Resource Orchestration in Corporate Social Responsibility Actions: The Case of “Roteiros de Charme” Hotel Association

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Resource Orchestration

2.2. Network

2.3. Corporate Social Responsibility

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Semi-Structured Script

References

- Acquier, A.; Gond, J.P.; Pasquero, J. Rediscovering Howard R. Bowen’s legacy: The unachieved agenda of social responsibilities of the businessman and its continuous relevance. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 607–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.D.; McLaughlin, C.P. The impact of environmental management on firm performance. Manag. Sci. 1996, 42, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Gilbert, B.A. Resource orchestration to create competitive advantage breadth, depth, and life cycle effects. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1390–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Foster, P.C. The network paradigm in organizational research: A review and typology. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 991–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.; Peteraf, M. The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.A.; Boal, K.B. Strategic resources: Traits, configurations and paths to sustainable competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priem, R.L.; Butler, J.E. Is the resource-based ‘view’ a useful perspective for strategic management research? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D. Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside the black box. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Stigliani, I. Entrepreneurship and growth. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufteros, X.; Verghese, A.J.; Lucianetti, L. The effect of performance measurement systems on firm performance: A cross-sectional and a longitudinal study. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, C.; Super, J.F.; Kwon, K. Resource orchestration in practice: CEO emphasis on SHRM, commitment-based HR systems, and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Pan, S.L. Developing focal capabilities for e-commerce adoption: A resource orchestration perspective. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, A.; Simone, G.; Bruno, R. Resource orchestration in the context of knowledge resources acquisition and divestment. The empirical evidence from the Italian “Serie A” football. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wowak, K.D.; Craighead, C.W.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M. Toward a ‘Theoretical Toolbox’ for the supplier-enabled fuzzy front end of the new product development process. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 52, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F.; Sirmon, D.G.; Sciascia, S.; Mazzola, P. Resource orchestration in family firms: Investigating how entrepreneurial orientation, generational involvement, and participative strategy affect performance. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2011, 5, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.; Finkelstein, S.; Mitchell, W.; Peteraf, M.; Singh, H.; Teece, D.; Winter, S. Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organizations; Blackwell Publishers: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Sirmon, D.G.; Trahms, C.A. Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating value for individuals, organizations, and society. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 25, 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ketchen, D.J.; Wowak, K.D.; Craighead, C.W. Resource gaps and resource orchestration shortfalls in supply chain management: The case of product recalls. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, W.J.; Patel, P.C.; Parida, V.; Kreiser, P.M. Nonlinear effects of entrepreneurial orientation on small firm performance: The moderating role of resource orchestration capabilities. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2013, 7, 93–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. A Era da Informação: Economia, Sociedade e Cultura; Paz e Terra: São Paulo, Brazil, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Grandori, A.; Soda, G. Inter-firm networks: Antecedents, mechanisms and forms. Organ. Stud. 1995, 16, 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martes, A.C.B.; Bulgacov, S.; Nascimento, M.R.D.; Gonçalves, S.A.; Augusto, P.M. Fórum-redes sociais e interorganizacionais. Rev. Adm. Empresas 2006, 46, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, M.; Moinet, N. La Stratégie-Réseau; Éditions Zéro Heure: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Balestrin, A.; Vargas, L.M. A Dimensão Estratégica das Redes Horizontais de PMEs: Teorizações e Evidências. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S1415–65552004000500011&script=sci_abstract&tlng=pt (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Carvalho, M.M.; Lautindo, F.J.B. Estratégia competitiva: Dos conceitos à implementação. 2. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2010. Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivo, H.C.; Mares, A.I. Retrospectiva de la responsabilidad social empresarial a través del desarrollo del pensamiento econômico. Revista Universo Contábil. FURB 2009, 5, 116–133. [Google Scholar]

