E-Mentoring in Higher Education: A Structured Literature Review and Implications for Future Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

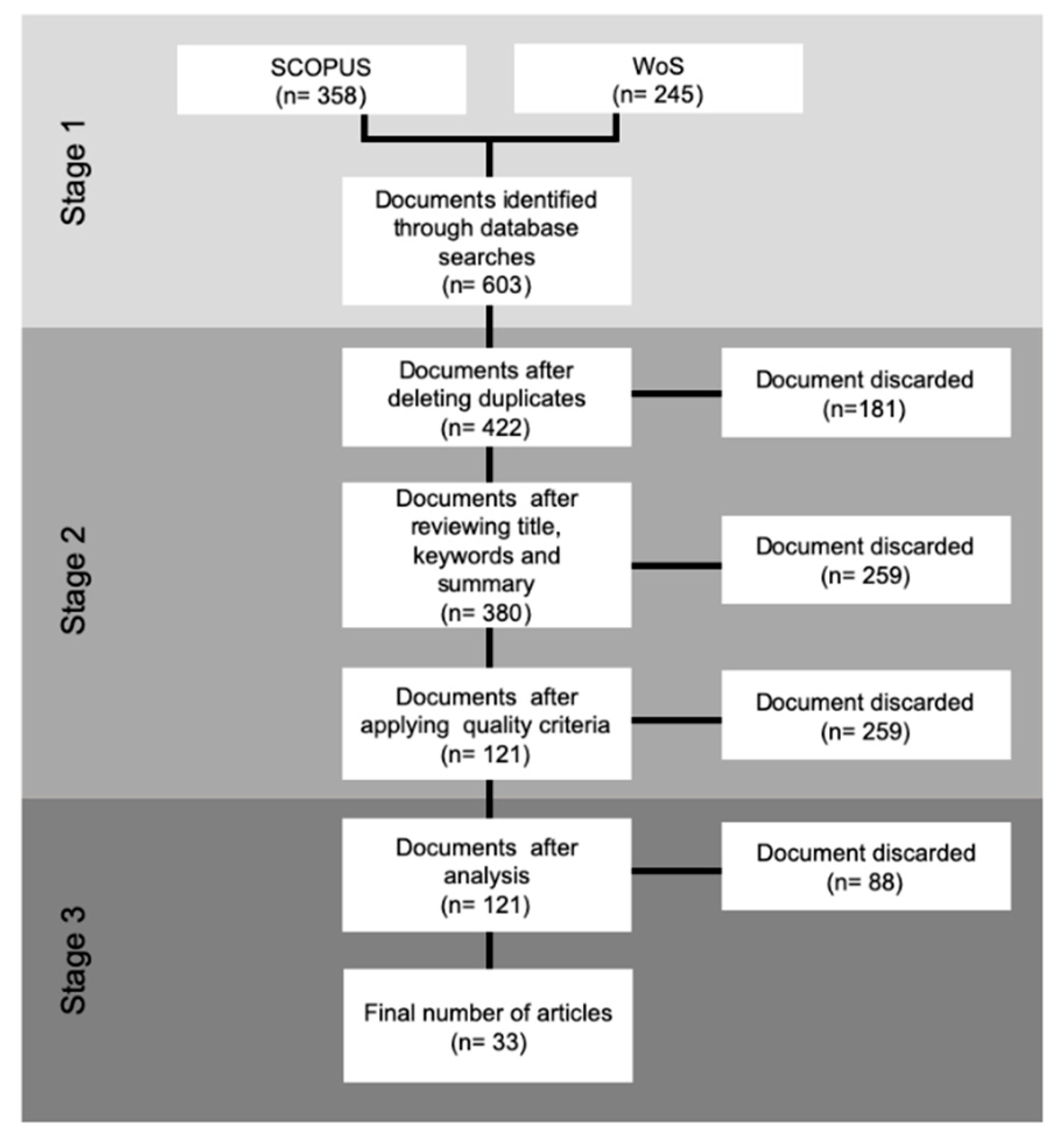

2. Method

2.1. Research Questions

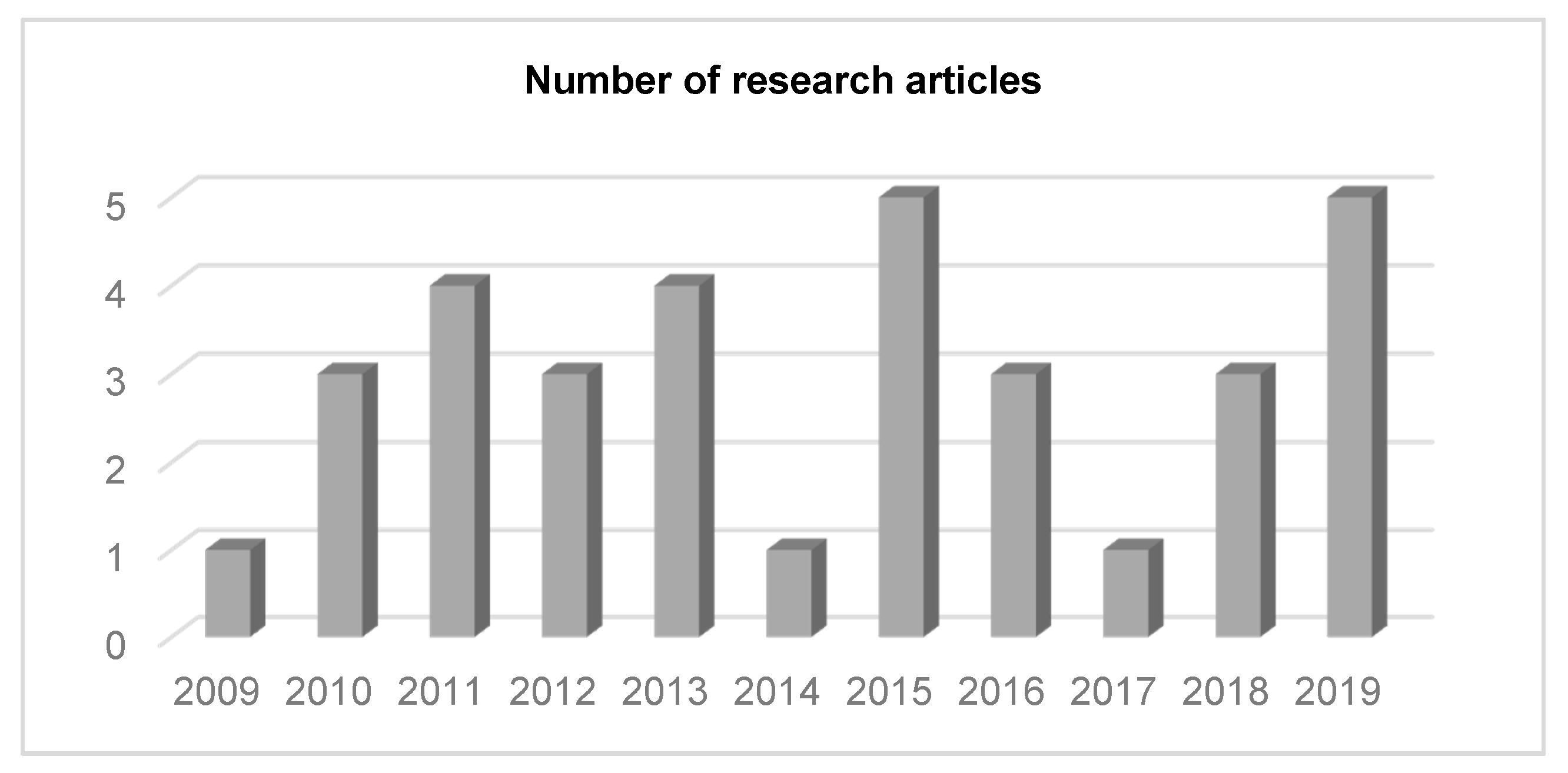

- MQ1. What has been the evolution of the number of research articles in e-mentoring in higher education since 2009?

- MQ2. Who are the prominent authors in e-mentoring in higher education?

- MQ3. What media are most frequently used to publish the results of research in e-mentoring programs in higher education?

- MQ4. Which data analysis method is used most frequently e-mentoring programs in higher education?

- RQ1. What areas are being developed with the application of an e-mentoring program in higher education?

- RQ2. What are the characteristics of e-mentoring programs in higher education?

- RQ3. How are e-mentoring programs in higher education evaluated?

- RQ4. What are the indicators of effectiveness of e-mentoring programs in higher education?

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Search Approach

- Are these databases relevant in this field of research and only provide quality research articles?

- Do these databases allow for similar or equal search strings and logical expressions to perform the search process?

- Are these databases accessible by the institution where the review is carried out or by the associations of which the authors are members?

- Do the databases allow searches to be conducted across the entire article or just in specific fields?

- Are the databases relevant and include only proven quality articles and documents?

2.4. Search Strings Used

3. Results

3.1. Mapping Results

- The approach taken by Rodrigues Reali et al. [37] was not as specific as in the quantitative approach reviewed [7,20,39]. These authors [37] used this approach to determine and improve the mentoring research questions for their investigation. They began by observing the virtual mentoring tendencies of different program types and their academic benefits.

3.2. SLR Results

4. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Marco de Competencias de los Docentes en Materia de TIC UNESCO—UNESCO Digital Library. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000371024 (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Headlam-Wells, J.; Gosland, J.; Craig, J. “There’s magic in the web”: E-Mentoring for women’s career development. Career Dev. Int. 2005, 10, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.; Carpenter, C. Electronic mentoring: An innovative approach to providing clinical support. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2009, 16, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Janasz, S.C.; Godshalk, M.V. The role of e-mentoring in protégés’. Learning and satisfaction. Group Org. Manag. 2013, 38, 743–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, A.R.; Cotton, J.; Neely, A.D. E-mentoring: A model and review of the literature. AIS Trans. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2017, 9, 220–242. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/thci/vol9/iss3/3 (accessed on 24 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Crisp, G. Promising practices and programs: Current efforts and future directions. New Dir. Commun. Coll. 2016, 2016, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, W.M. From E-mentoring to blended mentoring: Increasing students’ developmental initiation and mentors’ satisfaction. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2011, 10, 606–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obura, T.; Brant, W.E.; Miller, F.; Parboosingh, I.J. Participating in a community of learners enhances resident perceptions of learning in an e-mentoring program: Proof of concept. BMC Med. Educ. 2011, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briscoe, P. Virtual mentor partnerships between practicing and preservice teachers. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 2019, 8, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, F. Towards the study of actor training in an age of globalised digital technology. Theatr. Dance Perform. Train. 2015, 6, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.L.; Kim, J. E-mentoring in online course projects: Description of an e-mentoring scheme. Int. J. Evid. Based Coach. Mentor. 2011, 9, 80–95. Available online: http://ijebcm.brookes.ac.uk/documents/vol09issue2-paper-06.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2020).

