Abstract

The study aims to understand and explore situations of collaboration between various actors in connection with a university-driven innovation intermediary organisation, and how the intermediary organisation facilitates collaboration in the making. To this end, we employ a case of a university-driven long-lasting intermediary organisation within the agricultural and forestry sectors. We examine three collaborative situations, using practice-based research and process theories as theoretical perspectives. A narrative approach is adopted as the method of investigation. The findings are presented in a conceptual model where the structures of the intermediary organisation are translated into practices, against which individuals can develop their collaboration processes. It is concluded that collaboration in the making is formed in the interplay between structures, practices and processes in relations between people. This implies that the organising of collaboration should focus its attention not only on structures but also on the practices and processes formed between people. The study contributes to the understanding of the organising of university innovation intermediary organisations by untangling the relations between structures, practices and processes in situations of collaboration between people.

1. Introduction

The study aims to understand and explore collaborative situations involving various actors in connection with a university-driven innovation intermediary organisation and how the intermediary organisation facilitates collaboration in the making.

1.1. Univeristy Innovation Intermediary Organisations

In the current era of climate change and pressing global sustainability challenges, university collaboration with industry and societal actors could significantly contribute to the necessary transition to a more sustainable society [1]. Collaboration between universities and industry has increased dramatically in recent decades [2,3], along with an increase in the number of various intermediary organisations [4,5]. New and better ways to collaborate and share knowledge, as well as best practices, are crucial for keeping agriculture and food production competitive, ecologically viable and socially equitable [6,7].

University–industry collaboration has been conceptualised as a higher-level process that encompasses cooperation, teamwork and coordination [8,9]. The literature on university–industry collaboration has largely focused on how interaction is carried out by identifying categories of links or on who interacts and why, cf. [10]. Actors from different domains are motivated to enter into collaboration by, for example, new knowledge, inspiration, new methods and the expectation of or need for innovative solutions [11]. Traditionally, collaboration between universities and industry has been discussed in terms of partnerships, where the business practitioner initiates the collaboration with a researcher by proposing a research problem that requires an innovative solution and new knowledge [9]. The literature addressing these types of collaborations often focuses on dyadic partnership, grounded in a problem to be solved and generally terminated when the problem is solved [12].

However, in the last decade, collaboration has started to emerge in other forms as different types of university–industry intermediaries have been investigated (e.g., [13]) as well as the role of intermediaries as facilitators [14]. Such examples are arenas or platforms for collaboration, often initiated by the university, and with numerous members (such as the case study of this paper). Such arenas or platforms are initiated based on an assumed reciprocal commitment, rather than concrete projects. The aim of the arena is often formulated by the initiator, i.e., the university, and the members commit themselves to hoped-for potential value or a hoped-for potential concrete partnership.

The focus of this paper is collaboration within a university-driven innovation intermediary organisation in the agricultural and forestry sectors. An innovation intermediary is defined as “an organisation or body that acts as agent or broker in any aspect of the innovation process between two or more parties” [4] (p. 721). An increasing body of literature, not least in agricultural research, is raising the importance of innovation intermediary organisations as important drivers for innovation and change towards more sustainable socio-technical systems [4,5,15]. Innovation intermediaries are assumed to perform a relatively large variety of activities; for example, information and knowledge processing and combination/recombination, gatekeeping and brokering, commercialisation, evaluation and outcome monitoring [4,5]. In agriculture, the main functions are demand articulation, network brokerage and innovation process management [15].

This implies that innovation intermediaries are seen not only as mere facilitators of innovation but also as a source and carrier of innovation [15,16]. Recently, a multi-faceted view of the interaction of innovation intermediaries in collaborative projects has been suggested: “more complex, enriched and involved roles as they/…/engage in co-creative innovative activity with collaborators, in a process of wider co-creation and co-development” [17] (p. 70). This brings the attention to the micro-level of collaboration, which is less well investigated and understood [2,9,16,18]. Hence, the analysis must be performed in specific situations, times and contexts. This enables actions and interactions between individuals to be studied, as well as the implications for the shaping of intermediary organisations.

1.2. The Micro-Level of Collaboration

The interest in the micro-level perspective has also recently been highlighted in the literature streams of university knowledge transfer and exchange [2,18,19]. Nevertheless, the understanding of the micro-level processes of collaboration between universities and other actors is still in its infancy [2]. The research on university collaborations frequently takes a macro-structure perspective, such as through the triple and quadruple helix models [19]. However, these models and system-level perspectives fail to address the social processes in the making [18,20], i.e., the “processes of forming, developing and coordinating UI [university–industry] collaboration” [10] (p. 159). Collaboration studies that take a system perspective have the system as the primary concern, and micro-processes between humans become secondary [21]. Within the structural perspectives, people are assumed to be rational and goal-seeking beings [22]. According to Patriotta [23], the structure is often seen as an effect of rational individuals, and it is added that “This ‘alienation’ of theory from practice underscores the need to engage with the study of processes, streams, flows, and flux” [23] (p. 9).