- Del Baldo, M. Corporate social responsibility and corporate governance in Italian SMEs: The experience of some ‘spirited businesses. J. Manag. Gov. 2012, 16, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppa, M.; Sriramesh, K. Corporate Social Responsibility among SMEs in Italy. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8814/f62366ae787092b6a3849e8cac7e6d20572e.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Andriof, J.; McIntosh, M. Perspectives on Corporate Citizenship; Greenleaf Publishing: Abingdon, England, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, L.B.; Boehe, D.M.; Ogasavara, M.H. CSR-based differentiation strategy of export firms from developing countries: An exploratory study of the strategy tripod. Bus. Soc. 2015, 54, 723–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, T.; Stark, W. Strategy development: Conceptual framework on corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Zientara, P.; Novotna, E. International hotel chains and environmental protection: An analysis of Hilton’s we care! programme (Europe, 2006–2008). J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaeian, V.; Khong, K.W.; Yeoh, K.K.; McCabe, S. Motivations of undertaking CSR initiatives by independent hotels: A holistic approach. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2468–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D.D.P.; Ortiz, J.A.; Cardona, J.R. Determinants of CSR Application in the Hotel Industry of the Colombian Caribbean. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.M.M.; Mogollón, J.M.H.; Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Fernández, J.A.F. Corporate Social Responsibility in Hotels: A Proposal of a Measurement of its Performance through Marketing Variables. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Zientara, P. Corporate social responsibility in hospitality: Issues and implications. A case study of Scandic. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 8, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Garay, L.; Jones, S. Sustainability motivations and practices in small tourism enterprises in European protected areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W. Linkages between tourism and agriculture for inclusive development in Tanzania: A value chain perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2018, 1, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Park, J.; Chi, C.G.Q. Consequences of ‘greenwashing.’ Consumers’ reactions to hotels’ green initiatives. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1054–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C.; Shulman, D.; Weinberg, A.; Gran, B. Complexity, generality, and qualitative comparative analysis. Field Methods 2003, 15, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roteiros de Charme. Available online: http://http://www.roteirosdecharme.com (accessed on 2 January 2017).

- Estalagem St. Hubertus. Available online: http://www.sthubertus.com (accessed on 2 January 2017).

- Pousada Cravo e Canela. Available online: http://www.pousadacravoecanela.com (accessed on 2 January 2017).

- Parador Casa Da Montanha. Available online: http://www.paradorcasadamontanha.com (accessed on 2 January 2017).

- Estalagem La Hacienda. Available online: http://www.lahacienda.com (accessed on 2 January 2017).

- Pousada Do Engenho. Available online: http://www.pousadadoengenho.com (accessed on 2 January 2017).

- Ragin, C.C. The Comparative Method: Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rihoux, B. Qualitative and quantitative worlds? A retrospective and prospective view on qualitative comparative analysis. Field Methods 2003, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Determinants of interorganizational relationships: Integration and future directions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benington, J. Partnerships as networked governance? Legitimation, innovation, problem-solving and co-ordination. In Local Partnerships and Social Exclusion in the European Union–New Forms of Local Social Governance; Geddes, M., Benington, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, England, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschoore, J.R.; Balestrin, A. Fatores relevantes para o estabelecimento de redes de cooperação entre empresas do Rio Grande do Sul. Rev. Adm. Contemp. 2008, 12, 1043–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A.; Vaidyanath, D. Alliance management as a source of competitive advantage. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, C.D.; Richard, O.C.; Peng, M.W.; Hasenhuttl, M. Alliance network centrality, board composition, and corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 151, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Zardini, A. Is sustainability competitive advantage for small businesses? An empirical analysis of possible mediators in the sustainability-financial performance relationship. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasker, R.D.; Weiss, E.S.; Miller, R. Partnership synergy: A practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Q. 2001, 79, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milwood, P.A.; Roehl, W.S. Orchestration of innovation networks in collaborative settings. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2562–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company | Location | Date of Association | Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estalagem St Hubertus [45] | Gramado/RS | 1998 | -Category: Topázio Imperial (classification given by the hotel association in which a hotel is well equipped, with adequate facilities and social spaces, high-level services, style and exquisite decoration); -Environmental conduct in which it aims at the use of alternative energy such as solar energy for heating the water; substation and own generator; the presence of sensors in the corridors; use of low-energy lamps; PVC and double glass frames, capable of maintaining energy in the environment; implementation of environmental practices such as the use of a sauna at a guest’s request; power switches; bath towel changing system, allowing guests to participate in the program; moderate use of water; use of recyclable paper; awareness of the whole team for actions and simple, day-to-day care. |

