Corporate Social Performance: An Assessment Model on an Emerging Market

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. CSR and CSP

2.2. CSR in Emerging Markets

2.3. Romania: the Research Context

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Research Approach Steps

3.3. Sample Description

4. Results

4.1. Model Consistency

- -

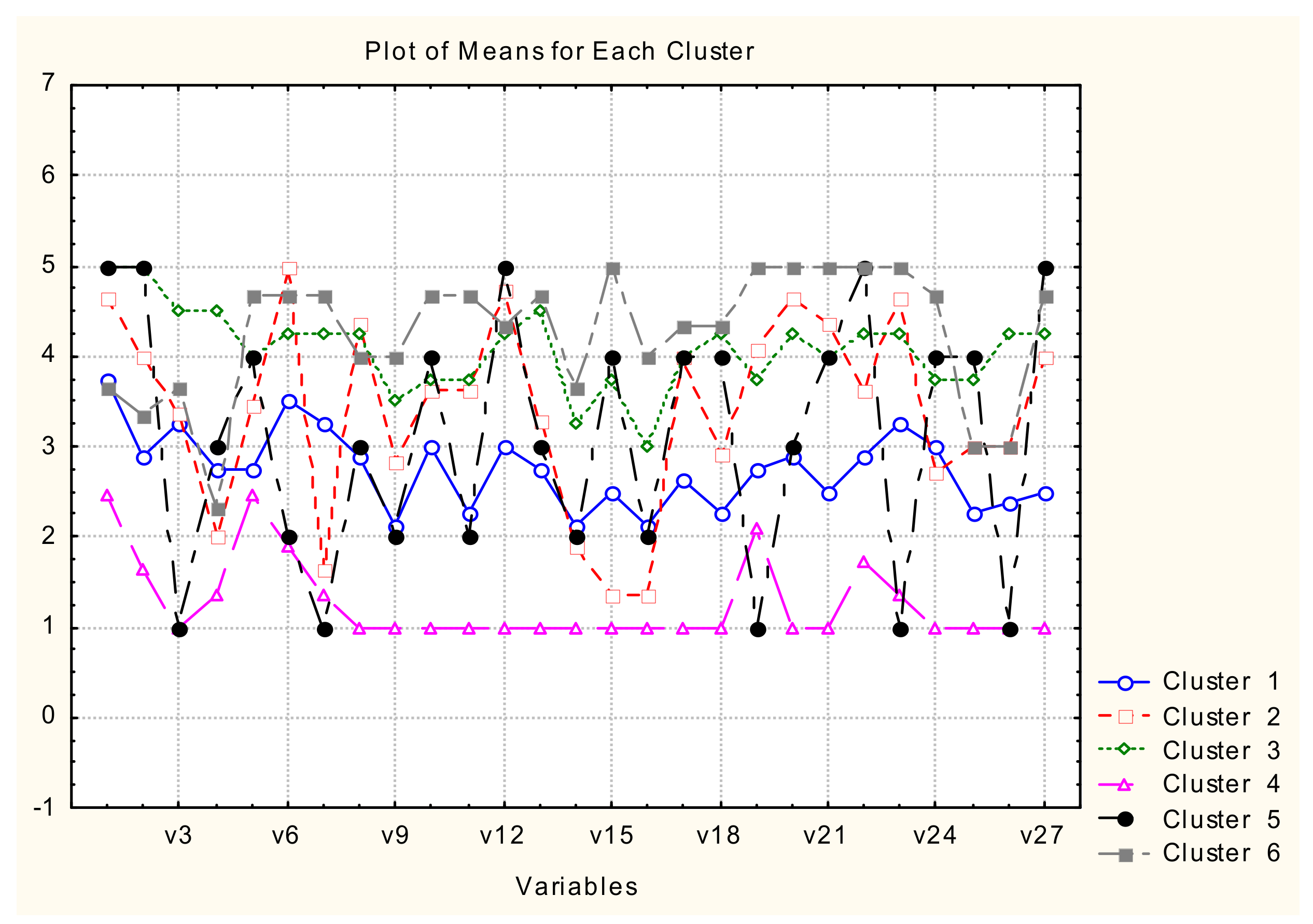

- Groups 1, 2, 5 and 6 are correlated with the “degree of internationalization” of the company;

