Organizational Support and Adaptive Performance: The Revolving Structural Relationships between Job Crafting, Work Engagement, and Adaptive Performance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Research Framework and Hypotheses Development

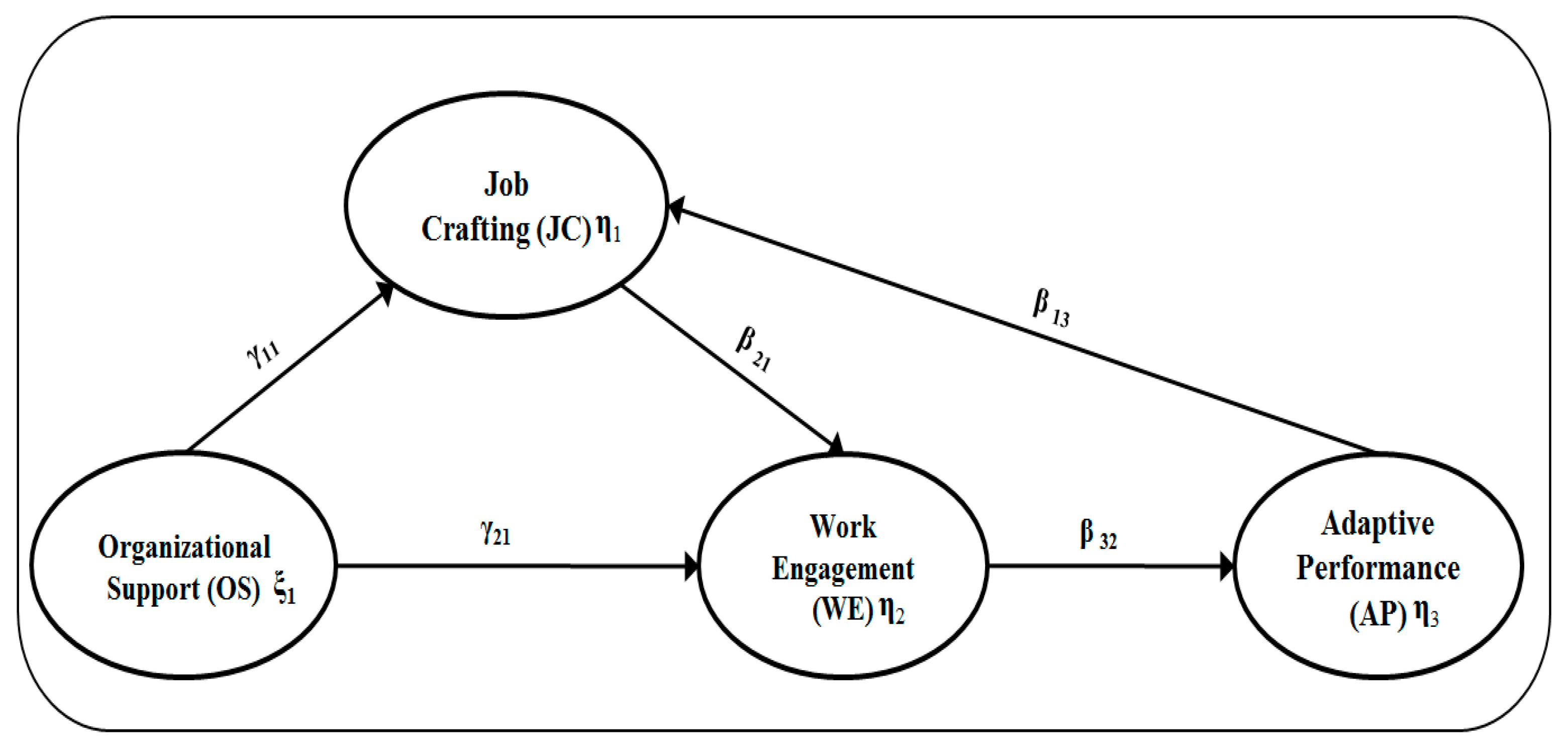

2.1. Conceptual Research Framework

2.2. Organizational Support

2.3. Job Crafting

2.4. Work Engagement

2.5. Adaptive Performance

- creative problem solving,

- handling ambiguous/unintended work situations,

- mastering tasks, technical tools, and work procedures,

- maintaining adaptive interpersonal relationships,

- showing cultural adaptability,

- demonstrating physical adaptability.

2.6. Mediating Relationships between Variables

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. CMB, Normality, Reliability, and Correlation

