Urban Blue Acupuncture: A Protocol for Evaluating a Complex Landscape Design Intervention to Improve Health and Wellbeing in a Coastal Community

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

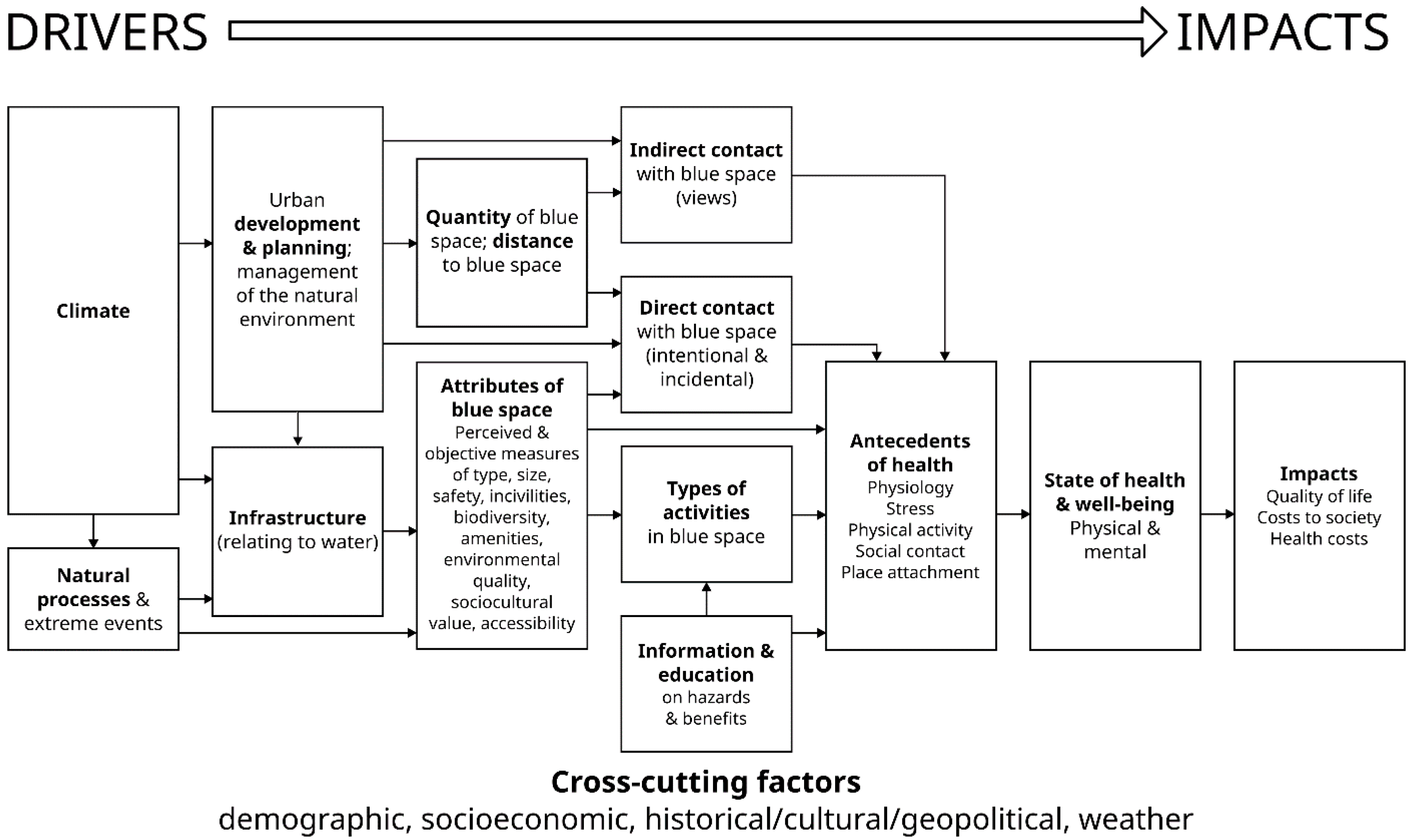

1.2. Conceptual Framework

- 1.

- To what extent does the renovation of a blue space, by adding a small-scale physical intervention and associated public engagement, attract more people: a) to the site; b) to the water?

- 2.

- How might changes to the blue space (or changes in visit characteristics) have a positive impact on community-level health and well-being?

- 3.

- What are the social and economic values of the intervention?

