1. Introduction

One of the main areas, currently underlined in the relevant literature, which is a specific form of open innovation theory, is the cooperation with users in the area of creating new or improved products. The idea of innovation coming from the user is currently widely discussed in the subject literature in the context of the lead user’s paradigm. The lead user was in the scope of interest of von Hippel, already at the end of the 1980s, who formulated the terms: “active customer paradigm” or “lead user”. He developed a new concept of innovation, arguing that users are just as important or even more important than producers, and the sources of innovation should be found in modern societies [

1]. Today, the main structural elements of this new lead user innovation paradigm are explained and highlighted by a collective effort that combines the development of theory with a large and rapidly growing collection of empirical evidence within different contexts.

At present, broad knowledge is being used as part of the extended network, which specifically covers the users’ competences [

2]. Due to focusing on the product functions most preferred by the customer, the duration and costs of the product development process as part of R&D (Research and Development), through cooperation with the user, can be reduced. It is common knowledge that research and development activity is expensive, and many investments in this area often do not bring the expected benefits. In particular, for small and medium-sized enterprises, high risk and financial investments are the main obstacles to the development of R&D activity [

3].

The importance of the user-driven innovation (UDI) concept in shaping innovative processes is of interest to researchers around the world. The issue of formulating recommendations, in the area of activating the R&D sector in enterprises using the UDI concept, is not fully recognized and despite its importance in the theory and practice of management, there is a lack of research and publications with a similar scope to that which is presented in the paper. Therefore, the authors identified a research gap (in the methodological, empirical and application areas), resulting from the lack of work containing the study of conditions for the cooperation with users within the UDI concept in the R&D activities of enterprises.

This is important because users are increasingly consciously influencing not only the final effect of created services and products, but also have a significant impact on the process of creating innovation. The standard in the modern world is slowly becoming a lack of acceptance for the activities of enterprises, which cause pressure on the natural environment, or introduce innovations that are implemented in conditions of disregard for social norms (e.g., arduous working conditions, child labor).

Considering above, the main purpose of this study is to present the empirical evidence in finding the determinants for the usage of the “user-driven innovation” concept (UDI). The work focuses on using this concept in R&D departments which are very often responsible for introducing this kind of innovation in a firm’s practice.

In this paper, the first part discusses the origin and the idea of the concept of user-driven innovation (UDI) in the context of “open innovation”. The second part discusses the determinants of UDI usage in R&D activity. The third part discusses methodological aspects related to measuring UDI determinants in enterprises. An attempt was also made to design empirical research in the area of using UDI in R&D activities of enterprises. The fourth part discusses the research results concerning the implementation of UDI in R&D departments of the surveyed enterprises in Poland in 2015–2017. Finally, based on the case study method, the process of UDI implementation in research and development activity in enterprises operating in Poland was discussed.

The designed and conducted empirical research, based on the authors’ original questionnaire created for this purpose in enterprises in Poland, allowed for drawing many interesting conclusions related to the determinants of using the UDI concept in the R&D processes of enterprises.

The added value of the analysis presented in the paper are the study of the relationships between any internal factors affecting the application of the UDI concept in the R&D sphere in Polish firms. The knowledge about these relationships is important for enterprises from other countries in which this concept is also at the initial level.

2. Literature Review

Taking into consideration the background of the theory, in the beginning of the 1990s, the publication of works by Nonaka and Takeuchi [

4] had taken place and the concept of “knowledge-based economy” [

5] began to develop. On its basis, the concept of “creative economy” [

6,

7] and the innovative system, together with the phenomenon of “networking” [

8] had developed, which consequently, in the first years of the 21st century, led to the formulation of the concept of “open innovation” proposed by Chesbrough in 2005. The open innovation model emphasizes the importance of ideas obtained by the company from the environment and the transfer of part of the innovation process to the outside. This means that the company can develop an idea drawn from the environment. It may also reject the proposed solutions, especially if their initial verification does not provide sufficient guarantees for success. Still, in order to maintain a competitive advantage, the focus should be more on meeting the needs of users, not only those clearly identified in market research, but rather on the hidden needs of users that can be revealed through alternative analytical methods, as well as by users themselves [

9].

“User-driven innovation” is one of the concepts of creating innovation developed in the beginning of the 21st century, next to the “open innovation” concept proposed by Chesbrough [

10]. UDI is based on a demand-driven approach to creating innovation. It is a process of using, by enterprises, the knowledge of users (both final consumers as well as enterprises and institutions) and obtaining financial benefits from it. When it comes to users’ knowledge, it is mainly about tacit knowledge acquired as a result of experience, which is very difficult to record and transfer. In the demand approach to creating innovation, it is important to discover the hidden needs of consumers. They can express their ideas and design solutions, and thus be a source of innovation. The innovations that are based on users’ knowledge meet the specific, personal needs of the users, which were not previously met by products that are available on the market [

11]. In some cases, potential users may be “more stable innovators” [

12] because they are aware of specific aspects in which a standardized commercial product does not meet their needs, and, in addition, information about the needs of these users is immaterial and “sticky”, which makes it difficult for producers to obtain information thereon. This idea of sticky information had already been analyzed by von Hippel [

13]. Furthermore, producers who, despite having received some information about the needs of users in some way, often cannot satisfy them, as heterogeneity is necessary, which often cannot be satisfied by this standardization and mass-produced solutions [

14]. Moreover, it should be emphasized here that the UDI-based innovation process should be based on understanding the real needs of users, and therefore it is the most difficult to define. Hence the need to use many research tools (e.g., methods based on ethnography) that enable the discovery of these unspoken, hidden needs of users, which, in turn, can be translated into the definition of new development areas for companies. Traditional marketing methods are not sufficient in this respect. You should actually get to know the user, his experiences and desires. Marketing research is more superficial. What should be additionally emphasized is that the innovation process should take place in a planned manner, and therefore, the use of users’ knowledge should not be sporadic (ad hoc) activity. Using hidden knowledge of users should be done by including them directly in R&D works. Hence, it is important to formulate an innovation strategy that includes actions in the field of UDI use.

