Explaining Urban Sustainability to Teachers in Training through a Geographical Analysis of Tourism Gentrification in Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Goal

1.2. State of the Research Field

1.2.1. Tourism Gentrification

1.2.2. Geographical Fieldworks and Fieldtrips

2. Materials and Methods: Activity Design

2.1. Aim and Presentation

2.2. Objectives and Competences

- 1.

- To be able to analyse educational concepts and theories and educational policy issues in a systematic way.

- 2.

- To be able to identify the potential links between knowledge and its application to educational policies and contexts.

- 3.

- To be conscious about one’s own system of values.

- 5.

- To be capable of recognising the diversity of students and the complexities of the learning process.

- 6.

- To be aware of the different contexts in which learning can take place.

- 7.

- To be aware of the different roles of those who participate in the learning process.

- 9.

- To be able to conduct an educational research in different contexts.

- 11.

- To be able to manage projects for improvement and school development.

- 12.

- To be able to manage educational programs.

- 13.

- To be able to evaluate educational programs and materials.

- 14.

- To be able to anticipate new educational needs and demands.

- 15.

- To be able to lead or coordinate multidisciplinary educational teams.

- 17.

- To be competent in various teaching/learning strategies.

- 19.

- To know the subject matter to be taught.

- 20.

- To be able to communicate effectively with groups and individuals.

- 21.

- To be able to create a climate that facilitates learning.

- 23.

- To be able to manage time effectively.

- 25.

- To be aware of the need for continuous professional development.

- 26.

- To be able to evaluate the learning outcomes and student achievement.

- 27.

- To be competent in collaborative problem solving.

- 29.

- To be able to respond to the diverse needs of the students.

- 30.

- To be able to adapt the curriculum to a specific educational context.

