The YouTube Marketing Communication Effect on Cognitive, Affective and Behavioural Attitudes among Generation Z Consumers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature and Development of Hypotheses

2.1. YouTube

2.2. Generation Z Cohort

2.3. Consumer Attitudes and Hypothesis Development

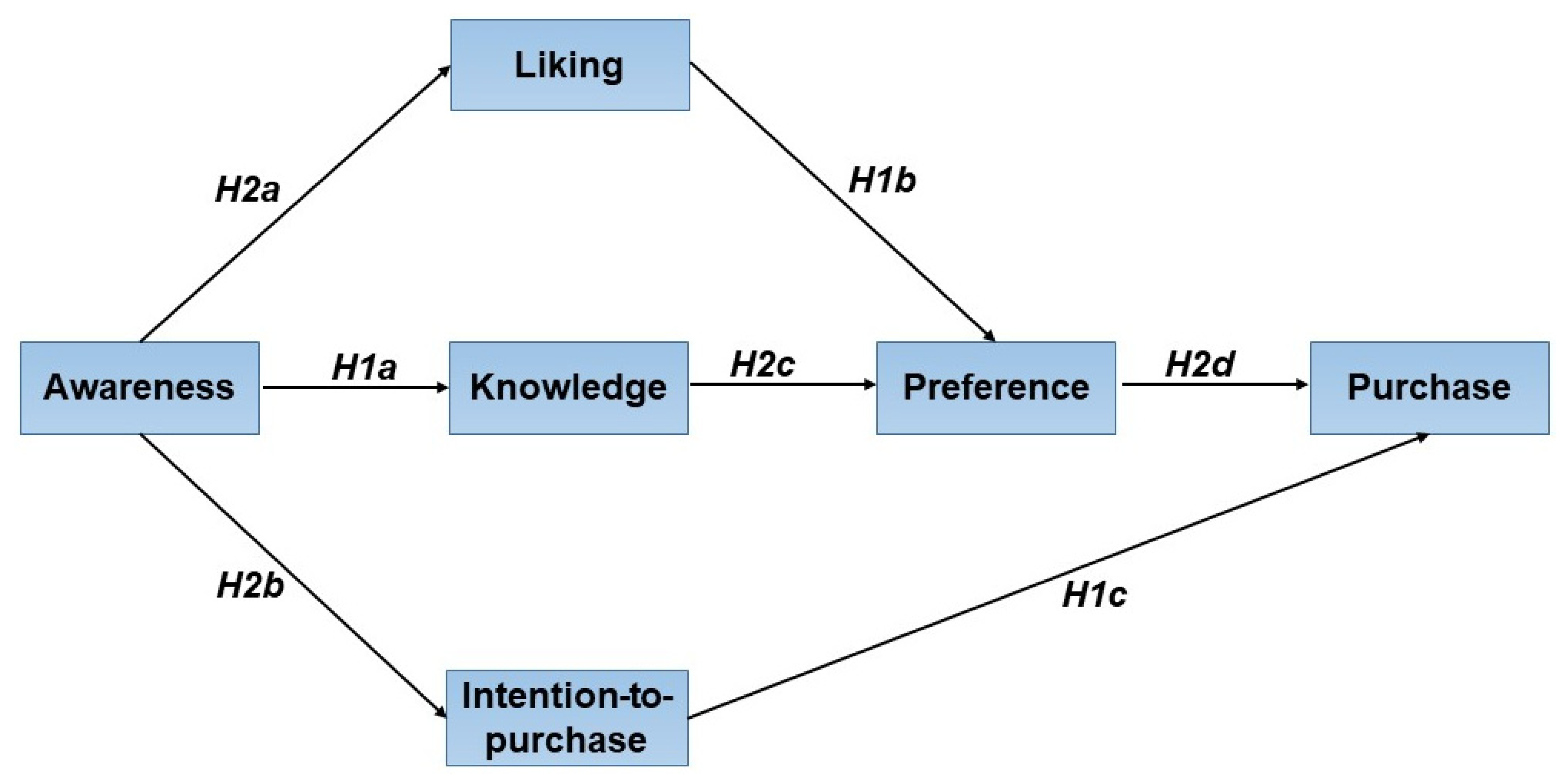

- H1. YMC has a favourable effect on traditional attitudinal associations amid the Generation Z cohort.

- H1a. YMC has a favourable effect on the awareness→knowledge association amid the Generation Z cohort.

- H1b. YMC has a favourable effect on the liking→preference association owing amid the Generation Z cohort.

- H1c. YMC has a favourable effect on the intention-to-purchase→purchase association amid the Generation Z cohort.

- H2. YMC has a positive effect on non-traditional attitudinal associations among the Generation Z cohort.

- H2a. Awareness has a positive effect on liking owing to YMC among the Generation Z cohort.

- H2b. Awareness has a positive effect on intention-to-purchase owing to YMC among the Generation Z cohort.

- H2c. Knowledge has a positive effect on preference owing to YMC among the Generation Z cohort.

- H2d. Preference has a positive effect on purchase owing to YMC among the Generation Z cohort.

2.3.1. Usage Variables’ Hypotheses

- H3. The impact of traditional attitudinal associations differs based on how Generation Z access YMC.

- H3a. The impact of the awareness→knowledge association differs based on how Generation Z access YMC.

- H3b. The impact of the liking→preference association differs based on how Generation Z access YMC.

- H3c. The impact of the intention-to-purchase→purchase association differs based on how Generation Z access YMC.