4.2. Model Evaluation

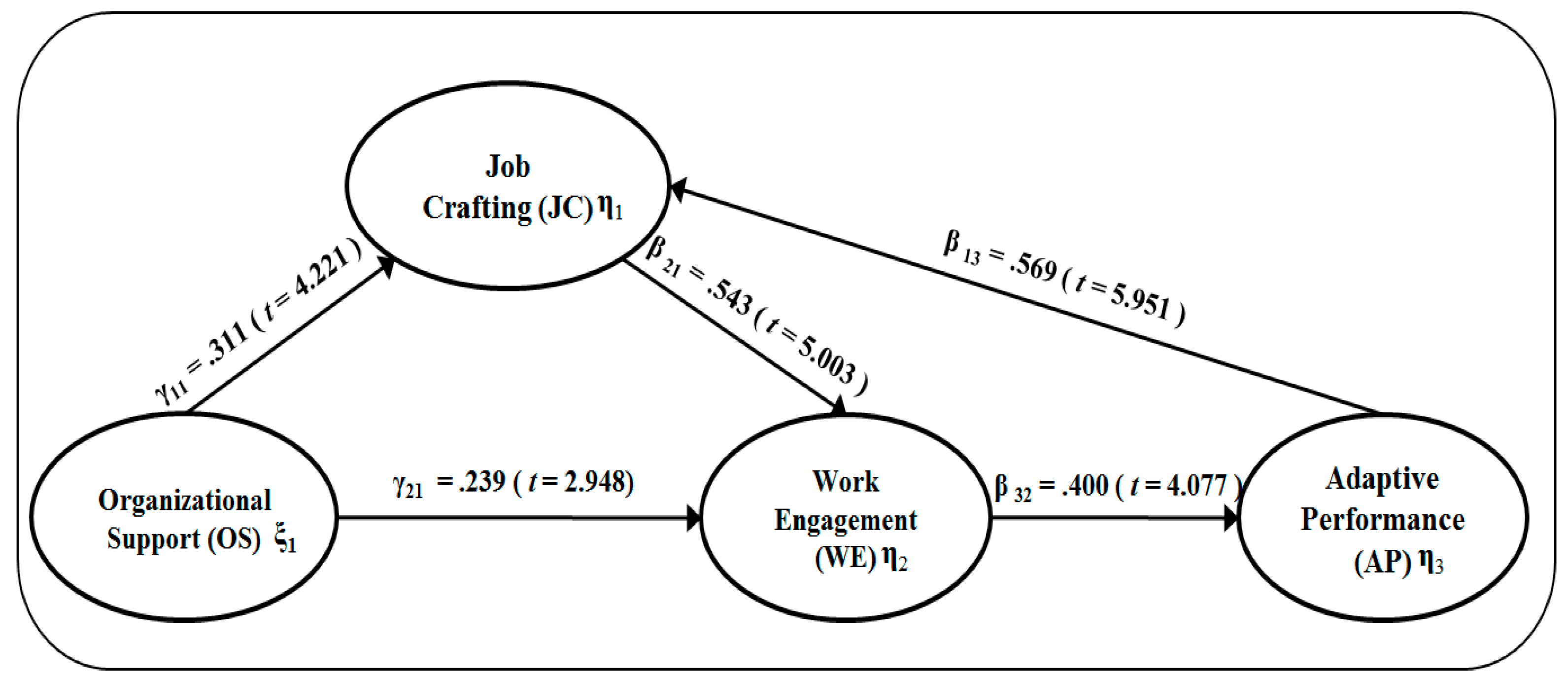

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heinze, K.; Heinze, J. Individual innovation adoption and the role of organizational culture. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 561–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Khan, G.F.; Wood, J.; Mahmood, M.T. Employee engagement for sustainable organizations: Keyword analysis using social network analysis and burst detection approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, W.; Park, J. Examining structural relationships between work engagement, organizational procedural justice, knowledge sharing, and innovative work behavior for sustainable organizations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sweet, K.M.; Witt, L.A.; Shoss, M.K. The interactive effect of leader-member exchange and perceived organizational support on employee adaptive performance. J. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 15, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Dierdorff, E.C.; Jensen, J.M. Crafting in context: Exploring when job crafting is dysfunctional for performance effectiveness. J. Appl. Psycho. 2018, 103, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikangas, A. Job crafting profiles and work engagement: A person-centered approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 106, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vande Griek, O.; Clauson, M.; Eby, L.; Weng, Q. Organizational career growth and proactivity: A typology for individual career development. J. Career Dev. 2020, 47, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Dutton, J.E.; Wrzesniewski, A. Job crafting and meaningful work. In Purpose and Meaning in the Workplace; Dik, B.J., Byrne, Z.S., Steger, M.F., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 81–104. ISBN 9781433813146. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Blanc, P.L.; Lu, C.Q. Crafting a job in ‘tough times’: When being proactive is positively related to work attachment. Human Performance Management. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 91, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, D.W.; Cortina, J.M.; Luchman, J. Adaptive and citizenship-related behaviors at work. In Handbook of Employee Selection; Farr, J.L., Tippins, N.T., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group: Hove, UK, 2010; pp. 463–487. [Google Scholar]

- Tett, R.P.; Burnett, D.D. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 50, 558–577. [Google Scholar]

