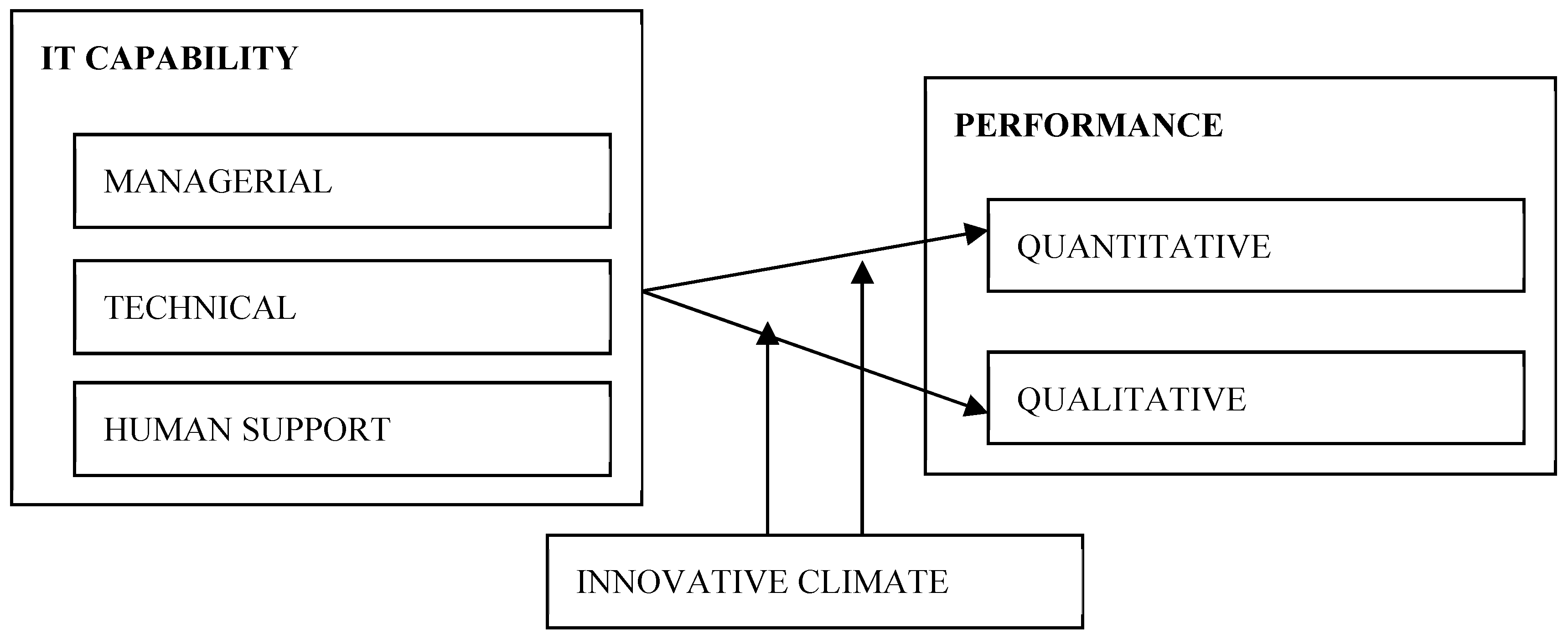

The Role of Innovative Climate in the Relationship between Sustainable IT Capability and Firm Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Search for a New Perspective on the Link between IT and Firm Performance

2.2. The Resource-Based View

2.3. The Market-Driven Perspective

2.4. IT Capability and Sustainability

2.5. Innovative Climate as a Moderating Variable

3. Research Design

3.1. Measures

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Analysis

3.4. Measurement Validation

3.5. Hypothesis Testing

3.6. Structural Model

4. Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Managerial Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measures