- H4. The impact of traditional attitudinal associations differs according to the experience (years) of the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H4a. The impact of the awareness→knowledge association differs according to the experience (years) of the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H4b. The impact of the liking→preference association differs according to the experience (years) of the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H4c. The impact of intention-to-purchase→purchase association differs according to the experience (years) of the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H5. The impact of traditional attitudinal associations differs according to the frequency of log-on by the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H5a. The impact of the awareness→knowledge association differs according to the frequency of log-on by the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H5b. The impact of the liking→preference association differs according to the frequency of log-on by the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H5c. The impact of the intention-to-purchase→purchase association differs according to the frequency of log-on by the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H6. The impact of traditional attitudinal associations differs according to the duration of log-on by the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H6a. The impact of the awareness→knowledge association differs according to the duration of log-on by the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H6b. The impact of the liking→preference association differs according to the duration of log-on by the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H6c. The impact of the intention-to-purchase→purchase association differs according to the duration of log-on by the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H7. The impact of traditional attitudinal associations differs according to the number of YT commercials viewed by the Generation Z cohort.

- H7a. The impact of the awareness→knowledge association differs according to the number of YT commercials viewed by the Generation Z cohort.

- H7b. The impact of the liking→preference association differs according to the number of YT commercials viewed by the Generation Z cohort.

- H7c. The impact of the intention-to-purchase→purchase association differs according to the number of YT commercials viewed by the Generation Z cohort.

2.3.2. YouTube Demographic Variables’ Hypotheses

- H8. The impact of traditional attitudinal associations differs according to the gender of the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H8a. The impact of the awareness→knowledge association differs according to the gender of the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H8b. The impact of the liking→preference association differs according to the gender of the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H8c. The impact of the intention-to-purchase→purchase association differs according to the gender of the Generation Z cohort owing to YMC.

- H9. The impact of traditional attitudinal associations differs according to Generation Z’s age owing to YMC.

- H9a. The impact of the awareness→knowledge association differs according Generation Z’s age owing to YMC.

- H9b. The impact of the liking→preference association differs according Generation Z’s age owing to YMC.

- H9c. The impact of the intention-to-purchase→purchase association differs according Generation Z’s age owing to YMC.

- H10. The impact of traditional attitudinal associations differs according to Generation Z’s race owing to YMC.

- H10a. The impact of the awareness→knowledge association differs according to Generation Z’s race owing to YMC.

- H10b. The impact of the liking→preference association differs according to Generation Z’s race owing to YMC.

- H10c. The impact of the intention-to-purchase→purchase association differs according to Generation Z’s race owing to YMC.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Results and Data Analysis

