The Future of Yak Farming from the Perspective of Yak Herders and Livestock Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

- -

- Respondent’s perceived level of concern about factors related to yak farming challenges.

- -

- Respondent’s future plans with developing yak herd size in the next 10 years, their wish for their children to continue yak farming, and their opinion on the number of yak farming families in the next 10 years.

2.3. Characteristics of the Herders

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

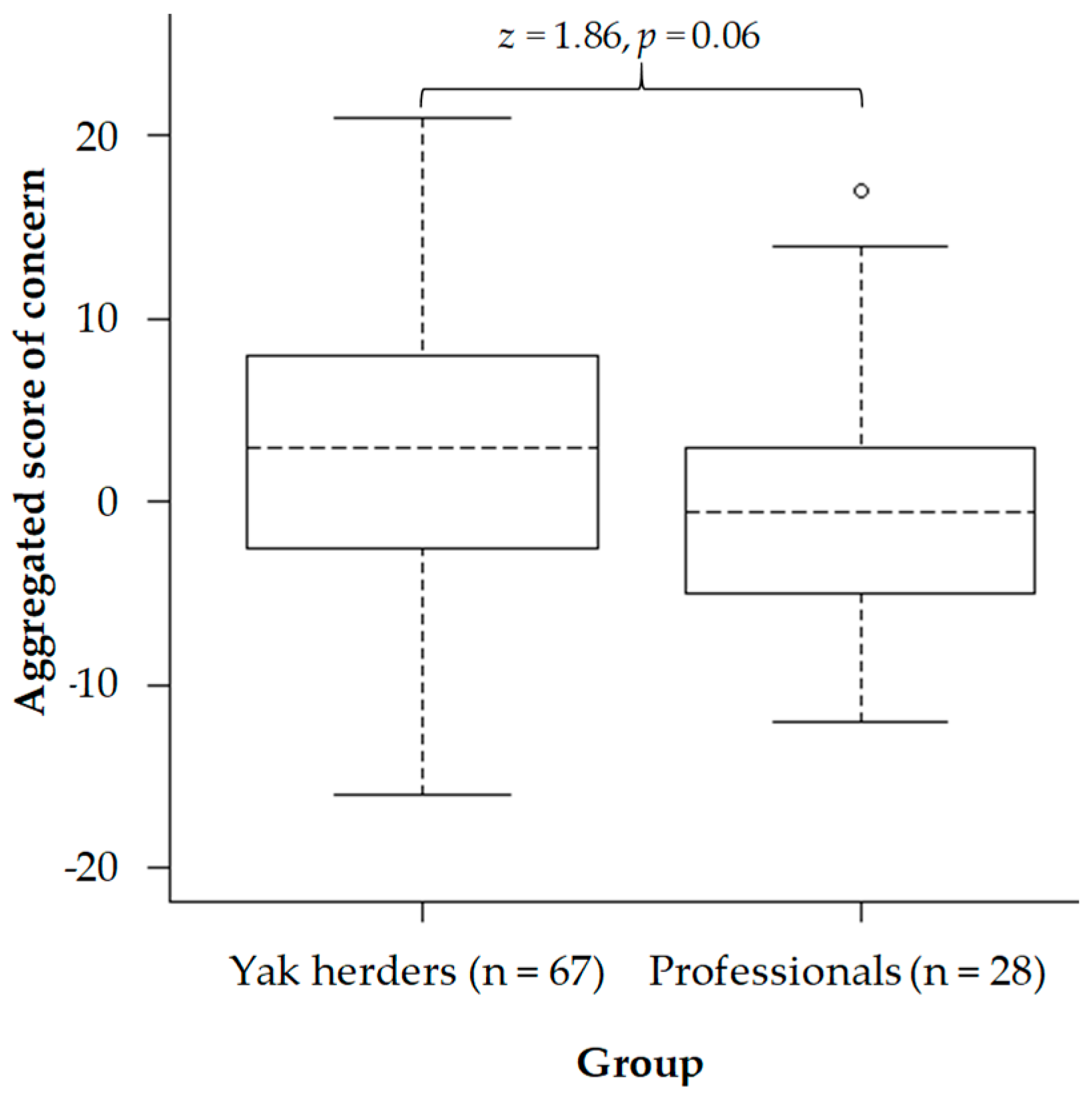

