Drivers and Constraints to the Adoption of Organic Leafy Vegetable Production in Nigeria: A Livelihood Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

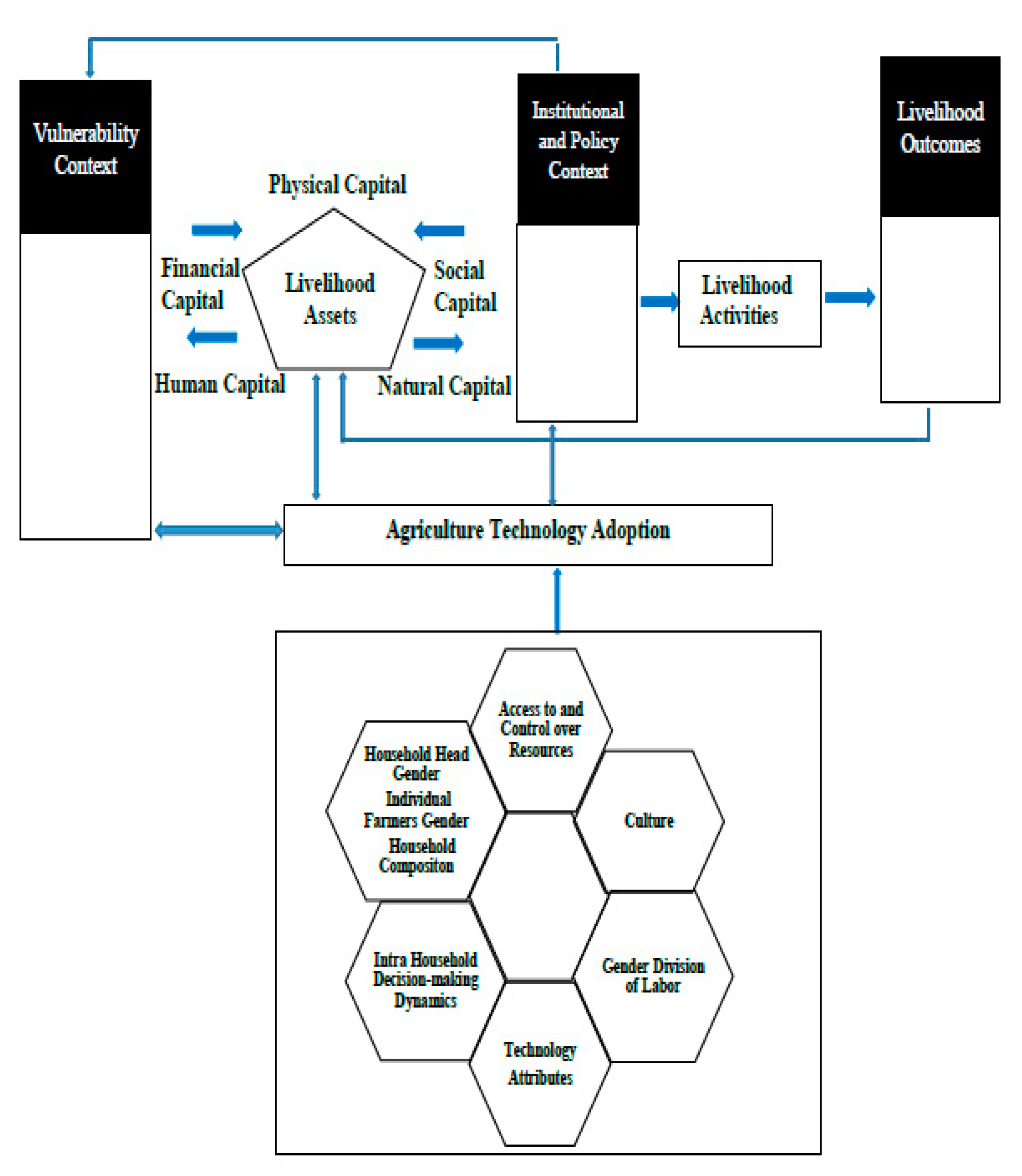

2. Delineating and Characterizing Adoption Decision-Making

3. Conceptual Framework

4. Methods

4.1. Study Sites

4.2. Respondent Selection

4.3. In-Depth Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Groups

4.4. Participant Observations, Field Visits, and Group Discussions

4.5. Expert Interviews and Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Drivers of Adoption Decision

5.1.1. Livelihood Assets

5.1.2. Vulnerability Context

5.1.3. Institutional and Policy Context

5.1.4. Livelihood Activities

5.1.5. Livelihood Outcomes

5.1.6. Technology Attributes

5.1.7. Culture

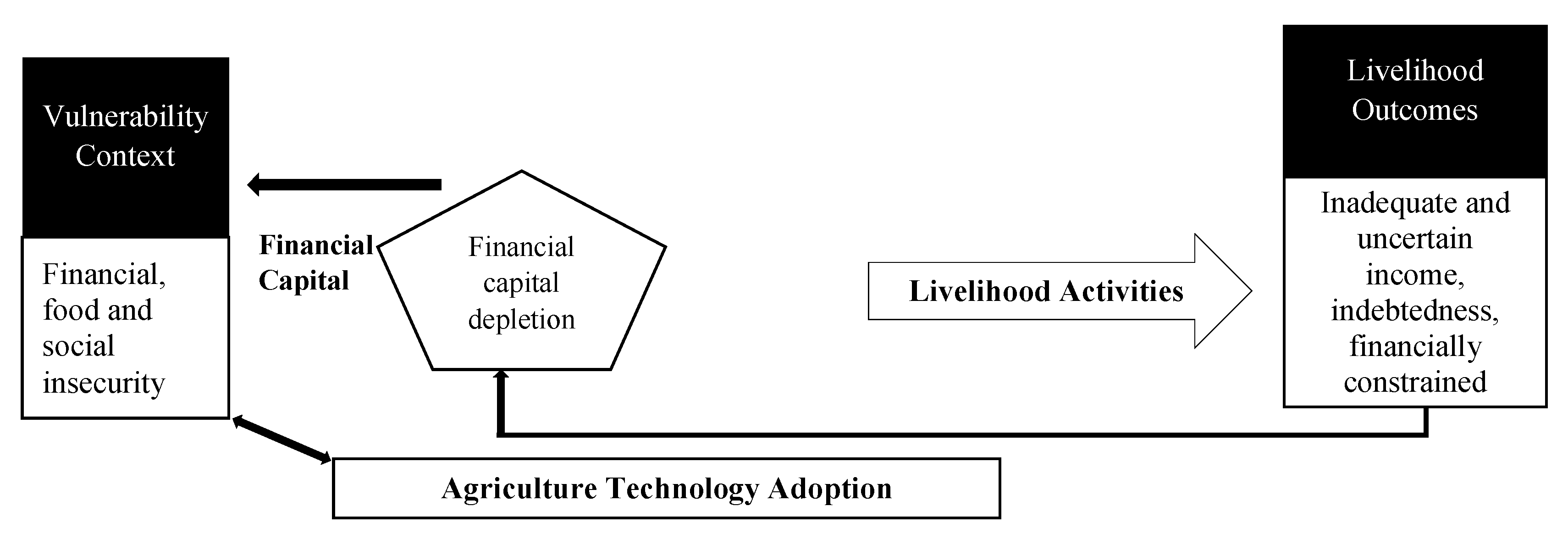

5.2. Factors in Non-Adopters’ Decision-Making

5.2.1. Livelihood Assets

5.2.2. Vulnerability Context

5.2.3. Institutional and Policy Context

5.2.4. Livelihood Outcomes

5.2.5. Technology Attributes

5.2.6. Gender Division of Labor, Intrahousehold Decision-Making Dynamics

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP-UNCTAD. Organic Agriculture and Food Security in Africa; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mamuya, W.B. Assessing the Impacts of Organic Farming on Domestic and Exporting Smallholder Farming Households in Tanzania: A Comparative Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Bangor University, Whales, UK, October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Adebiyi, J.A. Organic Agriculture Development Strategies in Tunisia and Uganda: Lessons for African Organics. Master’s Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bakewell-Stone, P. Sustaining Livelihoods through Organic Agriculture in Tanzania: A Sign-Post for the Future. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, As, Norway, May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kisaka-Lwayo, M.; Obi, A. Analysis of Production and Consumption of Organic Products in South Africa. In Organic Agriculture towards Sustainability; Pilipavicius, V., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2014; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmann, H.; Bergström, L.; Kätterer, T.; Andrén, O.; Andersson, R. Can organic crop production feed the world? In Organic Crop Production—Ambitions and Limitations; Kirchmann, H., Bergström, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lotter, D. Facing food insecurity in Africa: Why, after 30 years of work in organic agriculture, I am promoting the use of synthetic fertilizers and herbicides in small-scale staple crop production. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, D.; Adamtey, N.; Messmer, M.M.; Pfiffner, L.; Baker, B.; Huber, B.; Niggli, U. Organic agriculture-driving innovations in crop research. In Agricultural Sustainability-Progress and Prospects in Crop Research; Bhullar, G.S., Bhullar, N.