References

- Rivard, S.; Raymond, L.; Verreault, D. Resource-based view and competitive strategy: An integrated model of the contribution of information technology to firm performance. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.-W. Information technology capability and value creation: Evidence from the US banking industry. Technol. Soc. 2007, 29, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günsel, A.; Tükel, A. Does Information technology capability improve bank performance? Evidence from Turkey. Int. J. E-Bus. E-Govern. Stud. 2011, 3, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Wetering, R.; Mikalef, P.; Helms, R. Driving organizational sustainability-oriented innovation capabilities: A complex adaptive systems perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 28, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, L.; Yang, F.; Zhu, J. Evaluation of information technology investment: A data envelopment analysis approach. Comput. Oper. Res. 2006, 33, 1368–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.S.; Goraya, M.A.S.; Malik, A.; Aljarallah, A.M. Organizational Performance and Sustainability: Exploring the Roles of IT Capabilities and Knowledge Management Capabilities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strat. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanos, Y.E.; Lioukas, S. An examination into the causal logic of rent generation: Contrasting Porter’s competitive strategy framework and the resource-based perspective. Strat. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 907–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.S. A Resource-Based Perspective on Information Technology Capability and Firm Performance: An Empirical Investigation. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.A.S.; Zhengge, T. The Impact of Organizational Factors on Financial Performance: Building a Theoretical Model. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm. 2015, 2, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Mahoney, J.T. Mutual commitment to support exchange: Relation-specific IT system as a substitute for managerial hierarchy. Strat. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Tang, X. Research Commentary—Information Technology-Enabled Business Models: A Conceptual Framework and a Coevolution Perspective for Future Research. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, G.; Grover, V. Types of Information Technology Capabilities and Their Role in Competitive Advantage: An Empirical Study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccalli, E. Does IT investment improve bank performance? Evidence from Europe. J. Bank. Finance 2007, 31, 2205–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, S.F.; Gunasekaran, A.; Akter, S.; Ren, S.J.-F.; Dubey, R.; Childe, S.J. Big data analytics and firm performance: Effects of dynamic capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, S.S. America’s Technology Dilemma: A Profile of the Information Economy; Morgan Stanley: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gable, G.G.; Sedera, D.; Chan, T. Re-conceptualizing information system success: The IS-impact measurement model. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2008, 9, 377–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.-C.; Koh, C.E.; Park, K.O. Information technology capability and firm performance: Role of industry. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Yang, S. Information technology and productivity: A review of the literature. Adv. Comput. 1996, 43, 179–214. [Google Scholar]

