Relationship between Viewing Motivation, Presence, Viewing Satisfaction, and Attitude toward Tourism Destinations Based on TV Travel Reality Variety Programs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Viewing Motivation for Travel Reality Variety Programs

2.2. Presence

2.3. Viewing Satisfaction

2.4. Attitude toward Tourism Destinations

3. Research Model and Methodology

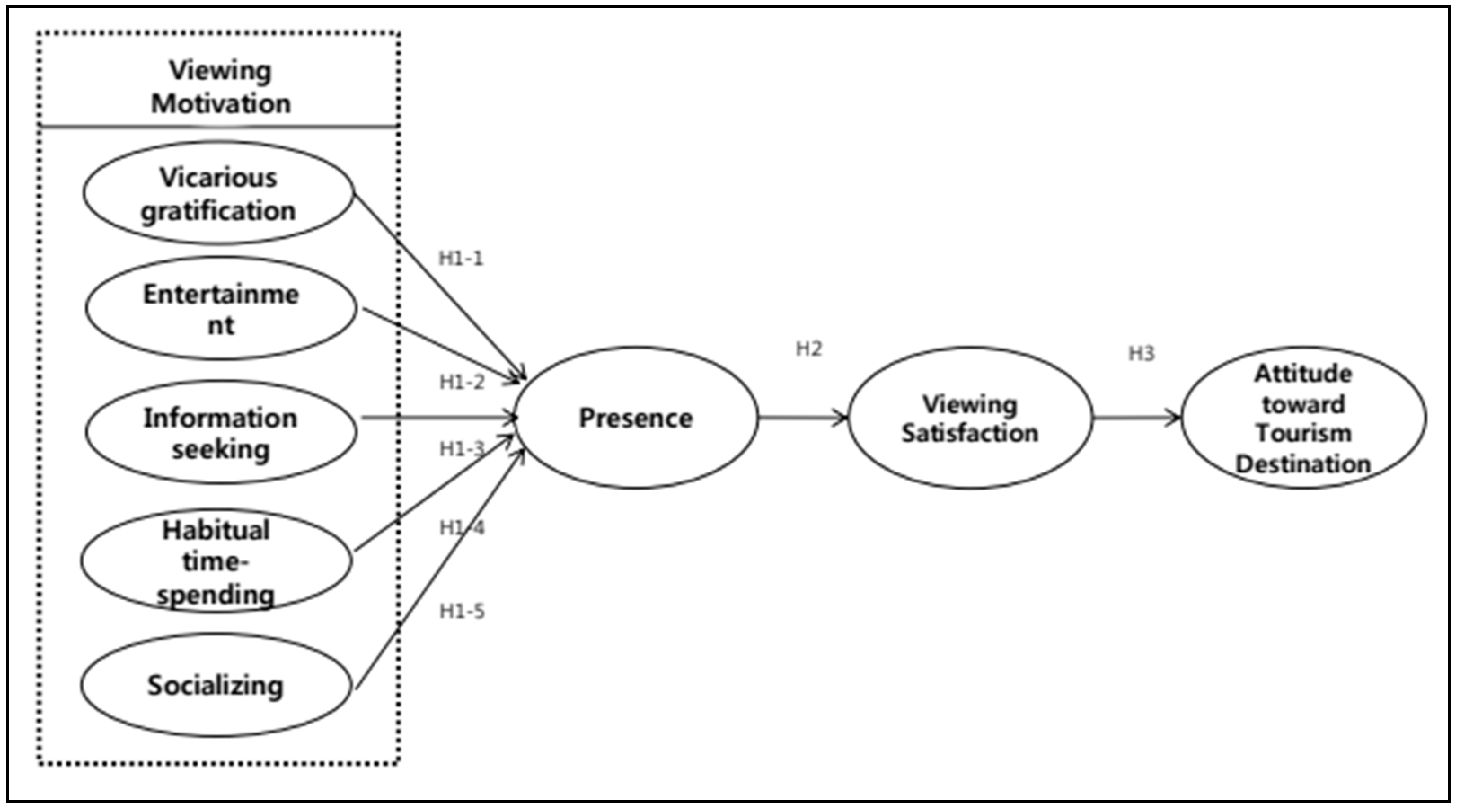

3.1. Research Model and Hypotheses Development

3.2. Operational Definition

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis Method

4. Results

4.1. Profile of the Sample

4.2. Reliability and Validity

4.3. Verification of Hypotheses

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shah Alam, S.; Mohamed Sayuti, N. Applying the theory of planned behavior (TPB) in halal food purchasing. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2011, 21, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharissi, Z.; Mendelson, A.L. An exploratory study of reality appeal: Uses and gratifications of reality TV Shows. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2007, 51, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Ye, B.H.; Xiang, J. Reality TV audience travel intentions, and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.O.; Kim, N.J. A study on the perception of elderly leisure of the reality program ‘Grandpa over Flowers’ older generation viewers: Focusing on the middle class. J. Tour. Sci. 2016, 40, 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Rubin, A.M. The variable influence of audience activity on media effects. Commun. Res. 1997, 24, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G.; Dubelaar, C. A general theory of tourism consumption systems: A conceptual framework and an empirical exploration. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.S.; Shin, K.H. The effects of reality programming in the selection of tour destinations for foreign travelers: Focused on the show ‘grandpa rather than flowers’ (Taiwan). Northeast Asia Tour. Res. 2016, 12, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, T.; Leets, L. Attachment styles and intimate television viewing: Insecurely forming relationships in a parasocial way. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1999, 16, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G.; Gurevitch, M. Utilization of mass communication by the individual. In The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspective on Gratifications Research; Blumler, J.G., Katz, E., Eds.; Sage Kayak: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, S.H.; Park, S.B. Rethinking of TV viewing Satisfaction: Relationships among TV viewing Motivation, Parasocial Interaction, and Presence. Korean J. Broadcast. Telecommun. Stud. 2007, 21, 339–379. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, L.; Latimer, L.; Wansink, B. Viewers vs. doers. The relationship between watching food television and BMI. Appetite 2015, 90, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.K.; Yhang, W.J. The Effect of Tourism Destination Placement Types in Real Variety Program on Indirect Experience and Attidute: By the Moderating Effect of Parasocial Interaction. Ph.D. Thesis, Pukyong National University, Busan, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.W. The effects of the experience of Korean Wave contents and Korean product and services on preference for the Korean Wave, Change in Korea awareness and behavior intention: Focusing on China, Japan and USA. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2019, 32, 2107–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J. A Study on the uses and gratifications on the U. S. TV dramas: Focusing on comparison to the Korean counterparts. Korean J. Commun. Inf. 2008, 41, 302–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, O.S.; Park, J.Y. A Study on motivations and effects of viewing reality date programs: Focusing on < The Partner > on SBS. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev. Kyunhsung Univ. 2014, 29, 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.Y.; Han, J.S. A study on the influence of viewing motivation of a TV reality travel program on viewing satisfaction and visit intention: Moderating effect of travel involvement. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 32, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, J.A.; Cho, S.H. Motivations and gratifications of re-watchng terrestrial broadcasting programs. Korean Reg. Commun. Res. Assoc. 2013, 14, 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.M. Presence, explicated. Commun. Theory 2004, 14, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biocca, F. The cyborg’s dilemma: Progressive embodiment in virtual environments. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 1997, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, R.; Woodside, A.G. Testing theory of planned versus realized tourism behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 905–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessitore, T.; Pandelaere, M.; Van Kerckhove, A. The amazing race to India: Prominence in reality television affects destination image and travel intentions. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Ditton, T. At the heart of it all: The concept of presence. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 1997, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, C. Presence and image quality: The case of high-definition television. Media Psychol. 2009, 7, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E. Mass communications research and the study of popular culture: An editorial note on a possible future for this journal. Stud. Public Commun. 1959, 2, 1–6. Available online: http://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Godlewski, L.R.; Perse, E.M. Audience Activity and Reality Television: Identification, Online Activity, and Satisfaction. Commun. Q. 2010, 58, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.V.; Arulchelvan, S. Motivation and impact of viewing reality Television programme: An audience study. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Palmgreen, P.; Rayburn, J.D. Merging uses and gratifications and expectancy-value theory. Commun. Res. 1984, 11, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, B.J.; Kim, M.G.; Lee, C.H. The effect of TV viewers’ perceived similarity, wishful identification, and para-social interaction on tourism Attitude: In the case of a travel-reality show. Tour. Res. Inst. Hanyang Univ. 2018, 1, 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bettinghaus, E.P.; Cody, M.J. Persuasive Communication; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief. Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research Reading; Addison-Wesley: Amherst, MA, USA, 1975; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrig, R.J.; Zimbardo, P.G.; Campbell, A.J.; Cumming, S.R.; Wilkes, F.J. Psychology and Life; Pearson Higher Education AU: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The advantages of an inclusive definition of ttitude. Soc. Cogn. 2007, 25, 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.K. Extending the theory of planned behavior: Visa exemptions and the traveler decision-making process. Tour. Geogr. 2011, 13, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuail, D. Audience formation and experience. In Mass Communication Theory, 5th ed.; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 419–452. [Google Scholar]

