Exploring Corporate Social Responsibility under the Background of Sustainable Development Goals: A Proposal to Corporate Volunteering

Abstract

1. Introduction

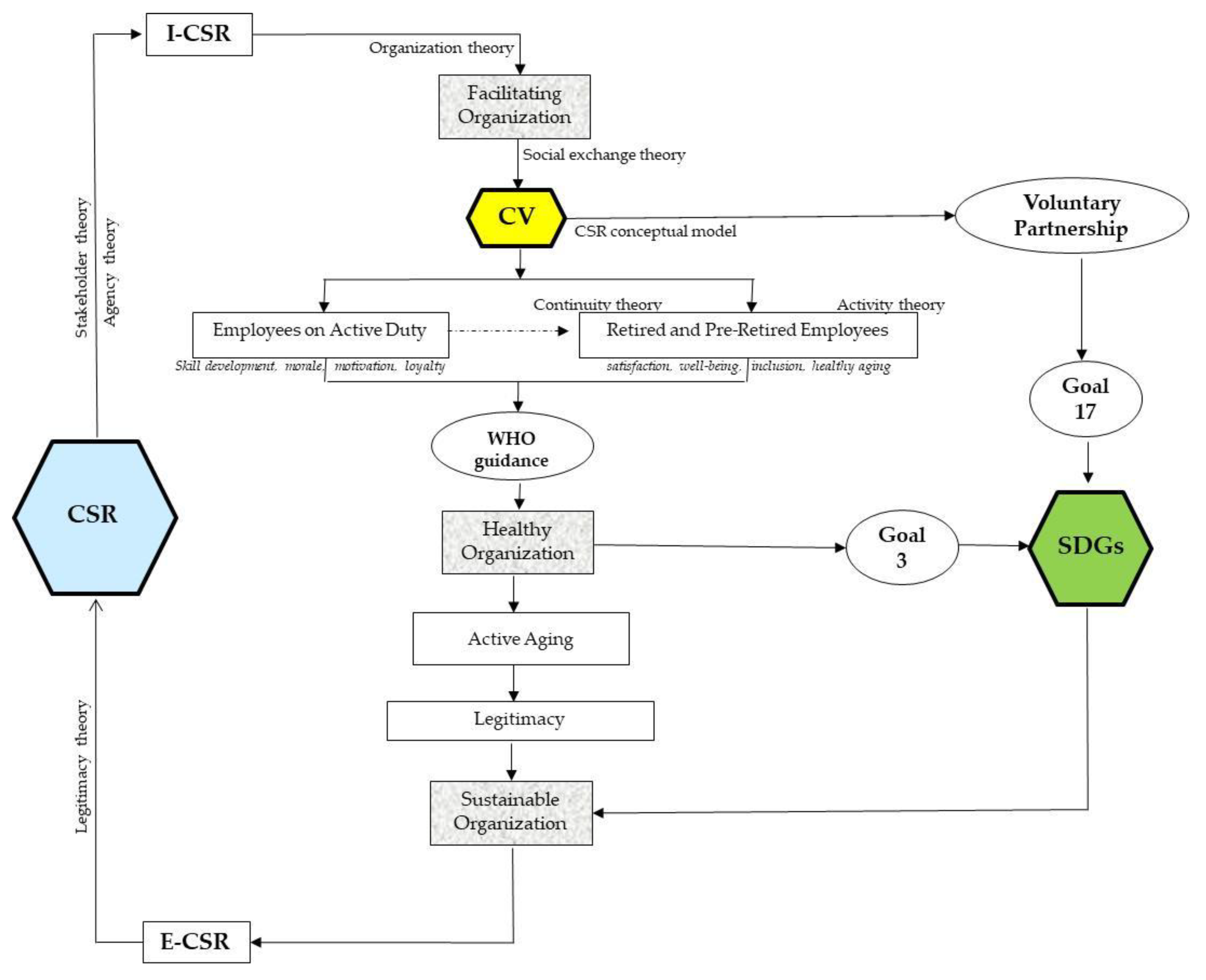

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Role of Business over the Sustainable Development Goals Processes

