1. Introduction

In 2015, the member countries of the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The core component of this agenda, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), point to the urgency of preserving the livelihood of the world’s population by challenging current environmental and social crises such as climate change, environmental pollution, overuse of natural resources, poverty and violent conflict [

1]. In this context, the global production and consumption of food becomes a considerably important aspect. In terms of climate change, food systems account for about 25% of the CO

2 emissions worldwide [

2]. Moreover, there are issues of food insecurity expressed in terms of limited access to sufficient and affordable nutrition, which still represents the reality for many people of the world.

Agenda 2030 explicitly states that city regions will have to play a crucial role in addressing these challenges at a local level [

1]. This call for local action resonates also with recent shifts in public perception being increasingly critical of traditional, globalized food systems and seeing promising leverage points for food sustainability rather at a local level [

3,

4]. Accordingly, new urban food policies have emerged over the past couple of years. For instance, cities like Vancouver, London or Detroit have already implemented their own strategies in order to address multiple food-related challenges in close cooperation with civil society actors. These programs not only intend to reduce environmental impacts but also aid urban self-sufficiency and support healthy eating habits among the population [

5,

6,

7].

A vibrant part of these local food strategies includes fostering local food initiatives and their activities. Overall, a multitude of different food initiatives have emerged recently [

8]: Commercial cooperatives such as farmers’ markets [

9], organic box schemes [

10] or food hubs [

11] strive to support local farmers by making regional and fresh food available to a larger part of city residents. Educational programs such as farm-to-school initiatives [

12] or cooking classes aim at improving communal health, nutritional knowledge and social cohesion. Finally, there are also initiatives that have more political ambitions, planning to bring about broader societal change and leading to transitions towards sustainability [

13,

14]. Examples for these transition-oriented initiatives are grassroots projects like community-based agriculture, urban gardening, food sharing or solidarity purchasing groups [

15]. As a form of political practices, these initiatives collectively challenge prevailing norms by evoking alternative concepts of open source, group solidarity, sharing, inclusive participation and political protest [

16,

17].

There is already a substantial amount of research available on food initiatives, with many of these studies devoted to the analysis of the potentially positive impacts of such initiatives on urban food systems. However, there are hardly any studies that deliver an analytical understanding of the organizational aspects of these collective food initiatives and the development of their activities. The current study attempts to provide this by addressing the following question: What are the key organizational characteristics that constitute different types of food initiatives? The answer to this question not only generates comprehensive insights into the initiatives’ organizational operations, it will also lead to a discussion about policy-relevant strategies on how to support these initiatives at a local level. Empirically, this study is based on a case study approach that compares two types of food initiatives organized around practices of urban gardening and joint cooking and eating.

The article has the following structure:

Section 2 provides an overview of the literature on urban gardening and communal cooking and eating initiatives.

Section 3 presents the chosen research approach and provides a short description of the case studies.

Section 4 shows the results along five distinct analytical dimensions. Finally,

Section 5 discusses the findings and affords recommendations on how local governments can effectively support food initiatives, which contribute to urban sustainability. The paper concludes with suggestions for future research.

3. Research Context

3.1. Methods

The research employs a comparative case study approach [

55] to illustrate key differences and patterns between food initiatives more systematically evident. In total, five food initiatives—two cases of urban gardening and three cases of joint cooking and eating—in two smaller cities in southern Germany were analyzed. Both cities have a population of about 20,000 people. They are rather wealthy and have sufficient financial resources available. While one of the cities economically benefits from its proximity to a larger city situated nearby, the other one mainly depends on thriving agriculture, dairy farming and tourism. Due to their economic status, social issues such as ethnic segregation, food insecurity, poverty or high unemployment rates play only a minor role for these cities.

In terms of collecting the data, the study builds on a mix of qualitative methods including interviews, participatory observations and document analysis.

Primarily, this study draws on 16 qualitative interviews, which were conducted between November 2018 and September 2019 in two smaller cities in Southern Germany. For each of these cases, three to four semi-structured interviews were carried out. Interviewees were either normal participants or people in charge of the respective initiative. On average, the interviews had a duration of between 30 and 45 min. For one of the cooking and eating cases, it was decided to conduct a group discussion instead of an interview due to pragmatic considerations. While gathering the data, the focus was on a two-fold interview strategy: On the one hand, the interviews were structured in accordance with a guideline, including questions targeting different aspects of the initiatives such as their development over time, the individual motives and responsibilities or the quality of the relationships between participants. On the other hand, open questions provided interviewees with the opportunity to speak for themselves and develop their own views [

56]. Interviews were transcribed verbatim.