3.1. Concern Factors Related to Yak Farming

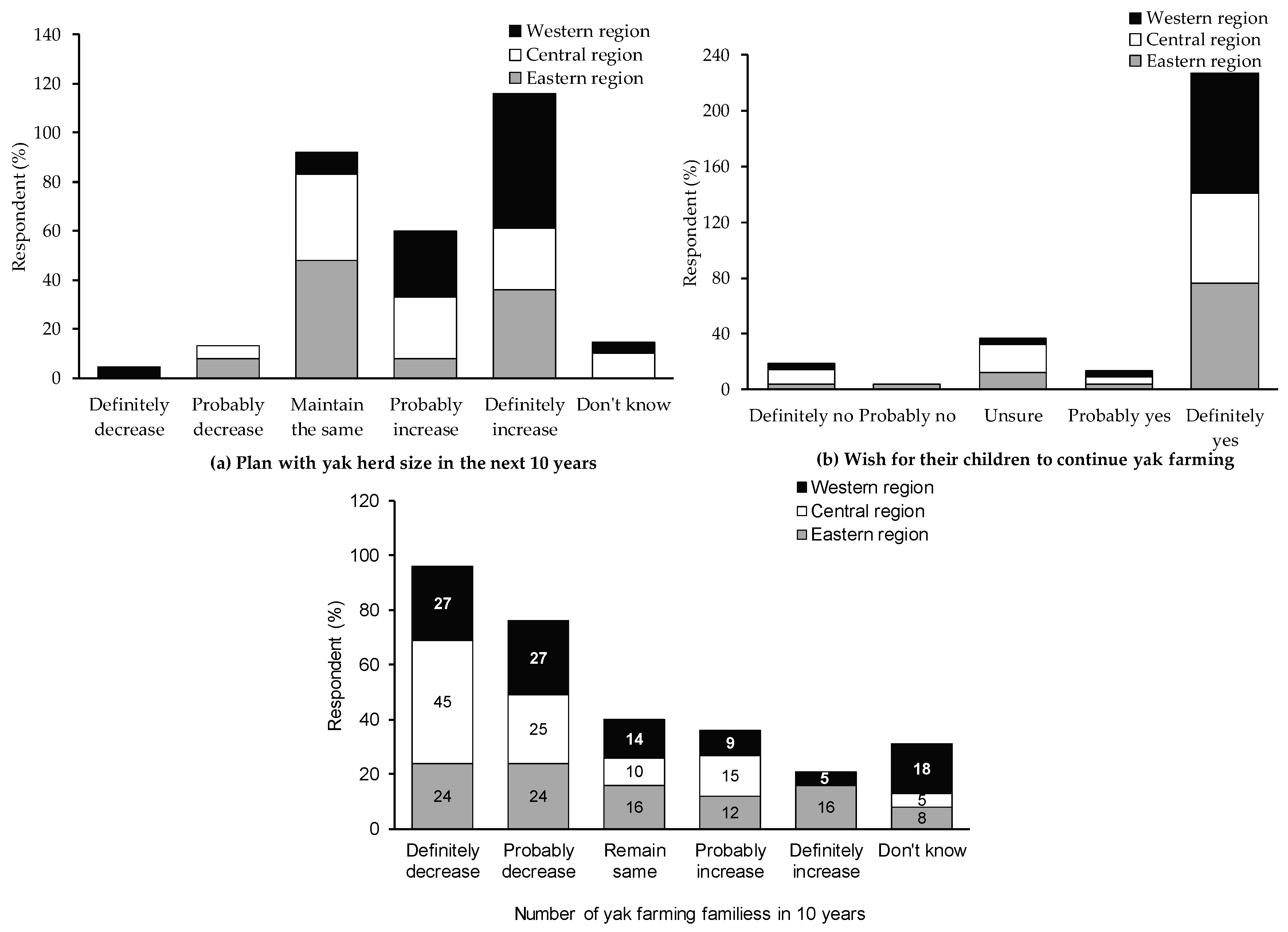

3.2. Herders’ Future Plan with Herd Size

3.3. Herders’ Wish for their Children to Continue Yak Farming

3.4. Number of Yak Farming Families in 10 Years

3.5. Association between the Herders’ Plans and Decisions on Yak Farming

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Aspects | Level of Perceived Concern (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at All | To Small Extent | To Moderate Extent | To Large Extent | Don’t Know | |