- Owen, H.; Whalley, R.; Dunmill, M.; Eccles, H. Social impact in personalised virtual professional development pathways. J. Educators Online 2018, 15, 1–11. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1168953.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- ChanLin, L.J. Students’ involvement and community support for service engagement in online tutoring. J. Educ. Med. Libr. Sci. 2016, 53, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco-Giraldo, H.; Torrecilla Sánchez, E.M.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. Utilizing technological ecosystems to support graduate students in their practicum experiences. In TEEM’18 Doctoral Consortium, Proceedings of the TEEM’18: Sixth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, Salamanca, Spain, 24–26 October 2018; García Peñalvo, F.J., Ed.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligadu, C.; Anthony, P. E-mentoring ‘MentorTokou’: Support for mentors and mentees during the practicum. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 186, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haran, V.V.; Jeyaraj, A. Organizational e-mentoring and learning: An exploratory study. IRMJ 2019, 32, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabalza, M.A. El prácticum y las prácticas externas en la formación universitaria. Revista Prácticum 2017, 1, 1–23. Available online: https://revistapracticum.com/index.php/iop/article/view/15/42 (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Mareque, M.; De Prada, E. Evaluación de las competencias profesionales a través de las prácticas externas: Incidencia de la creatividad. Revista de Investigación Educativa 2018, 36, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Janasz, S.C.; Ensher, E.A.; Heun, C. Virtual relationships and real benefits: Using e-mentoring to connect business students with practicing managers. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2008, 16, 394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, A.; Kogo, C. Attributes of good e-learning mentors according to learners. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 6, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, F.J.; Locander, W.B. Advancing Workplace spiritual development: A dyadic mentoring approach. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal Ledo, M.; Oramas Díaz, J.; Borroto Cruz, R. Revisiones sistemáticas. Educación Médica Superior 2015, 29, 198–207. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/ems/v29n1/ems19115.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2020).

- Ramírez-Montoya, M.S.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. Co-Creación e innovación abierta: Revisión sistemática de literatura. Comunicar 2018, 54, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F.J. Revisiones y mapeos sistemáticos de literatura. In Recursos Docentes de la Asignatura Procesos y Métodos de Modelado Para la Ingeniería web y web Semántica; Procesos y métodos de modelado para la ingeniería web y web semántica. Curso 2018–2019. Recursos de la asignatura procesos y métodos de modelado para la ingeniería web y web semántica del máster universitario en sistemas inteligentes de la Universidad de Salamanca; Grupo GRIAL, Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, España, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2019, October 14). Thesaurus: Mentoring. Available online: http://vocabularies.unesco.org/browser/thesaurus/en/page/?uri=http://vocabularies.unesco.org/thesaurus/concept17109 (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- UNESCO. (2006, May 23). Thesaurus: Higher Education. Available online: http://vocabularies.unesco.org/browser/thesaurus/en/page/?uri=http://vocabularies.unesco.org/thesaurus/concept1485 (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- UNESCO. (2006, May 23). Thesaurus: Internships. Available online: http://vocabularies.unesco.org/browser/thesaurus/en/page/concept2577 (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Zhu, J.; Liu, F.; Liu, W. The Secrets behind Web of Science’s DOI Search. Scientometrics 2019, 119, 1745–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera Eguía, R. ¿Revisión sistemática, revisión narrativa o meta-análisis? Revista de la Sociedad Española del Dolor 2014, 21, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullington, J.S.; Boylston, S.D. Strengthening the Profession, Assuring Our Future: ACRL’s New Member Mentoring Program Pairs Library Leaders with New Professionals. Coll. Res. Libr. News 2010, 62, 430–452. Available online: https://crln.acrl.org/index.php/crlnews/article/view/20883/25660 (accessed on 19 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- DiRenzo, M.S.; Linnehan, F.; Shao, P.; Rosenberg, W.L. A moderated mediation model of e-mentoring. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukakis, S.; Koutidou, E.; Aspasia, A. Designing an E-Mentoring Program for Supporting Teachers’ Training. In Proceedings of the 4th South-East Europe Design Automation, Computer Engineering, Piraeus, Greece, 20–22 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farheen, J.; Dixit, S. E-mentoring system application. In IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud; IEEE: Palladam, India, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainer, E.H.; Kalyanasundaram, A.; Herbsleb, J.D. E-mentoring for software engineering: A socio-technical perspective. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACM 39th International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering Education and Training Track (ICSE-SEET), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 20–28 May 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, C.N.; Jayatilleke, B.G.; Fernando, S.; Kulasekere, C.; Lamontagne, M.D.; Ekanayake, M.B.; Thaiyamuthu, T. Developing Online Tutors and Mentors in Sri Lanka through a Community Building Model: Predictors of Satisfaction; IEEE: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Reali, A.; Simões Tancredi, R.; Nicoletti Mizukami, M. Professional knowledge of teaching and the online mentoring program: A case study in the brazilian educational context. In the Wiley International Handbook of Mentoring; Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Medford, MA, USA, 2010; Volume 5, pp. 261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Golubski, P.M. Utilizing virtual environments for the creation and management of an e-mentoring initiative. In Pedagogical and Andragogical Teaching and Learning with Information Communication Technologies; IG Global: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Venis, L. E-Mentoring the Individual Writer within a Global Creative Community. Available online: www.igi-global.com/chapter/mentoring-individual-writer-within-global/38028 (accessed on 4 May 2020). [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kumar, K. E-mentoring Alternative Paradigm for Entrepreneurial Aptitude Development. Acad. of Entrep. J. 2019, 25, 1–12. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/ementoring-alternative-paradigm-for-entrepreneurial-aptitude-development-8067.html (accessed on 28 February 2020).

