How Should Green Messages Be Framed: Single or Double?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Green Advertising Appeals

2.2. Green Attributes of the Product

2.3. Product Attributes

2.4. Order Effect of Message Presentation

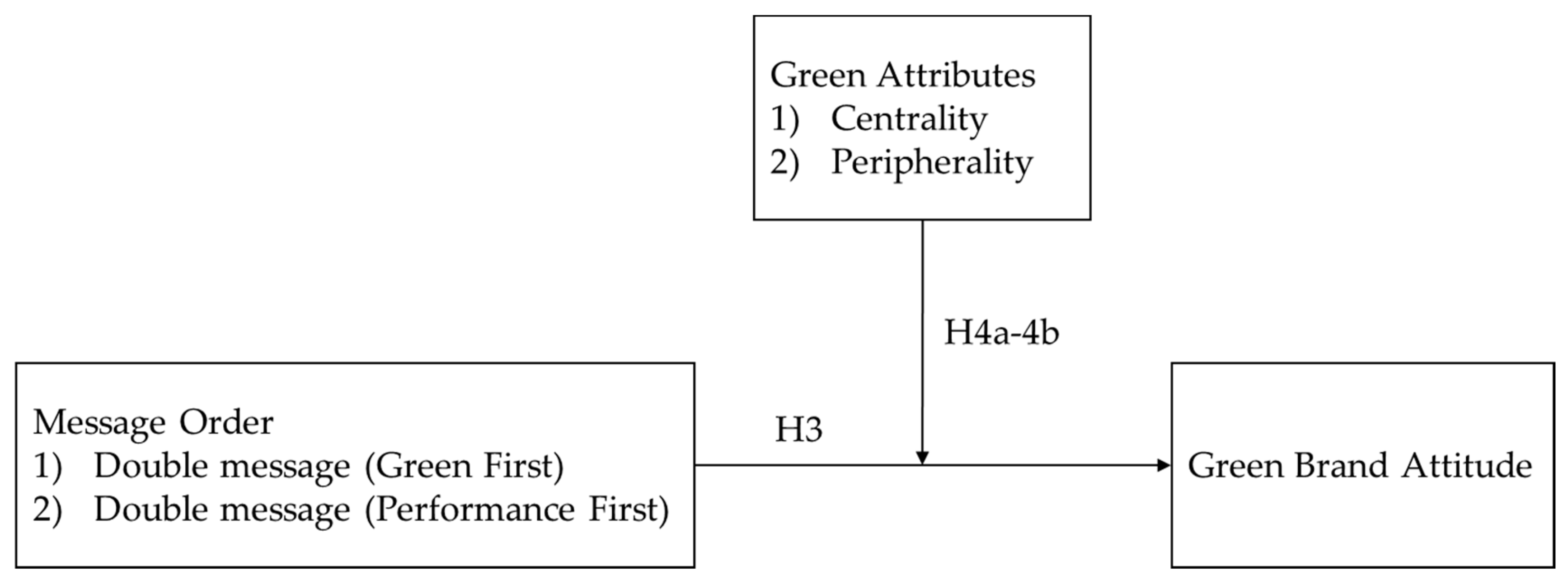

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Single-Message versus a Double-Message Advertisement

3.2. Role of Green Attributes

3.3. Impact of Message Order in a Double-Message Advertisement

4. Study 1

4.1. Experiment Design and Stimuli Advertisement

4.2. Dependent Variables

- (1)

- Denee shampoo is good.

- (2)

- Denee shampoo is pleasing.

- (3)

- Denee shampoo is attractive.

- (4)

- Denee shampoo is of good quality.