- -

- Groups 2 and 3 are correlated with the “consumer education process promoted by the company”;

- -

- Groups 1, 2 and 3 are correlated with “fraud and false advertising”;

- -

- Group 1 and 4 are correlated with “past anti-corruption/bribery policies”;

- -

- Groups 2, 4, 5 and 6 are correlated with the “reporting method used for CSP”;

- -

- Groups 1, 3 and 4 are correlated with “board independence”.

4.2. Description of the Identified Typologies/Clusters

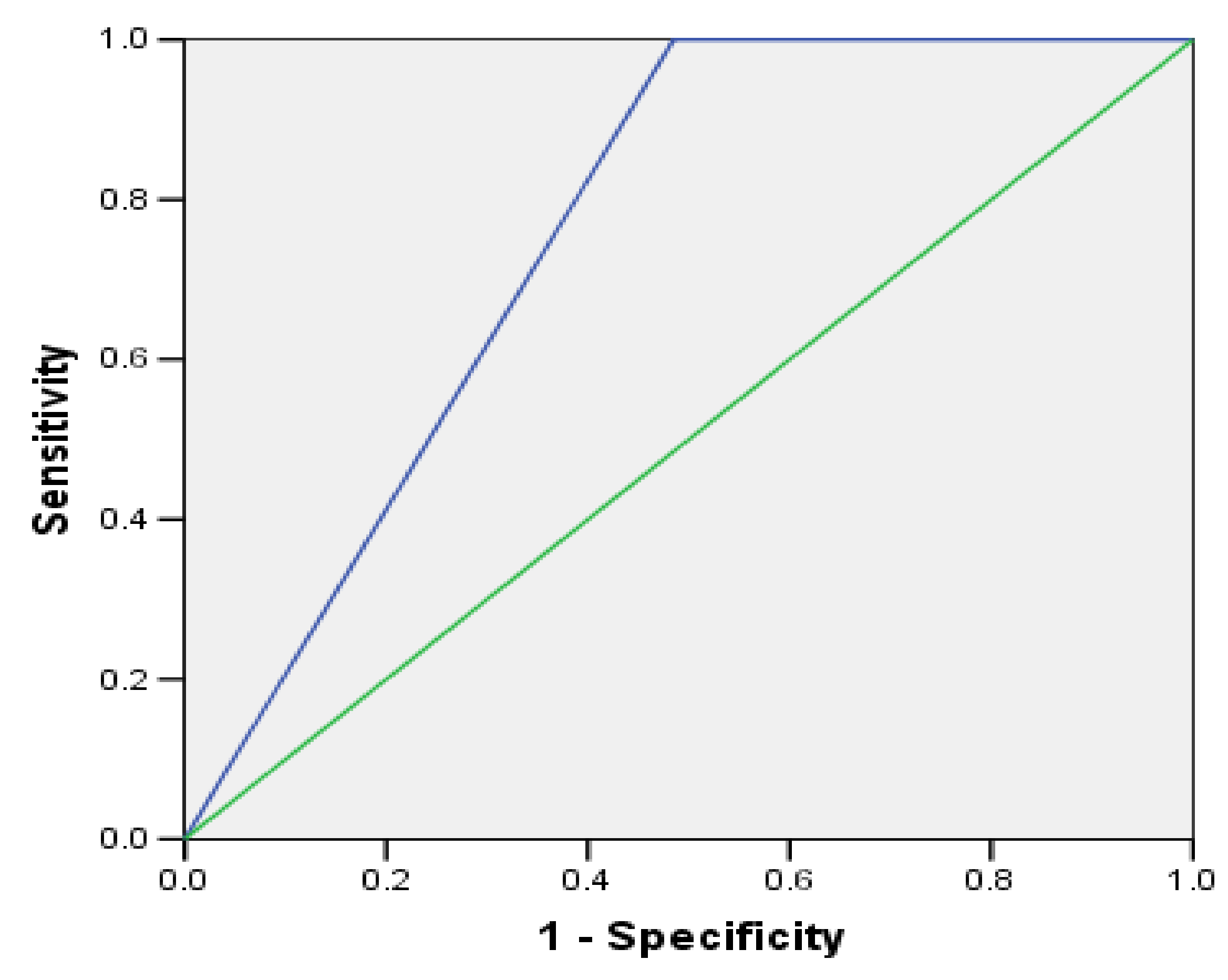

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Scale Mean if Item Deleted | Scale Variance if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Interpretation of Discrimination Item | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | KMO > 0.7 | Cluster Analysis Variance Analyses - F test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Companies’ image and reputation in the market | 81.96 | 562.230 | 0.659 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.720 | F = 18.028 ** |

| Market presence | 82.43 | 557.956 | 0.656 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.873 | F = 48.039 ** |

| Economic performance | 82.66 | 558.324 | 0.643 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.826 | F = 41.828 ** |

| Return of socially responsible investments | 83.08 | 573.590 | 0.398 | gi | 0.963 | 0.915 | F = 26.658 ** |

| Procurement practices | 82.60 | 554.511 | 0.827 | vgi | 0.960 | 0.750 | F = 14.694 ** |

| Social practices | 82.16 | 556.256 | 0.661 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.771 | F = 25.176 ** |

| The degree of companies’ internationalization | 82.75 | 558.460 | 0.579 | vgi | 0.962 | 0.858 | F = 49.335 ** |

| Consumer education process promoted by the company | 82.58 | 550.735 | 0.743 | vgi | 0.960 | 0.730 | F = 27.158 ** |