| Forage availability in winter rangeland | |||||

| Yak herders | 11.9 | 13.4 | 25.4 | 47.8 | 1.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 10.7 | 25 | 28.6 | 28.6 | 7.1 |

| Forage availability in summer rangeland | |||||

| Yak herders | 10.5 | 17.9 | 23.9 | 47.8 | 0 |

| Livestock professionals | 0 | 25 | 28.6 | 64.4 | 0 |

| Water availability | |||||

| Yak herders | 53.7 | 10.4 | 19.4 | 14.9 | 1.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 14.3 | 3.6 | 46.4 | 21.4 | 14.3 |

| Quality breeding bull availability | |||||

| Yak herders | 59.7 | 13.4 | 17.9 | 9 | 0 |

| Livestock professionals | 7.1 | 25 | 25 | 11 | 3.6 |

| Conception rate of yak cow | |||||

| Yak herders | 61.2 | 11.9 | 17.9 | 1.5 | 7.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 17.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 | 14.3 | 10.7 |

| Milk yield of yak cow | |||||

| Yak herders | 34.3 | 11.9 | 26.9 | 25.4 | 1.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 21.4 | 28.6 | 32.1 | 14.3 | 3.6 |

| Body size of adult yak | |||||

| Yak herders | 38.8 | 23.9 | 25.4 | 10.4 | 1.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 21.4 | 35.7 | 21.4 | 3.6 | 17.9 |

| Prevalence of diseases and parasites | |||||

| Yak herders | 32.8 | 23.9 | 14.9 | 23.9 | 4.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 7.1 | 39.3 | 32.1 | 21.4 | 0 |

| Access to veterinary and extension services | |||||

| Yak herders | 46.3 | 29.9 | 13.4 | 9 | 1.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 17.9 | 14.3 | 25 | 42.9 | 0 |

| Predation on yaks | |||||

| Yak herders | 9 | 10.5 | 19.4 | 58.2 | 3.0 |

| Livestock professionals | 0 | 14.3 | 7.1 | 71.4 | 7.1 |

| Market for selling yak products | |||||

| Yak herders | 79.1 | 13.4 | 6 | 0 | 1.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 17.9 | 14.3 | 32.1 | 28.6 | 7.1 |

| Labour availability to herd yaks | |||||

| Yak herders | 49.3 | 22.4 | 17.9 | 9 | 1.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 3.6 | 28.6 | 25 | 39.3 | 3.6 |

| Successor (youth) to yak farming | |||||

| Yak herders | 22.9 | 17.9 | 26.9 | 28.4 | 4.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 10.7 | 14.3 | 21.4 | 39.3 | 14.3 |

| Yak population in the community | |||||

| Yak herders | 44.8 | 19.4 | 20.9 | 14.9 | 0 |

| Livestock professionals | 17.9 | 42.9 | 17.9 | 21.4 | 0 |

| Number of yak farming families | |||||

| Yak herders | 49.3 | 17.9 | 13.4 | 19.4 | 0 |

| Livestock professionals | 21.4 | 17.9 | 35.7 | 21.4 | 3.6 |

| Training to improve yak management practices | |||||

| Yak herders | 52.2 | 29.9 | 6 | 7.5 | 4.5 |

| Livestock professionals | 7.1 | 14.3 | 46.4 | 28.6 | 3.6 |

References

- Allen, V.G.; Batello, C.; Berretta, E.J.; Hodgson, J.; Kothmann, M.; Li, X.; McIvor, J.; Milne, J.; Morris, C.; Peeters, A.; et al. An international terminology for grazing lands and grazing animals. Grass Forage Sci. 2011, 66, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyamtsho, P. Economy of yak herders. J. Bhutan Stud. 2000, 2, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Suntikul, W.; Dorji, U. Tourism development: The challenges of achieving sustainable livelihoods in Bhutan’s remote reaches. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Shrestha, L.; Bisht, N.; Wu, N.; Ismail, M.; Dorji, T.; Dangol, G.; Long, R. Ethnic and cultural diversity amongst yak herding communities in the Asian highlands. Sustainability 2020, 12, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, K.; Wangdi, J. Mountain pastoralism in transition: Consequences of legalizing Cordyceps collection on yak farming practices in Bhutan. Pastoralism 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derville, M.; Bonnemaire, J. Marginalisation of Yak Herders in Bhutan: Can Public Policy Generate New Stabilities that can Support the Transformation of Their Skills and Organisations? And Bonds to Territories: A Case Study in France and Brazil; ISDA: Montpellier, France, 2010; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Dorji, N.; Derks, M.; Dorji, P.; Groot Koerkamp, P.W.G.; Bokkers, E.A.M. Resilience of yak farming in Bhutan. In 70th Annual Meeting of the European Federation of Animal Science; Book of abstracts, 25; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands; Ghent, Belgium, 2019; p. 426. [Google Scholar]