4.3. Subjects and Procedure

4.4. Results

4.4.1. Manipulation Check

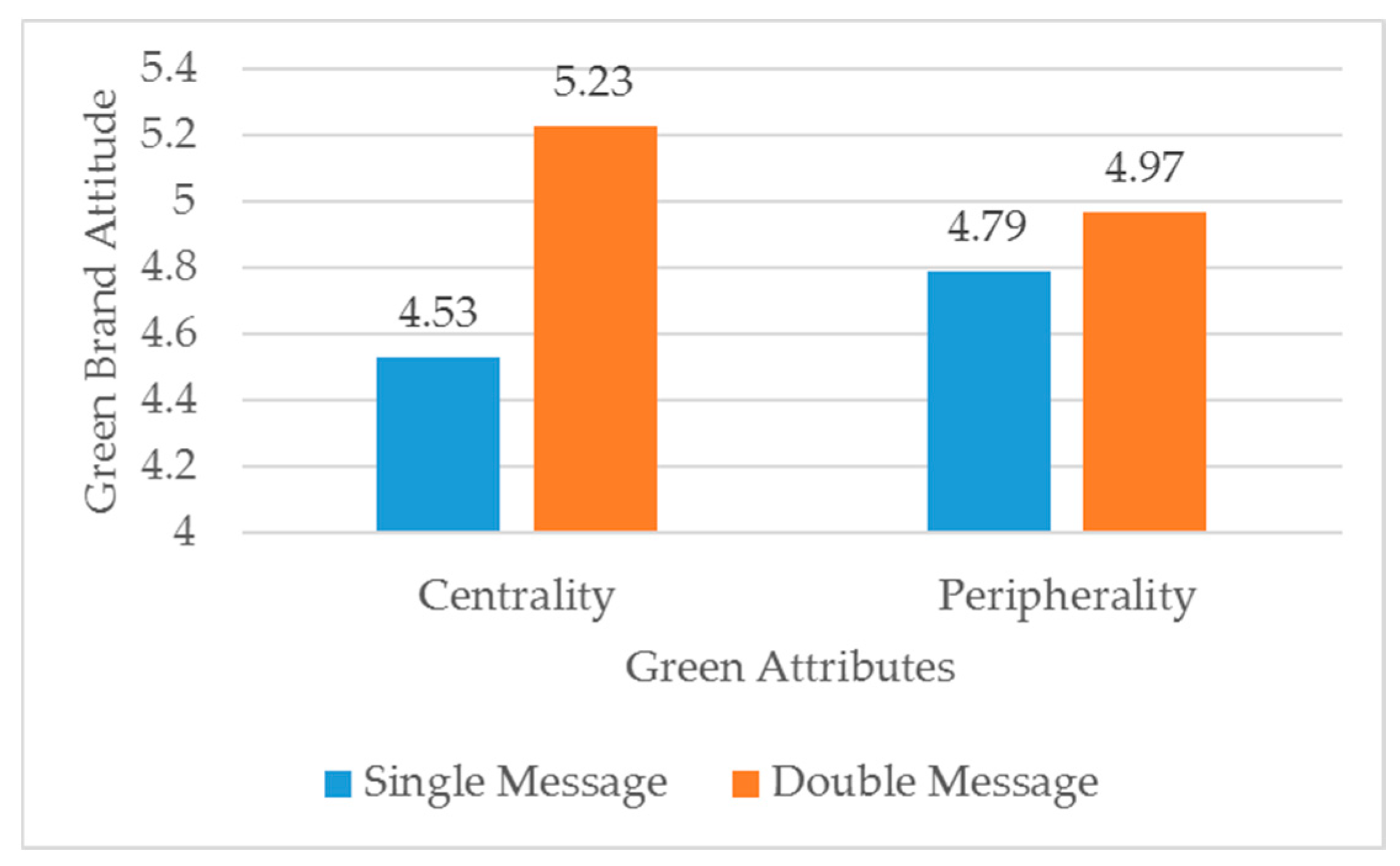

4.4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Study 2

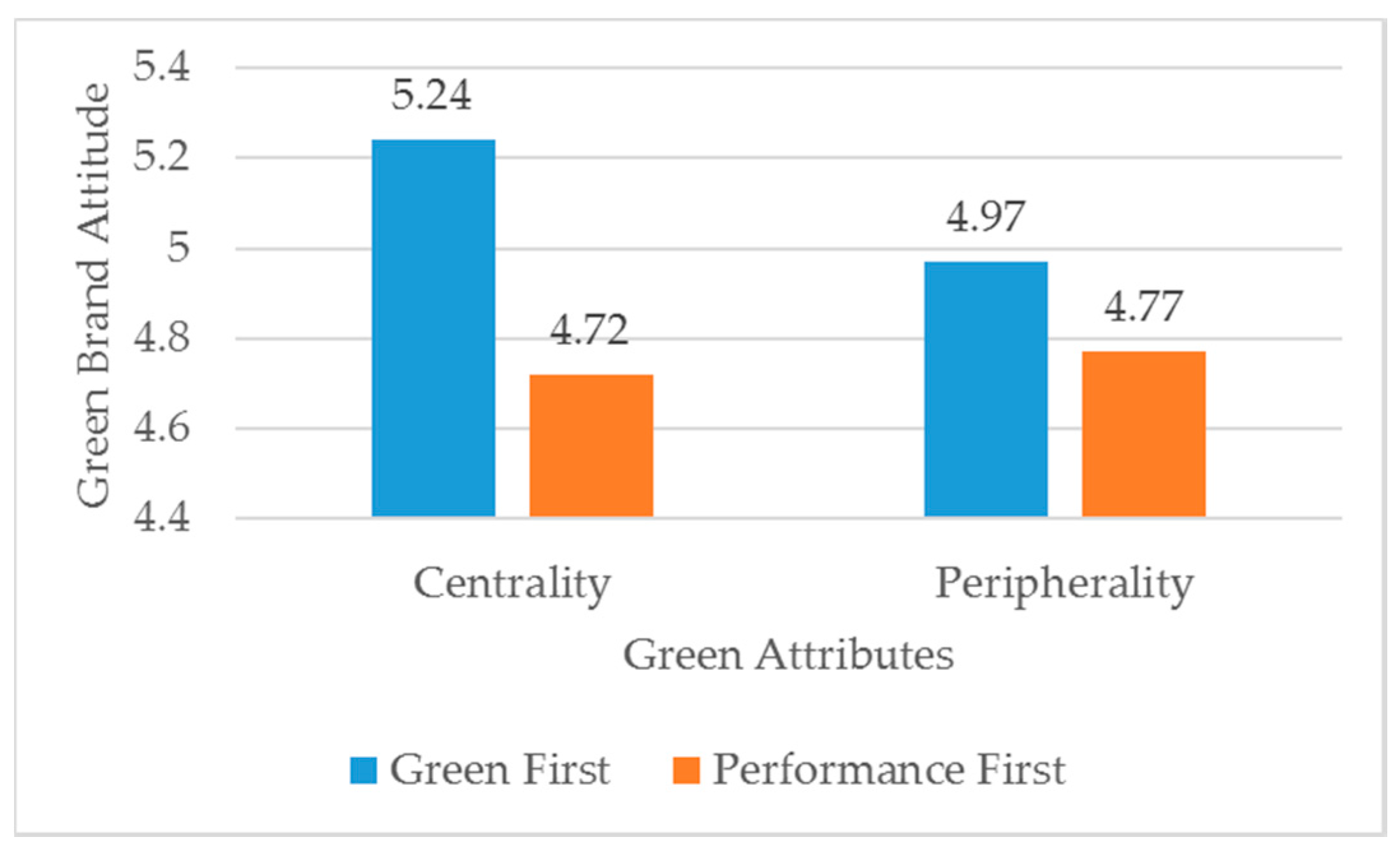

Results

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Managerial Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Approval

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Orsato, R.J. Competitive Environmental Strategies: When Does it Pay to be Green? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolverton, A.; Dimitri, C. Green Marketing: Are Environmental and Social Objectives Compatible with Profit Maximization? Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2010, 25, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselt, J.; Rompay, T.; Haske, L. Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Effects of Internal and External CSR ECO-Labeling. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, E.; Banerjee, B. Anatomy of Green Advertising. Adv. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 494–501. [Google Scholar]

- Durif, F.; Boivin, C.; Julien, C. In Search of a Green Product Definition. Innov. Mark. 2010, 6, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M.A.; Jager, W. Stimulating Diffusion of Green Products. J. Evol. Econ. 2002, 12, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The Sustainability Liability: Potential Negative Effects of Ethicality on Product Preference. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackoy, R.D.; Calantone, R.J.; Droge, C.L. Environmental Marketing: Bridging the Divide Between the Consumption Culture and Environmentalism. In Environmental Marketing: Strategies, Practice, Theory, and Research; Haworth Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1995; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, S.; Oates Caroline, J.; Alevizou Panayiota, J. No Through Road: A Critical Examination of Researcher Assumptions and Approaches to Researching Sustainability. In Review of Marketing Research: Marketing in and for a Sustainable Society; Malhotra, N.K., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2016; Volume 13, pp. 139–168. [Google Scholar]