In addition to these interviews, participatory observations were carried out at two urban gardening events and one cooking event. While in attendance, important results of the observations were recorded by writing short protocols that contained information about the initiatives’ procedures, participants’ behavior, informal conversations and group dynamics. Finally, this research considered various articles published by local newspapers that reported on these initiatives at the time of data collection.

Due to the explorative nature of this study, the analysis did not build on a monolithic framework. Rather, the interpretation was based on the state of research above, along with additional insights from social movement literature [

57,

58,

59], both of which served as sensitizing concepts. In a first step of analysis, these insights allowed to organize the empirical material and develop preliminary interpretations. In a second step, a more systematic analysis of all the data was conducted by means of the coding software MAXQDA

®. In an iterative process, the developed codes and categories were finally integrated into five overarching key dimensions.

The results section below will make use of some verbatim quotes to illustrate key points. Quotes from interviews will be referenced by means of indicating the first letter of the interviewee’s name and the corresponding line number from the transcript.

3.2. Food Initiatives Studied

The analysis is based on five case studies: two cases representing urban gardening (UG) initiatives and three cases representing cooking and eating (CE).

Table 1 provides descriptive information on the analyzed food initiatives. The original names of the initiatives have been changed and the cities have been coded (as “City A” and “City B”) to protect the identities of the interviewees.

The Edible City is a UG initiative founded by local citizens of City A in 2013. There are about 25–30 people involved in the initiative, although only half of them are truly active members. Altogether, the Edible City is responsible for two different spaces including a small-sized garden area (approximately 200 m2) and a bigger one (approximately 1000 m2) which is located in the city’s park. In these garden spaces, members grow mostly fruits, vegetables, herbs and flowers. The common gardening activities of the Edible City usually take place on Fridays. Afterwards, the members have their regular meetings where they distribute duties and responsibilities among the group, collectively vote on important decisions or organize public events, further generating attention for the initiative within the city. Inspired by the concept of “edible cities” and the related network, the initiative regards itself as part of a global urban gardening movement that promotes sustainable development by means of reconnecting people to their natural roots and emphasizing communal aspects. The initiative also pursues the concept of an “open space”, allowing free access and, at least partially, the opportunity for self-harvesting. Furthermore, several members offer educational courses, particularly focusing on gardening knowledge, sustainable growing methods and alternative modes of agriculture (especially permaculture).

The project of the Participatory Garden for Sustainable Living started in 2017 with a handful of ecologically motivated volunteers who aimed to raise locals’ awareness in City B for sustainable and healthy food production. This group of people began with the creation of a small garden complex just outside the city center. At that time, the garden comprised 10 to 15 garden plots, which the initiative offered for rent. Citizens who rented the gardens were free in their choice of what to grow but were expected to take care of said garden beds. In 2019, another larger gardening area was acquired next to these initial garden plots. Members of the garden then decided to cultivate this new area with the intention of strengthening the communal aspects of their initiative. However, the fact that the initiative was still in its early stages led to regular fluctuations in the number of active members. Today, the gardeners mostly grow crop plants such as potatoes or pumpkins. Similar to The Edible City, they organize regular meetings at the end of the week where members are invited to work together, to discuss organizational issues and to plan for future activities.

The CE initiative Intergenerational Lunch in City B gives elderly people and children of a local kindergarten the opportunity to eat together. Overall, the initiative prepares meals for around 40 seniors and 20 children, who are served once a week at the city hall. Since its inception 10 years ago, the project has been organized by a single person who receives financial support from a private foundation. Although this person is officially in charge of organizing and supervising the event, the initiative also depends on several volunteers who are primarily responsible for cooking and serving. The major idea behind this lunch offer is to attempt to tackle the issue of widespread social isolation among older residents and bring together two different generations by means of offering them a low-priced meal. While the kindergarten saves time by not having to cook for the children at noon, the elderly, particularly those of low income, benefit from the social dimension of keeping in touch with their peers.

Men in the Kitchen is a cooking class and part of the official program of an adult education center in City A. The event is scheduled every year in autumn. For five evenings in a row, a group of around ten men prepare a three-course meal together, under the supervision of a professional cook. During the event, the group learns different cooking techniques in accordance with recipes from a particular cuisine. The class usually ends with participants eating together what they have cooked. An important aspect of this course is that most participants are already acquainted with each other or are even on friendly terms. For this reason, these men participate in other leisure activities together as well, for instance in a local sports group. As this is a tight-knit group returning yearly for the course, the number of participants is very limited and new registrations are usually added to a waiting list.