- Khan, R.; Gogos, A. Online Mentoring for biotechnology graduate students: An industry-academia partnership. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2013, 17, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.J.; Whiteman, R.S.; Crow, G.M. Technology’s role in fostering transformational educator mentoring. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 2013, 2, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, K.; Doyle, N.; Ryan, C. The Nature, perception, and impact of e-mentoring on post-professional occupational therapy doctoral students. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2015, 29, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, M.; Stewart, J.; Van Gorder, K. Using methodological triangulation to examine the effectiveness of a mentoring program for online instructors. Distance Educ. 2015, 36, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-González, J.R. Mixed methods: Lessons learned from five cases of doctoral theses. In TEEM’19 Implementation of Qualitative and Mix Methods Researches, Proceedings of the TEEM’19: Seventh International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, León, Spain, 16–18 October 2019; Conde González, M., Rodríguez Sedano, F.J., Fernández Llamas, C., García Peñalvo, F.J., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, N.; Jacobs, K.; Ryan, C. Faculty mentors’ perspectives on e-mentoring post-professional occupational therapy doctoral students. Occup. Ther. Int. 2016, 23, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.G.; Niemi, A.D.; Roudkovski, M. Implementing an industrial mentoring program to enhance student motivation and retention. In Corporate Member Council Industry Speaker & Best Paper Recognition; ASEE: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Greindl, T.; Schirner, S.; Albert Ziegler, H.S. The Effectiveness of a One-Year Web-Based Mentoring Program for Girls in Stem. Web Based Communities and Social Media; Elsevier: Prague, Czech Republic, 2013; Volume 69, pp. 408–418. [Google Scholar]

- Risquez, A.; Sánchez-García, M. The jury is still out: Psychoemotional support in peer e-mentoring for transition to university. Internet High. Educ. 2012, 15, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kahraman, M.; Abdullah, K. E-mentoring for professional development of pre-service teachers: A case study. Turkish Online J. Distance Educ. 2016, 17, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuankaew, P.; Temdee, P. Determining of compatible different attributes for online mentoring model. In Information Theory and Aerospace & Electronics Systems (VITAE); IEEE: Aalborg, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, H. Making the Most of mobility: Virtual mentoring and education practitioner professional development. Res. Learn. Technol. 2015, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrecilla Sánchez, E.M.; Rodríguez Conde, M.J.; Herrera García, M.E.; Martín Izard, J.F. Evaluación de Calidad de un Proceso de Tutoría de Titulación Universitaria: La Perspectiva del Estudiante de Nuevo Ingreso en Educación. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía 2013, 24, 79–99. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3382/338230794006.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, D.; Kirkpatrick, J. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels, 3rd ed.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, T.M.; Lee, C.N. Advocate-mentoring: A communicative response to diversity in higher education. Commun. Educ. 2019, 68, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argente-Linares, E.; Pérez-López, M.; Ordóñez-Solana, C. Practical experience of blended mentoring in higher education. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2016, 24, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F.J. Education in Knowledge Society: A new PhD Programme approach. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality (TEEM’13), Salamanca, Spain, 14–15 November 2013; García-Peñalvo, F.J., Ed.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F.J. Formación en la sociedad del conocimiento, un programa de doctorado con una perspectiva interdisciplinar. Educ. Knowl. Soc. 2014, 15, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de España. Real Decreto 99/2011, de 28 de Enero, por el que se Regulan las Enseñanzas Oficiales de Doctorado. In Ministerio de Educación; Gobierno de España, 2011; pp. 13909–13926. Available online: https://goo.gl/imEsz6 (accessed on 20 May 2020).

| Inclusion criteria |

| IC1. Related to e-mentoring programs applied in higher education. |

| IC2. Includes concrete and verifiable empirical research. |

| IC3. Published after a peer review process. |

| IC4. Written in English. |

| IC5. Published in high-quality (and/or impact factor) journals. |

| IC6. Research papers with quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches applied. |

| Exclusion criteria |

| EC1. Not related to specific e-mentoring programs in higher education. |

| EC2. Do not include concrete and verifiable empirical research. |

| EC3. Did not undergo a peer review process. |

| EC4. We’re not published in high-quality (and/or impact factor) journals. |

| EC5. Did not use quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods approaches. |

| Questions |

|---|

|

| Descriptor for Studies of Educational Sciences | Descriptor definition | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|

| E-Mentoring [25] | Mentoring using a computer-mediated relationship between a more skilled individual who is the mentor, and a lesser skilled individual who is the mentee. | Virtual mentoring, online mentoring, electronic mentoring, distance mentoring, mentoring on the internet, mentoring through the internet, Telementoring, internet mentoring, cybermentoring, virtual tutoring, online tutoring. |

| Higher education [26] | It is taught at universities, colleges or technical training academies. The teaching offered by higher education is at the professional level. | University, college, graduate school, tertiary school. |

| Internship [27] | It is a training experience that allows students to apply and test the knowledge they have acquired during their career, as well as to develop the skills necessary to succeed in the professional world. | Practicum, apprenticeship. |

| Source | Research Terms |

|---|---|

| SCOPUS | Combination 1 TITLE-ABS-KEY (“ e-mentoring ” AND “ program ” AND “ highereducation ”) |

| Combination 2 TITLE-ABS-KEY (“ e-mentoring ” AND “ program ” AND “ university ”) | |

| Combination 3 TITLE-ABS-KEY (“e-mentoring” OR “virtual mentoring” OR “online mentoring”) AND (“higher education” OR “university”) AND (“program”) AND (“internship” OR “practice” OR “apprenticeship”) AND (LIMIT TO (DOCTYPE, “cp”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT -TO (DOCTYPE, “ch”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “re”))AND (LIMIT TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) | |

| WoS | Combination 1 TOPIC: (“e-mentoring”) AND TOPIC (“program*”) AND TOPIC: (“higher education”) |

| Combination 2 TOPIC: (“e-mentoring”) AND TOPIC (“program*”) AND TOPIC: (“university”) | |

| Combination 3 TOPIC: (“e-mentoring”) OR TITLE: (“virtual mentoring”) OR TITLE: (“online mentoring”) AND TITLE: (“higher education”) OR TITLE: (“university”) AND TITLE: (“program*”) AND TITLE: (“internship”) |