2. The Study Site

2.1. Plymouth

2.2. The Active Neighbourhoods Programme

2.3. Teats Hill

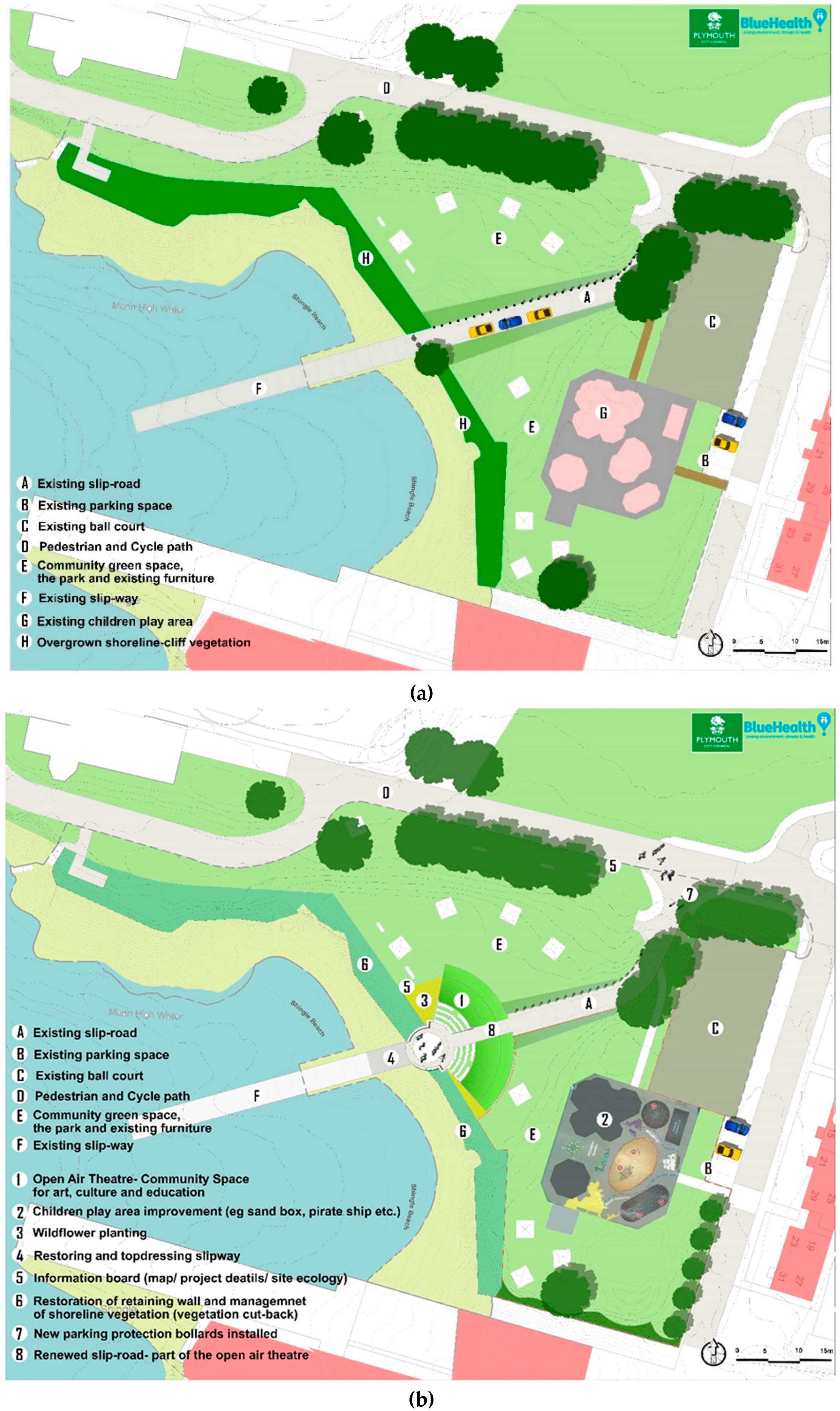

2.4. A Two Pronged (“Complex”) Intervention: A Community Co-Creation Design Process at Teats Hill

3. Research Strategy and Methodology

3.1. Strategy

3.2. Research Methodology

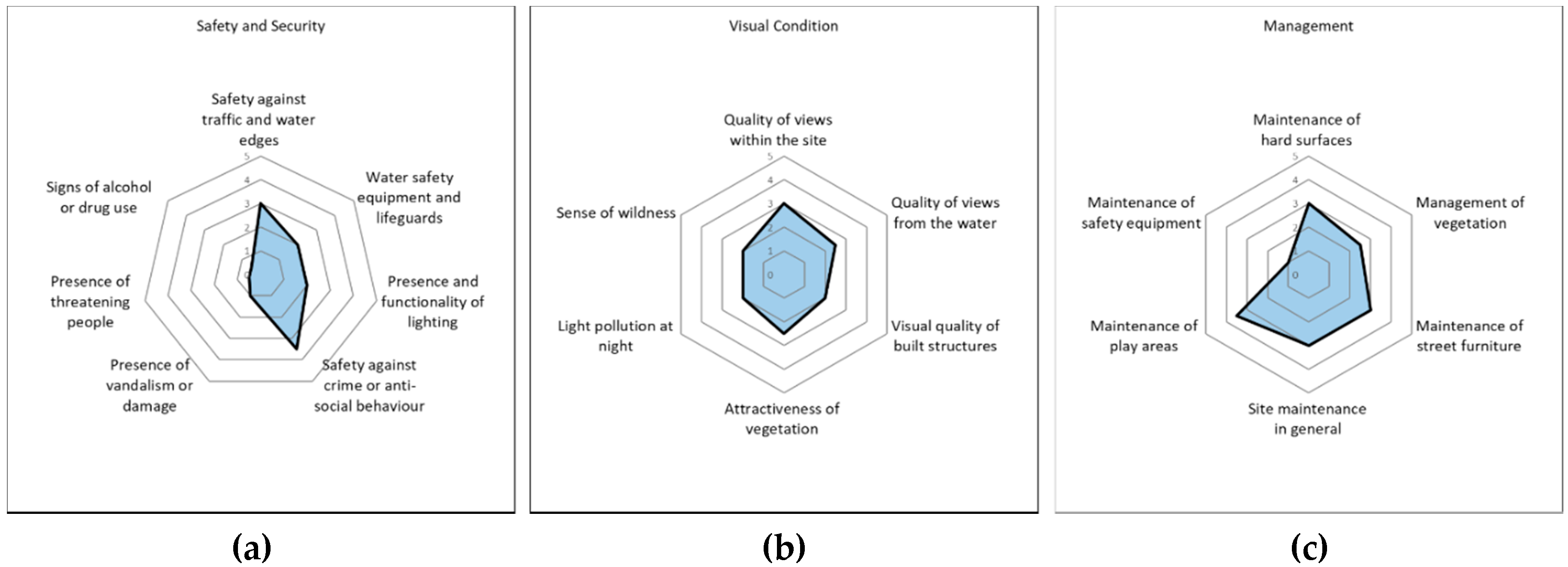

3.2.1. The BlueHealth Environmental Assessment Tool (BEAT)

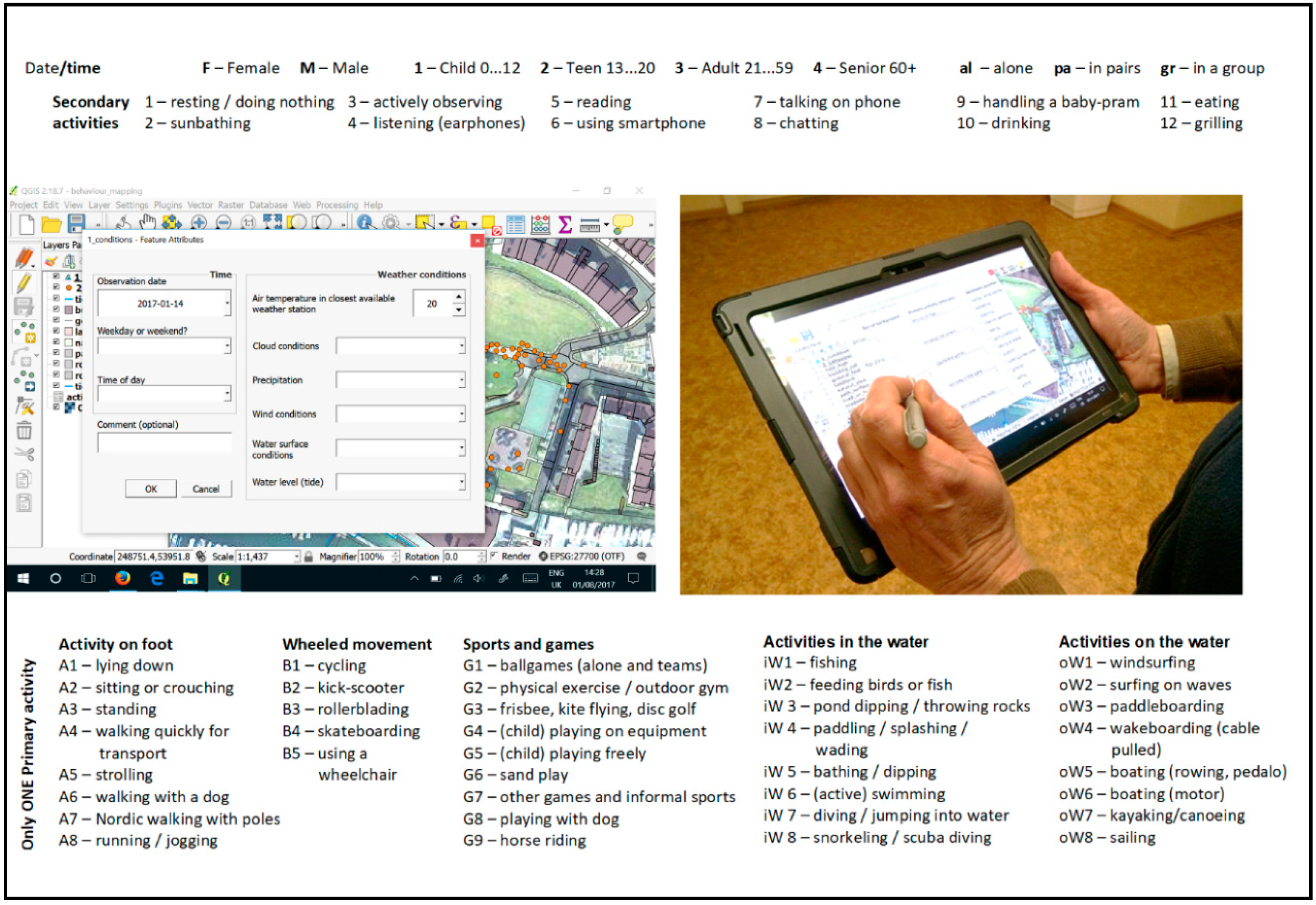

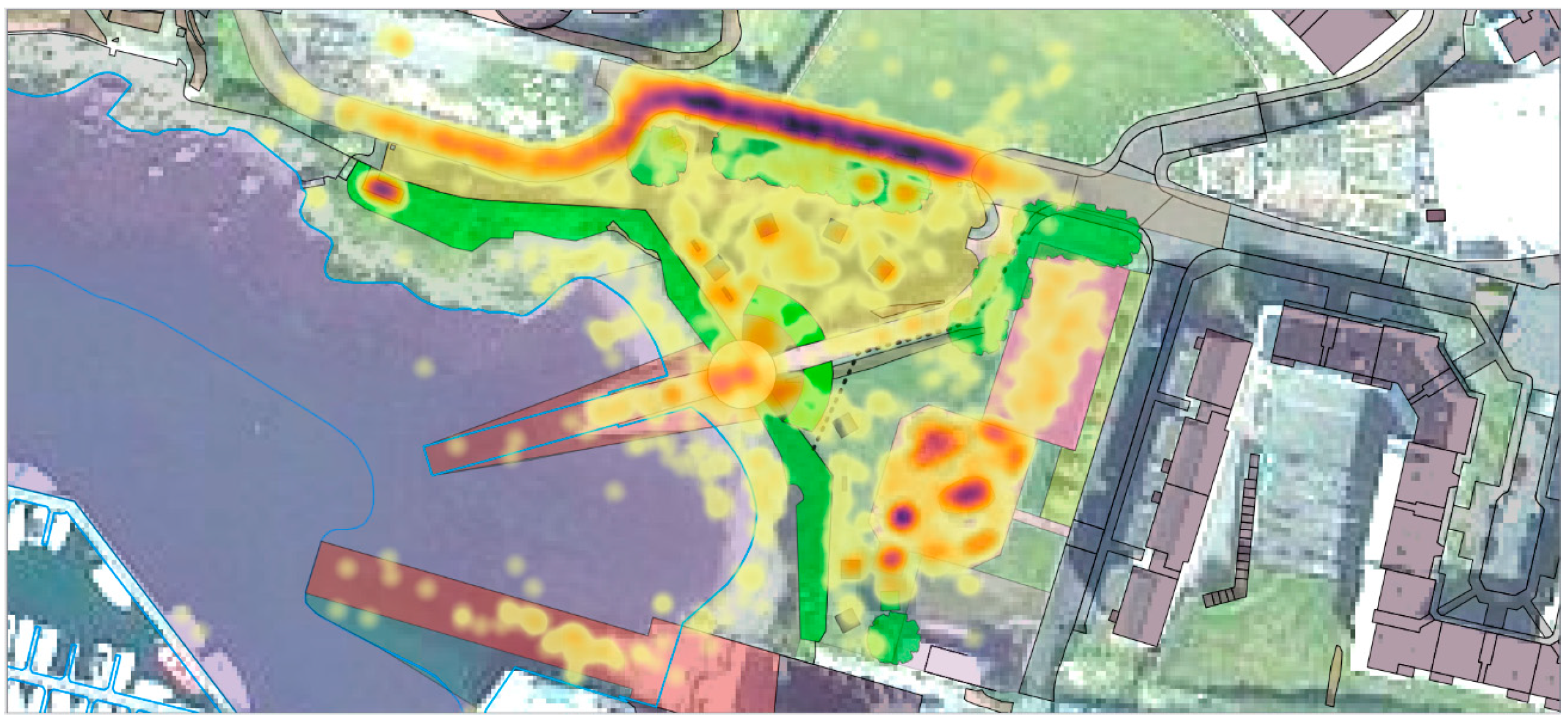

3.2.2. The BlueHealth Behavioural Assessment Tool (BBAT)

3.2.3. BlueHealth Community-Level Survey (BCLS)

3.2.4. BlueHealth Site Interview (BSI)

3.2.5. Ethical Approval

4. Discussion

4.1. Teats Hill in Context

4.2. The Importance of Describing the Protocol

4.3. Issues and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frumkin, H.; Gregory, N.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, P.H., Jr.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; et al. Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.; Rogerson, M. The importance of greenspace for mental health. Bjpsych. Int. 2017, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braubach, M.; Egorov, A.; Mudu, P.; Wolf, T.; Ward Thompson, C.; Martuzzi, M. Effects of Urban Green Space on Environmental Health. Equity Resil. 2017. [CrossRef]

- De Vries, S. Nearby nature and human health: Looking at mechanisms and their implications. In Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space/People Space 2; Ward Thompson, C., Aspinall, P., Bell, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.). Urban Nature for Human Health and Well-Being: A Research Summary for Communicating the Health Benefits of Urban Trees and Green Space; FS-1096; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 24.

