An Analysis of the Sustainable Tourism Value of Graffiti Tours through Social Media: Focusing on TripAdvisor Reviews of Graffiti Tours in Bogota, Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction and Research Backgrounds

1.1. Function of Sustainable Tourism

1.2. Graffiti Tour

1.3. Graffiti Tours in Bogota, Colombia

1.4. Value of Sustainability of Graffiti Tours

2. Data and Methods

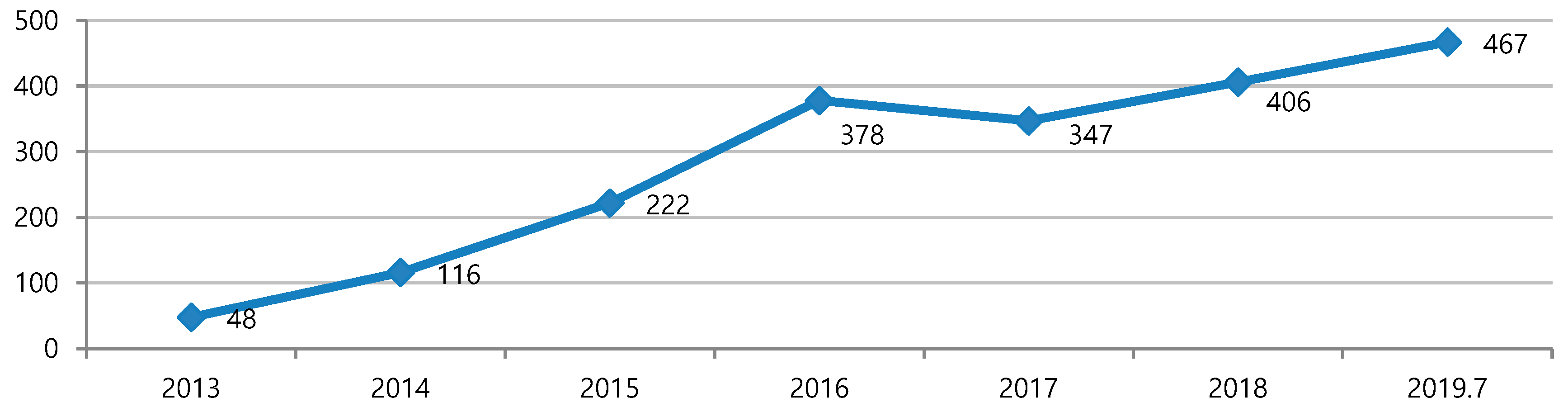

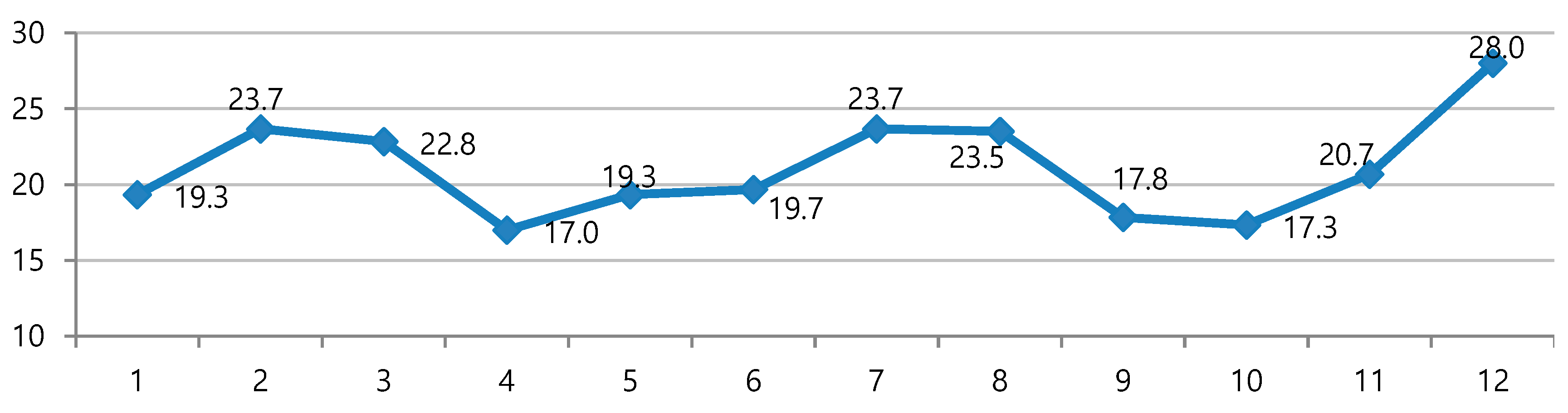

2.1. Data

2.2. Analysis

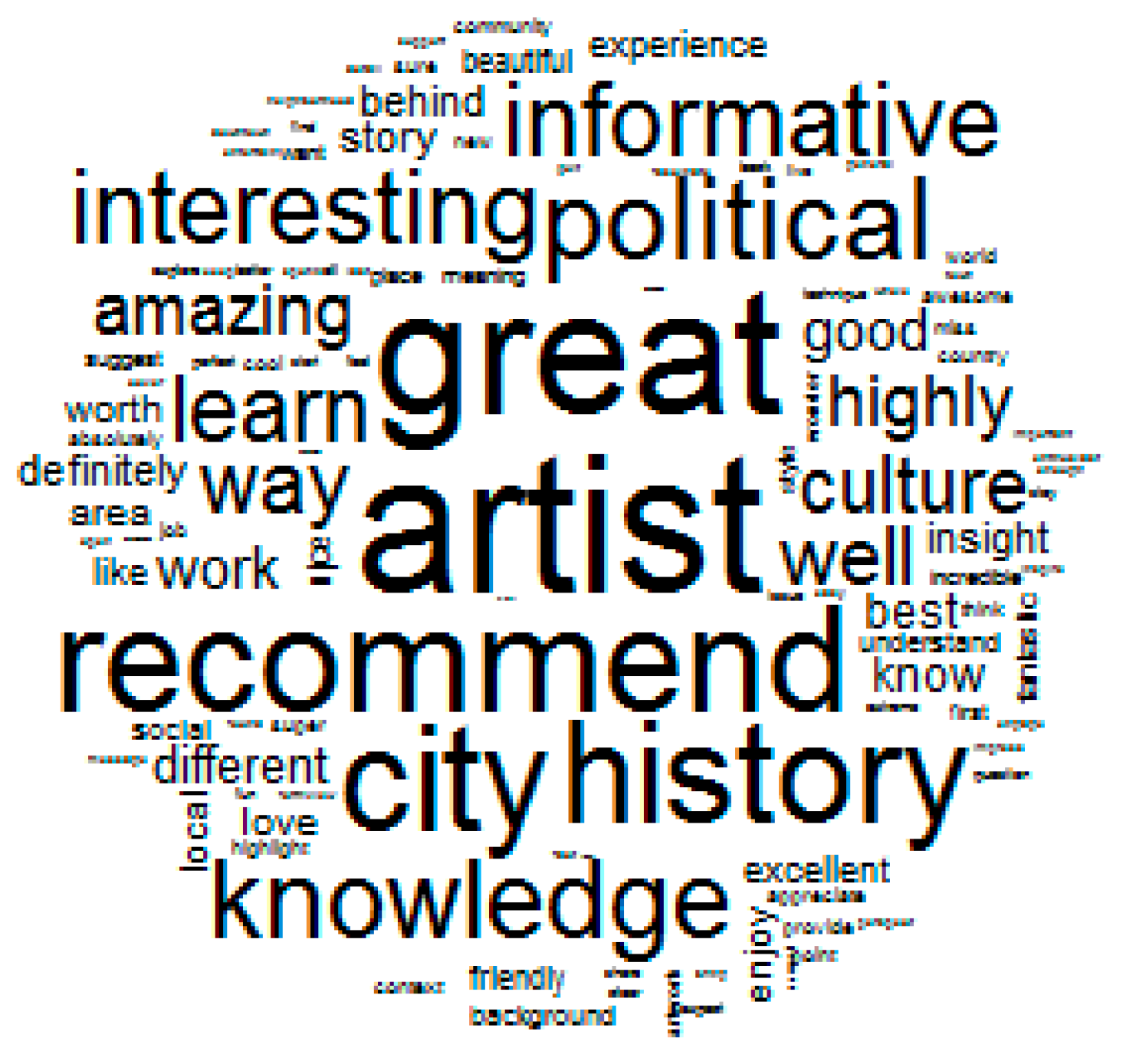

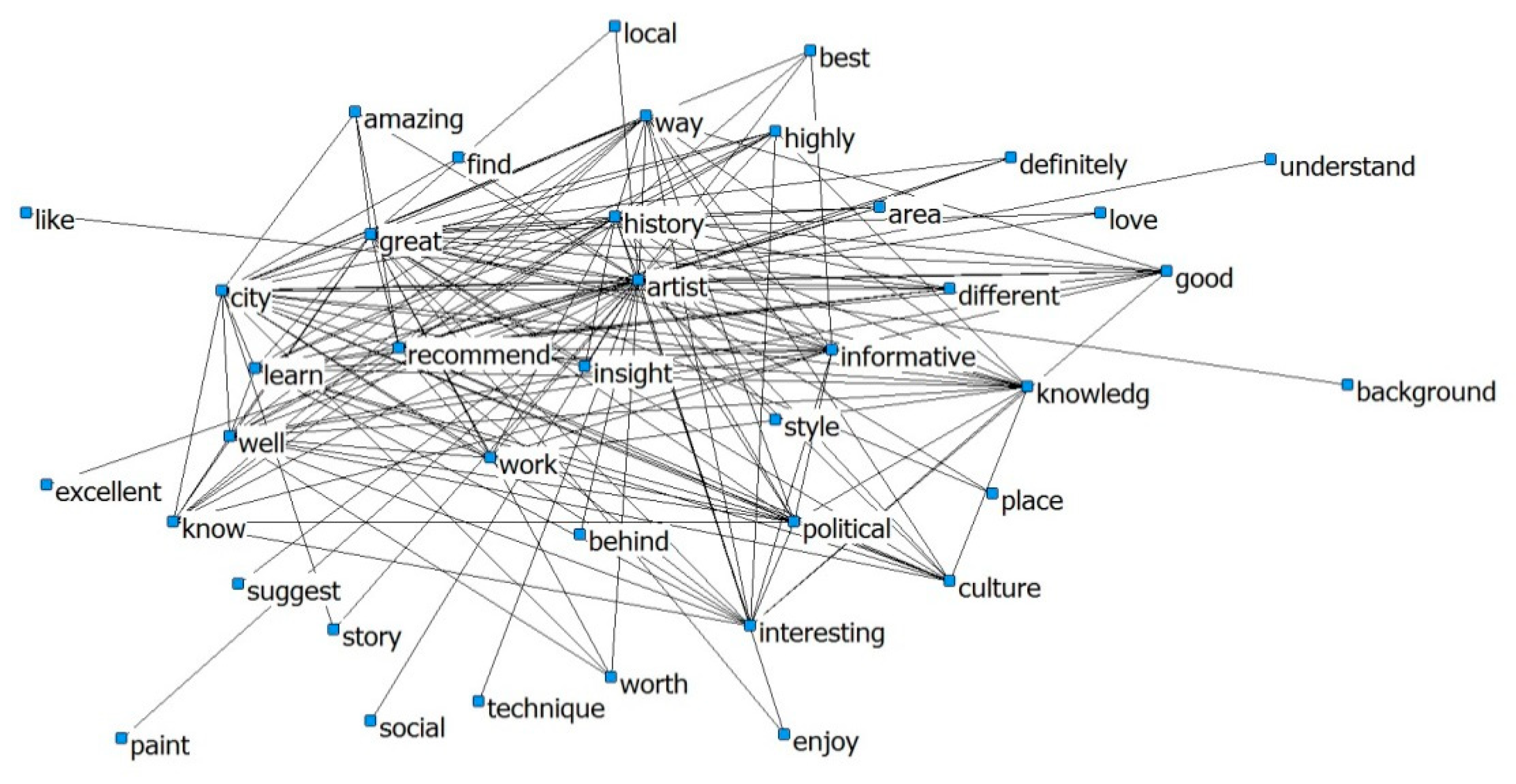