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

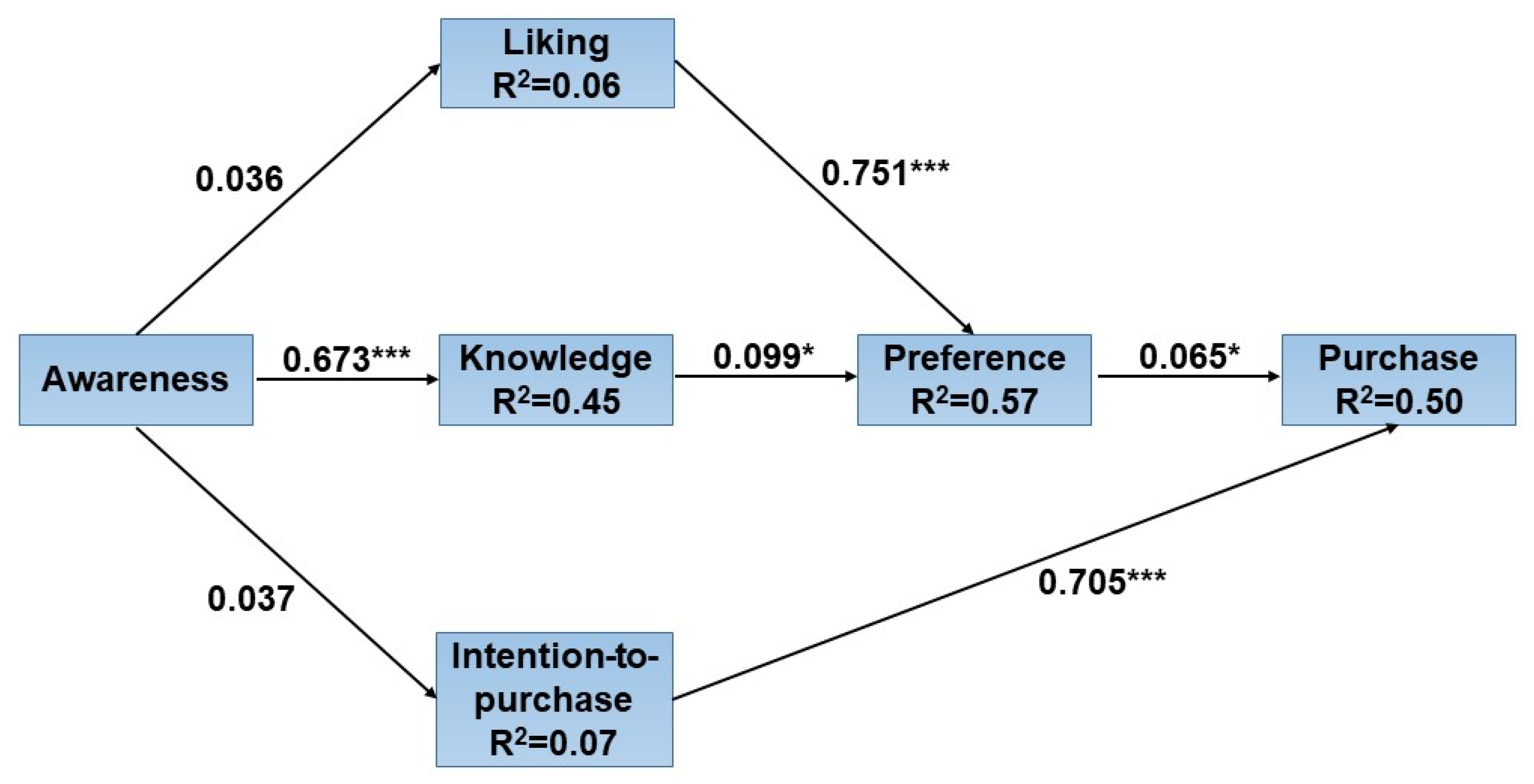

- H1: Traditional attitudinal associations. Figure 2 exhibits the SEM analysis in terms of significance, standardised path coefficients, and variance for the attitudinal association hypotheses. The standardised path coefficients showed significant positive influences for: awareness→knowledge (β = 0.673, p < 0.001), liking→preference (β = 0.751, p < 0.001), and intention-to-purchase→purchase (β = 0.705, p < 0.001) traditional attitudinal associations. Therefore, H1a, H1b, and H1c were supported (refer to Figure 2). Additionally, 45% of the variance due to knowledge was elucidated by awareness amid Generation Z owing to YMC. Knowledge and liking were found to explain 57% of preference’s variance, and preference and intention-to-purchase explained 50% of a purchase’s variance.

- H2: Non-traditional attitudinal associations. No significant influences were found for the awareness→liking (β = 0.036) and awareness→intention-to-purchase (β = 0.037) standardised path coefficients. However, the standardised path coefficients revealed significant positive influences for: knowledge→preference (β = 0.099, p < 0.05), and preference→purchase (β = 0.065, p < 0.05) non-traditional attitudinal associations. Accordingly, H2a and H2b were not supported, whereas H2c and H2d were supported (refer to Figure 2).

- H3: Access. The standardised path coefficients indicated that the devices used to access YT did not have a significant influence on the traditional cognitive (awareness→knowledge), affective (liking→preference), and behavioural (intention-to-purchase→purchase) attitudinal associations due to YMC. Hence, H3a, H3b, and H3c were not supported.

- H4: Experience (years). The standardised path coefficient indicated that awareness had a favourable effect on knowledge amid young consumers who used YT for ≤1 year (β = 0.694, p < 0.05 and p < 0.001) versus those who used YT for 3 years (β = 0647, p < 0.05) and ≥5 years (β = 0.660, p < 0.001). As a result, H4a was supported, while H4b and H4c were not supported.

- H5: Frequency of log-on. The standardised path coefficient also indicated that awareness had a favourable effect on knowledge for young consumers who logged-on to YT daily (β = 0.687, p < 0.05) versus those who logged-on to YT once a week (β = 0.531, p < 0.05). The standardised path coefficient showed that the liking→preference association was more favourable for young consumers who logged-on 2–4 times a month (β = 0.820, p < 0.05) versus those who logged-on to YT once a week (β = 0.717, p < 0.05). Additionally, the standardised path coefficients revealed that intention-to-purchase had a positive influence on purchase for young consumers who logged-on 2–4 times a month (β = 0.765, p < 0.05) versus those who logged-on 2–4 times a week (β = 0.678, p < 0.05). Consequently, H5a, H5b, and H5c were supported.

- H6: Duration of log-on. The standardised path coefficient revealed that the awareness→knowledge association was more positive amid young consumers who spent ≤1 h (β = 0.710, p < 0.05) versus those who spent 3 (β = 0618, p < 0.05) and 4 (β = 0.593, p < 0.05) h logged-on to YT. So, H6a was supported, whereas H6b and H6c were not supported.

- H7: Number of YT commercials viewed. The standardised path coefficient indicated the liking→preference association was more positive for young consumers who viewed 1–5 (β = 0.766, p < 0.05), 6–10 (β = 0.763, p < 0.05), and ≥16 (β = 0.775, p < 0.05) versus those who viewed no (β = 0.689, p < 0.05) YT commercials. The standardised path coefficients also revealed that intention-to-purchase had positive influence on purchase for young consumers who viewed 11–15 (β = 0.733, p < 0.05) versus those who viewed no (β = 0.730, p < 0.05) YT commercials. Accordingly, H7a was not supported, while H7b and H7c were supported.

- H8: Gender. The standardised path coefficients indicated that gender did not result in a significant effect on the cognitive, affective and behavioural attitudinal associations of young consumers due to YMC. Hence, H8a, H8b, and H8c were not supported.

- H9: Age. The standardised path coefficient indicated that the awareness →knowledge was more favourable for young consumers who were aged 13–14 (β = 0.717, p < 0.05) versus those who were aged 15–16 (β = 0.675, p < 0.05) and 17–18 (β = 0.649, p < 0.05) years. The standardised path coefficients also revealed that intention-to-purchase had a positive influence on purchase for young consumers who were aged 13–14 (β = 0.742, p < 0.05) versus those who were aged 15–16 (β = 0.691, p < 0.05) years. Consequently, H9a and H9c were supported, whereas H9b was not supported.