The initiative of Youth Eats and Cooks includes two food activities regularly organized by a local youth club in City B. One social worker is in charge of organizing these two food events. First, the club has a weekly all-you-can-eat lunch that only costs 99 cents. With this offer, the youth club pursues the strategy of attracting the urban youth and bringing them together in an environment where they can socialize with their peers. Similar to the Intergenerational Lunch, the offer addresses young people from low-income households, many of whom also have an immigrant background. The lunch enjoys a high degree of popularity, having approximately 50 young visitors eating there each week. Second, the center also offers communal cooking events where young people are free to participate. Not only are the teenagers encouraged to get involved in this event with the aim of strengthening their self-confidence, but there is also a certain intercultural exchange included. For instance, some of the events were planned together with refugees and parts of the city’s immigrant population in order to give both sides the opportunity to interact and potentially overcome cultural barriers.

4. Results

The following section shows the findings of the comparison between the two UG initiatives and three CE initiatives. They are presented along the five key dimensions: institutional integration, recruiting mechanisms, goal setting, time management and types of knowledge.

4.1. Institutional Integration

All of the investigated CE initiatives were directly affiliated with public institutions in their respective cities: Men in the Kitchen is one of the courses offered by an adult education school. The events of Youth Eats and Cooks connect to the public social work of a local youth center. The Intergenerational Lunch is part of the cities’ social service for the elderly population.

This strong affiliation with or integration into public institutions provides major benefits for the CE initiatives, as they gain access to valuable infrastructure such as pre-installed kitchen spaces in public buildings. For instance, Youth Eats and Cooks organize their activities in the localities of their youth club, which provides a kitchen interior, cooking equipment and a spacious dining room.

The proximity to public institutions is also reflected in their modes of interaction. In the interviews, the people responsible for the activities reported about productive, longstanding personal relationships with representatives of the local authorities. On the other hand, the work of these initiatives received much recognition from the city’s administration. City officials emphasize the initiatives’ usefulness in terms of their activities to improve upon the living conditions of locals and contribute to an “urban common welfare”. City officials generally experience a feeling of “working on the same side”; for example, one interviewee appreciated the work of Youth Eats and Cooks for their capacity for getting young (often less privileged) people “off the streets” and providing them with a location where they feel more relaxed.

Finally, these initiatives are built upon stable and quite formalized structures. Events are mostly organized in advance by the people managing the activities. Interviewees explained and justified this regulated environment as a requirement for the CE events to “run as planned”. Participants take part in pre-supplied activities and are assigned a clear role, which is often a rather passive role with limited responsibilities.

By contrast, the analyzed UG initiatives are not tightly integrated into public institutions, but rather they build on the commitment of civil society actors. Therefore, they gain only limited support from the city administration. This is a challenge mainly in the start-up phase, especially because UG initiatives must look for an adequately sized space that provides fertile soil for growing plants. There is also no guarantee that they can manage these garden spaces over a longer period of time, if land use is based on fixed-term agreements granted by the city on a largely voluntary basis. Here, an interviewee pointed to the initiative’s “vulnerable status”, with their future hinging on the officials’ good will. In later phases, UG initiatives face new, but structurally similar challenges, e.g., being fully responsible for funding their activities, procuring the necessary landscaping tools or maintaining the existing infrastructure and garden aesthetics.

In addition to the challenging interactions with the city’s public institutions, the UG initiatives also have a difficult standing among the local population. Various gardeners described how people from the outside were skeptical of them, often questioning, in principle, the intentions behind their community efforts.

“Sometimes people came by and made fun of us and our installation of mulch beds. They asked what we were doing. I think this is because they could not see anything more than some straw-covered hills” (N: 34).

“I do not know how we are perceived, but I think many people from the outside do not take us and our work seriously” (G: 90).

Unlike the CE initiatives, the UG initiatives lack formal organizational structures. Instead, they put stronger emphasis on providing an environment where participants have a lot of freedom to work together and cooperate under self-imposed rules. This is also reflected in the informal character of the decision-making processes and shared responsibilities for keeping the initiative alive. Although some of the members criticized the openness of these structures for their time-consuming nature, the majority saw such a democratic approach as a positive aspect. Indeed, interviewees especially valued the “experimental” character of their initiatives, which resemble “open testing grounds”: Without imposing too many restrictions on their members, UG initiatives represent a space for individual creativity and experiencing innovative thoughts.

4.2. Recruiting Mechanisms

Attracting participants is an important concern for any urban food initiative. This was also generally confirmed in the interviews; however, there are again interesting differences between the individual food initiatives.

For CE initiatives, the main recruiting tool is their work program, which they customize to specific groups of people and their needs. For instance, the Intergenerational Lunch mainly addresses the elderly community by providing them with the opportunity to have lunch in a family-like environment. These programs can also change over time: In its initial phase, the Intergenerational Lunch was targeted towards a broader group of people of all ages, but after gaining more attention and facing capacity issues, the people in charge decided to limit their lunch offer to elderly people and children. This example also shows that if food initiatives primarily address a specific target group, they will—almost essentially—exclude other groups of people from their offers.