If we instead see collaboration as knowledge creation processes, it includes the ability to interpret and make sense of conversations and interactions with others, at a specific time and in a specific context. This process of working together at the micro-level is recognised to be rather poorly understood, i.e., [24]. With the help of narratives, the analysis can be taken down to specific situations, times and contexts—actors and interactions between individuals—that at the same time lets us understand the relation to the structure of the intermediary organisation.

In this study, we argue that to understand and explain the collaboration between actors, the analysis needs to take its starting point as what happens in specific situations. A practice-based approach enables the exploration of the building blocks of the collaboration process, such as actions, situations and relationships [25]. By adopting a practice-based and process approach in exploring the challenges of collaboration between academia and industry, attention is re-directed from structure and the systemic settings to the concrete activities of collaboration, what people do and the practices they perform. Furthermore, it sees the individual action as always embedded within a network of social practices [26] and processes in relations between people [21]. However, there are a limited number of scientific contributions with a practice-based perspective of collaboration [20].

1.3. Aim of this Study

Hence, this study aims to understand and explore situations of collaboration between various actors in connection with a university-driven innovation intermediary organisation, and how the intermediary organisation facilitates collaboration in the making. We do this by taking the actions of people in specific situations as the starting point for the analysis. More concretely, we address the two following research questions:

- (1)

- How can we understand and explore collaboration in the making within the intermediary organization?

- (2)

- How does the intermediary organisation facilitate collaboration in the making?

The empirical backdrop of the study is a university-driven innovation intermediary organisation within the agricultural and forestry sectors. Started in 2004, the intermediary organisation currently has around 90 partner organisations, ranging from small firms and producer organisations with numerous members to large businesses, along with local, regional and national authorities. We examine three collaborative situations, and a narrative approach is adopted as the method of investigation. The intermediary organisation involves both industry and societal stakeholders and focuses on creating meeting places [27], and seed-funding new collaborative research and development (R&D) initiatives and student projects.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: the next section outlines the theoretical background to practice-based approach and process theories, the methodology is detailed in Section 3, narratives are presented in Section 4, and Section 5 contains analysis and discussion, followed by conclusions in Section 6.

2. Frame of Reference

This section outlines the frame of reference of this study—practice-based approaches and process theories. These two perspectives are not entirely separate but melt into each other with a focus on what happens in practice [28]. However, below, they are presented separately for clarity. In both perspectives, the questions are how, what and why do things happen.

2.1. Practice-Based Approach

In order to understand collaborative situations in intermediary organisations, we start from the practice-oriented turn within organisational and collaboration research [29], the core of which consists of participants’ practice and what is actually done [30]. For the purpose of this study, we focus on the relationship between structure and practice mutually created. In this way, we keep a focus both on what people do and the social and formal structures where collaboration takes place.

In the previous century, works by writers such as Heidegger, Wittgenstein and even Aristotle were influential in forming the background to practice-based research [31]. Representatives of practice theories [32] emphasise that there is no single uniform practice theory but rather a practice turn in social and organisational studies. The core of the plurality of practice theories is that it puts recurrent activities, interactions and practices in focus and uses this as the unit of analysis. Practice-based research takes a starting point where seemingly mundane activities play the lead role [33]. Practice-based researchers see the world as a seamless assemblage of practices in continuous relation to each other. The queries of what, how and why are the theoretical questions that permeate practice theories [31].

Practice-based research states that social structures only exist as long as practices are performed that keep them in place. This highlights the two-way relationship between practices and structures, and the fact that social structures are temporal and can be torn down or changed if they are no longer supported by practices. As the aspects of power, politics and conflict are always present, practices are constantly open to contestation, and this keeps them continuously in a state of tension and flux [31,32]. Organisations, as formal structures, are part of this perspective. Organisations are governed by formal structures that organise what people are doing [34]. Therefore, one way to approach collaboration is through maps of structures. This perspective can be applied to the intermediary organisation focused on by this study.

Practice is described as routinised activities and postures, as in the roles we play in certain contexts, e.g., the teacher–student relationship. Thus, the human is a carrier and performer of social practices. However, in doing so, there is normally space for initiative, creativity, individual performance and adaption [31]. This is where new processes and collaborations between people can start.

However, as Chia and Holt [22] note, a challenge in practice-based research is avoiding ending up with mere descriptions of organisational practices but rather, following Schatzki et al. [32], seeing knowledge and meaning residing in a nexus of practices. The affordance of a practice-based approach is not only that it describes the world in terms of what is being done and redone but that these practices shape the meaning given to activities and contribute to the formation of the identity of the people involved [22,35]. Nicolini [31] (p. 7) notes that “Practices are, in fact, meaning-making, identity forming, and order-producing activities.”.