| Source | Research Terms | Filtered Results | Duplicate Results | Results without Duplicate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCOPUS | Combination 1 | 121 | 0 | 121 |

| Combination 2 | 137 | 112 | 25 | |

| Combination 3 | 100 | 44 | 56 | |

| Total | 358 | 156 | 202 | |

| WoS | Combination 1 | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| Combination 2 | 20 | 7 | 13 | |

| Combination 3 | 211 | 18 | 193 | |

| Total | 245 | 25 | 220 | |

| Total documents | 603 | 181 | 422 |

| Author | Year | Publication Type | Subject |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stewart, S., and Carpenter, C. | 2009 | Article | Describes the implementation and evaluation of a pilot e-mentoring program to address the need for support of physical therapists working in rural positions in British Colombia, Canada. |

| Rodrigues Reali, A., Simões Tancredi R., and Nicoletti Mizukami, M. | 2010 | Book Chapter | Analyzes the development phases of the Online Mentoring Program (OMP) from the Federal University of São Carlos, Brazil. |

| DiRenzo M.S., Linnehan F., Shao P., and Rosenberg W.L. | 2010 | Article | Model of electronic mentoring (e-mentoring) from Drexel University, USA. |

| Venis L. | 2010 | Book Chapter | Individualized feedback and e-mentoring program from UCLA Extension, USA. |

| Murphy, W. M. | 2011 | Article | Explores e-mentoring in the context of student development as a tool for increasing mentees’ propensity to initiate developmental relationships from Northern Illinois University, USA. |

| Obura T., Brant W.E., Miller F., and Parboosingh I.J. | 2011 | Article | Analyses information about an e-mentoring pilot was offered to 10 Radiology residents in the Aga Khan University Postgraduate Medical Education Program. Kenya. |

| Golubski, P.M. | 2011 | Book Chapter | E-mentoring initiative conducted through virtual and Web 2.0. at Carnegie Mellon University, USA |

| Williams, S. L., and Kim, J. | 2011 | Article | Explains the structure and process of an e-mentoring system designed for an online Master’s degree at Illinois University, Carnegie Mellon, USA. |

| Risquez, A., and Sánchez-García, M | 2012 | Article | Investigates how emotionally peer electronic mentoring program was implemented at Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Spain |

| Green, M.G., Niemi A.D., and Roudkovski, M. | 2012 | Conference Paper | Details the logistics and challenges of starting up an e-mentoring program created to contribute with students’ experiences at LeTourneau University, USA. |

| Gunawardena, C., Jayatilleke, B., Fernando, S., Kulasekere, C., Lamontagne, M., Ekanayake, M., and Thaiyamuthu, T | 2012 | Conference Paper | Results of a e- tutor mentor program based on WisCom model using Moodle platform at University of Colombo School of Computing (UCSC), Sir Lanka. |

| Butler, A. J., Whiteman, R. S., and Crow, G. M | 2013 | Article | Discusses the pros and inconveniencies of e-mentoring programs in the education field at the University of Wisconsin, USA. |

| De Janasz, S., and Godshalk, V. M | 2013 | Article | Examine the import of a e-mentoring program at Pennsylvania University, USA, recognizing the inputs of mentoring relationships and learning satisfaction. |

| Greindl, T., Schirner, S., and Albert Ziegler, H. S. | 2013 | Conference Paper | Recognizes the activities and contents related to CyberMentor e-mentoring program developed to measure the STEM characteristics of girls at the University of Regensburg, Germany. |

| Khan, R., and Gogos, A. | 2013 | Article | Implementation or a e-mentoring program at Maryland University, USA, that help master’s students in biotechnology to increase and master synergistic processes in the area of knowledge. |

| Nuankaew P., and Temdee, P. | 2014 | Conference Paper | Proposes specific features for an online mentoring program. The study was applied to 588 students of the Faculty of Information and Technology of Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University, Thailand. |

| Jacobs, K., Doyle, N., and Ryan, C. | 2015 | Article | Investigates the perception and impact of the e-mentoring experiences of 29 graduate students from an online post-doctoral program in Occupational Therapy at Boston University, USA. |

| Nuankaew, P., and Temdee, P. | 2015 | Article | Recognizes the different elements that are compatible for an e-mentoring program, based on the assumption that the mentor and the mentee can work successfully not only on some common attributes between them, but also on some different attributes that are compatible between them. The study of the Program was done with Mae Fah Luang University, Phayao University, Chiang Rai Rajabhat University and Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University, Thailand. |

| Drouin, M., Stewart, J., and Van Gorder, K. | 2015 | Article | Using mixed methods, the article examines the effectiveness of an e-mentoring program designed to logistically support students with their professors, in order to increase success rates in virtual programs at the university of Indiana and Purdue University, USA. |

| Ligadu, C., and Anthony, P. | 2015 | Article | MentorTokou is an e-mentoring tool that has been developed to encourage and provide mentoring to the students of psychology and education programs at the University of Sabah, Malaysia. |

| Owen, H.D. | 2015 | Article | Outline a virtual learning and professional development program offered at Te Wānanga O Aotearoa college for indigenous people, New Zealand, recognizing the benefits of Communities of Practice (CoP) online as successful platforms to provide mentoring. |

| Kahraman, M., and Abdullah, K. | 2016 | Article | Focused on supporting the professional development of undergraduate students, postgraduate students and graduates from the department of Computer Education and Instructional Technologies at Anadolu University, Turkey. An e-mentoring document was developed that recognized the different phases of the program and displayed all the data from semi-structured interviews with participants. |

| Doyle, N., Jacobs, K., and Ryan, C. | 2016 | Article | Investigates the different perspectives of e-mentoring in a program designed for post-professional occupational therapy students from the Boston University Sargent College, USA. |

