Corporate Governance, Integrated Reporting and Environmental Disclosure: Evidence from the South African Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background: Corporate Governance Codes in South Africa and IR

- Applicability;

- Board composition (Chapter 2);

- Audit committees (Chapter 3);

- Risk management (Chapter 4);

- IT governance (Chapter 5);

- Internal audit (Chapter 7);

- Stakeholder inclusive model (Chapter 8);

- Integrated reporting (Chapter 9).

3. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses Development

4. Research Methodology: Data and Empirical Study Features

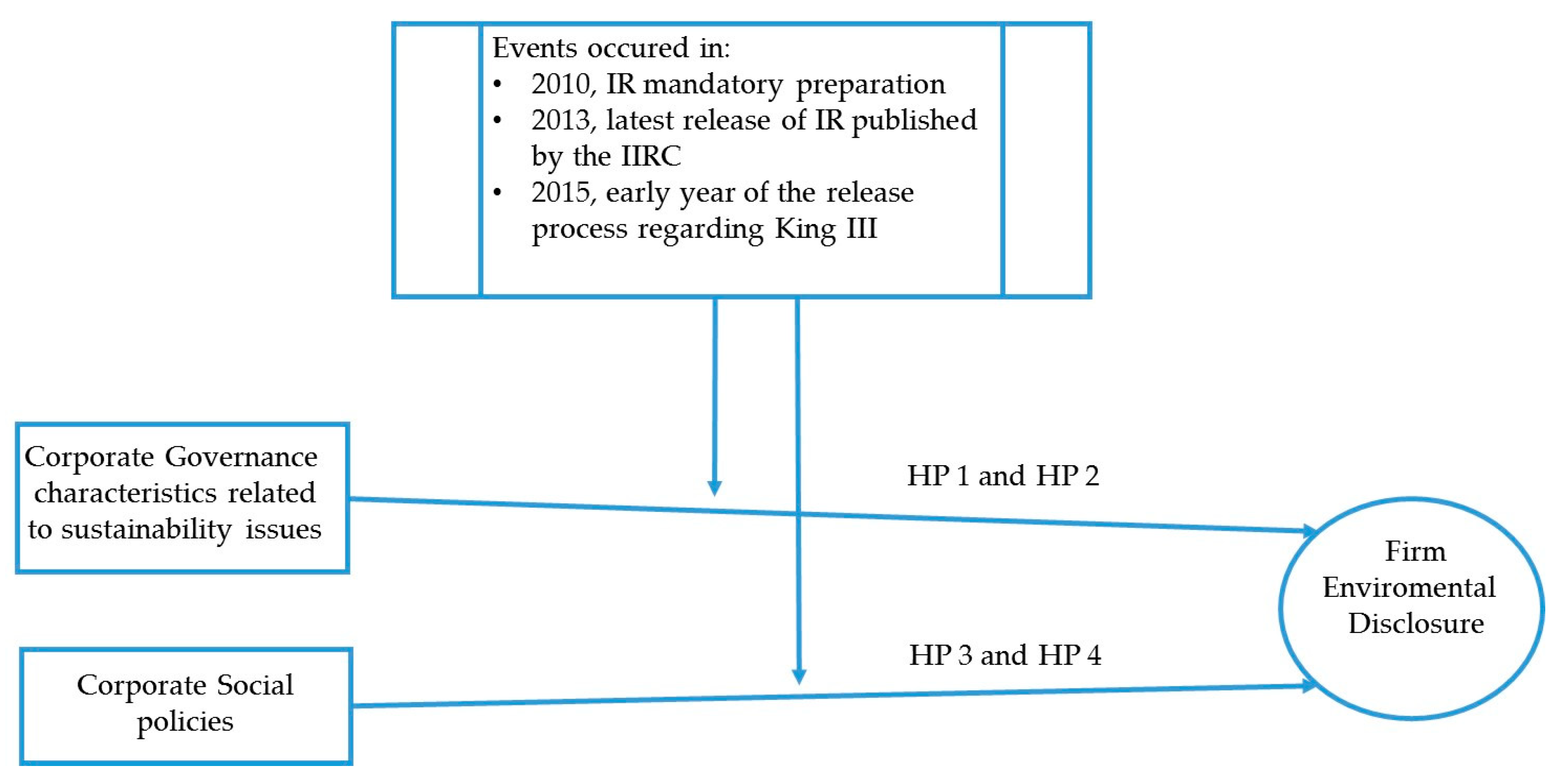

- 2010, as 1 March 2010 is the cut-off date from which JSE then required listed companies to prepare IR;

- 2013, the year when the IIRC published the latest release of the framework for IR;

- 2015, the earliest year of the release process regarding King III. Moreover, it is the latest year fully covered, given that afterwards, we gathered ESG data from April to September 2016.