2.2. Process Theories

In our view, collaboration in the making has a focus on what is done, how and why. The practice-based approach addresses collaboration as a system that limits the individual but acknowledges that the system can be formed and re-formed by the individuals [32]. Process theories, on the other hand, focus on the interplay between individuals and formal and social structures. Process theories understand the world as “…in flux, in perpetual motion, as continually in the process of becoming.” [36] (p. 1). Order is emergent, hence spontaneous, without intention or control, but through individuals interacting with each other [21].

While a practice-based approach has the individual action, situation, material conditions and, in some way, systems as a starting point, it does not take adequate account of processes. Therefore, we combine the practice-based approach with process theories [36,37]. Supplementing the concept of practice with the concept of process allows for “structures” to take various shapes, ranging from firmer to looser. Hence, it allows for the better interpretation and understanding of contexts that are differently structured and organized. Thus, we shift the focus towards actions and relations between people within the frame of various structures. Consequently, we reduce and move beyond the criticism of Stacey and Mowles [21], that Nicolini [31] has an overly dominant view of structures, systems and individuals. Practice-based research, together with process theories, offers a tool that helps us focus on collaboration in the making. The processes of interaction between people can be generalised, but the results of these processes are unique and cannot be predicted beforehand [21].

When applying structural and cognitive perspectives, there is an adherent risk that people are assumed to be rational and goal-seeking beings [22]. The structure is often seen as an effect of rational individuals, and this view contributes to an alienation of theory from practice [23]. This underscores the need to focus on processes and what is happening [23].

Starting the process turn in organisational studies, Weick [38] argues that social scientists should focus on actions and processes instead of entities like organisations, roles and hierarchies. Thus, we should use verbs more frequently instead of nouns, such as in “organising” rather than “organisation”. Weick [38] even argues that we should “stamp out the nouns” (p. 44) and replace them with verbs. He describes process as the interaction between actions and meaning-making, and refers to this as sense-making [39]. He continues: “The language of sensemaking captures the realities of agency, flow, equivocality, transience, reaccomplishment, unfolding, and emergence, realities that are often obscured by the language of variables, nouns, quantities, and structures” [40] (p. 410).

In this study, we take the issue of nouns and verbs one step further and see the need to deal with both at the same time. As noun-making is necessary for human sense-making, we are incapable of thinking purely in terms of processes [41]. Hence, noun-making is an indispensable ingredient for coming to grips with processes [41]. Czarniawska [42] sees the current focus on nouns in models of organisational change as a reminder of the influence of natural sciences on social science. She argues that social sciences missed the point of the models in natural sciences; it is not only about filling the boxes of the models with nouns but also about finding the verbs to make the model meaningful.

In summary, processes of collaboration can be seen as a continuous motion between interacting people and structures. In a collaboration situation, there is a dialectic reciprocal relationship between structures on the one hand, and practices and processes on the other. It includes knowledge creation processes in relations between people, in a specific context and time period.

3. Case and Method

This section presents the case study of an intermediary organisation and outlines the methods in which a narrative approach is adopted to understand and explain collaboration between various actors.

3.1. Case

The studied case is an intermediary organisation, SLU Partnership Alnarp, started in 2004 as a collaborative platform at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Today, the intermediary organisation has around 90 partner organisations, ranging from small firms and producer organisations with numerous members to large businesses and local, regional and national authorities. The intermediary organisation consists of a board, a working committee with an operating manager, and six subject groups [43]. The activities are R&D projects, funded together by both university and partner organisations; meeting places such as seminars, workshops and field excursions; and student projects and a mentorship program, along with regular meetings of the board, working committee and subject groups. Researchers at the university can apply for R&D funding from the intermediary organisation, provided that the applications include 50% funding from partner organisations. The applications are first discussed in the relevant subject group and then decided upon by the board. The working committee, which meets every month, decides on funding for meeting places and student projects [43].

Thus, the model of the intermediary organisation facilitates the meeting between the university, authorities, industry and civil society to discuss current issues, and offers tools for starting to deal with them. The intermediary organization involves both industry and societal stakeholders and focuses on creating meeting places [27] and seed-funding new collaborative R&D initiatives and student projects. It views everyone’s knowledge as legitimate, allows for multiple value propositions, and stimulates the co-creation of new ways forward [27].

As this is a single case study, our aim is not to generalize but rather to explore certain aspects that can enrich our understanding of this specific phenomenon.

3.2. Method

This is a qualitative single case study. The first author of this article was the operating manager of the intermediary organisation from 2013 to 2018, while the two other authors evaluated the organisation in 2018–2019. Thus, we used a dialogue between the “insider” (first author) and “outsiders” (second and third authors) to understand processes in an organisation [44]. The two outsiders gained empirical understanding through the evaluation. The analysis begins in a thick description of the intermediary organisation as detailed interpretations of collaboration in the making. Nicolini [45] argues for a combination of zooming in on and zooming out from the immediate operation and the empirical material. In summary, the method used in this study can be described as a dialogue between practice and theory, between an insider and outsiders, and zooming in and zooming out. The interpretive dialogue has the advantage of providing insights into more in-depth details of the backstage, experience-oriented knowledge that goes beyond interviews [46]. The discussions between the three authors through critical questions resulted in new insights, challenging the theoretical and methodological framework.