- Wangchuk, K.; Wangdi, J. Signs of climate warming through the eyes of yak herders in northern Bhutan. Mt. Res. Dev. 2018, 38, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangdi, J. The future of yak farming in Bhutan: Policy measures government should adopt. Rangel. J. 2016, 38, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuntsho, K.; Dorji, T. Yak herding in Bhutan: Policy and practice. In Transboundary Challenges and Opportunities for Yak Raising in a Changing Hindu Kush Himalayan Region; Wu, N., Yi, S., Joshi, S., Bisht, N., Eds.; International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016; pp. 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Corner-Thomas, R.A.; Kenyon, P.R.; Morris, S.T.; Ridler, A.L.; Hickson, R.E.; Greer, A.W.; Logan, C.M.; Blair, H.T. Influence of demographic factors on the use of farm management tools by New Zealand farmers. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 58, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeni, L.; Moeletsi, M.; Thavhana, M.; Randela, M.; Mokoena, L. Barriers affecting sustainable agricultural productivity of smallholder farmers in the eastern free state of South Africa. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, A.; Raubenheimer, D.; McGreevy, P. What we know about the public’s level of concern for farm animal welfare in food production in developed countries. Animals 2016, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DoL. Livestock Statistics 2007; Livestock, D.O., Ed.; Ministry of Agriculture and Forests: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2007; p. 131.

- Gliem, J.A.; Gliem, R.R. Calculating, interpreting, and reporting Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for Likert-type scales. In Midwest Research to Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education; The Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, F.; Christley, R.; Campe, A. Invited review: Examining farmers’ personalities and attitudes as possible risk factors for dairy cattle health, welfare, productivity, and farm management: A systematic scoping review. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 3805–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willock, J.; Deary, I.J.; McGregor, M.M.; Sutherland, A.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Morgan, O.; Dent, B.; Grieve, R.; Gibson, G.; Austin, E.; et al. Farmers’ attitudes, objectives, behaviors, and personality traits: The Edinburgh study of decision making on farms. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 5–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, J.I. Multicollinearity and regression analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 949, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, M. Goodness of Fit Tests for Logistic Regression Models. 2019, p. 10. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/generalhoslem/generalhoslem.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2020).

- Tuszynski, J. Package ‘caTools’; 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/caTools/caTools.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Hu, B.; Shao, J.; Palta, M. Pseudo-R2 in logistic regression model. Stat. Sin. 2006, 16, 847–860. [Google Scholar]