| Fraud and false advertising | 83.27 | 552.807 | 0.711 | vgi | 0.960 | 0.726 | F = 16.598 ** |

| Supplier environmental assessment | 82.58 | 554.052 | 0.666 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.921 | F = 19.866 ** |

| The use of eco labels (e.g., Fair Trade) | 82.96 | 546.718 | 0.810 | vgi | 0.960 | 0.780 | F = 48.637 ** |

| Certification schemes | 82.34 | 553.934 | 0.663 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.844 | F = 39.995 ** |

| Environmental grievance mechanisms | 82.63 | 546.139 | 0.827 | vgi | 0.959 | 0.884 | F = 46.454 ** |

| The degree to which employees are involved in the available forms of participation in profits | 83.48 | 563.619 | 0.601 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.666 | F = 16.554 ** |

| Customer pressure on environment and social protection | 83.02 | 550.780 | 0.638 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.837 | F = 41.678 ** |

| Governmental/NGO pressure | 83.55 | 563.006 | 0.650 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.882 | F = 38.392** |

| Shareholder satisfaction towards social impact of CSR policies | 82.67 | 553.051 | 0.672 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.819 | F = 23.908 ** |

| Codes of ethics compliance | 82.92 | 546.859 | 0.731 | vgi | 0.960 | 0.793 | F = 26.882 ** |

| Motivating and retaining talented employees | 82.57 | 560.297 | 0.599 | gi | 0.961 | 0.772 | F = 26.722 ** |

| Equal remuneration for women and men | 82.40 | 543.681 | 0.772 | vgi | 0.960 | 0.923 | F = 36.991 ** |

| Past anti-corruption/bribery policies | 82.58 | 543.515 | 0.818 | vgi | 0.959 | 0.919 | F = 21.949 ** |

| Business partners’ human rights assessment | 82.34 | 556.373 | 0.642 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.852 | F = 67.741 ** |