- WHO (Regional Office for Europe). Urban Green Spaces and Health; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. Local Action on Health Inequalities: Improving Access to Green Spaces Health Equity; UCL Institute of Health Equity: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Völker, S.; Kisteman, T. The impact of blue space on human health and well-being - Salutogenetic health effects of inland surface waters: A review. International J. Environ. Health 2011, 214, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, S.; Kisteman, T. Developing the urban blue: Comparative health responses to blue and green urban open spaces in Germany. Health Place 2015, 35, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutsford, D.; Pearson, A.L.; Kingham, S.; Reitsma, F. Residential exposure to visible blue space (but not green space) Associated with lower psychological distress in a capital city. Health Place 2016, 39, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Martínez, D.; Dadvand, P.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Plasència, A.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Residential green spaces and mortality. A systematic review. Environ. Int. 2016, 86, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachowycz, K.; Jones, A.P. Greenspace and obesity: A systematic review of the evidence. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2011, 12, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveirinha de Oliveira, E.; Aspinall, P.; Briggs, A.; Cummins, S.; Leyland, A.H.; Mitchell, R.; Roe, J.; Ward Thompson, C. How effective is the Forestry Commission Scotland’s woodland improvement programme—‘Woods in and Around Towns’ (WIAT)—At improving psychological well-being in deprived urban communities? A quasi-experimental study. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Zijlema, W.; Vert, C.; White, M.P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Outdoor blue spaces, human health and well-being: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wüstemann, H.; Kalisch, D.; Kolbe, J. Accessibility of urban blue in German major cities. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 78, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Haeffner, M.; Jackson-Smith, D.; Buchert, M.; Risley, J. Accessing blue spaces: Social and geographic factors structuring familiarity with, use of, and appreciation of urban waterways. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Gottwald, S.; Kuoppa, J.; Kyttä, M. Integrating multiple elements of environmental justice into urban blue space planning using public participation geographic information systems. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 153, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M.; Ylén, M.; Tyrväinen, L.; Silvennoinen, H. Favorite green, waterside and urban environments, restorative experiences and perceived health in Finland. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Wheeler, B.W.; Depledge, M.H. Coastal proximity, health and well-being: Results from a longitudinal panel survey. Health Place 2013, 23, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, B.W.; White, M.; Stahl-Timmins, W.; Depledge, M.H. Does living by the coast improve health and wellbeing? Health Place 2012, 18, 1198–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Roe, J.; Brown, C.; Morris, S.; Morrice, J.; Ward Thompson, C. Blue Health: Water, health and wellbeing, Centre of Expertise for Waters, James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen. 2012. Available online: www.crew.ac.uk/publications (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Gidlow, C.J.; Ellis, N.J.; Bostock, S. Development of the Neighbourhood Green Space Tool (NGST). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 106, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Van den Berg, A.E.; Van Dijk, T.; Gerd Weitkamp, G. Quality over Quantity: Contribution of Urban Green Space to Neighborhood Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dillen, S.M.; De Vries, S.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green- space in urban neighbourhoods and residents’ health: Adding quality to quantity. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, G.R.; Rock, M.; Toohey, A.M.; Hignell, D. Characteristics of Urban Parks Associated with Park Use and Physical Activity: A Review of Qualitative Research. Health Place 2010, 16, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczynski, A.T.; Potwarka, L.R.; Saelens, B.E. Association of Park Size, Distance, and Features With Physical Activity in Neighborhood Parks. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownson, R.C.; Hoehner, C.M.; Day, K.; Forsyth, A.; Sallis, J.F. Measuring the Built Environment for Physical Activity: State of the Science. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, S99–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J.F. Measuring Physical Activity Environments: A Brief History. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, S86–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedimo-Rung, A.L.; Mowen, A.J.; Cohen, D.A. The Significance of Parks to Physical Activity and Public Health: A Conceptual Model. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpel, N.; Owen, N.; Leslie, E. Environmental factors associated with adults’ participation in physical activity: A review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikora, T.J.; Bull, F.C.L.; Jamrozik, K.; Knuiman, M.; Giles-Corti, B.; Donovan, R.J. Developing a Reliable Audit Instrument to Measure the Physical Environment for Physical Activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 23, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, B.E.; Lawrence, D.F.; Auffrey, C.; Whitaker, R.C.; Burdette, H.L.; Colabianchi, N. Measuring Physical Environments of parks and Playgrounds: EAPRS Instrument Development and Inter-rater Reliability. J. Phys. Health 2006, 3, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropped, P.J.; Cronley, E.K.; Fragala, M.S.; Melly, S.J.; Hasbrouck, H.H.; Gortmaker, S.L.; Brownson, R.C. Development and reliability and validity Testing of an Audit Tool for trail/path Characteristics: The Path Environment Audit Tool (PEAT). J. Phys. Act. Health 2006, 3, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place Standard. Place Standard- How Good Is Our Place. 2015. Available online: https://www.placestandard.scot/ (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- CABE. Spaceshaper- A User’s Guide. 2007. Available online: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/resources/guide/spaceshaper-users-guide (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Hamilton, K.