Understanding Future Leaders: How Are Personal Values of Generations Y and Z Tailored to Leadership in Industry 4.0?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

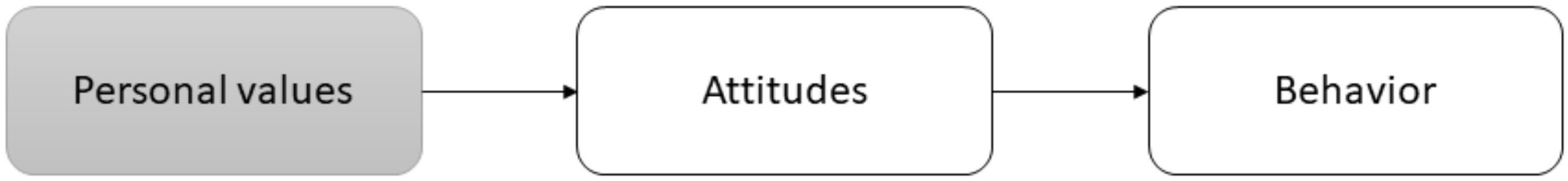

2.1. Personal Values

2.2. The Role of Personal Values in Leadership

2.3. Leadership in Industry 4.0

2.4. Generations Y and Z and Their Personal Values in the Industry 4.0 Workplace

3. Methodology

3.1. Instrument

3.2. Sample and Procedure

3.3. Measures

3.4. Research Design

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Regression Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Implications for Practice

5.3. Limitations

5.4. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Metallo, C.; Agrifoglio, B.; Schiavone, F.; Mueller, J. Understanding business model in the Internet of Things industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 136, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.M.; Kiel, D.; Voigt, K.-I. What Drives the Implementation of Industry 4.0? The Role of Opportunities and Challenges in the Context of Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.S.; Parry, E. Multigenerational Research in Human Resource Management. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Buckley, M.R., Halbesleben, J.R.B., Wheeler, A.R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2016; Volume 34, pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Piccarozzi, M.; Aquilani, B.; Gatti, C. Industry 4.0 in Management Studies: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.; Lee, C.; Taylor, M.S.; Zhao, H.H. Does Proactive Personality Matter in Leadership Transitions? Effects of Proactive Personality on New Leader Identification and Responses to New Leaders and their Change Agendas. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 64, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brixner, C.; Isaak, P.; Mochi, S.; Ozono, M.; Suarez, D.; Yoguel, G. Back to the future. Is industry 4.0 a new tecno-organizational paradigm? Implications for Latin American countries. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettel, M.; Friederichsen, N.; Keller, M.; Rosen, M. How Virtualization, Decentralization and Network Building Change the Manufacturing Landscape: An Industry 4.0 Perspective. Int. J. Mech. Ind. Sci. Eng. 2014, 8, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla, S.H.; Silva, H.R.O.; da Silva, M.T.; Gonçalves, R.F.; Sacomano, J.B. Industry 4.0 and Sustainability Implications: A Scenario-Based Analysis of the Impacts and Challenges. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, W.; Hämmerle, M.; Schlund, S.; Vocke, C. Transforming to a Hyper-Connected Hypper-Connected Society and Economy—Towards an “Industry 4.0. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Muiña, F.E.; Medina-Salgado, M.S.; Ferrari, A.M.; Cucchi, M. Sustainability Transition in Industry 4.0 and Smart Manufacturing with the Triple-Layered Business Model Canvas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2364. [Google Scholar]

- Erol, S.; Jäger, A.; Hold, P.; Ott, K.; Sihn, W. Tangible Industry 4.0: A Scenario-Based Approach to Learning for the Future of Production. Procedia CIRP 2016, 54, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prifti, L.; Knigge, M.; Kienegger, H.; Krcmar, H. A Competency Model for “Industrie 4.0” Employees. In Proceedings of the 13. Internationalen Tagung Wirtschaftsinformatik, St. Gallen, Switzerland, 12–15 February 2017; pp. 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schuh, G.; Anderl, R.; Gausemeier, J.; ten Hompel, M.; Wahlster, W. Industrie 4.0—Maturity Index. Managing the Digital Transformation of Companies (acatech STUDY); Schuh, G.A.R., Gausemeier, J., ten Hompel, M., Wahlster, W., Eds.; Herbert Utz Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grzybowska, K.; Anna, Ł. Key competencies for Industry 4.0. Econ. Manag. Innov. 2017, 1, 250–253. [Google Scholar]

