320 | 60 | 0.047 (0.043, 0.051) | 0.976 | 0.971 | 0.963 |

| Variable | BC 5000 BOOT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Work Discrimination | Cynical Hostility | ||||

| IND | SE | LL95 | UL95 | ||

| Low | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.0769 | −0.0239 |

| Mean | 1.74 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.0585 | −0.0186 |

| High | 2.65 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.0473 | −0.0105 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, J.; Wu, Z.; Yang, T.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Z. Effect of Work Environment on Presenteeism among Aging American Workers: The Moderated Mediating Effect of Cynical Hostility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135314

Deng J, Wu Z, Yang T, Cao Y, Chen Z. Effect of Work Environment on Presenteeism among Aging American Workers: The Moderated Mediating Effect of Cynical Hostility. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135314

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Jianwei, Zhennan Wu, Tianan Yang, Yunfei Cao, and Zhenjiao Chen. 2020. "Effect of Work Environment on Presenteeism among Aging American Workers: The Moderated Mediating Effect of Cynical Hostility" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135314

APA StyleDeng, J., Wu, Z., Yang, T., Cao, Y., & Chen, Z. (2020). Effect of Work Environment on Presenteeism among Aging American Workers: The Moderated Mediating Effect of Cynical Hostility. Sustainability, 12(13), 5314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135314