Starting from 2005, when the UDI concept began to take shape, no single, universally binding definition of UDI was developed. This is due to the fact that there are many ways to engage with users and the empirical section of the article does not focus on that. However, few selected UDI definitions appearing in the literature on the subject are presented in

Table 1.

It is therefore a process, which incorporates users’ knowledge to develop the concept of new products or their improvement, based on the true understanding of users’ needs and their systematic involvement in the process of enterprise development. Interactions with users are simpler due to the development of information and communication technologies. Moreover, enterprise areas focused on designing new or improved solutions have evolved from a user-focused approach (as a potential customer) to user participation in the project (user as a partner). This is particularly evident in the case of business to business (B2B) relationships, where enterprises are users of a given product. According to Sanders and Stappers, engaging users in research and development at an early stage in the design process can create positive, long-term consequences [

17].

Organizations and enterprises are therefore looking for new methods to engage users in the R&D process. User-oriented research methods such as social computing, contextual design [

18], user-focused design and participatory design [

19], or empathic and emotional design [

20] and other usability methods already exist, but do not provide enough users to co-create in an open programming environment. In addition, there is a positive impact of user community involvement in the development of new products as part of R&D (New Product Development [

21]), precisely through methods based on the involvement of users in the research and development process, such as mass cooperation projects, discussed above as crowdsourcing, or so-called “wisdom of the crowds” (Wisdom of Crowds [

22]) in the collective creation of new content and applications. UDI has different levels and areas of user involvement, but all of them require their direct participation in the process of creating innovative products. Certainly, creating innovation in one of these ways requires a full understanding of the strategic, operational and intercultural implications, and the plan and willingness to deal with them.

3. Determinants of the Usage of the UDI Concept in Enterprises

The use of the UDI concept is interdisciplinary. In marketing literature, for example, methods have been developed to identify users’ needs. Entrepreneurship literature emphasizes the legitimacy of testing a concept of a product or a service at an early stage and business models, while literature related to project management indicates the aesthetic and functional role of design in creating products and services meeting the user’s needs [

23]. This interdisciplinary approach has undoubtedly many advantages and disadvantages. One of the main disadvantages is that different streams of knowledge significantly prevent a clear picture and process of using the experience, knowledge and needs of the user under the UDI concept [

24]. As it had been stated by B. Tacer, the literature on the subject shows that UDI can be related to: experience (of the user) with a given product or a service, satisfaction as a result of use (derivative) [

24], possibilities of future use [

25] or recommendations to other potential users [

26]. To get a clearer picture of the role of UDI in the business management process, you need to examine which aspects of UDI affect the use of your knowledge and experience [

23]. Some of them are exogenous determinants, such as the institutional framework, the structure of the sector, the technological knowledge available in a given area or the political and legal conditions in which the company competes. Other factors, such as shaped relationships with users, marketing orientation, building brand awareness by the company or decisions taken by companies regarding which protection measures are used are clearly endogenous.

The division of UDI usage conditions into the external and, depending on the internal potential of the enterprise, is also clearly visible. While an enterprise can (and often has) influence on shaping the internal potential in the field of R&D activation in various areas, the impact on external conditions is negligible.

Generally presented determinants have a multidirectional impact, which is why selecting key conditions is an extremely difficult and complex issue. Among many different conditions discussed in the literature on the subject, endogenous conditions such as: the need to build relationships with the user, marketing orientation of the enterprise, and building brand awareness (branding) might be the key determinants of the use of the UDI concept in research and development activities [

27].

To sum up, many factors related to the dynamics of innovation based on the UDI concept are still not fully understood and recognized. The purpose of this study is, therefore, to approximate some of these factors on the basis of empirical analysis, which may suggest the possibility of further research on the involvement of users in research and development processes. Authors have formulated the main hypothesis which is: UDI concept usage in R&D activity is determined by several endogenous factors whose individual attributes influence these actions in a multidirectional way.

3.1. Interaction with Users

The company’s focus on interaction with users is often associated with business performance, which is confirmed by the results of research conducted around the world [

28,

29,

30]. In turn, research results provide evidence that in the company’s environment, the orientation on interaction with users affects operational and exploration capabilities, which may contribute to the speed of product development and its innovation [

24]. The possibilities of using users’ knowledge can additionally affect the company’s financial results. The research of Hoops and Bücker shows a significant impact of interaction with users on the success and business efficiency of the company [

31]. The company’s focus on the user’s interaction therefore reflects the extent to which the company enables users of its products to contact the organization in order to influence R&D and cooperation. In this way, the user can indicate the need for individual business from the enterprise and its R&D activities. The theory of multiple perspectives of Pantaleo and Wicklund expands on this research [

32]. Enterprises aware of the importance of interacting with users know that using their knowledge can increase the advantage of new products for organizations (especially with regard to New Product Development (NPD)) [

33] and enable them to create innovation and ideas. Considering the above, the H1 research hypothesis has been formulated, assuming that the relationship between enterprises and users has an impact on R&D activity.

As the UDI concept developed, research attention has shifted to the role of users at various stages of the innovation process [

27,

34] A more dynamic approach has emerged, which indicates that activities related to user innovation not only differ between sectors, but also within the sector, and are additionally time-dependent [

15]. User activity increases after some of them have discovered a number of new opportunities to participate in creating innovation in the R&D process of their preferred brand or company [

35]. New solutions ultimately lead to an increase in demand for new projects on the part of R&D departments of enterprises, and thus, an increase in the potential and activity of the area of cooperation between producers and users. There are many ways to interact with users, and innovative areas developed with their engagement have been the subject of research in many sectors, such as: oil processing [

36], medical equipment [

37,

38], scientific instruments [

39], library information systems [

40], sport equipment [

41,

42,

43] or open-source software [

44].

