1. Introduction

Despite the rising urgency of societal challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, social inequality, and economic instability, status quo oriented socio-economic development continues largely unaltered and incremental policy changes predominate [

1,

2,

3,

4]. While recent growth in grassroots movements are becoming harder to ignore, calls for more fundamental change can increasingly be heard also from mainstream institutions like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [

5], and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) [

6,

7]. The potential of social innovation to challenge and transform established institutions more fundamentally has gained attention from policy actors [

8]. Yet, recent research on the dynamics of transformative social innovation [

9] points to the ambiguous character of innovation in terms of its potential to both reproduce and transform the status quo [

10,

11,

12]. While existing research focuses mostly on describing dynamics of how social innovation can develop, spread, and interact with established institutions [

13], little research exists about ways to identify and assess transformative impact, as well as the capacities required for social innovation efforts to become transformative.

Building on the recent Transformative Social Innovation (TSI) theory [

9,

14,

15], we previously developed a conceptual framework and research agenda [

16] for better understanding transformative impact and transformative capacity in a way that is meaningful in practice. In our conceptual framework we articulated three institutional dimensions as categories for defining transformative impact and capacity: depth, width, and length. This builds on similar typologies [

13] of how social innovations can grow, diffuse, or scale, while operationalizing the elements in more concrete and practice-oriented terms. For each of these three dimensions, we described constituting elements of transformative impact as well as the capacities needed for social innovators to realize such impact. In the remainder of this article we refer to this as the 3D framework (summarized in the next section). The 3D framework [

16] has so far been rather hypothetical, as an attempt to reformulate key issues in TSI theory in practice relevant terms. Hence, the intention of this article is to further develop this framework in ways that make it more analytically rigorous, empirically-based, and connected to everyday reality and needs of practitioners.

The purpose of this article is two-fold: firstly, to apply the 3D framework in different case contexts, so as to identify empirical examples that substantiate the framework elements and to refine these elements where needed. This makes the 3D framework more understandable and useful in practice. That is, concrete examples help to understand what the framework elements mean concretely, which issues are important to consider, and why. This can guide operationalization of the 3D framework for use by practitioners and researchers interested in studying and supporting diverse kinds of social innovation actors. Performing a rigorous, in-depth assessment or comparative analysis of the cases is considered beyond the scope of this article. Secondly, we aim to test the 3D framework in practice, in terms of its recognizability (how does it resonate?) and usefulness for practitioners (is it practically meaningful?). This article therefore addresses the following two research questions:

RQ1: How can the 3D framework serve to identify and assess transformative impact and the required transformative capacity in empirical cases of social innovation?

RQ2: To what extent and in which way is the 3D framework perceived as recognizable and useful by practitioners?

Different ways of applying the 3D framework are explored to test how it could be made useful in practice. We see this as an important step towards operationalizing the 3D framework in the form of a practice tool to support efforts of capacity building and impact achievement. Some possible applications of the 3D framework include using it for impact assessment, strategy development, design of interventions, internal reflection, monitoring, and evaluation.

The article is structured in the following way: in

Section 2 we summarize the 3D framework [

16] and how it builds on related literature. In

Section 3 we describe the methodology and empirical cases that serve for applying and testing the framework.

Section 4 presents the results of this study, which consist of the substantiating examples and refinements of the 3D framework, as well as practitioner responses about how the framework was perceived as recognizable and useful in practice. In

Section 5 we discuss our findings in light of our research questions and their significance for theory and practice, reflect on the limitations of this study, and provide recommendations for future research.

2. Three Dimensions of Transformative Change, Impact, and Capacity

Transformative change is a conceptually contested term, defined from many theoretical lenses [

17]. Different aspects of transformative change are pertinent to mention (though we do not address these in detail): what it is (not), why and when it is needed, how it can come about, and how to know if it occurred. In this section we summarize the 3D framework of transformative impact and capacity and briefly discuss how it connects to these considerations and related literature (for more details, see our original explanation of the 3D framework [

16]).

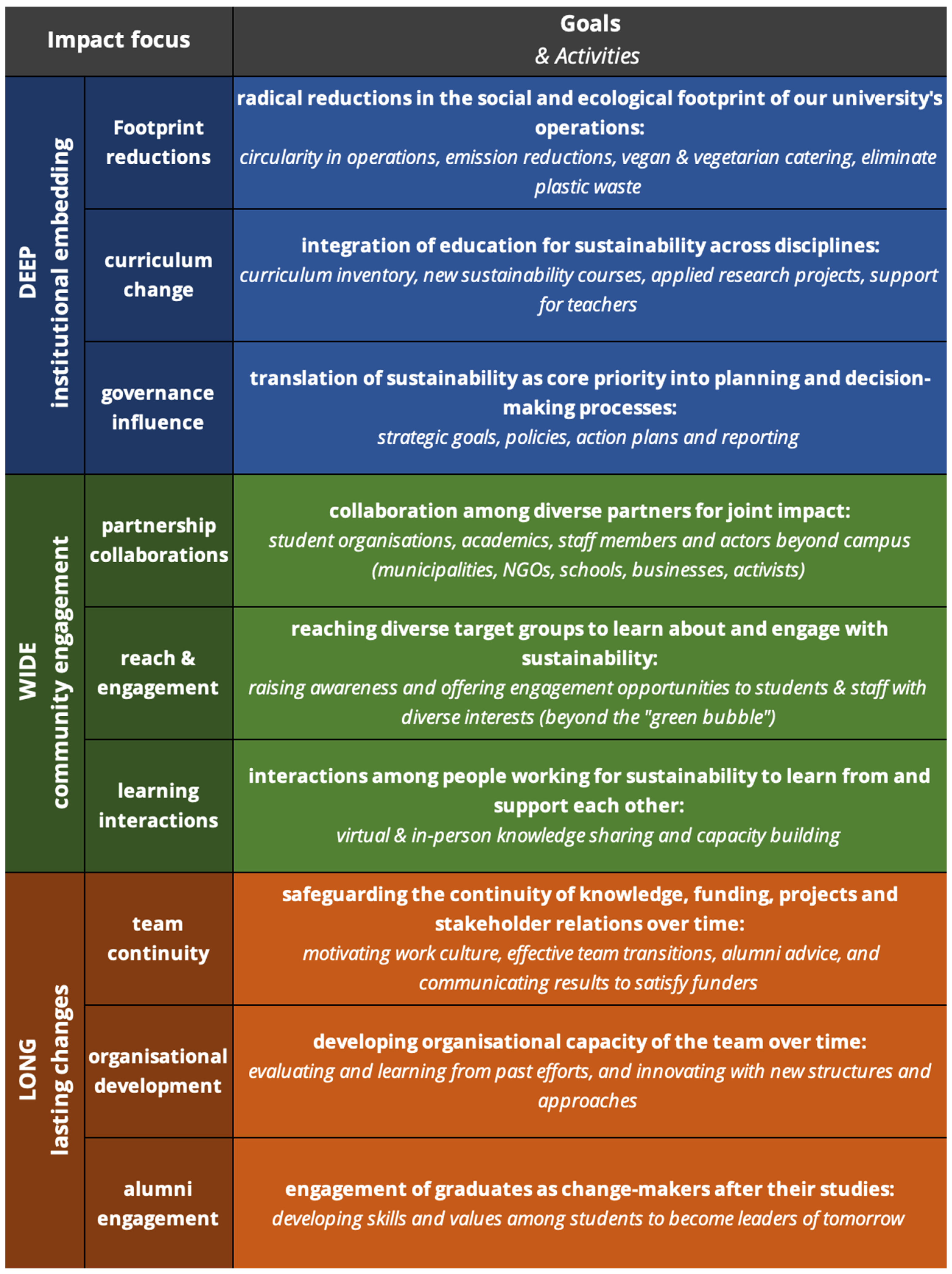

The 3D framework [

16] articulates three dimensions of institutional change as a way to make more specific the types and degrees of transformative impact and the capacities required to realize such impact. This was developed in response to the need for 1. a conceptual language for describing degrees of depth, diffusion and stability in the developing theory of Transformative Social Innovation (TSI) that is “recognizable and useful in policy and practice” (p. 169) and 2. empowering heuristics and theories of change to inform strategies of practitioners (p. 20) [

18]. From an institutional perspective, TSI theory proposes that the unique characteristic of transformative change, as opposed to non-transformative change, is that it involves “challenging, altering, or replacing dominant institutions” [

9]. However, this is still rather imprecise as to how fundamentally, at which scale, and how persistently dominant institutions are being challenged, altered, or replaced. We proposed [

16] that the notion of “degrees of institutionalization” [

18] (p. 18) along depth, width, and length dimensions can allow for a more precise conceptualization of transformative change, in a way that can be recognizable and useful in practice.

