Do Women Affect the Final Decision on the Housing Market? A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Basis of the Research

2.1. Historical and Mindset-Based Determinants

2.2. Demographic Factors

2.3. Women as Housing Market Customers

3. Case Study—General Characteristics of the Research Objects

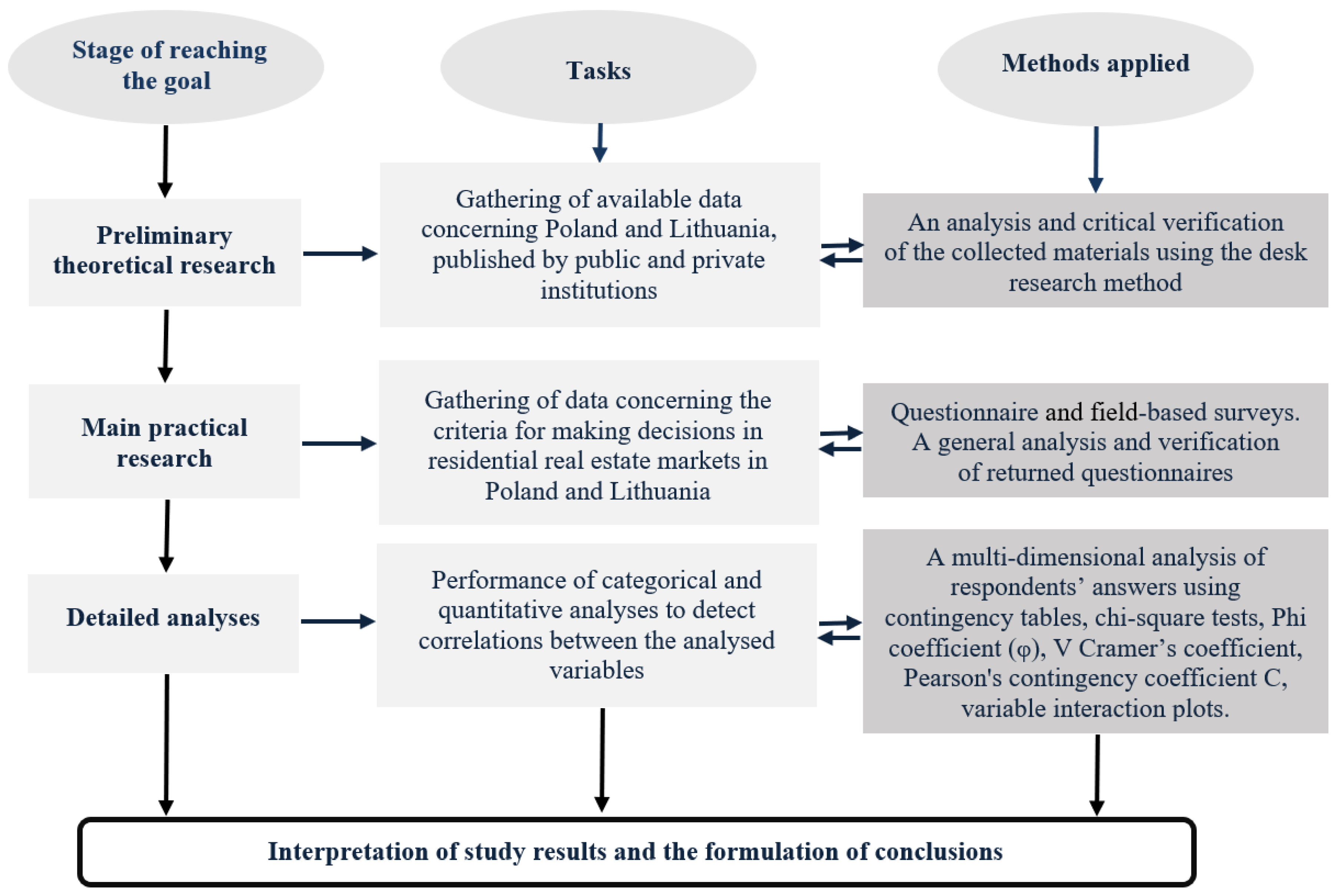

3.1. Description of the Study Structure

3.2. Poland and Lithuania—General Data and a Short Common History

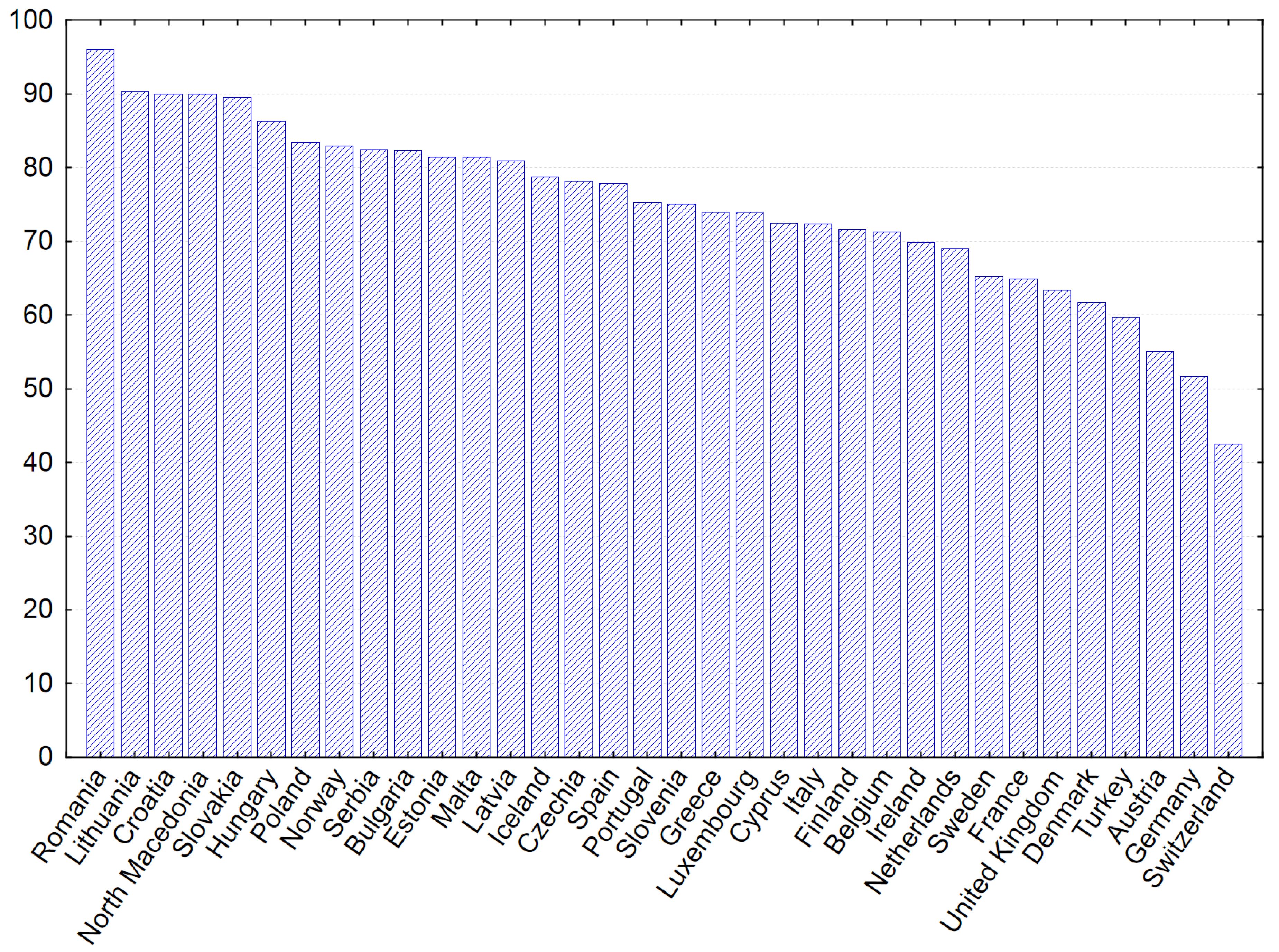

3.3. General Profile of Housing Market Customers

3.4. The Cities Vilnius and Olsztyn as the Objects of Detailed Research

4. Results of the Research and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Olsztyn and Vilnius Respondents

- The willingness to confirm one’s material status (the location in the social hierarchy, defined by the most valuable asset in the household, i.e., a house or a flat);

- The birth of children (the need for increasing the flat’s area);

- Occupational mobility (a choice between tenancy and ownership a flat).

