The Antecedents of Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions at Sporting Events: The Case of South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Information about Gwangju City and the Fédération Internationale de Natation (FINA) World Masters Championships Gwangju 2019

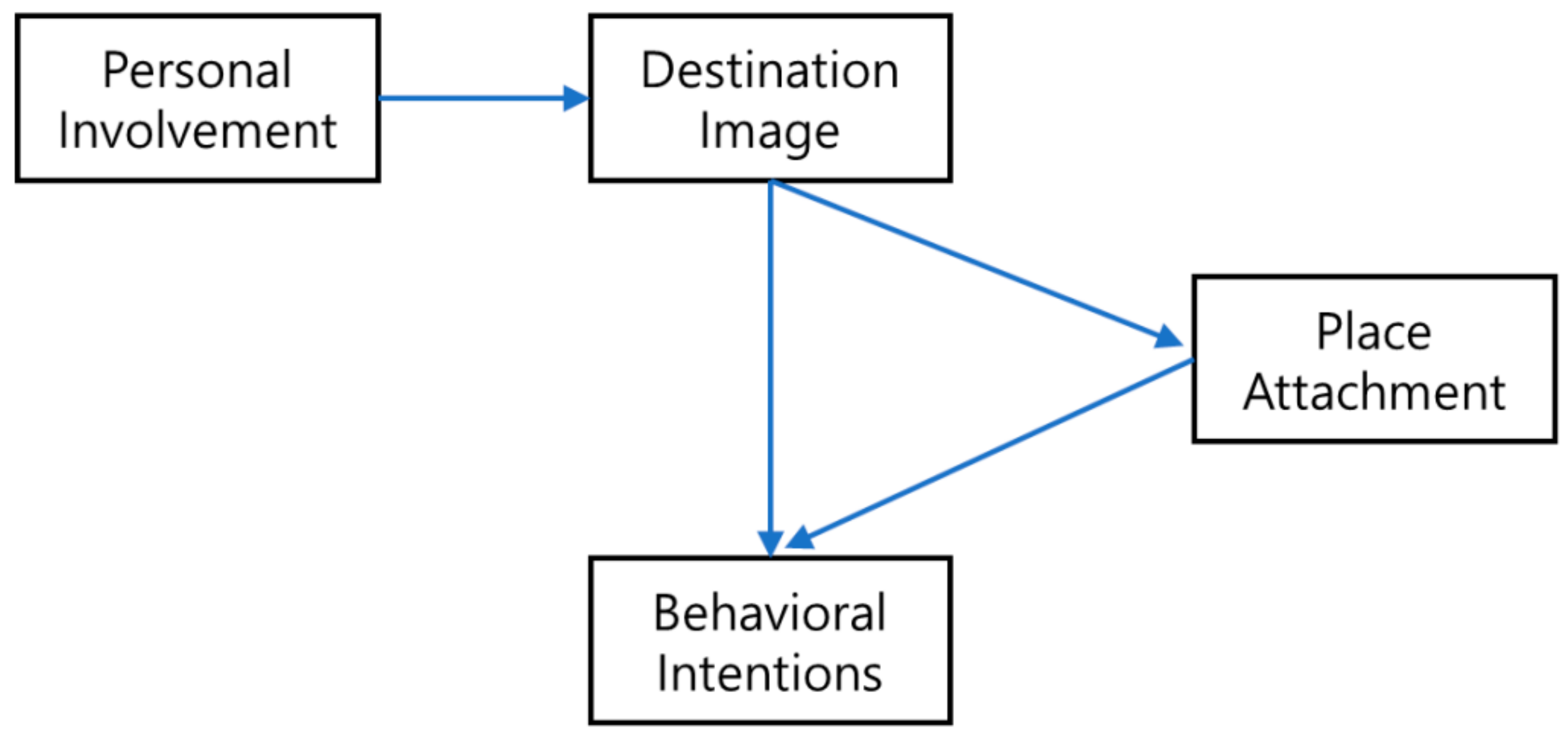

2.2. Personal Involvement

2.3. Destination Image

2.4. Place Attachment

2.5. Behavioral Intentions

2.6. Mediating Effect of Place Attachment between Destination Image and Behavioral Intentions

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Validity and Reliability

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.Y.; Hsu, M.K. The relationships of destination image, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: An integrated model. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.K.; Yu, J.G. Determinants of Behavioral Intentions in the Context of Sport Tourism with the Aim of Sustaining Sporting Destinations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assael, H. Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action; Kent Pub.: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.K. The key antecedent and consequences of destination image in a mega sporting event. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Cai, L.A.; Lu, L. Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, D.; Kaplanidou, K.; Apostolopoulou, A. Destination image components and word-of-mouth intentions in urban tourism: A multigroup approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Muskat, B.; Del Chiappa, G. Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.J.; Qi, C.X.; Zhang, J.J. Destination image and intent to visit China and the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. J. Sport Manag. 2008, 22, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, M. Mega-Events and Modernity; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fourie, J.; Santana-Gallego, M. The impact of mega-sport events on tourist arrivals. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1364–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chan, T.L.; Pratt, S. Destination Image of Taiwan from the perspective of Hong Kong residents: Revisiting structural relationships between destination image attributes and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2018, 19, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Lee, H.; Lee, S. Event quality, perceived value, destination image, and behavioral intention of sports events: The case of the IAAF World Championship, Daegu, 2011. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Santana, A.; Moreno-Gil, S. Perceived Sustainable Destination Image: Implications for Marketing Strategies in Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S. Exploring a suitable model of destination image: The case of a small-scale recurring sporting event. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 1287–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Uysal, M.; Brown, K. Relationship between destination image and behavioral intentions of tourists to consume cultural attractions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2011, 20, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; Qu, H. Destination image and behavior intention of travelers to Thailand: The moderating effect of perceived risk. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2103, 30, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; Van Der Veen, R.; Huang, S.; Deesilatham, S. Mediating effects of place attachment and satisfaction on the relationship between tourists’ emotions and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwangju City Hall. 2018 Annual Report of Gwangju City Hall. Available online: https://www.gwangju.go.kr/BD_0801080100/boardList.do?menuId=gwangju0508020100 (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Eun, W. Creating a human rights city through human rights governance—Taking the city of Gwangju as a model. Demo. Hum. Right 2009, 9, 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.C. The implicit influence of the May 18 Gwangju democratic movement on university student in Gwangju. Demo. Hum. Right 2016, 16, 75–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. May 18th Gwangju democratization archives collection development strategy for advancement of human rights awareness and democracy. Korean Soc. Arch. Stud. 2016, 48, 5–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, J.A. A study on “Light of Gwangju” seen in the cultural meaning of the light—Focused on the analysis of cultural events of the light. Korean Sci. Art Forum 2014, 17, 339–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.H. Analysis of 2008 and 2016 Gwangju biennale’s community-based projects and their significance. Korean Soc. Art Theory Pract. 2017, 23, 38–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.J.; Kim, I.S.; Yoon, G.W.; Lee, B.K. The creation plan for sport tourism attraction to promoting of urban tourism—For Gwang-ju metropolitan city. Korean J. Sports Sociol. 2010, 23, 131–153. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.M. An analysis of regional inhabitant’s expectation on opening 2019 world swimming championship. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2014, 23, 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- The FINA World Masters Championships Gwangju 2019. Information. Available online: https://www.fina-gwangju2019.com/contentsView.do?pageId=eng17 (accessed on 11 September 2019).