| Industry trends regarding sustainable development | 82.30 | 553.798 | 0.692 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.910 | F = 90.603 ** |

| External economic conditions | 82.70 | 557.603 | 0.781 | vgi | 0.960 | 0.792 | F = 21.073 ** |

| Committees, forums, panels, departments, etc. involved in CSR | 83.19 | 563.718 | 0.608 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.896 | F = 32.766 ** |

| Reporting method used for CSR performance | 83.19 | 558.938 | 0.649 | vgi | 0.961 | 0.909 | F = 98.158 ** |

| Board independence | 82.58 | 545.466 | 0.786 | vgi | 0.960 | 0.904 | F = 56.158 ** |

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between People | 1815.231 | 82 | 22.137 | |||

| Within People | Between Items | 333.637 | 26 | 12.832 | 15.282 | 0.000 |

| Residual | 1790.215 | 2132 | 0.840 | |||

| Total | 2123.852 | 2158 | 0.984 | |||

| Total | 3939.083 | 2240 | 1.759 | |||

| Item | Chi-Square (a,b) | df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Companies’ image and reputation in the market | 45.011 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Market presence | 16.046 | 4 | 0.003 |

| Economic performance | 15.126 | 4 | 0.004 |

| Return of socially responsible investments | 9.609 | 4 | 0.048 |

| Procurement practices | 19.724 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Social practices | 25.241 | 4 | 0.000 |

| The degree of companies’ internationalization | 5.647 | 4 | 0.227 |

| Consumer education process promoted by the company | 36.706 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Fraud and false advertising | 19.529 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Supplier environmental assessment | 15.059 | 4 | 0.005 |

| The use of eco labels (e.g., Fair Trade) | 10.824 | 4 | 0.029 |

| Certification schemes | 11.765 | 4 | 0.019 |

| Environmental grievance mechanisms | 6.588 | 4 | 0.159 |

| The degree to which employees are involved in the available forms of participation in profits | 20.235 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Customer pressure on environment and social protection | 5.412 | 4 | 0.248 |

| Governmental/NGO pressure | 37.412 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Shareholder satisfaction towards social impact of CSR policies | 26.824 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Codes of ethics compliance | 2.353 | 4 | 0.671 |

| Motivating and retaining talented employees | 10.824 | 4 | 0.029 |

| Equal remuneration for women and men | 18.824 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Past anti-corruption/bribery policies | 4.706 | 4 | 0.03 |

| Business partners’ human rights assessment | 16.471 | 4 | 0.002 |

| Industry trends regarding sustainable development | 14.588 | 4 | 0.006 |

| External economic conditions | 37.647 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Committees, forums, panels, departments, etc. involved in CSR | 21.647 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Reporting method used for CSR performance | 12.706 | 4 | 0.013 |