The three dimensions can be used to describe how deeply, widely, and persistently institutionalized dominant institutions are, as well as the institutional changes or creation of alternative institutions that social innovators seek to achieve. The transformation of society into a market society [

19] is an example of a deep change, which continues to be influential at the global level in a way that is coherently adaptive to diverse cultural contexts. While transformative change is oftentimes glorified as the most important or desirable type of change (especially among those seeking to bring it about), this is not necessarily the case for everyone or every situation. It is one type of change among many others that may be more appropriate in certain situations or contexts, while other types of change (e.g., incremental change) are equally or more appropriate in other situations [

20]. The 3D framework helps to be more explicit and intentional about the kind of change sought, i.e., the degree of depth, width, and length at which actors seek to intervene. The three institutional dimensions are briefly summarized in

Table 1, based on our original framework [

16]. See

Figure 1 for a graphic representation, emphasizing the degrees of institutionalization for each dimension.

Transformative changes and impacts can thus be assessed by identifying to what degree and in which way changes have been realized across each of these three dimensions. Often this can only be done in hindsight [

13]. Assessing impacts is more concrete than assessing transformative change in general, as impact focuses on how the interventions of particular actors have caused or contributed to transformative change. In the context of social innovation, the three dimensions can be used to assess how deeply embedded (depth), widely influential (width), and persistently reproduced (length) the institutional changes promoted by social innovators have become and to what extent they have challenged, altered, or replaced dominant institutions in relation to these three dimensions [

16]. Given the complexity of this kind of change, it is very difficult to identify causal attribution to individual actors or actions. Transformation is co-produced through highly dispersed agency [

22] of many actors and complex interactions with wider and longer-term societal and environmental factors. We prefer to speak of contributions of actors to transformative change that in some cases may be more easily identified or more straight-forward to attribute than in others.

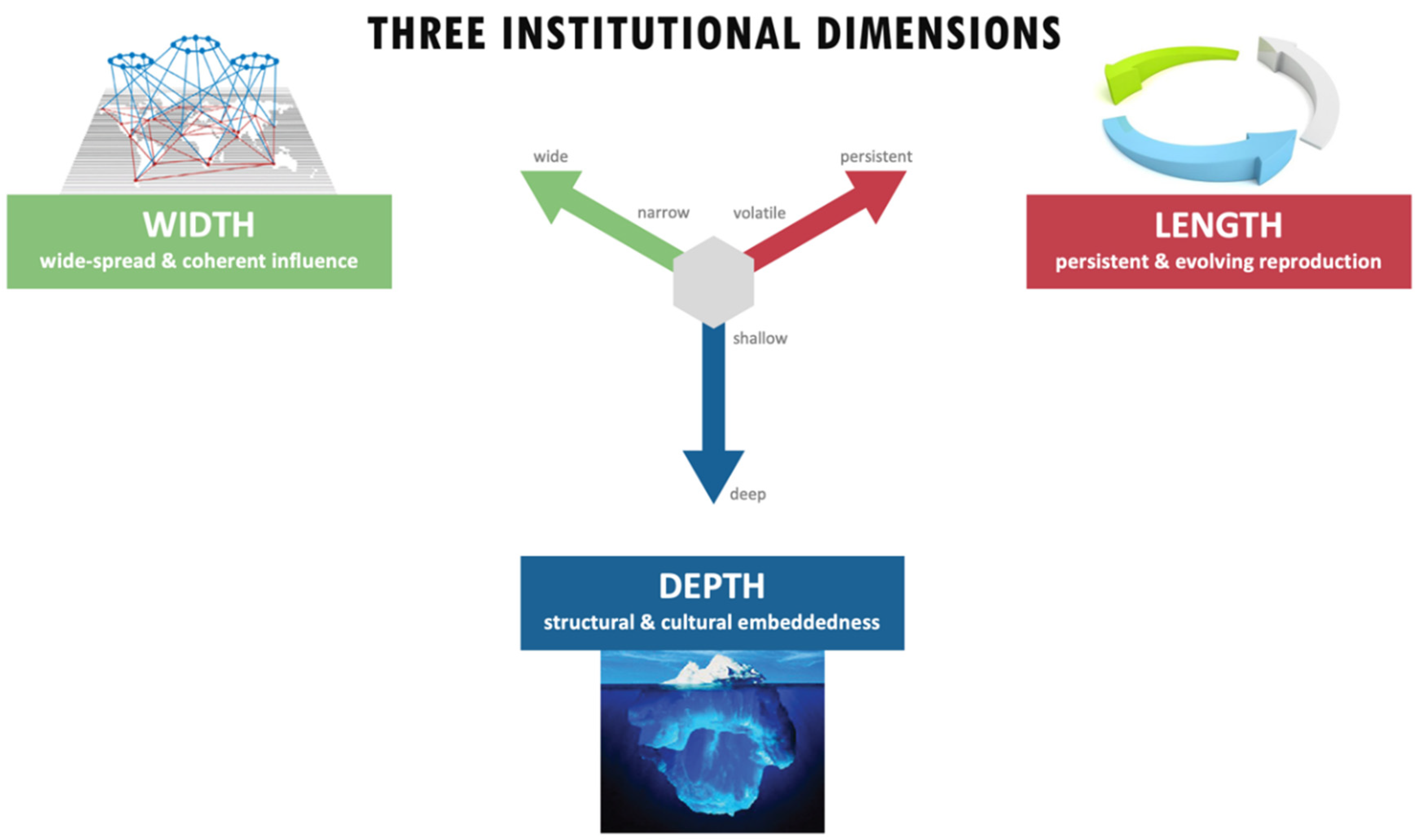

How to actually bring about transformative impact is a critical question: especially for social innovators aiming for transformation, as well as researchers seeking to understand or policy-makers seeking to support enabling conditions. We define transformative capacity as “the ability to turn transformative potential into transformative impact.” [

16] (p. 7). This involves a range of capacities among not only individuals but also collectives of social innovation actors who are connected via trans-local networks [

23]. By synthesizing results from the TRANSIT project (TRANsformative Social Innovation Theory—

www.transitsocialinnovation.eu) on TSI theory [

14,

24], we distilled twelve transformative capacities: four for each of the three institutional dimensions. These are presented in

Figure 2 and are not further elaborated here, as they are described in detail in our original framework [

16] (conceptually) and the rest of this article (empirically). By testing the conceptual framework in practice, some of these capacities have been revised or complemented by additional ones (see

Section 4 and

Section 5).

Note that in our initial framework [

16], we differentiated between transformative “competences”, which taken together constitute “transformative capacity”. However, during the application process we chose to use “capacities” instead of “competences”, for a number of reasons: Firstly, it became evident that the term “competences” unnecessarily increased the conceptual density of the framework, as it added to the already large number of concepts, which practitioners perceived as barriers for understanding and using the framework. Secondly, the notion of competences is generally more associated with properties of individuals, while capacities are also properties of groups, organizations, or networks as a whole [

25,

26,

27,

28], which is why capacity is more appropriate to the TSI context of collective agency [

9,

23].

The transformative capacities offer a capacity-specific lens on mechanisms of scaling or ‘trans-local diffusion’ [

13] of social innovation, as conceptualized in other typologies. These describe different dynamics of how social innovations initiatives develop and interact with dominant institutions: by growing, replicating, partnering, instrumentalizing, and embedding [

13,

29,

30,

31]; deepening, broadening, or scaling-up [

32], replicating, scaling-up, or translating [

33,

34,

35], replicating, scaling, and embedding [

36], shielding, nurturing, or empowering [

37], scaling out, scaling up, or scaling deep [

38]. The contribution of this study in relation to these other typologies is discussed in

Section 5.

4. Results

In this section we first describe the findings from applying the 3D framework elements: that is, we present empirical examples that substantiate what the framework elements meant concretely in the case contexts. We also describe how and why some of the original framework elements were refined, or new ones added, in response to the insights gained by applying the framework in practice. Consequently, we present the results about recognizability and usefulness of the 3D framework. Instead of analyzing each case separately from the perspective of the 3D framework, we describe overall patterns of transformative impacts and related capacities for each dimension, including diverse case examples.

4.1. Depth Impacts: Structural and Cultural Embeddedness

4.1.1. Recognition by Established Institutions

Representatives of the UN, national governments, and regional ministries are increasingly showing an interest in the ecovillage development approaches promoted by GEN and other community-led initiatives (PaOb-ECO, DocA-ECO). GEN has also come to be seen as a cooperation partner for universities, corporates, and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) (DocA-GEN). At a local level, some municipalities are very supportive of community-led initiatives and embrace them as innovative approaches. Examples include Steyerberg in Germany, promoting the electric car cooperative initiated by the ecovillage Lebensgarten Steyerberg (PaOb-GEN), or the Sustainable Neighborhoods program initiated by the municipality of Brussels (PaOb-ECO). However, many municipalities are also unsupportive or even block them (DocA-ECO). UNESCO and the German Council for Sustainable Development acknowledged the Green Office as a best-practice model to promote education for sustainable development. In some cases, such recognition involved financial support, in the form of prize money (e.g., the UNESCO-Japan Prize on Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), awarded to the Green Office model) or project funding (e.g., various EU-granted Erasmus+ projects for GEN, Transition Network, and ECOLISE).