As the aim of this study was to understand and explore situations of collaboration between various actors, the question we posed to our empirical material was “how can we interpret and understand collaboration processes in the empirical material, viewed through the theoretical lenses of practice-based approach and process theories?”. According to Kärreman and Alvesson [47] (p. 59), “… some situations in organisations may be seen as the organisation ‘written small’ and the close and detailed interpretation of these may, if combined with sufficient background and context knowledge, open up a window for a broader understanding of organisations.” Hence, we adopted a narrative approach and identified three narratives to illustrate the empirical material.

A narrative approach is in line with practice-based and process research, where the focus is also on aspects like heterogeneity and unpredictable events that may shine forth [48,49]. Narratives provide the opportunity to describe some aspects of life as it is [50]. The narrative approach also connects to process theories where processes can be generalized, while the results are seen as local and specific [21].

Since we cannot recount the results of numerous long narratives, we use small narratives, what Boje [51] calls ante-narratives or micro-stories. Such stories “are told without the proper plot sequence and mediated coherence preferred in narrative theory” [51] (p. 3). Boje further writes “the micro-stories want to think, feel and see the world the way it was seen in that time and place” and “to see the world through the eyes and mind-set of the Other” [51] (p. 48).

Being aware of the bias risk, we used several observations to support any claims and tried to use different interpretative lenses throughout the study [52]. We recognise the role of the researcher as shaped by previous experiences, by the social and cultural environment to which he or she belongs, not only theoretical points of view [52]. Thus, we acknowledge the risk of different interpretations depending on individual experiences and backgrounds. Therefore, we were careful in interviews to constantly ask questions like “What do/did you think? Can you develop? Are there other similar situations?”.

In short, we present three narratives, like interviews, to represent the extensive empirical material. It should be noted that while it has not been possible to explore all the practices of the intermediary organisation, the narratives should be regarded as illustrative cases for the analysis of collaboration in the making.

4. The Case Study

This section contains three collaborative situations in the form of narratives. These narratives are examples illustrating the empirical material.

4.1. Narrative (1): A Board Meeting—Strategy Discussion

The board of the intermediary organisation consists of the chairpersons of the subject groups, coming from non-university actors, and the two deans of the two faculties involved [43]. The board makes decisions on grants for R&D projects and handles strategic issues for the intermediary organisation. The board mostly consists of long-term members, which ensures continuity and stability.

A part of the board meeting is spent on the board members’ reports from their perspective and sense of what is going on in their wider context that could be of relevance to the operations of the intermediary organisation. Examples of the issues discussed were trends in the industry and sectors, the financing of applied research, concerns of keeping and building applied research competence, policies affecting the industries and the university, education, and the need for skilled labour at every level of the industry. Christine (we use fictive names throughout the paper) is one of the board members, and Lars is one of the deans.

Christine: “Right from the start, I was very impressed with the competencies that existed in the group. They were genuinely interested in the intermediary organisation as a phenomenon. And there was a genuine driving force that this would be something good. Every time, new thoughts and ideas came up on how this could be improved and changed. And everyone did not agree from the start. The atmosphere in the group was that everyone spoke their mind, which made things happen. Perhaps we didn’t follow through on some of the strategic discussions quite like we could have. Then, of course, the project discussions took a pretty big part of the meetings, but that was quite OK; we wanted many applications. On some occasions, different external events put our industries in more or less difficult situations. Then the reasoning in the group was how to handle it and support each other.”.

Lars: “The board meetings have a very important function in getting perspectives from different parts of the sectors, what is going on and what is around the corner. Then there is the legitimacy; it confirms the commitment of the involved actors, and that the operations are effective and efficient. The board has a quality assurance function in that we ensure that the granted projects are relevant and of good quality. And most importantly, future issues and development of the intermediary organisation at a strategic level are discussed. How can such a tool keep up, adapt and develop continuously? There is a wide range of important functions to the board.”.

4.2. Narrative (2): A Subject Group Meeting—Aphids in Root Crops

The intermediary organisation has six subject groups, e.g., animal husbandry, horticulture, and agricultural crop production [43]. The partner organisations are members of these groups according to their interests. The subject groups meet twice a year to discuss the current situation within their field of interest and any activities needed. They also read and discuss the applications for R&D funding coming in to the intermediary organisation. When Victoria, working for the root crop industry, attended the meeting of the crop production subject group, she read a project application from university researcher Felipe about aphids in grains and apples.