- CG characteristics related to sustainability issues and firm environmental disclosure, and

- Corporate social policies and firm environmental disclosure.

5. Discussion of Findings

6. Discussion and Conclusions

- (a)

- It is able to extend the early findings by carrying out an empirical analysis on South Africa, which is the unique case of IR mandatory adoption in the world.

- (b)

- It can emphasize the crucial role played by the IR requirement and by the principles issued by King III to link social issues, such as health and safety and human rights policies, to the firm’s attitude to improve its environmental disclosure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eccles, R.G.; Kruz, M.P. One Report—Integrated Reporting for a Sustainable Society; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, R.G.; Krzus, M.P.; Ribot, S. The Integrated Reporting Movement, Meaning, Momentum, Motives and Materiality; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.W.; Yeo, G.H.H. The association between integrated reporting and firm valuation. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2016, 47, 1221–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C.; Venter, E.R.; Hsiao, P.K. Integrated reporting: Background, measurement issues, approaches and an agenda for future research. Account. Financ. 2017, 57, 937–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, C.R. The Corporate Psychopaths Theory of the Global Financial Crisis. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. The Sustainable Development Goals, Integrated Thinking and the Integrated Report; IIRC and ICAS: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-909883-41-3. Available online: https://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/SDGs-and-the-integrated-report_full17.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Adams, C.A.; Druckman, P.B.; Picot, R.C. Sustainable Development Goal Disclosure (SDGD) Recommendations; ACCA: London, UK; CA ANZ Group: Melbourne, Australia; ICAS: Edinburgh, UK; IFAC: New York, NY, USA; IIRC: London, UK; WBA: The Hawthorns, Birmingham, 2020; ISBN 978-1-909883-62-8. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, M.J.; Gray, R. W(h)ither ecology? The triple bottom line, the global reporting initiative, and corporate sustainability reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 11, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. The International Integrated Reporting Council: A call to action. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 27, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, B.; Al-Sultan, W. Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure in Kuwait. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2010, 7, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doni, F.; Corvino, A.; Bianchi Martini, S. King Codes on Corporate Governance and ESG performance. Evidence from FTSE/JSE All-Share Index. In Integrated Reporting. Antecedents and Perspectives for Organizations and Stakeholders; Idowu, S.O., Del Baldo, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carels, C.; Maroun, W.; Padia, N. Integrated reporting in the South African mining sector. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2013, 11, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.; Maroun, W. Integrated Reporting: The New Face of Social, Ethical and Environmental Reporting in South Africa? ACCA, Ed.; The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abeysekera, I. A template for integrated reporting. J. Intellect. Cap. 2013, 14, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doni, F.; Fortuna, F. Corporate Governance code in South Africa after the adoption of Integrated Reporting, Evidence from the mining industry. Int. Bus. Manag. 2018, 12, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Steyn, M. Organisational benefits and implementation challenges of mandatory integrated reporting: Perspectives of senior executives at South African listed companies. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2014, 5, 476–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Haji, A.; Anifowose, M. The trend of integrated reporting practice in South Africa: Ceremonial or substantive? Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 190–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias-Aceituno, J.V.; Rodriguez-Ariza, L.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.M. The Role of the Board in the Dissemination of Integrated Corporate Social Reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Xi Dai, T.M. Integrated thinking as an organizational cultural control? In Proceedings of the Critical Perspectives on Accounting Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 7–9 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, J.; Maroun, W. Integrated reporting in South Africa in 2012: Perspectives from South African institutional investors. Meditari Account. Res. 2015, 23, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Youmans, T. Materiality in Corporate Governance: The Statement of Significant Audiences and Materiality. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2016, 28, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Frias-Aceituno, J.V.; Rodriguez-Ariza, L.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.M. Explanatory Factors of Integrated Sustainability and Financial Reporting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Directors in Southern Africa, (IoDSA). King Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa (King IV Report). 2016. Available online: https://ecgi.global/sites/default/files/codes/documents/King_Report_On_Corporate_Governance_For_South_Africa_2016.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Setia, N.; Abhayawansa, S.; Joshi, M.; Huynh, A.V. Integrated reporting in South Africa: Some initial evidence. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2015, 6, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raemaekers, K.; Maroun, W.; Padia, N. Risk disclosures by South African listed companies post-King III. S. Afr. J. Account. Res. 2016, 30, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindley, T.; Buys, P. Integrated reporting compliance with the global reporting initiative framework: An analysis of the South African mining industry. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2012, 11, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensburg, R.; Botha, E. Integrated Reporting the silver bullet of financial communication? A stakeholder perspective from South Africa. Public Relat. Rev. 2014, 40, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doni, F.; Gasperini, A.; Pavone, P. Early adopters of integrated reporting. The case of the mining industry in South Africa. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 10, 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- IoD. King Code of Governance for South Africa 2009; Institute of Directors Southern Africa: Sandton, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.A.; Hill, W.Y.; Roberts, C.B. Corporate social reporting practices in Western Europe: Legitimating corporate behaviour? Br. Account. Rev. 1998, 30, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busco, C.; Frigo, M.L.; Riccaboni, A.; Quattrone, P. Integrated Reporting: Concepts and Cases That Redefine Corporate Accountability; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Integrated Reporting Council, IIRC. The International <IR> Framework; IIRC: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dumay, J.; Bernardi, C.; Guthrie, J.; Demartini, P. Integrated reporting: A structured literature review. Account. Forum 2016, 40, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhia, S. Exploring the Transition to Integrated Reporting Through a Practice Lens: An Australian Customer Owned Bank Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.I.; Coelho, A.M. Engaged in integrated reporting? Evidence across multiple organizations. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2018, 30, 398–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossouw, G.J.; Van Der Watt, A.; Malan Rossouw, D. Corporate Governance in South Africa. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 37, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakabadse, A.; Korac-Kakabadse, N. Corporate governance in South Africa: Evaluation of the King II Report (Draft). J. Chang. Manag. 