4.1.2. Integration into Established Organizations and Policies

Unlike most student-led initiatives, established Green Offices are formally integrated as part of the university, receiving an official mandate, office space, salaries, and legitimacy to act for sustainability within their organization [

56]. Being structurally embedded and closer to decision-makers is a primary source of influence for Green Offices, setting them apart from other student groups. Many Green Offices have also achieved integration of education for sustainability in higher education curricula and organizational policies encouraging sustainable behaviors (e.g., recycling, vegetarian canteen options, or reducing single-use plastics). Integration can also involve creation of organizational entities, for instance, sustainability coordinators and committees (DocA-GOM), a secretary for peace-building in the Colombian ministry (Int-FMS), state-wide coalitions promoting and resourcing community-based solutions to gender-related violence (Int-RN), and the promotion of ecovillage development as part of the Senegalese government’s strategic policy (DocA-GEN). In a few countries (e.g., The Netherlands), ecovillages have succeeded in changing policies for land use and construction regulations to enable ecovillage development, or laws allowing for home-schooling (PaOb-GEN), while some Transition initiatives got municipalities to adopt renewable energy and reusable cup systems and convinced businesses to accept local currencies (DocA-TN). In Frome, UK, citizens even took over the municipality administration by supporting independent candidates standing for elections (DocA-TN).

4.1.3. Assessment Systems and Incentives

Some Green Offices conduct sustainability assessment and reporting and offer rewards for sustainability engagement of students: for instance, study credits, certificates (in partnership with academics), or coupons (in partnership with local businesses). Other activities by student-led initiatives, such as the national ranking SustainaBul (

www.studentenvoormorgen.nl/en/sustainabul) or the rating of business schools by Positive Impact Rating (

www.positiveimpactrating.org), assess higher education institutions and thereby incentivize them to improve their sustainability performance. Fundación Mi Sangre also works on changing assessment criteria by which students and teachers are evaluated, so as to create incentives to educate for whole-person leadership (Int-FMS). They also seek to create mechanisms whereby employers select and evaluate young people based on their sustainability competences (Int-FMS).

4.1.4. Changes in Values, Norms, and Behaviors

Green Offices have inspired students and staff to adopt sustainability values and related behaviors, such as vegetarian and vegan diets, energy saving, waste reduction, sharing resources, and expecting or inviting those behaviors from each other (social norms) (FocG-GOM, Int-GOM). Thousands of people who visit ecovillages to attend their courses change their lifestyles and initiate sustainability projects or community initiatives inspired by this experience (DocA-GEN). Some municipalities have adopted more participatory deliberation and decision-making processes as a result of cooperating with Transition initiatives and being inspired by their facilitation methods (DocA-TN).

4.1.5. Changes in Ways of Thinking (Mindsets, Beliefs, Discourses)

Some municipalities have changed their perception of community-based organizations as professional partners (DocA-TN). In some instances, university staff changed their view of students as competent and accountable change-makers (DocA-GOM). Prejudices towards low-income communities as dangerous slums changed as citizen-led graffiti tours in shanty towns shifted people’s image of these places (Int-FMS). GEN and Resonance Network contributed to wider acknowledgement of the role of worldviews as foundational for sustainability and peace-building (PaOb-GEN, Int-RN). Many educational organizations have realized the importance of supporting inner change for conscious leadership, while citizens see young people more as leaders and positive role-models, not just “typical leaders who are male and in their 50s” (Int-FMS). Widely influential ways of thinking can be barriers for SI models to become more widely adopted. For instance, ecovillages being seen as “hippie communes” (PaOb-GEN), or university staff not considering students as competent leaders (Int-GOM).

4.1.6. Changes in Power Relationships

Some university staff members remarked how the Green Office model challenges the traditionally more top-down relationship between staff or academics and students (PaOb-GOM), turning it into a more collaborative relationship on equal footing. Similarly, an example from Transition Network is a change in relationship through “approaching the council with an invitation, an offer, where the community is in the lead, rather than criticizing them or requesting to receive something” (DocA-TN).

This element was added to the 3D framework, as we recognized that the issue of power was not explicitly addressed in the original framework, while being a fundamental aspect of Transformative Social Innovation [

9,

57,

58].

4.2. Deepening Capacities

4.2.1. Understanding and Problematizing Root Causes

Most cases focus on raising awareness, especially among people who are not yet aware, of the urgency of sustainability challenges and how different systems (food, fashion, energy, transport, finance, etc.) contribute to problems of unsustainability and injustice. In the community-led cluster, the books, reports, or webinars of inspirational thought leaders or network leaders were seen as influential in building an understanding of systemic root-causes (Int-ECO, PaOb-GEN, PaOb-ECO). Examples include the writings and talks of Daniel Christian Wahl [

59] or Charles Eisenstein [

60] on the need for moving from degenerative socio-economic systems based on scarcity, separation, and extraction to abundance, wholeness, and regeneration. While less pronounced in the student-led initiatives cluster, in all cases it was found to be important to go beyond surface issues and to question established systems at a deeper level. Issues that were recurrently problematized were the capitalistic economic system geared to endless growth, individualistic consumer culture, patriarchy and neo-colonialism, a mechanistic worldview, and mindsets of separation and domination. One ECOLISE staff member suggested (Int-ECO) that many community-led initiatives could develop more systemic intervention approaches that identify and organize activities around systemic leverage points that are based on rigorous scientific systems analysis. He also mentioned that researchers could make a valuable contribution here.

This element was refined from “understanding and problematizing dominant institutions” in the original framework to be more concrete about the importance of identifying deeper root causes.

4.2.2. Identifying and Practicing Effective Solutions

Most of the efforts of the studied cases are focused on developing concrete events, projects, campaigns, and programs to promote the changes they wish to see (such as educational activities, festivals, conferences, consulting services). A shared mentality among the cases was to have a constructive and pragmatic approach by offering concrete solutions or alternatives to current problems, instead of (or in addition to) criticizing or demanding powerful decision-makers to act. In all cases, three levels of change activities could be distinguished: 1. the individual level (awareness raising, leadership development), 2. the collective level (community-building, community engagement, and networking) and 3. the systemic level (influencing policy and convening high-level leaders and decision-makers across sectors). Some cases found it important to develop rigorous theories of change (FocG-FMS), though a more common emphasis was on developing compelling visions or narratives of desired futures, as well as embodying or role-modeling the change they wish to see in individual behaviors and their organizational culture and structure (PaOb-ECO, PaOb-GEN, FocG-GOM). Most case networks developed elaborate solution inventories, success stories, and good practice guides to inspire and support effective action in different domains. Examples include GEN’s Solution Library (

www.ecovillage.org/solutions), Transition Network’s project examples (

www.transitionnetwork.org/do-transition/transition-in-action), or the good practice resources on the GO Movement website (

www.greenofficemovement.org/sustainability-resources).

This element was refined from “identifying and enacting solution pathways” in the original framework, as “identifying and practicing effective solutions” was considered to be more concrete and understandable in practice.

4.2.3. Clarifying and Enacting Core Principles and Values

For social innovations that are based on specific models that can be applied in different contexts (an ecovillage, a Transition initiative, or a Green Office) it was found to be important to distil the essence of those models into a set of core principles that encapsulate their transformative qualities. Examples are GEN’s Map of Regeneration (

www.ecovillage.org/projects/dimensions-of-sustainability), Transition Network’s healthcheck (

www.transitionnetwork.org/resources/health-check), and GO Movement’s Team Health Check (

www.bit.ly/GO-Health-Check). These principles describe the “essential ingredients” (DocA-TN) that are deemed to make these SI models effective in generating the desired changes: “It’s the most important secret sauce that we have, more than the methodology itself” (Int-FMS). Often these were developed over multiple years by synthesizing the learnings from what worked across diverse local adaptations (DocA-GEN, PaOb-GOM). The articulation of shared values (within and across social innovation networks) was of recurring importance, especially for those networks that were less focused on a specific model (PaOb-ECO, Int-FMS). Examples in the ECOLISE context were: care, cooperation, co-creation, social justice, and ecological integrity (DocA-ECO). ECOLISE members emphasized that it is especially important to operationalize those values in action (Int-ECO, PaOb-ECO). Similarly, oikos makes values a core element of their organizational culture and also supports students to clarify and enact their values on a personal level, so as to become responsible leaders in their careers (PaOb-OI). Values were generally seen to act as a core mechanism for embodying the change that social innovators wish to see, and to avoid co-optation by institutions they wish to change (Int-ECO, PaOb-ECO).

This element was refined from “clarifying, enacting, and maintaining core values” in the original framework, as we found that the aspect of “maintaining” belongs instead to lengthening capacities (“generating continuity of activities and resources”) and the following deepening capacity.

4.2.4. Cooperating Strategically and Reflexively across Sectors

All cases emphasized the need to cooperate with high-level decision-makers in government, business, or academia to further their transformative ambitions or address complex challenges in integrated ways. They lobby for formal recognition and supportive financial or legal frameworks, apply for funding or formal mandates, or invite partnerships for collaborative action. Having good relationships with people in those institutions (e.g., Members of the European Parliament, faculty deans in universities, council members in municipalities) who support their cause was seen as critical.