Victoria: “I read Felipe’s application to the subject group, about new methods against aphids in grains and apples, and thought we should try this in our root crops. One of my co-workers is sometimes at the department, so with his help, a meeting with Felipe was arranged. Felipe presented his research, and I presented what we do in root crops. Together, we worked out a simple field trial plan. It has worked out great; Felipe has the knowledge and methods for academic work. If it had not been for the intermediary organisation, we would have never met.”.

Felipe: “For me, it started when a guy I know from the department said to me, “you should talk to Victoria, I think you could do some interesting things together”. So, we met, and we found each other on the same page, since she works for growers and I like to work with growers as well. The next step was to do a pilot field trial, just a small one, but the results were interesting, and we will be continuing.”.

Further dialogue between the involved organisations followed, where both had an interest in developing these issues further. New plans were made, and additional resources applied for from the intermediary organisation and elsewhere.

4.3. Narrative (3): A Seminar—Soil Carbon Storage by Subsidiary Crops

The intermediary organisation arranges a large number of seminars, workshops and excursions every year. These events are vital meeting places for academia, industry, and society, and they provide opportunities to discuss and deliberate on current topics across organisational borders [43].

There has been an increasing interest in subsidiary crops over the last few years in both agricultural and horticultural crop rotations, for reasons such as nutrient retention, soil conservation and biodiversity. The university has had a few applied research projects about this, some of which were partly financed by the intermediary organisation and its partners. The research projects have been presented at yearly seminars and field excursions, organised by the researchers and the intermediary organisation. At these events, farmers, advisors, the agri-business industry and authorities have presented their views and reflections on subsidiary crops. Niels is one of the researchers working with the projects on subsidiary crops and has met Sophie, who is as an expert advisor at a national authority.

Niels: “The seminars and field excursions are valuable as they open up new perspectives on things you realise you have to keep track of, and perhaps include for the future. You get to hear what kind of questions the farmers have, and the advisors. The authorities for instance, are interested in soil carbon, which is the area of my own research. After making contact at these seminars, I have been invited to meetings about developing tools for evaluating the contribution of subsidiary crops to soil carbon storage. Now we are working on a project funded by the authorities, on the impact of the time of establishment of the subsidiary crop.”.

Sophie: “For those of us who are located here, it is great to be close to the university, as there are Niels and his colleagues, so we can benefit from each other. I have met Niels at various workshops and seminars. My contacts with Niels and his colleagues are certainly part of a general knowledge build-up on subsidiary crops for, for example, biogas, reducing nitrogen loss, and soil carbon storage. Our collaboration might not be super organised, but it feels like we benefit from each other.”.

5. Analysis and Discussion

This study aims to understand and explore situations of collaboration between various actors in connection with a university-driven innovation intermediary organisation, and how the intermediary organisation facilitates collaboration in the making. With the help of the narratives above, the analysis is taken down to specific situations of interactions between individuals in time and context, that at the same time lets us understand the relation to the structure of the intermediary organisation. It is shown how the actors in the three narratives use structures for their sensemaking, identity-forming and order-producing, in a reciprocal dance between structure, practices and processes.

5.1. Structures

To start, the intermediary organisation can be described as different structures. The structures constitute a map [34], a sort of context in which to understand the collaboration in the three narratives. The three narratives each represent different structures of the intermediary organisation, from a board meeting with a fixed structure, to a seminar with a loose structure (see Section 3.1). Therefore, the structures within the intermediary organisation can be depicted along a continuum from fixed to fluid.

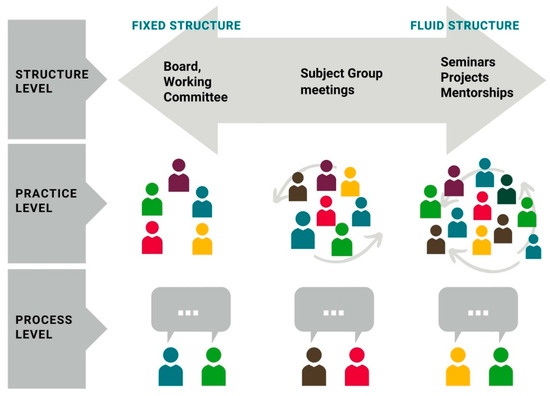

Furthermore, the narratives illustrate how the structures of the intermediary organisation constitute arenas for practices, where people meet and engage in a board meeting, subject group meeting or a seminar. These practices, in turn, present possibilities for processes to take place in relations between people. Thus, the different structures of the intermediary organisation give shape to varying practices, which in turn allow for multiple ways of action and performance by people. An attempt to graphically illustrate the dynamics between the varying structures, practices and processes is made in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Model of structures, practices and processes of the university intermediary organisation. The structures range on a continuum from fixed to more fluid structures. The top left side of the figure shows the fixed structures, i.e., procedures of the board and working committee. The top right side of the figure shows fluid structures, such as seminars and projects, where informal elements, unexpected meetings and conversations, can be more apparent. The different structures enable various kinds of practices for people to engage in, which in turn allows for processes between people. The arrows in the practice level indicate that the participants and group size can vary. On the process level, only two persons are depicted for graphical reasons; there can naturally be multiple relations and persons.