- Barua, A.; Konana, P.; Yin, A.B.W. An Empirical Investigation of Net-Enabled Business Value. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Hitt, L. Information Technology As A Factor Of Production: The Role Of Differences Among Firms. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 1995, 3, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, R.S. Issues in Linking Information Technology Capability to Firm Performance. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Shin, B.; Kwon, O. Investigating the value of socio-materialism in conceptualizing IT capability of a firm. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 327–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Nevo, S.; Benitez, J.; Kou, G. Improving Strategic Flexibility with Information Technologies: Insights for Firm Performance in an Emerging Economy. J. Inf. Technol. 2017, 32, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.; Belitski, M. Dynamic capabilities for firm performance under the information technology governance framework. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2020, 32, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandomi, A.; Haider, M. Beyond the hype: Big data concepts, methods, and analytics. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroufkhani, P.; Wagner, R.; Ismail, W.K.W.; Baroto, M.B.; Nourani, M. Big Data Analytics and Firm Performance: A Systematic Review. Information 2019, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, J.G.; Gurbaxani, V.; Kraemer, K.L. Process Oriented Framework for Assessing the Business Value of Information Technology. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference on Information Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 10–13 December 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, V.S.; Mahapatra, R.K. Exploring the research in information technology implementation. Inf. Manag. 1997, 32, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrecht, F.M.; Ross, C.; Richard, B.; Chappelow, C.C.; Farris, G.F.; Friga, P.N.; Hartz, C.A.; McIlvaine, M.E.; Postle, S.R.; Whitwell, G.E. Knowledge management in research and development. Res. Technol. Manag. 2001, 44, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczak, G.; Sultan, F.; Hultink, E.J. Determinants of IT Usage and New Product Performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2007, 24, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.; Edgett, S.; Kleinschmidt, E. Portfolio management for new product development: Results of an industry practices study. R&D Manag. 2001, 31, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, G. Information Technology in Hotel Management. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2008, 49, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, T.; Lertwongsatien, C. Effect of Information Systems Resources and Capabilities on Firm Performance: A Resource-Based Perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 21, 237–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, I.B.; Akgün, A.E. The roles of it capability and organizational culture on logistics capability and firm performance. J. Bus. Stud. Quart. 2015, 7, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, H.-C.; Koh, C.E.; Prybutok, V.R. Information Technology Capability and Firm Performance: Contradictory Findings and Their Possible Causes. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsonneault, P.P.T. Competing Perspectives on the Link Between Strategic Information Technology Alignment and Organizational Agility: Insights from a Mediation Model. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyver, M.J.; Lu, T.-J. Sustaining Innovation Performance in SMEs: Exploring the Roles of Strategic Entrepreneurship and IT Capabilities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, E.; Guyon, B.; Sheridan, C.; Donnellan, B. Sustainable IT: Challenges, Postures, and Outcomes. Computer 2012, 45, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E. The productivity paradox of information technology. Commun. ACM 1993, 36, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.Y.; Chen, J.-S.; Huang, Y.-H. A framework for investigating the impact of IT capability and organisational capability on firm performance in the late industrialising context. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2006, 36, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakurta, R.; Guha Deb, S. IS/IT investments and firm performance: Indian evidence. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 21, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Hu, J. IT capability as moderator between IT investment and firm performance. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2008, 13, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Schoemaker, P.J.H. Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strat. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E.G. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, S.; Wamba, S.F.; Gunasekaran, A.; Dubey, R.; Childe, S.J. How to improve firm performance using big data analytics capability and business strategy alignment? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 182, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicksen, P.R. The static and dynamic mechanics of competitive theory. J. Market. 1996, 60, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.K.; Fahey, L.; Christensen, H.K. The resource-based view and marketing: The role of market-based assets in gaining competitive advantage. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 777–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.T.; Kirillova, O.M. Reconciling the resource-based and competitive positioning perspectives on manufacturing flexibility. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2011, 22, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, A.Z.; Zehir, C. Kaynaktabanlıişletmeyetenekleriölçeğigeliştirilmesivedoğrulanması (Development and verification of resource-based business capability scales). J. Bus. Adm. Fac. 2008, 8, 103–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Zhao, K.; Kumar, R.L. Impact of IT Governance and IT Capability on Firm Performance. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2016, 33, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; George, J.F. Toward the development of a big data analytics capability. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorfi, S.; Nor, K.M.; Najjar, L. Assessing the Impact of IT Connectivity and IT Capability on IT-Business Strategic Alignment: An Empirical Study. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2011, 4, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.W.; Beath, C.M.; Goodhue, D.L. Develop long-term competitiveness through IT assets, MIT. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.-S.; Tsou, H.-T. Performance effects of IT capability, service process innovation, and the mediating role of customer service. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2012, 29, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bipat, S.; Sneller, L.; Visser, J. What Affects Information Technology Capability: A Meta-Analysis on Aspects that Influence Information Technology Capability. In Proceedings of the AMCIS: Strategic Use, Puerto Rico, USA, 13–15 August 2015; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2015/StrategicUse/GeneralPresentations/2/ (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Ashurst, C.; Crowley, C.; Thornley, C. Executive Briefing: IT Capability Improvement—Key Lessons Learned from Executive Assessments. In Executive Briefing; Innovation Value Institute: Maynooth, Ireland, 2016; Available online: http://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/7561/ (accessed on 7 March 2020).