However, “cross-sector gaps” (Int-ECO) were seen as challenging, for various reasons. Oftentimes, misunderstanding, skepticism, or prejudice (e.g., “anti-private sentiments”, businesses as “the enemy”) were seen as barriers for community-led and student-led initiatives to cooperate with public and private actors. Hence, “the art of convening” (FocG-ECO) to create trust, understanding, and willingness to cooperate across sectors was deemed important. Transition Network initiated the Municipalities in Transition project (

www.municipalitiesintransition.org) to strengthen cooperation among municipalities and Transition initiatives. ECOLISE cooperates with the European Rural Parliament (PaOb-ECO), while some ecovillages cooperate with farmers, citizen groups, and municipalities for spreading their solutions in traditional villages (see the “Living in Sustainable Villages” project by GEN Germany:

www.gen-deutschland.de/leben-in-zukunftsfaehigen-doerfern). Green Offices cooperate with other student groups, staff initiatives, companies, and municipalities for joint projects on awareness-raising, behavior change, and institutional change projects (FocG-GOM, DocA-GOM).

Maintaining autonomy and not losing their radical edge was seen as a challenge when cooperating or receiving institutional support. Cooperation may require making compromises in favor of the interests or requirements of funders or decision-makers. For instance, a few Green Offices have lost some of their student-led qualities as they had to give way to more powerful staff-led initiatives (Int-GOM). Similarly, some town councils have appropriated the actions of Transition initiatives [

61]. Hence, all cases found it important to find ways of avoiding or dealing with such situations and reflect critically about how core principles may be lost, or dominant institutions reproduced in undesirable ways. This tension between cooperation and autonomy was often found to be difficult to navigate.

This element was refined from “interacting strategically and reflexively with dominant institutions” in the original framework, as emphasizing cross-sector cooperation was seen as more concrete. It also made this element more distinct from the widening capacity “cross-movement collaboration”.

4.2.5. Challenging Dominant Power-Structures

The nature of power structures is a topic that was discussed in many of the networks studied. This topic was frequently seen as deserving more explicit attention and practitioners found that more skillful ways of dealing with issues of power need to be learnt (PaOb-ECO). Various “systems of oppression” were mentioned (PaOb-ECO, PaOb-SOS, FocG-RN), such as white supremacy, racism, neo-colonialism, patriarchy, or classism [

62,

63,

64]. Many practitioners perceived it as foundational to create conditions for inclusivity, equity, and diversity, since transformative ambitions will have little impact if socially innovative solutions only remain accessible to the privileged (i.e., less width), or if they unwittingly perpetuate deeper power structures as part of their activities and organizational structures (i.e., less depth). For the studied cases, this involved not only challenging external structures (e.g., campaigning against unjust policies) (Int-RN), but also internalized power structures; for example, by “unlearning” sub-conscious attitudes, such as a “capitalist mindset” (FocG-ECO), and habits, such as giving less credit to female or non-white voices (PaOb-GOM, Int-RN). Some cases developed specific guides, practices, or workshops to strengthen this capacity (DocA-GEN, DocA-TN, PaOb-SOS).

This element was added to the 3D framework, as we recognized that the issue of power was not explicitly addressed in the original framework, while being a fundamental aspect of Transformative Social Innovation [

9,

57,

58].

4.2.6. Reconciliation and Healing of Trauma

Addressing issues of reconciliation and restorative justice in relation to historical oppression, violence, and exploitation (resulting from neo-colonialism, racism, patriarchy, etc.) was seen as deeply important in the contexts of community-led initiatives and citizen-led peace building. Recognizing and addressing such deep-seated wounds not just in individuals but among oppressed communities (indigenous, non-white, etc.) plays a central role in the peace-building work of Fundación Mi Sangre and Resonance Network (Int-RN, Int-FMS). GEN co-organized a Collective Trauma Online Summit (

www.collectivetraumasummit.com), which emphasized the fundamental role of trauma in re-producing collective systems of violence and unsustainability, affecting humanity as a whole. In the Transition network, people involved in ‘Inner Transition’ [

65] groups “realized how much of the violence we inflict on nature and others comes out of the violence we inflict on ourselves on the inside. Working on regeneration is healing this inner violence” (FocG-ECO). Inner Transition groups support people to undergo profound psychological and cultural change to respond to global challenges, while avoiding burnout and nurturing personal and planetary well-being.

This element was newly added to the original framework, as it surfaced in two of the three case-clusters as one of the deepest dimensions of transformation, while being often overlooked (indeed, also in our original framework). We also deemed it important to include this element, considering projections that intensifying climate-change related crises (which tend to affect the marginalized more than the privileged) will surface historical wounds of injustices and oppression [

66,

67,

68] and that addressing these is core to the psycho-cultural aspect of deep societal transformation [

66,

69].

4.3. Width Impacts: Wide-Spread and Coherent Influence

4.3.1. Geographical and Cultural Spread

The studied cases have spread their social innovation models and approaches in countries around the world, to varying degrees. For instance, around 10,000 ecovillages and similar intentional communities exist globally in both traditional villages and newly set up communities (DocA-GEN). Around 1200 Transition initiatives exist in 50 countries (DocA-TN). A total of 47 Green Offices exist in nine countries and more are launching every year; though, with a few exceptions most Green Offices are located in northern and western Europe (DocA-GOM). So far, 49 local oikos chapters exist in 23 countries across the globe (DocA-OI). Yet, while there may be many of such models in a given country, the reach and engagement are often still limited to groups who are already aware, interested, or able to engage in the solutions these initiatives promote. While individual Green Offices reach hundreds if not thousands of students and staff with their activities, these are often from sustainability-oriented study programs or people interested in ecological sustainability. Only a few reach beyond more privileged socio-economic populations to those generally most vulnerable to threats of climate change (PaOb-GOM). Similarly, many northern ecovillages are mainly known by sustainability-minded people and often accessible only to those with sufficient financial resources (PaOb-GEN).

4.3.2. Adaptation to Diverse Contexts

As the studied networks spread their social innovations, they have also been adapted to suit different kinds of cultural, geographic, socio-economic, and organizational contexts. Ecovillages and some of the solutions they promote have been adapted to traditional villages in southern contexts, some also in cities (eco-neighborhoods, urban ecovillages) (DocA-GEN). Some ecovillage solutions are being applied in schools, refugee camps, and areas afflicted by natural catastrophe. The Transition model itself can be seen as an urban outgrowth of ecovillage and permaculture movements (DocA-ECO). The Transition approach has been adapted in towns, villages, cities, universities, and schools (DocA-TN). Besides traditional universities, Green Offices are also increasingly being adapted at universities of applied sciences, some professional colleges, and two exist at a school and a municipality.

4.3.3. Coherence of Core Principles across Diverse Adaptations

The social innovation models studied are adapted to local contexts in highly diverse ways, unlike more traditional franchise models. A recurring pattern was observed that local groups differ according to how strongly they are aligned with the core principles that make these models (potentially) transformative. For example, some ecovillages have well-developed activities in all four dimensions of sustainability (PaOb-GEN), and some Green Offices demonstrate strong institutional influence and community engagement (PaOb-GOM). Others only embody these elements to a lesser degree, as they have other needs, priorities, or ambitions, or are more constrained by context conditions. However, as many of the networks were in the process of gathering data to assess coherence at the time of this study, little concrete evidence could be found for this element.

4.4. Widening Capacities

4.4.1. Spreading and Adapting SI Approaches to Diverse Contexts

GEN and GO Movement have various courses, trainings, learning materials, consulting services, and ambassadors for spreading their ecovillage and Green Office models. GEN runs a variety of programs for spreading ecovillage approaches in traditional villages, schools, refugee camps, and areas of natural catastrophe and offers consulting for development ministries to adopt ecovillage development, especially in southern countries (DocA-GEN). GO Movement team members offer consulting, workshops, and online courses and spread the Green Office model via conferences and active outreach and support to students and staff in different countries and organizations (PaOb-GOM). Again, the ability to distil core principles that encapsulate the essence of these models was a catalyst for spreading them more widely and adapting them (PaOb-GEN). At the local level, individual ecovillages and Green Offices also organize activities, such as courses, conferences, and festivals, to inform, engage, and support people to adopt sustainable behaviors and values. A common emphasis for student-led and community-led initiatives lies on showcasing working examples of solutions people can engage with and the importance of storytelling to make these solutions and their vision for change attractive and convincing. Another common concern was replicability of their models in contexts with less wealthy or supportive institutional contexts than northern and western Europe (PaOb-SOS, PaOb-ECO).

4.4.2. Engaging a Variety of People and Perspectives

For most cases studied it was highly important to widen the radius of people they are able to attract and engage as participants, members, or ambassadors. Some have created programs or organizational conditions to make their models and activities accessible to and inclusive of diverse people with regard to income-levels, socio-economic status, identities (national, racial, religious, sexual, etc.), abilities, interests, etc. For example, most Green Offices offer volunteer engagement opportunities to reach well beyond their core team and some partner with study associations to engage student populations of various disciplines and interest groups (FocG-GOM). GEN have created programs to adapt ecovillage solutions to refugee camps. Equity, diversity, and inclusion are recurrent topics across community-led initiatives (though to varying degrees), especially reaching beyond privileged white middle-class populations (PaOb-ECO). However, this can also be the other way around when social innovators are working specifically with under-privileged people: a representative of Fundación Mi Sangre stated that they could widen their engagement by involving more upper-class people and training more highly-educated students as leaders, as their focus has been low-income communities so far (Int-FMS). A few focus group participants observed that social innovators can tend to operate within the comfort zone of like-minded, like-abled, like-educated, etc.; however, “transformation happens at the edges of comfort zones” (FocG-RN). A recurrent challenge mentioned was using language that resonates more widely with people who are not yet familiar with the topics promoted by SI actors, while avoiding appropriation or dilution of core values and principles (PaOb-ECO).