2002, 2, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyereboah-Coleman, A. Corporate Governance and Shareholder Value Maximization: An African Perspective. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2007, 19, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beer, E.; Rensburg, R. Towards a theoretical framework for the governing of stakeholder relationships: A perspective from South Africa. J. Public Aff. 2011, 11, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ntim, C.G.; Opong, K.K.; Danbolt, J. The Relative Value Relevance of Shareholder versus Stakeholder Corporate Governance Disclosure Policy Reforms in South Africa. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2012, 20, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Lara, J.M.; García Osma, B.; Penalva, F. Accounting conservatism and corporate governance. Rev. Account. Stud. 2009, 14, 161–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borker, R.D. Accounting, Culture, and Emerging Economies: IFRS in the BRIC Countries. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2012, 10, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. King III Summary. Department of Professional Practice. 2009. Available online: https://www.saica.co.za/Portals/0/documents/KPMG%20King%20III%20Summary.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Maniora, J. Is Integrated Reporting Really the Superior Mechanism for the Integration of Ethics into the Core Business Model? An Empirical Analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 755–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C. Conceptualising the contemporary corporate value creation processes. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 906–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Garcìa, L.; Zorio-Grima, A.; Garcìa-Benau, M.A. Stakeholder Engagement, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Integrated Reporting: An Exploratory Study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder-Webb, L.; Cohen, J.R.; Nath, L.; Wood, D. The Supply of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures Among U.S. Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Green, W.; Conradie, P.; Konishi, N.; Romi, A. The International Integrated Reporting Framework: Key Issues and Future Research Opportunities. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2014, 25, 90–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghiemstra, R. Corporate Communication and Impression Management. New Perspectives Why Companies Engage in Corporate Social Reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 27, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melloni, G. Intellectual capital disclosure in integrated reporting: An impression management analysis. J. Intellect. Cap. 2015, 16, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInerney, C.; Johannsdottir, L. Lima Paris Action Agenda: Focus on Private Finance. Note from COP21. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trireksani, T.; Djajadikerta, H.G. Corporate Governance and Environmental Disclosure in the Indonesian Mining Industry. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2016, 10, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommadath, B.; Sarkar, R.; Rath, B. A Fuzzy Logic Based Approach to Assess Sustainable Development of the Mining and Minerals Sector. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Overell, M.B.; Chapple, L. Environmental reporting and its relation to corporate environmental performance. Abacus J. Account. Financ. Bus. Stud. 2011, 47, 27–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual’. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Venturelli, A.; Caputo, F. The “comply-or-explain” principle in directive 95/2014/EU. A rhetorical analysis of Italian PIEs. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, J.A.; Benedek, J.; Ivan, K. Measuring sustainable development goals at a local level: A case of a metropolitan area in Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, J.L.; Berrone, P.; Phan, P.H. Corporate governance and environmental performance: Is there really a link? Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 885–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcìa-Sànchez, I.; Rodriguez-Dominguez, L.; Frias-Aceituno, V. Board of Directors and Ethics Codes in Different Corporate Governance Systems. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 681–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, T.; Ziniel, C. Green governance? Local politics and ethical businesses in Great Britain. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waweru, N. Business ethics disclosure and corporate governance in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2020, 28, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Walsh, J.P. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.P.; Khanna, S. Corporate social responsibility, corporate governance and sustainability: Synergies and inter-relationships. Indian J. Corp. Gov. 2014, 7, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwagbara, U.; Ugwoji, C.A. Corporate Governance, CSR Reporting and Accountability: The Case of Nigeria. Econ. Insights Trends Chall. 2015, IV, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kolk, A.; Pinkse, J. The integration of corporate governance in corporate social responsibility disclosures. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, F.J.; Stoelhorst, J.W. The role of governance in corporate social responsibility: Lessons from Dutch finance. Bus. Soc. 2013, 52, 282–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Lee, S.P.; Devi, S.S. The Influence of Governance Structure and Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility Toward Sustainability Reporting Quality. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Keim, G.D.; Luce, R.A. Board Composition and Stakeholder Performance: Do Stakeholder Directors make a Difference? Bus. Soc. 2001, 40, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassinis, G.; Vafeas, N. Corporate boards and outside stakeholders as determinants of environmental litigation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallin, C.A.; Michelon, G. Board reputation attributes and corporate social performance: An empirical investigation of the US Best Corporate Citizens. Account. Bus. Res. 2011, 41, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt-Toth, E. Who should be on a board corporate social responsibility committee? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1926–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Parbonetti, A. The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. J. Manag. Gov. 2012, 16, 477–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagasio, V.; Cucari, N. Corporate governance and environmental social governance disclosure: A meta-analytical review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, B. The construction of a social account: A case study in an overseas aid agency. Account. Organ. Soc. 2005, 30, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Lorenzo, J.M.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.M. The Role of the Board of Directors in Disseminating Relevant Information on Greenhouse Gases. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 391–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.F.; Romi, A.M. Does the voluntary adoption of corporate governance mechanisms improve environmental risk disclosures? Evidence from greenhouse gas emission accounting. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 637–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupley, K.H.; Brown, D.; Marshall, R.S. Governance, media and the quality of environmental disclosure. J. Account. Public Policy 2012, 31, 610–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.P.; Priem, R.L.; Coombs, J.E.; Gilley, K.M. Do CEO stock options prevent or promote fraudulent financial reporting? Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Larraza-Kintana, M. Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Adm. Sci. Q. 2010, 55, 82–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IIRC; Black Sun. The Integrated Reporting Journey: The Inside Story. 2015. Available online: www.theiirc.org (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Ullah, M.; Muttakin, M.; Khan, A. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures in insurance companies. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2019, 27, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, G.; Konteos, G.; Sariannidis, N. Financial, governance and environmental determinants of corporate social responsible disclosure. Manag. Decis. 2014, 52, 1928–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; de Sousa-Filho, J.M. Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. Effects of corporate governance on the decision to voluntarily disclose corporate social responsibility reports: Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 5900–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Muttakin, M.B.; Siddiqui, J. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Rodrigues, L.L.; Craig, R. Corporate Governance Effects on Social Responsibility Disclosures. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2017, 11, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewpersadh, N.S. A theoretical and econometric evaluation of corporate governance and capital structure in JSE-listed companies. Corp. Gov. 2019, 19, 1063–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puni, A.; Anlesinya, A. Corporate governance mechanisms and firm performance in a developing country. Int. J. Law Manag. 2020, 62, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilincarslan, E.; Elmagrhi, M.H.; Li, Z. Impact of governance structures on environmental disclosures in the Middle East and Africa. Corp. Gov. 2020, 20, 739–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C.; Alexander, D. The institutionalisation of corporate social responsibility reporting. Br. Account. Rev. 2014, 46, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufflet, E.; Cruz, L.B.; Bres, L. An assessment of corporate social responsibility practices in the mining and oil and gas industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, H.; Kulkzycka, J.; Hausner, J.; Konski, N. Corporate Social Responsibility: Communication about social and environmental disclosure by large and small copper mining companies. Resour. Policy 2016, 49, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntim, C.G. Corporate governance, corporate health accounting, and firm value: The case of HIV/AIDS disclosures in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Account. 2016, 51, 155–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organization fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 46, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Governance for sustainability. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2006, 14, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soobaroyen, T.; Ntim, C.G. Social and environmental accounting as symbolic and substantive means of legitimation: The case of HIV/AIDS reporting in South Africa. Account. Forum 2013, 37, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Haque, S.; Roberts, R. Human Rights Performance Disclosure by Companies with Operations in High Risk Countries: Evidence from the Australian Minerals Sector. Aust. Account. Rev. 2017, 27, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, C.; Ngunjiri, F.W. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in South Africa: A Descriptive and Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2008, 45, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J.H. The Global Pact for the Environment: At the crossroads of human rights and the environment. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Law 2019, 28, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, J.M.; Yuthas, K. Corporate Social Performance, Stakeholder Orientation, and Organizational Moral Development. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 1213–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanwick, S.D.; Stanwick, P.A. Corporate social responsiveness: An empirical examination using the environmental disclosure index. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 1998, 8, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadeo, J.D.; Oogarah-Hanuman, V.; Soobaroyen, T.A. Longitudinal Study of Corporate Social Disclosures in a Developing Economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, N.; Sebastianelli, R. Transparency among S&P 500 companies: An analysis of ESG disclosure scores. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1660–1680. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, G.M. Common myths about business ethics: Perspectives from Hong Kong. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 1995, 4, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Foss, C. Business Ethics: Corporate Responses to Scandal. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2004, 7, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, M.S. Professional codes: Why, how, and with what impact? J. Bus. Ethics 1989, 8, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, B.J.; Cobbin, D.M.; Farrell, H.M. Can codes of ethics really produce consistent behaviours? J. Manag. Psychol. 2002, 17, 468–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, J.A.; Emerson, T.L.; Neubert, M. The effects of ethical codes on ethical perceptions of actions toward stakeholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, S.; Chong, G.; Isimoya, E. Disclosure of governance information by small and medium-sized Companies. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Eff. Board Perform. 2007, 7, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, H.; Smit, A.R. Factors influencing corporate governance disclosure of companies listed on the Alternative Exchange (AltX) in South Africa. South Afr. J. Account. Res. 2015, 29, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegrini, M.; Greco, G. Corporate boards, audit committees and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Italian listed companies. J. Manag. Gov. 2013, 17, 187–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Ye, C. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance: Empirical insights on neo-institutional framework from China. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2018, 15, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankara, J.; Lindberg, D.; Nowland, J. Are board governance characteristics associated with ethical corporate social responsibility disclosure? The case of the mandatory conflict minerals reporting requirement. J. Leadersh. Account. Ethics 2017, 14, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, M.A. Valuing Stakeholder Engagement and Sustainability Reporting. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2015, 18, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A. Theorising South Africa’s Corporate Governance. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 68, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tang, L.; Gallagher, C.C.; Bie, B. Corporate social responsibility communication through corporate websites a comparison of leading corporations in the United States and China. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2014, 52, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. Institutional drivers for corporate social responsibility in an emerging economy a mixed-method study of Chinese business executives. Bus. Soc. 2015, 1, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Upholding labour standards through corporate social responsibility policies in China. Glob. Soc. Policy 2015, 15, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or mis-specification. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, L.H.; Amato, C.H. The effects of firm size and industry on corporate giving. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Lavers, S. Corporate social and environmental reporting. A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.C.; Hung, M.; Wang, Y. The effect of mandatory CSR disclosure on firm profitability and social externalities: Evidence from China. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 65, 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, G.; Dippenaar, M.; Fourie, C.; Franken, D. Sharebased remuneration: Per-director disclosure practices of selected listed South African companies. J. Econ. Financ. Sci. 2019, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R.L.; Lewin, A.Y. Where are the theories for the “new” organizational forms? An editorial essay. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, i–vi. [Google Scholar]