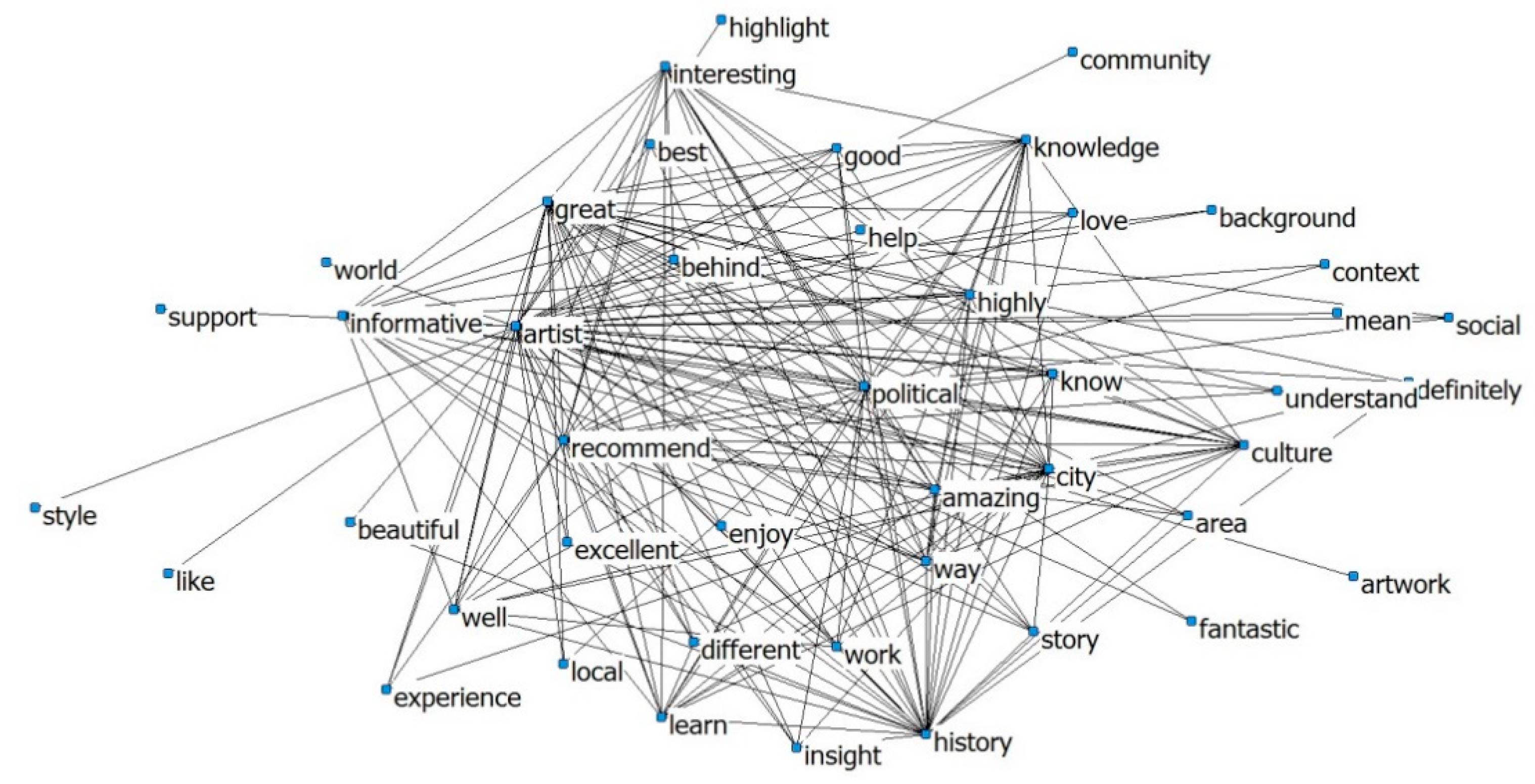

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Messaris, P. Visual communication: Theory and research. J. Commun. 2003, 53, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megler, V.; Banis, D.; Chang, H. Spatial analysis of graffiti in San Francisco. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 54, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.Y. Street Art: An Analysis under US Intellectual Property Law and Intellectual Property’s Negative Space Theory. DePaul J. Art Tech. Intell. Prop. L 2013, 24, 259. [Google Scholar]