2.3. Didactic Evaluation

2.4. Choice of Study Districts

3. Results and Discussion of an Implemented Experience

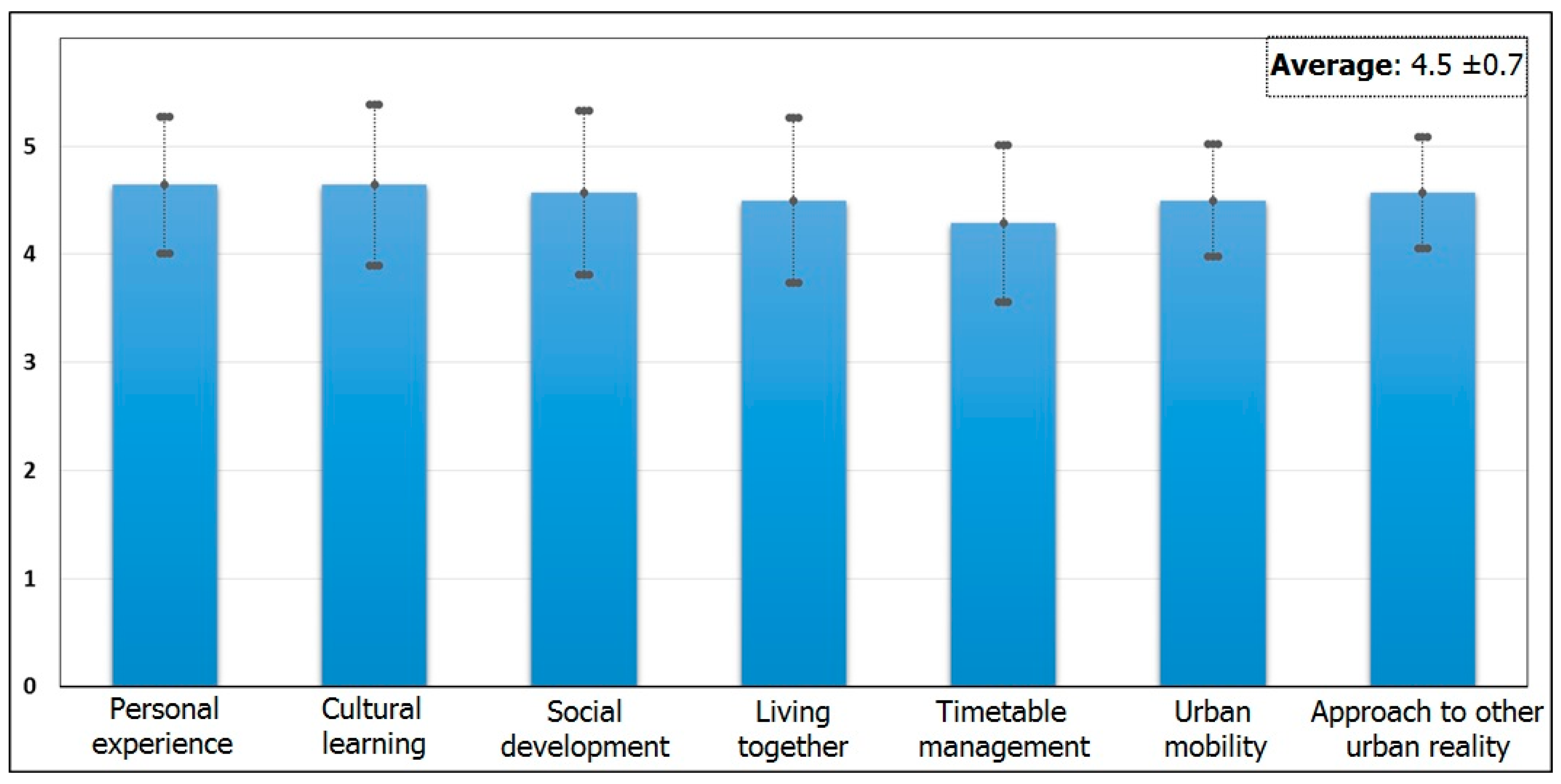

3.1. Degree of Achievement of the Objectives According to the Students’ Perception

3.2. Degree of Achievement of the Objectives Based on Evaluation Questions

3.3. Degree of Achievement of the Objectives from the Students’ Production

3.4. The Geographical Fieldwork as an Integral Experience

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santamaria, D.; Filis, G. Tourism demand and economic growth in Spain: New insights based on the yield curve. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo Malvárez, M. New uses of heritage sites: The expansion of boutique hotels in Palma (Mallorca). Estoa 2019, 16, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.; Page, S.J. Urban tourism research: Recent progress and current paradoxes. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, M.; De la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Yubero, C. Cultural heritage and urban tourism: Historic city centres under pressure. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravari-Barbas, M.; Guinand, S. Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, J. The Scientification of tourism. Política Soc. 2005, 42, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- De Lázaro y Torres, M.L. Educar para el desarrollo sostenible desde la Geografía. In Aportaciones de la Geografía en el Aprendizaje a lo Largo de la Vida; Delgado Peña, J.L., de Lázaro y Torres, M.L., Marrón Gaite, M.J., Eds.; University of Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2011; pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, T.; Taillon, L.; Dredge, D. Sustainable tourism pedagogy and academic community collaboration: A progressive service-learning approach. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebezac, D.; Schott, C.; Sheldon, P. The Tourism Education Futures Initiative. Activating Change in Tourism Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Belhassen, Y.; Caton, K. On the need for critical pedagogy in tourism education. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Sánchez, D. La enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales, las TIC y el tratamiento de la información y competencia digital (TICD) en el Grado de Maestro/a de Educación Primaria de las universidades de Castilla y León. Enseñanza Cienc. Soc. 2015, 14, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Dogru, T.; Bulut, U. Is tourism an engine for economic recovery? Theory and empirical evidence. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerval, A.; Colomb, C.; van Crieckingen, M. Les gentrifications des métropoles européennes. In Données Urbaines; Pumain, D., Mattei, M.F., Eds.; Economica Anthropos: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Cocola-Gant, A. Tourism and commercial gentrification. In Proceedings of the RC21 International Conference on the Ideal City: Between Myth and Reality. Representations, Policies, Contradictions and Challenges for Tomorrow’s Urban Life, Urbino, Italy, 27–29 August 2015; Available online: https://www.rc21.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/E4-C%C3%B3cola-Gant.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Aalbers, M. Introduction to the forum: From third to fifth-wave gentrification. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2019, 110, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.F. Tourism gentrification: The case of New Orleans’ Vieux Carré (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth, D.; Weiser, A. Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2018, 50, 1147–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S.S.; Gladstone, D. Evaluating urban tourism. In The Tourist City; Judd, D.R., Fainstein, S., Eds.; Yale University Press: London, UK, 1999; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Degen, M. Barcelona’s games: The Olympics, urban design, and global tourism. In Tourism Mobilities: Places to Play, Places in Play; Sheller, M., Urry, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Renal, L.; Lara Martín, L. Del barrio-problema al barrio de moda: Gentrificación comercial en Russa-fa, el “Soho” valenciano. An. Geogr. 2015, 35, 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. Naked City. The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, D.R. Visitors and the spatial ecology of the city. In Cities and Visitors: Regulating People, Markets, and City Space; Hoffman, L., Fainstein, S., Judd, D.R., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, J. Ordinary tourism and extraordinary everyday life: Re-thinking tourism and cities. In Tourism and Everyday Life in the City; Frisch, T., Stors, N., Stoltenberb, L., Sommer, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze. Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Maitland, R. Everyday life as a creative experience in cities. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2010, 4, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiernaux, D.; Gonzalez, I. Turismo y gentrificación: Pistas teóricas sobre una articulación. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2014, 58, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. A global sense of place. Marx. Today 1991, 38, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, T.; Lees, L. Super-gentrification in Barnsbury, London: Globalization and gentrifying global elites at the neighborhood level. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2006, 31, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitland, R. Conviviality and everyday life: The appeal of new areas for visitors. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füller, H.; Michel, B. ‘Stop being a tourist!’ New dynamics of urban tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuis, A.; Gravari-Barbas, M.; Jacquot, S. Tourism/gentrification: Sex, gender and crossed resistances. In Proceedings of the Association of American Geographers Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 21–25 April 2015; Available online: www.academia.edu/12256317/Tourism_Gentrification_Sex_gender_and_crosses_resistances (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- Baudry, S.L. Rome: A cultural capital with a poor working-class heritage: Strategies of touristification and artification. In Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises; Gravari-Barbas, M., Guinand, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 134–152. [Google Scholar]

- Freitag, T.; Bauder, M. Bottom-up touristification and urban transformations in Paris. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malet Calvo, D.; Gago, A.; Cócola-Gant, A. Turismo, negocio inmobiliario y movimientos de resistencia en Lisboa, Portugal. In Ciudad de Vacaciones. Conflictos Urbanos en Espacios Turísticos; Milano, C., Mansilla, J.A., Eds.; Pololen Edicions, Observatori Antropologia del Conflicte Urbá: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; pp. 121–153. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Mendes, L.; Guimarães, P.P.C. Tourism and urban changes: Lessons from Lisbon. In Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises; Gravari-Barbas, M., Guinand, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Benis, K. Vielas de Alfama. Entre Revitalização e Gentrificação. Impactos da «Gentrificação» Sobre a Apropriação do Espaço Público; Universidade Técnica de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Quaglieri, A.; Scarnato, A. The Barrio Chino as last frontier: The penetration of everyday tourism in the dodgy heart of the Raval. In Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises; Gravari-Barbas, M., Guinand, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 107–135. [Google Scholar]