- Cureton, E.E. Rank-biserial correlation. Psychometrika 1956, 21, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.-Y.J.; Lee, K.L.; Ingersoll, G.M. An introduction to logistic regression analysis and reporting. J. Educ. Res. 2002, 96, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, L.D. Basic concepts of statistical analysis for surgical research. J. Surg. Res. 2005, 128, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukchin, S.; Kerret, D. Food for hope: The role of personal resources in farmers’ adoption of green technology. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.R.; Burton, R.; Buchanan, O.; Birnie, R. Limited adoption of biomass energy crops: The role of farmers’ socio-cultural identity in influencing practice. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 45, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Jones, G. Modelling farmer decision-making: Concepts, progress and challenges. Anim. Sci. 2006, 82, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J. How to Interpret Regression Models that Have Significant Variables but a Low R-Squared. Available online: https://statisticsbyjim.com/regression/interpret-coefficients-p-values-regression/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- McFadden, D. Quantitative methods for analysing travel behaviour of individuals: Some Recent developments. In Behavioural Travel Modelling; Hensher, D.A., Stopher, P.R., Eds.; Croom Helm.: London, UK, 1979; pp. 279–318. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, K.R.; Sitaula, B.K.; Bajracharya, R.M.; Raut, N.; Bhusal, P.; Sengel, M. Vulnerability of pastoralism: A case study from the high mountains of Nepal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorway, R.; Dorji, G.; Bradley, J.; Ramesh, B.M.; Isaac, S.; Blanchard, J. The drayang girls of Thimphu: Sexual network formation, transactional sex and emerging modernities in Bhutan. Cult. Health Sex. 2011, 13 (Suppl. 2), S293–S308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walcott, S. Urbanization in Bhutan. Geogr. Rev. 2009, 99, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S.; Maraseni, T.N.; Cockfield, G.J. Sustainability of transhumance grazing systems under socio-economic threats in Langtang, Nepal. J. Mt. Sci. 2014, 11, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteros-Rozas, E.; Ontillera-Sánchez, R.; Sanosa, P.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Reyes-García, V.; González, J.A. Traditional ecological knowledge among transhumant pastoralists in Mediterranean Spain. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurt, C.; Häberli, I.; Rossier, R. Transhumance farming in Swiss mountains: Adaptation to a changing environment. Mt. Res. Dev. 2015, 35, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteros-Rozas, E.; Martín-López, B.; López, C.A.; Palomo, I.; González, J.A. Envisioning the future of transhumant pastoralism through participatory scenario planning: A case study in Spain. Rangel. J. 2013, 35, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, V. Pastoralists of Himalayas. J. Hum. Ecol. 2011, 33, 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernués, A.; Ruiz, R.; Olaizola, A.; Villalba, D.; Casasús, I. Sustainability of pasture-based livestock farming systems in the European Mediterranean context: Synergies and trade-offs. Livest. Sci. 2011, 139, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, D. Steps towards Sustainable Harvest of Yartsa Gunbu (Caterpillar Fungus, Ophiocordyceps sinensis). In Proceedings of the 7th International Medicinal Mushroom Conference, Beijing, China, 25–29 August 2013; pp. 635–644. [Google Scholar]

- Hopping, K.A.; Chignell, S.M.; Lambin, E.F. The demise of caterpillar fungus in the Himalayan region due to climate change and overharvesting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11489–11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, M.A.; Din, J.U.; Buzdar, H. Chapter 14–Livestock husbandry and snow leopard conservation. Subchapter–The ecosystem health program: A tool to promote the coexistence of livestock owners and snow leopards. In Snow Leopards; McCarthy, T., Mallon, D., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, M.B.; Fazzio, I.; Irons, W.G.; Bowles, S.; Bell, A.V.; Hertz, T.; Hazzah, L. Revisiting an old question: Pastoralism and wealth inequality. Curr. Anthropol. 2010, 51, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherchan, R.; Bhandari, A. Status and trends of human-wildlife conflict: A case study of Lelep and Yamphudin region, Kanchenjunga Conservation Area, Taplejung, Nepal. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 5, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, M.W.; Bårdsen, B.-J. Environmental stochasticity and long-term livestock viability—herd-accumulation as a risk reducing strategy. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPeak, J. Individual and collective rationality in pastoral production: Evidence from Northern Kenya. Hum. Ecol. 2005, 33, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondersteijn, C.J.M.; Giesen, G.W.J.; Huirne, R.B.M. Identification of farmer characteristics and farm strategies explaining changes in environmental management and environmental and economic performance of dairy farms. Agric. Syst. 2003, 78, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, J.I.; Eastwood, C.R.; Garcia, S.C.; Lyons, N.A. Dairy farmers with larger herd sizes adopt more precision dairy technologies. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 5466–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.L. Rural out-migration and smallholder agriculture in the southern Ecuadorian Andes. Popul. Environ. 2009, 30, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Block | Altitude (masl) | Coordinates | Source of Income | Yak Dairy Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | Merag | 3215 | 27°17′49.20″ N 91°50′6.00″ E | Yak, cattle and cattle–yak hybrids, sheep, medicinal plants | Butter, cheese (fermented and fresh) |

| Central | Saephu | 3500 | 27°29′10.14″ N 89°53′56.94″ E | Yak, cattle and cattle–yak hybrids, cordyceps, medicinal plants, vegetables (potatoes, cabbages) | Butter, cheese (dried and fresh) |