In their recruiting efforts, CE initiatives also benefit from their close institutional ties to public institutions and established structures. According to one interviewee from Youth Eats and Cooks, their program receives a lot of attention because teenagers usually hear about these events from their peers at school. Similarly, the Intergenerational Lunch benefits from its cooperation with the local church community and offers coupons as birthday presents, which are regularly handed out to locals within the community, thus serving as an invitation that promises a free meal in conjunction with positive social experiences.

The UG initiatives build on very different recruitment strategies. They do not work with a classical, marketing-like “target group” model but rather strive to attract any person who is generally interested in communal gardening activities. This is reflected in a broad set of widespread recruitment activities. Due to a lack of strong institutional basis and external support, they rely a lot on personal relationships and networking to draw the attention of potential participants. In the interviews, various people reported that they made initial contact with the UG initiative through family life, good friends or work relations. Another pivotal strategy is to increase the visible presence in the city in order to draw public attention and inform people about upcoming activities. The Edible City, for example, puts up signs, places flower tubs in front of shops and sells seeds during market hours as tangible objects that help them to promote (and sustain) their green spaces.

This largely undirected recruitment strategy presents two main challenges: First, a major concern for both initiatives studied is the challenge of establishing and binding a critical mass of people who are interested in participating, especially since a sufficient number of active participants is necessary to sustain the urban gardening project over time. Second, the initiatives struggle with a bias in their membership. Participants of the UG initiatives were fully aware that their projects are not truly diverse, but they still underlined the importance of addressing people with different socio-cultural backgrounds, lifestyles and ages:

“You will get the impression that we rather attract people of older ages but this is not what we actually want. We are also looking for young people or families with kids to get more involved in our project” (U: 54).

4.3. Goal Setting

A third distinctive feature of CE and UG cases is related to the question of how these urban food initiatives define their primary purposes and set their goals.

All three CE initiatives operate, as previously stated (

Section 4.1), on a clearly predefined work program that determines the initiatives’ priorities and their fields of activity. For example, the activities of the Intergenerational Lunch aim to provide the elderly with healthy food as well as opportunities to socialize with others. This means the initiative’s program is designed in direct response to the issues of unhealthy eating habits and loneliness in old age. Similarly, cooking classes serve an educational purpose by advancing food knowledge and cooking skills in private households. The initiatives design their programs “for” participants, but not “with them”. That gives participants limited to no opportunities for contributing their own ideas. Broadly speaking, taking part in in these activities leaves participants with the mere choice of whether to accept what is offered or stay away. Thus, it turns them into rather passive recipients of a given offer.

By contrast, the UG initiatives studied show a high degree of programmatic openness that has two consequences. First, it gives people the freedom to participate for a variety of individual reasons, which are essentially self-determined. While some interviewees reported that they use the garden mainly for recreational purposes, others use it in order to experience nature and self-efficacy, to learn more about gardening, or to become more politically involved in a community. A good example in this context is an Iranian woman from the Participatory Garden for Sustainable Living who explained that she does not necessarily take part in the initiative for social contact, but instead sees garden work as a leisure activity that reminds her of her own past experiences.

Second, if people join the UG initiatives for individual reasons, this implies that tensions might arise between members who have different opinions on what the goal and focus of the gardening project should be. This became especially evident during the interviews with different members of The Edible City, who are in stark disagreement on the general character and use of the garden plots: One group of participants preferred private gardening, whereas others insisted on keeping the community approach of The Edible City as their primary objective. If these tensions were to exceed a certain point, it may become necessary for the group to explicitly (re) negotiate the initiative’s goals. Reaching a consensus while equally respecting diverging opinions is not easy to accomplish and may even result in conflict, as one member confirmed by recalling these procedures as a difficult and time-consuming process.

4.4. Time Management

When actively participating in urban food initiatives, people have to “sacrifice” their time. Again, one sees marked differences between CE and UG initiatives.

For participants from CE initiatives, time was not a big issue; they do not experience much difficulty in synchronizing the initiatives’ time requirements with their daily schedules. First, the practices of CE usually do not last longer than a few hours. Second, events can be scheduled in a flexible way, especially because they are usually held indoors and take place regardless of the season, weather or daytime. This makes CE events easy to plan, as one interviewee from the cooking classes explained:

“We deliberately set the date of the events after the summer holidays […] on Thursday evenings. […] All of us are available on those dates.” (M: 47).