- Waples, C.J.; Brachle, B.J. Recruiting millennials: Exploring the impact of CSR involvement and pay signaling on organizational attractiveness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.A. Leadership in Organizations; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, E.S.W.; Schweitzer, L.; Lyons, S.T. New Generation, Great Expectations: A Field Study of the Millennial Generation. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M. A Review of the Empirical Evidence on Generational Differences in Work Attitudes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. Discovering the Millennials’ Personal Values Orientation: A Comparison to Two Managerial Populations. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenarts, P.J. Now Arriving: Surgical Trainees from Generation Z. J. Surg. Educ. 2020, 77, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, L.F.C.; Lay, E.G.E. Personal values and leadership effectiveness. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, D.A.; Egri, C.P.; Reynaud, E.; Srinivasan, N.; Furrer, O.; Brock, D.; Alas, R.; Wangenheim, F.; Darder, F.L.; Kuo, C.; et al. A Twenty-First Century Assessment of Values across the Global Workforce. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.B. Researching managerial values: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egri, C.P.; Ralston, D.A. Generation Cohorts and Personal Values: A Comparison of China and the United States. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egri, C.P.; Herman, S. Leadership in the North American Environmental Sector: Values, Leadership Styles, and Contexts of Environmental Leaders and Their Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 571–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, B.Z. Values and the American Manager: A Three-Decade Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosik, J.J. The role of personal values in the charismatic leadership of corporate managers: A model and preliminary field study. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, G.; Adrodegari, F.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Exploring How Usage-Focused Business Models Enable Circular Economy through Digital Technologies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepker, D.J.; Nyberg, A.J.; Ulrich, M.D.; Wright, P.M. Planning for Future Leadership: Procedural Rationality, Formalized Succession Processes, and CEO Influence in CEO Succession Planning. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 523–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P. Managerial challenges of Industry 4.0: An empirically backed research agenda for a nascent field. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 803–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-M.; Lin, C.-P. Assessing the effects of responsible leadership and ethical conflict on behavioral intention. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 1003–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, J.; MacDonald, H.A.; Sulsky, L.M. Do Personal Values Influence the Propensity for Sustainability Actions? A Policy-Capturing Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, C.A. Personal Values as A Catalyst for Corporate Social Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 60, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, L.; Cheung, Y.H.; Herndon, N.C. For All Good Reasons: Role of Values in Organizational Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values—Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Spranger, E. Types of Men; Max Neimeyer Verlag: Halle, Germany, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. Pattern and Growth in Personality; Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Cieciuch, J.; Vecchione, M.; Davidov, E.; Fischer, R.; Beierlein, C.; Ramos, A.; Verkasalo, M.; Lonnqvist, J.-E.; Demirutku, K.; et al. Refining the Theory of Basic Individual Values. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluckhohn, C. Values and value orientations in the theory of action. In Toward a General Theory of Action; Parsons, T., Shils, E.A., Eds.; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1951; pp. 388–433. [Google Scholar]

- Črešnar, R.; Jevšenak, S. The Millennials’ Effect: How Can Their Personal Values Shape the Future Business Environment of Industry 4.0? Naše Gospod. Our Econ. 2019, 65, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, M.M.; Quaquebeke, N.V.; Dick, R.V. Two Independent Value Orientations: Ideal and Counter-Ideal Leader Values and Their Impact on Followers’ Respect for and Identification with Their Leaders. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schwartz, S.H. Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human-values? J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Value priorities and behavior: Applying a theory of integrated value. In The Psychology of Values: The Ontario Symposium; Seligman, C., Olson, J.M., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, L.; Roccas, S.; Cieciuch, J.; Schwartz, S.H. Personal values in human life. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.E.; Edmondson, A.C. When values backfire: Leadership, attribution, and disenchantment in a values-driven organization. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabic, M.; Potocan, V.; Nedelko, Z. Personal values supporting enterprises’ innovations in the creative economy. J. Knowl. Econ. 2016, 8, 1241–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsche, D.J. Personal Values: Potential Keys to Ethical Decision Making. J. Bus. Ethics 1995, 14, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, B.L. Comparing Corporate Managers’ Personal Values over Three Decades, 1967–1995. J. Bus. Ethics 1999, 20, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaro, S.J.; Klimoski, R.J. The Nature of Organizational Leadership: An Introduction. In The Nature of Organizational Leadership: Understanding the Performance Imperatives Confronting Today’s Leaders; Zaccaro, S.J., Klimoski, R.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. Business leaders’ personal values, organisational culture and market orientation. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017, 25, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grojean, M.W.; Resick, C.J.; Dickson, M.W.; Smith, D.B. Leaders, Values, and Organizational Climate: Examining Leadership Strategies for Establishing an Organizational Climate Regarding Ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 55, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogdill, R.M. Handbook of Leadership; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, J.E.; Lord, R.G.; Gardner, W.L.; Meuser, J.D.; Liden, R.C.; Hu, J. Leadership theory and research in the new millennium: Current theoretical trends and changing perspectives. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, T.; Eden, D.; Avolio, B.J.; Shamir, B. Impact of transformational leadership on follower development and performance: A field experiment. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 735–744. [Google Scholar]