3.2. Marketing Orientation of the Company

Marketing orientation [

45] is a business model that focuses on providing products designed according to the wishes, needs and requirements of customers. Unlike previous traditional marketing strategies that focus on creating points of sale for existing products, marketing orientation works the other way around, trying to tailor products to customers’ needs. Marketing orientation also includes monitoring competitors’ activities and their impact on customer preferences, as well as analyzing the impact of other exogenous factors [

46]. The term ‘marketing orientation’ first appeared in the early 1970s. Harvard University professor, Theodore Levitt, and other researchers said that the sales orientation model had been poorly constructed to provide products tailored to customers’ needs. Instead of producing products for the sole purpose of generating profits, they persuaded companies to change their strategy to develop products based on the desires, insights and opinions of customers. By using this customer intelligence, companies could produce products that supported their overall business strategy, successfully compete in an increasingly global and competitive market and provide solutions for current and future customer needs [

47]. A characteristic feature of marketing orientation is solving market problems, thanks to the use of new techniques and technologies enabling the creation of innovative products. This orientation requires close connection to research and development activities and marketing research [

31]. Research and development projects are based on the opportunities arising from technological development, as well as the impact of market factors. Research workers, designers and company management can be a source of new products and processes. However, the knowledge acquired from users (thanks to questionnaires, research, and discussion groups), competitors (thanks to market observation), suppliers and consultants is important. In the initial phase, the market requirements form the basis for determining the goals of the newly created enterprise or venture and for carefully developing the concept of doing business. This list of requirements created for the needs of R&D projects is based on determining the expectations of users, the state of competitiveness and market development, as well as defining technological, economic, time and organizational goals that can be treated as marketing goals. Parallel to the work on R&D projects, market preparations are being carried out. When new or improved products or processes enter the market, it will be seen whether the marketing concepts that underpin the research and development process have been realistically formulated or not. Focusing on users in research and development activities includes a constant inflow and processing of information about the acceptance or not of a new solution offered on the market (its choice is by the customer and satisfaction of the end user) [

15]. This requires the use of marketing tools at every stage of the innovation process [

31]. According to Li and Bernoff, the level of user involvement relevant to UDI is influenced by the use of social mechanisms and the possibility of effective communication with them [

33]. In the context of UDI, this involves the need to build an enterprise strategy striving to build relationships with users (personal and institutional). Research conducted abroad suggests that marketing opportunities, innovations, and their interaction have a positive relationship with both innovation performance and user-related activities [

31,

48,

49], so it is important that the marketing orientation be driven by UDI. Marketing orientation allows the company to use marketing tools and techniques effectively, as reported by Weerawarden and O’Cass [

50]. The ability to contact users and motivate them to participate in the innovation process is a prerequisite for successful UDI, as defined by Lettl [

51]. Although users are not always motivated to introduce innovations and often have cognitive limitations [

27], which can be a barrier to providing valuable information about their needs and experiences, it seems that enterprises with marketing orientation are more likely to use UDI in R&D processes. Considering the above, the H2 research hypothesis has been formulated, assuming that the specific marketing strategy assumptions of the enterprises are positively correlated with the propensity to use UDI in R&D processes.

3.3. Building Brand Awareness

Branding and labeling have an ancient history. Numerous scientific studies have proven the existence of branding, packaging and labeling strategies in ancient times [

52]. Abbing, in his book, described a new way of thinking about innovation and its practices, fueled by a unique look at branding which can be a driving force for innovation in products and services, giving them a certain vision of becoming accurate, authentic and original [

53]. The results of foreign studies provide evidence that brand orientation influences the company’s innovation [

54]. Innovations, in turn, help achieve better brand performance by systematically developing diverse values for users [

55]. The brand, therefore, has a bridging function between the internal strengths of the organization in the field of research and product development on the one hand, and the current or future values and preferences of users of these products on the other. Therefore, we are talking about branding of the future [

56], in which it is assumed to involve the recipient in the process of creating a brand. Considering above, the H3 research hypothesis has been formulated, assuming that the attributes of the company’s branding activity have a positive impact on UDI usage in the R&D sphere.

The issues of the innovative brand are raised in a signal way, including in the context of innovative brand experience, enabling the provision of unique functional and emotional elements to build strong relationships between the brand and the user [

57], or innovative brand communities whose members are a source of innovation and co-create brand value [

58]. In general, it might be said, that if a bond is established between the brand and the user, interest will turn into demand [

27]. In turn, the demand shows the desire to further participation in the innovation process. Finally, as a result of true cognition and intimacy, comes the knowledge about the true tacit needs of the users.

4. Identification of the Main Endogenous Determinants in Applying UDI in Enterprises

4.1. Description of the Research Sample

Research on the determinants for using the UDI concept in R&D was conducted in 2018–2019 in 57 enterprises in Poland, representing five sections of the economy (according to the PKD (Polish Classification of Activities’ Code)), which can be divided into two main groups—33 industrial enterprises (57.9%) and 24 service enterprises (42.1%). A necessary condition to participate in the study was the declaration on the availability of R&D facilities (a department, a unit), and on cooperation with users during research and development works. The analysis of the answers to the main questions regarding the characteristics of the phenomenon of using the UDI concept in R&D in the surveyed enterprises has provided many interesting results, which are presented in this chapter. It should be emphasized that these are the first studies conducted both in Poland and abroad, which focused on the use of the UDI concept in various sectors of the economy, and, more importantly, related to the linking of the use of the UDI concept with R&D processes of enterprises. The research was of quantitative and qualitative nature. In the case of the main part of the UDI concept usage characteristics, it was possible to verify test results enriched by in-depth statistical analysis. However, it was not possible to the same extent in all cases. Explanatory analyses, concerning the impact of variables, and exploratory ones characterizing the given phenomenon were carried out. Enterprises that use UDI were selected for the study on the basis of the age of the company and PKD codes. A full survey of 137 companies was planned, conducted by means of telephone interviews (57 companies participated). Therefore, the implementation rate (response rate) was 41.6%.