In contrast, UG initiatives show significantly different patterns with regard to time management and timing requirements. This is because getting involved in gardening is generally more time-consuming and entails a high workload for the participants. Gardening deals with organic material, meaning that plants grow at a slow pace, requiring almost an entire season before harvest. As a result, this needs long-term commitment and patience from the participants. However, even if participants invest a substantial amount of time in the cultivation of plants, there is no guarantee of success for their work; there are frequent crop failures, especially among inexperienced gardeners.

Practices of UG also come with the requirement of performing recurring tasks, such as weeding, watering or pest control. This entails an increased workload, a circumstance that can become particularly challenging if participants are financially disadvantaged and, thus, cannot afford to spend too much time on gardening activities. This, as a consequence, may also lead to social tensions within the group, e.g., when active members complain about others neglecting their garden allotments and letting them “run wild”.

Compared with the typical indoor location of CE events, members of UG initiatives work outdoors, meaning that these activities heavily depend on climate and weather conditions. These environmental factors, again, have consequences for group dynamics. Various interviewees have reported that the interest in outdoor gardening activities decreases on days with suboptimal weather conditions.

4.5. Types of Knowledge

Urban food initiatives and their practices produce, share and disseminate different types of knowledge and understandings. CE initiatives in particular, often have an explicit educational focus: In the kitchen, participants are supposed to improve their cooking skills, get to know new recipes or increase their awareness of high-quality food products. Furthermore, they build on the assumption that the experience of eating together creates learning effects, which not only train sensory skills but also help in the discovery or expansion of personal food preferences. Eating in a group can notably incite participants to test new things that are outside of their typical eating habits.

Even though people cook and eat differently, they share a common understanding of preparing and enjoying food based on traditional-experiential knowledge. What is important for CE initiatives is that people can easily relate to such practices, since they are part of mundane experiences in everyone’s lives. An interviewee from Youth Eats and Cooks described these food events as “low-threshold offers”, where teenagers have the opportunity to easily contribute and share their own experiences:

“You do not need any prior knowledge in order to participate in joint cooking. Each person contributes with sharing his or her personal experiences. Everyone has the opportunity to support the group, even if it is just by cutting vegetables” (B: 38).

People feel comfortable talking about food, which is why food often becomes a conversation starter in CE events. For instance, an older couple who regularly visit the Intergenerational Lunch reported that food conversations are very common among participants. While attending one of the events, it was observed how visitors talked about food by either complaining or by positively commenting on food visuals and taste. With almost anyone having an opinion on food based on personal experience, these talks can serve as an icebreaker and initiate first contact among people.

In contrast to the CE initiatives, which are mainly associated with traditional-experiential knowledge, the UG initiatives are oriented towards a more transformative type of knowledge. The members understand communal gardening as an opportunity to mobilize know-how for achieving fundamentally different, sustainable lifestyles.

While CE practices are mainly linked to the private lives of the participants, UG practices are often driven by motivations that are more political. Here, in both UG initiatives the concept of “urban commons” plays an important role. Members frequently reject the commercial use of gardens as a protest against the idea of private ownership in general. The idea of “communing” plays out on two different scales: First, at the level of the initiative itself, where members try to establish a sharing culture with everyone having equal access to the equipment and resources provided by the garden. Secondly, on a wider social scale, where UG initiatives come with the intention to offer alternative ideas and behavioral patterns through practice. The two UG initiatives that were studied explicitly aim at more long-term societal changes that go beyond the boundaries of the initiatives themselves. The members are convinced that their practices have a positive impact on the local environment and local citizens and, with that, they are driven to convince others of their ideas:

“Our project makes a difference. […] I can have an effect on the lifestyle and on our economy by getting other people to think differently about it” (W: 44).

At the same time, it is interesting to see how activists blend their understanding of UG as transformative and oriented towards the common good with more self-interested motivations. A good example is an interviewee who described how the idea of sharing allows her to escape from the responsibilities that she associates with a modern lifestyle:

“We have an ethical directive that says we are not working for profit. There is no need to become an owner […]. If I own that place, but then cannot work in the garden anymore, what happens with it? Thus, having no personal property provides me with more freedom” (Kr: 50).

