Abstract

Consumers are increasingly concerned about the way their food is produced. This is particularly relevant in the case of meat, due to the impacts that its production methods can have on greenhouse gas emissions and its role in climate change. In relation to this issue, the purpose of our research is to obtain more information on the consumer decision-making process for beef, in order to determine the relative importance of sustainability claims and traditional attributes, and identify consumer profiles with similar perceptions and intentions. A choice experiment was used to assess the influence of these attributes on consumers’ purchasing decisions. The results reveal that the best purchase choice for the consumer would be organic beef, produced in Spain, with an animal welfare label and eco-labelled. Later on, a cluster analysis was carried out using consumer beliefs and attitudes towards meat consumption as inputs, together with purchasing behaviour variables. A solution was obtained with three well-defined consumer segments showing different preference patterns: Cluster 1 (Male millennials indifferent towards environment or sustainability), Cluster 2 (Sustainability-concerned mature women) and Cluster 3 (Middle-aged meat eaters with established families). The results of this study are relevant to develop more appropriate strategies that may be adapted to the behaviour and expectations of eco-friendly food consumers.

1. Introduction

During the recent years, there has been a growing public interest in food products produced using sustainable or ethical production methods [1]. In this regard, the increased demand for environmentally-friendly food products is associated with a growing interest in the sustainable use of resources and thus, in future wellbeing [2]. In general, consumers are increasingly aware of the fact that sustainable consumption is fundamental to protect the natural environment, counteract ongoing climate change, and ensure social justice [3,4]. In this sense, livestock products largely contribute to greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and climate change [5]. Moreover, consumers prefer products identified as sustainable to conventional products based on animal welfare, environmental, or social reasons [6,7]. On the other hand, the extent to which consumers value and respond to environmentally-friendly food products through value-consistent behaviour still remains a questionable point [8].

Such concerns should ideally lead consumers to be willing to pay higher prices for products that have been produced in respect of ethical/environmental attributes, such as animal welfare, health-related features, or aspects related to environmentally-friendly production systems [9]. This is especially relevant in the animal production sector, where many consumers expect animal welfare and other social and ethical attributes to be taken into account in the production processes of these foods [10,11,12].

Furthermore, consumer preferences for meat products are reflected in a multi-factor interaction that is shaped by multiple aspects, both related to marketing and to the sensory properties of meat [13,14,15]. These aspects range from life events, cultural ideas, personal factors, resources, social factors and choice context, as well as personal characteristics [14].

Nowadays, interest in the environmental and social production externalities is increasing and so is the market share of meat products with sustainability labels [16]. Consumers are no longer concerned just with adequate economic returns, but also with environmental sustainability [17]. Consequently, there has been a tendency for consumers to become more environmentally conscious, and therefore for more willingness to contribute to environmental protection.

The scope of this piece of research is to analyse various attributes involved in the purchasing decision of meat with special attention to those that are based on the production method, sustainability and animal welfare. In contrast with the large number of studies that only analysed the willingness to pay (WTP) for animal welfare or sustainability attributes [18,19,20], only a few studies have segmented consumers according to preference for a broader range of sustainability-related attributes (animal welfare, environmental impact, and production method) as well as for the more traditional product characteristics (e.g., country of origin and price) [21,22,23].

Several alternatives are available for the analysis of consumer preferences [24] with choice experiment (CE) being one of the most relevant techniques, due to its capacity to study preferences for “complex goods”, as it is the case of food products. Conditional logit, a model of CE, has been applied in this paper [25,26,27]. In this sense, the use of the CE to evaluate consumer preferences towards meat attributes has been reported by various authors [28,29,30,31,32,33].

Within this framework, the main purposes of this paper are: (i) to gain more insights on the consumer decision-making process for purchasing beef; (ii) to determine the relative importance of sustainability claims and traditional attributes underlying the purchasing intention of Spanish consumers of beef, by applying the CE technique; (iii) to identify the profiles of beef consumers with similar perceptions and intentions; and (iv) to characterise these profiles according to their socio-economic features and behaviour.

This paper is structured as follows. First of all, the following section presents a literature review on the concepts of sustainability claims and food purchasing. Subsequently, Section 3 details the data collection procedure and methodology applied for this piece of research. In Section 4, the paper deals with the main findings of this piece of research and discusses them in light of previous research on the topic. Finally, Section 5 outlines the main conclusions of the study and indicates some recommendations for stakeholders, together with guidelines to improve future research.

2. Literature Review

Literature on environmental sustainability labels has improved the understanding about what may lead consumers to choose such labels and the corresponding products. For example, researchers [34] reported that a sustainability label is the most efficient method to increase consumer ability to choose an environmentally friendly food product. Other studies [35,36] also showed that many consumers are displaying increased awareness and preference for environmental sustainability, as well as a greater willingness to pay for socially and environmentally-responsible labelled products.