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- IFOAM. Participatory Guarantee Systems: Case Studies from Brazil, India, New Zealand, USA; IFOAM: Bonn, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Atungwu, J.J.; Agbonlahor, M.U.; Aiyelaagbe, I.O.O.; Olowe, V.I. Community-based farming scheme in Nigeria: Enhancing sustainable agriculture. In How Innovations in Market Institutions Encourage Sustainable Agriculture in Developing Countries; Loconto, A., Poisot, A.S., Santacoloma, P., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016; pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Oyewole, M.F. Gender involvement in ecological organic crop farming in Ogun State. In Proceedings of the 3rd African Organic Conference, Lagos, Nigeria, 5–9 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dipeolu, A.O.; Philip, B.B.; Aiyelaagbe, I.O.O.; Akinbode, S.O.; Adedokun, T.A. Consumer awareness and willingness to pay for organic vegetables in southwest Nigeria. Asian J. Food Ag-Ind. 2009, 10, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Obayelu, O.A.; Agboyinu, O.M.; Awotide, B.A. Consumers’ perception and willingness to pay for organic leafy vegetables in urban Oyo State, Nigeria. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2014, 4, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenegan, K.O.; Fatai, R.A. Market potentials for selected organic leafy vegetables. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2016, 22, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagensen, J.; Atungwu, J.A. Glance of the enthusiastic development of the organic sector in Nigeria. ICROFS News 2010, 4, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. The sleeping organic giant of Africa: Nigeria. Ecol. Farming 2011, 5, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, M.B.; Abdulai, A. Evaluating preferences for organic product attributes in nigeria: Attribute non-attendance under explicit and implicit priming task. In Proceedings of the AAEA and WAEA Joint Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–28 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oyawole, F.P.; Akerele, D.; Dipeolu, A.O. Factors influencing willingness to pay for organic vegetables among civil servants in a developing country. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2016, 22, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyesola, O.B.; Obabire, I.E. Farmers’ perceptions of organic farming in selected local government areas of Ekiti State, Nigeria. J. Org. Syst. 2011, 6, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Adesope, O.M.; Matthews-Njoku, E.C.; Oguzor, N.S.; Ugwuja, V.C. Effect of socio-economic characteristics of farmers on their adoption of organic farming practices. In Crop Production Technologies; Sharma, P., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Phillip, B.; Dipeolu, A.O. Willingness to pay for organic vegetables in Abeokuta, south west Nigeria. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2010, 10, 4364–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanfeoluwa, O.E.; Adekunle, A.F.; Kayode, C.O.; Ogunleti, D.O.; Opebiyi, E.T. Report on Activity 3.1.5 Supporting Stakeholders to Collect, Analyze and Disseminate Market Information and Data; Federal College of Agriculture, Moor Plantation, Ibadan, and Ecological Organic Agriculture (EOA) in Nigeria: Lagos, Nigeria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, S.S.; Catacutan, D.; Ajayi, O.C.; Sileshi, G.W.; Nieuwenhuis, M. The role of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions in the uptake of agricultural and agroforestry innovations among smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2015, 13, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabisi, L.S.; Wang, R.Q.; Ligmann-Zielinska, A. Why don’t more farmers go organic? Using a stakeholder-informed exploratory agent-based model to represent the dynamics of farming practices in the Philippines. Land 2015, 4, 979–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazziwa-Nviiri, L.; van Campenhout, B.; Amwonya, D. Stimulating Agricultural Technology Adoption: Lessons from Fertilizer Use among Ugandan Potato Farmers; IFPRI: Kampala, Uganda, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D.K.; Norvell, J.; Sonka, S.; Nelson, M.J. Understanding technology adoption through system dynamics modeling: Implications for agribusiness management. Int. Food Agribus. Man. 2000, 3, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.P.; Cameron, D.; Nguyen, X.T. Rural livelihood adoption framework: A conceptual and analytical framework for studying adoption of new activities by small farmers. Int. J. Agric. Manag. 2015, 4, 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Straub, E.T. Understanding technology adoption: Theory and future directions for informal learning. Educ. Res. Rev. 2009, 79, 625–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguthi, F.N. Adoption of Agricultural Innovations by Smallholder Farmers in the Context of HIV/AIDS: The Case of Tissue-Cultured Banana in Kenya; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- van Eerdewijk, A.; Danielsen, K. Gender Matters in Farm Power; KIT: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Beuchelt, T.D. Gender, social equity and innovations in smallholder farming systems: Pitfalls and pathways. In Technological and Institutional Innovations for Marginalized Smallholders in Agricultural Development; Gatzweiler, F.W., von Braun, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- van den Broeck, G.; Grovas, R.R.P.; Maertens, M.; Deckers, J.; Verhulst, N.; Govaerts, B. Adoption of conservation agriculture in the Mexican Bajio. Outlook Agric. 2013, 42, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedzisa, T.; Rugube, L.; Winter-Nelson, A.; Baylis, K.; Mazvimavi, K. The intensity of adoption of conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. Agrekon 2015, 54, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyhorn, F. Organic Farming for Sustainable Livelihoods in Developing Countries: The Case of Cotton in India. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany, 30 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, G.B.; Rattanasuteerakul, K. Adoption and extent of organic vegetable farming in Mahasarakham province, Thailand. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polar, V.; Babini, C.; Velasco, C.; Flores, P.; Fonseca, C. Technology is not Gender Neutral: Factors that Influence the Potential Adoption of Agricultural Technology by Men and Women; International Potato Center: La Paz, Bolivia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Adato, M.; Meinzen-Dick, R.S. Assessing the Impact of Agricultural Research on Poverty using the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework; IFPRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Monroy, L.; Potts, S.G.; Tzanopoulos, J. Drivers influencing farmer decisions for adopting organic or conventional coffee management practices. Food Policy 2016, 58, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, H.H.; Barkley, A.; Chacón-Cascante, A.; Kastens, T.L. The motivation for organic grain farming in the United States: Profits, lifestyle, or the environment? J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2012, 44, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Doss, C.R.; Morris, M.L. How does gender affect the adoption of agricultural innovations? The case of improved maize technology in Ghana. Agric. Econ. 2000, 25, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwira, A.; Johnsen, F.H.; Aune, J.B.; Mekuria, M.; Thierfelder, C. Adoption and extent of conservation agriculture practices among smallholder farmers in Malawi. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2014, 69, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyetunji, O.J.; Osonubi, O.; Ekanayake, I.J. Contributions of an alley cropping system and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to maize productivity under cassava intercrop in the derived savannah zone. J. Agric. Sci. 2003, 140, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayande, W.A.; Mohammed, G.; Caleb, I.; Deimodei, M.I. Assessment of urban flood disaster: A case study of 2011 Ibadan floods. Niger. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 2012, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Oshunsanya, S.O.; Adeniran, T.O. Water quality and crop contamination in peri-urban agriculture. Agricultura Tropica et Subtropica 2014, 47, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanlauwe, B.; Diels, J.; Sanginga, N.; Merckx, R. Long-term integrated soil fertility management in South-western Nigeria: Crop performance and impact on the soil fertility status. Plant Soil 2005, 273, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberg, L.A. Organic Certification Systems and Farmers’ Livelihoods in New Zealand; Lincoln University: Lincoln, New Zealand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- DFID. Sustainable livelihoods Guidance Sheets, Numbers 1–8; DFID: London, UK, 1999.