- Maiello, V. El mercado de los mercados. Análisis de los procesos de transformación de los mercados municipales de abastos de Madrid. In Working Paper Series—Contested Cities; Grupo de Trabajo Mercados y Espacios Públicos ASF-Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Available online: http://contested-cities.net/working-papers/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2014/03/WPCC-14016_Maiello_vincenzo_elmercadodelosmercados.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Pérez, E. Gentrificación en Madrid: De la burbuja a la crisis. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2013, 58, 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Sequera, J.; Janoshka, M. Gentrification dispositifs in the historic centre of Madrid: A reconsideration of an urban governmentality and state-led urban gentrification. In Global Gentrifications: Uneven Development and Displacement; Lees, L., Shin, H., López-Morales, E., Eds.; Polity Press: London, UK, 2015; pp. 375–394. [Google Scholar]

- Colomb, C.; Novy, J. Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Piñeros, D.; Vásquez Ortiz, W.F.; Rodríguez Pizzinato, L.A. La salida de campo, una posibilidad en la formación inicial docente. Didáctica Cienc. Exp. Soc. 2016, 31, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, D. La salida de campo como recurso didáctico para enseñar ciencias. Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Eureka Sobre Enseñanza Divulg. Cienc. 2018, 15, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo Castellanos, J.M.; Gómez Ruiz, M.L.; Cruz Naïmi, L.A. Una aproximación a los Parques Nacionales y sus paisajes a través de itinerarios didácticos. Espac. Tiempo Forma 2018, 11, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council for Learning outside the Classroom. Learning Outside the Classroom. Manifesto; DfES Publications: Nottingham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rajala, A.; Akkerman, S.F. Researching reinterpretations of educational activity in dialog interactions during a fieldtrip. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2019, 20, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Toro, R.; Morcillo, J.G. Las actividades de campo en educación secundaria. Un estudio comparativo entre Dinamarca y España. Enseñanza Cienc. Tierra 2011, 19, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino, A.V.; Bell, P.E. A comparison of attributed values with empirically determined values of secondary school science field trips. Sci. Educ. 1970, 54, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrinaci, E. Trabajo de campo y aprendizaje de las ciencias. Alambique 2012, 71, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo, D.; Marqués, L.; Costa, N. Actividades en ambientes exteriores al aula en la educación en ciencias: Contribuciones para su operatividad. Enseñanza Cienc. Tierra 2011, 19, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Turman, C. The outdoor classroom program: Fieldtrips empowered by technology. In Proceedings of the 12th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 5–7 March 2018; Chova, L.G., Martínez, A.L., Torres, I.C., Eds.; pp. 7534–7537. [Google Scholar]

- Costillo, E.; Borrachero, A.B.; Esteban, R.; Sánchez-Martín, J. Aportaciones de las salidas al medio natural como actividades de enseñanza y de aprendizaje según profesores en formación. Indagatio Didáctica 2014, 6, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sagir, S.U. Reviewing science and nature activities of preschool teachers. Energy Educ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 3, 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado Trujillo, A.; de Justo Moscardó, E. Evaluación del diseño, proceso y resultados de una asignatura técnica con aprendizaje basado en problemas. Educ. XX1 2018, 21, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solbes, J. ¿Por qué disminuye el alumnado de ciencias? Alambique 2011, 67, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cañas, A.; Martín-Díaz, M.J. ¿Puede la competencia científica acercar la ciencia a los intereses del alumnado? Alambique 2010, 66, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, C.J.; Miralles, P.; López, R.; Prats, J. Las competencias históricas en el horizonte. Propuestas presentes y perspectivas de futuro. In Enseñanza de la Historia y Competencias Educativas; López, R., Miralles, P., Prats, J., Eds.; Graó Ed.: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; pp. 215–227. [Google Scholar]

- EHES. European Higher Education Space. Available online: http://www.eees.es/es/eees-estructuras-educativas-europeas (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- González, J.; Wagenaar, R. Tuning Educational Structures in Europe II; University of Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Burriel, E. La ‘década prodigiosa’ del urbanismo español (1997–2006). Scr. Nova Rev. Electrónica Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2008, XII, 64. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-270/sn-270-64.htm (accessed on 8 October 2019).