Ecolabelling is an increasingly used tool being applied to differentiate food production and stimulate informed purchasing decisions, thus creating economic incentives for producers to adopt environmentally friendlier technologies. Food products with eco-labels have been found to be preferred by consumers [37,38]. Moreover, a study [39] has shown that consumer stated preferences for eco-labelled goods increase with environmental consciousness and decrease with price-orientation. In addition, it was revealed [40] that consumer desire to preserve the environment is a key concern when choosing eco-labelled products.

In this context, over the last three decades various product standards certifying sustainable production and labels communicating sustainability-related information about the production method of food products have been put in place [41]. The standard of organic production has been one of the most widely known to consumers, both in Europe and the rest of the world, with organic food products becoming suitable examples of sustainable food due to their lower environmental impact [42,43].

Researchers [21] found that consumers place increasing importance on the extrinsic quality attributes of meat products in response to rising concerns on safety, health, convenience, ethical factors, etc. Nevertheless, a study carried out with European consumers on their awareness of sustainability issues—such as carbon footprint, animal welfare, or Fair Trade—found that consumer concern does not necessarily translate into purchasing behaviour, due to the various trade-offs consumers need to consider when shopping. Furthermore, a lack of transparency, credibility, and availability of information about ethical characteristics of production can also reduce the role of ethical product attributes in decision-making [44].

In parallel to the development of markets for sustainable food products, the geographical origin of food has become more important for consumers. Consumer preferences for the country of origin (COO) have been studied in various contexts [45,46,47]. Moreover, a recent study showed that COO might be an important product attribute to target a wider range of consumers and to differentiate markets for sustainable food products [1]. However, some consumer segments that are interested in sustainable production have also been found to place little importance on COO [1,48].

In addition, there is plenty of evidence that COO affects consumer food choices and that consumers are more willing to buy food products originating in some countries than in others [49,50]. Nonetheless, knowledge about the COOs that are preferred by consumers for their food remains insufficient and seems to differ by food product type [51].

Furthermore, previous studies suggested that animal welfare was a significant determinant and an important reason for the purchase of eco-friendly produced foods [52,53]. Animal welfare is receiving increased attention by consumers and is seen as an emerging quality attribute that is linked to specific food products such as beef, with many exporting countries often having this type of certification available [47]. Consumers are concerned about the way animals are bred, fed, and how animals are taken care of. However, animal welfare is often not the most important choice attribute in meat [54].

Finally, price is another important extrinsic factor that can affect consumer purchase decisions [55]. Moreover, price sensitivity has been reported to be of great influence in consumer decisions, as people with higher price sensitivity may compromise their environmental concerns to choose cheaper but less environmentally-friendly products [56]. However, a recent study showed that consumers who were less sensitive to price, shifted their attention from product appearance and price to environmental aspects, when evaluating eco-labelled products [57].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Procedure and Data Collection

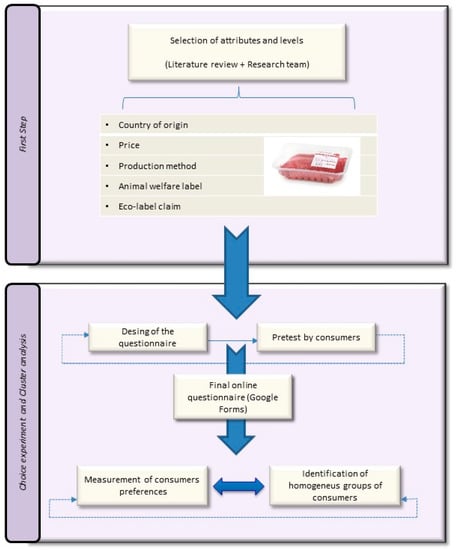

The data used in order to develop the present study were obtained from an online survey carried out in Extremadura, a region in southwest (SW) Spain. The region was selected to be representative of Spain, because its socio-demographics are similar to the Spanish Census of Population and also because it has some characteristics that were considered of potential interest, as it is one of the main beef production areas in Spain and with highly relevant extensive and sustainable livestock production systems. Figure 1 presents the methodological procedure followed for this piece of research.

Figure 1.

Methodological procedure.

The survey was designed and distributed using Google Forms (www.docs.google.com), which was chosen for its flexibility and benefits for the development of surveys. Even though, according to a study [58], online surveys present important advantages (i.e., lower research costs and little time-consuming for respondents), this data collection technique might introduce some bias in terms of overrepresentation of some socio-demographic characteristics, which limits the potential inference of its results.

The sample was designed as a random stratified model, proportionally weighted against the gender and age of the population in Extremadura, with the final sample including 285 valid completed questionnaires. The maximum margin of error was 5.9% at a 95% confidence level.