- Haworth, B.; Bruce, E.; Iveson, K. Spatio-temporal analysis of graffiti occurrence in an inner-city urban environment. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 38, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators; Earthscan: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe, C. Graffiti or street art? Negotiating the moral geographies of the creative city. J. Urban Aff. 2012, 34, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Cities Culture Forum. Available online: http://www.worldcitiescultureforum.com/cities/bogota (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- UNWTO. Tourism Statistics Inbound Tourism: Compendium of Tourism Statistics Dataset; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, J. From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience in the new urban world. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A. Community resilience, policy corridors and the policy challenge. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, T. Graffiti as spatializing practice and performance. Rhizomes Cult. Stud. Emerg. Knowl. 2013, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, K.; Wollan, S.; Woodcock, I. Placing graffiti: Creating and contesting character in inner-city Melbourne. J. Urban Des. 2012, 17, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsey, M.; Young, A. ‘Our desires are ungovernable’ Writing graffiti in urban space. Theor. Criminol. 2006, 10, 275–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokras-Grabowska, J. Art-tourism space in Łódź: The example of the Urban Forms Gallery. Turyzm 2014, 24, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.A.; Mayzlin, D. The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, B.K. Insights from hashtag# supplychain and Twitter Analytics: Considering Twitter and Twitter data for supply chain practice and research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 165, 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Chiang, R.H.; Storey, V.C. Business intelligence and analytics: From big data to big impact. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 1165–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.A. Mining the Social Web: Data Mining Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Google+, GitHub, and More; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Lew, A.A. The geography of sustainable tourism development: An introduction. In Sustainable Tourism: Geographical Perspectives; Addison Wesley Longman Ltd.: Harlow, UK, 1998; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wight, P. Tools for Sustainable Analysis in Planning and Managing Tourism and Recreation in the Destination, Dalam Suatainable Tourism, a Geographical Perspective; Hall, C.M., Lew, A.A., Eds.; Longman: Harlow, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP, UNWTO. Making Tourism More Sustainable - A Guide for Policy Makers; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Donyadide, A. Ethics in tourism. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 17, 426–433. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Challenges of sustainable tourism development in the developing world: The case of Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, J.B. Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S. Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Annual Report 2017; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R. Sustainable tourism-looking backwards in order to progress? In Sustainable Tourism: A Geographical Perspective; Addison Wesley Longman Ltd.: Harlow, UK, 1998; pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Richins, H. Environmental, cultural, economic and socio-community sustainability: A framework for sustainable tourism in resort destinations. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2009, 11, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Turk, E.S. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. In Quality-of-Life Community Indicators for Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Huppatz, D. The Cave and the Retrospective Construction of Design. AMD Writing Intersections Conference Proceedings. 2009. Available online: https://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au/file/ad3a1aa9-a7bc-4f87-8591-3f08b0ddf6dc/1/PDF%20%28Published%20version%29.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2020).

- Drabsch, B.; Bourke, S. Early visual communication: Introducing the 6000-year-old Buon Frescoes from Teleilat Ghassul, Jordan. Arts 2019, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepworth, K. History, power and visual communication artefacts. Rethink. Hist. 2016, 20, 280–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, M. Audiences, aesthetics and affordances: Analysing practices of visual communication on social media. Digit. Cult. Soc. 2017, 3, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisel, D.L. Graffiti; Office of Community-oriented Policing Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, A.; Khanyile, S.; Joseph, K. Where Do We Draw the Line?: Graffiti in Maboneng, Johannesburg; Gauteng City Region Observatory (GCRO): Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.A. The writing on our walls: Finding solutions through distinguishing graffiti art from graffiti vandalism. U. Mich. JL Reform 1992, 26, 633. [Google Scholar]