- Fernández Portela, J. La salida de campo como recurso didáctico para conocer el espacio geográfico: El caso de la ciudad de Valladolid y Soria. Didáctica Geográfica 2017, 18, 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- De Lázaro y Torres, M.L.; Izquierdo Álvarez, S.; González González, M.J. Geodatos y paisaje: De la nube al aula universitaria. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2016, 70, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, L.S.; Vega, N.; Capa, E.D.; Fierro, N.C.; Quichimbo, P. Estilos y estrategias de enseñanza-aprendizaje de estudiantes universitarios de la ciencia del suelo. REDIE 2019, 21, e04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Cortés, A.B.; Díaz Velasco, E.A.; Carreño Cardozo, J.M. Turismo como agente educativo: Un análisis desde las salidas de campo. Tur. Soc. 2015, 16, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Peral, J.L. Salida de campo por el valle del Henares y su canal de riego. Tarbiya Rev. Investig. Innovación Educ. 2018, 46, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde Fernández, F.; Ramírez García, A.; Mora Márquez, M.; López Fernández, J.A.; Medina Quintana, S.; Arrebola Haro, J.C. Itinerarios interdisciplinares en el grado de educación primaria. Rev. Innovación Buenas Prácticas Docentes 2018, 6, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, S.; García, D.; Souto, X. Educación geográfica y las salidas de campo como estrategia didáctica: Un estudio comparativo desde el Geoforo Iberoamericano. Biblio3W Rev. Bibliográfica Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2016, 155, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, J.; Rickinson, M.; Tearney, K.; Morris, M.; Choi, M.-Y.; Sanders, D.; Benefield, P. The value of outdoor learning: Evidence from research in the UK and elsewhere. Sch. Sci. Rev. 2006, 87, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Recommendation 2006/962/EC on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM%3Ac11090 (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre, para la mejora de la calidad educativa. Boletín Oficial del Estado 295, 10 December 2013.

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Real Decreto 126/2014, de 28 de febrero, por el que se establece el currículo básico de la educación primaria. Boletín Oficial del Estado 52, 1 March 2014.

- Ion, G.; Cano, E. University’s teachers training towards assessment by competences. Educ. XX1 2019, 15, 249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Benejam, P. Los objetivos de las salidas. Iber Didáctica Cienc. Soc. Geogr. Hist. 2003, 36, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, M. Las salidas de campo como instrumento de aprendizaje. Dialéctica Libert. 2009, 2, 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Hernánz, S. Propuesta metodológica para el diseño de itinerarios didácticos de ciencias de la naturaleza. Didácticas Específicas 2016, 14, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Hernández, C. Las Ideas Previas del Concepto ‘Industria’ en el Alumnado de Geografía de 3º de la ESO. Las Salidas de Campo Locales Como Recurso Didáctico Para el Cambio y la Consolidación Conceptuales; Servicio de Publicaciones y Estadística de la CARM: Murcia, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- García López, A.M.; Foronda-Robles, C. De la teoría a la práctica educativa: Las salidas de campo, instrumento de aproximación a la realidad profesional. Aplicación en el máster en dirección y planificación del turismo. In Nuevas Enseñas de Grado en la Escuela Universitaria de Estudios Empresariales de la Universidad de Sevilla; Jiménez-Caballero, J.L., Rodríguez Díaz, A., Eds.; GEU Ed.: Granada, Spain, 2010; pp. 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Íñiguez Berrozpe, L.; Íñiguez Berrozpe, T.; Melero Polo, I. Un análisis de las salidas de campo autogestionadas con el Grado en Turismo tras tres años de experiencia. CLIO Hist. Hist. Teach. 2017, 43, 242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tulla, A. Los nuevos planes de estudio de los títulos de grado en geografía adaptados al modelo del espacio Europeo de educación superior (EEES). Estud. Geográficos 2010, LXXXI, 319–338. [Google Scholar]