Data were collected during March 2020, and respondents were recruited from databases that had been created from previous marketing studies conducted by the research team. The online questionnaire was organised in five sections to measure the following aspects: (a) purchasing habits of meat; (b) personal concerns for the environment; (c) lifestyle and willingness to pay for meat; (d) choice experiment and consumer preferences; and (e) socio-demographics aspects. The questionnaire was pre-tested on a sample of 12 individuals (not included in the final sample) to detect any possible misinterpretation, error, or duplication. Adjustments were made to the final questionnaire based on this test. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the final sample compared with those of the population of Extremadura.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample compared to the population of Extremadura.

3.2. Choice Experiment

In order to analyse consumer preferences for meat attributes, a choice experiment approach was carried out in this piece of research. CE is a technique used to analyse consumer preferences for various product attributes [60]. Due to its potential, CE has been widely applied in studies dealing with the analysis of individual preferences for food, including meat [28,29,30,31,32,33,61,62].

CE is based on Lancaster’s consumer theory [63] and assumes that the utility that a consumer obtains from a product derives from the attributes that make it up, and which, therefore, affect his/her purchasing decisions. In a CE, participants are provided with alternative configurations of the product being assessed and are asked to choose between the range of options. The selection of the attributes—and their levels—that will define the product is a key stage which must display the product characteristics and dimensions that are most relevant regarding the consumer’s purchase decision process.

Compared to other methods used to analyse consumer preferences (e.g., contingent valuation, experimental auctions), CE has the advantage of resembling a real purchasing situation [36,62]. The CE approach also allows to explore how attributes are related to each other, even though respondents are not asked to directly answer how important each attribute is for them [47].

For this piece of research, the attributes and levels to be used in CE were selected after a review of the existing literature in consumer preferences for meat [12,13,15,30,33,45,61,64] and according to preliminary research. The attributes finally selected for the study and their corresponding levels are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Beef attributes and their various levels.

Although the study had a main focus on meat in general, it was considered that it should be narrowed down to a specific type of meat that the participants could assess more easily. Therefore, the product presented to the participants in the CE was pre-packaged sliced beef (500-g tray). Beef was chosen not only for being one of the most popular meats in Spain in terms of consumption, but also because it is one of the most targeted meats for its contribution to climate change. Therefore, the improvement of sustainability in its production processes could be highly valued by consumers.

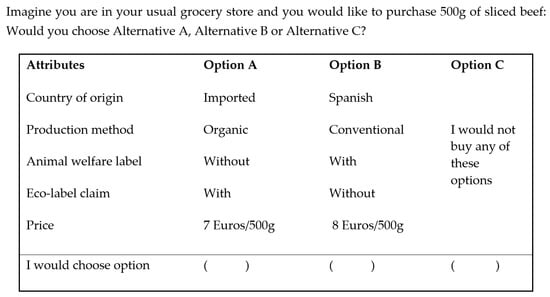

After the selection of the attributes and levels, these are merged to create hypothetical products, which are later on combined in pairs to create a choice set. Each choice set consisted of three alternatives: alternative product A, alternative product B, and the “no purchase” option, which allowed the participants to choose none of the products offered (see Figure 2 for an example). Based on the chosen attributes/levels, the total number of hypothetical products would have been 48 (2×3×2×2×2) with 2256 (48×47) possible combinations. As this figure was considered to be too large for participants to evaluate, an orthogonal fractional factorial design was used to reduce the number of comparisons, with 8 choice sets being finally presented to the participants. The order of presentation and allocation to respondents of the various choice sets was randomised. Figure 2 presents an example of choice set.

Figure 2.

Example of a choice set.

3.3. Conditional Logit

Conditional logit, a model based on the Random Utility Theory [25,26,27], has been applied in this paper to assess consumer preferences. The clogit module of R statistical package version 3.6.3, was used, following the guidelines described previously [65]. Base levels have been defined for all the qualitative attributes, which allow to set a zero-utility level with respect to the other levels of the attribute. The selected base levels were “Imported” (for the attribute Country of origin), “Conventional” (for Production method), “Without” (for Animal Welfare Label), and “Without” (for Eco-label claim).

The econometric specification is therefore defined as follows:

The inclusion of price as an attribute in a choice experiment allows to calculate the marginal substitution ratio between a coefficient and the price, that is, the willingness to pay for the specific attribute. WTP is calculated as follows:

Therefore, WTPk reflects the amount of money that a consumer would be willing to pay to go from the base level to the level of the attribute k provided by the product.

3.4. Cluster Analysis

The identification of subgroups of consumers with similar preference behaviour towards sustainable meat was considered to be a valuable finding of this research. Therefore, a k-means cluster analysis was carried out with the Cluster module of IBM SPSS Statistics v 21.