- Steuer, J. Defining virtual reality: Dimensions determining terepresence. J. Commun. 1992, 42, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Israeli, A.A.; Mehrez, A. Modelling a decision maker’s preferences with different assumptions about the preference structure. Tour. Econ. 2002, 8, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.E.; Kang, C.H. The effect of tourist attraction exposure in a TV program on the tourist Volume: The case of tvN “Over Flowers” Series. Korean Assoc. Appl. Econ. 2018, 20, 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, B. Film-induced tourism in Asia: A case study of Korean television drama and female viewers’ motivation to visit Korea. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2007, 7, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, C.; Ditton, T.B. Presence and television: The role of screen size. Hum. Commun. Res. 2000, 26, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H. Theory of planned behavior: Potential travelers from China. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2004, 28, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebersole, S.; Woods, R. Motivations for viewing reality Television: A uses and gratifications analysis. Southwest Mass Commun. J. 2007, 23, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, M.R. Need for interaction or Pursuit of information and entertainment? The relationship among viewing motivation, presence, parasocial interaction, and satisfaction of eating and cooking broadcasts. Korean J. Broadcast. Telecommun. Stud. 2016, 30, 152–185. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, J.R.; Murphy, T.H. Handling nonresponse in social science research. J. Agric. Educ. 2001, 42, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.W.; Lee, Y.J. The impact of watching motives of parenting reality TV program on user satisfaction and rewatching. J. Broadcast Eng. 2014, 19, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.E.; Choi, H.S. A Study on the Effect of Entertainment Show on the Tourism. Korea Contents Soc. 2016, 215–216. [Google Scholar]

- Quintal, V.A.; Lee, J.A.; Soutar, G.N. Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A tourism example. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y. Prospects for Korea Tourism trend 2020-2024. Korea Tour. Policy 2019, 78, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

| Classification | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Classification | Frequency | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 188 | 52.7 | Amount of travel in a year | 1 time | 119 | 33.5 |

| Female | 170 | 47.3 | 2–3 times | 142 | 39.7 | ||

| Age (years) | 20 | 103 | 29.0 | 4–5 times | 38 | 10.7 | |

| 30 | 113 | 31.7 | 6–7 times | 17 | 4.9 | ||

| 40 | 88 | 24.6 | >8 times | 42 | 11.2 | ||

| 50 | 38 | 10.7 | Number of reality variety programs watched in a week | 1 time | 54 | 14.7 | |

| >60 | 16 | 4.0 | 2–3 times | 177 | 49.6 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 230 | 64.5 | 4–5 times | 76 | 21.4 | |