| West | Laya | 3800 | 28°04′00.00″ N 89°41′00.00″ E | Yak, horse, tourism, cordyceps, medicinal plants, agriculture (buckwheat, mustard) | Butter, cheese (dried and fresh) |

| Variables | Description of Topics Addressed |

|---|---|

| Independent | |

| Yak farming region | East, central, west. |

| Respondent’s sex | Male, female. |

| Respondent’s age | Years |

| Respondent’s education | Illiterate (cannot read and write), literate |

| Number of yak herders | One, more than one person involved in yak farming |

| Size of yak herd owned | Total number of yaks owned by the herder. |

| Preferred source of income | Yak farming, other (cordyceps collection, tourism, cattle and cattle–yak hybrid farming, small business) |

| Dependent | |

| Concern factors related to yak farming 1 | Are you concerned about [a concern factor] in relation to yak farming practices? 4-point Likert-scale: 1 = not at all concerned, 2 = to a small extent concerned, 3 = to a moderate extent concerned, 4 = to a large extent concerned, 0 = I don’t know. Concern factors questioned are: yak population size in the community, summer forage availability, winter forage availability, water availability, access to a high-quality breeding bull, conception rate of yak cows, yak body size, milk yield, prevalence of diseases and parasites, access to veterinary and extension services, predation, market situation, labour availability, successor to continue yak farming, number of yak farming families, and training availability to improve yak farming. |

| Future plan with herd size | What is your plan with respect to the yak herd size in the next 10 years? Binary variable: 0 = definitely decrease, probably decrease, or maintain the same, 1 = probably increase, or definitely increase. |

| Wish for their children to continue yak farming | Do you wish your children to continue yak farming? Binary variable: 0 = definitely no, probably no, or unsure, 1 = probably yes or definitely yes. |

| Future trend of yak farming families | How do you see the number of yak farming families developing in the next 10 years? Binary variable: 0 = definitely decrease or probably decrease, 1 = or remain same, probably increase, or definitely increase. |

| Variable | Coef. | SE | t Value | p > |t| | Odds Ratio | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region east (intercept) | 2.34 | 5.51 | 0.42 | 0.67 | 10.39 | 1.36 |

| Region central | −2.29 | 2.46 | −0.93 | 0.35 | 0.10 | |

| Region west | −2.97 | 2.63 | −1.13 | 0.26 | 0.05 | |

| Sex female | −0.07 | 2.35 | −0.03 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.47 |

| Age | −0.04 | 0.09 | −0.49 | 0.62 | 0.96 | 1.69 |

| Education literate | −1.56 | 2.94 | −0.53 | 0.60 | 0.21 | 1.46 |

| Size of the herd owned | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.13 | 0.04* | 1.07 | 1.13 |

| More than one herder involved in herding | 0.61 | 2.15 | 9.28 | 0.78 | 1.84 | 1.20 |

| Prefer source of income (others) | −0.11 | 2.10 | −0.05 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 1.10 |

| Plan | Reasons | Respondents (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Increase herd size (n = 39) 1 | Yak has multiple functions and generates therefore more income | 27 |

| Yak farming is a traditional way of life | 6 | |

| Other (measure to cope with high mortality due to predation, if more rangeland is available, social status) | 8 | |

| Maintain same herd size (n = 21) 1 | Selling yak products meet the daily household requirements | 12 |

| Family labour is sufficient present | 10 | |

| Rangeland owned by family is sufficient for current herd size | 7 | |

| No successor but yak farming is the main livelihood | 5 | |

| Yak farming is a traditional way of life | 1 | |

| Decrease herd size (n = 4) | No successor | 3 |

| Forage shortage | 1 | |

| Not sure (n = 3) | 3 |

| Variable | Coef. | SE | z Value | p > |z| | Marginal Effects | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | SE | ||||||

| Region east (intercept) | 1.40 | 1.45 | 0.97 | 0.33 | 1.44 | ||

| Region central | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.63 | 0.08 | 0.16 | |

| Region west | 2.27 | 0.87 | 2.61 | 0.01* | 0.43 | 0.13 | |

| Sex female | −0.80 | 0.72 | −1.11 | 0.27 | −0.15 | 0.13 | 1.53 |

| Age | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.20 | 0.23 | −0.01 | 0 | 1.44 |