| Board independence | 4.706 | 4 | 0.04 |

References

- Dobers, P.; Halme, M. Corporate social responsibility and developing countries. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.L.; Tan, W.; Ahn, H.J.; Zhang, Z. Does corporate social responsibility matter Asian emerging markets. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Thomsen, P.; Lindgreen, A.; Vanhamme, J. Industrial clusters and corporate social responsibility in developing countries: What we know, what we do not know, and what we need to know. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure in Developed and Developing Countries: A Literature Review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, I.D.; Dabija, D.C. ISO 26000—A Brief Literature Review. In ISO 26000—A Standardized View on Corporate Social Responsibility; Idowu, S.O., Sitnikov, C., Simion, D., Bocean, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A company-level measurement approach for CSR. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesterházy, Á.; Oláh, J.; Popp, J. Losses in the Grain Supply Chain: Causes and Solutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crişan-Mitra, C.; Borza, A. Approaching CSR in Romania: An empirical Analysis. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Welford, R.; Frost, S. Corporate social responsibility in Asian supply chains. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. The case for strategic corporate social responsibility in developing countries. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2007, 112, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Wang, D.Y.; Jiang, Y. An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.U.; Rasche, A.; Waddock, S. Accountability in a global economy: The emergence of international accountability standards. Bus. Ethics Q. 2011, 21, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, F.J.; García-Rodríguez, J.L.; Castilla-Gutiérrez, C.; Major, S.A. Corporate social responsibility of oil companies in developing countries: From altruism to business strategy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, E. Human rights and corporate social responsibility in developing countries’ industrial clusters. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, I.W.K.; Azizan, N.A.; Bhaskaran, R.K.; Sukumaran, S.K. Corporate Social Performance and Firm Performance: Comparative Study among Developed and Emerging Market Firms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.R.; Eden, L.; Li, D. CSR Reputation and Firm Performance: A Dynamic Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 163, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pozo, A.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Sánchez-Ollero, J.L. Internet’s User Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility in Hotel Services. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Minor, D.B.; Wang, J.; Yu, C. A Learning Curve of the Market: Chasing Alpha of Socially Responsible Firms. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2019, 109, 103772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, A.; Li, Z.F.; Minor, D. CSR-Contingent Executive Compensation Contracts. J. Bank. Finance 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, E.; Willems, M.; Lapointe, M.; Makarenkov, V. Using the stability of objects to determine the number of clusters in datasets. Inf. Sci. 2017, 393, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkin, B. Core Data Analysis: Summarization, Correlation, and Visualization, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 54, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lakner, Z.; Kiss, A.; Popp, J.; Zéman, Z.; Máté, D.; Oláh, J. From Basic Research to Competitiveness: An Econometric Analysis of the Global Pharmaceutical Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuli, A.; Kostovetsky, L. Are red or blue companies more likely to go green? Politics and corporate social responsibility. J. Financ. Econ. 2014, 111, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Lines of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, W.; Schapper, J. Two approaches to curriculum development for educating for sustainability and CSR. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.C.; Băbuţ, R. Empirical Study on the Impact of Service, Communication and Corporate Social Responsability on the Image of Romanian Retail Brands. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, H.; Raithel, S.; Zheng, Q. Corporate social performance, analyst stock recommendations, and firm future returns. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, R.; Hall, A.D.; Momente, F.; Reggiani, F. What corporate social responsibility activities are valued by the market? J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility a review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility Is to Increase Its Profits. New York Times Mag. 1970, 13 September, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, J.B.; Sundgren, A.; Schneeweis, T. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 854–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi-Belkaoui, A. Executive compensation, organisational effectiveness, social performance and firm performance: An empirical investigation. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 1992, 19, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, A. The limits of corporate responsibility standards. Bus. Ethics: A Eur. Rev. 2010, 12, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, K.E.; Van Pham, D. An Expanded Investigation in the Relationship Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 2, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.A.; Lenox, M.J. Industry self-regulation without sanctions: The chemical industry’s responsible care program. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kwanglim, S.; Amit, S. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the airline industry: The moderating role of oil prices. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, W.; Vveinhardt, J. Nepotism and favouritism in the steel industry: A case study analysis. Forum Sci. Oeconomia 2018, 6, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D. Corporate social performance revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbeleke, A.A. Strategic corporate responsibility and sustainability performance management model. J. Manag. Sustain. 2014, 4, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Colle, S. CSR and management systems. In Corporate Social Responsibility: Concepts, Accountability and Reporting; Alluche, J., Ed.; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 333–353. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Zanhour, M.; Keshishian, T. Peculiar strengths and relational attributes of SMEs in the context of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.C.; Bejan, B.M. Sustainability reporting of grocery retailers on an emerging market. In New Trends in Sustainable Business and Consumption. In Proceedings of the 4th BASIQ International Conference, Heidelberg, Germany, 11–13 June 2018; Pleșea, D., Vasiliu, C., Murswieck, A., Pamfilie, R., Dinu, V., Tăchiciu, L., Olaru, M., Eds.; Editura ASE: Bucharest, Romania, 2018; pp. 611–619. [Google Scholar]