| ChanLin, L. J. | 2016 | Article | Explores the responses of students who have participated in an e-mentoring program and collects all the feedback and learning experiences from a program established at a university in northern Taiwan. |

| Trainer, E. H., Kalyanasundaram, A., and Herbsleb, J. D | 2017 | Conference Paper | Collects information from the FOSS virtual mentoring program designed for students at Carnegie Mellon University, USA, who want to develop and achieve academically related job opportunities. |

| Tominaga, A., and Kogo, C. | 2018 | Article | Identify the key success factors for e-mentoring and recognize the impact of a virtual mentoring program with students at a university in Japan. |

| Tinoco-Giraldo. H., Torrecilla-Sánchez. E. M., and García-Peñalvo. F.J. | 2018 | Conference Paper | Offers an e-mentoring program designed for students in academic practices and that can be used in different educational programs. The pilot of the program was carried out in a Colombian University. |

| Owen, H.D., Whalley, R., Dunmill, M., and Eccles, H | 2018 | Article | Presents a virtual academic mentoring program for the professional development of learning, recognizes the value that the participants give to the program, and is directed to students of education from indigenous communities at the Wānanga O Aotearoa College, New Zealand. |

| Farheen, J., and Dixit, S. | 2018 | Conference Paper | Shows an application made exclusively for a virtual education program that supports students at a university in North India. |

| Singh P., and Kumar K. | 2019 | Article | Recognizes an effective use of virtual mentoring processes and identifies key skills for entrepreneurial development of participants at a university in the state of Rajasthan, north-west part of India. |

| Haran, V. V., and Jeyaraj, A. | 2019 | Article | Explores an e-mentoring program applied at the University of Urbana-Champaign, USA, with some organizational settings, emphasizing how learning acts as career support in addition to psychosocial and role modeling to support learning of new skills and how learning increases organizational engagement of mentees. |

| Doukakis, S., Koutidou, E., and Aspasia, O | 2019 | Conference Paper | Debate on key aspects of e-mentoring, in practical and academic contexts, identifies objectives, role models, and mentoring modalities to be applied in Greek universities. |

| Briscoe, P. | 2019 | Article | Assess the benefit of virtual mentoring between student teacher candidates and practicing teachers and recognizes the experience that mentors can offer to teacher candidates. The process was developed for the students of the College of Education at Niagara University, USA. |

| Author | Number of Publications |

|---|---|

| Nuankaew P.; Temdee P.; Owen, H.D. | 2 |

| Stewart, S.; Carpenter, C; Rodrigues Reali, A.; Simões Tancredi R; Mizukami; Nicoletti Mizukami, M; DiRenzo M.S.; Linnehan F.; Shao P.; Rosenberg W; Venis, L.; Murphy, W. M.; Obura T.; Brant W.E.; Miller F.; Parboosingh I.; Golubski, P.M; Williams, S. L.; Kim, J.; Risquez, A; Sánchez-García, M; Green, M.G.; Niemi A.D.; Roudkovski, M.; Gunawardena, C.; Jayatilleke, B.; Fernando, S.; Kulasekere, C.; Lamontagne, M.; Ekanayake, M.; Thaiyamuthu, T.; Butler, A. J.; Whiteman, R. S.; Crow, G. M.; Greindl, T.; Schirner, S.; Albert Ziegler, H. S.; Khan, R.; Gogos, A.; Jacobs, K.; Doyle, N.; Ryan, C.; Drouin, M.; Stewart, J.; Van Gorder, K.; Ligadu, C.; Anthony, P.; Kahraman, M.; Abdullah, K.; Doyle, N.; Jacobs, K.; Ryan, C.; ChanLin, L. J.; Trainer, E. H.; Kalyanasundaram, A.; Herbsleb, J. D.; Tominaga, A.; Kogo, C; Tinoco-Giraldo. H.; Torrecilla-Sánchez. E. M.; García-Peñalvo. F.J; Whalley, R.; Dunmill, M.; Eccles, H.; Farheen, J.; Dixit, S.; Singh P.; Kumar, K.; Haran, V. V.; Jeyaraj, A.; Doukakis, S.; Koutidou, E.; Aspasia, O.; Briscoe, P. | 1 |

| Journal | SJR2019 | Country | Subject Area | Nº-P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation | 0.19 | United Kingdom | Health Professions | 1 |

| Journal of Vocational Behavior | 2.16 | United States | Business, Management and Accounting | 1 |

| Cadernos de Pesquisa | 0.23 | Brazil | Social Science-Education | 1 |

| Academy of Management Learning and Education | 2.03 | United States | Business, Management and Accounting | 1 |

| BMC Medical Education | 0.80 | United Kingdom | Medicine | 1 |

| International Journal of Evidence based Coaching and Mentoring | 0.30 | United Kingdom | Business, Management and Accounting | 1 |

| Internet and Higher Education | 3.31 | United Kingdom | Computer Science | 1 |

| International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education | 0.43 | United Kingdom | Social Science- Education | 2 |

| Group and Organization Management | 1.77 | United States | Arts and Humanities | 1 |

| Online Learning (formerly Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network) | 0.55 | United States | Computer Science | 1 |

| Occupational Therapy in Health Care | 0.23 | United States | Health Professions | 1 |

| Wireless Personal Communications | 0.25 | Netherlands | Computer Science | 1 |

| Distance Education | 0.97 | United Kingdom | Social Science- Education | 1 |

| Research in Learning Technology | 0.58 | United Kingdom | Computer Science | 1 |

| Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education | 0.27 | Turkey | Social Science- Education | 1 |

| Occupational Therapy International | 0.31 | Egypt | Health Professions | 1 |

| Journal of Educational Media and Library Sciences | 0.26 | Taiwan | Arts and Humanities | 1 |