4.2. Adopted Research Assumptions

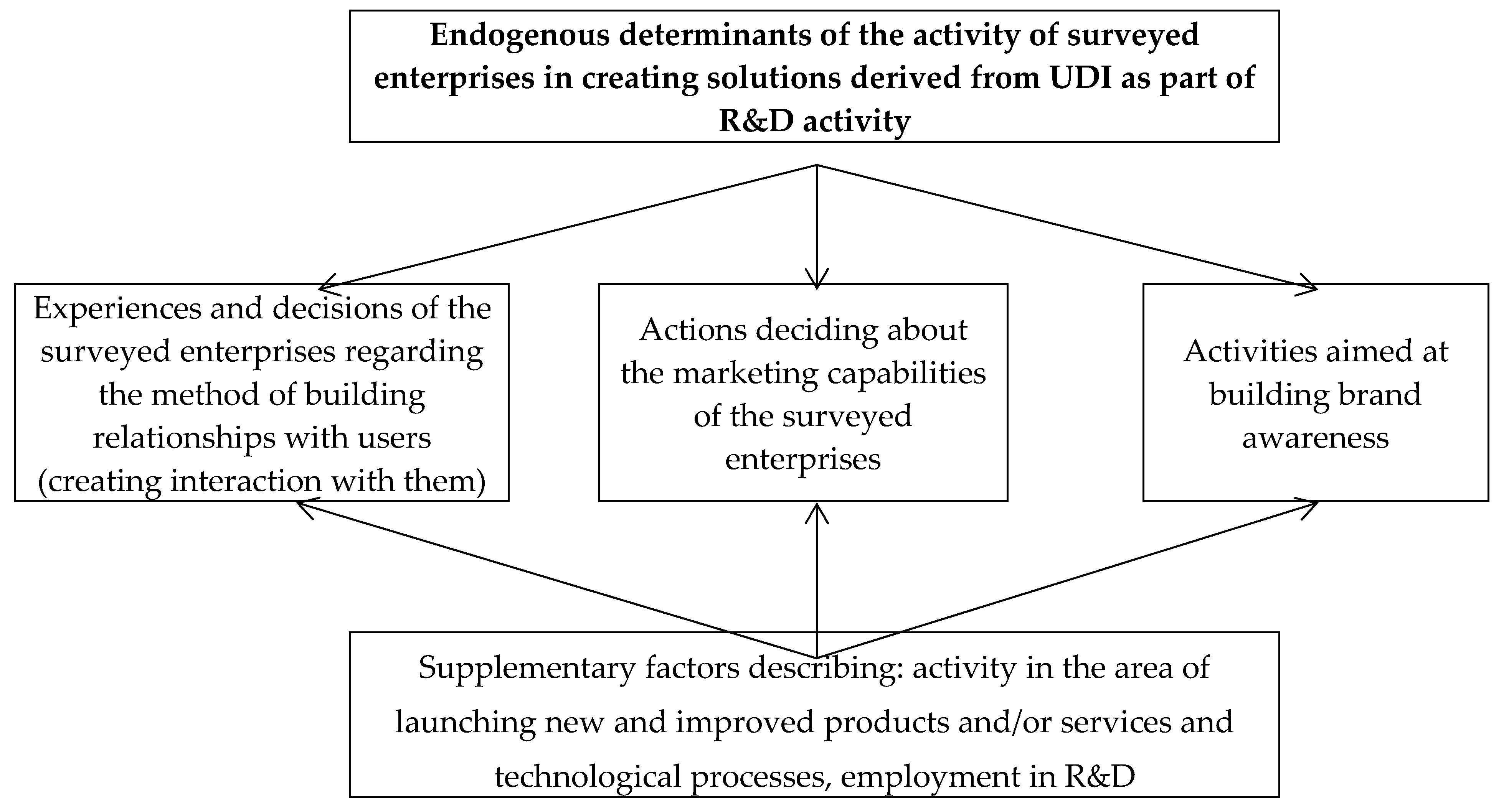

The theoretical considerations presented in the first part of the article are the basis for analyses presented in the work. According to these, it has been assumed that the use of the UDI concept in R&D in the enterprise will be influenced by various factors describing: the approach of the surveyed enterprises to building relationships with users, including creating interactions with them (group I of factors), activities determining the capabilities and marketing of surveyed companies (group II), and actions taken to build brand awareness in the minds of users (group III). All these factors can be classified as a group of internal conditions for the application of the UDI concept in an enterprise. It is also possible to consider the impact of the so-called external conditions for the implementation of the UDI concept in enterprises. This article, however, focuses on internal conditions.

In addition, factors of a more general nature were also taken into account describing, for example, activity in the field of launching new, improved products and/or services as well as technological processes, and the size of employment in R&D. In graphic terms, the adopted scheme for selecting factors for the study can be presented as follows (

Figure 1).

In detail, these factors can be presented as follows. The main dimension of the study is the percentage of solutions created as part of R&D activities originating from UDI (variable designated as UDI), where UDI1 means enterprises in which this percentage is 20% and less, UDI2 is 21–40% and UDI3 is 41% and more. In order to indicate which internal conditions may determine the use of solutions derived from UDI in R&D activities, the following groups of factors were considered.

Experiences and decisions of the surveyed enterprises regarding the method of building relationships with users (creating interaction with them) due to:

managers’ approach to perceiving the role of employees in creating value for users (A1),

activity of the surveyed enterprises in creating long-term relationships with users (A2),

frequency of measuring users’ satisfaction with products and services offered to them (A3),

approach to creating long-term relationships with users (abandoning formal forms of contact for informal contacts) (A4),

ways of information flow (enterprise–user and vice versa) (A5),

the level of integration of functional departments in the enterprise to meet the needs of users (A6),

including in the company’s strategy, activities aimed at creating value for users (A7),

regular contacts of the management of the surveyed companies with key users (A8), and

level of response to comments and requests from users (A9).

Actions deciding about the marketing capabilities of the surveyed enterprises, including respondents’ assessments regarding:

using communication tools with users of enterprise products and services (B1),

involvement in marketing activities (B2),

the amount of expenditure incurred on marketing activities (B3),

employment in the area of marketing (B4), and

linking marketing strategy with R&D (B5).

Activities aimed at building brand awareness, including respondents’ assessments regarding acceptance of:

perceiving the brand as the company’s main asset (C1),

activities aimed at building brand awareness (C2),

creating a positive brand image in the minds of users (C3), and

combining the brand concept with offered products and services (C4).