- Vveinhardt, J.; Andriukaitiene, R. Management Culture as Part of Organizational Culture in the Context of Corporate Social Responsibility Implementation. Econ. Sociol. 2017, 10, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfman, M. The construct validity of the Kinder, Lydenberg and Domini social performance ratings data. J. Bus. Ethics 1996, 15, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Walsh, J.P. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.T. The advertising effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and brand equity: Evidence from the life insurance industry in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remišová, A.; Búciová, Z. Measuring corporate social responsibility towards employees. J. East. Eur. Manag. Stud. 2012, 17, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryzel, B.; Seppala, N. The effect of CSR evaluations on affective attachment to CSR in different identity orientation firms. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; Shang, J. How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. Acad. Mark. Sci. J. 2011, 39, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreck, P. Reviewing the business case for corporate social responsibility: New evidence and analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Corporate Social Responsibility: Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament the Council. 2011. The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the regions. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52011DC0681Brussels (accessed on 25 May 2012).

- Corporate Citizenship. Inclusive Business-The Next Frontier for Corporate Responsibility; Corporate Citizenship: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; He, Y.; Lin, W.; Streimikis, J. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility with Reputation and Brand of the Firm. Amfiteatru Econ. 2019, 21, 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiatkiewicz, O. Market Communication: Ethical and Praxeological Dimensions. Econ. Sociol. 2018, 11, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taran, Z.; Mirkin, B. Exploring patterns of corporate social responsibility using a complementary K-means clustering criterion. Bus. Res. 2020, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőrinczy, M.; Sroka, W. Theoretical assumptions of the ethical business model. In New Approaches and Tendencies in Entrepreneurial Management. International Conference Proceedings; Nicolescu, O., Plesoianu, G., Costin-Cirstea, A., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 198–215. [Google Scholar]

- Papasolomou-Doukakis, I.; Krambia-Kapardis, M.; Katsioloudes, M. Corporate social responsibility: The way forward? Maybe not! A preliminary study in Cyprus. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2005, 17, 27–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vătămănescu, E.M.; Gazzola, P.; Dincă, V.M.; Pezzetti, R. Mapping Entrepreneurs’ Orientation towards Sustainability in Interaction versus Network Marketing Practices. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Vatamanescu, E.M.; Andrei, A.G.; Marrapodi, C. Users’ motivations to participate in the sharing economy: Moving from profits toward sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küskü, F. From necessity to responsibility: Evidence for corporate environmental citizenship activities from a developing country perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2007, 14, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.; Kuznetsova, O.; Warren, R. CSR and legitimacy of business in transition economies: The case of Russia. Scand. J. Manag. 2009, 25, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan-Mitra, C.; Dinu, V.; Postelnicu, C.; Dabija, D.C. Corporate Practice of Sustainable Development on an Emerging Market. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2016, 15, 228–243. [Google Scholar]