The top left side of Figure 1 are shown the fixed structures of the procedures of the board and working committee. While the fixed structures contribute to the frame of the meetings, they do not determine the content. A firm structure implies a tighter interpretational frame, influencing the practices and processes that are formed between people. The board, which consists of mainly long-term members, makes formal decisions on the funding of R&D projects in a tradition since 2004, ensuring continuity and stability. These meetings have a similar agenda each time, and participants know, fairly well, what to expect of it and what is expected of them. This allows for continuity but, most importantly, makes commitment and action possible. Primarily, the commitment is made to the structure and not necessarily to the participants in the meeting. However, with time [37], trust and commitment between the participants start to grow, as in the narrative in Section 4.1.

The top right side of Figure 1 shows the fluid structures, such as seminars, workshops, excursions, R&D projects and student projects and a mentorship programme. Meeting places, such as seminars, can be organised flexibly by decisions in the monthly working committee and thus respond to upcoming needs of, for example, industry or academia. A looser structure implies a more flexible interpretational frame, which allows for a larger span of spontaneity, creativity and unexpected acts in the processes between people, which can alter the practice and the structure at hand, in sometimes-unpredictable ways [39]. The participants in these activities can vary between different occasions.

The subject group meetings take an intermediary position along the fixed–fluid continuum in Figure 1, as they have both fixed and fluid items on the agenda, e.g., reviewing applications and discussing current trends and needs for activities. The participants are mostly well known to each other, but occasionally, new partners join the group.

These different structures within the intermediary organisation contribute to a creative tension between the orderly structures and the spontaneous, looser structures [53]. When this is aligned with individual intentions, motives and relational processes that make sense of collaboration, actors use the different structures and practices to set their collaboration processes in motion. The three narratives illustrate how actors use the structures and practices to develop their collaborations; for example, from ideas that start in seminars (looser structures), they can apply for funding from the board (firm structure), enabling projects to start. The project results can be presented and discussed in a field excursion (looser structure), arranged by the project co-workers and the working committee (firm structure).

5.2. Practices

The scientific literature stream of university knowledge transfer and exchange research often takes a static macro perspective [19] or a helicopter view [54] of collaboration. Hence, the focus is on the structures and the elements of the system. When adopting a practice perspective, the focus shifts to recurrent activities.

Practices are described as routinised activities and postures, as in the roles we play in certain contexts. As the intermediary organisation facilitates meetings between different actors from the university, industry, authorities and civil society, it contributes to the creation of a common understanding of each other’s practice. This means that getting to know each other is important, and it involves the shaping of the roles and identities of the people involved. How do I play my role in the meeting with others in this context? How do they play their role? What is expected from me? This could be learned by the actors by participating in meeting places arranged by the intermediary organisation, such as subject group meetings, seminars and workshops.

In the above narratives, people interact and form their understanding of each other. For example, Lars learns about issues perceived by different parts of the sector, and Victoria discovers Felipe’s research. Niels learns what kind of questions and experiences farmers, advisors and authorities have, concerning the use of subsidiary crops.

However, practices are constantly in a state of tension, due to the continual presence of power, politics and conflict aspects [31]. While perhaps not directly present, this element is inherent in the narrative of the board meeting. Both Christine and Lars refer to discussions on strategic issues and the future development of the intermediary organisation. Strategic discussions in the board could end in decisions to alter the structures of the intermediary organisation and, thereby, the practices.

5.3. Processes

Practice-based research states that while the individual is a carrier and performer of social practices, there is normally space for initiative, creativity, individual performance and adaption [31]. These are the processes that take place in relations between people. In the narratives above, the actors take initiatives against the stable background of the intermediary’s practices. For example, Victoria contacts Felipe about trying the new method against aphids in root crops, starting a process of developing new knowledge about this topic.

While the intermediary organisation provides various kinds of meeting spaces and facilitation by the operating manager, it is up to the participants to take advantage of these opportunities. In fact, the intermediary organisation is dependent on individuals using the possibility of taking initiatives and creating collaborations. Resources of different kinds, e.g., financial, infrastructural, knowledge and social networks, are embedded in structures, which in turn make practices and processes possible. Reciprocally, the practices and processes maintain and reinforce the structures [31]. It is when the practices and processes are carried out, as in, for example, the narratives, that meaning is created which keeps the intermediary organisation going. Thus, the structures provide resources and give legitimacy to the intermediary organisation, but it is through the meetings and the interplay between its members, the practices and processes, that it gains results and recognition.