4.6. Summary: Distinct Profiles of Two Urban Food Initiatives

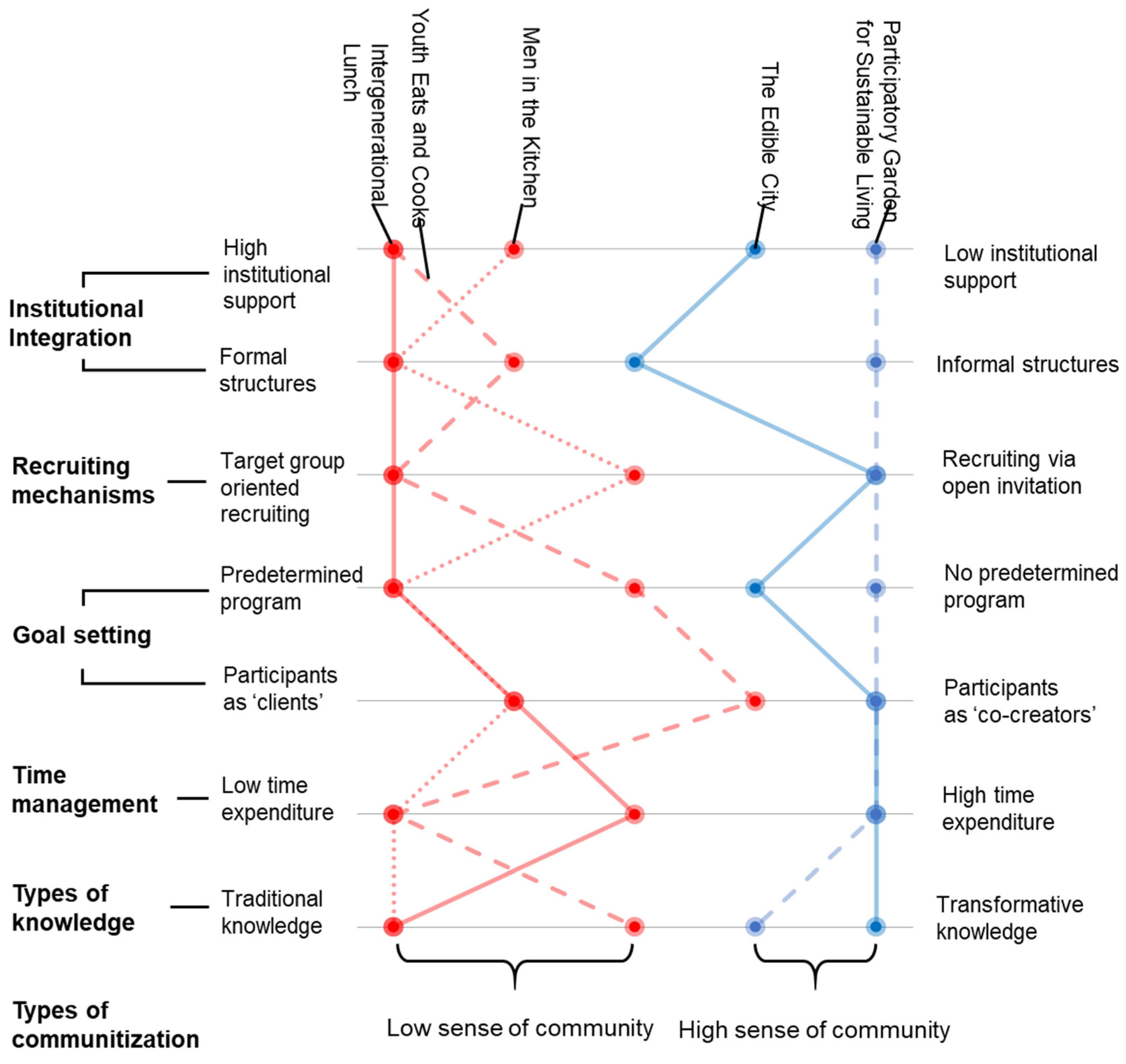

Figure 1 summarizes the empirical findings from the analysis of the five food initiatives in the form of a profile diagram. The profiles of CE initiatives are shown in red; these of UG initiatives are shown in blue.

As the profiles show, CE initiatives are marked by and benefit from their strong integration with public institutions; they build on established organizational structures; they operate with clearly defined work programs, which serve to address specific target groups. The activities often have an event-like character and, thus, require rather short-term commitments from potential participants. Lastly, CE initiatives—to a greater degree—draw on or mobilize more traditional, experiential types of knowledge.

On the other hand, UG initiatives mostly show a very low degree of public institutional integration; their structures are rather informal, which provides greater opportunities for the participants to become proactively involved. While these initiatives are generally open to everyone and allow collective debates on the initiatives’ main goals, they are also more time-consuming and demand long-term commitment from their members. Finally, UG initiatives are targeted at the creation of more transformative types of knowledge with which members critically challenge the status quo and encourage more eco-friendly practices not only with the initiatives themselves, but also on broader societal terms.