4.4.3. Cross-Movement Collaboration

Collaboration with initiatives or networks with similar visions was seen as important for all cases for various reasons: to exchange strategies, spread successful activities at wider geographic scales, and build synergies among complementary approaches that different initiatives or networks offer. For example, the GO Movement adopted the Green Impact program (a staff-focused behavior change program) from the National Union of Students in the UK and delivered it in the Netherlands and Belgium while integrating it with the Green Office model (PaOb-GOM). For this to work, the importance of building trust-based relationships and bridges across a diversity of movements was repeatedly emphasized (PaOb-SOS, PaOb-ECO). The meta-networks ECOLISE and SOS play a key facilitating role in strengthening trust-building, communication channels, exchange of experience and projects, and devising joint activities across movements (e.g., ECOLISE’s European Day of Sustainable Communities:

www.sustainable-communities.net). Some emphasized the importance of going beyond the “usual suspects” and collaborating with diverse, or “provocative” kinds of movements (e.g., hackers, social justice activists, indigenous groups) to expand perspectives and confront one’s assumptions (PaOb-ECO, FocG-FMS). However, exclusion of partners can also be part of the bridging process, when core values, agreements, or the image of a movement are threatened [

70].

This element was refined from “cooperating with other actors” in the original framework, to more concretely differentiate “cross-movement collaboration” as a widening capacity and “cooperating strategically and reflexively across sectors” as a deepening capacity.

4.4.4. Building Coherence across Diversity

Defining what an ecovillage is was an ongoing discussion with many divergent opinions in the ecovillage movement. GEN helped to build coherence by co-creating a definition, a set of core principles (the ‘Map of Regeneration’), and a glossary of terms that are agreeable for many. Their principles have also been translated into an Impact Assessment tool (

www.ecovillage.org/resources/impact-assessment) and a card deck that can then be used by ecovillages, trainers, and consultants to evaluate and design ecovillages in a way that aligns with these core principles. Similar approaches were seen with Transition Network’s healthcheck, which describes “essential ingredients” (DocA-TN) of Transition and offers trainings and learning materials for each. In the GO Movement, six core principles were developed, plus three different archetypes of how these principles can be applied in different university contexts. GO Movement’s Team Health Check tool (inspired by Transition Network) and the GO Impact Evaluation tool (based on the 3D framework, see

Appendix C) support coherence building, as well as workshops, online courses, and peer learning events. Network coordinators of GEN, Transition Network, and the GO Movement were concerned that the overall impact, image, or legitimacy of their respective networks can be weakened if only a small percentage of local groups apply these core principles, or if any group can use their label without practicing these principles.

4.5. Length Impacts: Persistent and Evolving Reproduction

4.5.1. Long-Term Persistence of SI Approaches

So far, 95% of Green Offices have persisted beyond their initial funding period (typically one to two years), while 5% have been closed down after a few years of activity and a few more have seen their budgets being cut. However, the vast majority have been able to maintain or increase their size and institutional support over time, as well as the size and quality of projects and relationships within and outside of the university (PaOb-GOM). Many ecovillages have existed for over 30 years, demonstrating the viability and durability of ecovillage approaches, if strong foundations are in place. On the other hand, 90% of newly starting ecovillage initiatives disband within their first year due to internal difficulties (PaOb-GEN).

4.5.2. Continuous Individual Engagement

Green Office alumni who participated in the online summit stated that their experience of working at the Green Office significantly empowered them to continue acting as sustainability change-agents after their studies (FocG-GOM). Similarly, many oikos alumni became influential leaders for sustainability in their careers in business, finance, and management (PaOb-SOS). This was seen as related to the deep learning experiences from their involvement in the Green Office or oikos movements, where they developed sustainability values and change-maker attitudes and competences. In the ecovillage context, the continuous leadership of youth growing up in ecovillages like Tamera can be seen as a persistent impact, considering that some ecovillages lose momentum as the founding generation grows older (DocA-GEN).

4.5.3. Increases in Width and Depth over Time

Generally, during the framework application it became evident that the framework element “evolving reproduction” was difficult to distinguish from the lengthening capacities “evolving goals and strategies” and “maturing along developmental stages” (see

Section 4.6), or from changes in depth and width impacts (

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.3). We therefore found that evolutionary development impacts can be understood as increases over time in the width and depth dimensions of impact, rather than being a separate category of transformative impact. For instance, in a few universities the activities of Green Offices have led to more staff-led sustainability approaches being initiated, in addition to the student-led Green Offices (increasing levels of structural embedding) (Int-GOM). Also, these students and staff-led activities have become more integrated in some universities (increases in coherence) (Int-GOM). However, in at least one instance the stronger focus on staff-led approaches curtailed the influence and autonomy of the Green Office (decrease in embedding and persistence) (Int-GOM). Also, the fact that the Green Office model was applied to the municipality in Amsterdam (DocA-GOM) (increase in spread and structural embedding) could be seen as an evolutionary development.

4.6. Lengthening Capacities

4.6.1. Generating Continuity of Resources and Activities

Finding sources of continuous funding was often seen as foundational to ensure persistence of social innovations. Most Green Offices receive annual budgets for salaries and projects from their universities thanks to their lobbying efforts (PaOb-GOM), while oikos chapters mostly apply for project funding from private donors and foundations (PaOb-OI). The studied networks commonly explore mixed income models that combine different funding sources, including foundation grants, prize money, public funding for educational programs or knowledge development projects, membership fees, and selling services, such as workshops or courses (PaOb-SOS, PaOb-ECO). However, most of the studied cases only have few, if any, paid staff positions for network coordinators and local groups and rely heavily on volunteers and unpaid extra hours from staff. So, besides finding viable financing models, they also need to secure ongoing motivation and engagement among volunteers, as well as transfer of knowledge, stakeholder relationships, and projects across people joining and leaving these initiatives, sometimes in relatively short cycles. Most cases highlighted the need for creating livelihoods and professional work opportunities, to go beyond volunteerism. For student-led initiatives, continuous engagement of alumni after graduating was another continuity challenge, given their ambition that graduates become sustainability change-makers in their careers (PaOb-SOS). In ecovillages, continuity also applies to cross-generational transfer of the knowledge, attitudes, etc., for youth who grow up in ecovillages to continue living in and co-developing those places (PaOb-GEN). For southern contexts, ecovillage approaches also focus on maintaining existing traditions and community relations to avoid their replacement by western development approaches (PaOb-GEN).

This element was adapted from “generating continuity of resources, activities, and essential elements” in the original framework, as the notion of “essential elements” was found to be too vague by practitioners. Aspects such as values, knowledge, motivation, principles are considered part of resources and activities.

4.6.2. Ensuring Resilience in the Face of Challenges

Considering that 90% of ecovillage initiatives fail within their first year due to internal group conflicts, GEN developed a good practice guide (clips.gen-europe.org) and related trainings to help initiatives overcome such difficulties (PaOb-GEN). For instance, key capacities addressed by the guide are having a clear shared vision, written agreements, and processes for decision-making and dealing with conflict. Resources on comparable topics could be found on the websites and support offers of Transition Network and the GO Movement. Ensuring continuous support from municipalities or university decision-makers is another key lengthening capacity for Transition initiatives and Green Offices, as the continuity of their resources and activities can be threatened by changes in elected public officials or university presidency (DocA-TN, PaOb-GOM). Building supportive relationships with multiple staff or technicians who stay in their positions for longer time than elected officials was seen as a key condition to overcome this challenge (DocA-TN, PaOb-GOM). Responding to external challenges, such as funding cuts, natural disasters, or the recent COVID-19 pandemic also requires social innovators to respond in creative ways to avoid a discontinuity of their efforts (PaOb-GOM, DocA-GEN).

4.6.3. Evolving Goals and Strategies

This involves further developing core principles, theories of change, narratives, and related strategic interventions over time. For example, Transition Network changed their narrative from “responding to peak oil” and threats of economic and climatic instability, to “rebuilding and re-imagining our communities”, as they realized that such positive framings were more conducive to getting people engaged (DocA-TN). Another example is that most cases are moving more of their activities (meetings, conferences, workshops, etc.) online to bridge geographic and cultural gaps and increase accessibility (PaOb-SOS, PaOb-ECO). Many cases also highlighted the need to be able to change what is not effective and navigate complex change processes with flexibility and responsiveness to learn and adapt over time (PaOb-ECO, PaOb-GOM). For instance, initial GO Movement leaders shifted from a for-profit consultancy approach to an open-source movement approach, after realizing that it was difficult to sell consulting services in this sector and that they could have much wider impact via freely spreading the GO model (PaOb-GOM). Yet, some cases expressed difficulties with being confined by requirements of funders to deliver programs according to fixed goals and plans. However, founders of social innovation initiatives can also block further evolution if they are overly attached to their vision or seek ownership or control in place of inviting co-creation (PaOb-SOS).