In each analyzed area, the ratings were presented on a 3-point scale, where 1 was the highest answer confirming the application of e.g., the indicated way of building relationships with users (these answers were marked as: A11, A21, A31 etc.), 2 was the difficult to answer, (marked as: A12, A22, A32 etc.), and 3 was the lowest answer indicating e.g., not using this method when building relationships with users (marked as: A13, A23, A33 etc.).

In addition, responses from representatives of enterprises participating in the study have been also taken into account describing:

- 4.

Activity in the area of launching new, improved products and/or services (NP), where NP1 means enterprises that have introduced such a product on the market and NP2 are those which have not introduced such a product.

- 5.

Activity in the field of launching new, improved technological processes (NT), where NT1 means enterprises that have introduced such a technological process and NT2 are those which have not introduced such a process.

- 6.

The volume of employment in R&D (BR), where BR1 means enterprises in which 10 people or less are employed in R&D, BR2 is 11–20 people, and BR3 is 21 people or more.

4.3. Description of Mathematical Methods Used in the Work

In the paper, to present the relationship between the selected variables, the correspondence analysis which constitutes one of the methods for statistical, multiple analysis was applied. The correspondence analysis is one of the methods for statistical, multiple analysis and it allows to recognize accurately the coexistence of the categories of variables (or objects) measured on a nominal scale. This method is suitable for small-scale tests and it is their main advantage. It allows to find the relationship between the variables which are surveyed on the different scale, so it provides to analyze the data measured on a different scale in the one type of analysis. This method helped specify, in detail, the issues of co-existence of the categories of variables (objects) measured on a nominal scale [

59,

60]. The procedure for this method involves the following several steps.

The starting point is dedicated to creating a complex which comprises the number of particular categories of variables adopted to specify

n objects. For this purpose, the Burt’s matrix is very often applied [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]. Firstly, it is required to create a complex matrix of

Z indicators which comprises blocks (submatrices) referring to consecutive variables:

Z = [

Z1, …,ZQ], where

Q means the number of characteristics. The components of the complex indicator matrix take only 0 and 1 values, depending on whether a particular object has the distinguished category of variable or not.

- 2.

Determining of the dimension of actual space of the coexistence.

In the next step, the dimension of actual space of the coexistence of answers to questions is determined under formula:

Taking into account the Greenacre’s criterion, the best size of projection of the categories of variables where eigenvalues meet the condition:, is selected.

At the same time, according to this assumed criterion for selecting the significant eigenvalues (), the results of the analysis of variables recorded in the form of Burt’s matrix can be improved taking into account the following formula [

61,

62]:

where

Q signifies number of variables, and

signifies

k-th eigenvalue.

- 3.

The graphic presentation of the results obtained.

In the next step, the results of the correspondence analysis are presented in graphic form. This is possible by indicating points depicting the categories of variables at a one-, two- or three-dimensional coordinate system. It is worth noting that it allows to lose only the small possible part of information on the actual structure of links between surveyed variables. If the space larger than three is the best form to present the coexistence of characteristics, then we need to select another method for presenting the results. For such a purpose, in the space of both smaller and larger sizes, the methods of classification can be applied [

66]. The categories of all analysed characteristics shall be defined as objects. At the same time, the values of projection coordinates of each category are considered as the variables. New values of coordinates are determined as follows:

where

is the matrix of modified values of coordinates for the category of examined variables with the

K ×

k dimension,

is the matrix of original values of coordinates for the category of examined variables with the

K ×

k dimension,

is the diagonal inverse matrix of specific values (

γk) with the

K ×

k dimension,

γk –

k is the specific value which is the square root of the k eigenvalue (

λk),

is the diagonal matrix of modified eigenvalues with the

K ×

k dimension, and K is the dimension of the genuine coexistence space.

