Perceived Consumer Effectiveness as A Trigger of Behavioral Spillover Effects: A path towards Recycling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background And Research Hypotheses

2.1. Recycling Behavior

Factors Linked to The Analysis of Recycling Behavior

2.2. PCE and Pro-environmental Behavior

2.3. Interventions and Strategies to Promote Sustainable Behaviors (Recycling)

2.4. Spillover among Pro-environmental Behaviors

Spillover from Simple to Complex Behaviors

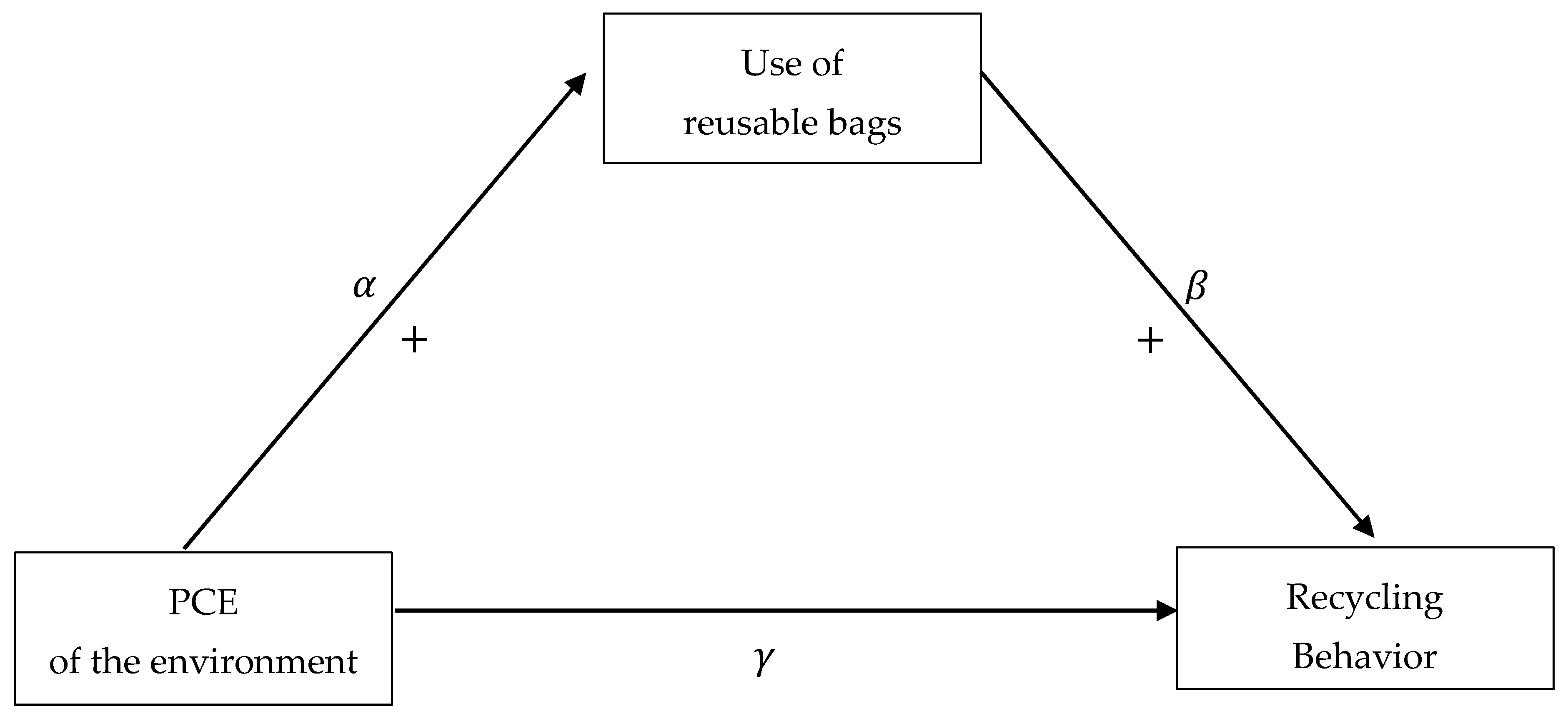

2.5. Hypotheses Formulation

Model

3. Methods

Sample, Instruments and Data Collection

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Managerial Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benton, R. Reduce, Reuse, Recycle … and Refuse. J. Macromarketing 2015, 35, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. Factors Influencing Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; Volume 39, pp. 435–473. [Google Scholar]