- Weiler, B.; Hall, C.M. Special interest tourism: In search of an alternative. In Special Interest Tourism: In Search of an Alternative; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1992; pp. 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Zeppel, H. Review: Arts and Heritage Tourism. In Special Interest Tourism; Weiler, B., Hall, C.M., Eds.; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gratton, C.; Taylor, P. Impacts of festival events: A case study of Edinburgh. In Tourism and Spatial Transformations; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1995; pp. 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, H. Arts, Entertainment and Tourism; Taylor & Francis: Milton Park, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The Original Bogota Graffiti Tour. Available online: http://bogotagraffiti.com (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- UNWTO. World Tourism Barometer; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell, S.; Van der Duim, R.; Ankersmid, P.; Kelder, L. Measuring the sustainability of tourism in Manuel Antonio and Texel: A tourist perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2004, 12, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerario, A.; Di Turi, S. Sustainable urban tourism: Reflections on the need for building-related indicators. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Traditions in the qualitative sociology of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, V.; Abrahams, R.D.; Harris, A. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Inskeep, E. Tourism Planning: An Integrated and Sustainable Development Approach; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttle, F.A. Word of mouth: Understanding and managing referral marketing. J. Strateg. Mark. 1998, 6, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Yoo, K. Use and Impact of Online Travel Reviews Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism. In Proceedings of the International Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism Conference, Innsbruck, Austria, 23–25 January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.C.; Chambers, R.E. Marketing Leadership in Hospitality. Foundations and Practices; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Teichert, T.; Hu, F.; Li, H. How do tourists evaluate Chinese hotels at different cities? Mining online tourist reviewers for new insights. In Proceedings of the WHICEB, Wuhan, China, 27 May 2016; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Berezina, K.; Bilgihan, A.; Cobanoglu, C.; Okumus, F. Understanding satisfied and dissatisfied hotel customers: Text mining of online hotel reviews. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Jin, X. What do Airbnb users care about? An analysis of online review comments. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Lehto, X.Y.; Morrison, A.M. Destination image representation on the web: Content analysis of Macau travel related websites. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinger, A.; Lalicic, L.; Mazanec, J. Exploring the generalizability of discriminant word items and latent topics in online tourist reviews. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.-H.; Yang, S.-B.; Nam, K.; Koo, C. Conceptual foundations of a landmark personality scale based on a destination personality scale: Text mining of online reviews. Inf. Syst. Front. 2017, 19, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotts, J.C.; Mason, P.R.; Davis, B. Measuring guest satisfaction and competitive position in the hospitality and tourism industry: An application of stance-shift analysis to travel blog narratives. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chan, S.C.F.; Ngai, G.; Leong, H.-V. Quantifying reviewer credibility in online tourism. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Database and Expert Systems Applications, Prague, Czech Republic, 26–29 August 2013; pp. 381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Tripadvisor. Available online: http://tripadvisor.com (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Feldman, R.; Dagan, I. Knowledge Discovery in Textual Databases (KDT). In Proceedings of the KDD, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–21 August 1995; pp. 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, M.; Xu, J. Business intelligence in blogs: Understanding consumer interactions and communities. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 1189–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotho, A.; Nürnberger, A.; Paaß, G. A brief survey of text mining. In Proceedings of the Ldv Forum-GLDV J. Comput. Linguistics Lang. Technol., 13 May 2005; pp. 19–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, A.; Poteet, S.R. Natural Language Processing and Text Mining; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.; Hornik, K.; Feinerer, I. Text mining infrastructure in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, Y. Institutional network structure of corporate stakeholders regarding global corporate social responsibility issues. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1063–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.; Barnett, G.A. Globalization of technology: Network analysis of global patents and trademarks. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 1471–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, J.B. Writing urban space: Street art, democracy, and photographic cartography. Cult. Stud. Crit. Methodol. 2017, 17, 491–502. [Google Scholar]

| Sustainability Perspective | Contents |

|---|---|

| Economic sustainability | long-term economic operations, stable employment, income-earning opportunities, social services to host communities, poverty alleviation |

| Socio-cultural sustainability | socio-cultural authenticity, cultural heritage, traditional values, inter-cultural understanding and tolerance |

| Environmental sustainability | essential ecological processes, conserve natural heritage and biodiversity |

| Sustainability Perspective | Sub-Category |

|---|---|

| Economic sustainability |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Socio-cultural sustainability |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Environmental sustainability |

|

|

| Researcher | Definition of Art Tourism |

|---|---|

| Weiler and Hall [40] | Tourism activities in which one participates in performing arts and exhibiting arts |

| Zeppel [41] | Experiential art in which one participates and is motivated by art practices, visual arts, and art festivals |

| Gratton and Taylor [42] | Tourism activities consuming contemporary culture |

| Hughes [43] | Tourism activities that include participation in the fine arts, performing arts, cultural events, as well as festivals and entertainment |

| Rank | Word | Frequency | Rank | Word | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | artist | 1024 | 26 | worth | 214 |

| 2 | great | 959 | 27 | love | 209 |

| 3 | history | 849 | 28 | area | 208 |

| 4 | recommend | 815 | 29 | local | 206 |

| 5 | city | 780 | 30 | excellent | 197 |

| 6 | political | 608 | 31 | experience | 189 |

| 7 | knowledge | 588 | 32 | like | 187 |

| 8 | interesting | 550 | 33 | nice | 176 |

| 9 | informative | 541 | 34 | beautiful | 165 |

| 10 | learn | 494 | 35 | understand | 157 |

| 11 | way | 465 | 36 | social | 152 |

| 12 | well | 426 | 37 | background | 148 |

| 13 | culture | 424 | 38 | fantastic | 142 |

| 14 | amazing | 383 | 39 | incredible | 134 |

| 15 | highly | 379 | 40 | friendly | 133 |

| 16 | know | 352 | 41 | meaning | 133 |

| 17 | good | 326 | 42 | want | 129 |

| 18 | work | 320 | 43 | place | 122 |

| 19 | different | 270 | 44 | first | 121 |

| 20 | best | 248 | 45 | suggest | 120 |

| 21 | insight | 236 | 46 | style | 119 |

| 22 | behind | 231 | 47 | highlight | 113 |

| 23 | definitely | 231 | 48 | miss | 112 |

| 24 | story | 224 | 49 | awesome | 111 |

| 25 | enjoy | 221 | 50 | country | 111 |

| No. | Word | 2013~2016 | 2017~2019 | ② − ① | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Word Frequency | Frequency/The Number of Total Reviews ① | Rank | Word Frequency | Frequency/the Number of Total Reviews ② | |||