Practice-based research and process theories highlight the fact that practices are meaning-making, are identity-forming and, at same time, produce the structure [22,31] of the intermediary organisation. While this study has touched upon these aspects, they each constitute interesting areas for further research in connection to collaboration between multiple actors in innovation intermediary organisations.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to understand and explore situations of collaboration between various actors in connection with a university-driven innovation intermediary organisation and how the intermediary organisation facilitates collaboration in the making, and we have reached the following conclusions.

To answer the first research question of how collaboration in the making within the intermediary organization can be understood, we conclude that collaboration in the making is formed in the interplay between structures, practices, and processes between people. While the structures provide legitimacy and resources, the intermediary organisation may be perceived as being constituted by the practices and interactions among its members. The three narratives are examples of unique results emerging from relational processes between people, performed against the background of practices and structures provided by the intermediary organisation.

To answer the second research question of how the intermediary organisation facilitates collaboration in the making, we conclude that the presence of a continuum from fixed to fluid structures enables people to use the different kinds of structures to set their collaboration processes in motion. The fixed structures of the board and working committee allocate the financial resources used for meeting places and projects. The looser structures of, for example, meeting places imply a more flexible interpretational frame, which allows for a larger span of spontaneity and creativity in the processes between people, which in turn can alter the practice and the structure at hand, in sometimes-unpredictable ways [39]. This contributes to a creative tension between activities with firmer and looser interpretational frames [53], which along with the presence of resources allows for people to set their collaboration processes in motion.

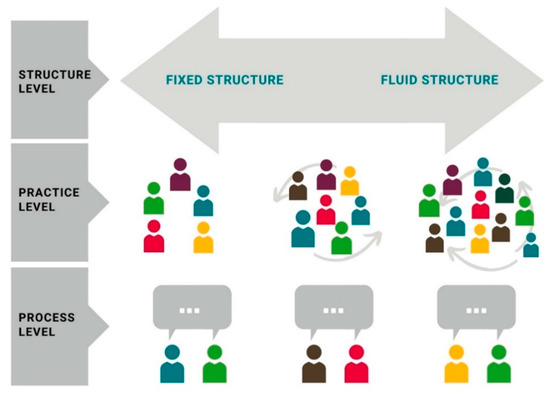

Based on the frame of reference and the analysis of the empirical material, we developed a conceptual model where the structures of the intermediary organisation are translated into practices, against which individuals can develop their collaboration processes; see Figure 2. This implies that the organising of collaboration should focus its attention not only on structures but also on the practices and processes formed between people. It is in the practices that individuals can make meaning of what they do, learn about each other, shape identities, take initiatives, find collaboration partners and develop collaboration processes.

Figure 2.

A conceptual model of the structures, practices and processes of an innovation intermediary organisation. The structures are translated into practices, against which individuals can develop their collaboration processes. This implies that while the structures provide resources, the organising of collaboration should focus its attention not only on structures but also on the practices and processes formed between people.

The results of this study further emphasise the key role of intermediary work, as in, for example, [2,4,15,27]. We propose that the presented conceptual model can help practitioners to understand and model their intermediary work, as well as inspire further research on how to understand the micro-level of collaboration. If we want to understand and develop collaboration, we must have an understanding of collaboration in the making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.B.G. and S.A. with contributions from A.L.; methodology, S.A. with contributions from L.B.G. and A.L.; investigation, L.B.G., S.A. and A.L.; resources, L.B.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.G., S.A. and A.L.; writing—review and editing, L.B.G., S.A. and A.L.; visualisation, L.B.G.; project administration, L.B.G.; funding acquisition, L.B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sparbanksstiftelsen Färs & Frosta/Sparbanken Skåne, SLU Partnership Alnarp, and SLU RådNu—thank you to all.