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods and Poverty Elimination; DFID: London, UK, 1999.

- Kaup, B.Z. The reflexive producer: The influence of farmer knowledge upon the use of Bt corn. Rural Sociol. 2008, 73, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovignan, D.S.; Nuppenau, E.A. Adoption of Organic Cotton in Benin: Does Gender Play a Role. Presented at Conference on Rural Poverty Reduction through Research for Development and Transformation, Deutscher Tropentag, Berlin, Germany, 5–7 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, L.; Klonsky, K.; Strochlic, R.; Brodt, S.; Molinar, R. Factors Associated with Deregistration among Organic Farmers in California; California Institute for Rural Studies Davis: Davis, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Adopters | Non-Adopters | Experts | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | NOAN | Gov. |

| Ajibode | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Akinyele | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Elekuru | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 15 | 10 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Group | Location | Participants in FGDs | Total | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adopters | Ajibode | Male only | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Adopters | Ajibode | Female only | 15 | 15 | 0 |

| Non-Adopters | Ajibode | Mixed | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Adopters | Akinyele | Male only | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Adopters | Elekuru | Male only | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Adopters | Elekuru | Female only | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| Non-Adopters | Elekuru | Mixed | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 49 | 27 | 22 |

| Livelihood Activities | % of Total Respondent | Number of Respondents | Distribution Across Study Areas | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajibode | Akinyele | Elekuru | |||

| Farming only | 27 | 4 | Nil | Nil | 4 |

| Male | 2 | Nil | Nil | 2 | |

| Female | 2 | Nil | Nil | 2 | |

| Farming and off-farm | 73 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 1 |

| Male | 8 | 3 | 4 | 1 | |

| Female | 3 | 3 | Nil | Nil | |

| TALAF Component | Caused/Facilitated by | Related to | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Livelihood Assets-Human Financial, And Social Capital | Awareness/knowledge of organic farming and of ill-health with farm chemicals (human capital) | Contact with the promoters of organic and extension access/technical support (institutional) | Social capital, e.g., family ties, church membership, and relationship of trust with fellow farmers and the promoters of organic farming |

| Experiential knowledge (human capital) | Awareness of the ill-health issues with farm chemicals | Knowledge of forefather’s agriculture and experience growing some crops with(out) chemicals | |

| Difficulty getting money to buy chemicals (women; financial capital) | Financial situation | Cost of chemical inputs | |

| Social status in the community (social capital) | Religious/community leadership | ||

| Vulnerability Context | Indebtedness, financial problems, and food insecurity | Off-farm livelihood activities not generating a stable and good income | |

| Farm income losses | Market insecurity/adverse prices for conventional produce (institutional) | ||

| Social insecurity (women) | Financial situation and spousal household relations | ||

| Susceptibility to sickness | Ill-health with farm chemicals | ||

| Institutional and Policy Context | Training/extension technical support on organic farming | NOAN; social capital ties | |

| Organic “premium” market opportunity | |||

| Livelihood Activities | Farm and off-farm livelihood activities | Insufficient income from livelihood activities | |

| Livelihood Outcomes (Expected) | Economic motivations, e.g., raise money, obtain profitable income, and gain access to “premium” markets | Access to high price-paying markets for organic farming (institutional) | |

| Health–food safety motivations-improved personal, family, and societal health condition; food-safety concerns; and longevity of life | Awareness of perceived health benefits of organic/ill-health issues with farm chemicals (human capital) | ||