- Sessa, V.; Kabacoff, R.I.; Deal, J.; Brown, H. Generational Differences in Leader Values and Leadership Behaviors. Psyhol. Manag. J. 2007, 10, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemke, R.; Raines, C.; Filipczak, B. Generations at Work: Managing the Clash of Veterans, Boomers, Xers, and Nexters in Your Workplace; AMACOM: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- DuBrin, A.J. Leadership: Research Findings, Practice, and Skills; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. The implications of transactional and transformational leadership for individual, team, and organizational development. Res. Organ. Chang. Dev. 1990, 4, 231–272. [Google Scholar]

- Griseri, P. Managing Values; Macmillan Press: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, B.Z. Another Look at the Impact of Personal and Organizational Values Congruency. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, D.Ø. The Emergence and Rise of Industry 4.0 Viewed through the Lens of Management Fashion Theory. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.G.; Dalenogare, L.S.; Ayala, N.F. Industry 4.0 technologies: Implementation patterns in manufacturing companies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 210, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingaldi, M.; Ulewicz, R. Problems with the Implementation of Industry 4.0 in Enterprises from the SME Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, R.J.; Myklebust, O. Industry 4.0 and Cyber Physical systems in a Norwegian industrial context. In Advanced Manufacturing and Automation VII; Wang, K., Wang, Y., Strandhagen, J.O., Yu, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 491–499. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Bagheri, B.; Kao, H.-A. A Cyber-Physical Systems architecture for Industry 4.0-based manufacturing systems. Manuf. Lett. 2015, 3, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roblek, V.; Meško, M.; Krapež, A. A Complex View of Industry 4.0. Sage Open 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, A.M.; Murphy, C.; Clark, J.R. A (Blurry) Vision of the Future: How Leader Rhetoric about Ultimate Goals Influences Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1544–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, S.; Berson, Y. Leaders’ Impact on Organizational Change: Bridging Theoretical and Methodological Chasms. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 13, 272–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R.S.; Munz, D.C.; Bommer, W.H. Leading from within: The Effects of Emotion Recognition and Personality on Transformational Leadership Behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, G. Leadership in the Fourth Industrial Revoulution; Stanton Chase: Dallas, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, M. Capabilities for Leadership and Management in the Digital Age; Working Futures: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Staffen, S.; Schoenwald, L. Leading in the Context of the Industrial Revolution: The Key Role of the Leader 4.0; Capgemini Group: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, L.; Benn, S. Leadership for Sustainability: An Evolution of Leadership Ability. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, E.J.; Oliver, B.L. American managers’ personal value system revisited. Acad. Manag. J. 1974, 17, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarros, J.C.; Santora, J.C. Leaders and values: A cross-cultural study. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2001, 22, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzza, J. Are You Living to Work or Working to Live? What Millennials Want in the Workplace. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Labor Stud. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, J.J.; Altman, D.G.; Rogelberg, S.G. Millennials at Work: What We Know and What We Need to Do (If Anything). J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Freeman, E.C.; Campbell, W.K. Generational Differences in Young Adults’ Life Goals, Concern for Others, and Civic Orientation, 1966–2009. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1045–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, M.J.; Ettner, L.W. Are leadership values different across generations? A comparative leadership analysis of CEOs v. MBAs. J. Manag. Dev. 2014, 33, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, M. A Study of the Innovation, Creativity, and Leadership Skills Associated with the College-Level Millennial Generation; ProQuest LLC: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.W.; Greenwood, R.A.; Murphy, J.; Edward, F. Generational Differences in the Workplace: Personal Values, Behaviors, And Popular Beliefs. J. Divers. Manag. 2009, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J.M. iGen; Simon & Schuester: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. Understanding Human Values: Individual and Societal; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ralston, D.A.; Egri, C.P.; Naoumova, I.; Treviño, L.J.; Shimizu, K.; Li, Y. An empirical test of the trichotomy of values crossvergence theory. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2020, 37, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Straub, C.; Kusyk, S. Making a life or making a living? Cross-cultural comparisons of business students’ work and life values in Canada and France. Cross Cult. Manag. 2007, 14, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriac, J.P.; Woehr, D.J.; Banister, C. Generational Differences in Work Ethic: An Examination of Measurement Equivalence across Three Cohorts. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graybill, J.O. Millennials among the Professional Workforce in Academic Libraries: Their Perspective on Leadership. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2014, 40, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper, M.P. Web surveys: A review of issues and approaches. Public Opin. Q. 2000, 64, 464–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing Construct Validity in Organizational Research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: An integrative review. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, R. Handbook of Univariate and Multivariate Data Analysis and Interpretation with SPSS; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, B.R. Feeling Like a Leader: The Emotions of Leadership; ERIC: Ipswich, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, W. Trust: The Critical Factor in Leadership. Public Manag. 2009, 38, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, R.W.; Bartelsman, E.J.; Diefenbach, S.; Franke, L.; Grunwald, A.; Helbing, D.; Hill, R.; Hilty, L.; Höjer, M.; Klauser, S.; et al. Unintended Side Effects of the Digital Transition:European Scientists’ Messages from a Proposition-Based Expert Round Table. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyc, L.; Meltzer, D.; Liu, C. Ineffective leadership and employees’ negative outcomes: The mediating effect of anxiety and depression. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2017, 24, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, K.S. Testing a Moderated Mediation Model of Transformational Leadership, Values, and Organization Change. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2020, 27, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.; Lepsinger, R. Leading change: Adapting and innovating in an uncertain world. Leadersh. Act. Publ. Center Creat. Leadersh. 2006, 26, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Brown, D.J.; Freiberg, S.J. Understanding the Dynamics of Leadership: The Role of Follower Self-Concepts in the Leader/Follower Relationship. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1999, 78, 167–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yammarino, F.J.; Dionne, S.D.; Uk Chun, J.; Dansereau, F. Leadership and levels of analysis: A state-of-the-science review. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 879–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, F.; Guarin, A.; Mora, J.; Sauza, J.; Retat, S. Learning Factory: The Path to Industry 4.0. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 9, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalva, E.; Harms, P.D.; Newman, D.A.; Gaddis, B.H.; Fraley, R.C. Narcissism and Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Review of Linear and Nonlinear Relationships. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 68, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potocan, V.; Nedelko, Z. A New Socio-economic Order: Evidence about Employees’ Values’ Influence on Corporate Social Responsibility. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2015, 32, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkesmann, M.; Wilkesmann, U. Industry 4.0-organizing routines or innovations? Vine J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2018, 48, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, K.L. Leading after the boom: Developing future leaders from a future leader’s perspective. J. Manag. Dev. 2018, 37, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Črešnar, R.; Nedelko, Z.; Jevšenak, S. Strategies and tools for knowledge management in innovation and the future industry. In The Role of Knowledge Transfer in Open Innovation; Almeida, H., Sequeira, B., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 179–202. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, N.; Walter, R. An Experience of Peer Mentoring with Student Nurses: Enhancement of Personal and Professional Growth. J. Nurs. Educ. 2000, 39, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, B.; Spencer, R.; West, J.; Rappaport, N. Expanding the reach of youth mentoring: Partnering with youth for personal growth and social change. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Z.; Qin, S.F.; Li, R.; Zou, Y.S.; Ding, G.F. Environment interaction model-driven smart products through-life design framework. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2020, 33, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P.Y.Y.; McLean, G.N.; Lien, B.Y.H.; Hsu, Y.C. Self-rated and peer-rated organizational citizenship behavior, affective commitment, and intention to leave in a Malaysian context. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, D.A.E.A. Societal-Level Versus Individual-Level Predictions of Ethical Behavior: A 48-Society Study of Collectivism and Individualism. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hisrich Robert, D.; Bucar, B.; Oztark, S. A cross-cultural comparison of business ethics: Cases of Russia, Slovenia, Turkey, and United States. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 2003, 10, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfred, F.R.; Vries, K.D. Down the Rabbit Hole of Leadership: Leadership Pathology in Everyday Life; Palgrave Macmillan: Fontainebleau, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 22.62 | 2.85 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2. Gender | 1.26 | 0.45 | −0.008 | 1 | |||||||||