2.2. Theoretical Approaches on Corporate Volunteering

2.3. Retirement Challenges and Opportunities in Relation to Corporate Volunteering

2.4. Corporate Volunteering in Strengthening Corporate Social Responsibility

2.5. Benefits from Corporate Volunteering to Retiree Workers

3. Research Methodology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- United Nations. The Road to Dignity by 2030: Ending Poverty, Transforming All Lives and Protecting the Planet. Synthesis Report of the Secretary-General on the Post-2015 Agenda; 2014. New York. 2014. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/69/700&Lang=E (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Moore, H. Global prosperity and sustainable development goals. J. Int. Dev. 2015, 27, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.; Lucci, P. Universality and ambition in the post-2015 development agenda: A comparison of global and national targets. J. Int. Dev. 2015, 27, 752–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual’. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, H. Volunteers within an organizational context-one term is not enough. J. Bus. Econ. 2013, 4, 895–904. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Political declaration and Madrid international plan of action on ageing. In Proceedings of the Second World Assembly on Ageing, Madrid, Spain, 8–12 April 2002; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/events/pastevents/pdfs/Madrid_plan.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- United Nations. Resolution 46/91. In Implementing of the International Plan of Action on Ageing and Related Activities; Forty-sixth Session; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/olderpersons.aspx (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Cosenza, J.P.; Gil, M.I.S.; Alegría, A.I.Z. Corporate volunteering: A tool for promoting a strategy for internal corporate social responsibility integrating retirees. Revista Kairós Gerontologia 2018, 21, 161–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2018. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2018/TheSustainableDevelopmentGoalsReport2018-EN.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019: Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgindex.org/reports/sustainable-development-report-2019/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Hopkins, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and International Development: Is Business the Solution? Earthscan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blowfield, M. Business and development: Making sense of business as a development agent. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2012, 12, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorti, B.; Macmillan, G.; Siesfeld, T. Growth for Good or Good for Growth? How Sustainable and Inclusive Activities are Changing Business and Why Companies Aren’t Changing Enough; Citi Foundation, Fletcher School, Monitor Institute, 2014; Available online: https://www.citigroup.com/citi/foundation/pdf/1221365_Citi_Foundation_Sustainable_Inclusive_Business_Study_Web.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Luke, T. Corporate social responsibility: An uneasy merger of sustainability and development. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 21, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, J. Beyond the millenium development goals: A southern perspective on a global new deal. J. Int. Dev. 2015, 27, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remacha, M. Empresa y Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible; Cuadernos de la Cátedra CaixaBank de Responsabilidad Social Corporativa-IESE: Bacelona, Spain, 2017; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, S.A. Educação, Trabalho Voluntário e Responsabilidade Social da Empresa: “Amigos da Escolar” e Outras Formas de Participação. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Sao Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bareli, P.; Lima, A.J.F.d.S. A importância social do desenvolvimento do trabalho voluntário. Revista Ciências Gerenciais 2010, 14, 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Saz-Gil, M.I.; Zardoya-Alegría, A.I. Gestión del voluntariado corporativo en las organizaciones No lucrativas. Rev. Esp. Terc. Sect. 2014, 28, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Atchley, R.C. Continuity and Adaptation in Aging: Creating Positive Experiences; The John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; Hassay, D. Intra-organizational volunteerism: Good soldiers, good deeds and good politics. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 64, 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, D.Z.; Runte, M.S.; Easwaramoorthy, M.; Barr, C. Company support for employee volunteering: A national survey of companies in Canada. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 85, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organization; The Macmillan Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, A.G. Factores explicativos de la práctica de voluntariado corporativo en España. Rev. Int. Organ. 2013, 11, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiman, S. Agency research in managerial accounting: A survey. J. Account. Lit. 1982, 1, 154–213. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; ME Sharpe: White Plains, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strat. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.G.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.S.; Corchuelo Martínez-Azúa, M.B.C.; Guerra Guerra, A.G. Diagnóstico del voluntariado corporativo en la empresa española. Rev. Estud. Empres Segunda Época 2010, 2, 54–80. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambe, C.J.; Wittmann, C.M.; Spekman, R.E. Social exchange theory and research on business-to-business relational exchange. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 2001, 8, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, J.E.; Park, K.W.; Glomb, T.M. Employer-supported volunteering benefits: Gift exchange among employers, employees, and volunteer organizations. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Havighurst, R.J.; Neugarten, B.; Tobin, S.S. Disengagement, personality and life satisfaction in the later years. In Age with a Future; Hansen, P., Ed.; Munksgoard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1963; pp. 419–425. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, A.R.; Kahn, R.L.; Morgan, J.N.; Jackson, J.S.; Antonucci, T.C. Age differences in productive activities. J. Gerontol. 1989, 44, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchley, R.C. Continuity theory and the evolution of activity in later adulthood. In Activity and Aging: Staying Involved in Later Life; Kelly, J.R., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- European Network for Workplace Health Promotion (ENWHP) Luxembourg Declaration on Workplace Health Promotion in the European Union. Available online: https://www.enwhp.org/resources/toolip/doc/2018/05/04/luxembourg_declaration.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage. The World Health Report 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/whr/2010/en/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Gauthier, A.H.; Smeeding, T.M. Time use at older ages: Cross-national differences. Res. Aging 2003, 25, 247–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.K. Role Transitions in Later Life; Brooks/Cole Pub. Co.: Monterey, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- King, R.R.; Fluke, J. Volunteers: America’s Hidden Resource; University Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J. Employment and volunteering roles for the elderly: Characteristics, attributions, and strategies. J. Leis. Res. 1989, 21, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoh, M.-C.; Herzog, A.R. Individual consequences of volunteer and paid work in old age: Health and mortality. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Pensions at a Glance: OECD and G20 Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/b6d3dcfc-en (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Calero, M.; García-Berben, T.; Gálvez, M.; Toral, I.; Bailón, R. Appraisal of a self help program for aged people: Volunteer personnel profile. Psychosoc. Interv. 1996, 5, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, D.P.; Cutler, D.; Rowe, J.W.; Michaud, P.-C.; Sullivan, J.; Peneva, D.; Olshansky, S.J. Substantial health and economic returns from delayed aging may warrant a new focus for medical research. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 1698–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baert, S.; Norga, J.; Thuy, Y.; Van Hecke, M. Getting grey hairs in the labour market. An alternative experiment on age discrimination. J. Econ. Psychol. 2016, 57, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höpflinger, F. Third age and fourth age in ageing societies—Divergent social and ethical discourses. In Planning Later Life Bioethics and Public Health in Ageing Societies; Schweda, M., Pfaller, L., Brauer, K., Adloff, F., Schicktanz, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Volunteering in the United States, 2015. U.S. Department of Labor. 2016. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/volun.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Agulló-Tomás, M.S.; Agulló-Tomás, E.A.; Rodríguez-Suárez, J.R. Voluntariado para Mayores: Ejemplo de Envejecimiento Participativo y Satisfactorio. Rev. Interuniv. Form Profr. 2002, 45, 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Walker Information. The Walker Loyalty Report: Volunteerism, Philanthropy, and U.S. Employees. National Employee Loyalty Study. 2003. Available online: http://www.thevolunteercenter.net/docs/RES_EVP_WalkerLoyaltyReportUS_2003.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Gonyea, J.; Googins, B. Expanding the boundaries of corporate volunteerism: Tapping the skills, talent, and energy of retirees. Generations 2006, 30, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Guterbock, T.M.; Fries, J.C. Maintaining America’s Social Fabric: The AARP Survey of Civic Involvement; American Association of Retired Persons: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Curto Grau, M.C. La Responsabilidad Social Interna de las Empresas; IESE Business School: Barcelona, Spain, 2012; Available online: https://media.iese.edu/research/pdfs/ESTUDIO-318.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Guerraaz Díaz, E. Falta Integrar a Jubilados en los Programas Corporativos de Voluntariado. ¿Es más Conveniente Hacerse Voluntario una Vez Jubilado o Iniciar Durante la Vida Activa? 2016. Available online: http://www.expoknews.com/falta-integrar-a-jubilados-en-los-programas-corporativos-de-voluntariado/ (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Topa, G.; Valero, E. Preparing for retirement: How self-efficacy and resource threats contribute to retirees’ satisfaction, depression, and losses. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 811–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saz-Gil, I.; Gil-Lacruz, A.I.; Gil-Lacruz, M. Happiness and social capital: European senior citizen volunteers. Sociológia-Slovak Sociol. Rev. 2019, 51, 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M. Giving time, time after time: Work design and sustained employee participation in corporate volunteering. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 589–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, J.; Dury, S. Reasons for not volunteering: Overcoming boundaries to attract volunteers. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 726–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C.; Baker, P.L.; Dowell, D. Getting into the ‘Giving Habit’: The dynamics of volunteering in the UK. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2019, 30, 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila, M.; Díaz-Morales, J. Voluntariado y Tercera Edad [Volunteerism and Elderly]. An. Psicol. 2009, 25, 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri, P.; Mencin, A.; Jiang, K. Win-win-win: The influence of company-sponsored volunteerism programs on employees, NGOs, and business units. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 825–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Piderit, S.K. How does doing good matter? J. Corp. Citizsh. 2009, 2009, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briseño García, A.; Lavín Verástegui, J.; García Fernández, F. Exploratory analysis of corporate social responsibility and its dichotomy in the business‘s social and environmental activities. Contad. Adm. 2011, 233, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hambach, E. Volunteering Infrastructure in Europe; European Volunteer Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boris, E. Study on Nonprofit and Philanthropic Infrastructure; Nonprofit Quarterly: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Krasnopolskaya, I.; Roza, L.; Meijs, L. The relationship between corporate volunteering and employee civic engagement outside the workplace in Russia. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2015, 27, 640–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cycyota, C.S.; Ferrante, C.J.; Schroeder, J.M. Corporate social responsibility and employee volunteerism: What do the best companies do? Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waikayi, L.; Fearon, C.; Morris, L.; McLaughlin, H. Volunteer management: An exploratory case study within the British Red Cross. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantos, G.P. The boundaries of strategic corporate social responsibility. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 595–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, C.; Baetz, M.C.; Pancer, S.M. Leveraging human capital through an employee volunteer program: The case of Ford Motor Company of Canada. J. Intellect. Cap. 2009, 10, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Poyatos, J.; Bosioc, D.; Civico, G.; Khan, K.; Loro, S. Employee Volunteering and Employee Volunteering in Humanitarian Aid in Europe; European Volunteer Centre, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, A.; Pfarrer, M.D.; Little, L.M. A theory of collective empathy in corporate philanthropy decisions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreesbach-Bundy, S.; Scheck, B. Corporate volunteering: A bibliometric analysis from 1990 to 2015. Bus. Ethics 2017, 26, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, A. Voluntariado Corporativo para el desarrollo: Una Multiherramienta Estratégica. In Voluntariado Corporativo para el Desarrollo: Una herramienta estratégica para integrar empresa y empleados en la lucha contra la pobreza; Fundación CODESPA: Madrid, Spain, 2012; pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rodell, J.B.; Booth, J.E.; Lynch, J.W.; Zipay, K.P. Corporate volunteering climate: Mobilizing employee passion for societal causes and inspiring future charitable action. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1662–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Hernandez, M.I.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D. Approaching corporate volunteering in Spain. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2013, 13, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, R.W. Corporate Culture’s Influence on Employee Charitable Giving and Volunteering. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K. La Gran Carpa: Voluntariado Corporativo en la Era Global; Editorial Ariel: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. Fundación Seres. SERES, Valor Social 2018 V Informe del Impacto Social de las Empresas. 2018. Available online: https://www.fundacionseres.org/Repositorio%20Archivos/Informes/20190118_V%20Impacto%20social%20empresas%20DEF.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Setó-Pamies, D.; Papaoikonomou, E. Sustainable development goals: A powerful framework for embedding ethics, CSR, and sustainability in management education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grueso-Hinestroza, M.; González-Rodríguez, J.; Rey-Sarmiento, C. Valores de la cultura organizacional y su relación con el engagement de los empleados: Estudio exploratorio en una organización de salud. Investig. Pensam. Crít. 2014, 2, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wilson, M.G.; DeJoy, D.M.; Vandenberg, R.; Richardson, H.A.; McGrath, A.L. Work characteristics and employee health and well-being: Test of a model of healthy work organization. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 565–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sial, M.S.; Tran, D.; Alhaddad, W.; Hwang, J.; Thu, P.A. Are socially responsible companies really ethical? The moderating role of state-owned enterprises: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, E.A.; Marks, N.F. Formal volunteering as a protective factor for older adults’ psychological well-being. J. Gerontol. Ser. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2004, 59, S258–S264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musick, M.A.; Wilson, J. Volunteering and depression: The role of psychological and social resources in different age groups. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, J.; Paynter, J.; Petriwskyj, A. Volunteering as a productive aging activity: Incentives and barriers to volunteering by Australian seniors. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2007, 26, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J. Volunteer to work (V2W) scheme. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2014, 18, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, M.; Omari, M. Dignity and respect: Important in volunteer settings too! Equal. Divers Incl. Int. J. 2015, 34, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utting, P. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals through Social and Solidarity Economy: Incremental versus Transformative Change. Paper Prepared for the United Nations Task Force for Social and Solidarity Economy. 2018. Available online: http://unsse.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/WorkingPaper1_PeterUtting.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2020).