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Fair, M.L.; Lévesque, L. Examining the Relationship between Park Neighborhoods, Features, Cleanliness, and Condition with Observed Weekday Park Usage and Physical Activity: A Case Study. J. Environ. Public Health 2017, 2017, 7582402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Mavoa, S.; Villanueva, K.; Sugiyama, T.; Badland, H.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Owen, N.; Giles-Corti, B. Public open space, physical activity, urban design and public health: Concepts, methods and research agenda. Health Place 2015, 33, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.F.; Christian, H.; Veitch, J.; Astell-Burt, T.; Hipp, J.A.; Schipperijn, J. The impact of interventions to promote physical activity in urban green space: A systematic review and recommendations for future research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 124, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, G.W.; Parra, D.C.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Andersen, L.B.; Owen, N.; Goenka, S.; Montes, F.; Brownson, R.C. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: Lessons from around the world. Lancet 2012, 380, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPAcE—Supporting Policy and Action for Active Environments. Environments for Physical Activity in Europe: A Review of Evidence and Examples of Practice, Erasmus+Programme of the European Union. 2017. Available online: http://activeenvironments.eu/ (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- NICE. Physical Activity and the Environment Update: Effectiveness and Cost Effectiveness Evidence Review 3: Park, Neighbourhood and Multicomponent Interventions, NICE Guideline NG90, Evidence Reviews, Ministers in the Welsh Government, Scottish Government, and Northern Ireland Executive; NICE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (Regional Office for Europe). Urban Green Space Interventions and Health: A Review of Impacts and Effectiveness; Full Report; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, B.W.; Lovell, R.; Higgins, S.L.; White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Osborne, N.J.; Husk, K.; Sabel, C.E.; Depledge, M.H. Beyond greenspace: An ecological study of population general health and indicators of natural environment type and quality. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2015, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, M. Paracity: Urban Acupuncture. In Proceedings of the Public Spaces Bratislava, Bratislava, Slovakia, 20 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande, M. Urban Acupuncture. 2019. Available online: http://helsinkiacupuncture.blogspot.com/2008/12/blog-post.html (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Lerner, J. Urban Acupuncture; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Sola Morales, M. A Matter of Things; Nai Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Unt, A.L.; Bell, S. The impact of small-scale design interventions on the behaviour patterns of the users of an urban wasteland. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosco, N.G.; Moore, R.C.; Islam, M.Z. Behavior Mapping: A Method for Linking Preschool Physical Activity and Outdoor Design. Off. J. Am. Coll. Sports Med. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward Thompson, C. Activity, exercise and the planning and design of outdoor spaces. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, H. Affordances and the perception of landscape: An inquiry into environmental perception and aesthetics, Affordances in the landscape: A theoretical approach. In Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space 2; Catharine Ward, T., Peter, A., Simon, B., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hartson, R. Cognitive, physical, sensory, and functional affordances in interaction design. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2003, 22, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essex, S.J.; Ford, P. Urban regeneration: Thirty years of change on Plymouth’s waterfront. Trans. Devon. Assoc. 2015, 147, 73–102. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.; Goss, Z.; Pratt, A.; Sharman, J.; Tighe, M. Building HIA approaches into strategies for green space use: An example from Plymouth’s (UK) Stepping Stones to Nature project. Health Promot. Int. 2013, 28, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Denford, S.; Smith, J.; Dean, S.; Greaves, C.; Lloyd, J.J.; Tarrant, M.; White, M.P.; Wyatt, K. Designing, Implementing and Evaluating Interventions to Change Health-Related Behaviour, Chp 3. In Complex Interventions in Health: An Introduction to Research Methods; Richards, D.A., Rahm Hallberg, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, E.; Kindermann, G.; Domegan, C.; Carlin, C. Blue care: A systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 35, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, H.S.; Bell, S.; Vassiljev, P.; Kuhlmann, F.; Niin, G.; Grellier, J. The development of a tool for assessing the environmental qualities of urban blue spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goličnik, B.; Ward Thompson, C. Emerging relationships between design and use of urban park spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, T.L.; Cohen, D.A.; Sehgal, A.; Williamson, S.; Golinelli, D. System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC): Reliability and Feasibility Measures. J. Phys. Act. Health 2006, 3, S208–S222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Grellier, J.; Wheeler, B.W.; Hartig, T.; Warber, S.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E.F. 120 minutes of nature contact per week is positively related to health and wellbeing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, J.; White, M.P.; Huang, J.; Ng, S.; Hui, Z.; Leung, C.; Tse, S.; Fung, F.; Elliott, L.R.; Depledge, M.H.; et al. The association between blue space exposure, health and wellbeing in Hong Kong. Health Place 2019, 55, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grellier, J.; White, M.P.; Albin, M.; Bell, S.; Elliott, L.R.; Gascón, M.; Gualdi, S.; Mancini, L.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Sarigiannis, D.A.; et al. BlueHealth: A study programme protocol for mapping and quantifying the potential benefits to public health and well-being from Europe’s blue spaces. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.T. Contingent Valuation: A Comprehensive Bibliography and History; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, D.; Campbell, R. Valuation Techniques for Social Cost-Benefit Analysis: Valuation Techniques for Social Cost-Benefit Analysis, A Discussion of the Current Issues; HM Treasury: London, UK, 2011.