| 1 | artist | 1 | 440 | 0.58 | 1 | 584 | 0.48 | −0.10 |

| 2 | great | 2 | 412 | 0.54 | 2 | 547 | 0.45 | −0.09 |

| 3 | history | 5 | 307 | 0.40 | 3 | 542 | 0.44 | 0.04 |

| 4 | recommend | 4 | 316 | 0.41 | 4 | 500 | 0.41 | _ |

| 5 | city | 3 | 330 | 0.43 | 5 | 450 | 0.37 | −0.06 |

| 6 | political | 11 | 205 | 0.27 | 6 | 394 | 0.32 | 0.05 |

| 7 | knowledge | 6 | 257 | 0.34 | 7 | 331 | 0.27 | −0.07 |

| 8 | informative | 8 | 231 | 0.30 | 8 | 310 | 0.25 | −0.05 |

| 9 | learn | 10 | 220 | 0.29 | 9 | 306 | 0.25 | −0.04 |

| 10 | interesting | 7 | 245 | 0.32 | 10 | 304 | 0.25 | −0.07 |

| 11 | culture | 14 | 152 | 0.20 | 11 | 272 | 0.22 | 0.02 |

| 12 | amazing | 18 | 128 | 0.17 | 12 | 255 | 0.21 | 0.04 |

| 13 | way | 9 | 222 | 0.29 | 13 | 244 | 0.20 | −0.09 |

| 14 | highly | 16 | 144 | 0.19 | 14 | 233 | 0.19 | _ |

| 15 | well | 12 | 201 | 0.26 | 15 | 224 | 0.18 | −0.08 |

| 16 | good | 13 | 155 | 0.20 | 16 | 171 | 0.14 | −0.06 |

| 17 | work | 15 | 152 | 0.20 | 17 | 168 | 0.14 | −0.06 |

| 18 | behind | 29 | 75 | 0.10 | 18 | 157 | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| 19 | story | 32 | 75 | 0.10 | 19 | 149 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

| 20 | definitely | 26 | 93 | 0.12 | 20 | 138 | 0.11 | −0.01 |

| 21 | different | 19 | 133 | 0.17 | 21 | 137 | 0.11 | −0.06 |

| 22 | know | 17 | 126 | 0.16 | 22 | 137 | 0.11 | −0.05 |

| 23 | insight | 24 | 100 | 0.13 | 23 | 136 | 0.11 | −0.02 |

| 24 | best | 20 | 113 | 0.15 | 24 | 135 | 0.11 | −0.04 |

| 25 | excellent | 38 | 64 | 0.08 | 25 | 133 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| 26 | love | 27 | 87 | 0.11 | 26 | 121 | 0.10 | −0.01 |

| 27 | experience | 30 | 75 | 0.10 | 27 | 114 | 0.09 | −0.01 |

| 28 | enjoy | 21 | 108 | 0.14 | 28 | 113 | 0.09 | −0.05 |

| 29 | beautiful | 43 | 57 | 0.07 | 29 | 108 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| 30 | local | 25 | 99 | 0.13 | 30 | 107 | 0.09 | −0.04 |

| 31 | area | 23 | 102 | 0.13 | 31 | 106 | 0.09 | −0.04 |

| 32 | worth | 22 | 108 | 0.14 | 32 | 106 | 0.09 | −0.05 |

| 33 | nice | 34 | 71 | 0.09 | 33 | 105 | 0.09 | _ |

| 34 | fantastic | 67 | 39 | 0.05 | 34 | 103 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| 35 | like | 28 | 85 | 0.11 | 35 | 102 | 0.08 | −0.03 |

| 36 | social | 46 | 55 | 0.07 | 36 | 97 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| 37 | understand | 40 | 64 | 0.08 | 37 | 94 | 0.08 | _ |