The inputs used were variables related to beliefs and attitudes towards meat production/consumption and environment, together with others measuring purchasing habits and following the procedure developed previously [66]. Although various solutions were checked, a 3-cluster solution was finally chosen, due to the groups generated being adequate in size and being of the highest statistical significance.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Choice Experiment Model

Table 3 shows the aggregate results of the conditional choice model. The value of the coefficient of each level indicates the utility added (positive sign) or detracted (negative sign) to or from the reference level.

Table 3.

Results of the choice model for the whole sample.

The results in Table 3 show that all the attributes (except price) have a positive impact with respect to their reference levels on the utility of the respondents. For example, the results for the “Country of origin” attribute indicate that consumers obtain more utility when choosing beef produced in Spain than imported beef. Something similar happens with organic production or the presence of animal welfare and eco-labels, which have a positive impact on the preferences of respondents compared to their baseline reference levels.

These results are in consonance with those found by other researchers [67], who reported that consumers showed greater preference for local food products than for imported ones. Researchers [68] mentioned that one of the main drivers of consumer preferences and attitudes towards foods is the country of origin. Moreover, another study [21] found that the origin of beef was the most important piece of information demanded by European consumers.

On the other hand, there are studies which indicate that consumer concern about animal welfare is the most important factor when purchasing meat products [69,70]. In a similar way, some researchers [71] found that organic production is very relevant for consumers when buying meat, while others [72] found that 74% of European participants preferred animal-friendly meat to conventional meat.

In addition, the fact that the sign of the price attribute is negative indicates that, as the price of beef decreases, its utility for consumers increases. This means that the probability of choosing a product with a lower price is higher, a result that is consistent with the habitual behaviour of demand. These results are in line with those reported by other researchers [73], who found that the higher price of eco-friendly food products is often perceived as a limiting factor for the purchase of these products.

4.2. Consumer Segmentation

Table 4 presents the detailed socio-demographic characteristics and purchasing habits of the three segments that were generated by the cluster analysis, together with those of the general sample. It also shows the results of Chi-squared tests carried out to look for significant differences between the clusters.

Table 4.

Descriptions of the clusters and the general sample by socio-demographic characteristics and purchasing habits (%).

Table 5 shows the data regarding beliefs and attitudes towards meat consumption/production and environment of the three clusters and the general sample.

Table 5.

Descriptions of the clusters and the general sample regarding beliefs and attitudes towards meat production/consumption and environment (%).

This information is complementary to that presented in Table 4 and allows to better define consumer typologies:

- Cluster 1 (Male millennials indifferent towards environment or sustainability). This segment has the highest percentage of men and of people under 36 years old. This group has the lowest level of consumption of environmentally-friendly products, but also has the poorest scores on all variables relating to environmental and sustainable behaviour, despite its high level of education.

- Cluster 2 (Sustainability-concerned mature women) displays the largest percentages of women and mature consumers (over 50 years of age). This cluster has the highest frequency of consumption of environmentally-friendly products, and it is also the one that gives the greatest scores to aspects relating to the environment and sustainability. It is also the group with the lowest consumption of meat.

- Cluster 3 (Middle-aged meat eaters with established families) presents the highest percentages of consumers between 36 and 50 years and of larger family units. It also has the highest frequency and level of meat consumption (which can be related to family size). Their members are middle ground, in terms of their attitudes towards sustainability and the environment.

4.3. Consumer Preferences Within Each Cluster

Once the clusters had been identified, CE was carried out again for each of the consumer groups. Table 6 lists the results of the choice model for each cluster.

Table 6.

Results of the choice model for each cluster.

Consumers in Cluster 1 are characterised by showing no significant preference between organic or conventional beef production. They look for beef with animal welfare label although they show the lowest preference for beef with eco-labels. Noticeably, they are the most price-sensitive group of the whole sample, a fact that could relate to their lower income level. These results are consistent with those reported by other researchers [44] who found that price-sensitive segments are slightly overrepresented by men. Additionally, a previous study [74] mentioned that price seems to have a higher impact than logo and/or label when purchasing meat products. It is also well known that attitudes and behaviour towards sustainable food consumption differ in multiple ways between genders [75].

Cluster 2 shows the highest preference of the three clusters for organic production and for the purchase of beef with animal welfare label and eco-label; these results are consistent with the sustainability concerns of the cluster. Consumers in this group also present the lowest sensitivity to price of the entire sample. These results are in agreement with those found by other researchers [76] who stated that women generally show higher willingness to pay for environmentally-friendly food products. These findings are also in line with previous research where female participants declared higher levels of sustainable consumption compared with male participants [75]. Moreover, a previous study [77] found that, with higher levels of education, men revealed increased meat consumption, while women showed reduced consumption. However, and contrary to other studies conducted in other European countries, a study [78] found that men showed more environmental concern and more positive outlook towards green purchase compared with women.