- Ployhart, R.E.; Turner, S.F. Organizational adaptability. In Organization and Management Series, Individual Adaptability to Changes at Work; Chan, D., Ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Milton Park, UK, 2014; pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidan, A.N.; Abdul Hamid, S.N.; Ahmad, F. Mediating influence of work engagement between person-environment fit and adaptive performance: A conceptual perspective in Malaysia public hospitals. J. Bus. Soc. Rev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 4, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demir, K. The effect of organizational justice and perceived organizational support on organizational citizenship behaviors: The mediating role of organizational identification. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2015, 15, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uppal, N.; Mishra, S.K. Moderation effects of personality and organizational support on the relationship between prior job experience and academic performance of management students. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 39, 1022–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, M.A. Comments on “Pareto weights as wedges in two-country models” by D. Backus, C. Coleman, A. Ferriere and S. Lyon. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2016, 72, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, Y. Crafting employee trust: From authenticity, transparency to engagement. J. Commun. Manag. 2018, 22, 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sleebos, D.M.; Maduro, V. Uncovering the underlying relationship between transformational leaders and followers’ task performance. J. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 13, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D.; van Rhenen, W. Job crafting at the team and individual level: Implications for work engagement and performance. Group. Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Tims, M.; Derks, D. Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jundt, D.K.; Shoss, M.K.; Huang, J.L. Individual adaptive performance in organizations: A review. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, S53–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakos, E.D.; Arad, S.; Donovan, M.A.; Plamondon, K.E. Adaptability in the workplace; Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. J. Appl. Psycho. 2000, 85, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job crafting in changing organizations: Antecedents and implications for exhaustion and performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gordon, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Bipp, T. Job crafting and performance of Dutch and American health care professionals. J. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 14, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.C.W.; Arts, R.; Demerouti, E. The crossover of job crafting between coworkers and its relationship with adaptivity. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 25, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sulea, C.; Virga, D.; Maricutoiu, L.P.; Schaufeli, W.; Dumitru, C.Z.; Sava, F.A. Work engagement as mediator between job characteristics and positive and negative extra-role behaviors. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Babcock-Roberson, M.E.; Strickland, O.J. The relationship between charismatic leadership, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Psychol. 2010, 144, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneesriwongul, W.; Dixon, J.K. Instrument translation process: A methods review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 48, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S. Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Sim, W. A study on the impact of leader’s authenticity on the job crafting of employees and its process. Korean J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 36, 131–162. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.; Salanova, M.; Gonzales, R.; Bakker, A. The measurement of burnout and engagement: A confirmatory analysis. J. Happiness. Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonnier-Voirin, A.; El Akremi, A.; Vandenberghe, C. A multilevel model of transformational leadership and adaptive performance and the moderating role of climate for innovation. Group. Organ. Manag. 2010, 35, 699–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 9781606238769. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Wu, Q. Introduction to structural equation modeling: Issues and practical considerations. Educ. Meas. 2007, 26, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Rhemtulla, M.; Gibson, K.; Schoemann, A.M. Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychol. Methods 2013, 18, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Finney, S.J.; DiStefano, C. Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course; Hancock, G.R., Mueller, R.O., Eds.; Information Age: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2013; pp. 439–492. ISBN 9781623962449. [Google Scholar]

- Urdan, T.C. Statistics in Plain English; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780415872911. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Aderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Bakker, A.B.; Bipp, T.; Verhagen, M.A.M.T. Individual job redesign: Job crafting interventions in healthcare. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 104, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T.; Gusy, B.; Wolter, C. The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work Stress 2019, 33, 76–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Organizational support (OS) | 3.188 | 0.493 | (0.842) | |||

| 2. Job crafting (JC) | 3.712 | 0.512 | 0.466 ** | (0.930) | ||

| 3. Work engagement (WE) | 3.298 | 0.628 | 0.483 ** | 0.786 ** | (0.953) | |

| 4. Adaptive performance (AP) | 3.309 | 0.403 | 0.303 ** | 0.778 ** | 0.618 ** | (0.886) |

| SB Scaled χ2 (df) | RMSEA | SRMR | TLI | CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Model (MA) | χ2 (129) = 408.092, p < 0.001 | 0.101 | 0.072 | 0.820 | 0.848 |

| Modified Measurement Model (MA-1) | χ2 (98) = 221.610, p < 0.001 | 0.077 | 0.060 | 0.909 | 0.925 |

| SB Scaled χ2 (df) | RMSEA | SRMR | TLI | CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Model (MB) | χ2 (99) = 225.443, p < 0.001 | 0.078 | 0.071 | 0.907 | 0.924 |

| Indirect Paths | ab | Bias-Corrected 95% CI * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| OS → WE → AP | 0.096 | 0.016 | 0.241 |

| OS → JC → WE → AP | 0.068 | 0.030 | 0.174 |

| OS → JC → WE → AP→ JC | 0.039 | 0.021 | 0.068 |

| OS → WE → AP → JC → WE | 0.030 | 0.009 | 0.057 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, Y.; Lim, D.H.; Kim, W.; Kang, H. Organizational Support and Adaptive Performance: The Revolving Structural Relationships between Job Crafting, Work Engagement, and Adaptive Performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124872

Park Y, Lim DH, Kim W, Kang H. Organizational Support and Adaptive Performance: The Revolving Structural Relationships between Job Crafting, Work Engagement, and Adaptive Performance. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124872

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Yoonhee, Doo Hun Lim, Woocheol Kim, and Hana Kang. 2020. "Organizational Support and Adaptive Performance: The Revolving Structural Relationships between Job Crafting, Work Engagement, and Adaptive Performance" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124872