Acknowledgments

We thank anonymous reviewers of the IFSA Conference and this journal for comments. We thank H. Weiber-Post for help with the graphics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Trencher, G.P.; Yarime, M.; Kharrazi, A. Co-creating sustainability: Cross-sector university collaborations for driving sustainable urban transformations. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; McAdam, R.; McAdam, M. A systematic literature review of university technology transfer from a quadruple helix perspective: Toward a research agenda. R D Manag. 2018, 48, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M.; Tartari, V.; McKelvey, M.; Autio, E.; Broström, A.; D’este, P.; Fini, R.; Geuna, A.; Grimaldi, R.; Hughes, A.; et al. Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, J. Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Boon, W.; Hyysalo, S.; Klerkx, L. Towards a typology of intermediaries in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and a research agenda. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU SCAR AKIS. Preparing for Future AKIS in Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.; Rozakis, S.; Grigoroudis, E. Agri-science to agri-business: The technology transfer dimension. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedwell, W.L.; Wildman, J.L.; DiazGranados, D.; Salazar, M.; Kramer, W.S.; Salas, E. Collaboration at work: An integrative multilevel conceptualization. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajalo, S.; Vadi, M. University-industry innovation collaboration: Reconceptualization. Tecnovation 2017, 62–63, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thune, T. University-industry collaboration: The network embeddedness approach. Sci. Public Policy 2007, 34, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tabbaa, O.; Ankrah, S. ‘Engineered’ university-industry collaboration: A social capital. Perspect. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thune, T.; Gullbrandsen, M. Dynamics of collaboration in university-industry partnerships: Do initial conditions explain development partners? J. Technol. Transf. 2014, 39, 977–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, E.; Rasmussen, E.; Grimaldi, R. How intermediary organizations facilitate university–industry technology transfer: A proximity approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 114, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneel, J.; D’Este, P.; Salter, A. Investigating the factors that diminish the barriers to university-industry collaboration. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Leeuwis, C. Matching demand and supply in the agricultural knowledge infrastructure: Experiences with innovation intermediaries. Food Policy 2008, 33, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilelu, C.W.; Klerkx, L.; Leeuwis, C. Unravelling the role of innovation platforms in supporting co-evolution of innovation: Contributions and tensions in a smallholder dairy development programme. Agric. Syst. 2013, 118, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.; Howells, J.; Meyer, M. Innovation intermediaries and collaboration: Knowledge-based practices and internal value creation. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.; Robinson, S.; Lockett, N. Recognising “open innovation” in HEI-industry interaction for knowledge transfer and exchange. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, M.; Debackere, K. Beyond ‘triple helix’ toward ‘quadruple helix’ models in regional innovation systems: Implications for theory and practice. R D Manag. 2018, 48, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, A.; Lindberg, K.; Mork, B.E.; Nicolini, D.; Raviola, E.; Walter, L. Boundary work among groups, occupations, and organizations: From cartography to process. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 13, 704–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, R.D.; Mowles, C. Strategic Management and Organisational Dynamics: The Challenge of Complexity to Ways of Thinking about Organisations; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, R.; Holt, R. On managerial knowledge. Manag. Learn. 2008, 39, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriotta, G. Organizational Knowledge in the Making: How Firms Create, Use and Institutionalize Knowledge; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard, T. Industry and academia in convergence: Micro-institutional dimensions of R&D collaboration. Technovation 2010, 30, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.R.; Van Every, E.J. The Emergent Organization. Communication as Its Site and Surface; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vaara, E.; Whittington, R. Strategy-as-practice: Taking social practices seriously. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 285–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, L. Responsible innovation through conscious contestation at the interface of agricultural science, policy, and civil society. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustinsson, S.; Ericsson, U.; Rakar, F. Organisation ur Nya och Gamla Perspektiv. Ett Kollage; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, K.; Czarniawska, B. Knotting the action net, or organizing between organizations. Scand. J. Manag. 2006, 22, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukas, H.; Chia, R. On organizational becoming: Rethinking organizational change. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, D. Practice Theory, Work, & Organization: An Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzki, T.R.; Cetina Knorr, K.; von Savigny, E. The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, L.A. Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human Machine Communication; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee, D. Organization Theory. Tension and Change; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Garud, R.; Simpson, B.; Langley, A.; Tsoukas, H. The Emergency of Novelty in Organizations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A.; Tsoukas, H. Introducing perspectives on process organization studies. In Process, Sensemaking and Organizing; Hernes, T., Maitlis, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hernes, T. A Process Theory of Organization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. The Social Psychology of Organizing; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.; Obstfeld, D. Organizing and the Process of Sensemaking. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, T.; Hernes, T. Organizing is both a verb and a noun: Weick meets Whitehead. Organ. Stud. 2006, 27, 1599–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniawska, B. A Theory of Organizing, 2nd ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blix Germundsson, L. SLU Partnership Alnarp: Connecting Academia, Industry and Society. In LTV-Fakultetens Faktablad (LTV Faculty Factsheet) 2020:4; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Alnarp, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, H.E. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Josse-Bass Publishers: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini, D. Zooming in and out: Studying practices by switching theoretical lenses and trailing connections. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 1391–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kärreman, D.; Alvesson, M. Making newsmakers: Conversational identity at work. Organ. Stud. 2001, 22, 59–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniawska, B.; Gagliardi, P. Narratives We Organize by; John Benjamins Pub Co: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, I.; Freshwater, D. Vulnerable story telling: Narrative research in nursing. J. Res. Nurs. 2007, 12, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. Acts of Meaning; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boje, D.M. Narrative Methods for Organizational & Communication Research; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Sköldberg, K. Reflexive Methodology. New Vistas for Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrary, M.; Granovetter, M. The role of venture capital firms in Silicon Valley’s complex innovation network. Econ. Soc. 2009, 38, 326–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriz, A.; Bankins, S.; Molloy, C. Readying a region: Temporally exploring the development of an Australian regional quadruple helix. R D Manag. 2018, 48, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).