- Crociata, A.; Agovino, M.; Sacco, P.L. Recycling waste: Does culture matter? J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2015, 55, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, D. Household waste recycling: National survey evidence from Italy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 56, 1125–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, J.; Cherian, J.; Madansky, M.; Narayana, C. Determinants of Recycling Behavior: A Syntehsis of Research Results. J. Socio Econ. 1995, 24, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miafodzyeva, S.; Brandt, N. Recycling behaviour among householders: Synthesizing determinants via a meta-analysis. Waste Biomass Valorization 2013, 4, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.T. Self-Perception Based Strategies for Stimulating Energy Conservation. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 8, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, I.E.; Corbin, R.M. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Faith in Others as Moderators of Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1992, 11, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, C.; Fabien, D.; Lova, R.; Rodier, F. Marketing Challenges in a Turbulent Business Environment. Proc. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Wiener, J.L.J.L.; Cobb-Walgren, C.; Scholder Ellen, P.; Wiener, J.L.J.L.; Cobb-Walgren, C. The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1991, 10, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Dayal, R. Drivers of Green Purchase Intentions: Green Self-Efficacy and Perceived Consumer Effectiveness. Glob. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2017, 8, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.F.E. Determining the Characteristics of the Socially Conscious Consumer. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izagirre-Olaizola, J.; Fernández-Sainz, A.; Vicente-Molina, M.A. Internal determinants of recycling behaviour by university students: A cross-country comparative analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Crompton, T. Simple and painless? The limitations of spillover in environmental campaigning. J. Consum. Policy 2009, 32, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, H.B.; Carrico, A.R.; Weber, E.U.; Raimi, K.T.; Vandenbergh, M.P. Positive and negative spillover of pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and theoretical framework. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 29, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauren, N.; Fielding, K.S.; Smith, L.; Louis, W.R. You did, so you can and you will: Self-efficacy as a mediator of spillover from easy to more difficult pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M.; Atomic, I.; Agency, E.; Federal, T.; Commission, T. Theory of Reasoned Action/Theory of Planned Behavior. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 2007, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, P.; Ajzen, I.; Hall-box, T. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar]

- Varotto, A.; Spagnolli, A. Psychological strategies to promote household recycling. A systematic review with meta-analysis of validated field interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, C.; Hernández, B.; Cuadrado, E.; Luque, B.; Pereira, C.C.R. A multilevel perspective to explain recycling behaviour in communities. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 159, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousta, K.; Zisen, L.; Hellwig, C. Household Waste Sorting Participation in Developing Countries—A Meta-Analysis. Recycling 2020, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, J.L.; Steg, L.; van der Werff, E.; Ünal, A.B. A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemat, B.; Razzaghi, M.; Bolton, K.; Rousta, K. The Potential of Food Packaging Attributes to Influence Consumers’ Decisions to Sort Waste. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskamp, S.; Harrington, M.J.; Edwards, T.C.; Sherwood, D.L.; Okuda, S.M.; Swanson, D.C. Factors Influencing Household Recycling Behavior. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 494–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. Equal Opportunity, Unequal Results: Determinants of Household Recycling Intensity. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, J.; Ebreo, A. What Makes a Recycler? A Comparison of Recyclers and Nonrecyclers. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, G.; Pandelaere, M.; Warlop, L.; Dewitte, S. Positive cueing: Promoting sustainable consumer behavior by cueing common environmental behaviors as environmental. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2008, 25, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnear, T.C.; Taylor, J.R.; Ahmed, S.A. Ecologically Concerned Consumers—Who Are They. J. Mark. 1974, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanss, D.; Doran, R. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, E.M.; Felix, R.; Carrete, L.; Centeno, E.; Castaño, R. Green shades: A segmentation approach based on ecological consumer behavior in an emerging economy. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2015, 23, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Kalamas, M.; Laroche, M. Shades of green: Linking environmental locus of control and pro-environmental behaviors. J. Consum. Mark. 2005, 22, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehurst, G.; Afonso, C.; Gonçalves, H.M. Re-examining green purchase behaviour and the green consumer profile: New evidences. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 972–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Haley, E.; Yang, K. The Role of Organizational Perception, Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Self-efficacy in Recycling Advocacy Advertising Effectiveness. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Green Consumer in the 1990: Profile and Implications for Advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straughan, R.D.; Roberts, J.A. Environmental segmentation alternatives: A look at green consumer behavior in the new millennium. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A.; Harris, K.E. A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emekci, S. Green consumption behaviours of consumers within the scope of TPB. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.; Pereira, M.C.; Cruz, L.; Simões, P.; Barata, E. Affect and the adoption of pro-environmental behaviour: A structural model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of Green Purchase Behaviour: An Examination of Collectivism, Environmental Concern, and PCEE. Adv. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antil, J.A.; Bennett, P.D. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Socially Responsible Consumption Behavior. Conserver Soc. 1979, 51, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Antil, J.H. Socially Responsible Consumers: Profile and Implications for Public Policy. J. Macromarketing 1984, 4, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, J.G. Antecedents and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.D.; Crosby, L.A.; Taylor, J.R. Ecological Concern, Attitudes, and Social Norms in Voting Behavior. Public Opin. Q. 1986, 50, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, J.L.; Doescher, T.A. A Framework for Promoting Cooperation. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habitzreuter, A.M. To Bin or Not to Bin? The Role of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness on Sustainable Disposal Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, Technischen Universität München, München, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- Do Valle, P.O.; Rebelo, E.; Reis, E.; Menezez, J. Combining Behavioral Theories to Predict Recycling Involvement; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; Volume 37, pp. 364–396. [Google Scholar]