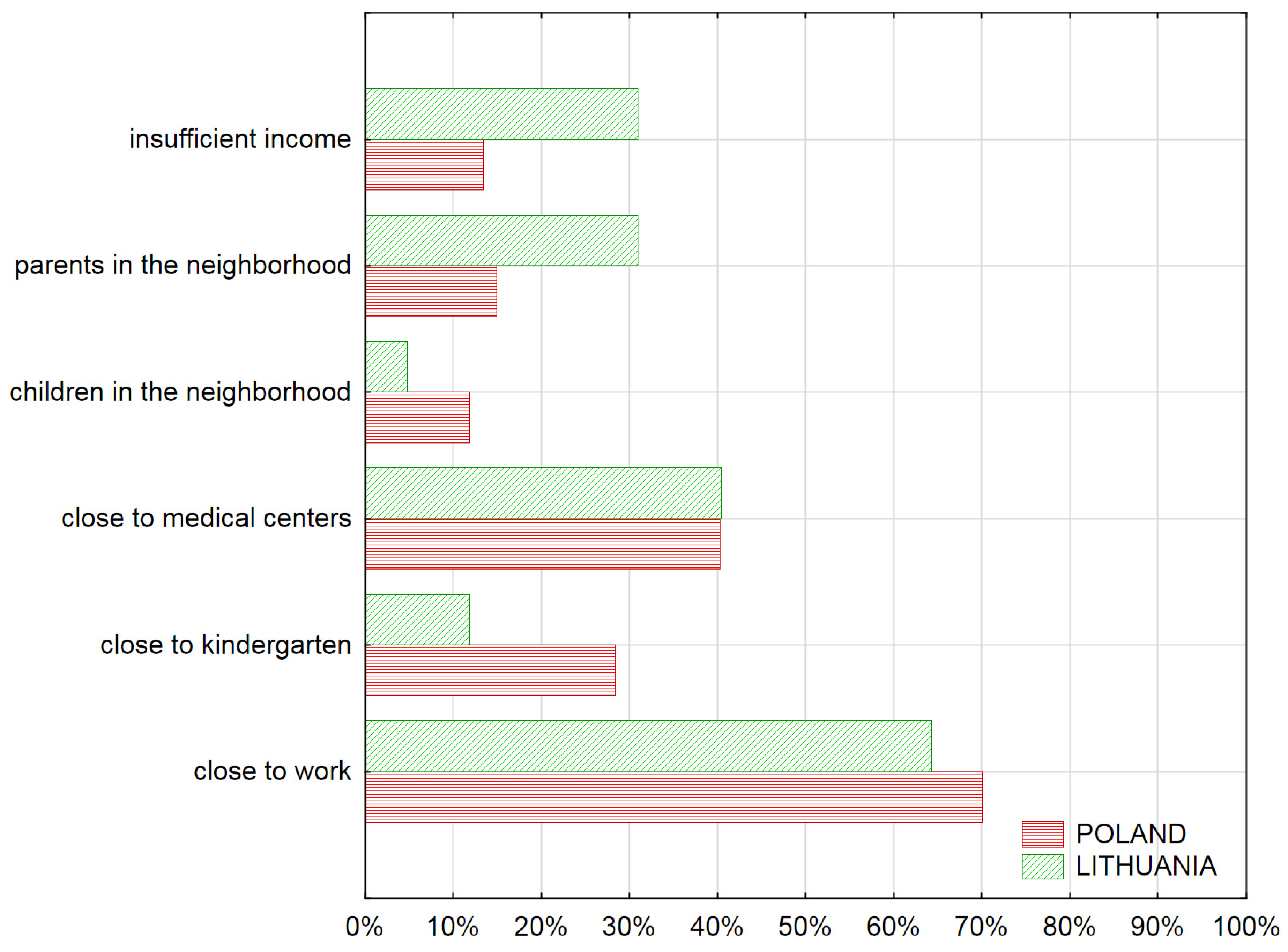

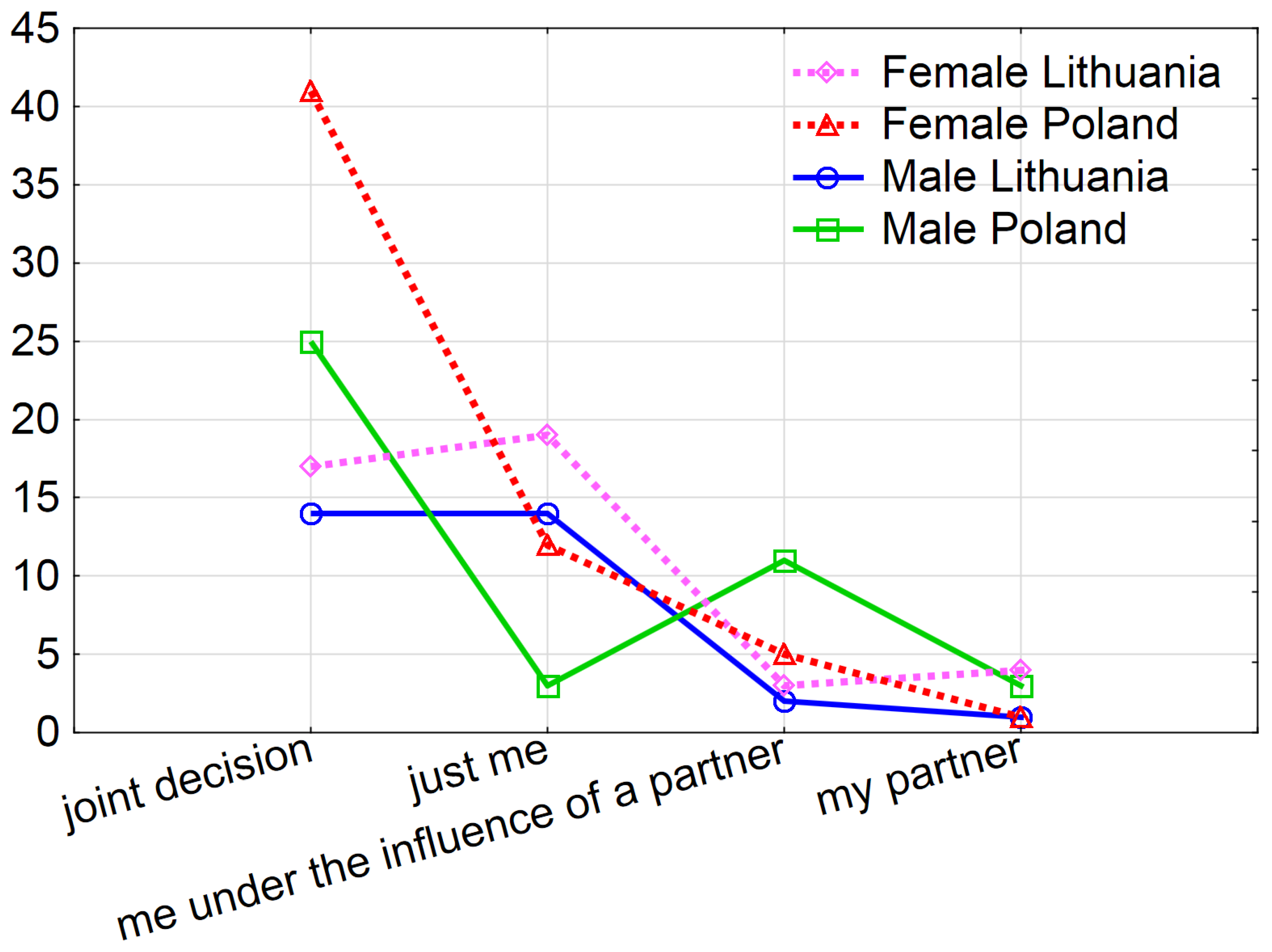

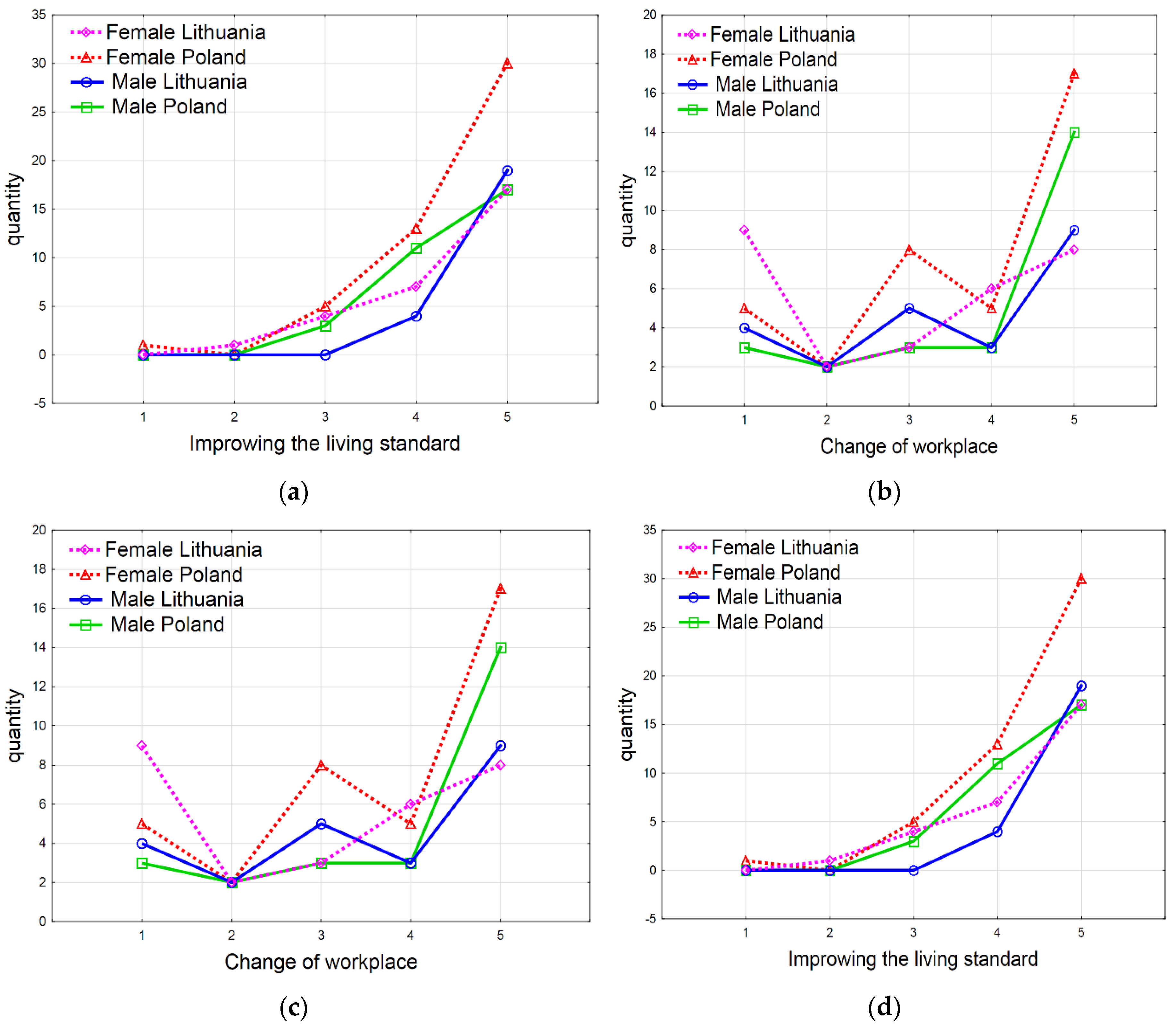

4.2. Examination of Gender Impact on Housing Choice Decisions

- What right do they have to their currently inhabited real estate (ownership/tenancy)?