- Pérez, M.J.; Loro, S. Responsabilidad Social Corporativa Global y Voluntariado Corporativo para el Desarrollo Oportunidades para la Empresa, Oportunidades para las Personas. In Voluntariado Corporativo Para el Desarrollo: Una Herramienta Estratégica Para Integrar Empresa y Empleados en la Lucha Contra la Pobreza; Fundación CODESPA: Madrid, Spain, 2012; pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, S. Voluntariado Corporativo para el Desarrollo como Herramienta para las Areas de Gestión de Recursos Humanos Fomento de Valores y Desarrollo de Habilidades. In Voluntariado Corporativo Para el Desarrollo: Una Herramienta Estratégica Para Integrar Empresa y Empleados en la Lucha Contra la Pobreza; Fundación CODESPA: Madrid, Spain, 2012; pp. 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- El Akremi, A.; Gond, J.-P.; Swaen, V.; De Roeck, K.; Igalens, J. How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. J. Manag. 2015, 44, 619–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werther, W.B., Jr.; Chandler, D. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Stakeholders in a Global Environment; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Española de Contabilidad y Administración de Empresas (AECA). Responsabilidad Social Corporativa Interna. Delimitación Conceptual e Información; Documentos AECA, Serie Responsabilidad Social Corporative: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gond, J.P.; Igalens, J.; Swaen, V.; El Akremi, A. The human resources contribution to responsible leadership: An exploration of the CSR–HR interface. In Responsible Leadership; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B.A. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, G.; Cnaan, R.A.; Boehm, A. Religious attendance and volunteering: Testing national culture as a boundary condition. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2017, 56, 577–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Quadras, C. Voluntariado corporativo. In La Aplicación de la Responsabilidad Social a la Gestión de Personas; Media Responsable: Barcelona, Spain, 2008; pp. 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Verra, S.E.; Benzerga, A.; Jiao, B.; Ruggeri, K. Health promotion at work: A comparison of policy and practice across Europe. Saf. Health Work. 2018, 10, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, J. WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model: Background and Supporting Literature and Practices; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://www.who.int/occupational_health/healthy_workplace_framework.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- WHO. Healthy Workplaces: A WHO Global Model for Action. 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/occupational_health/healthy_workplaces/en/ (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Thomas, H. ¿Hay empresas saludables? Tres maneras de responder a esta pregunta. Oikonomics Rev. Econ. Empresa Soc. 2017, 8, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Lacruz, A.I.; Gil-Lacruz, M.; Saz-Gil, M. Socially active aging and self-reported health: Building a sustainable solidarity ecosystem. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Global Plan of Action on Workers’ Health (2008–2017): Baseline for Implementation [Global Country Survey 2008/2009 Executive Summary and Survey Findings]. 2013. Available online: https://www.who.int/occupational_health/who_workers_health_web.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Buhmann, K.; Jonsson, J.; Fisker, M. Do no harm and do more good too: Connecting the SDGs with business and human rights and political CSR theory. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 19, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K. Reporting on the Sustainable Development Goals—Early Evidence from Europe. 2019. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3411017 (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- DKW Informe Corporativo Integrado 2018. DKV Seguros. Nos Esforzamos por un Mundo más Saludable. Available online: https://issuu.com/segurosdkv/docs/informe_corporativo_2018 (accessed on 30 May 2020).