| 3. Place of residence | 1.58 | 0.49 | 0.010 | 0.059 | 1 | ||||||||

| 4. Security-conformity | 3.98 | 1.01 | 0.016 | 0.159 ** | 0.086 | 1 | |||||||

| 5. Achievement-power | 4.67 | 1.02 | −0.031 | 0.010 | −0.016 | 0.378 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 6. Universalism-harmony | 3.63 | 0.93 | 0.015 | 0.212 ** | 0.064 | 0.209 ** | 0.066 | 1 | |||||

| 7. Tradition-conformity | 3.59 | 1.23 | 0.088 | -0.006 | 0.157 ** | 0.476 ** | 0.322 ** | 0.231 ** | 1 | ||||

| 8. Self-direction-stimulation | 4.28 | 0.97 | 0.020 | −0.016 | −0.044 | −0.41 | 0.229 ** | 0.118 * | −0.009 | 1 | |||

| 9. Universalism-benevolence | 5.00 | 0.87 | 0.118 * | 0.147 ** | 0.059 | 0.232 ** | 0.208 ** | 0.387 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.242 ** | 1 | ||

| 10. Universalism-tolerance | 5.26 | 0.74 | 0.019 | 0.079 | 0.054 | 0.274 ** | 0.234 ** | 0.357 ** | 0.265 ** | 0.256 ** | 0.368 ** | 1 | |

| 11. Hedonism | 4.87 | 0.88 | 0.009 | −0.015 | −0.096 | 0.149 * | 0.317 ** | 0.168 ** | 0.043 | 0.395 ** | 0.279 ** | 0.290 ** | 1 |

| 12. Leadership inclination | 3.35 | 0.94 | 0.049 | −0.101 | −0.047 | 0.312 ** | 0.585 ** | -0.171 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.223 ** | −0.007 | 0.012 | −0.104 * |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | t | β | t |

| 1. Age | 0.048 | 0.930 | 0.060 | 1.551 |

| 2. Gender | −0.098 | −1.884 | −0.061 | −1.548 |

| 3. Place of residence | −0.042 | −0.801 | −0.052 | −1.335 |

| 4. Security-conformity | 0.172 *** | 3.684 | ||

| 5. Achievement-power | 0.505 *** | 11.334 | ||

| 6. Universalism-harmony | −0.197 *** | −4.510 | ||

| 7. Tradition-conformity | 0.168 *** | 3.664 | ||

| 8. Self-Direction-stimulation | 0.224 *** | 5.182 | ||

| 9. Universalism-benevolence | −0.094 * | −2.106 | ||

| 10. Universalism-tolerance | −0.117 ** | −2.626 | ||

| 11. Hedonism | −0.091 * | −2.056 | ||

| N | 371 | 371 | ||

| F | 1.754 | 30.868 *** | ||

| R2 | 0.014 | 0.486 | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Črešnar, R.; Nedelko, Z. Understanding Future Leaders: How Are Personal Values of Generations Y and Z Tailored to Leadership in Industry 4.0? Sustainability 2020, 12, 4417. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114417

Črešnar R, Nedelko Z. Understanding Future Leaders: How Are Personal Values of Generations Y and Z Tailored to Leadership in Industry 4.0? Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4417. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114417

Chicago/Turabian StyleČrešnar, Rok, and Zlatko Nedelko. 2020. "Understanding Future Leaders: How Are Personal Values of Generations Y and Z Tailored to Leadership in Industry 4.0?" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4417. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114417

APA StyleČrešnar, R., & Nedelko, Z. (2020). Understanding Future Leaders: How Are Personal Values of Generations Y and Z Tailored to Leadership in Industry 4.0? Sustainability, 12(11), 4417. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114417