| Education literate | −0.29 | 0.77 | −0.37 | 0.71 | −0.05 | 0.15 | 1.21 |

| Size of the herd owned | 0 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.32 | 1.11 |

| More than one herder involved in herding | 0.05 | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 1.18 |

| Prefer source of income (others) | −0.45 | 0.62 | −0.71 | 0.48 | −0.09 | 0.13 | 1.10 |

| Opinions | Reasons | Respondents (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Wish for the children to continue yak farming in the future | ||

| Yes (n = 55) 1 | Yak farming is a reliable source of income | 38 |

| Yak farming is a traditional way of life | 17 | |

| Children are interested to continue yak farming | 1 | |

| Depends on children as it is a challenging occupation | 3 | |

| Not sure (n = 8) | Depends on children as it is a challenging occupation | 8 |

| No (n = 4) | Forage shortage | 1 |

| Yak farming is a challenging occupation | 3 | |

| Number of yak farming families | ||

| Increase (n = 13) 1 | Yak herd division among family members | 7 |

| Yak farming is a reliable source of income | 4 | |

| Government support to yak farming | 3 | |

| Children are interest to continue yak farming | 1 | |

| Remain same (n = 8) | Yak farming is a traditional life style | 4 |

| Rangeland owned by a family is sufficient | 3 | |

| Yak farming is a reliable source of income | 1 | |

| Decrease (n = 39) 1 | Easy lifestyles at towns (challenging occupation) | 37 |

| Others (forage shortage, yak mortality, alternate income) | 7 | |

| Don’t know (n = 7) | 7 | |

| Variable | Coef. | SE | z Value | p > |z| | Marginal Effects | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | SE | ||||||

| Region east (intercept) | −3.54 | 2.21 | −1.60 | 0.11 | 1.60 | ||

| Region central | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0 | 0.13 | |

| Region west | 2.44 | 1.19 | 2.04 | 0.04 * | 0.25 | 0.11 | |

| Sex female | −0.42 | 0.84 | −0.50 | 0.62 | −0.05 | 0.11 | 1.45 |

| Age | 0.08 | 0.04 | 2.13 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0 | 1.53 |

| Education literate | −0.17 | 0.90 | −0.19 | 0.85 | −0.02 | 0.12 | 1.31 |

| Size of the herd owned | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.34 | 0.18 | 0 | 0 | 1.22 |

| More than one herder involved in herding | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.40 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 1.22 |

| Prefer source of income (others) | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0 | 0.10 | 1.28 |

| Variable | Coef. | SE | z Value | p > |z| | Marginal Effects | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | SE | ||||||

| Region east (intercept) | −0.50 | 1.33 | −0.38 | 0.71 | 1.54 | ||

| Region central | −1.07 | 0.71 | −1.49 | 0.13 | −0.24 | 0.15 | |

| Region west | −1.03 | 0.81 | −1.27 | 0.20 | −0.23 | 0.17 | |

| Sex female | 0.32 | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 1.44 |

| Age | 0 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.92 | 0 | 0 | 1.48 |

| Education literate | 0.96 | 0.80 | 1.20 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 1.41 |

| Size of the herd owned | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.88 | 0.38 | 0 | 0 | 1.23 |

| More than one herder involved in herding | 0 | 0.62 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.20 |

| Prefer source of income (others) | −0.39 | 0.63 | −0.06 | 0.53 | −0.08 | 0.13 | 1.11 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dorji, N.; Derks, M.; Groot Koerkamp, P.W.G.; Bokkers, E.A.M. The Future of Yak Farming from the Perspective of Yak Herders and Livestock Professionals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104217

Dorji N, Derks M, Groot Koerkamp PWG, Bokkers EAM. The Future of Yak Farming from the Perspective of Yak Herders and Livestock Professionals. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104217

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorji, Nedup, Marjolein Derks, Peter W.G. Groot Koerkamp, and Eddie A.M. Bokkers. 2020. "The Future of Yak Farming from the Perspective of Yak Herders and Livestock Professionals" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104217

APA StyleDorji, N., Derks, M., Groot Koerkamp, P. W. G., & Bokkers, E. A. M. (2020). The Future of Yak Farming from the Perspective of Yak Herders and Livestock Professionals. Sustainability, 12(10), 4217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104217