- Seacat, J.D.; Northrup, D. An information-motivation-behavioral skills assessment of curbside recycling behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickaël, D.; Isabelle, D.; Sébastien, M. Revue de littérature sur les techniques d’influence et de communication appliquées à la gestion des déchets. Prat. Psychol. 2014, 20, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, L.; Kanis, M. Encouraging sustainable fashion with a playful recycling system. In Proceedings of the HCI 2013—27th International British Computer Society Human Computer Interaction Conference: The Internet of Things, London, UK, 9–13 September 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermiller, C. The baby is sick/the baby is well: A test of environmental communication appeals. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Aranda, L.A.; Martínez-Fiestas, M.; Sánchez-Fernández, J. Neural effects of environmental advertising: An fMRI analysis of voice age and temporal framing. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived Greenwashing: The Interactive Effects of Green Advertising and Corporate Environmental Performance on Consumer Reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Bergquist, M.; Schultz, W.P. Spillover effects in environmental behaviors, across time and context: A review and research agenda. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Spillover processes in the development of a sustainable consumption pattern. J. Econ. Psychol. 1999, 20, 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzini, P.; Thøgersen, J. Behavioural spillover in the environmental domain: An intervention study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazar, N.; Zhong, C.-B. Do Green Products Make Us Better People? Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiefenbeck, V.; Staake, T.; Roth, K.; Sachs, O. For better or for worse? Empirical evidence of moral licensing in a behavioral energy conservation campaign. Energy Policy 2013, 57, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, I.E. The demographics of recycling and the structure of environmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baca-Motes, K.; Brown, A.; Gneezy, A.; Keenan, E.A.; Nelson, L.D. Commitment and Behavior Change: Evidence from the Field. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 39, 1070–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. Spillover of environment-friendly consumer behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, J.I.; Fraser, S.C. Compliance Without Pressure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1966, 4, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Noblet, C. Does green consumerism increase the acceptance of wind power? Energy Policy 2012, 51, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrico, A.R.; Raimi, K.T.; Truelove, H.B.; Eby, B. Putting Your Money Where Your Mouth Is: An Experimental Test of Pro-Environmental Spillover From Reducing Meat Consumption to Monetary Donations. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 723–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margetts, E.A.; Kashima, Y. Spillover between pro-environmental behaviours: The role of resources and perceived similarity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 49, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.J. Task Complexity: A Review and Analysis. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.E. Task complexity: Definition of the construct. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1986, 37, 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G. A general measure of ecological behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Kwon, S.Y. Spillover from past recycling to green apparel shopping behavior: The role of environmental concern and anticipated guilt. Fash. Text. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, H.B.; Yeung, K.L.; Carrico, A.R.; Gillis, A.J.; Raimi, K.T. From plastic bottle recycling to policy support: An experimental test of pro-environmental spillover. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior: EBSCOhost. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 563, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. The Influence of Individualism, Collectivism, and Locus of Control on Environmental Beliefs and Behavior. J. Public Policy Mark. 2001, 20, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Measurement and determinants of environmentally significant consumer behavior. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, D.J. Self-Perception: An Alternative Interpretation of Cognitive Dissonance Phenomena. Psychol. Rev. 1967, 74, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Trost, M.R.; Newsom, J.T. Preference for Consistency: The Development of a Valid Measure and the Discovery of Surprising Behavioral Implications. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, F.; Hansstein, F.V. Assessing the intention-behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: The case of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, S.; Ellis, D. Creativity in marketing communication to overcome barriers to organic produce purchases: The case of a developing nation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlau, W.; Hirsch, D. Sustainable Consumption and the Attitude-Behaviour-Gap Phenomenon—Causes and Measurements towards a Sustainable Development. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2015, 6, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attari, S.Z. Saving energy: I’ll do the easy thing, you do the hard thing. In Proceedings of the Behavior Energy Climate Change Conference, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 31 May–2 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, J.; Muralidharan, S. What triggers young Millennials to purchase eco-friendly products?: The interrelationships among knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness, and environmental concern. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffman, A.H.; Van Der Werff, B.R.; Henning, J.B.; Watrous-Rodriguez, K. When do recycling attitudes predict recycling? An investigation of self-reported versus observed behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S. Environmental concern, attitude toward frugality, and ease of behavior as determinants of pro-environmental behavior intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Items | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Behavior (recycling) | I separate organic materials from recyclable ones. | 4: Very frequently; 1: Never |