Many also stated the importance of accelerating their efforts to “go further, faster”, in response to the rising urgency of societal problems (PaOb-SOS). An ECOLISE staff member emphasized the importance of responding to societal trends of rising awareness and perceived urgency of climate change, “to step up and showcase the decades of work that has been done to offer viable alternatives […] and step in from the margins to the center and show ready-to-go initiatives” (PaOb-ECO). Yet, ECOLISE and SOS members also cautioned that such acceleration needs to be balanced with taking the time to slow down, reflect deeply, and support initiatives to mature, instead of “growing too fast” and risking dilution of core principles (FocG-ECO, PaOb-SOS).

This element was adapted from “evolving core characteristics” in the original framework, as “goals and strategies” made this more concrete.

4.6.4. Re-organizing and Decentralizing Governance Structures

As the studied cases grew and matured over time, many needed to re-organize their organizational structures and processes. Members of ECOLISE and Transition Network emphasized the need to go beyond traditional hierarchical organizational structures found in most NGOs, companies, and governments and adopt more innovative, agile, and participatory structures (PaOb-ECO). Stated reasons included the need to be 1. more responsive through faster and better decision-making that is aligned with needs of members and changing context conditions, and 2. more inclusive through engaging a larger number and diversity of people. Sociocracy and other forms of decentral self-organization within and across networks were found in Transition Network, GEN, and ECOLISE.

The formation of multi-layered networks was common across cases as one way of decentral organizing. For instance, besides the global network, GEN formed national (Germany, Netherlands, etc.) and regional (Europe, Asia, etc.) constituent networks (PaOb-GEN). Similarly, oikos initiated regional and thematic groups (PaOb-OI) for oikos chapters to connect according to geographic proximity or shared interests. Decentralization can also apply at the local level of individual initiatives. For instance, Green Offices initiated volunteer teams or ambassadors at different faculties or campus locations who work in coordination with a central Green Office (Int-GOM).

Decentralization was seen as an important lengthening capacity for multiple reasons. It can strengthen resilience, as local groups and the network at large are less dependent on the continuity or effectiveness of central individuals or organizations (Int-GOM, PaOb-GOM, PaOb-GOM). It can also help with accessing resources at different levels (e.g., local, national, and transnational, e.g., EU or UN funding streams) (PaOb-ECO).

This element was added, as a more specific and distinct framework element that was previously considered part of “evolving core characteristics” and “maturing along developmental stages” in the original framework.

4.6.5. Maturing along Developmental Stages

Being able to build on and learn from past efforts was seen as key for social innovators to develop more sophisticated solutions over time. For instance, in ecovillages intergenerational knowledge transfer is a key issue: “movement building requires accumulative knowledge so that each younger generation doesn’t start at square one again” (DocA-GEN). Most networks studied give bountiful attention to capturing the learnings from diverse local groups and making those visible and accessible for others to build on (through courses, trainings, conferences, guides, wikis, etc.). Green Offices and Transition initiatives tend to develop in similar phases—initiating, starting, expanding, and re-structuring—and specific support is offered for each of those developmental stages (DocA-TN, DocA-GOM).

The studied networks also went through different stages of development. An ECOLISE staff member suggested that the development of national, international, and transnational network structures (such as ECOLISE) is itself a sign of maturation of community-led initiatives (Int-ECO). This was seen as maturation, as the member networks like GEN and Transition Network first needed to mature internally before they could organize in more complex ways and collaborate across movements (Int-ECO).

Finally, maturing also applies at the individual level. All networks studied focus on supporting individuals to develop to more sophisticated levels of competence, engagement, and leadership: for example, from attending an event, to signing up to a course, to joining as a member and taking on more responsibilities in the initiative or promoting the desired changes in wider society. A recurring approach was to offer diverse pathways for individuals to develop their competences and levels of engagement over time (PaOb-GEN, DocA-TN, PaOb-ECO, PaOb-SOS).

4.7. Recognizability

Overall, the framework appeared very much aligned with what practitioners deem important or necessary for transformative change to occur. In many of the discussions and workshops attended, conversations naturally focused on many of the elements in the framework without having introduced the framework to them beforehand. Many practitioners were very enthusiastic about the framework after explaining it to them during participant observation events, focus groups, and interviews. For example, during a focus group at an ECOLISE workshop, one participant responded that “the elements capture most of the critical components of transformative capacity” (FocG-ECO). Similarly, a network leader from GEN remarked: “this is fantastic, it speaks so much to the questions we are asking in GEN” (FocG-ECO). Another participant found it an “elegantly simple representation of complexity, without being simplistic. This is difficult and rare” (FocG-ECO). For all cases the intention of the framework resonated with their understanding that for realizing their transformative ambitions, it is critical: 1. to identify the kinds of capacities needed for social innovation actors to be effective, and 2. to learn how to create contexts for developing those capacities. For this reason, a few respondents offered significant support in co-organizing and facilitating focus groups to test the framework and provide feedback about the framework elements.

Critical points were raised on three issues: 1. the use of abstract concepts, 2. unclear categories, and 3. unclear language. Firstly, some of the framework elements were seen as quite abstract and as such difficult to understand or relate to, without concrete examples or case-specific questions. In response to this, sub-questions for each of the framework elements were developed (

Appendix B), as well case-specific indicators for some of the cases (see

Section 3.3 and

Appendix C). Secondly, when applying the 3D framework, some were unsure which of the three dimensions a certain impact or capacity belonged to: e.g., “is maintaining core values a lengthening and/or a deepening capacity?” (Int-RN), or “when many organizations changed their culture is that width [wide spread] and/or a depth impact [cultural embedding]?” (Int-FMS). This speaks to the high degree of interaction among the three dimensions, which is further discussed in

Section 5 (also see

Appendix D). Thirdly, some found certain notions confusing or unclear, such as “social innovation (SI) elements” and “dominant institutions”: “are dominant institutions political parties, or organizations like universities, schools or companies? Or things like patriarchy, white supremacy, etc. that often underly those institutions?” (FocG-RN). These terms were therefore clarified or avoided in the refined elements of the 3D framework.

About the notion of “transformative impact”, a few practitioners expressed the difficulty of knowing if or how their activities have caused or contributed to those impacts and how to differentiate this from general changes they have observed in society that may have come about due to a variety of factors. Indeed, impacts are co-produced and causality notoriously difficult to ascertain. Therefore, we emphasized the focus on contributions to transformative impact, recognizing the role of other actors and factors in co-producing impacts (see

Section 2). One focus group participant stated that it “felt like a revelation to see the impact of my network versus impacts of other networks […] that transformative impact is not something one network can achieve alone. It was valuable to be challenged to think beyond our own impact as an organization” (FocG-FMS).

A recurring point of confusion was that many case respondents tended to focus on the embeddedness, influence, or persistence of a specific project or campaign instead of the social innovation (SI) elements. To clarify: in the 3D framework the important question regarding transformative impact is how deeply embedded, wide-spread, and persistent those SI elements are. For instance, this would mean that community-based regenerative ways of working and living have become a norm in economic development approaches, or student leadership for sustainability has become a norm in higher education curricula and governance. A large degree of length would entail a persistence of those elements independent of the continuation of organizations, such as GEN or Transition Network, who promote them. This could be the result of those elements being deeply embedded and widely spread in many organizations and societies.

One ECOLISE member mentioned that he struggled to understand how the 3D perspective helps to tackle the inertia of dominant institutions, recognizing that all the efforts in community-led initiatives have yet achieved rather little to fundamentally change these (FocG-ECO). Possible responses could be that it can be used to identify ways of challenging the spread, persistence, and embeddedness of those institutions (awareness-raising, unlearning, offering alternatives), or using the 3D perspective to develop the capacities that can enable deep and wide-spread scaling of alternatives offered by social innovations, once established institutions become increasingly unstable or eventually collapse.

4.8. Usefulness

The most common response of practitioners was that they found the 3D framework very useful as a lens for understanding and reflecting about transformative impact and what is needed to make it happen: as a way to be more aware of and intentional about one’s impacts and strategies. The representative of Fundación Mi Sangre saw it as a “very useful framework to describe the impact at different levels, much more than what we use to do that today”. She added that “it’s the first clear, schematic, and simple framework to analyze and to describe everything we’ve done”, in contrast to other frameworks for system change or scale that only focus on some of these elements. Recognizing that “simple” could be seen as something negative (i.e., simplistic), she clarified that she sees it as “very valuable precisely because of the simplicity” (Int-FMS). A few respondents also emphasized the value of collectively reflecting and exchanging perspectives with their colleagues about the framework elements (FocG-FMS, Int-ECO).

For initiatives that are still in the initial stages of development, the framework was also seen as useful to intentionally consider all the elements when designing their interventions (Int-FMS). One network leadership expert suggested that for many networks she knows of, thinking about transformative impacts and capacity is “really new stuff” and that it would be very relevant for them to consider this framework to be more intentional and strategic specifically about transformative change and to realize how their current efforts may be less than transformative: “It really gives them a tool to take the blinders off. People often realize that values are key, but many other ones [transformative capacities] they are not doing at all.” It was seen as “a language to guide strategic reflections, a way to identify actions to take to move in all three directions, and to situate different actions in each dimension” (FocG-FMS).