- Stoel, M.D.; Muhanna, W.A. IT capabilities and firm performance: A contingency analysis of the role of industry and IT capability type. Inf. Manag. 2009, 46, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, N.; Gurbaxani, K.K. Review: Information Technology and Organizational Performance: An Integrative Model of IT Business Value. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.-S.; Lee, J.-N.; Seo, Y.-W. Analyzing the impact of a firm’s capability on outsourcing success: A process perspective. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, F.J.; Fuerst, W.L.; Barney, J.B. Information Technology and Sustained Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based Analysis. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenny, D.; Willcock, L. Capabilities for exploiting IT. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1998, 39, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, G.; Wakefield, R.L.; Kim, S. The effects of IT capabilities and delivery model on cloud computing success and firm performance for cloud supported processes and operations. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-N.; Huynh, M.Q.; Kwok, R.; Pi, S.-M. IT outsourcing evolution: Its past, present, and future. Commun. ACM 2003, 46, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.; Stanley, E. Corporate banking: The strategic impact of boundary spanner effectiveness. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2001, 19, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakin, G.; Keen, P.G.W. Shaping the Future: Business Design Through Information Technology. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1993, 44, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, B.; Tabak, A. The link between organizational agility and leadership: A research in science parks. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Y.E.; Reich, B.H. IT Alignment: What Have We Learned? J. Inf. Technol. 2007, 22, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Montoya-Weiss, M.M. The effect of perceived technological uncertainty on Japanese new product development. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Quan, J.; Zhang, G.; Dubinsky, A.J. Mediation effect of business process and supply chain management capabilities on the impact of IT on firm performance: Evidence from Chinese firms. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, B.; Üstgörül, S. Sustainability of SMEs and Health Sector in a Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. In Challenges and Opportunities for SMEs in Industry 4.0; Ahmad, N., Iqbal, Q., Halim, H., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonton, D.K.; West, M.A.; Farr, J.L. Innovation and Creativity at Work: Psychological and Organizational Strategies. Adm. Sci. Q. 1992, 37, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, J.G. Information technology investment and operational performance in purchasing. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2007, 107, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpay, G.; Bodur, M.; Yılmaz, C.; Cetinkaya, S.; Arıkan, L. Performance implications of institutionalization process in family-owned businesses: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumusluoglu, L.; Ilsev, A. Transformational leadership, creativity, and organizational innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Investment Bank. Banking in Central and Eastern Europe and Turkey—Challenges and Opportunities. Available online: http://www.eib.org (accessed on 5 July 2018).

- Chin, W.W. PLS-Graph User’s Guide; CT Bauer College of Business, University of Houston: Houston, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, R.F.; Hult, G.T.M. Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: An integration and empirical examination. J. Market. 1998, 62, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F.; Cha, J. Partial least squares. Adv. Methods Market. Res. 1994, 18, 52–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research Mahwah: Erlbaum; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publisher: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–358. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis Prentice Hall, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kleijnen, M.; De Ruyter, K.; Wetzels, M.G.M. An assessment of value creation in mobile service delivery and the moderating role of time consciousness. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, A. Customer segmentation with FIMIX-PLS. In Proceedings of the PLS-05 International Symposium, SPAD Test/go, Paris, France, 7 September 2005; pp. 507–514. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A Partial Least Squares Latent Variable Modeling Approach for Measuring Interaction Effects: Results from a Monte Carlo Simulation Study and an Electronic-Mail Emotion/Adoption Study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, N.R.; Premus, R. Modeling The Relationship Between Firm It Capability, Collaboration, And Performance. J. Bus. Logist. 2005, 26, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Boura, M.; Lekakos, G.; Krogstie, J. Big Data Analytics Capabilities and Innovation: The Mediating Role of Dynamic Capabilities and Moderating Effect of the Environment. Br. J. Manag. 2019, 30, 272–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P.K. Towards relationship management: Organisational and workforce restructuring at the Telecom Corporation of New Zealand (TCNZ). N. Z. J. Employ. Relat. 2002, 27, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Gaziano, A.M.; Raulin, M.L. Research Methods: A Process of Inquiry, 2nd ed.; Harper Colleens College Publisheres: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Akgun, A.E.; Keskin, H.; Byrne, J.C.; Aren, S. Emotional and learning capability and their impact on product innovativeness and firm performance. Technovation 2007, 27, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günsel, A.; Açikgöz, A.; Açıkgöz, A. The Effects of Team Flexibility and Emotional Intelligence on Software Development Performance. Group Decis. Negot. 2011, 22, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pee, L.G.; Kankanhalli, A.; Kim, H.W. Knowledge sharing in information systems development: A social interdependence perspective. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2010, 11, 550–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvin, D.A. What does “product quality” really mean? Sloan Manag. Rev. 1984, 26, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Côté, C.; Létourneau, D.; Raïevsky, C.; Brosseau, Y.; Michaud, F. Using marie for mobile robot component development and integration. In Software Engineering for Experimental Robotics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Açıkgöz, A.; Günsel, A.; Bayyurt, N.; Kuzey, C. Team Climate, Team Cognition, Team Intuition, and Software Quality: The Moderating Role of Project Complexity. Group Decis. Negot. 2013, 23, 1145–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, G.C.; Hevner, A.R.; Collins, R.W. The impacts of quality and productivity perceptions on the use of software process improvement innovations. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2005, 47, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajila, S.; Wu, D. Empirical study of the effects of open source adoption on software development economics. J. Syst. Softw. 2007, 80, 1517–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; El Sawy, O.A.; Fiss, P. The Role of Business Intelligence and Communication Technologies in Organizational Agility: A Configurational Approach. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2017, 18, 648–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Krogstie, J. Examining the interplay between big data analytics and contextual factors in driving process innovation capabilities. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Studies | Key Variables | Research Type |