By way of summary, these profiles of urban food initiatives can be captured by two distinct types of communitization: CE initiatives are generally marked by a low sense of community. Although friendships may develop over time, participants are loosely affiliated with the group, since they identify as individuals, often just “clients”, who temporarily come together for a specific purpose. Activities within these food initiatives do not significantly affect the participants’ worldviews or “irritate” their personal lifestyles. Participants normally do not have a firm emotional commitment to the initiatives. This goes along with interviewees who preferred neither to be too involved in organizational tasks nor to be particularly responsible for the initiative’s future.

Contrary to the previous, UG initiatives are generally marked by a high sense of community. They provide an environment where members can identify with the practices, values and political ambitions that these initiatives stand for. Hence, members positively commented on feeling connected to each other, echoing a strong sense of community that grows over time. Furthermore, the UG initiatives themselves carry significant meaning for participants, as some of them emphasized how urban gardening has become part of their personal life. Due to the members’ affinity to the community identity, they are determined to keep the initiative alive and take on responsibilities on a voluntary basis.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

From an organizational perspective, the article highlights key aspects of urban gardening and joint cooking and eating as two kinds of organizational forms in the sphere of community food activism. Scholars largely agree that both studied types of food initiatives play an important role in advancing urban food systems towards sustainability [

36,

37,

47,

53]. This concluding section provides some policy-relevant insights based on a discussion of the study’s key findings, supplemented with and triangulated by relevant literature. The recommendations below are mainly directed at municipal decision makers, namely the people and organizations engaged in local food policies and strategies in a broader sense. The two distinctive organizational profiles of urban food initiatives presented above point to four entry points for their support: access to resources; integration into urban food politics; support in mobilization of membership; and leverage in overcoming general stereotypes among city decision makers and the broader public.

First, the analysis showed that local food initiatives all seem to be in need of additional resources for their development, though the nature of the resources required seems to differ according to type. The results revealed that UG initiatives heavily depend on gaining access to land, whereas CE initiatives have a particular need for adequate kitchen infrastructures. Starting with this, it can be inferred that UG initiatives seem to have a more fundamental resource problem; their requirements cannot be met by more pecuniary resources alone—unless they consider privatization of the garden plots, which was not an option in our case studies. Currently, UG initiatives often work rather independently and receive little attention from public institutions. Consequently, the initiatives require greater recognition from local governments, especially by seeing their resource needs recognized in urban planning processes and the mobilization of free city spaces that can be used to grow food [

59].

CE initiatives have a different organizational profile and, with that, different resource requirements. On the one hand, they have an advantage because of their comparatively close affiliation with public or social service institutions, which facilitates their acquisition of adequate kitchen spaces. On the other hand, there is also no guarantee for success, as Fridman and Lenters [

48] emphasized that finding a kitchen, particularly a centrally located one, can be challenging because it mostly depends on a cities’ capacities as to whether sufficient infrastructures and space are readily available. CE initiatives also have special requirements with regard to human resources and professional food safety expertise [

6].

A second insight from the analysis is that both types of urban food initiatives suffer from a lack of integration into urban food politics. When asking how municipal decision makers could promote the integration, one again sees differences according to the initiative’s type. UG initiatives are characterized by their role as “grassroots innovators” [

13], a role local governments could more actively draw upon. The results yield that UG initiatives are often based on a more “democratic” approach, mobilizing participants as co-creators who jointly agree on the initiatives’ goals and their concrete actions [

17,

18]. Moreover, UG initiatives draw on the participants’ ideas and competencies. Taking advantage of these collective knowledge resources can drive ecological and social innovations to improve resilience and sustainability. Thus, UG initiatives can help in advancing aspects of urban food sustainability that are not (yet) officially part of local policies. For public authorities, there are various ways of encouraging innovative UG activities, for instance, advertising best practices (e.g., sustainable farming methods) or fostering multi-sector collaborations across the urban food system. However, Rosol [

21] pointed out that expectations should not exceed the capacities of the initiatives by overstating the members’ voluntary commitment. The empirical results indicate a strong sense of community among UG participants, meaning that they are very much involved in the community “project” and identify with its communal values at a personal level. As a result, these initiatives bear the risk of individual self-exploitation (see also Werner [

27]).

CE initiatives are also frequently sidelined by local food politics, however, there are other reasons for their political marginalization. While UG initiatives tend to be “over-politicized” for connecting to politically mainstream processes, CE initiatives seem to be “under-politicized”. The findings of this study underline that CE initiatives themselves have little political ambitions with participants taking the role of passive clients who only receive social benefits on a voluntary basis. For example, the Intergenerational Lunch or Men in the Kitchen address problems of social isolation or unhealthy eating habits [

46,

47], but the structural conditions which created these food-related issues remain untouched [

50]. A notable exception is the initiative of Youth Eats and Cooks, which encourages young people to take a political stance towards certain food-related problems. Against that backdrop, local governments might consider strengthening the political voice of CE participants by organizing public events (e.g., awareness days or green festivals) or staging debates on sustainability issues with multiple local actors, including urban representatives and experts.