5. Results

In

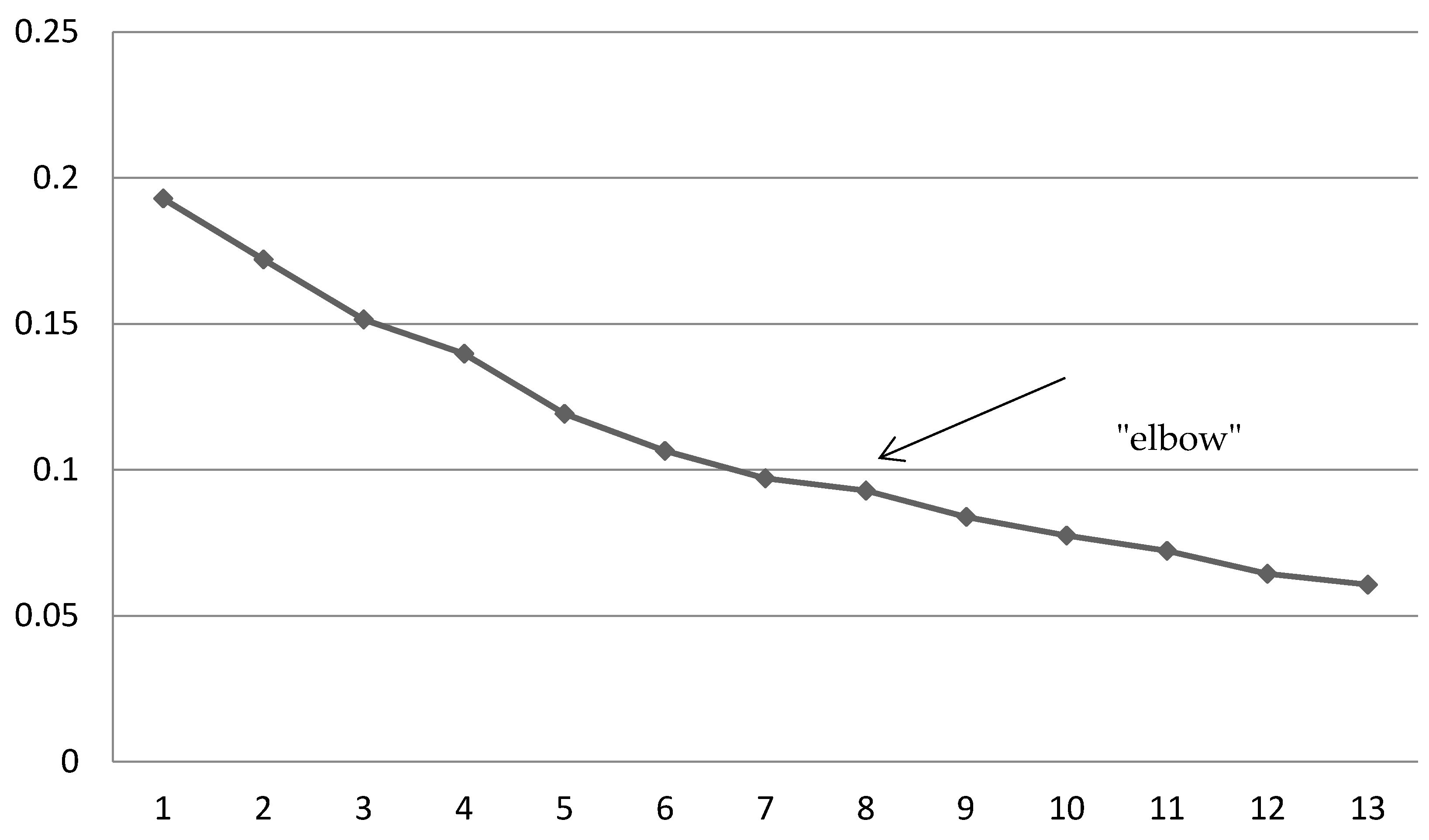

Table 2, the results of the analysis of correspondence is presented. Correspondence analysis was carried out on the basis of Burt’s matrix with dimensions of 49 × 49 formed from 17 variables. The dimension of the actual space of co-occurrence of answers to the analyzed questions is 32. Next, the extent to which eigenvalues with a lower dimension explain total inertia (λ = 1.8824) was checked. In accordance with the Greenacre’s criterion, the main inertias larger than

. were taken into account as important for the study.

Table 2 shows that these are inertia for

K with a value of, at most, 13 (see

Table 2). In addition, a graph of eigenvalues was prepared and using the “elbow” criterion, it was found that the space for presenting co-occurrence of variable variants should be eight-dimensional (

Figure 2).

In order to increase the quality of the mapping, the eigenvalues were modified according to Greenacre’s propositions, and the original and modified eigenvalues, along with the degree of explaining the total inertia, are presented in

Table 2.

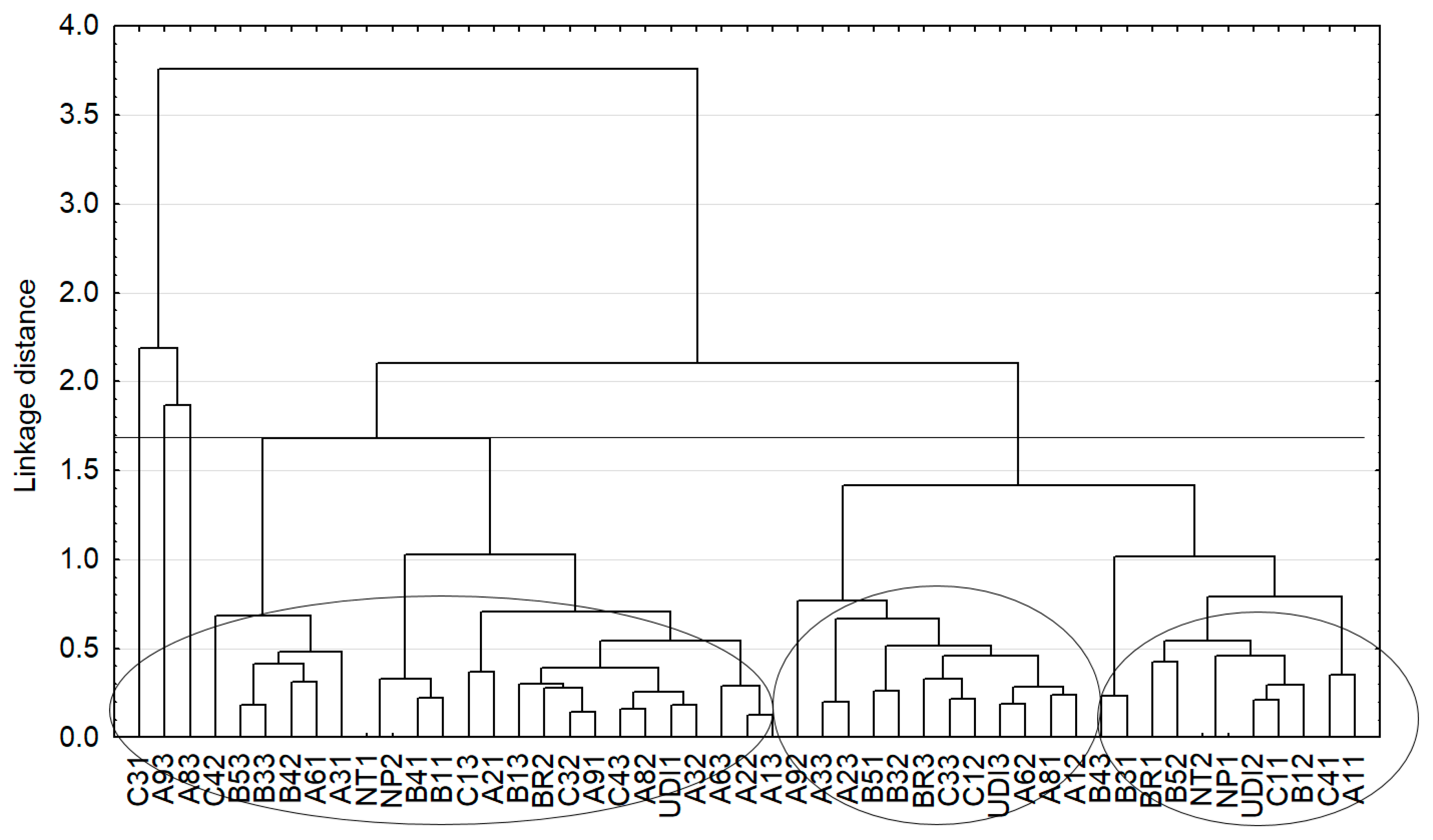

After modification, the first eight eigenvalues represented 77.60% of the modified total inertia. Due to the large number of analyzed variables and their variants, interpretation of results obtained in three-dimensional space was very difficult [