- Skard, S.; Jørgensen, S.; Pedersen, L.J.T. When is Sustainability a Liability, and When is it an Asset? Quality Inferences for Core and Peripheral Attributes. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Feeling Ambivalent About Going Green. J. Advert. 2011, 40, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, A.D.; Frels, J.K. What Makes it Green? The Role of Centrality of Green Attributes in Evaluations of the Greenness of Products. J. Mark. 2015, 79, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareklas, I.; Carlson, J.R.; Muehling, D.D. The Role of Regulatory Focus and Self-View in “Green” Advertising Message Framing. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.-C.; Chang, H.-H.; Chang, A. Consumer Personality and Green Buying Intention: The Mediate Role of Consumer Ethical Beliefs. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, G.E.; Gorlin, M.; Dhar, R. When Going Green Backfires: How Firm Intentions Shape the Evaluation of Socially Beneficial Product Enhancements. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Simpson, B. When Do (and Don’t) Normative Appeals Influence Sustainable Consumer Behaviors? J. Mark. 2013, 77, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as Mother of ‘Green’ Inventions: Institutional Pressures and Environmental Innovations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. The Determinants of Green Product Development Performance: Green Dynamic Capabilities, Green Transformational Leadership, and Green Creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.L. Perspective: The Green Innovation Value Chain: A Tool for Evaluating the Diffusion Prospects of Green Products. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.; Peloza, J. Finding the Right Shade of Green: The Effect of Advertising Appeal Type on Environmentally Friendly Consumption. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M.; Woolley, M. Green Marketing Messages and Consumers’ Purchase Intentions: Promoting Personal versus Environmental Benefits. J. Mark. Commun. 2014, 20, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A. The Skeptical Green Consumer Revisited: Testing the Relationship Between Green Consumerism and Skepticism Toward Advertising. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A.; Schmuck, D. Consumers’ Green Involvement and The Persuasive Effects of Emotional versus Functional Ads. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segev, S.; Fernandes, J.; Hong, C. Is Your Product Really Green? A Content Analysis to Reassess Green Advertising. J. Advert. 2016, 45, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’souza, C.; Taghian, M. Green Advertising Effects on Attitude and Choice of Advertising Themes. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2005, 17, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Leonidou, L.C. Research into Environmental Marketing/Management: A Bibliographic Analysis. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 68–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Marketing: An Integrative Framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.; Liu, M.T.; Liu, Y. Effects of Functional Green Advertising on Self and Others. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.Y.; Kim, Y.-K. Doing Good Better: Impure Altruism in Green Apparel Advertising. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Luximon, Y. Design for Sustainability: The Effect of Lettering Case on Environmental Concern from a Green Advertising Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinkhan, G.M.; Carlson, L. Green Advertising and the Reluctant Consumer. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Gulas, C.S.; Iyer, E. Shades of Green: A Multidimensional Analysis of Environmental Advertising. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.; Grove, S.J.; Kangun, N. A Content Analysis of Environmental Advertising Claims: A Matrix Method Approach. J. Advert. 1993, 22, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, D.; Matthes, J.; Naderer, B. Misleading Consumers With Green Advertising? An Affect–Reason–Involvement Account of Greenwashing Effects in Environmental Advertising. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Cao, C.; Huang, S. The Influence of Greenwashing Perception on Green Purchasing Intentions: The Mediating Role of Green Word-of-Mouth and Moderating Role of Green Concern. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and Green Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Green Skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, A.R., III; Close, A.G. It Ain’t Easy Being Green: Macro, Meso, and Micro Green Advertising Agendas. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Kumar, M. “Yes, But This Other One Looks Better/Works Better”: How do Consumers Respond to Trade-Offs Between Sustainability and Other Valued Attributes? J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L.; Rosenthal, S. Signaling the Green Sell: The Influence of Eco-Label Source, Argument Specificity, and Product Involvement on Consumer Trust. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.M.J.; Chiu, A.S.F.; Seva, R. A Proposed Framework on the Affective Design of Eco-Product Labels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, C.N.; Keramitsoglou, K.M.; Kalogeras, N.; Tsagkaraki, M.I.; Kalatzi, I.; Tsagarakis, K.P. Can the “Euro-Leaf” Logo Affect Consumers’ Willingness-to-Buy and Willingness-to-Pay for Organic Food and Attract Consumers’ Preferences? An Empirical Study in Greece. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancer, E.; McShane, L.; Noseworthy, T.J. Isolated Environmental Cues and Product Efficacy Penalties: The Color Green and Eco-Labels. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phau, I.; Ong, D. An Investigation of the Effects of Environmental Claims in Promotional Messages for Clothing Brands. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2007, 25, 772–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, B.; Grimes, A. How Claim Specificity can Improve Claim Credibility in Green Advertising: Measures that can Boost Outcomes from Environmental Product Claims. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoro Rios, F.J.; Luque Martinez, T.; Fuentes Moreno, F.; Cañadas Soriano, P. Improving Attitudes Toward Brands With Environmental Associations: An Experimental Approach. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, E.M.; Rifon, N.J.; Lee, E.M.; Reece, B.B. Consumer Receptivity to Green Ads: A Test of Green Claim Types and the Role of Individual Consumer Characteristics for Green Ad Response. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhwerk, M.E.; Lefkoff-Hagius, R. Green or Non-Green? Does Type of Appeal Matter When Advertising a Green Product? J. Advert. 1995, 24, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronrod, A.; Grinstein, A.; Wathieu, L. Go Green! Should Environmental Messages be so Assertive? J. Mark. 2012, 76, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza, V.; D’Souza, C.; Barrutia, J.M.; Echebarria, C. Environmental Threat Appeals in Green Advertising: The Role of Fear Arousal and Coping Efficacy. Int. J. Advert. 2014, 33, 741–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; White, K.; Shang, J. Good and Guilt-Free: The Role of Self-Accountability in Influencing Preferences for Products with Ethical Attributes. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, H.; Duval, K.; Grohmann, B. Will You Purchase Environmentally Friendly Products? Using Prediction Requests to Increase Choice of Sustainable Products. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-c.A. Double Standard: The Role of Environmental Consciousness in Green Product Usage. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.; Robinson, S.; Poor, M. The Efficacy of Green Package Cues for Mainstream versus Niche Brands: How Mainstream Green Brands can Suffer at The Shelf. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.L. It’s not Easy Being Green: The Effects of Attribute Tradeoffs on Green Product Preference and Choice. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arceneaux, K. Cognitive Biases and the Strength of Political Arguments. Am. J. Political Sci. 2012, 56, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Word of Mouth for Movies: Its Dynamics and Impact on Box Office Revenue. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizerski, R.W. An Attribution Explanation of the Disproportionate Influence of Unfavorable Information. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.Y.; Kim, Y.-K. A Human-Centered Approach to Green Apparel Advertising: Decision Tree Predictive Modeling of Consumer Choice. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloman, S.A.; Love, B.C.; Ahn, W.K. Feature Centrality and Conceptual Coherence. Cogn. Sci. 1998, 22, 189–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, J.A.; Passanisi, A.; Jönsson, M.L. The Modifier Effect and Property Mutability. J. Mem. Lang. 2011, 64, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, R.M.; Einhorn, H.J. Order Effects in Belief Updating: The Belief-Adjustment Model. Cogn. Psychol. 1992, 24, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubbs, R.M.; Gaeth, G.J.; Levin, I.P.; Van Osdol, L.A. Order Effects in Belief Updating with Consistent and Inconsistent Evidence. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 1993, 6, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotman, K.T.; Wright, A. Order Effects and Recency: Where do We Go from Here? Account. Financ. 2000, 40, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Forming Impressions of Personality. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1946, 41, 258–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, K.E.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Dimensions of Consumer Attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Brower, J.; Chitturi, R. Product Choice and the Importance of Aesthetic Design Given the Emotion-Laden Trade-Off between Sustainability and Functional Performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.W.; Chan, R.Y.K. Why and When do Consumers Perform Green Behaviors? An Examination of Regulatory Focus and Ethical Ideology. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, A.R.; Wilkie, J.E.B.; Ma, J.; Isaac, M.S.; Gal, D. Is Eco-Friendly Unmanly? The Green-Feminine Stereotype and its Effect on Sustainable Consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, S.; Sheehan, K. The Role of Guilt in Influencing Sustainable Pro-Environmental Behaviors Among Shoppers: Differences in Response by Gender to Messaging About England’s Plastic-Bag Levy. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Polonsky, M.J.; Vocino, A.; Siwar, C. Measuring Consumer Understanding and Perception of Eco-Labelling: Item Selection and Scale Validation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.K.; Kushwaha, G.S. Eco-Labels: A Tool for Green Marketing or Just a Blind Mirror for Consumers. Electron. Green J. 2019, 1, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taljaard, H.; Sonnenberg, N.C.; Jacobs, B.M. Factors Motivating Male Consumers’ Eco-Friendly Apparel Acquisition in the South African Emerging Market. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, A.; Kellaris, J. How Logo Colors Influence Shoppers’ Judgments of Retailer Ethicality: The Mediating Role of Perceived Eco-Friendliness. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 146, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, A.C.-H.; Wu, H.-H. How Should Green Messages Be Framed: Single or Double? Sustainability 2020, 12, 4257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104257

Chen AC-H, Wu H-H. How Should Green Messages Be Framed: Single or Double? Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104257

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Arthur Cheng-Hsui, and Hsiu-Hui Wu. 2020. "How Should Green Messages Be Framed: Single or Double?" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104257

APA StyleChen, A. C.-H., & Wu, H.-H. (2020). How Should Green Messages Be Framed: Single or Double? Sustainability, 12(10), 4257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104257