- Who has had the decisive say as regards the change of flat?

- Whether the next residential real estate will be owned or tenanted.

- The birth of a child: significant (scale—very important, important, moderately important);

- The birth of a child: not important (scale—slightly important, unimportant);

5. Remarks and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- World Health Organization. Housing and Health Guidelines. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/276001/9789241550376-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Case, K.E.; Quigley, J.M.; Shiller, R.J. Comparing Wealth Effects: The Stock Market versus the Housing Market. Adv. Macroecon. 2005, 5, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, P. Wahania Cykliczne Rynków Mieszkaniowych. Aspekty Teoretyczne i Praktyczne; Adam Marszałek: Torun, Poland, 2012; ISBN 978-83-7780-446-9. [Google Scholar]

- Galster, G. William Grigsby and the Analysis of Housing Sub-Markets and Filtering. Urban Stud. 1996, 33, 1797–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykiel, L. Mieszkania Na Wynajem Jako Warunek Rozwoju Rynku Mieszkaniowego. Stud. Mater. Tow. Nauk. Nieruchom. 2012, 20, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Renigier-Biłozor, M.; Biłozor, A.; Wisniewski, R. Rating Engineering of Real Estate Markets as the Condition of Urban Areas Assessment. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopopova, A. Effects of Sheltering on Physiology, Immune Function, Behavior, and the Welfare of Dogs. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 159, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moguerane, K. A Home of One’s Own: Women and Home Ownership in the Borderlands of Post-Apartheid South Africa and Lesotho. Can. J. Afr. Stud. Can. Études Afr. 2018, 52, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museus, S.D.; Yi, V.; Saelua, N. The Impact of Culturally Engaging Campus Environments on Sense of Belonging. Rev. High. Educ. 2017, 40, 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovie, D.A. Assessment of How House Ownership Shapes Health Outcomes in Urban Ghana. Societies 2019, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckie, S. Housing as a Human Right. Environ. Urban. 1989, 1, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojanek, R. Determinanty Wahań Cen Na Rynku Mieszkaniowym. Stud. Mater. Tow. Nauk. Nieruchom. 2008, 16, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Głuszak, M.; Małkowska, A. Preferencje Mieszkaniowe Młodych Najemców Lokali Mieszkalnych w Krakowie. Świat Nieruchom. 2017, 2, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Źróbek-Różańska, A.; Szulc, L. Over a Million Student Tenants in Poland. Analysis of Preferences. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2018, 26, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziworska, K. Rynek Najmu Mieszkań–Współczesne Dylematy. Zarz. Finans. 2017, 15, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- GUS; CSO. Gospodarka Mieszkaniowa w 2016 r. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/infrastruktura-komunalna-nieruchomosci/nieruchomosci-budynki-infrastruktura-komunalna/gospodarka-mieszkaniowa-w-2016-r-,13,12.html (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Statistics Lithuania. Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania (Edition 2019). Available online: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/lietuvos-statistikos-metrastis/lsm-2019/gyventojai-ir-socialine-statistika/bustas (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Himmelberg, C.; Mayer, C.; Sinai, T. Assessing High House Prices: Bubbles, Fundamentals and Misperceptions. J. Econ. Perspect. 2005, 19, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, M.; Tabner, I.T. The Margin of Safety and Turning Points in House Prices: Observations from Three Developed Markets. Financ. Anal. J. 2011, 67, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, A. Posiadanie Własnego Mieszkania a Rodzicielstwo w Polsce. Stud. Demogr. 2011, 1, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, C.H. Home-Ownership and Family Formation. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2006, 21, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoli, D.; Rinesi, F.; Mussino, E. A Home to Plan the First Child? Fertility Intentions and Housing Conditions in Italy. Popul. Space Place 2013, 19, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, K.; Whitehead, C.; Pichler-Milanović, N.; Cirman, A. International Trends in Housing Tenure and Mortgage Finance; London School of Economics: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, H.; Whitehead, C. Housing Tenure and Mortgage Systems: A Survey of Nineteen Countries. In Housing Policy in the United States. An Introduction; Schwartz, A.F., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ineichen, B. The Housing Decisions of Young People. Br. J. Sociol. 1981, 32, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. Portfolio Choices for Homeowners. J. Urban Econ. 2005, 58, 114–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepkova, N.; Butkiene, E.; Bełej, M. Study of Customer Satisfaction with Living Conditions in New Apartment Buildings. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2016, 24, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Źróbek, S.; Trojanek, M.; Źróbek-Sokolnik, A.; Trojanek, R. The Influence of Environmental Factors on Property Buyers’ Choice of Residential Location in Poland. J. Int. Stud. 2015, 7, 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Renigier-Biłozor, M.; Walacik, M.; Źróbek, S.; d’Amato, M. Forced Sale Discount on Property Market—How to Assess It? Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, M.; Smith, S.J. Gender and Housing: Broadening the Debate. Hous. Stud. 1989, 4, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, R.D. Gender, Class and Home Ownership: Placing the Connections. Hous. Stud. 1998, 13, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Ho, Y.-M.; Chiu, H.-Y. Role of Personal Conditions, Housing Properties, Private Loans, and Housing Tenure Choice. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klak, T.H.; Hey, J.K. Gender and State Bias in Jamaican Housing Programs. World Dev. 1992, 20, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, A. Women Heading Households: Some More Equal than Others? World Dev. 1996, 24, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, A. Gender and Property Formalization: Conventional and Alternative Approaches. World Dev. 2007, 35, 1739–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.; Dietrich-Ragon, P.; Bonvalet, C. De Introduction Nouvelles Questions Pour un Vieil Objet. Monde Privé Femmes Genre Habitat Dans Soc. Fr. 2018, 3, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezicka, J.; Wisniewski, R. Znaczenie Płci i Wieku w Procesie Decyzyjnym Na Rynku Nieruchomości. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.J.; Mrosovsky, N. Repeatability of Nesting Preferences in the Hawksbill Sea Turtle, Eretmochelys Imbricata, and Their Fitness Consequences. Anim. Behav. 2005, 70, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Crossley, C.D.; Luthans, F. Psychological Ownership: Theoretical Extensions, Measurement and Relation to Work Outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2009, 30, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pęczak, M. Kupić czy Wynająć Mieszkanie? Available online: http://mdmgdansk.pl/kredyty-i-finansowanie/kupic-czy-wynajac-mieszkanie-co-sie-bardziej-oplaca.html (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Eurostat. Share of Population Living in Owner-Occupied Dwellings in the EU Members. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/4187653/7825811/IMG+graph+1+News+Housing+conditions.png/b0713af5-87dc-4edd-8abc-2a27d5340562?t=1508844372862 (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Megbolugbe, I.F.; Linneman, P.D. Home Ownership. Urban Stud. 1993, 30, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezicka, J.; Wisniewski, R.; Figurska, M. Disequilibrium in the Real Estate Market: Evidence from Poland. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzhynski, S.; Źróbek, S.; Batura, O.; Zysk, E. Why the Market Value of Residential Premises and the Costs of Its Purchase Differ: The Examples of Belarus and Poland. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D.; Sánchez, A.C. Drivers of Homeownership Rates in Selected OECD Countries. OECD Econ. Dep. Work. Pap. 2011, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, R.; Bitetti, R. A Revival of the Private Rental Sector of the Housing Market? Lessons from Germany, Finland, the Czech Republic and the Netherlands. OECD Econ. Dep. Work. Pap. 2014, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarska, M. Kiedy Mieć Dziecko? Jakościowe Badanie Procesu Odraczania Decyzji o Rodzicielstwie. Psychol. Społeczna 2011, 6, 226–240. [Google Scholar]