- Aragon-Sanchez, A.; Barba-Aragon, I.; Sanz-Valle, R. Effects of training on business results. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2003, 14, 956–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, P.; Arenas, D. Do Employees Care About CSR Programs? A Typology of Employees According to their Attitudes. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Delobbe, N. Do Environmental CSR Initiatives Serve Organizations’ Legitimacy in the Oil Industry? Exploring Employees’ Reactions through Organizational Identification Theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Cai, Z. The effects of employee training on the relationship between environmental attitude and firms’ performance in sustainable development. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2995–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulouta, I.; Pitelis, C.N. Who Needs CSR? The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on National Competitiveness. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 119, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldrige, J.M. Introductory Econometrics. A Modern Approach; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, C.F.; Schaffer, M.E.; Stillman, S. Instrumental variables and GMM: Estimation and Testing. Stata J. 2003, 3, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, R.M.; Cooke, T.E. The Impact of Culture and Governance on Corporate Social Reporting. J. Account. Public Policy 2005, 24, 391–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Pike, R.; Haniffa, R. Intellectual capital disclosure and corporate governance structure in UK firms. Account. Bus. Res. 2008, 38, 137–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Date Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Neter, J.; Wasserman, W.; Kunter, M. Applied Linear Regression Models; Irwin: Homewood, MB, Canada, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P.; Clelland, I. Talking trash: Legitimacy, impression management, and unsystematic risk in the context of the natural environment. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P. From issues to actions: The importance of individual concerns and organizational values in responding to natural environmental issues. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J. Linking organizational and field-level analyses: The diffusion of corporate environmental practice. Organ. Environ. 2001, 14, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, H.; Schleper, M.C.; Blome, C. Conflict minerals and supply chain due diligence: An exploratory study of multi-tier supply chains. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 147, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, O.; Reinecke, J.; Spence, C.; Morrell, K. Signposts or weathervanes? The curious case of corporate social responsibility and conflict minerals. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 146, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.S. Integrated Reporting, Corporate Governance, and the Future of the Accounting Function. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- International Integrated Reporting Council, IIRC. Creating Value. Value to the Board. 2014. Available online: www.integratedreporting.org (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Stainbank, L.J. The nature and extent of non-financial disclosures in the South African mining industry. In Proceedings of the Conference Proceedings Faculty of Ljubljana 35th Annual Congress European Accounting Association EAA, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 9–11 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H.; Harjoto, M.A. Corporate Governance and Firm Value: The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattermann, C.; Fetscherin, M.; Alon, I.; Li, S.; Schneider, A.M. CSR communication intensity in Chinese and Indian multinational companies. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2009, 17, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: An enabling role for accounting research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A.; Picot, R.C.; Druckman, P.B. Recommendations for SDG Disclosures: A Consultation Paper; CA ANZ Group: Melbourne, Australia; ICAS: Edinburgh, UK; ACCA: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-0-6482276-5-6. [Google Scholar]