- H10: Race. The standardised path coefficient indicated that the awareness→knowledge association was more favourable for young White consumers (β = 0.717, p < 0.05) versus young Black (β = 0.646, p < 0.05), Coloured (β = 0.658, p < 0.05), and Indian/Asian (β = 0.639, p < 0.05) consumers. The standardised path coefficients also revealed that intention-to-purchase had a positive influence on purchase for White (β = 0.733, p < 0.05) versus Black (β = 0.674, p < 0.05) young consumers. Therefore, H10a and H10c were supported, while H10b was not supported.

5. Discussion

5.1. YMC Influence on Young Consumers’ Attitudes

5.2. YMC Usage Variables’ Influence on Young Consumers’ Attitudes

5.3. YMC Demographic Variables’ Influence on Young Consumers’ Attitudes

6. Conclusions and Contributions to Knowledge and Practice

7. Limitations and Further Research

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stokes, R. eMarketing: The Essential Guide to Marketing in a Digital World, 6th ed.; Quirk Education and Red & Yellow: Cape Town, South Africa, 2017; ISBN 9788578110796. [Google Scholar]

- Foye, L. Global Ad Spend Will Reach $37bn in the Next Five Years. Available online: http://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/1/12/172893.html#more (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Mok, R.K.P.; Bajpai, V.; Dhamdhere, A.; Claffy, K.C. Revealing the load-balancing behavior of YouTube traffic on interdomain links. In Passive and Active Measurement; Beverly, R., Smaragdakis, G., Feldmann, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viertola, W. To What Extent Does YouTube Marketing Influence the Consumer Behaviour of a Young Target Group; Metropolia University of Applied Sciences: Helsinki, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K. 57 Fascinating and Incredible YouTube Statistics. Available online: https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/youtube-stats/ (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Chadha, R. Marketers Think YouTube, Facebook Are Most Effective Video Ad Platforms (Surprise!). Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/marketers-think-youtube-facebook-the-most-effective-video-ad-platforms-surprise?ecid=NL1002 (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Campaign Monitor. The Ultimate Guide to Marketing to Gen Z in 2019. Available online: https://www.campaignmonitor.com/resources/guides/guide-to-gen-z-marketing-2019/?g&utm_medium=display&utm_source=emarketer&utm_campaign=040119 (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Koch, L. Gen Z Goes to the ’Gram for New Products, Brand Engagement. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/gen-z-goes-to-the-gram-for-new-products?ecid=NL1014 (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Mishra, A.; Maheswarappa, S.S.; Maity, M.; Samu, S. Adolescent’s eWOM intentions: An investigation into the roles of peers, the Internet and gender. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.T. Mobile advertising to Digital Natives: Preferences on content, style, personalization, and functionality. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J. Aggregate Advertising Models: State of the Art. Oper. Res. 1979, 27, 629–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barry, T.M. The development of the hierarchy of effects: An historical perspective. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 1987, 10, 251–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavidge, R.J.; Steiner, G.A. A model of predictive measurement of advertising effectiveness. J. Mark. 1961, 25, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimp, T.A. Attitude toward the ad as a mediator of consumer brand choice. J. Advert. 1981, 10, 9–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Vanhonacker, W.R. The Hierarchy of Advertising Effects: An Aggregate Field Test of Temporal Precedence; Columbia Business School: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, T.E.; Howard, D.J. A review and critique of the hierarchy of effects in advertising. Int. J. Advert. 1990, 9, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.; Stayman, D.M. Antecedents and consequences of attitude toward the ad: A meta-analysis. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.S.; Hsiao, K.L. YouTube stickiness: The needs, personal, and environmental perspective. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Do People Purchase What They Viewed from YouTube? The Influence of Attitude and Perceived Credibility of User-Generated Content on Purchase Intention; The Florida State University: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, J.; Manickavasagam, J. User Disposition and Attitude towards Advertisements Placed in Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter and YouTube. J. Electron. Commer. Organ. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chungviwatanant, T.; Prasongsukam, K.; Chungviwatanant, S. A study of factors that affect consumer’s attitude toward a “skippable in-stream ad” on YouTube. Au Gsb E J. 2016, 9, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani, M.; Niaki, M.K.; Ramezani, I.; Sali, R. Evaluating the influence of YouTube advertising for attraction of young customers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 59, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Watkins, B. YouTube vloggers’ influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5753–5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westenberg, W. The Influence of YouTubers on Teenagers: A Descriptive Research about the Role YouTubers Play in the Life of Their Teenage Viewers; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Mao, E. From online motivations to ad clicks and to behavioral intentions: An empirical study of consumer response to social media advertising. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.S.; Magno, G.; Meira, W.; Almeida, V.; Hartung, P.; Doneda, D. Characterizing videos, audience and advertising in youtube channels for kids. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bartozik-Purgat, M.; Filimon, N. Patterns of YouTube uses in a cross-cultural context: An exploratory approach focused on gender and age. Adv. Sociol. Res. 2017, 22, 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Göbel, F.; Meyer, A.; Ramaseshan, B.; Bartsch, S. Consumer responses to covert advertising in social media. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2017, 35, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Singh, S.; Sinha, P. Multimedia tool as a predictor for social media advertising—A YouTube way. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 18557–18568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, L.; Stanic, N. Do Big Laughs and Positive Attitudes Sell? An Examination of Sponsored Content on YouTube, and How Entertainment and Attitude Influence Purchase Intentions in Millennial Viewers; Halmstad University: Halmstad, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Hansen, S.S. Source Credibility in Consumer-Generated Advertising in Youtube: The Moderating Role of Personality. Curr. Psychol. 2017, 36, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.R. Effectiveness of YouTube Advertising: A Study of Audience Analysis; Rochester Institute of Technology: Rochester, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.C.; Huang, C.H.; Yang, C.; Yang, S.Y. Consumer attitudes toward online video advertisement: YouTube as a platform. Kybernetes 2017, 46, 840–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baramidze, T. The Effect of Influencer Marketing on Customer Behaviour. The Case of YouTube Influencers in Makeup Industry; Vytautas Magnus University: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, N.C.; Zhang, R.; Ha, L. Does valence of product review matter?: The mediating role of self-effect and third-person effect in sharing YouTube word-of-mouth (vWOM). J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2019, 13, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xie, Q. Measuring the content characteristics of videos featuring augmented reality advertising campaigns. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Lam, T.; Pettigrew, S.; Tait, R.J. Alcohol marketing on YouTube: Exploratory analysis of content adaptation to enhance user engagement in different national contexts. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horáková, Z. The Channel of Influence? YouTube Advertising and the Hipster Phenomenon; Charles University: Prague, Czechia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klobas, J.E.; McGill, T.J.; Moghavvemi, S.; Paramanathan, T. Compulsive YouTube usage: A comparison of use motivation and personality effects. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujur, F.; Singh, S. Emotions as predictor for consumer engagement in YouTube advertisement. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2018, 15, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L. Parasocial interaction in the digital age: An examination of relationship building and the effectiveness of YouTube Celebrities. J. Soc. Media Soc. 2018, 7, 280–294. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.; Hoe Ng, S.; Omar, A.; Karupaiah, T. What’s on YouTube? A case study on food and beverage advertising in videos targeted at children on social media. Child. Obes. 2018, 14, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vingilisa, E.; Yildirim-Yeniera, Z.; Vingilis-Jaremkob, L.; Seeleya, J.; Wickensc, C.M.; Grushkaa, D.H.; Fleiterd, J. “Young male drivers’ perceptions of and experiences with YouTube videos of risky driving behaviors. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 120, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitceva, E. The Fight for Customers’ Attention: YouTube as an Advertising Platform; Kajaani University of Applied Sciences: Kajaani, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, T.; Agarwal, B. Empirical study on perceived value and attitude of Millennials towards social media advertising: A structural equation modelling approach. Vision 2019, 23, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R.G.; Edu, T.; Negricea, I.C. YouTube marketing communication demographic and usage variables influence on Gen Y’s cognitive attitudes in South Africa and Romania. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 85, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R.G.; Petroșanu, D.M.; Negricea, I.C.; Edu, T. Effect of YouTube marketing communication on converting brand liking into preference among Millennials regarding brands in general and sustainable offers in particular: Evidence from South Africa and Romania. Sustainability 2019, 11, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, N.J.; Hoy, M.G.; Childers, C.C. Parenting ‘YouTube Natives’: The impact of pre-roll advertising and text disclosures on parental responses to sponsored child influencer videos. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, D. YouTube advertising value and its effects on purchase intention. J. Glob. Bus. Insights 2019, 4, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Xie, Q.; Feng, Y.; Kim, W. Does non-hard-sell content really work? Leveraging the value of branded content marketing in brand building. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2019, 28, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. Do social networking platforms promote service quality and purchase intention of customers of service-providing organisations? J. Manag. 2019, 38, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. Role of social networking platforms as tool for enhancing the service quality and purchase intention of customers in Islamic country. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 10, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma, P.; Aloini, D. How does brand-related user-generated content differ across social media? Evidence reloaded. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R.G.; Edu, T.; Negricea, I.C.; Zaharia, R.M. Modelling the effect of YouTube as an advertising medium on converting intention-to-purchase into purchase. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2020, 19, 112–132. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.C.; Omran, B.A.; Cobanoglu, C. Generation Y’s positive and negative eWOM: Use of social media and mobile technology. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 732–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Z.; Ahmad, M.; Bakarc, A.R.A. Reflections of entrepreneurs of small and medium-sized enterprises concerning the adoption of social media and its impact on performance outcomes: Evidence from the UAE. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukerjee, K.; Shaikh, A. Impact of customer orientation on word-of-mouth and cross-buying. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilova, M.; Livingstone, S.; Kardefelt-Winther, D. Global kids online: Researching children’s rights globally in the digital age. Glob. Stud. Child. 2016, 6, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Styvén, M.E.; Foster, T. Who am I if you can’t see me? The “self” of young travellers as driver of eWOM in social media. J. Tour. Futures 2018, 4, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Zhang, Q. Influence of parasocial relationship between digital celebrities and their followers on followers’ purchase and electronic word-of-mouth intentions, and persuasion knowledge. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Choi, H. Predictors of electronic word-of-mouth behaviour on social networking sites in the United States and Korea: Cultural and social relationship variables. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 94, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Garg, A.; Prasad, S. Purchase decision of generation Y in an online environment. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesame, Z. Vision and Practice: The South African Information Society Experience. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2013, 5, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Duh, H.; Struwig, M. Justification of generational cohort segmentation in South Africa. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2015, 10, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Hoefnagels, A.; Migchels, N.; Kabadayi, S.; Gruber, T.; Loureiro, Y.K.; Solnet, D. Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- YouTube. For Press. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/intl/en-GB/about/press/ (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Statista. YouTube—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/2019/youtube/ (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Wendt, L.M.; Griesbaum, J.; Kölle, R. Product advertising and viral stealth marketing in online videos: A description and comparison of comments on YouTube. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 68, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YouTube. Analytics Basics. Available online: https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/1714323?hl=en (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- McCrindle, M.; Wolfinger, E. The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations; University of South Wales Press: New South Wales, AU, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781742240947. [Google Scholar]