| Pousada Cravo e Canela [46] | Canela/RS | 2005 | -Category: Água Marinha (classification given by the hotel association in which a hotel whose decoration, good service value the local environment and characteristics); -Built-in a historic mansion that belonged to a former governor of the state of RS. |

| Parador Casa da Montanha [47] | Cambará do Sul/RS | 2006 | -Category: Pedra Ametista (classification given by the hotel association in which a hotel is located in an ecological paradise, where the unpretentious service and the decoration maintain identity with the region); -The hotel is located on a farm near the Aparados da Serra National Park and the Itaimbezinho Canyon, in the Campos de Cima da Serra, and has the ecovillage concept, in which guests stay in thermal huts inspired by African lodges. |

| Estalagem La Hacienda [48] | Gramado/RS | 2009 | -Category: Topázio Imperial (classification given by the hotel association in which a hotel is well equipped, with adequate facilities and social spaces, high-level services, style and exquisite decoration); -It has only six chalets and is situated in an area of 70 hectares with preserved forest, waterfalls, streams and lakes. |

| Pousada do Engenho [49] | São Francisco de Paula/RS | 2011 | -Category: Pedra Esmeralda (classification given by the hotel association in which a hotel has a privileged location, generous spaces, facilities and services that meet the standards of the traditional international hotel industry); -The huts were built to favour integration with the green surroundings. -Actions are developed aimed at taking care of the of constructions until the treatment of effluents, such as the used water that comes almost entirely from a slope that is on the property. Effluents are treated locally; there is the use of organic products, which are planted on the property; separation of garbage and compost from organic waste; use of a saline system instead of chlorine for the pool water and hot tub; and care for the property without the use of chemicals. |