| Improved soil heath and preventing environmental pollution | Exclusion of synthetic inputs | ||

| Technology Attributes | Low-cost | Exclusion of synthetic inputs (institutional) | Women financial situation |

| Compatibility with forefathers’ agriculture and perceived health benefits | |||

| Relative profitability | Access to high price-paying markets for organic farming (institutional); exclusion of synthetic inputs | ||

| Culture | Forefather agricultural heritage | Notion of ideal agriculture, good and healthy food, and organic farming attributes/perceived health benefits | |

| TALAF Component | Caused by/Related to | |

|---|---|---|

| Livelihood Assets: human and social capital | Limited awareness/knowledge of organic farming | Lack of extension access about organic farming (institutional) |

| Household labor limitation | Family size/children education (household composition) | |

| Limited physical capacity for manual weeding and land clearing in organic farming (women) | Technology attribute-exclusion of chemicals in organic farming, and domestic gender division of labor, e.g., cooking | |

| Church membership | Different church affiliation | |

| Vulnerability Context | Perceived susceptibility to yield and financial losses, and hunger | Insect pest problems; exclusion of chemicals in organic farming (institutional), farm location in swampy areas (natural capital), harmattan and occasional heavy rainfall in dry season, and dearth of markets for organic farming (institutional) |

| Perceived susceptibility to hunger | Duration for organic crops to mature for harvest and sales | |

| Institutional and Policy Context | Dearth of organic farming “premium” markets Organic farming market access/marketing problems (Elekuru) | Conventional and organic farmers selling on the same markets, and poor consumer awareness of organic farming, especially in rural Elekuru |

| Lack of extension support | ||

| Prohibition of burning/chemical in organic | NOAN PGS certification rules | |

| Lack of financial support to hire labor/access organic farming input | Labor need/cost in organic farming, perception that organic farming is not economically rewarding, and limited household labor | |

| Distrust in the organization promoting organic farming | ||

| Livelihood Outcomes | Low crop yield, and low/unprofitable income in organic farming | Exclusion of chemicals in organic farming, dearth/lack of market for organic produce (institutional), desire for quick and high income, and higher yield and income from conventional farming |

| Lack of observable economic benefits from organic farming | Income, profit, and price obtained by organic farmers for their produce, and market access by organic farmers | |

| Technology Attributes | Physically challenging, and labor- and time-intensive | Exclusion of chemicals in organic farming (institutional), and gendered domestic role by female farmers |

| High-risk (income/financial losses); low crop yielding technology | Vulnerability of organic crops to insect pest attack, and exclusion of farm chemicals | |

| High-cost | Labor need and labor cost in organic farming, and exclusion of weed killers | |

| Gender Division of Labor | Domestic role played by women, e.g., cooking | Intrahousehold gender relations via decision-making authority of men over women’s time, organic farming as time-intensive, and lack of time due to domestic roles |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adebiyi, J.A.; Olabisi, L.S.; Richardson, R.; Liverpool-Tasie, L.S.O.; Delate, K. Drivers and Constraints to the Adoption of Organic Leafy Vegetable Production in Nigeria: A Livelihood Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010096

Adebiyi JA, Olabisi LS, Richardson R, Liverpool-Tasie LSO, Delate K. Drivers and Constraints to the Adoption of Organic Leafy Vegetable Production in Nigeria: A Livelihood Approach. Sustainability. 2020; 12(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdebiyi, Jelili Adegboyega, Laura Schmitt Olabisi, Robert Richardson, Lenis Saweda O Liverpool-Tasie, and Kathleen Delate. 2020. "Drivers and Constraints to the Adoption of Organic Leafy Vegetable Production in Nigeria: A Livelihood Approach" Sustainability 12, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010096

APA StyleAdebiyi, J. A., Olabisi, L. S., Richardson, R., Liverpool-Tasie, L. S. O., & Delate, K. (2020). Drivers and Constraints to the Adoption of Organic Leafy Vegetable Production in Nigeria: A Livelihood Approach. Sustainability, 12(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010096