- Van Loggerenberg, M.; Lechuti, T. Generation Z—Chasing Butterflies (Part 1). Available online: http://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/82/177163.html#more (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- de Coninck, L. The uneasy boundary work of ‘coconuts’ and ‘black diamonds’: Middle-class labelling in post-apartheid South Africa. Crit. Afr. Stud. 2018, 10, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, J.; Santos, M.; Westwater, G. OMD Media Facts. 2018. Available online: http://www.omd.co.za/media_facts/OMD_Media_Facts_2018.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Thompson, R. The ’ennial tribes: Understanding Generation Y and Generation Z South Africans. Available online: http://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/19/176153.html (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Duffett, R.G.; van der Heever, I.C.; Bell, D. Black Economic Empowerment progress in the advertising industry in Cape Town: Challenges and benefits. S. Afr. Bus. Rev. 2009, 13, 86–118. [Google Scholar]

- Belch, G.E.; Belch, M.A. Advertising & Promotion an Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective, 11th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 9789814575119. [Google Scholar]

- Ducoffe, R.H. Advertising value and advertising on the Web. J. Advert. Res. 1996, 36, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brackett, L.K.; Carr, B.N. Cyberspace advertising vs. other media: Consumer vs. mature student attitudes. J. Advert. Res. 2001, 41, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, E.H.F.H. Young Saudi females and social media advertising. Khartoum Univ. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 10, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R.; Reyes-Menendez, A.; Palos-Sanchez, P. Are Black Friday deals worth it? Mining Twitter users’ sentiment and behavior response. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Y.-Q.; Kanjanamekanant, K. No trespassing: Exploring privacy boundaries in personalized advertisement and its effects on ad attitude and purchase intentions on social media. Inf. Manag. 2020, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R.G.; Wakeham, M. Social media marketing communications’ effect on attitudes among Millennials in South Africa. Afr. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 8, 20–44. [Google Scholar]

- Duffett, R.G. Effect of Gen Y’s affective attitudes towards facebook marketing communications in South Africa. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 68, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duffett, R.G. Facebook advertising’s influence on intention-to-purchase and purchase amongst Millennials. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 498–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R.G. The influence of Facebook advertising on cognitive attitudes amid Generation Y. Electron. Commer. Res. 2015, 15, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duffett, R.G. Effect of instant messaging advertising on the hierarchy-ofeffects model amid teenagers in South Africa. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2016, 72, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R.G. Influence of Facebook commercial communications on Generation Z’s attitudes in South Africa. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2017, 81, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duffett, R.G. Influence of social media marketing communications on young consumers’ attitudes. Young Consum. 2017, 18, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kite, J.; Gale, J.; Grunseit, A.; Li, V.; Bellew, W.; Bauman, A. From awareness to behaviour: Testing a hierarchy of effects model on the Australian Make Healthy Normal campaign using mediation analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, M.; Schnurbus, J.; Haupt, H.; Dorner, V.; Landherr, A.; Probst, F. Dynamic effects of user- and marketer-generated content on consumer purchase behavior: Modeling the hierarchical structure of social media websites. Decis. Support Syst. 2018, 113, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntunen, M.; Ismagilova, E.; Oikarinen, E. B2B brands on Twitter: Engaging users with a varying combination of social media content objectives, strategies, and tactics. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S. Mobile shopping among young consumers: An empirical study in an emerging market. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 930–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, M.A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kumar, V.; Davies, G.; Rana, N.; Baabdullah, A. Purchase intention in an electronic commerce environment: A trade-off between controlling measures and operational performance. Inf. Technol. People 2018, 32, 1345–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khoi, N.H.; Tuu, H.H.; Olsen, S.O. The role of perceived values in explaining Vietnamese consumers’ attitude and intention to adopt mobile commerce. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 1112–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molinillo, S.; Navarro-García, A.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Japutra, A. The impact of affective and cognitive app experiences on loyalty towards retailers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, M.H.A.; Jiang, Y.; Miao, M.; Naqvi, M.H. The effect of social influence, trust, and entertainment value on social media use: Evidence from Pakistan. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, H.D.; Brown, J.K.; Clarke, T.C. Measuring Advertising Results; National Industrial Conference Board: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall, L.V. Consumer Acceptance Theory. In Theory in Marketing; Cox, R., Alderson, W., Shapiro, S.J., Eds.; Richard D. Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1964; pp. 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Zambodla, N. Millennials Are Not a Homogenous Group. Available online: http://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/424/172113.html#more (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- Li, H.; Lo, H.Y. Do You Recognize Its Brand? The Effectiveness of Online In-Stream Video Advertisements. J. Advert. 2015, 44, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padayachee, K. The myths and realities of generational cohort theory on ICT integration in education: A South African perspective. Afr. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 10, 54–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mir, I.A.; Rehnam, K.U. Factors affecting consumer attitudes and intentions toward user-generated product content on YouTube. Manag. Mark. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 2013, 8, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, R.W. Communicating across age-groups: Variance in consumer attitudes from tweenagers to adults. Young Consum. 2016, 16, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, H.; Okoe, A.F. Consumers’ attitude towards social media advertising and their behavioural response. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2015, 9, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzer, D.J.; de Meyer, C.F. Trials and tribulations: Marketing in modern South Africa. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2013, 25, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices, 2nd ed.; University of South Florida Tampa Bay Open Access Textbooks: Tampa, FL, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781475146127. [Google Scholar]