| Single | 128 | 35.5 | 6–7 times | 51 | 14.3 | ||

| Occupation | Homemaker | 51 | 14.3 | Monthly income (in million won) | <1.49 | 36 | 10.1 |

| Specialized job | 84 | 23.7 | 1.5–2.99 | 48 | 13.5 | ||

| Office worker | 193 | 54.0 | 3–4.99 | 198 | 55.4 | ||

| Other | 30 | 8.0 | >5 | 76 | 21.0 | ||

| Sum | 358 | 100 | Sum | 358 | 100 | ||

| Construct | Measurement Items | Factor Loading | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | Cronbach’s a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vicarious gratification | While watching reality travel variety programs, I feel assimilated with the characters. | 0.728 | 0.902 | |||

| While watching reality travel variety programs, I can forget my daily life. | 0.755 | 0.074 | 13.918 | <0.001 | ||

| While watching reality travel variety programs, I feel as though I am in the village. | 0.842 | 0.077 | 15.547 | <0.001 | ||

| While watching reality travel variety programs, I feel like a resident of the village. | 0.854 | 0.081 | 15.765 | <0.001 | ||

| While watching reality travel variety programs, I feel like I am traveling. | 0.840 | 0.082 | 15.513 | <0.001 | ||

| Entertainment | Reality travel variety programs are more entertaining than other reality variety programs. | 0.701 | 0.846 | |||

| Viewing reality travel variety programs makes me happy. | 0.824 | 0.066 | 14.348 | <0.001 | ||

| Every new episode of a reality travel variety program is interesting. | 0.873 | 0.069 | 15.061 | <0.001 | ||

| Places that appear in reality travel variety programs are more interesting than in other reality variety programs. | 0.780 | 0.075 | 13.637 | <0.001 | ||

| Information-seeking | Reality travel variety programs show specific information about tourism destinations. | 0.758 | 0.863 | |||

| Reality travel variety programs show cultural information about tourism destinations. | 0.652 | 0.068 | 12.254 | <0.001 | ||

| Reality travel variety programs are educational in showing the way of life in tourist destinations. | 0.776 | 0.073 | 14.844 | <0.001 | ||

| Reality travel variety programs are beneficial because they provide an overview of tourism destinations. | 0.772 | 0.075 | 14.755 | <0.001 | ||

| Reality travel variety programs have enhanced my intellectual ability to travel by making it possible to know about tourism destinations. | 0.779 | 0.068 | 14.892 | <0.001 | ||

| Habitual time-spending | Reality travel variety programs are good for spending time alone. | 0.820 | 0.899 | |||

| Reality travel variety programs are good to watch without thinking. | 0.827 | 0.056 | 18.046 | <0.001 | ||

| I watch reality travel variety programs habitually without a special purpose. | 0.814 | 0.059 | 17.658 | <0.001 | ||

| There are no other programs to watch at the time this program is broadcast. | 0.863 | 0.056 | 19.176 | <0.001 | ||

| Socializing | I watch reality travel variety programs to empathize with others. | 0.642 | 0.746 | |||

| Reality travel variety program are subjects of interest among people. | 0.557 | 0.134 | 8.753 | <0.001 | ||

| I watch reality travel variety programs to avoid being alienated from conversations with others. | 0.745 | 0.144 | 9.487 | <0.001 | ||

| Viewing satisfaction | I am satisfied with the content of reality travel variety programs. | 0.650 | 0.803 | |||

| I would like to watch more reality travel variety programs. | 0.783 | 0.096 | 12.844 | <0.001 | ||

| I am satisfied that I have gained useful information about places and cultures that appear in reality travel variety programs. | 0.911 | 0.101 | 14.400 | <0.001 | ||

| I would like my acquaintances to recommend watching reality travel variety programs. | 0.907 | 0.103 | 14.349 | <0.001 | ||

| Presence | I feel that I am in the TV situation with the characters. | 0.709 | 0.887 | |||