|---|---|---|

| Mata et al., 1995 |

| Conceptual |

| Ross et al., 1996 |

| Conceptual |

| Fenny/Willcoks 1998 |

| Conceptual |

| Bharadwaj 2000 |

| Conceptual |

| Basellier et al., 2001 |

| Empirical |

| Lee et al., 2003 |

| Empirical |

| Melville et al., 2004 |

| Conceptual |

| Ravichandran/Lertwongsatien 2005 |

| Empirical |

| Lin 2007 |

| Empirical |

| Han et al., 2008 |

| Empirical |

| Günsel/Tükel 2011 |

| Empirical |

| Chen/Tsou 2012 |

| Empirical |

| Kim et al., 2012 |

| Conceptual |

| Garrison et al., 2015 |

| Empirical |

| No | Mean | Standard Deviation | Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.52 | 0.80 | MIT | 0.84 | |||||

| 2 | 3.65 | 0.82 | TIT | 0.796 ** | 0.80 | ||||

| 3 | 3.35 | 0.93 | HCS | 0.634 ** | 0.581 ** | 0.87 | |||

| 4 | 3.66 | 0.88 | InC | 0.465 ** | 0.540 ** | 0.616 ** | 0.77 | ||

| 5 | 3.88 | 0.81 | QnP | 0.442 ** | 0.532 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.392 ** | 0.89 | |

| 6 | 3.79 | 0.80 | QlP | 0.522 ** | 0.571 ** | 0.654 ** | 0.641 ** | 0.780 ** | 0.85 |

| CR | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.87 | |||

| AVE | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.79 | 0.72 | |||

| α | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.91 |

| Relationships | Path Coefficient (β) | Sub-Hypotheses | Sub-Results | Hypotheses | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIT | → | QnP | 0.34 ** | H1a | Supported | H1 | Partially Supported |

| TIT | → | QnP | 0.21 ** | H1b | Supported | ||

| HCS | → | QnP | 0.22 | H1c | Not Supported | ||

| MIT | → | QlP | 0.25 ** | H2a | Supported | H2 | Fully Supported |

| TIT | → | QlP | 0.19 * | H2b | Supported | ||

| HCS | → | QlP | 0.43 ** | H2c | Supported | ||

| MIT * InC | → | QnP | 0.06 | H3a | Not Supported | H3 | Marginally Supported |

| TIT * InC | → | QnP | 0.17 * | H3b | Supported | ||

| HCS * InC | → | QnP | 0.07 | H3c | Not Supported | ||

| MIT * InC | → | QlP | 0.23 ** | H4a | Supported | H4 | Partially Supported |

| TIT * InC | → | QlP | 0.22 ** | H4b | Supported | ||

| HCS * InC | → | QlP | 0.05 | H4c | Not Supported | ||

| Fit Measures | Endogenous Constructs | Main Effect Model | Final Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| QnP | 0.28 | 0.32 | |

| QlP | 0.40 | 0.57 | |

| GoF | 0.49 | 0.61 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erkmen, T.; Günsel, A.; Altındağ, E. The Role of Innovative Climate in the Relationship between Sustainable IT Capability and Firm Performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104058

Erkmen T, Günsel A, Altındağ E. The Role of Innovative Climate in the Relationship between Sustainable IT Capability and Firm Performance. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104058

Chicago/Turabian StyleErkmen, Turhan, Ayşe Günsel, and Erkut Altındağ. 2020. "The Role of Innovative Climate in the Relationship between Sustainable IT Capability and Firm Performance" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104058

APA StyleErkmen, T., Günsel, A., & Altındağ, E. (2020). The Role of Innovative Climate in the Relationship between Sustainable IT Capability and Firm Performance. Sustainability, 12(10), 4058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104058