- Haydam, N.; Mostert, T. Marketing Research for Managers, 2nd ed.; African Paradigms Marketing Facilitators: Cape Town, South Africa, 2018; ISBN 9780620780971. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa 2016. Community Survey. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=6283 (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780335242399. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variable Sand Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Hong, I.B. Predicting positive user responses to social media advertising: The roles of emotional appeal, informativeness, and creativity. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sago, B. Factors influencing social media adoption and frequency of use: An examination of Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and Google+. Int. J. Bus. Commer. 2013, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A.; Pagnattaro, M. Beyond millennials: Engaging generation Z in business law classes. J. Leg. Stud. Educ. 2017, 34, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.F.; Vong, S. Virality over youtube: An empirical analysis. Internet Res. 2014, 24, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, P.; Melancon, J. Gender and live-streaming: Source credibility and motivation. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, K. Accepting the challenges of social media research. Online Inf. Rev. 2015, 39, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Wang, R.; Chan-Olmsted, S. Factors affecting YouTube influencer marketing credibility: A heuristic-systematic model. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Usage Variables | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Mobile device | 1430 | 38.1 |

| PC | 428 | 11.4 | |

| Mobile device and PC | 1892 | 50.5 | |

| Experience (years) | ≤1 year | 512 | 13.7 |

| 2 years | 890 | 23.7 | |

| 3 years | 977 | 26.1 | |

| 4 years | 643 | 17.1 | |

| ≥5 years | 728 | 19.4 | |

| Frequency of log-on | Daily | 2428 | 64.7 |

| 2–4 times a week | 663 | 17.7 | |

| Once a week | 343 | 9.1 | |

| 2–4 times a month | 170 | 4.5 | |

| Once a month | 146 | 3.9 | |

| Duration of log-on | ≤1 h | 1351 | 36.0 |

| 2 h | 962 | 25.7 | |

| 3 h | 549 | 14.6 | |

| 4 h | 300 | 8.0 | |

| ≥5 h | 588 | 15.7 | |

| YT commercial viewership # | None | 1333 | 35.5 |

| 1–5 | 824 | 22.0 | |

| 6–10 | 634 | 16.9 | |

| 11–15 | 397 | 10.6 | |

| ≥16 | 562 | 15.0 | |

| Demographic variables | |||

| Gender | Male | 1831 | 48.8 |

| Female | 1919 | 51.2 | |

| Age | 13–14 | 808 | 21.5 |

| 15–16 | 1370 | 36.5 | |

| 17–18 | 1572 | 41.9 | |

| Race | White | 901 | 24.0 |

| Black | 1060 | 28.3 | |

| Coloured | 1519 | 40.5 | |

| Indian/Asian | 270 | 7.2 | |

| Attitude Stages | Factor Loadings | AVE | CR | Cronb.’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | ||||

| YMC are effective in creating awareness of brands | 0.734 | 0.550 | 0.829 | 0.743 |

| YMC alerts me to new company offerings | 0.800 | |||

| I have become aware of new YMC | 0.806 | |||

| YMC get my attention towards certain brands | 0.611 | |||

| Knowledge | ||||

| Ads on YT are effective in providing information about brands | 0.690 | 0.585 | 0.849 | 0.775 |

| YMC are a good source of knowledge | 0.790 | |||

| I use YMC to find new information about products | 0.830 | |||

| YMC provide me with valuable product knowledge | 0.730 | |||

| Liking | ||||

| YMC has made me like the brands more | 0.757 | 0.546 | 0.877 | 0.851 |

| YMC adds to the enjoyment of using YT | 0.818 | |||

| YMC are likeable and pleasant | 0.800 | |||

| YMC are entertaining and fun | 0.806 | |||

| YT has a positive influence on me liking advertised products | 0.644 | |||

| YMC has made me like the products more | 0.574 | |||

| Preference | ||||

| I look for products that are advertised on YT | 0.660 | 0.536 | 0.874 | 0.838 |

| YMC are relevant to me and my interests | 0.680 | |||

| Ads on YT are effective in stimulating my preference in brands | 0.790 | |||

| YMC are effective in gaining my interest in products | 0.790 | |||

| I prefer brands that are promoted on YT | 0.760 | |||

| YMC have a positive effect on my preference for brands | 0.707 | |||

| Intention-to-purchase | ||||

| I will buy products that are advertised on YT in the near future | 0.819 | 0.541 | 0.821 | 0.725 |

| I desire to buy products that are promoted on YT | 0.861 | |||

| YMC increase purchase intent of featured brands | 0.626 | |||

| I would buy products that are advertised on YT if I had the money | 0.599 | |||

| Purchase | ||||

| I purchase products that are featured on YT | 0.634 | 0.565 | 0.885 | 0.848 |

| YMC positively affect my purchase behaviour | 0.755 | |||

| Ads on YT help to make me loyal to the promoted products | 0.810 | |||

| YMC favourably affect my purchase actions | 0.840 | |||

| I purchase products that are promoted on YT | 0.780 | |||

| YMC positively affect my buying actions | 0.660 | |||

| Awareness | 0.742 | |||||

| Knowledge | 0.430 | 0.765 | ||||

| Liking | 0.119 | 0.548 | 0.739 | |||

| Preference | 0.329 | 0.163 | 0.448 | 0.732 | ||

| Intention-to-purchase | 0.035 | 0.141 | 0.048 | 0.429 | 0.736 | |

| Purchase | 0.047 | 0.110 | 0.113 | 0.327 | 0.244 | 0.751 |

| Independent Variables | Awareness→ Knowledge | Liking→ Preference | Intention-to-Purchase→Purchase | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usage Variables | β | Sig | β | Sig | β | Sig | |