- GUS; CSO. Ludność. Stan i Struktura Oraz Ruch Naturalny w Przekroju Terytorialnym w 2016 r. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/ludnosc-stan-i-struktura-oraz-ruch-naturalny-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-stan-w-dniu-31-12-2016-r-,6,21.html (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Gyvbudas. Lietuva Pagal Gimdyvių Amžių Vejasi Vakarų Europą. Available online: https://www.lrytas.lt/gyvenimo-budas/seima/2012/09/20/news/lietuva-pagal-gimdyviu-amziu-vejasi-vakaru-europa-5169000/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Foryś, I. Społeczno-Gospodarcze Determinanty Rozwoju Rynku Mieszkaniowego w Polsce: Ujęcie Ilościowe. Rozpr. Stud. Szczec. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- LS, S.L. Mums and dads in Lithuania. Available online: https://osp.stat.gov.lt (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Forlicz, S. Niedoskonała Wiedza Podmiotów Rynkowych; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Charness, G.; Gneezy, U. Strong Evidence for Gender Differences in Risk Taking. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 83, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Jenkins, M. Gender Differences in Risk Assessment: Why Do Women Take Fewer Risks than Men? Judgement Decis. Mak. 2006, 1, 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.M.; Odean, T. Boys Will Be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investment. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 116, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seagraves, P.; Gallimore, P. The Gender Gap in Real Estate Sales: Negotiation Skill or Agent Selection? Real Estate Econ. 2013, 41, 600–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewicz-Tułodziecka, A. Nieruchomość Jako Przedmiot Obrotu i Zabezpieczenia w Polsce. Zesz. Hipoteczne 2008, 27, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Łaszek, J. Kryzysy w Sektorze Nieruchomości, w. Sobiecki R Pietrewicz JW Przedsiębiorstwo Glob. Kryzys SGH; 02-554; SGH Warszawa: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Lithuania. Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 2017. Available online: https://osp.stat.gov.lt (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- KNF. Wyniki Badania Portfela Kredytów Mieszkaniowych i Konsumpcyjnych Gospodarstw Domowych Według Stanu na Koniec 2018 r. Available online: https://www.knf.gov.pl (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Baranowska-Skimina, A. Polskie Kobiety a Rynek Nieruchomości. Available online: http://Www.Nieruchomosci.Egospodarka.Pl/82620,Polskie-Kobiety-a-Rynek-Nieruchomosci,2,79,1.Html (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Nieruchomości. Kobiety na Rynku Nieruchomości: Kupują i Zarządzają. Available online: http://www.nieruchomosci.egospodarka.pl/155037,Kobiety-na-rynku-nieruchomosci kupuja-i-zarzadzaja,1,80,1.html (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- SEB; BL. Annual Report 2017. Available online: https://sebgroup.com/investor-relations/reports-and-presentations/financial-reports/2017/annual-report-2017 (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Maśnica, A. Mieszkania Kupują Najczęściej Kobiety. Available online: https://krakow.wyborcza.pl/krakow/7,44425,23726542,mieszkania-kupuja-najczesciej-kobiety.html?disableRedirects=true (accessed on 17 March 2019).