- Androniceanu, A. Social Responsibility, an Essential Strategic Option for a Sustainable Development in the Field of Bio-Economy. Amfiteatru Econ. 2019, 21, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özen, Ş.; Küskü, F. Corporate environmental citizenship variation in developing countries: An institutional framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdora-Aksak, E.; Atakan-Duman, S. Gaining legitimacy through CSR: An analysis of Turkey’s 30 largest corporations. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiron-Tudor, A.; Nistor, C.S.; Ștefănescu, C.A.; Zanellato, G. Encompassing Non-Financial Reporting in A Coercive Framework for Enhancing Social Responsibility: Romanian Listed Companies’ Case. Amfiteatru Econ. 2019, 21, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Fotiadis, T.A.; Christodoulides, P. Antecedents and consequences of an eco-friendly export marketing strategy: The moderating role of foreign public concern and competitive intensity. J. Int. Mark. 2013, 21, 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idemudia, U. Corporate social responsibility and developing countries: Moving the critical CSR research agenda in Africa forward. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2011, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chedrawi, C.; Osta, A.; Osta, S. CSR in the Lebanese banking sector: A neo-institutional approach to stakeholders’ legitimacy. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.C.; Băbuț, R. Enhancing Apparel Store Patronage through Retailers’ Attributes and Sustainability. A Generational Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obucina, V. Romania Shows Fast Economic Growth after 10 Years in the EU. 2020. Available online: https://financialobserver.eu/cse-and-cis/romania/romania-shows-fast-economic-growth-after-10-yearsin-eu (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Speed Test. 2020. Available online: https://www.speedtest.net/global-index (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- EIR. The Environmental Implementation Review 2019. Country Report Romania 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eir/pdf/report_ro_en.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Dabija, D.C.; Bejan, B.; Tipi, N. Generation X versus Millennials Communication Behavior on Social Media when Purchasing Food versus Tourist Services. Econ. Manag. 2018, 21, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan-Mitra, C.; Borza, A. Social entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibilities. Int. Bus. Res. 2012, 5, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idemudia, U.; Kwakyewah, C. Analysis of the Canadian national corporate social responsibility strategy: Insights and implications. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbeleke, A.A. From Carroll’s Pyramid to Elkington TBL: A Move towards Integrated Impact Assessment Driven Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability Performance Reporting System. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2013, 3, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- De Colle, S.; Henriques, A.; Sarasvathy, S. The paradox of corporate social responsibility standards. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobal Reporting Initiative. 2015. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/GRIG4-Part1-Reporting-Principles-and-Standard-Disclosures.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2015).

- Hutton, J.G.; Goodman, M.B.; Alexander, J.B.; Genest, C.M. Reputation management: The new face of corporate public relations? Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 27, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan-Mitra, C.; Dabija, D.C.; Dinu, V. Social Entrepreneurship in Romania: Significance and Models. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2015, 11, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A. SWOT does not need to be recalled: It needs to be enhanced. Swineburne Res. Bank 2000, 14, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, A. SWOT Analysis for Management Consulting; SRI Alumni Newsletter; SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ListaFirme.ro. 2018. List of Romanian Companies. Available online: https://www.listafirme.ro/stare-firme.asp?gclid=CjwKCAjw4871BRAjEiwAbxXi2zGS38VxHFGdXbbgdES7WYyvZd44zjfI5zZEy199EhLifHIlpNsI7BoCYX0QAvD_BwE (accessed on 12 February 2018).

- Law no. 346/2004. Available online: http://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/53946 (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Statistical Yearbook, 2019. Statistical Yearbook of Romania for 2019. Available online: http://www.insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/anuarul_statistic_al_romaniei_carte_ro.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2019).