67]. Therefore, in order to better interpret the results, the Ward method was used, which made it possible to identify the relationships between the variable variants, and which is presented in

Figure 3. The determination of the critical distance value at which class interruption was made was determined by using a meter proposed by T. Grabiński [

63,

64]:

where

i = 2, 3, …, n = 1,

is the length of the

i-th tie (

i-th is the branch of the tree).

Critical value of distance determined by Grabiński’s method was 1.38.

As a result of the applied methods, five classes were created. Due to the lack of connections between the UDI variable and the categories of variables in classes 1 to 2, the detailed interpretation has been made only for classes from 3 to 5. This means that enterprises which use the UDI concept in their activities are not interested in the creating of a positive brand image in the minds of users (C31). This kind of factor is not as important in their business practice at the current level of implementing the UDI concept. The same situation can be observed in the case of the next factors as: regular contacts of the management of the surveyed companies with key users (A83), and level of response to comments and requests from users (A93). However, in this case, it should be noted that the same situation can be observed, both in enterprises in which the percentage of solutions created as part of R&D activities originating from UDI, is high and less. These kinds of factors were considered important by the surveyed enterprises, regardless of their level of interest in implementation of UDI concepts in their business practices.

Class I (C31),

Class II (A93, A83)

Class III (C42, B53, B33, B42, A61, A31, NT1, NP2, B41, B11, C13, A21, B13, BR2, C32, A91, C43, A82, UDI1, A32, A63, A22, A13): applies to enterprises in which the percentage of solutions created as part of R&D from UDI is the lowest (20% or less). These enterprises employ between 11 and 20 people in R&D. They introduced new, improved technological processes, but did not introduce new, improved products. The examined objects, due to various criteria, have very diverse experiences in how to build their relationships with users, such as:

their activity in creating long-term relationships with users is at least average, and the situation is similar, in terms of frequency, of measuring user satisfaction with products and services offered to them,

the level of integration of functional departments in the company to meet the needs of users is at the highest or weakest level, and

regularity of management’s contacts with key users is average, while the level of response to comments and requests from users is at the highest level.

Enterprises from this class, due to actions determining marketing abilities, can be assessed relatively negatively, because despite the employment level, at least at the average level, there is no link between marketing strategy and R&D in these enterprises, the amount of expenditure on marketing activity does not occur or is very low, and also, the use of communication tools with users of products and services is rated very good or very bad. Considering the activities aimed at building brand awareness, it should be noted that the surveyed companies do not perceive the brand as their main asset. Rather, they perceive creating a positive brand image in the minds of users at an average level and combine the concept of the brand with the offered products and services at an average level at most.

Class IV (A92, A33, A23, B51, B32, BR3, C33, C12, UDI3, A62, A81, A12) includes enterprises employing 21 people or more, with the highest percentage of solutions created as part of R&D activities derived from UDI (41% and more). They regularly contact key users, but do not have a firm opinion on: the perception of the role of employees in creating value for users, the level of integration of functional departments in the company to meet the needs of users, as well as the level of response to comments and requests from users. They assess the amount of expenditure on marketing activities as average. They believe that the links between marketing strategy and R&D activities are at the highest level. They very positively perceive the brand as the company’s main asset, while they negatively assess the creation of a positive brand image in the minds of users.

Class V (B43, B31, BR1, B52, NT2, NP1, UDI2, C11, B12, C41, A11) applies to enterprises employing up to 10 people, in which the percentage of solutions created as part of R&D activities originating from UDI is within 21–40%. These companies introduced new improved products to the market but did not introduce new improved technological processes. They positively assess the managers’ approach to perceiving the role of employees in creating value for users and the amount of expenditure incurred on marketing activities. They claim that the use of communication tools with users of products and services, as well as the linking of marketing strategy with R&D activities, are at their average level. They highly value the perception of the brand as the company’s main asset and combine the brand concept with the offered products and services.

The use of correspondence analysis allowed identifying relationships between variable variants and, as a result, draws the following synthesized conclusions:

The surveyed companies believe that introducing innovations based on user feedback is very important from the point of view of their research and development activities,

enterprises have very diverse experiences regarding how to build their relationships with users, marketing abilities and brand awareness, and

Most solutions from UDI concern enterprises employing at least 21 people.

6. Conclusions

The concept of user-driven innovation, although known in highly innovative countries, is not yet widespread in a country like Poland. This is indicated by the results of research, starting from the fact that enterprises do not have enough contact with their own products’ users while conducting R&D activity. This comes also in terms of formulating innovation strategy. Contact with users, even if they are frequent, are not due to the fact that the UDI concept is known in companies. Rather, it results from intuitive actions in the field of adapting to current market needs. These activities do not form a certain systemic whole because they are not part of the companies’ strategy. Although there are few publications based on empirical research regarding this particular topic, the literature on the subject of innovation management is still very poor in this respect, considering a country like Poland [

27]. The authors have tried to fill this knowledge gap by creating a foundation for further considerations into the use of the UDI concept in enterprises in Poland. There are no detailed guidelines or good practices that would facilitate the process of using UDI in R&D activity.

Research results show that enterprises, whose percentage of solutions are created by using the UDI concept, are aware of brand building in a strategic sense, but this does not translate into operational activity-branding at the level of contact with users. There is, therefore, no consistency in the activities carried out by enterprises. The use of UDI in enterprises is a relatively new phenomenon in Poland, but not a foreign one. There is interest among companies in this concept, which should be strengthened in the coming years.