- Dominium. Mieszkania—Niska Cena to za Mało! Available online: https://www.dominium.pl (accessed on 26 May 2019).

- Walczak, A. Rynek mieszkań: Emeryci Sprzedają, Trzydziestolatki Kupują. 2019. Available online: https://gratka.pl/blog/nieruchomosci/rynek-mieszkan-emeryci-sprzedaja-trzydziestolatki-kupuja/71761/ (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- LB. Lietuvos Bankas-Statistics. Available online: https://www.lb.lt/en/lb-statistics (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Delfi.lt. Lietuviško Investavimo Ypatumai: Vyrams—Bitkoinai, Moterims—Butai Skaitykite Daugiau. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/bustas/nt-rinka/lietuvisko-investavimo-ypatumai-vyrams-bitkoinai-moterims-butai.d?id=77527413 (accessed on 5 May 2019).

- OECD. OECD Guidelines for Micro Statistics on Household Wealth. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264194878-18-en.pdf?expires=1585048675&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=870C4FB3CD297928CE4F6A5EDC3D3136 (accessed on 8 May 2019).

- Levy, D.S.; Lee, C.K.-C. The Influence of Family Members on Housing Purchase Decisions. J. Prop. Invest. Finance 2004, 22, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telyukova, I.; Nakajima, M. Home Equity Withdrawal in Retirement. In 2010 Meeting Papers; Society for Economic Dynamics: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cocco, J.F.; Gomes, F.J.; Maenhout, P.J. Consumption and Portfolio Choice over the Life Cycle. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2005, 18, 491–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogo, M. Portfolio Choice in Retirement: Health Risk and the Demand for Annuities, Housing, and Risky Assets. J. Monet. Econ. 2016, 80, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, V.; Brugiavini, A.; Weber, G. The Dynamics of Homeownership among the 50+ in Europe. J. Popul. Econ. 2014, 27, 797–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatfield, C.; Collins, A. Introduction to Multivariate Analysis; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1, p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- Łapczyński, M. Analiza Porównawcza Tabel Kontyngencji i Metody CHAID. Zesz. Nauk. Ekon. W Krakowie 2005, 659, 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sagan, A. Asymetryczne Metody Wielowymiarowe w Badaniach Marketingowych. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2011, 236, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin, R.C.; Seaman, M.A. Log-Linear Analysis. In The Reviewer’s Guide to Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Molenberghs, G. Multivariate Statistical Modelling Based on Generalized Linear Models. Biometrics 2001, 57, 1274. [Google Scholar]

- Proto. The Increasing the Potential Client’s Interest. Available online: https://www.proto.pl (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Kalinowska-Sołtys, A. Zrównoważony Czyli Jaki? Available online: https://builderpolska.pl/2020/03/04/builder-marzec-2020/ (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Global Compact Network Poland, Zrównoważone Miasta. Poprawa Jakości Powietrza w Polsce 2018. Available online: https://ungc.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Zrównoważone-Miasta.-Poprawa-jakości-powietrza-w-Polsce-2018.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Pałucha, K. Współpraca Przedsiębiorstw w Procesie Budowania Ich Potencjału Innowacyjnego. Zesz. Nauk. Organ. Zarządzanie Politech. Śląska 2016, 93, 393–403. [Google Scholar]

| Kinds of Data | Poland (PL) | Lithuania (LT) |

|---|---|---|

| General location and area | Europe/312,679 sq. km | Europe/65,300 sq. km |

| Government | Parliamentary Republic | Unitary semi-presidential republic |

| Member of the European Union | From 1 May 2004 | From 1 May 2004 |

| Population | 38,432,992 | 2,791,903 |

| Age structure of the population | ||

| 0–14 years | 15.0% | 15.8% |

| 15–64 years | 68.6% | 61.8% |

| 65 years and more | 16.4% | 22.4% |

| Women as % of the population | 52% | 53.9% |

| The average size of flats | 73.8 m2 in urban areas—64.5 m2, in rural areas—93.1m2 | 68 m2 in urban areas—62.1 m2, in rural areas—79.9 m2. |