| Interviewee | Company | Position |

|---|---|---|

| E1 | Pousada Cravo & Canela–Canela/RS | Owner |

| E2 | Parador Casa da Montanha–Cambará do Sul/RS | Quality manager |

| E3 | Estalagem La Hacienda–Gramado/RS | Manager |

| E4 | Pousada do Engenho–São Francisco de Paula/RS | Administrator |

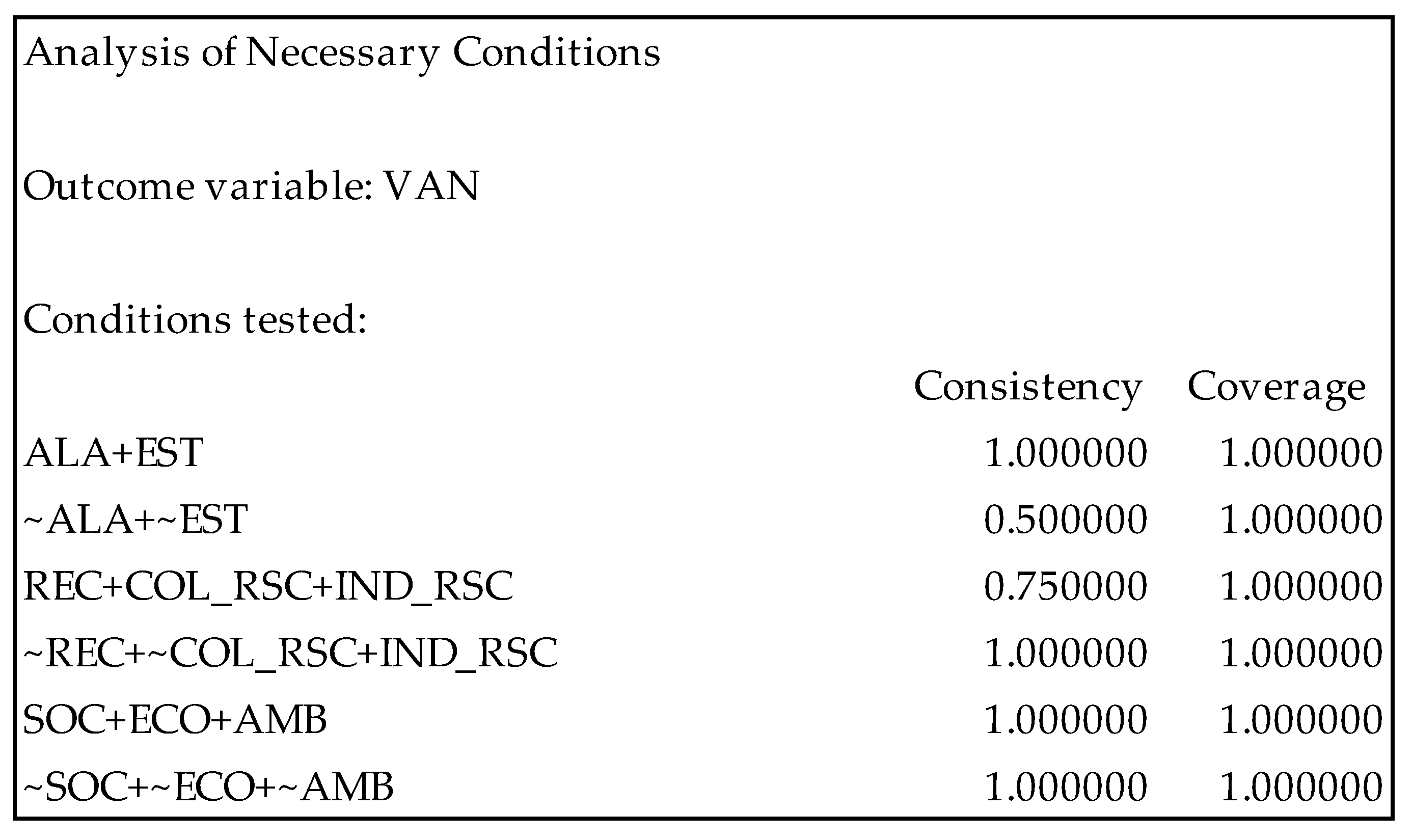

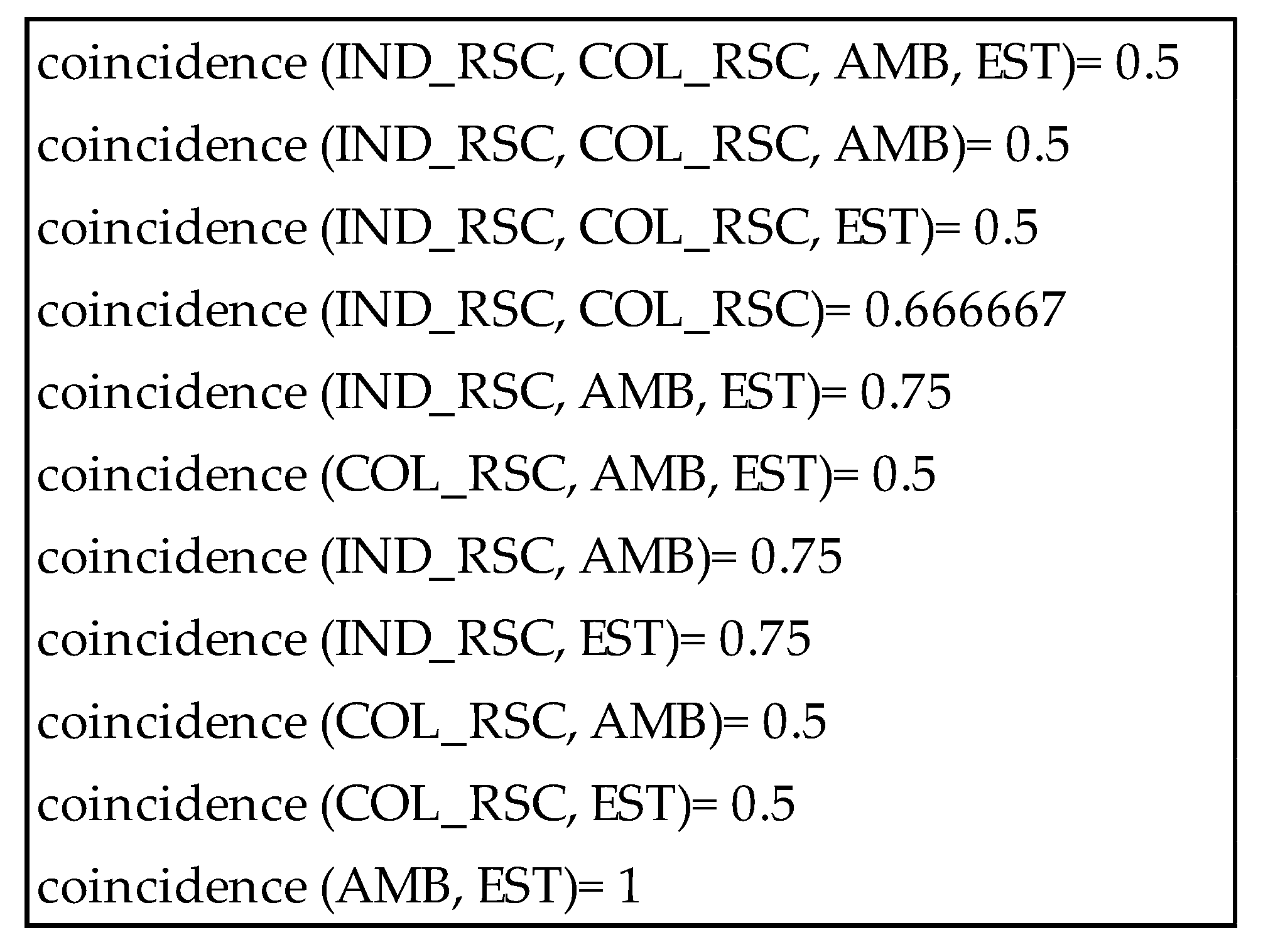

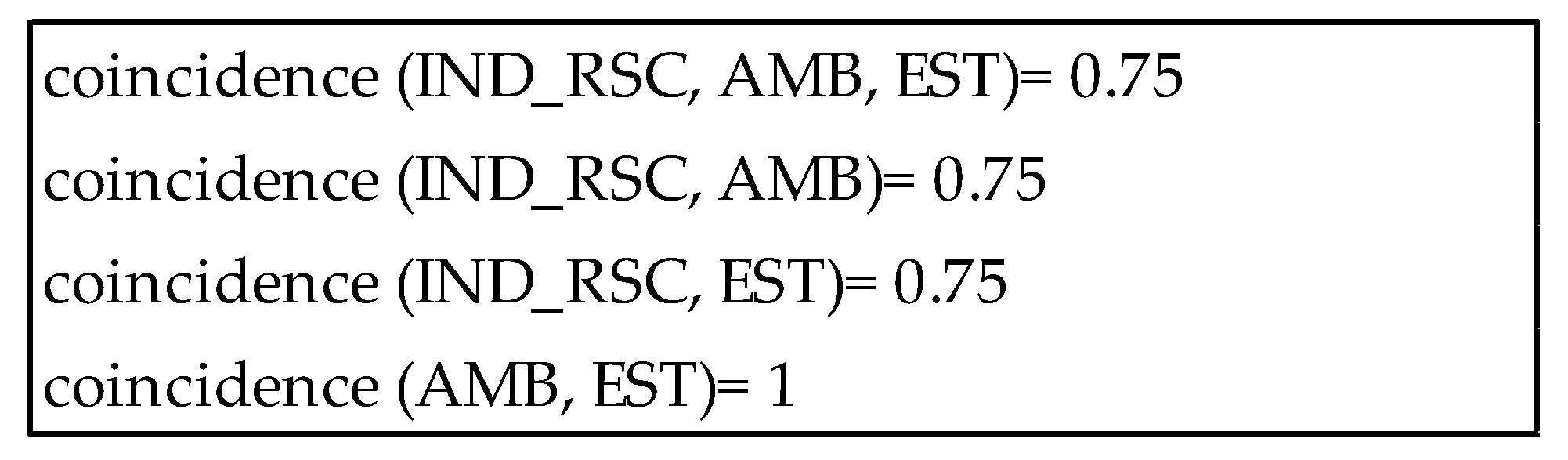

| Condition (Code) | Rational Analysis | Dichotomy |

|---|---|---|

| Creation of resource-based competitive advantage (VAN) | When there is a specific combination of features and capabilities. | (1) Presence of specific resources and capabilities; (0) Absence of specific resources and capabilities. |

| Leveraging enterprise-only resources (ALA) | When the mechanisms of mobilization and coordination are synchronized. | (1) Presence of mobilization and coordination mechanisms; (0) Absence of mobilization and coordination mechanisms. |

| Structuring the enterprise resource portfolio (EST) | When resources to build capabilities are aggregated and leveraged. | (1) Presence of exclusive resources; (0) No exclusive resources. |

| Reciprocity in the interorganizational relationship (REC) | When there is the mutuality of benefits acquired by the hotel association, based on cooperation. | (1) Presence of reciprocity; (0) Absence of reciprocity. |