Many practitioners were very interested in how this framework could help them with the following needs: their impact assessment and reporting to garner support from funders and policy-makers, having an external point of view in addition to internal reflections, comparing assessment results with other organizations, as well as having a benchmark to analyze how advanced an SI initiative is in different dimensions (FocG-ECO, FocG-FMS, Int-RN). Many also expressed the need for developing more specific quantitative and qualitative indicators, based on the more generic elements in the 3D framework. It was suggested that these indicators should be tailored to their activities at different levels, depending on what they wish to focus on: from individual events, projects, and programs to an entire organization, network, or network of networks (FocG-ECO). A related suggestion was to develop more concrete rubrics or check-lists for each of the framework elements, so as to make it easier for practitioners to evaluate how well-developed their activities are in each area. Also, finding a way of merging those different levels of assessment into “some form of overarching indicators” was seen as a needed development of the framework to make it more useful (FocG-ECO).

While some practitioners appreciated the simplicity of the 3D perspective in general, the 3D framework was also found to be challenging to operationalize for assessment and goal-setting. This was due to the generic quality of the framework elements and the complexity of the number of elements and interactions to consider (Int-ECO, Int-GEN). When adapting the framework elements to the GO Movement context (see

Appendix C), it became evident that they needed to be reduced in scope, simplified, and made specific to issues relevant for Green Offices. GEN and ECOLISE were still in the process of clarifying their strategic goals at the time of this study. Hence, they expressed that they first needed to clarify their goals internally, before the 3D framework could be operationalized into case-specific indicators. For them, the 3D framework was seen as more useful for refining goals and indicators they already articulated, instead of taking the framework as a starting point (Int-ECO, Int-GEN).

Some ambivalence was expressed about the usefulness of distinguishing transformative impact and transformative capacity among ECOLISE staff. Some perceived this as very useful, as it highlights the difference between what practitioners have achieved or seek to achieve (transformative impacts) versus that which is needed for them to be able to do so (transformative capacity). Yet, for others, “building transformative capacity and achieving impacts are so closely related as to almost make the distinction unhelpful” (PaOb-ECO). While acknowledging this inter-relatedness, we hope that the concretization of the framework helped to make the value of this distinction clearer. An interviewee from Fundación Mi Sangre also stated that the distinction between the diagnostic questions about impacts achieved and envisioned impacts helped to clarify capacity gaps: “what we need to nurture to ensure that we continue developing our impact” (Int-FMS).

A few practitioners also expressed a need to prioritize which of the elements in the 3D framework to focus on. A network leader from Transition Network expressed a perceived risk of such comprehensive frameworks to add to a sense of overwhelm, experienced by many social innovation practitioners: “many struggle with burn-out, given the complexity of working towards transformative change and shortages of time and money” (FocG-ECO). Instead of pointing out all the conditions one needs to think of, she suggested identifying the core strengths or niche of a network (e.g., in the domain of deepening) and focusing on building synergies with allied networks that have complementary strengths (e.g., widening). She stated the importance of finding the “reassurance of doing this work as part of a wider ecosystem” (FocG-ECO). When testing the framework as an evaluative tool, it was also suggested to prioritize a selection of key issues to address, as well as define actionable implications for strategic improvements (Int-FMS).

One suggestion for turning the framework into a “useful knowledge format” was to formulate a “pattern language” [

71] (Int-ECO). This involves describing a set of patterns as recurring problem and solution statements that are applicable to many different contexts, as well as describing how they are connected to each other. This is an approach employed by ECOLISE [

72], Transition Network (

www.patterns.transitionresearchnetwork.org), and other social innovators (for example: group collaboration patterns:

www.groupworksdeck.org; Sociocracy 3.0 patterns:

www.patterns.sociocracy30.org) [

73]. The transformative capacities presented in this article can offer an initial step in developing a pattern language that includes concrete practices for supporting capacity development and makes more explicit how these are connected.

5. Discussion

In this section we discuss our main findings and their significance for social innovation research and practice, reflect on the limitations of this study, and provide recommendations for future research.