- HM Treasury. The Green Book: Appraisal and Evaluation in Central Government, The Green Book; HM Treasury and the Department for Work & Pensions: London, UK, 2018.

- Bateman, I.J.; Carson, R.T.; Day, B.; Hanemann, M.; Hanley, N.; Hett, T.; Jones-Lee, M.; Loomes, G.; Mourato, S.; Özdemirog-lu, E.; et al. Economic Valuation with Stated Preference Techniques: A Manual; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, R.; Hanneman, W.M. Contingent valuation. In Handbook of Environmental Economics; Mäler, K.G., Vincent, J.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.; Carson, R. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method; Resources for the Future: Washington DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Haab, T.C.; McConnell, K.E. Valuing Environmental and Natural Resources. In The Econometrics of Non-Market Valuation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, N.; Shogren, J.; White, B. Environmental Economics: In Theory & Practice, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R.J.; Boyle, K.J.; Adamowicz, W.; Bennett, J.; Brouwer, R.; Cameron, T.A.; Hanemann, W.M.; Hanley, N.; Ryan, M.; Scarpa, R.; et al. Contemporary guidance for stated preference studies. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, M.A.; Depledge, M.H. Healthy people with nature in mind. BMC Public Health 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.F.; Cleland, C.; Cleary, A.; Droomers, M.; Wheeler, B.W.; Sinnett, D.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Braubach, M. Environmental, heal. lth, wellbeing, social and equity effects of urban green space interventions: A meta-narrative evidence synthesis. Environ. Int. 2019, 130, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vert, C.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Gascon, M.; Grellier, J.; Fleming, L.E.; White, M.P.; Rojas-Rueda, D. Health risk assessment of community riverside regeneration in Barcelona. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 01. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.P.; Elliott, L.R.; Taylor, T.; Wheeler, B.W.; Spencer, A.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E. Recreational physical activity in natural environments and implications for health: A population based cross-sectional study in England. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, L.R.; White, M.P.; Grellier, J.; Rees, S.E.; Waters, R.D.; Fleming, L.E. Recreational visits to marine and coastal environments in England: Where, what, who, why, and when? Mar. Policy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Phoenix, C.; Lovell, R.; Wheeler, B.W. Seeking everyday wellbeing: The coast as a therapeutic landscape. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 142, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Wheeler, B.W.; Phoenix, C. Using Geonarratives to Explore the Diverse Temporalities of Therapeutic Landscapes: Perspectives from “Green” and “Blue” Settings. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, R. Swimming as an accretive practice in healthy blue space. Emot. Space Soc. 2017, 22, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.R.; Richardson, E.A.; Mitchell, R.J.; Shortt, N.K. Environmental justice and health: The implications of the socio-spatial distribution of multiple environmental deprivation for health inequalities in the United Kingdom. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2010, 35, 522–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.; Pugach, O.; Lin, W.; Bontu, A. If You Build It Will They Come? Does Involving Community Groups in Playground Renovations Affect Park Utilization and Physical Activity? Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzini, L.; Taylor, W.; Elliott, M.N.; Cuccaro, P.; Tortolero, S.R.; Janice Gilliland, M.; Grunbaum, J.A.; Schuster, M.A. Neighborhood characteristics favorable to outdoor physical activity: Disparities by socioeconomic and racial/ethnic composition. Health Place 2010, 16, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faehnle, M.; Bäcklundb, P.; Tyrväinenc, L.; Niemelä, J.; Yli-Pelkonend, V. How can residents’ experiences inform planning of urban green infrastructure? Case Finl. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 130, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Renovation Element | Example of Functional and Cognitive Affordances |

|---|---|

| Open-air theatre (circular floor/stage, wall, hard stepped seating, grass area on slope for seating) | The circular floor/stage (or “orchestra” in ancient Greek theatre terms) allows people to gather, stand, sit, view, engage in social interactions, play with dogs, relax and observe. The flat surface allows wheelchair users to sit and observe and stay close to the water. The wall around the stage allows people to lean-on to and sit on it. Seating areas (i.e., hard and soft) allow people to sit and lounge freely, sunbathe, view, exercise, read and sit to eat and drink. |

| Slipway resurfacing improvement | To improve perceived physical safety and allow people to go closer to the water. |

| Vegetation clearance (along the edge and face of the cliff) | To open up views, increase visibility and improve perceived safety and place attractiveness. |

| Children’s play area improvement (new play surface, sand pit, new play units) | To increase place attractiveness, safety and encourage play activity. |

| Installation of information boards | To enhance knowledge about the biodiversity, environmental quality of the site and history of the area, in addition to activities and project related information. |

| Installation of gates | To improve pedestrian accessibility, prevent parking (negative affordance), facilitate easy access to children’s play area and prevent dogs accessing the area (negative affordance). |

| Behaviour Change Technique Category | Behaviour Change Technique | Operationalisation |