A third challenge that the examined urban food initiatives are facing is their lack of capacity to mobilize new members—again, with UG and CE initiatives struggling with different obstacles. The analyzed UG initiatives aim to get broad public attention in order to reach out to—and change the “foodways” of—as many fellow citizens as possible [

16]. These ambitions are often thwarted by the initiatives’ explicitly political aims. Ideas like “urban commoning” [

17,

60] or “viewing food as a public good, prioritizing its equitable distribution over profit” [

34] (p. 148) are well received by some parts of the population, but are seen as too radical by other parts who consequently feel discouraged to join UG activities. This mechanism of self-selection often leads to a high degree of homogeneity among participants [

61], even though many UG initiatives like the Edible City or the Participatory Garden for Sustainable Living would like to have more diversity based on their approach of actively addressing interested locals via open invitation. City officials might help UG initiatives to bridge the gap, for instance, by putting more emphasis on the specific needs of the people living in the neighborhood. This might be, as in the case of our UG initiatives studied, health or leisure benefits of working outdoors [

39], but it might in other socio-economic city contexts also be benefits related to social inclusion.

As illustrated by the case studies above, CE initiatives have less difficulty in attracting people and bringing them together. This is mainly because these initiatives build on target group-oriented recruiting strategies and they expect less from their participants, who must neither take on responsibilities nor invest much time into (pre-planned) activities. Despite this rather passive role of its individual members, CE initiatives as a whole still unfold a number of social benefits as they support people to facilitate better connections with each other. This is why Fridman and Lenters [

48] identified food activities as a “catalyst” for urban community building. However, the target group-oriented recruiting strategies of CE initiatives oftentimes result in rather confined community building effects. Thus, city officials might incentivize CE initiatives to offer a greater variety of activities in order to cover skills and taste preferences of people from different social backgrounds [

50]. Integrative food activities that target various audiences and their interests can better function as a “connective tissue between citizens, civil society and public service” [

49] (p. 199).

A fourth challenge that local food initiatives in this study are facing is tied to stereotypical attributions by the public and local decision makers. As indicated by the study’s findings, UG initiatives with their progressive goals and approaches are often perceived as “freaky outsiders” by city officials and the broader public. Locals usually remain skeptical towards UG projects in their neighborhoods, which goes hand in hand with initiatives not receiving sufficient appreciation from city officials [

62]. One solution would be providing platforms for mutual exchange. Making shared but also conflicting interests between urban gardeners and other actors in the urban food system more transparent could help reduce negative stereotypes, such as the fact that some of the local population sees urban gardening only as an attempt to privatize public spaces. However, transparency and communication cannot resolve all conflicts. This holds particularly true if city officials only intend to use urban gardening as a “marketing strategy around food and sustainability” [

63] (p. 9).

In contrast to UG initiatives, CE initiatives face a less hostile urban environment. With their adapted, service-oriented profile, they have a better overall reputation among the broader public and city officials tend to give them higher recognition for the services they provide for community use. However, this positive perception comes with the risk of overestimating the initiatives’ abilities and their integrative effects. Local governments might be tempted to see CE initiatives as an “easy way out” of dealing with recurring social issues for which the offers of CE initiatives do not go far enough.

Based on the analysis of food initiatives from smaller cities in southern Germany, it can be concluded that organizational aspects matter, both regarding a more systematic understanding of urban food initiatives and their differences as well as possible entry points for local decision makers on how to support these food initiatives in their development.

With its case study-based approach and the analysis of only two out of a greater variety of types of initiatives, this paper clearly leaves many questions unanswered. Future research could engage in both broadening the conceptual scope and expanding the empirical basis. Conceptually, there is not only the possibility to explore additional organizational key dimensions but also to devote more attention to how these dimensions relate to each other. Empirically, research could strive to examine a greater number and variety of case studies as well as their contexts. For example, it would be worthwhile to learn about the specificities of other types of food initiatives such as food sharing, solidarity food services or community driven urban farming. Likewise, it would be interesting to see whether and how the particular city context matters. All the cases analyzed in this study were located in smaller cities. However, food initiatives emerge in cities with very different sizes, structures and types of population. Since it is to be expected that the urban environment critically affects the way in which food initiatives organize their activities and how community development progresses, it needs broader and more systematically comparative research. This type of research could not only meet the knowledge needs of the scientific community but also provide better practical guidance for urban policies and municipal decision makers who accept the challenge of creating sustainable food systems in close cooperation with local food initiatives.