| Universal Journal of Educational Research | 0.19 | United States | Social Science- Education | 1 |

| Journal of Educators Online | 0.21 | United States | Social Science- Education | 1 |

| Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal | 0.20 | United States | Business, Management and Accounting | 1 |

| Information Resources Management Journal | 0.18 | United States | Business, Management and Accounting | 1 |

| Journal | Year Publication | SCOPUS | JCR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | SJR | H Index | Citescore Rank | Q | Index | Citescore Rank | ||

| International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation | 2009 | 3 | 0.205 | 21 | 13/65 | |||

| Journal of Vocational Behavior | 2010 | 1 | 1.687 | 18 | 116/682 | 1 | 2.604 | 17/63 |

| Cadernos de Pesquisa | 2010 | 3 | 0.155 | 13 | 18/26 | |||

| Academy of Management Learning and Education | 2011 | 1 | 2.188 | 63 | 130/531 | 1 | 1.36 | 30/224 |

| BMC Medical Education | 2011 | 2 | 0.632 | 54 | 29/361 | 1 | 1.66 | 1/206 |

| International Journal of Evidence based Coaching and Mentoring | 2011 | 4 | 0.65 | 82 | 67/89 | |||

| Internet and Higher Education | 2012 | 1 | 1.997 | 75 | 29/434 | 1 | 2.47 | 15/219 |

| International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching inEducation | 2013 | 2 | 0.651 | 12 | 10/20 | |||

| Group and Organization Management | 2013 | 1 | 1.313 | 74 | 18/223 | 2 | 1.400 | 27/75 |

| Online Learning (formerly Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network) | 2013 | 3 | 0.284 | 42 | 60/85 | |||

| Occupational Therapy in Health Care | 2015 | 3 | 0.22 | 20 | 11/70 | |||

| Wireless Personal Communications | 2015 | 2 | 0.261 | 48 | 376/2004 | 4 | 0.701 | 63/85 |

| Distance Education | 2015 | 1 | 1.43 | 40 | 18/263 | 1 | 2.021 | 20/231 |

| Research in Learning Technology | 2015 | 1 | 1.083 | 19 | 20/236 | |||

| Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education | 2016 | 3 | 0.222 | 17 | 8/91 | |||

| Occupational Therapy International | 2016 | 2 | 0.293 | 32 | 4/53 | 4 | 0.780 | 55/65 |

| Journal of Educational Media and Library Sciences | 2016 | 2 | 0.233 | 7 | 9/14 | |||

| Universal Journal of Educational Research | 2018 | 3 | 0.256 | 68 | 70/206 | |||

| Journal of Educators Online | 2019 | 3 | 0.21 | 13 | 4/39 | |||

| Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal | 2019 | 3 | 0.20 | 9 | 3/49 | |||

| Information Resources Management Journal | 2019 | 3 | 0.18 | 37 | 4/25 | |||

| Conference | Place and Year |

|---|---|

| American Society for Engineering Education Conference | San Antonio, United States, 2012 |

| International Conference on Advances in ICT for Emerging Regions (ICTer2012) | Colombo, Sir Lanka, 2012 |

| IADIS International Conference Collaborative Technologies | Prague, Czech Republic, 2013 |

| 4th International Conference on Wireless Communications, Vehicular Technology, Information Theory and Aerospace and Electronics Systems (VITAE) | Aalborg, Denmark, 2014 |

| IEEE/ACM 39th International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering Education and Training Track (ICSE-SEET) | Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017 |

| 2nd International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC) I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC) | Palladam, India, 2018 |

| Sixth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality | Salamanca, Spain, 2018 |

| 4th South-East Europe Design Automation, Computer Engineering, Computer Networks and Social Media Conference (SEEDA-CECNSM) | Piraeus, Greece, 2019 |

| Books | Year |

| The Wiley International handbook of mentoring | 2010 |

| Cases on online tutoring, mentoring, and educational services: Practices and applications | 2010 |

| Pedagogical and Andragogical teaching and learning with information communication technologies | 2011 |

| University | Study Target Group |

|---|---|

| British Columbia University, Canada | Physiotherapy students in rural positions |

| Universidad Federal São Carlos, Brazil | Students of Education, aspiring teachers |

| Drexel University, USA | Psychology Students |

| UCLA, USA | Virtual Undergraduate Students |

| Northern Illinois University, USA | Business Students |

| Aga Khan University, Kenya | Graduate students in Radiology |

| Carnegie Mellon University, USA | Readmitted students and first-year adults |

| Illinois University Urbana-Champaign, USA | Virtual Master’s Students |

| Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Spain | Students of Education |

| LeTourneau University, USA | First year engineering students |

| Colombo University, Sir Lanka | Virtual Undergraduate Students |

| Wisconsin University, USA | Students of Education |

| Pennsylvania University, USA | Business Students |

| Regensburg University, Germany | Female first-year engineering students |

| Maryland University, USA | Master’s students in Biotechnology |

| Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University, Thailand | Computer and Technology Students |

| Boston University, USA | Postdoctoral students in Occupational Therapy |

| Mae Fah Luang University, Phayao University, Chiang Rai Rajabhat University and Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University, Thailand | Computer and technology students |

| Indiana University and Purdue University, USA | Students and teachers of Education |

| Sabah University, Malasya | Students of Psychology and Education programs |

| Te Wānanga O Aotearoa University, New Zealand | Students of Education |

| Anadolu University, Turkey | Students and graduates of Computer and Technology Education |

| University of Boston, Sargent College, USA | Post-Professional Occupational Therapy Students |

| Catholic Fu Jen University, Taiwan | Students of Education |

| Carnegie Mellon University, USA | Software Development Students |

| University X in Japan X (no information) | University students X, no program information |