| Gross domestic product, current prices in USD Billion Dollars | GDP 571.32 | GDP 96.91 |

| Gross domestic product per capita, current prices in USD | GDP per capita 13,811.66 USD | GDP per capita 16,680.68 USD |

| Unemployment rate | 4.5% | 6.1% |

| Sources of Data | Type of Data | Polish Client | Lithuanian Client |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bank statistical analyses | Age of borrowers | Up to 35 years (57.6% share in the number of mortgage loans). | 25–34 years (60% share in the number of mortgage loans). |

| Aim of a mortgage | Flat purchase (66%) | Flat purchase (58%) | |

| Direct interview— bank advisers | Gender of person signing the loan agreement | Joint ownership of statutory marriage—together. Single people—more often men; women very rarely. | Married couple—together. Single—more often men |

| Direct interview— real estate agents | Gender of person signing an agency contract | 53% women | 45% women |

| Gender of person having a decisive voice in the selection of real estate | 90% women | 45% women | |

| Gender of person looking for real estate | 47% women | 45% women | |

| What right to real estate is acquired? | 54% women indicated the ownership of real estate. | 40% of women indicated the ownership of real estate. | |

| Stage of life | Young spouses make a decision together. Mature families—the wife makes the decision (men older than 40 years are more involved in work outside the home). | Young spouses make a decision together. |

| Data Types | Olsztyn | Vilnius |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of inhabitants, including: | 173,000 | 551,900 |

| women | 53.5% | 55% |

| men | 46.5% | 45% |

| Households | ||

| multi-person households | 62% | 64% |

| one-person households | 38% | 36% |

| Age structure of the population at the: | ||

| pre-working age | 17% | 16% |

| working age | 61% | 67% |

| post-working age (retirees) | 22% | 17% |

| Gross monthly income/price of 1 m2 of a flat | 0.94 | 0.83 |

| Gross monthly income/monthly rent for a 45 m2 of a flat | 2.33 | 3.06 |

| Feature | Characteristic | Olsztyn | Vilnius |

|---|---|---|---|

| Households | Multi-person household | 79.2% | 57.1% |

| One-person household | 20.8% | 42.9% | |

| Sex | Female | 58.4% | 61.9% |

| Male | 41.6% | 38.1% | |

| Age (in years) | <30 | 9.9% | 41.7% |

| 31–45 | 65.2% | 33.3% | |

| 46–60 | 11% | 22.6% | |

| 61< | 13.9% | 2.4% | |

| Employment | |||

| State sector | 58.4% | 31.0% | |

| Private sector | 15.8% | 50.0% | |

| Own business | 14.9% | 8.3% | |

| Unemployed | 2.0% | 8.3% | |

| Retirement | 8.9% | 2.4% | |

| Place of residence | Voivodeship city | 57.4% | 95.2% |

| County city | 25.8% | 3.6% | |

| Community | 6.9% | 0.0% | |

| Village | 9.9% | 1.2% | |

| Satisfaction with the current place of residence | |||

| Definitely like | 43.4% | 40.5% | |

| Like | 22.2% | 19.0% | |

| Rather like | 18.2% | 9.5% | |

| Want to change | 16.2% | 31.0% |

| No. | Relation | Statistical Measure | Chi-Square Test | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Gender–current property rights (ownership/tenancy) | Pearson’s Chi-square test | 17.27 | df = 3 | p = 0.00062 |

| Pearson’s Chi-square highest credibility test | 17.83 | df = 3 | p = 0.00048 | ||

| Phi coefficient | 0.31 | ||||

| Cramer’s V factor | 0.31 | ||||

| Pearson’s C contingency coefficient | 0.29 | ||||

| II | Gender–decision-maker on the change of a flat | Pearson’s Chi-square test Pearson’s Chi-square highest credibility test Phi coefficient Cramer’s V factor Pearson’s C contingency coefficient | 32.88 33.23 0.43 0.25 0.38 | df = 9 df = 9 | p = 0.00014 p = 0.00012 |

| III | Gender–type of right (ownership/tenancy) when changing a flat | Pearson’s Chi-square test Pearson’s Chi-square highest credibility test Phi coefficient Cramer’s V factor Pearson’s C contingency coefficient | 0.22 0.21 0.05 0.05 0.05 | df = 3 df = 3 | p = 0.97469 p = 0.97557 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Źróbek, S.; Zysk, E.; Bełej, M.; Lepkova, N. Do Women Affect the Final Decision on the Housing Market? A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4652. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114652

Źróbek S, Zysk E, Bełej M, Lepkova N. Do Women Affect the Final Decision on the Housing Market? A Case Study. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4652. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114652

Chicago/Turabian StyleŹróbek, Sabina, Elżbieta Zysk, Mirosław Bełej, and Natalija Lepkova. 2020. "Do Women Affect the Final Decision on the Housing Market? A Case Study" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4652. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114652

APA StyleŹróbek, S., Zysk, E., Bełej, M., & Lepkova, N. (2020). Do Women Affect the Final Decision on the Housing Market? A Case Study. Sustainability, 12(11), 4652. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114652