| Independent Environmental PCE | As an individual, I feel I cannot do a lot to care for the environment. | 4: Totally agree; 1: Totally disagree |

| Mediator Behavior (use of reusable bags) | How often do you use reusable bags for shopping? | 4: Very frequently; 1: Never |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||

| Recycling behavior | 2.90 | 1.13 | 1270 |

| Independent variable | |||

| Environmental PCE | 2.92 | 1.07 | 1273 |

| I cannot do a lot for the environment | |||

| Mediator variable | |||

| Reusing behavior (use of reusable bags) | 2.12 | 0.92 | 1286 |

| Sociodemographics | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Age | 1285 | ||

| (18–22) | 169 | 13.2 | |

| (23–27) | 153 | 11.9 | |

| (28–32) | 136 | 10.6 | |

| (33–37) | 140 | 10.9 | |

| (38–42) | 124 | 9.6 | |

| (43–47) | 124 | 9.6 | |

| (48–52) | 109 | 8.5 | |

| (53–57) | 91 | 7.1 | |

| (58–62) | 79 | 6.1 | |

| (63–67) | 66 | 5.1 | |

| (68 or over) | 94 | 7.3 | |

| Gender | 1285 | ||

| Male | 509 | 39.6 | |

| Female | 777 | 60.4 | |

| Marital Status | 1286 | ||

| Single | 419 | 32.6 | |

| Married | 350 | 27.2 | |

| Living together | 401 | 31.2 | |

| Divorced | 61 | 4.7 | |

| Widow/Widower | 55 | 4.3 | |

| Level of Education | 1286 | ||

| Elementary school | 296 | 23.6 | |

| High school | 563 | 44.9 | |

| Technical education | 198 | 15.8 | |

| Undergraduate program | 169 | 13.5 | |

| Postgraduate studies | 29 | 2.3 |

| Effects | Coefficient | SE | t | p Values | Bootstrapped 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Level | Upper Level | |||||

| Direct effects | ||||||

| Environmental PCE -> Use of reusable bags | −0.051 | 0.024 | −2.127 | 0.034 | ||

| Use of reusable bags -> Recycling behavior | 0.146 | 0.034 | 4.236 | 0.000 | ||

| Environmental PCE -> Recycling behavior | −0.006 | 0.029 | −0.190 | 0.849 | ||

| Indirect effects | ||||||

| Environmental PCE -> Use of reusable bags -> Recycling behavior | −0.007 | 0.004 | −0.017 | −0.001 | ||

| Total effects | ||||||

| Environmental PCE -> Recycling behavior | −0.013 | 0.029 | −0.442 | 0.659 | ||

| Control variables | ||||||

| Age | 0.042 | 0.010 | 4.090 | 0.000 | ||

| Gender | −0.065 | 0.065 | −1.005 | 0.315 | ||

| Household size | −0.004 | 0.021 | −0.180 | 0.857 | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arias, C.; Trujillo, C.A. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness as A Trigger of Behavioral Spillover Effects: A path towards Recycling. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114348

Arias C, Trujillo CA. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness as A Trigger of Behavioral Spillover Effects: A path towards Recycling. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114348

Chicago/Turabian StyleArias, Claudia, and Carlos A. Trujillo. 2020. "Perceived Consumer Effectiveness as A Trigger of Behavioral Spillover Effects: A path towards Recycling" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114348

APA StyleArias, C., & Trujillo, C. A. (2020). Perceived Consumer Effectiveness as A Trigger of Behavioral Spillover Effects: A path towards Recycling. Sustainability, 12(11), 4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114348