- Majumder, M.T.H.; Akter, A.; Li, X. Corporate governance and corporate social disclosures: A meta-analytical review. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2017, 25, 434–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.H.; Umphress, E.E. To Help My Supervisor: Identification, Moral Identity, and Unethical Pro-supervisor Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoegbu, G.N.; Odoemelam, N.; Okaforet, R.G. Corporate board characteristics and environmental disclosure quantity: Evidence from South Africa (integrated reporting) and Nigeria (traditional reporting). Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Mans-Kemp, N.; Erasmus, P.D. Assessing the business case for environmental, social and corporate governance practices in South Africa. South Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2019, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, D.; Gravas, E.; Stavropoulos, A. Company characteristics and environmental policy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Fowler, H.R.; Ellstrand, A.E.; Johnson, J.L. The role of board environmental committees in corporate environmental performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviers, S.; Krüger, J.; Venter, D.J.L. The relative importance of ethics, environmental, social and governance criteria. Afr. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 6, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, C.E. Elevating the Role of Divestment in Socially Responsible Investing. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 153, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Measure | Expected Sign | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | env_disc_score | This score measures the firm transparency pertinent to environmental information. Data sources are both annual and sustainability reports, press releases, as well as third-party research. It ranges from zero to 100. A firm can gain the maximum score as long as it discloses every data point gathered by Bloomberg. Data points cover several environmental scopes, such as carbon emissions, climate change effects, pollution, waste disposal, renewable energy, resource depletion, and so on. Moreover, specific weight is attributed to each data point on the basis of its relevance. For instance, the disclosure over greenhouse gas emissions has a higher weight than other types of environmental information. | |