Poland is a country with one of the lowest innovation rates. It is influenced by many factors, including the system environment [

68,

69,

70]. Western countries which are better developed economically, including in the area of innovation activity, especially the Scandinavian countries, noticed many years ago the need to activate activities aimed at a wider use of the UDI concept in the innovative activity of enterprises. For example, Denmark [

71] is the country where, in recent years, the greatest emphasis has been placed on user-driven innovation. Since the 1970s, Danish researchers working in the IT sphere had been focusing on improving the usability of software, giving users greater impact on the final product. Thanks to coordinated government efforts, many Danish small and medium-sized enterprises are also expected to increase their focus in exploiting user-driven innovation in the coming years. One reason is that the Danish government has initiated support activities to encourage companies to work with the UDI concept. Finland can also boast of great interest in the UDI concept. Initiatives based on user innovation in Finland are one of the main drivers of Finnish innovation, and its promoter is the TEKES agency, a publicly funded expert organization that finances research, development and innovation in Finland. It supports the use of the UDI concept at two levels: by supporting research in educational and research institutions, and by activating cooperation between educational and research institutions and Finnish enterprises. Additionally, in Norway, companies recognize that using UDI can lead to gaining valuable information from users at an early stage of the innovation process at the R&D stage. An example of the UDI activation is the program for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) sector called Innovation Norway. In turn, the Swedish business sector is actively promoting the UDI concept among giants such as ABB, Volvo, Electrolux, Ericsson and SK [

72]. A precursor example of the application of the concept is the cooperation between Electrolux and the companies involved in design research: Herbst, LaZar and Bell, who conducted ethnographic research supporting development work. In addition, the Swedish Industrial Design Foundation (SVID) actively participates in supporting user-driven innovation. To date, SVID has promoted initiatives that contribute to the spread of UDI in Sweden, such as the Product Innovation Program at the University of Karlstad [

73]. These examples of the most innovative countries of the European Union are the proof for a stable trend that emerges regarding the positive impact of the UDI concept on the broadly understood innovation process. In Poland, this concept is still considered new. There are not many scientific researches and publications on this topic. As for the innovation policy, there is still a lack of system support programs activating initiatives in the field of cooperation with users, which took place many years ago in the most innovative countries, examples of which were given earlier. Therefore, in terms of Poland’s innovation policy, the use of UDI in enterprises can be strengthened by adapting the following areas: promotion of the use of the UDI concept in R&D processes in the broadly understood entrepreneurial sector, and activation of the business environment sphere implemented by creating separate network organizations such as clusters able to promote the UDI concept. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the promotion of UDI among enterprises, entrepreneurs’ associations, local government officials, and business environment institutions implemented by national and local information campaigns. This is why the authors have made some recommendations regarding the promotion of activities related to the use of UDI in R&D processes. These links can be strengthened by adapting the following areas:

Preparation of the use of the UDI concept in R&D processes in the broadly understood entrepreneurial sector. Research and analysis of the current state of UDI use and the definition of tools to increase the scope of contact with users.

Activation of the business environment sphere. Creation of open innovation laboratories and development of good practices for using this concept.

Creating academic knowledge centers based on the use of UDI-cooperation between enterprises and business environment entities.

In the academic and scientific community. Promoting the UDI concept by creating educational programs on UDI, developed and supported through grants and subsidies.

The above recommendations and proposed directions of change, together with the effort placed in the promoting of the UDI concept among Polish enterprises, especially in the sphere of SMEs, will therefore have an immanent impact on many aspects of the research and development process, and consequently, the innovation process, and thus, equalization of competitive opportunities on the international market.

As for the cyclical closure, it should be emphasized that the main reflection that arises as a result of research in the field of determinants for the use of the UDI concept in the surveyed enterprises, is the fact that most of them are not aware that the implemented activities apply to UDI. All surveyed enterprises, which were a prerequisite for starting the study, cooperated to a greater or lesser extent with the users of their products. However, they are not aware that the activities undertaken in this area are in line with the concept of innovation created by users, described in the literature on innovation management. Most often they combine it with activities at the interface of marketing (contact with the user) and human resources management (skillful contact, effective cooperation and the use of knowledge coming from the user), aimed at building good and lasting relationships with users. According to the authors, the conscious implementation of the UDI concept in enterprises is a unique way to stimulate research work by acquiring the knowledge and information necessary in the R&D process from users and using it to design products or services that meet the current and future needs of the users. In addition, cooperation with the leading user gives the opportunity to predict the future, undiscovered needs of the mass user, and this fact can determine the sustainable development of the enterprise.

In this paper, endogenous determinants for the use of UDI in enterprises were analyzed. In the theoretical part of the article, three research hypotheses have been formulated regarding the influence of some internal factors. These are: relationships between enterprises and users, the way of preparing specific marketing strategy assumptions, and the attributes of the company’s branding activity which may influence the use of the UDI concept in R&D activities in the surveyed enterprises. The research results presented in the paper only partly confirmed the hypotheses. At the current stage of development of the surveyed enterprises representing various levels of development, despite the declared level of innovation, it is difficult to expect that all assumptions will be met. As highlighted in the description of the results obtained, the implementation of the UDI concept is influenced by many factors, not only those resulting from internal processes in companies.

Certainly, in the future, external conditions for the use of UDI in R&D should be analyzed. Therefore, there is a premise for further empirical research and scientific considerations in this particular field of innovation management. This would lead to formulate a model for using the UDI concept in enterprises.

This research has, of course, its limitations. Due to the fact that verification of the quality of the UDI determinants would require difficult and long-term research, there is a premise for further research in this regard, both in Polish and international conditions. After some time, it would be advisable to re-verify the results of research on the determinants of UDI use in enterprises to check for any deviations in this regard. Determinants of using the UDI concept are definitely an interesting research problem that requires further research and analysis. The research results presented in this work supplement the current knowledge in the field of internal conditions affecting the implementation of the UDI concept in enterprises starting to implement this concept.