| 38 | background | 45 | 55 | 0.07 | 38 | 93 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| 39 | meaning | 49 | 48 | 0.06 | 39 | 85 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| 40 | context | 85 | 29 | 0.04 | 40 | 79 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 41 | friendly | 41 | 59 | 0.08 | 41 | 74 | 0.06 | −0.02 |

| 42 | highlight | 60 | 41 | 0.05 | 42 | 72 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 43 | miss | 63 | 40 | 0.05 | 43 | 72 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 44 | artwork | 70 | 36 | 0.05 | 44 | 71 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 45 | absolutely | 65 | 40 | 0.05 | 45 | 70 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 46 | community | 79 | 32 | 0.04 | 46 | 68 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 47 | super | 78 | 32 | 0.04 | 47 | 68 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 48 | wonderful | 64 | 40 | 0.05 | 48 | 68 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 49 | awesome | 50 | 46 | 0.06 | 49 | 65 | 0.05 | −0.01 |

| 50 | perfect | 83 | 30 | 0.04 | 50 | 65 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| No. | Word | Reviews |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | political | “Great tour of Bogota’s graffiti, really insightful analysis of the political undertones and history that is incorporated into the art.” “The art work may seem just pretty but if you take a closer look, it’s very political with Strong messages.” |

| 2 | history | “The artists styles, their political views, plus history of the native Colombians and their struggle to keep their identity.” “Learned a lot about the history of people here and how changes in their socio-economic environment leads to freedom of expression through art.” |

| 3 | behind | “The art is impressive and the stories behind it are captivating.” “It was great to have a description of what the political and historical meanings were behind the art and artists.” |

| 4 | culture | “The graffiti tour was an excellent way to explore Bogota’s neighborhoods through the artistic and cultural lense of street art.” “Street art is a significant part of Colombian culture so you can see it everywhere - to understand the context is great.” |

| 5 | story | “As well as the art work being visually beautiful it was backed up with history, politics and stories of the artists.” “The Bogota Graffiti Tour is a brilliant way to explore the city and understand some of its political background and the stories behind Bogotas street art and it’s artists.” |

| 6 | context | “I’ve been living in Bogota for a while now and this greatly enriched my understanding of local street art as well as its social and political contexts in Colombia.” “Good knowledge shown of the street art and context social and political and the importance of this art in Bogota reflecting some of the indigenous people and political struggles as well as the legalities.” |

| 7 | community | “It was interesting and eye opening to hear the history and politics/political discord of Colombia through the artists’ eyes and how these artworks have worked with the community as well to strengthen them.” “I’ve learned a lot about graffiti artists and how graffiti can really make a difference for some troubled communities.” |

| 8 | artwork | “The tour was excellent, really informative, gave me a sense of the history and current issues of Bogota in such a short stay as well as seeing some amazing artwork.” “The tour captures not only the artists and how they create the work but also what the artwork represents which in turn informs you of Colombian society.” |

| 9 | background | “A complete different view on the city, but with many details on the history of the town, background stories on the art scene and as well as some political stuff.” “The tour not only gave an in-depth look at graffiti in the neighbourhood of the walk, but also a background of graffiti/street art in Colombia along with a recent history of the political state of the city of Bogota, and the country in general.” |

| 10 | social | “Pretty much the best thing to do in Bogota, not just for the art, but also to understand some of the social and political issues facing Bogota.” “Since the street art movement in Bogota began pretty much in 2011 most of the information is recent and relevant to the current social and political climate in Bogota.” |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seok, H.; Joo, Y.; Nam, Y. An Analysis of the Sustainable Tourism Value of Graffiti Tours through Social Media: Focusing on TripAdvisor Reviews of Graffiti Tours in Bogota, Colombia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114426

Seok H, Joo Y, Nam Y. An Analysis of the Sustainable Tourism Value of Graffiti Tours through Social Media: Focusing on TripAdvisor Reviews of Graffiti Tours in Bogota, Colombia. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114426

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeok, Hwayoon, Yeajin Joo, and Yoonjae Nam. 2020. "An Analysis of the Sustainable Tourism Value of Graffiti Tours through Social Media: Focusing on TripAdvisor Reviews of Graffiti Tours in Bogota, Colombia" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114426

APA StyleSeok, H., Joo, Y., & Nam, Y. (2020). An Analysis of the Sustainable Tourism Value of Graffiti Tours through Social Media: Focusing on TripAdvisor Reviews of Graffiti Tours in Bogota, Colombia. Sustainability, 12(11), 4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114426