| Universidad de Manizales, Colombia | Academic Internship Students Marketing Program |

| Te Wānanga O Aotearoa University, New Zealand | Students and teachers of Education |

| Technological University of Visvesvaraya, India | Engineering students |

| Manipal University Jaipur, India | Multi-faculty students with business and entrepreneurial skills |

| University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Wright State University, USA | Business Students |

| American College of Greece, Open University Hellenic, Institute of Political Education of Athens, Greece | Students of Education |

| Niagara University, USA | Students of Education |

| Major Findings | Media | Difference on Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions of mentoring | Article | |

| Conference papers | ||

| Book chapters |

| |

| Purposes of mentoring | Article | |

| Conference papers | ||

| Book chapters | ||

| Goals of mentoring programs | Article | |

| Conference papers | ||

| Book chapters | ||

| Terminology | Article | |

| Conference papers | ||

| Book chapters | ||

| Future of mentoring | Article | |

| Conference papers | ||

| Book chapters |

| Type of Study | Nº Studies | Document |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | 16 | DiRenzo et al., 2010; Venis, 2010; Murphy, 2011; Obura et al., 2011; Green et al., 2012; Gunawardena et al., 2012; De Janasz, and Godshalk, 2013; Khan, and Gogos, 2013; Nuankaew, and Temdee, 2014; Jacobs, et al., 2015; Nuankaew, and Temdee, 2015; Doyle et al., 2016; Tominaga, and Kogo, 2018; Farheen, J., and Dixit, 2018; Doukakis et al., 2019; Briscoe, 2019. |

| Qualitative | 5 | Stewart, and Carpenter, 2009; Rodrigues Reali et al., 2010; Butler et al., 2013; Greindl et al., 2013; Kahraman, and Abdullah, 2016. |

| Mix Methods | 9 | Golubski, 2011, Williams, and Kim, 2011; Risquez, and Sánchez-García, 2012; Drouin et al., 2015; Owen, 2015; ChanLin, 2016; Trainer et al., 2017; Tinoco-Giraldo et al., 2018; Haran, and Jeyaraj, 2019. |

| Additional Research | 3 | Ligadu, and Anthony, 2015; Owen et al., 2018; Singh, and Kumar, 2019. |

| Features Found in the Mentoring Programs | Titles of the Papers |

|---|---|

| It involves personalized attention to mentees | E-mentoring the individual writer within a global creative community (2010). |

| Serve as a place for the exchange of ideas, proposals and experiences | Implementing an industrial mentoring program to enhance student motivation and retention (2012), Using methodological triangulation to examine the effectiveness of a mentoring program for online instructors (2015). |

| Mutually beneficial | Faculty mentors’ perspectives on e-mentoring post-professional occupational therapy doctoral students (2016). |

| Address individual learning needs of the mentees | Determining of compatible different attributes for online mentoring model (2014). |

| Building confidence in handling challenges and problems | E-mentoring alternative paradigm for entrepreneurial aptitude development (2019). |

| Help with advice on professional development and personal growth, as well as networking opportunities. | Utilizing technological ecosystems to support graduate students in their practicum experiences (2018). |

| Support and facilitate the process of construction of learning of various types | The role of e-mentoring in protégés’ learning and satisfaction (2013). |

| Stimulates people’s professional potential based on the transmission of knowledge and learning through experience. | Electronic mentoring: An innovative approach to providing clinical support (2009). |

| Motivate and provoke changes in their values, attitudes and skills | Social impact in personalised virtual professional development pathways (2018). |

| Absence or Incompleteness of Research | |

|---|---|

| Conceptual confusion | Confusion in the definitions, both of e-mentoring and of the roles, functions, and activities of mentors [13]. There are authors who question this clarity and there are those who do not notice this deficiency and argue their proposals amidst the confusion of terms. According to Risquez, and Sánchez-García [49] there is a lack of a precise definition of e-mentoring, which in some cases, causes confusion as it has a different meaning in the higher education field. |

| Disagreements on operational definitions | Lack of precision in the operational definition of e-mentoring in the higher education field, due to the scope of the investigations [51] or because of other particular fields where it occurs [46]. Not having clear concepts and agreed operational definitions at least in each field where e-mentoring takes place can limit the understanding and usefulness of empirical research [48]. |

| Methodological weaknesses | Most of the reports reviewed did not acknowledge the development of specific models for e-mentoring in higher education and there was no clear information on the validation of instruments that assess the factors involved with e-mentoring [20]. |

| Lack of evidence of the characteristics and qualities of an effective e-mentoring. | Tinoco-Giraldo et al. [14] note that extensive work has been done on mentoring over the last two decades. Such research and models focus on the business field and to a lesser extent on the academic field. However, little research addresses the qualities and characteristics of an effective mentor, minimal research investigates the characteristics and qualities of good mentoring [11], and no research in mentoring applied for students in offsite internships [14]. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tinoco-Giraldo, H.; Torrecilla Sánchez, E.M.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. E-Mentoring in Higher Education: A Structured Literature Review and Implications for Future Research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114344

Tinoco-Giraldo H, Torrecilla Sánchez EM, García-Peñalvo FJ. E-Mentoring in Higher Education: A Structured Literature Review and Implications for Future Research. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114344

Chicago/Turabian StyleTinoco-Giraldo, Harold, Eva María Torrecilla Sánchez, and Francisco José García-Peñalvo. 2020. "E-Mentoring in Higher Education: A Structured Literature Review and Implications for Future Research" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114344

APA StyleTinoco-Giraldo, H., Torrecilla Sánchez, E. M., & García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2020). E-Mentoring in Higher Education: A Structured Literature Review and Implications for Future Research. Sustainability, 12(11), 4344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114344