Finally, Cluster 3 shows similar preferences to those obtained for the overall sample. In this group, consumers have the highest preference for the Spanish origin, a behaviour that could be related to their age structure (middle-aged consumers) and to the fact that they have children in their families. As many prior studies have noted, the preference for national/local food products is quite common, so that consumers are usually willing to pay a premium price for domestic and local food [49,79].

When making food purchasing choices, consumers can rely on those attributes that are most important to them or make trade-offs amongst a range of attributes [80]. Moreover, they also need to make trade-offs between both positive benefits—such as animal welfare—and (additional) price [81,82]. In addition, it has been found that consumers who show preference for food products associated with ethic-related claims are those who are also genuinely concerned about environmental sustainability [83]. Moreover, a prior study [84] mentioned that providing detailed information about beef processing technology increased consumer acceptability of beef products. It seems clear that label information does more than just provide product-related knowledge to consumers, as it affects their acceptance and purchase intention with respect to the corresponding beef products. Finally, another study [85] showed that beef labels are important sources of information about meat quality for consumers.

4.4. Willingness to Pay

One of the most interesting aspects of choice experiments, when price is included as an attribute, is the possibility of determining the WTP or the implicit price for each attribute. The WTP should be understood as the difference in euros between the price the consumer is willing to pay for a particular level, in comparison to the baseline reference level. Table 7 presents the WTP for the overall sample and for each of the clusters.

Table 7.

Willingness to pay for the overall sample and for each cluster (€/500 g).

The explanation of the results shown in Table 7 is that the respondents in the overall sample would be willing to pay € 4.71/500 g more for a beef produced in Spain compared to imported beef, or that they will pay € 1.36/500 g more for organic beef compared to beef produced by conventional production means. These results are consistent with those reported by researchers [23] who indicated high consumer preference and WTP for local food. A study [86] reported that consumers were ready to pay premium prices for food products deriving from quality production methods. Additionally, researchers [87] found that consumers in Italy were willing to pay a premium price for organic beef, with similar results also being reported by others [88].

On looking at the figures for the various clusters, we can deduce that they are in agreement with their previously defined characteristics. Thus, consumers in Cluster 1 present the lowest willingness to pay for all the attributes under analysis (they were very price-sensitive), while consumers in Cluster 2 show the highest willingness to pay, which is consistent with the low importance they placed on price. In this context, a recent study [89] revealed that consumers are willing to pay a price premium of approximately 20% for carrots and strawberry jams, if these products are eco-friendly labelled. Similar findings have also been reported for wine [90] and coffee [91]. However, other researchers [92] found that gender affected the understanding of sustainability labels and indicated that young male consumers had a better understanding of such labels.

In this sense, it should be noted that many consumers actually have little understanding of the real meaning of sustainability labels [93]. In this sense, lack of comprehension of the labels could lead to consumers processing information about the claim incompletely or incorrectly [94], resulting in misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

5. Conclusions

Public interest in sustainability issues has grown significantly in recent years due to growing awareness of climate change and the environment. Thus, an increasing number of consumers are concerned about the environmental, ethical, and animal welfare impact of their food. In this context, this study has explored consumer preferences and willingness to pay for sustainable and environmental attributes of beef, using a choice experiment.

As stated in this paper, one of the contributions of this study is the segmentation of consumers based on their preferences for a wide range of sustainability-related attributes (animal welfare, environmental impact, and production method) and other more traditional product characteristics (country of origin and price). This is in contrast with most consumer studies that have essentially analysed the willingness to pay for animal welfare or sustainability attributes. The selection of these variables was based on a preliminary review of the literature, which identified potential items to include in the survey. Subsequently, those items that were considered most relevant were selected to generate information on the previously mentioned aspects.

A conditional logit model showed that consumers preferred beef which had been organically produced in Spain, bearing an animal welfare label as well as eco-labelled. In addition, a cluster analysis was carried out using variables relating to beliefs and attitudes towards meat production/consumption and the environment, along with others that measure purchasing habits, resulting in three well-defined clusters. In this sense, “the Indifferent millennials”, the most numerous group, proved to be the cluster that least consumes environmentally-friendly products, as well as having the worst environmental and sustainable behaviour. On the other hand, the “Sustainability-concerned women” presents the highest percentage of mature consumers, with the largest frequency of consumption of environmentally-friendly products, but with the lowest consumption of meat. Finally, Cluster 3 (Middle-aged meat eaters) includes consumers with the highest frequency and level of meat consumption and who are middle ground in terms of their attitudes towards sustainability and the environment.

This study will help develop more appropriate strategies to understand the behaviour and expectations of eco-friendly food consumers. Nonetheless, given the monetary constraints that prevented the study from being carried out nationwide, we regard our findings as not fully inferable to the rest of the population. In this sense, future research should aim at obtaining a deeper insight into certain consumer segments. This would allow an exhaustive analysis of the various environmental labels available in order to measure the willingness to pay and to discriminate the real importance that consumers attribute to the sustainable quality of a product. In the future, these aspects will positively contribute to clarify new patterns of consumption and their incidence in the production systems, as well as in the implementation of incentive policies for a more responsible consumption.