| Collective strategies for corporate social responsibility (COL_RSC) | The influence of the hotel association on the collective strategies of small companies within the framework of CSR. | (1) Presence of hotel association influence within CSR; (0) Absence of hotel association influence within the framework of CSR. |

| Individual Strategies for Corporate Social Responsibility (IND_RSC) | The influence of individual small business strategies in the hotel association within the framework of CSR. | (1) Presence of small business influence within CSR; (0) Lack of influence of small companies in the context of CSR. |

| Social impact of CSR actions (SOC) | When there is involvement in external social issues, such as education, social inclusion, generation and volunteering of employees. | (1) Presence of social actions; (0) Absence of social actions. |

| The economic impact of CSR actions (ECO) | When there is involvement in issues related to jobs, ethical training standards and product value. | (1) Presence of economic actions; (0) Absence of economic actions. |

| Impact on the environment of CSR actions (AMB) | When there is involvement in issues such as emissions and waste control, energy use, product lifecycle and sustainable development. | (1) Presence of environmental actions; (0) Absence of environmental actions. |

| Solution | Causal Conditions * | Raw Coverage | Unique Coverage | Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex | ALA*EST*~REC*~COL_RSC*~SOC*~ ECO*AMB | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| ~ALA*EST*~REC*COL_RSC*IND_RSC*~ ECON*AMB | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Intermediate | ALA*EST*~REC*~COL_RSC*~SOC*~ ECO*AMB | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| ~ALA*EST*~REC*COL_RSC*IND_RSC*~ ECON*AMB | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maines da Silva, L.; Maines da Silva, P. Resource Orchestration in Corporate Social Responsibility Actions: The Case of “Roteiros de Charme” Hotel Association. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114448

Maines da Silva L, Maines da Silva P. Resource Orchestration in Corporate Social Responsibility Actions: The Case of “Roteiros de Charme” Hotel Association. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114448

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaines da Silva, Luciana, and Paula Maines da Silva. 2020. "Resource Orchestration in Corporate Social Responsibility Actions: The Case of “Roteiros de Charme” Hotel Association" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114448

APA StyleMaines da Silva, L., & Maines da Silva, P. (2020). Resource Orchestration in Corporate Social Responsibility Actions: The Case of “Roteiros de Charme” Hotel Association. Sustainability, 12(11), 4448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114448