| Access | Mobile device (1) | 0.655 | - | 0.740 | - | 0.694 | - |

| PC (2) | 0.647 | 0.766 | 0.738 | ||||

| Mobile device and PC (3) | 0.694 | 0.756 | 0.708 | ||||

| Experience (years) | ≤1 year (1) | 0.694 | p < 0.05 (1)–(3) p < 0.001 (1)–(5) | 0.747 | - | 0.725 | - |

| 2 years (2) | 0.691 | 0.740 | 0.700 | ||||

| 3 years (3) | 0.647 | 0.731 | 0.704 | ||||

| 4 years (4) | 0.682 | 0.761 | 0.691 | ||||

| ≥5 years (5) | 0.660 | 0.783 | 0.709 | ||||

| Frequency of log-on | Daily (1) | 0.687 | p < 0.05 (1)–(3) | 0.757 | p < 0.05 (4)–(3) | 0.707 | p < 0.05 (4)–(2) |

| 2–4 times a week (2) | 0.641 | 0.757 | 0.678 | ||||

| Once a week (3) | 0.531 | 0.717 | 0.736 | ||||

| 2–4 times a month (4) | 0.682 | 0.820 | 0.765 | ||||

| Once a month (5) | 0.665 | 0.778 | 0.633 | ||||

| Duration of log-on | ≤1 h (1) | 0.710 | p < 0.05 (1)–(3 & 4) | 0.759 | - | 0.723 | - |

| 2 h (2) | 0.657 | 0.732 | 0.702 | ||||

| 3 h (3) | 0.618 | 0.741 | 0.686 | ||||

| 4 h (4) | 0.593 | 0.751 | 0.667 | ||||

| ≥5 h (5) | 0.698 | 0.766 | 0.711 | ||||

| YT commercial viewership # | None (1) | 0.689 | - | 0.730 | p < 0.05 (2, 3 & 5)–(1) | 0.689 | p < 0.05 (4)–(1) |

| 1–5 (2) | 0.643 | 0.766 | 0.702 | ||||

| 6–10 (3) | 0.718 | 0.763 | 0.731 | ||||

| 11–15 (4) | 0.647 | 0.733 | 0.733 | ||||

| ≥16 (5) | 0.646 | 0.775 | 0.699 | ||||

| Demographic variables | |||||||

| Gender | Male (1) | 0.669 | - | 0.754 | - | 0.717 | - |

| Female (2) | 0.677 | 0.748 | 0.694 | ||||

| Age | 13–14 (1) | 0.717 | p < 0.05 (1)–(2 & 3) | 0.724 | - | 0.742 | p < 0.05 (1)–(2) |

| 15–16 (2) | 0.675 | 0.757 | 0.691 | ||||

| 17–18 (3) | 0.649 | 0.756 | 0.694 | ||||

| Race | White (1) | 0.717 | p < 0.05 (1)–(2, 3 & 4) | 0.726 | - | 0.733 | p < 0.05 (1)–(2) |

| Black (2) | 0.646 | 0.765 | 0.674 | ||||

| Coloured (3) | 0.658 | 0.752 | 0.710 | ||||

| Indian/Asian (4) | 0.639 | 0.756 | 0.693 | ||||

| Hypothesis | Sub-Hypothesis | Significance | Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H1a | p < 0.001 | Yes |

| H1b | p < 0.001 | Yes | |

| H1c | p < 0.001 | Yes | |

| H2 | H2a | - | No |

| H2b | - | No | |

| H2c | p < 0.05 | Yes | |

| H2d | p < 0.05 | Yes | |

| H3 | H3a | - | No |

| H3b | - | No | |

| H3c | - | No | |

| H4 | H4a | p < 0.001 | Yes |

| H4b | - | No | |

| H4c | - | No | |

| H5 | H5a | p < 0.05 | Yes |

| H5b | p < 0.05 | Yes | |

| H5c | p < 0.05 | Yes | |

| H6 | H6a | p < 0.05 | Yes |

| H6b | - | No | |

| H6c | - | No | |

| H7 | H7a | - | No |

| H7b | p < 0.05 | Yes | |

| H7c | p < 0.05 | Yes | |

| H8 | H8a | - | No |

| H8b | - | No | |

| H8c | - | No | |

| H9 | H9a | p < 0.05 | Yes |

| H9b | - | No | |

| H9c | p < 0.05 | Yes | |

| H10 | H10a | p < 0.05 | Yes |

| H10b | - | No | |

| H10c | p < 0.05 | Yes |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duffett, R. The YouTube Marketing Communication Effect on Cognitive, Affective and Behavioural Attitudes among Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125075

Duffett R. The YouTube Marketing Communication Effect on Cognitive, Affective and Behavioural Attitudes among Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):5075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125075

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuffett, Rodney. 2020. "The YouTube Marketing Communication Effect on Cognitive, Affective and Behavioural Attitudes among Generation Z Consumers" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 5075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125075

APA StyleDuffett, R. (2020). The YouTube Marketing Communication Effect on Cognitive, Affective and Behavioural Attitudes among Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability, 12(12), 5075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125075