- Kang, P.J. The FINA World Masters Championships Gwangju 2019 Begins. OSEN. 12 July 2019. Available online: http://osen.mt.co.kr/article/G1111184100 (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Choi, C.Y. FINA World Masters Championships Gwangju 2019 Emphasizes Substance Ahead of Appearance. NewsMaker. 10 October 2019. Available online: http://www.newsmaker.or.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=79627 (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Collins, M.F. Sport for All in Government in the United Kingdom. In Sport, The Third Millennium, International Symposium; Landry, F., Landry, M., Yerled, M., Eds.; Press de I’Universiade Laval: Sainte-Foy, France, 1991; pp. 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, D.R. How an event on foreign soilis setting the trend for the future of big event sponsorship. Sport Mark. Q. 1993, 2, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Paddison, R. City Marketing, Image Reconstruction and Urban Regeneration. Urban Stud. 1993, 30, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowen, J.C.; Minor, M. Consumer Behavior, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Gavcar, E. International leisure tourists’ involvement profile. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 906–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.J.; Brown, G. An empirical structural model of tourists and places: Progressing involvement and place attachment into tourism. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, G.; Kapferer, J.N. Measuring consumer involvement profiles. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Mills, J.E. Destination image: A meta-analysis of 2000–2007 research. Jour. Hos. Market. Manage. 2010, 19, 575–609. [Google Scholar]

- Dichter, E. What’s in an image. J. Consum. Mark. 1985, 2, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridgen, J.D. Use of cognitive maps to determine perceived tourism regions. Leis. Sci. 1987, 9, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocquer, G.; Zins, M. Marketing do Turismo; Instituto Piaget: Lima Duarte, Brazil; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, C.A. Vacationscape: Designing Tourist Regions, 2nd ed.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.B. The measurement of destination image: An empirical assessment. J. Travel Res. 1993, 31, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, K.J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Pictorial element of destination in image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 537–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Lee, Y.K.; Lee, B. Korea’s destination image formed by the 2002 World Cup. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Njite, D. Relationship between destination image and tourists’ future behavior: Observations from Jeju island, Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Belhassen, Y.; Shani, A. Destination image, on-site experience and behavioural intentions: Path analytic validation of a marketing model on domestic tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1653–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K.S. Tourism destination image modification process: Marketing implications. Tour. Manag. 1991, 12, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chi, C.G.; Liu, Y. Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.S.; Lin, C.H.; Morais, D.B. Antecedents of attachment to a cultural tourism destination: The case of Hakka and non-Hakka Taiwanese visitors to Pei-Pu, Taiwan. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.T. Memorable tourist experiences and place attachment when consuming local food. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P. Towards a developmental theory of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Jordan, J.S.; Funk, D.; Ridinger, L.L. Recurring sport events and destination image perceptions: Impact on active sport tourist behavioral intentions and place attachment. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Busser, J.; Yang, J. Exploring the dimensional relationships among image formation agents, destination image, and place attachment from the perspectives of pop star fans. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 730–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, F.; Hongliang, Q.; Xuefei, W. Tourist destination image, place attachment and tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior: A case of Zhejiang tourist resorts. Tour. Trib. Lvyou Xuekan 2014, 29, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.S.; Ko, Y.J.; Connaughton, D.P.; Lee, J.H. A mediating role of destination image in the relationship between event quality, perceived value, and behavioral intention. J. Sport Tour. 2013, 18, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C. The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonge, J.; Ryan, M.M.; Moore, S.A.; Beckley, L.E. The effect of place attachment on pro-environment behavioral intentions of visitors to coastal natural area tourist destinations. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.M.; Kim, K.S.; Yim, B.H. The mediating effect of place attachment on the relationship between golf tourism destination image and revisit intention. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.J. Examining the relationships between destination image, place attachment, and destination loyalty in the context of night markets. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 11, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, K.Y. A Symposium on How to Attract 10 Million Tourists to Gwangju was Held. JoongAng Ilbo. 6 December 2018. Available online: https://news.joins.com/article/23187268 (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Lee, S.I. The effect of local tourist restaurant selection attributes on perceived value, customer satisfaction and revisit intention—Focused on Gwangju area. J. Hosp. Res. 2019, 18, 331–350. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplanidou, K. Relationships among behavioral intentions, cognitive event and destination images among different geographic regions of Olympic Games spectators. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Experimental Designs Using ANOVA; Duxbury Press: Belmont, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.K.; Mallawaarachchi, I.; Alvarado, L.A. Analysis of small sample size studies using nonparametric bootstrap test with pooled resampling method. Stat. Med. 2017, 36, 2187–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.F. The Relationships among Destination Image, Perceived Quality, Emotional Place Attachment, Tourist Satisfaction, and Post-visiting Behavior Intentions. Mark. Rev. Xing Xiao Ping Lun 2015, 12, 455–479. [Google Scholar]