- Red Española del Pacto Mundial Las Empresas Españolas Ante la Agenda 2030 [Análisis, Propuestas, Alianzas y Buenas Prácticas]. 2018. Available online: https://www.pactomundial.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Las-empresas-espa%C3%B1olas-ante-la-Agenda-2030_def_p.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2020).

| Theory | Subject | Support to CV | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legitimacy | Institutions represent the structuring rules of a business game directed to actions towards socially desired values, represented by the establishment and dissemination of standard actions and behaviors that incentivize those competences implicit in power structures and mental models, to achieve business legitimacy. | The CV program does not only provide financial help but also compliance with a set of general rules of behavior to achieve social legitimacy, converging with the solidarity mission that society entrusts the company with. | [22,23,24] |

| Organization | The company is identified as an organization open to society under a polyhedral reality divided into various dimensions. All these dimensions allow an analysis from different magnitudes, including its environment, but with an overall vision and also, giving the human factor the leading role in the organization. | The CV activities are conceived from the perspective that the company is open to society and puts the human factor at the center of actions. | [25,26] |

| Agency | The existence of information and asymmetric interests in the company justifies the need to carry out studies aimed at minimizing the agency costs existing in the company. | The CV program reduces company’ agency costs by increasing its social standing. | [26,27] |

| Resources and Capabilities | The intrasectorial differences due to the resources and capacities of each company generate different results which open the door to the design of strategies to generate competitive advantages by contributing to the development of capabilities. | CV allows approaching strategies that will lead to better performances, especially in relation to the company’s employees, since it generates competitive advantages by contributing to the development of their capacities. | [28,29,30] |

| Stakeholders | Companies need to have good relationships with all stakeholders, owing to meet the demands of the different interest groups linked to the organization, especially the needs of employees and society. | Companies should meet the demands of the employees and society since they are the ultimate beneficiaries of the effects of the practiced CV. | [31,32] |

| Social Exchange | Relations are understood as a social behavior that may result in economic and social outcomes in a company that is socially responsible when it takes social exchange into account in its planning, objectives and strategies directed to the economic, social and environmental aspects. | CV aims for companies to channel their social responsibility actions through non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or non-profit organizations (NPOs), benefiting from getting volunteers from the companies. | [33,34] |

| Corporate social responsibility (CSR) conceptual model | Social objectives integrate with the organizational priorities, embedding CSR in the strategic analysis of the company, so that the organization responds to social and environmental problems by taking actions that improve its value chain or competitiveness. | CV activity is assigned as strategic actions to increase competitive value in its social and environmental performance. | [35,36] |

| Activity | The more active the senior aging process is, and the more social activities are carried out by them, the greater satisfaction they will obtain in their life will be. | The CV program is based on the premise that the substitution of activities helps maintaining subjective and moral well-being. | [37,38] |

| Continuity | Senior past experiences are connected with their activities, behaviors, personalities and relationships in old age. | CV activities aim to preserve people’s well-being throughout their life, maintaining patterns of behavior previously established, especially in transitions such as retirement. | [21,39] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saz-Gil, M.I.; Cosenza, J.P.; Zardoya-Alegría, A.; Gil-Lacruz, A.I. Exploring Corporate Social Responsibility under the Background of Sustainable Development Goals: A Proposal to Corporate Volunteering. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4811. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124811

Saz-Gil MI, Cosenza JP, Zardoya-Alegría A, Gil-Lacruz AI. Exploring Corporate Social Responsibility under the Background of Sustainable Development Goals: A Proposal to Corporate Volunteering. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4811. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124811

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaz-Gil, María Isabel, José Paulo Cosenza, Anabel Zardoya-Alegría, and Ana I. Gil-Lacruz. 2020. "Exploring Corporate Social Responsibility under the Background of Sustainable Development Goals: A Proposal to Corporate Volunteering" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4811. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124811

APA StyleSaz-Gil, M. I., Cosenza, J. P., Zardoya-Alegría, A., & Gil-Lacruz, A. I. (2020). Exploring Corporate Social Responsibility under the Background of Sustainable Development Goals: A Proposal to Corporate Volunteering. Sustainability, 12(12), 4811. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124811