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Enachescu, D. Data Maining, Metode si Aplicatii; Editura Academiei Române: Bucharest, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Culic, I. Metode Avansate în Cercetarea Social—Analiza Multivariată de Interdependență; Polirom: Iași, Romania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Drugan, T.; Achimas, A.; Tigan, S. Biostatistics; SRIMA: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.P.; Shaver, P.R.; Wrightsman, L.S. Criteria for scale selection and evaluation. In Measures of Social Psychological Attitudes; Robinson, J.P., Shaver, P.R., Wrightsman, L.S., Eds.; San Diego Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, M. Statistica pentru psihologi. Teorie și aplicații SPSS; Colecția Collegium, Psihologie; Polirom: Bucuresti, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Opariuc, C.D. Analiza Componentelor Principale pentru date Categoriale (CATPCA). 2012. Available online: rpru.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/vol10_2_2012.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Ralambondrainy, H. A conceptual version of the k-means algorithm. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 1995, 16, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoş, C.M. ROC curve for discrete choice models an application to the Romanian car market. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2010, 17, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, J.L.; Levin, B.; Paik, M.C. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, G.; Stokes, M. Reliability of assessment tools in rehabilitation: An illustration of appropriate statistical analyses. Clin. Rehabil. 1998, 12, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimonenko, T.; Bilan, Y.; Horák, J.; Starchenko, L.; Gajda, W. Green Brand of Companies and Greenwashing under Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, R.L.; Starbuck, W.H. Learning to design organizations and learning from designing them. Organ. Sci. 2006, 17, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Howard-Grenville, J.; Joshi, A.; Tihanyi, L. Understanding and tackling societal grand challenges through management research. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1880–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F. An Empirical Assessment of Empirical Corporate Finance. SSRN J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F. Managerial Attributes, Incentives, and Performance. Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelling, E.; Webb, E. Corporate social Responsibility and financial performance: The “virtuous circle” revisited. Rev. Quant. Finan Acc. 2009, 32, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.; Li, Z.F.; Minor, D. Corporate Governance and Executive Compensation for Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.C.T. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and sustainable financial performance: Firm-level evidence from Taiwan. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Thibodeau, C. CSR-Contingent Executive Compensation Incentive and Earnings Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Neville, B. Convergence versus divergence of CSR in developing countries: An embedded multi-layered institutional lens. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators/factors | Loading | EV % | Rotation Method: Varimax % of Var. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procurement practices | 0.650 | 52.53% | 20.20% |

| Degree to which employees are involved in the available forms of participation in profits | 0.666 | ||

| The pressure of clients regarding social and environmental protection | 0.853 | ||

| Governmental/NGO pressure | 0.882 | ||

| Training programs on codes of ethics for employees | 0.793 | ||

| Past anti-corruption/bribery policies | 0.919 | ||

| External economic conditions | 0.793 | ||

| Economic performance (e.g., turnover, profitability, level of indebtedness) | 0.826 | 8.52% | 17.567% |

| Social practices (company’s contributions to the local community, community rights, jobs creation, etc.) | 0.771 | ||

| The degree of companies’ internationalization | 0.858 | ||

| Fraud and false advertising | 0.726 | ||

| The use of eco labels (e.g., Fair Trade) | 0.780 | ||

| Motivating and retaining talented employees | 0.772 | ||

| Industry trend regarding sustainable development | 0.910 | ||

| Companies’ image and reputation in the market | 0.720 | 6.76% | 16.854% |

| Market presence (e.g., market share, sales gained in the social campaign) | 0.873 | ||

| Consumer education process promoted by the company | 0.730 | ||

| Certification schemes | 0.844 | ||

| Declaring harmful effects on the environment | 0.884 | ||

| Equal remuneration for women and men | 0.923 | 6.39% | 11.885% |

| Committees, forums, panels, departments, etc. involved in CSR | 0.893 | ||

| Reporting method used for CSP (format and verification) | 0.909 | ||

| Supplier environmental assessment | 0.921 | 4.95% | 9.208% |

| Shareholders’ satisfaction regarding the social impact of CSR | 0.819 | ||

| Business partners human rights assessment | 0.852 | ||

| Board independence | 0.904 | 3.71% | 7.127%, |

| Return of socially responsible investments | 0.915 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crișan-Mitra, C.S.; Stanca, L.; Dabija, D.-C. Corporate Social Performance: An Assessment Model on an Emerging Market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104077

Crișan-Mitra CS, Stanca L, Dabija D-C. Corporate Social Performance: An Assessment Model on an Emerging Market. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104077

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrișan-Mitra, Cătălina Silvia, Liana Stanca, and Dan-Cristian Dabija. 2020. "Corporate Social Performance: An Assessment Model on an Emerging Market" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104077

APA StyleCrișan-Mitra, C. S., Stanca, L., & Dabija, D.-C. (2020). Corporate Social Performance: An Assessment Model on an Emerging Market. Sustainability, 12(10), 4077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104077