- Kani, Y.; Aziz, Y.A.; Sambasivan, M.; Bojei, J. Antecedents and outcomes of destination image of Malaysia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 32, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T.; Feng, S. Authenticity: The link between destination image and place attachment. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; Jin, W.; Okumus, F. Constructing a model of exhibition attachment: Motivation, attachment, and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowall, S. International tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: Bangkok, Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 15, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.A.; Sparks, B. Predicting wine tourism intention: Destination image and self-congruity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale Items | Standardize Loadings | CR | AVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Involvement | ||||

| I derive pleasure by participating in the various attractions here | 0.919 | 0.909 | 0.720 | 0.885 |

| Being on holiday here is a bit like giving a gift to one self | 0.913 | |||

| I attach great importance to being on holiday in Gwangju | 0.619 | |||

| I have a lot of interest in Gwangju as a holiday destination | 0.717 | |||

| Cognitive Image | ||||

| The people in Gwangju are friendly and interesting | 0.714 | 0.891 | 0.672 | 0.861 |

| Gwangju offers suitable accommodation options | 0.753 | |||

| I am not worried about personal safety in Gwangju | 0.834 | |||

| The structure of the stadium is well built | 0.833 | |||

| Affective Image | ||||

| Gwangju is a relaxing place | 0.763 | 0.851 | 0.656 | 0.832 |

| Gwangju is an arousing place | 0.844 | |||

| Gwangju is an exciting place | 0.813 | |||

| Place Identity | ||||

| Holidaying in Gwangju means a lot to me | 0.827 | 0.898 | 0.746 | 0.872 |

| Gwangju is a very special destination for me | 0.833 | |||

| I identify strongly with Gwangju as a holiday destination | 0.840 | |||

| Place Dependence | ||||

| Gwangju is the best option for what I like to do on holidays | 0.708 | 0.886 | 0.723 | 0.866 |

| I would not substitute Gwangju for any other place for the types of things that I do during my holidays | 0.855 | |||

| I got more satisfaction out of holidaying in Gwangju than from visiting other similar places | 0.931 | |||

| Behavioral Intentions | ||||

| I will recommend Gwangju to other people to visit | 0.914 | 0.937 | 0.831 | 0.938 |

| I will say positive things about Gwangju to other people | 0.909 | |||

| I will visit Gwangju again in the next 12 months | 0.920 | |||

| Hypothesis | Path | Standardized Coefficient | t-Value | Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Personal involvement → Destination image | 1.035 | 9.883 *** | Yes |

| 2 | Destination image → Place attachment | 0.932 | 8.927 *** | Yes |

| 3 | Destination image → Behavioral intentions | 0.242 | 1.788 | No |

| 4 | Place attachment → Behavioral intentions | 0.529 | 3.861 *** | Yes |

| Path | Standardized Coefficient | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) (Bias-Corrected) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destination image → Place attachment → Behavioral intentions | Direct effect | 0.242 | 0.036~0.515 | 0.055 |

| Indirect effect | 0.493 | 0.257~0.677 | 0.007 | |

| Total effect | 0.736 | 0.679~0.787 | 0.003 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, Y.; Yu, A.; Kim, S.-K. The Antecedents of Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions at Sporting Events: The Case of South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010333

Jeong Y, Yu A, Kim S-K. The Antecedents of Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions at Sporting Events: The Case of South Korea. Sustainability. 2020; 12(1):333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010333

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Yunduk, Andrew Yu, and Suk-Kyu Kim. 2020. "The Antecedents of Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions at Sporting Events: The Case of South Korea" Sustainability 12, no. 1: 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010333

APA StyleJeong, Y., Yu, A., & Kim, S.-K. (2020). The Antecedents of Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions at Sporting Events: The Case of South Korea. Sustainability, 12(1), 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010333