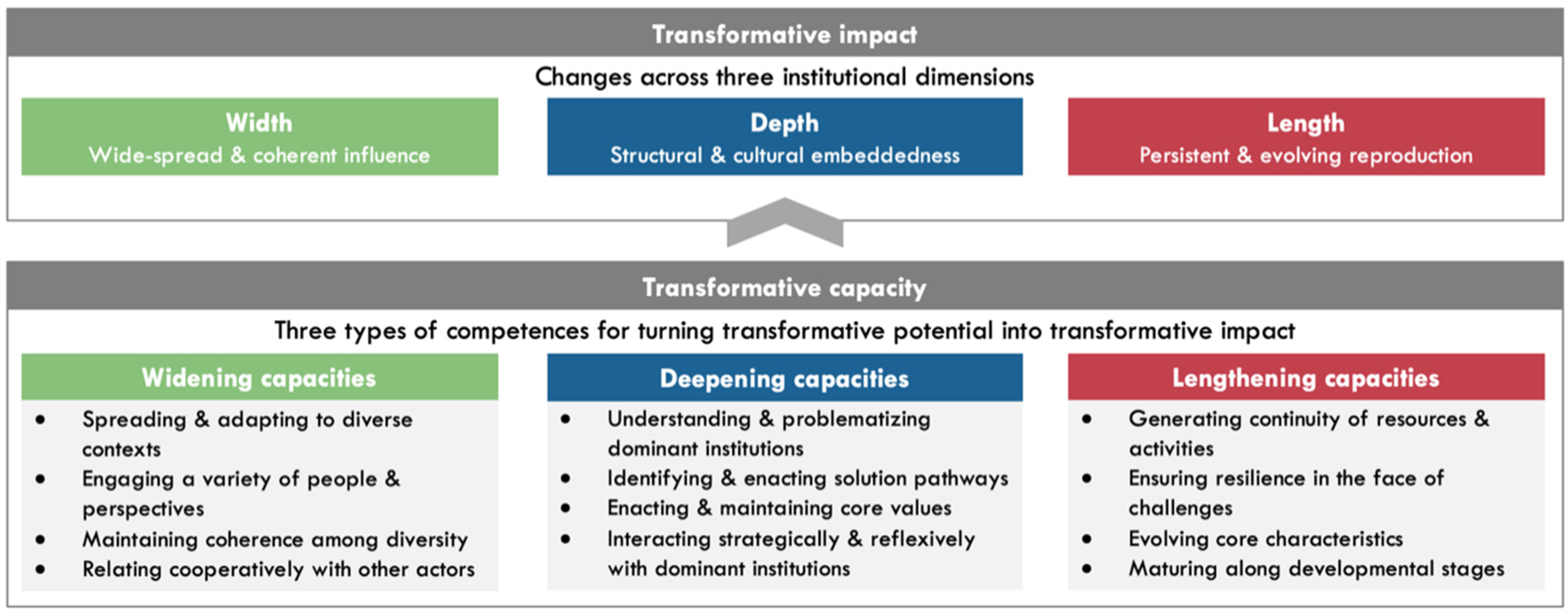

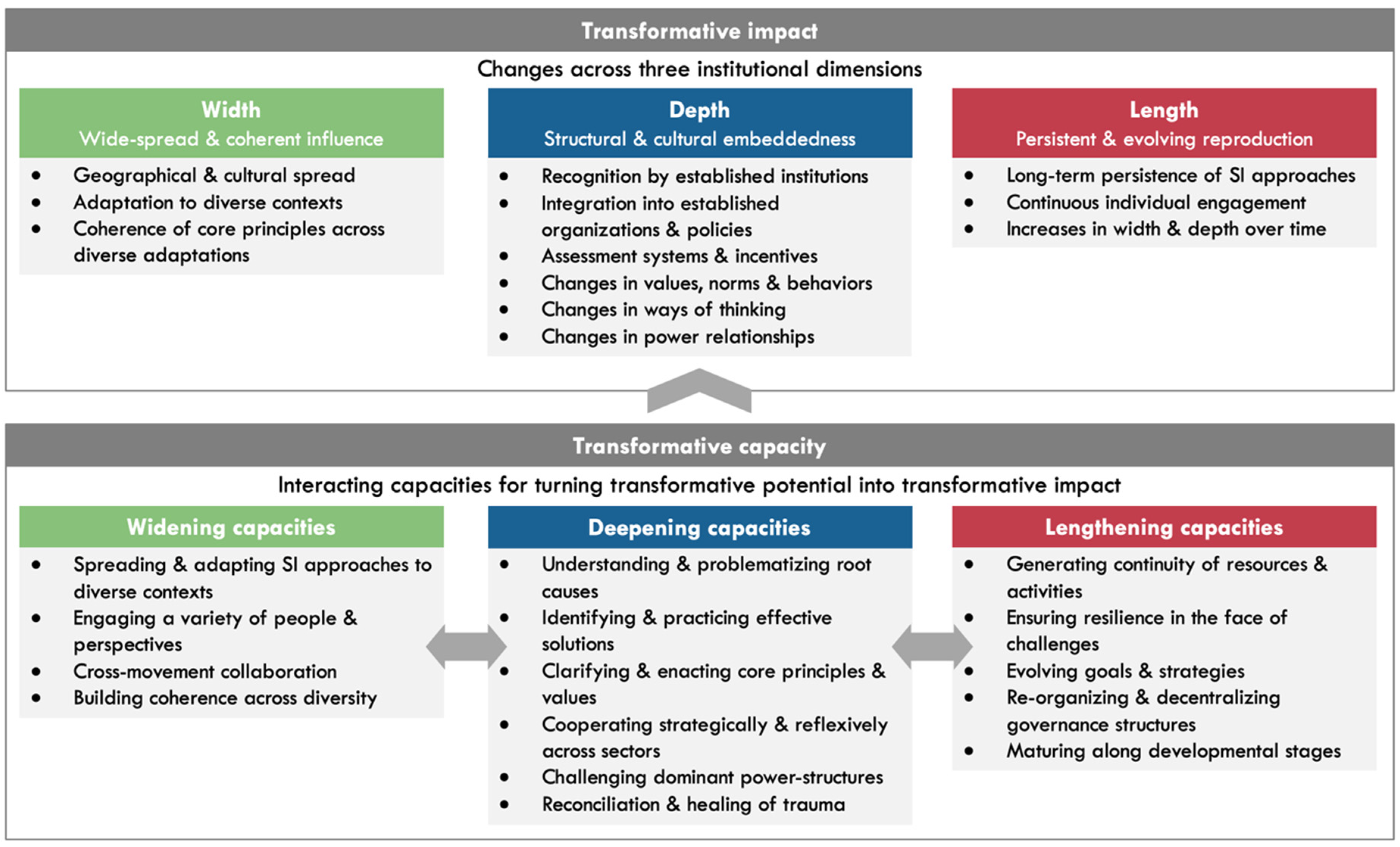

In response to our first research question, we examined how transformative impact and capacity of social innovation networks can be identified and assessed, using a framework of three institutional dimensions: depth, width, and length. We applied and tested this 3D framework by identifying empirical examples to substantiate each of the framework elements, using diagnostic questions (

Appendix B) that were developed based on the original framework. As the original types of transformative impacts were described rather generically, the examples we found make these more concrete and substantiate general themes in different case contexts. During the application it became clear that some of the original types of transformative capacities needed to be refined or complemented (as explained in the results section), to make them more concrete and representative of the empirical data we found.

While transformative capacities were so far described separately for each dimension, they were found to be highly inter-related in practice. We therefore also collected and coded data according to interactions among the three dimensions, which we present in

Appendix D. As identifying interactions was not our main focus, these were, however, not studied in much detail. Hence, we only described them as general statements that could be derived from our data in a rather speculative way. More research would be required to substantiate these interactions in more detail, test their validity in various case contexts, and pay closer attention to synergies and tensions. See

Figure 3 for the revised version of our original 3D framework [

16] (see

Figure 2 in

Section 2), including the concretized elements and an indication of the interaction among capacities.

The results confirm that the 3D framework can be used for assessment purposes, while also indicating that it needs further development in this regard. The examples include general descriptions of the degree to which depth, width, and length impacts have been achieved and the extent to which capacities are more or less developed. However, the focus of this study was not to conduct a detailed and rigorous impact assessment. Rather, we sought to first test and evaluate whether the framework elements are indeed appropriate issues to focus on for an assessment and how they could be used for assessment purposes. It became clear in the application process and from practitioner feedback that a formal impact assessment would require the following further developments of the framework and the diagnostic questions (

Appendix B) that were used in this study.

Firstly, developing more case-specific qualitative as well as quantitative indicators is needed to specify what to assess. As the framework elements are rather generic, indicators need to refer to specific social relations and related ways of doing, organizing, framing, and knowing (DOFK) that characterize a particular social innovation. This can be a challenging task, as units of analysis (i.e., what exactly to assess) are far from self-evident in the complex field of social innovation [

22]. The process of developing case-specific indicators for the GO Movement (see

Appendix C) and GEN and ECOLISE required (gaining) an in-depth understanding of the goals and issues specific to their case contexts.

Secondly, the definition of a clear assessment scope is required: that is, whether the ambition is to assess specific interventions (a program, event, etc.), a geographic focus region of a network, a network as a whole, or even an entire SI field, involving multiple networks and variations of related social innovations. A larger scope would require more capacity for conducting such an assessment.

Thirdly, the existing framework elements did not yet allow for assessing degrees of impacts achieved in a rigorous way. This would require the development of rubrics, ranging from lower to higher degrees of impacts for each dimension, with clear designation for each degree (i.e., on a Likert scale from one to five). We also found that it is important to differentiate between assessing the degree to which depth impacts occurred and the degree of depth of those changes. For instance, while Green Offices have achieved structural integration of sustainability in policies related to sustainable mobility or recycling, these changes are arguably not very transformative in terms of challenging underlying worldviews of the higher education system. Existing frameworks can be helpful to distinguish these degrees further, such as the leverage points framework of Meadows [

74], or the distinction between incremental, reformative, and transformative change by Waddell [

20,

75].

While a comparative analysis across cases was beyond the scope of this study, the 3D framework could be used for this purpose. Some overall differences can be observed between the cases. Green Offices are more structurally embedded, as they are integrated in universities; yet the kind of change promoted is mostly not (yet) very transformative: many focus on reducing the ecological footprint and emissions and giving more voice to students, more than challenging higher education and the socio-economic system at a deeper level. By comparison, oikos chapters are less structurally embedded than Green Offices; however, they promote deeper kinds of changes, by focusing on transforming economics and management education and promoting values-based leadership development, and sustainable finance. Ecovillages and Transition initiatives are generally less structurally embedded (with some exceptions of highly supportive governmental institutions), but more globally spread than the student-led sustainability cases. They also offer deeper solutions in terms of lived alternatives to a materialistic, individualistic, growth-based economy. Mi Sangre and Resonance Network promote deep cultural and systemic changes, though in a more geographically limited scope. Overall, the examples of transformative impact found in this study might be seen as still rather insignificant, considering the high degree of embeddedness, spread, and persistence of dominant institutions. Yet, they can also be regarded as examples of a multitude of TSI actors that are growing in recent years and may become more collectively transformative in the future [

13], if they are able to deepen, widen, and lengthen their impacts. A more rigorous case comparison would require more detailed assessment of each case (see previous paragraphs). A challenge here could be that the indicators and rubrics used for assessing cases would need to be generic enough for meaningful cross-case comparison, yet also specific enough to be pertinent to unique case contexts. Possible avenues for finding such a balance between particularism and generalization include Qualitative Comparative Analysis [

76] and multiplicity-oriented approaches [

22,

77].

In response to our second research question, we tested the recognizability and usefulness of the 3D framework in practice. In particular, drawing on practice experience and active engagement with cases helped to evaluate and strengthen the practical value of this framework. The 3D framework was generally perceived as meaningful and valuable for practitioners in social innovation networks. The conceptualization of specific elements of transformative impact and related capacities was seen as valuable, since identifying, assessing, and developing such capacities is a key priority for all cases. Compared to the frameworks and tools practitioners already use, having a conceptual language that focuses specifically on transformative change was considered as a valuable contribution. Also, most of the networks studied employ principle-based tools to assess, evaluate, and support capacity development of local initiatives (e.g., Transition Network’s healthcheck, or GEN’s Impact Assessment tool). While their tools are often based on essential conditions for local groups to be effective, they miss similar approaches that focus on the level of a network or movement as a whole. The 3D framework offers a comparable function for social innovation networks, more than local groups. The diagnostic questions and empirical examples we found can guide practitioners to be more reflective, strategic, and intentional in their efforts. The generally encouraging responses of practitioners speak to the potential of the framework to be further developed and more widely applied and tested in practice.

Our results contribute to the scientific literature on transformative social innovation and societal transitions [

13,

23] in the following ways. In comparison to other typologies (see Loorbach [

13]), we suggest (and tested in this study) that the three dimensions framework offers comprehensive, yet conceptually simple and intuitive meta categories to identify transformative impact and the capacities required to realize it. It also integrates the length dimension, which is missing or less explicit in other conceptualizations that are more focused on the width and depth dimensions. Transformative impacts and capacities of social innovation so far have not been described in detail in TSI theory and lack specificity in SI research more generally. Our results show how the 3D framework can be used to operationalize general notions about depth, scale, and persistence. The diagnostic questions and examples provided in this study can inform research efforts to identify, assess, and evaluate the impacts and capacities of social innovation networks. Furthermore, by focusing on institutional dimensions, the 3D framework offers a consistent framing of impact across a wide variety of cases in different institutional contexts or SI fields. While other frameworks mostly focus on describing the

dynamics of scaling, trans-local diffusion, and changes in established systems, the 3D framework focuses on

capacities [

21,

25,

26,

27] needed for SI actors to effectively contribute to transformative change. As patterns of effective practice, they therefore also have a prescriptive function for guiding social innovators to act more effectively [

78]. By highlighting the importance of interactions among capacities, we further point to possible synergies and tensions among them (see

Appendix D). This can guide strategic action by strengthening synergies, identifying high leverage interventions [

79], and preventing or addressing possible trade-offs.