|---|---|---|

| Social support | Social support (practical) | Formal organisation of public “fun” days at Teats Hill where other people from the local community would also be present. Promoted to the community though flyers around the community and leaflet drops. |

| Shaping knowledge | Instruction on how to perform a behaviour | New signage provided instruction on how to carry out recreational activities in an environmentally responsible way. For example, while rock-pooling, “Use a bucket to scoop up creatures – nets can cause injury and pull up seaweed”. At public engagement days, activity facilitators often instructed attendees on how to perform certain behaviours in a safe and ecologically sensitive way such as litter picking. |

| Natural consequences | Information about social and environmental consequences | Operationalised in a number of ways on new Teats Hill signage. For example, opportunities to enjoy the views, the wildlife, to connect with the site’s history, its flora, its new facilities, and the new artificial habitats (bio-blocks). |

| Natural consequences | Salience of consequences (i.e., to make above consequences more memorable) | On the signage, people were invited to share photographs of the improved views or of wildlife on social media. Contact details of how to book the new facilities (e.g., open air theatre) were provided. People were invited to count how many marine animal species they could identify, and how species of seaweed they could find. People were encouraged to “look out” for particular plants (ox-eye daisy, vipers bugloss). |

| Comparison of behaviour | Demonstration of behaviour | Activity facilitators attending public engagement events at Teats Hill would often demonstrate environmentally responsible behaviours (litter-picking, sustainable rock-pooling) in order to inform visitors on how to conduct these activities safely and in an ecologically responsible manner. |

| Associations | Prompts/cues | New signage prompted specific environmental behaviours upon entering the site. For example, “always put rock pool creatures back where you find them,” or, “only keep one creature in your bucket at a time,” or “help us care for this beach by taking your litter home”. |

| Comparison of outcomes | Comparative imagining of future outcomes | The public engagement process allowed both the imagining of future recreational visits to the site and what these would involve post-renovation, and the opportunity for school children to imagine the future of the site in a virtual world of “Minecraft” and thus how it may attract or support recreation. |

| Reward and threat | Material incentive | Adverts for public engagement days (“fun days”) often included material incentives. For example, pasties, hot drinks, and family games were offered as incentives for visiting the site on these specific public engagement days. New signage also offered the incentive of enjoying the nearby aquarium before or after a visit. |

| Reward and threat | Material reward | Attendees who visited the site on public engagement days (“fun day”) were often, in addition to the above, offered rewards for doing so that they may previously have been unaware of. These ranged from food and drink, to the opportunity to participate in voluntary social or environmental activities. |

| Antecedents | Restructuring the physical environment | Certain elements of the site were restructured e.g., the removal of overgrown vegetation and litter which had previously obstructed views, and removal of illegally parked cars from the slipway. These strategies were aimed at increasing recreation. |

| Antecedents | Restructuring the social environment | Often, public engagement events were specifically aimed at families i.e., they advised that people visit with their family in an effort to increase recreational visits. |

| Antecedents | Adding objects to the environment | The addition of the new play equipment, open air theatre, and signage represented the principal additions to the environment which were used to encourage increased recreational behaviour. |

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| Part 1: Green and blue spaces | Questions concerning frequency of visits to green and blue spaces in general. Questions concerning details of most recent visit to Teats Hill, including activities, duration, companions etc. |

| Part 2: Perceptions of Teats Hill | Perceived environmental quality, safety, community engagement etc. |

| Part 3: Economic valuation | (i) Before survey—How much would respondents be willing-to-pay (WTP) for the proposed improvements (ii) After survey—How much would respondents be willing-to-pay (WTP) for site maintenance |

| Part 4: Background information | Questions concerning the respondent’s health and well-being and socio-demographics. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bell, S.; Mishra, H.S.; Elliott, L.R.; Shellock, R.; Vassiljev, P.; Porter, M.; Sydenham, Z.; White, M.P. Urban Blue Acupuncture: A Protocol for Evaluating a Complex Landscape Design Intervention to Improve Health and Wellbeing in a Coastal Community. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4084. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104084

Bell S, Mishra HS, Elliott LR, Shellock R, Vassiljev P, Porter M, Sydenham Z, White MP. Urban Blue Acupuncture: A Protocol for Evaluating a Complex Landscape Design Intervention to Improve Health and Wellbeing in a Coastal Community. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4084. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104084

Chicago/Turabian StyleBell, Simon, Himansu Sekhar Mishra, Lewis R. Elliott, Rebecca Shellock, Peeter Vassiljev, Miriam Porter, Zoe Sydenham, and Mathew P. White. 2020. "Urban Blue Acupuncture: A Protocol for Evaluating a Complex Landscape Design Intervention to Improve Health and Wellbeing in a Coastal Community" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4084. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104084

APA StyleBell, S., Mishra, H. S., Elliott, L. R., Shellock, R., Vassiljev, P., Porter, M., Sydenham, Z., & White, M. P. (2020). Urban Blue Acupuncture: A Protocol for Evaluating a Complex Landscape Design Intervention to Improve Health and Wellbeing in a Coastal Community. Sustainability, 12(10), 4084. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104084