| I feel that the situations on TV are happening in front of my eyes. | 0.815 | 0.066 | 14.020 | <0.001 | ||

| The characters on the TV seem to be talking right in front of me. | 0.890 | 0.076 | 14.640 | <0.001 | ||

| I feel that I am in that place on the TV. | 0.645 | 0.073 | 11.292 | <0.001 | ||

| Attitude toward tourism destinations | I feel that the places that appear on reality travel variety programs are good. | 0.759 | 0.882 | |||

| I feel that the places that appear on reality travel variety programs are good places to travel. | 0.769 | 0.068 | 14.924 | <0.001 | ||

| I like the places that appear on reality travel variety programs. | 0.847 | 0.068 | 16.637 | <0.001 | ||

| I feel that the places that appear on reality travel variety programs are attractive. | 0.854 | 0.067 | 16.806 | <0.001 | ||

| Χ2 = 982.850, df = 467, p = 0.000, (AGFI = 0.909 TLI = 0.924, CFI- = 0.933, RMSEA = 0.056) | ||||||

| Vicarious Gratification | Entertainment | Information- Seeking | Habitual Time-Spending | Socializing | Viewing Satisfaction | Presence | Attitude toward Tourism Destination | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vicarious Gratification | (0.636) | |||||||

| Entertainment | 0.458 ** | (0.661) | ||||||

| Information-Seeking | 0.457 ** | 0.560 ** | (0.701) | |||||

| Habitual Time-Spending | 0.388 ** | 0.536 ** | 0.722 ** | (0.759) | ||||

| Socializing | 0.452 ** | 0.469 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.364 ** | (0.711) | |||

| Satisfaction | 0.464 ** | 0.528 ** | 0.588 ** | 0.521 ** | 0.593 ** | (0.745) | ||

| Presence | −0.029 | 0.003 | −0.020 | 0.020 | 0.012 | 0.049 | (0.749) | |

| Attitude toward Tourism Destination | 0.417 ** | 0.655 ** | 0.576 ** | 0.538 ** | 0.483 ** | 0.744 ** | 0.043 | (0.758) |

| Structural Paths | β | t-Value | Hypothesis Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1-1 | Vicarious Gratification → Presence | 0.453 | 4.899 *** | Supported |

| H1-2 | Entertainment → Presence | 0.286 | 4.030 *** | Supported |

| H1-3 | Information-Seeking → Presence | 0.131 | 2.182 * | Supported |

| H1-4 | Habitual Time-Spending → Presence | 0.076 | 1.302 | Rejected |

| H1-5 | Socializing → Presence | 0.129 | 1.937 | Rejected |

| H2 | Presence → Viewing Satisfaction | 0.239 | 4.517 *** | Supported |

| H3 | Viewing Satisfaction → Attitude toward Tourism Destination | 0.818 | 10.630 *** | Supported |

| Model fit | Chi-square/df = 958.581/483, CMIN/df = 1.984, RMR = 0.028 GFI = 0.900, AGFI = 0.902, CFI = 0.908, NFI = 0.901, IFI = 0.909, RMSEA = 0.063 | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, B.-K.; Kim, K.-O. Relationship between Viewing Motivation, Presence, Viewing Satisfaction, and Attitude toward Tourism Destinations Based on TV Travel Reality Variety Programs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114614

Kim B-K, Kim K-O. Relationship between Viewing Motivation, Presence, Viewing Satisfaction, and Attitude toward Tourism Destinations Based on TV Travel Reality Variety Programs. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114614

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Bo-Kyeong, and Kyoung-Ok Kim. 2020. "Relationship between Viewing Motivation, Presence, Viewing Satisfaction, and Attitude toward Tourism Destinations Based on TV Travel Reality Variety Programs" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114614

APA StyleKim, B.-K., & Kim, K.-O. (2020). Relationship between Viewing Motivation, Presence, Viewing Satisfaction, and Attitude toward Tourism Destinations Based on TV Travel Reality Variety Programs. Sustainability, 12(11), 4614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114614