Author Contributions

This study is the result of collaborative work among the authors with the following contributions: conceptualization, A.E. and F.J.M.; methodology, A.E. and M.E.; validation, formal analysis, F.J.M. and A.E.; research, A.E.; resources, F.J.M.; data curation, M.E.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.M. and A.E.; writing—review and editing, A.E.; visualization, M.E.; supervision, F.J.M. and M.E.; project administration, A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and funding provided by the Junta de Extremadura (Extremadura Regional Council) and FEDER Funds (Grant GR18098), which made the translation and publication of this piece of research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Risius, A.; Hamm, U.; Janssen, M. Target groups for fish from aquaculture: Consumer segmentation based on sustainability attributes and country of origin. Aquaculture 2019, 499, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, L.; Eberle, U.; Lorek, S. Sustainable food consumption: An overview of contemporary issues and policies. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, A.; Mesias, F.J.; Elghannam, A.; Escribano, M. Can extensification compensate livestock greenhouse gas emissions? A study of the carbon footprint in Spanish agroforestry systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 200, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, A.; Mesias, F.J.; Escribano, M. Perception of Spanish consumers towards environmentally friendly labelling in food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Balderjahn, I.; Buerke, A.; Kirchgeorg, M.; Peyer, M.; Seegebarth, B.; Wiedmann, K.-P. Consciousness for sustainable consumption: Scale development and new insights in the economic dimension of consumers’ sustainability. AMS Rev. 2013, 3, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joerß, T.; Akbar, P.; Mai, R.; Hoffmann, S. Conceptualizing sustainability from a consumer perspective Konzeptionalisierung der Nachhaltigkeit aus der Konsumentensicht. uwf UmweltWirtschaftsForum 2017, 25, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljenstolpe, C. Evaluating animal welfare with choice experiments: An application to Swedish pig production. Agribusiness 2008, 24, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, B.K.; Oosting, S.J.; Bock, B.B. Elements of societal perception of farm animal welfare: A quantitative study in The Netherlands. Livest. Sci. 2006, 104, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonsor, G.T.; Olynk, N.; Wolf, C. Consumer Preferences for Animal Welfare Attributes: The Case of Gestation Crates. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2009, 41, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M.; Verbeke, W. Consumers’ valuation of sustainability labels on meat. Food Policy 2014, 49, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clonan, A.; Wilson, P.; Swift, J.A.; Leibovici, D.G.; Holdsworth, M. Red and processed meat consumption and purchasing behaviours and attitudes: Impacts for human health, animal welfare and environmental sustainability. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2446–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Andrade, J.C.; de Aguiar Sobral, L.; Ares, G.; Deliza, R. Understanding consumers’ perception of lamb meat using free word association. Meat Sci. 2016, 117, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Font-i-Furnols, M.; Guerrero, L. Consumer preference, behavior and perception about meat and meat products: An overview. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuepper, D.; Clemm, A.; Wree, P. The preference for sustainable coffee and a new approach for dealing with hypothetical bias. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2019, 158, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Ng, A. Environmental and Economic Dimensions of Sustainability and Price Effects on Consumer Responses. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, G.A.; Zimmermann, J.; Visschers, V.H.M.; Siegrist, M. Does environmental friendliness equal healthiness? Swiss consumers’ perception of protein products. Appetite 2016, 105, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, A. Australian consumers’ food-related environmental beliefs and behaviours. Appetite 2008, 50, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Bartels, J.; Dagevos, H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G. Segments of sustainable food consumers: A literature review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernués, A.; Olaizola, A.; Corcoran, K. Extrinsic attributes of red meat as indicators of quality in Europe: An application for market segmentation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2003, 14, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Verbeke, W.; van Poucke, E. Segmentation based on consumers’ perceived importance and attitude toward farm animal welfare. Int. J. Sociol. 2007, 15, 84–100. [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann, C.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ perceptions and preferences for local food: A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallas, Z.; Lambarraa, F.; Gil, J.M. A stated preference analysis comparing the Analytical Hierarchy Process versus Choice Experiments. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D.; Train, K. Mixed MNL models for discrete response. J. Appl. Econom. 2000, 15, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In Frontiers Econometrics; Zarembka, P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. 105–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hensher, D.A.; Rose, J.; Greene, W.H. The implications on willingness to pay of respondents ignoring specific attributes. Transportation 2005, 32, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalak, A.; Abiad, M. How effective is information provision in shaping food safety related purchasing decisions? Evidence from a choice experiment in Lebanon. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 26, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Anders, S.; An, H. Measuring consumer resistance to a new food technology: A choice experiment in meat packaging. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, A.; De-Magistris, T. Preferences for lamb meat: A choice experiment for Spanish consumers. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, A.; Loureiro, M.L.; Nayga, R.M. Consumers’ valuation of nutritional information: A choice experiment study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koistinen, L.; Pouta, E.; Heikkilä, J.; Forsman-Hugg, S.; Kotro, J.; Mäkelä, J.; Niva, M. The impact of fat content, production methods and carbon footprint information on consumer preferences for minced meat. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 29, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.L.; Umberger, W.J. A choice experiment model for beef: What US consumer responses tell us about relative preferences for food safety, country-of-origin labeling and traceability. Food Policy 2007, 32, 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, G.A.; Visschers, V.H.M.; Siegrist, M. How to improve consumers’ environmental sustainability judgements of foods. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, S.M.; Winer, R.S. The role of the beneficiary in willingness to pay for socially responsible products: A meta-analysis. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sama, C.; Crespo-Cebada, E.; Díaz-Caro, C.; Escribano, M.; Mesías, F.J. Consumer Preferences for Foodstuffs Produced in a Socio-environmentally Responsible Manner: A Threat to Fair Trade Producers? Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnmann, J.; Asche, F. The Value of Product Attributes, Brands and Private Labels: An Analysis of Frozen Seafood in Germany. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 67, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffry, S.; Pickering, H.; Ghulam, Y.; Whitmarsh, D.; Wattage, P. Consumer choices for quality and sustainability labelled seafood products in the UK. Food Policy 2004, 29, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, I. Ecolabeling, consumers’ preferences and taxation. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2202–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempton, W. Lay perspectives on global climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 1991, 1, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janßen, D.; Langen, N. The bunch of sustainability labels—Do consumers differentiate? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkat, K. Comparison of Twelve Organic and Conventional Farming Systems: A Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions Perspective. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 620–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werf, H.M.G.; Tzilivakis, J.; Lewis, K.; Basset-Mens, C. Environmental impacts of farm scenarios according to five assessment methods. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 118, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Policy 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, K.; Bradley, D.; Fraser, I.; Hussein, M. Consumer preferences regarding country of origin for multiple meat products. Food Policy 2016, 64, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrenova, F.V.; Grabner-Kräuter, S.; Terlutter, R. Country-of-origin (COO) effects in the promotion of functional ingredients and functional foods. Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Hong, S.J.; Wang, H.H.; Wu, L. Emerging markets for imported beef in China: Results from a consumer choice experiment in Beijing. Meat Sci. 2016, 121, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Tong, C. Organic or local? investigating consumer preference for fresh produce using a choice experiment with real economic incentives. HortScience 2009, 44, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, C.L.; Turri, A.M.; Howlett, E.; Stokes, A. Twenty Years of Country-of-Origin Food Labeling Research: A Review of the Literature and Implications for Food Marketing Systems. J. Macromark. 2014, 34, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Pedersen, S.; Paternoga, M.; Schwendel, E.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. How important is country-of-origin for organic food consumers? A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 542–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, C.; Hamm, U. Local and/or organic: A study on consumer preferences for organic food and food from different origins. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmar, U. Consumers’ purchase of organic food products. A matter of convenience and reflexive practices. Appetite 2011, 56, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui-Essoussi, L.; Sirieix, L.; Zahaf, M. Trust orientations in the organic food distribution channels: A comparative study of the Canadian and French markets. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocella, G.; Hubbard, L.; Scarpa, R. Farm animal welfare, consumer willingness to pay, and trust: Results of a cross-national survey. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2010, 32, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockshin, L.; Jarvis, W.; d’Hauteville, F.; Perrouty, J.P. Using simulations from discrete choice experiments to measure consumer sensitivity to brand, region, price, and awards in wine choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Lessem, N. Eco-Premium or Eco-Penalty? Eco-Labels and Quality in the Organic Wine Market. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 318–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Lim, Y.; Chang, P.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Lehto, M.R.; Cai, H. Ecolabel’s role in informing sustainable consumption: A naturalistic decision making study using eye tracking glasses. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.B. Researching Internet-Based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services. J. Comput. Commun. 2006, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanish Statistical Institute. INEbase Population and Housing Census; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Schroeder, T.C. Effects of label information on consumer willingness-to-pay for food attributes. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2009, 91, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Kallas, Z.; Costa-Font, M.; Gil, J.M.; Realini, C.E. Impact of hedonic evaluation on consumers’ preferences for beef attributes including its enrichment with n-3 and CLA fatty acids. Meat Sci. 2016, 111, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Caro, C.; García-Torres, S.; Elghannam, A.; Tejerina, D.; Mesias, F.J.; Ortiz, A. Is production system a relevant attribute in consumers’ food preferences? The case of Iberian dry-cured ham in Spain. Meat Sci. 2019, 158, 107908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.J. A New Approach to Consumer Theory. J. Polit. Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realini, C.E.; Font i Furnols, M.; Sañudo, C.; Montossi, F.; Oliver, M.A.; Guerrero, L. Spanish, French and British consumers’ acceptability of Uruguayan beef, and consumers’ beef choice associated with country of origin, finishing diet and meat price. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizaki, H.; Nishimura, K. Design and Analysis of Choice Experiments Using R: A Brief Introduction. Agric. Inf. Res. 2008, 17, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesías, F.J.; Escribano, M.; Rodríguez de Ledesma, A.; Pulido, F. Market segmentation of cheese consumers: An approach using consumer’s attitudes, purchase behaviour and sociodemographic variables. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2003, 56, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R. Country of origin—A consumer perception perspective of fresh meat. Br. Food J. 2000, 102, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Hu, W.; Maynard, L.J.; Goddard, E. A Taste for Safer Beef? How Much Does Consumers’ Perceived Risk Influence Willingness to Pay for Country-of-Origin Labeled Beef. Agribusiness 2014, 30, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Meeting Heterogeneity in Consumer Demand for Animal Welfare: A Reflection on Existing Knowledge and Implications for the Meat Sector. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2013, 26, 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Verbeke, W.; Van Poucke, E.; Tuyttens, F.A.M. Do citizens and farmers interpret the concept of farm animal welfare differently? Livest. Sci. 2008, 116, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgogno, M.; Favotto, S.; Corazzin, M.; Cardello, A.V.; Piasentier, E. The role of product familiarity and consumer involvement on liking and perceptions of fresh meat. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 44, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocella, G.; Kennedy, O. Food health claims—What consumers understand. Food Policy 2012, 37, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, L.; Chrysochou, P.; Krystallis, A.; Thøgersen, J. The role of price as a product attribute in the organic food context: An exploration based on actual purchase data. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 37, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; van der Lans, I.A.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Different shades of grey: Compromise products to encourage animal friendly consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 45, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Pinto, D.; Herter, M.M.; Rossi, P.; Borges, A. Going green for self or for others? Gender and identity salience effects on sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latvala, T.; Niva, M.; Mäkelä, J.; Pouta, E.; Heikkilä, J.; Kotro, J.; Forsman-Hugg, S. Diversifying meat consumption patterns: Consumers’ self-reported past behaviour and intentions for change. Meat Sci. 2012, 92, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Gender differences in Egyptian consumers’ green purchase behaviour: The effects of environmental knowledge, concern and attitude. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, T.; Vecchiato, D. An analysis of the territorial factors affecting milk purchase in Italy. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettman, J.R.; Luce, M.F.; Payne, J.W. Constructive Consumer Choice Processes. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerkvist, C.J.; Hess, S. A meta-analysis of consumer willingness to pay for farm animal welfare. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2011, 38, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Stakeholder, citizen and consumer interests in farm animal welfare. Anim. Welf. 2009, 18, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Samant, S.S.; Seo, H.S. Effects of label understanding level on consumers’ visual attention toward sustainability and process-related label claims found on chicken meat products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 50, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wezemael, L.; Ueland, Ø.; Rødbotten, R.; De Smet, S.; Scholderer, J.; Verbeke, W. The effect of technology information on consumer expectations and liking of beef. Meat Sci. 2012, 90, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunert, K.G.; Bredahl, L.; Brunsø, K. Consumer perception of meat quality and implications for product development in the meat sector—A review. Meat Sci. 2004, 66, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, A.; Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; López-Galán, B. Are Local and Organic Claims Complements or Substitutes? A Consumer Preferences Study for Eggs. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 65, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, R.; Zanoli, R.; Bruschi, V.; Naspetti, S. Inferred and stated attribute non-attendance in food choice experiments. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 95, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, Á.M.; Borchardt, M.; Vaccaro, G.L.R.; Pereira, G.M.; Almeida, F. Motivations for promoting the consumption of green products in an emerging country: Exploring attitudes of Brazilian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K. Verbraucherakzeptanz des Regionalfensters; Thünen-Institut für Marktanalyse: Braunschweig, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedmann, K.P.; Hennigs, N.; Behrens, S.H.; Klarmann, C. Tasting green: An experimental design for investigating consumer perception of organic wine. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörqvist, P.; Haga, A.; Langeborg, L.; Holmgren, M.; Wallinder, M.; Nöstl, A.; Seager, P.B.; Marsh, J.E. The green halo: Mechanisms and limits of the eco-label effect. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Mariani, A.; Vecchio, R. Effectiveness of sustainability labels in guiding food choices: Analysis of visibility and understanding among young adults. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 17, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, K.; Bernard, J.C. The effect of information on consumers’ willingness to pay for natural and organic chicken. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. Current issues in the understanding of consumer food choice. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 13, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).