| Independent variables | business_ethics_policy | This variable indicates whether the firm has established ethical guidelines and/or a compliance policy for its management/executive employees in the conduct of company business. | + |

| ceo_duality | This variable points out whether, in the corporate governance model, the positions of both CEO and Chairman are performed by the same member of the BDs. | + | |

| health_safety_policy | This variable highlights whether the company puts policies in place to safeguard the health of its employees. | + | |

| human_rights_policy | This variable indicates whether the company puts policies in place to prevent human rights abuses. | + | |

| Control variable | staff_csr_training_cost | This variable shows the annual total amount of expenditure allocated to staff training on CSR issues. | + |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| env_disc_score | 285 | 26.3610 | 14.3516 | 2.33 | 65.29 |

| business_ethics_policy | 307 | 0.9316 | 0.2528 | 0 | 1 |

| ceo_duality | 338 | 0.0030 | 0.0544 | 0 | 1 |

| health_safety_policy | 306 | 0.9542 | 0.2093 | 0 | 1 |

| human_rights_policy | 307 | 0.5277 | 0.5000 | 0 | 1 |

| staff_csr_training_cost | 197 | 134,000,000 | 262,000,000 | 2935 | 2,300,000,000 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. business_ethics_policy | 1 (N = 307) | ||||

| 2. ceo_duality | 0.0156 (N = 304) | 1 (N = 338) | |||

| 3. health_safety_policy | 0.3736 * (N = 306) | 0.0127 (N = 303) | 1 (N = 306) | ||

| 4. human_rights_policy | 0.1313 * (N = 307) | 0.0545 (N = 304) | 0.1994 *** (N = 306) | 1 (N = 307) | |

| 5. staff_csr_training | −0.0204 (N = 197) | 0.0241 (N = 194) | −0.0569 (N = 196) | 0.1215 (N = 197) | 1 (N = 197) |

| Variable Dependent: env_disc_score | Expected Sign | Beta Coefficients | Standard Errors | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| business_ethics_policy | + | 15.4195 * | 6.1361 | 2.51 |

| ceo_duality | + | 3.6502 | 7.9892 | 0.46 |

| health_safety_policy | + | 14.8508 ** | 5.0165 | 2.96 |

| human_rights_policy | + | 4.5284 * | 2.2157 | 2.04 |

| staff_csr_training_cost | + | 2.1800 | 3.2200 | 0.68 |

| No of Observations | 188 | |||

| R2 within | 0.232 | |||

| F-statistic | 5.98 *** | |||

| Hausman Test | 10.10 * |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corvino, A.; Doni, F.; Bianchi Martini, S. Corporate Governance, Integrated Reporting and Environmental Disclosure: Evidence from the South African Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124820

Corvino A, Doni F, Bianchi Martini S. Corporate Governance, Integrated Reporting and Environmental Disclosure: Evidence from the South African Context. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124820

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorvino, Antonio, Federica Doni, and Silvio Bianchi Martini. 2020. "Corporate Governance, Integrated Reporting and Environmental Disclosure: Evidence from the South African Context" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124820

APA StyleCorvino, A., Doni, F., & Bianchi Martini, S. (2020). Corporate Governance, Integrated Reporting and Environmental Disclosure: Evidence from the South African Context. Sustainability, 12(12), 4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124820