- Pagés, J.; Santisteban, A. Una mirada del pasado al futuro en la didáctica de las ciencias sociales. In Una Mirada al Pasado y un Proyecto de Futuro. Investigación e Innovación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales; Pagés, J., Santisteban, A., Eds.; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2014; pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Garello, M.V.; Rinaudo, M.C. Autorregulación del aprendizaje, feedback y transferencia de conocimiento. Investigación de diseño con estudiantes universitarios. REDIE 2013, 15, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

| Objective | Procedure | |

|---|---|---|

| a. | To orientate geographically and to use cartographic and geolocation tools. | Urban itinerary between different significant public squares. |

| b. | To develop techniques for critical and systematic observation of territorial space. | Identification of urban structures and dynamics of the study area. |

| c. | To acquire social interaction skills as a source of knowledge of territorial dynamics. | |

| d. | To recognise the structures and dynamics of a geographical space. | |

| e. | To understand the process of tourist gentrification, in its diagnosis, causes and effects. | Cartographic representation of urban structures and dynamics activity and the final sharing activity. |

| f. | To reflect on the consequences of the intensification of the tourist use of urban centres. | |

| g. | To design cartographic elements of spatial representation. | Cartographic representation of urban structures and dynamics activity. |

| h. | To value the importance of field work as a teaching resource. | Full activity. |

| i. | To know basic procedures of urban geographic analysis. | |

| j. | To find out urban realities outside students’ surroundings. |

| PART A: Urban Geography Analysis | |

| 1. Mention two central areas with great socioeconomic dynamism today. | (Answer) |

| 2. What is the main characterisation of the urban structure of these areas? | O Presence of shops, restaurants and bars O Large open spaces O Distance from subway |

| 3. What is the main consequence of the intense social and economic dynamics of these areas? | O Price increase O Residents expulsion O The previous two answers are true |

| 4. Did you find the observation of the environment and drawing the map helpful to you to carry out this analysis of urban geography? | O Yes O No O Other: |

| 5. Have you had to interact with pedestrians to solve the exercise? Answer Yes or No and, if so, briefly explain if it was satisfactory. | (Answer) |

| 6. What difficulties have you encountered when performing this practical activity of geographical analysis? | (Answer) |

| 7. Have you learned new skills and geographic content? | (Answer) |

| 8. Do you think it is an interesting activity to apply in the educational field? | (Answer) |

| PART B: Conclusions (Contributions of the Activity) [Evaluate from 1 (Poor/Bad) to 5 (Good)] | |

| 1. Personal experience: | (Answer) |

| 2. Cultural learning: | (Answer) |

| 3. Social skills: | (Answer) |

| 4. Living with different people: | (Answer) |

| 5. Managing schedules: | (Answer) |

| 6. Urban mobility: | (Answer) |

| 7. Knowledge of another urban reality: | (Answer) |

| Others: | (Answer) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Hernández, C.; Yubero, C. Explaining Urban Sustainability to Teachers in Training through a Geographical Analysis of Tourism Gentrification in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010067

Martínez-Hernández C, Yubero C. Explaining Urban Sustainability to Teachers in Training through a Geographical Analysis of Tourism Gentrification in Europe. Sustainability. 2020; 12(1):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010067

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Hernández, Carlos, and Claudia Yubero. 2020. "Explaining Urban Sustainability to Teachers in Training through a Geographical Analysis of Tourism Gentrification in Europe" Sustainability 12, no. 1: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010067

APA StyleMartínez-Hernández, C., & Yubero, C. (2020). Explaining Urban Sustainability to Teachers in Training through a Geographical Analysis of Tourism Gentrification in Europe. Sustainability, 12(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010067